3.1. Tree Recruitment in the Forest Stands

The values shown in

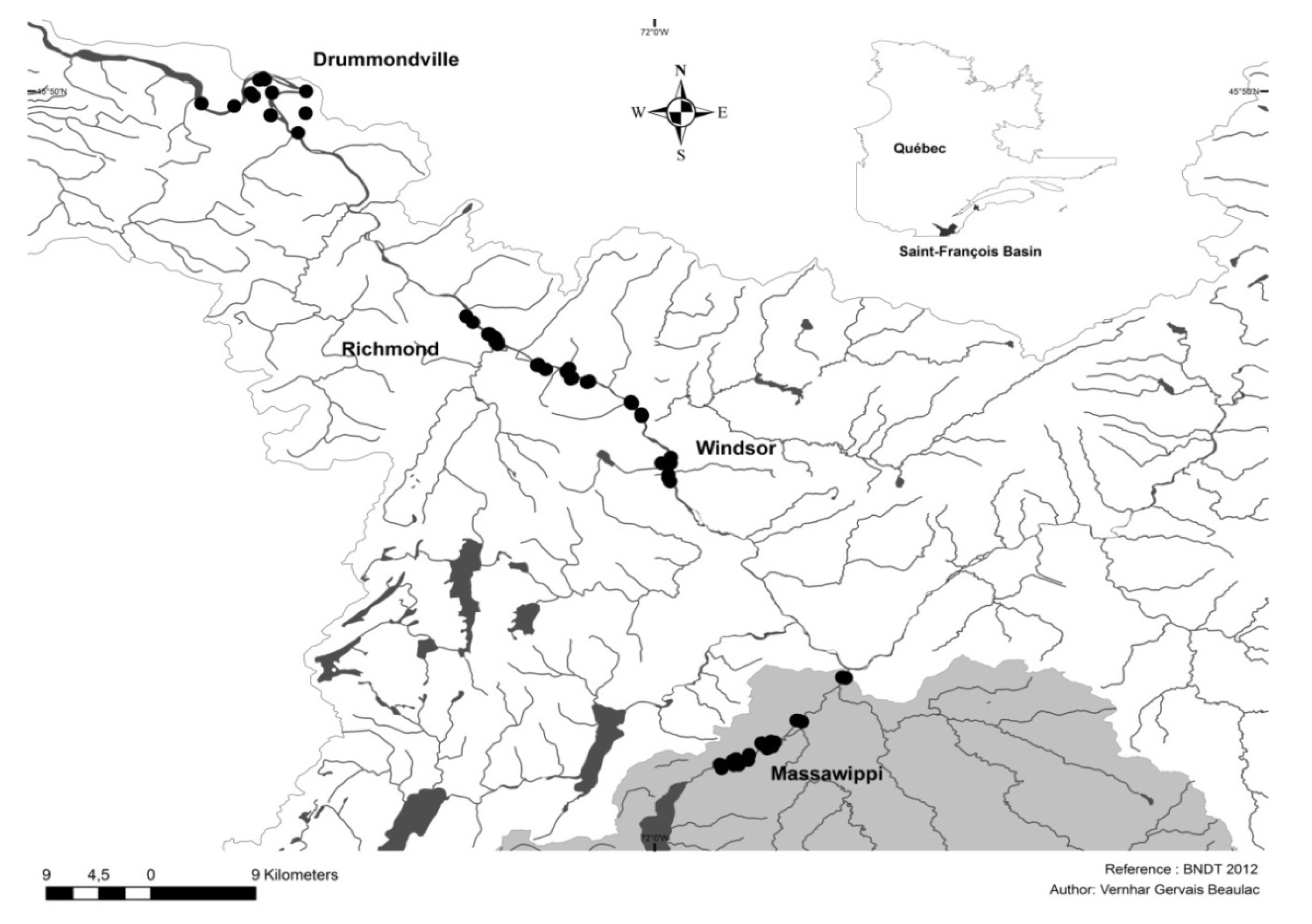

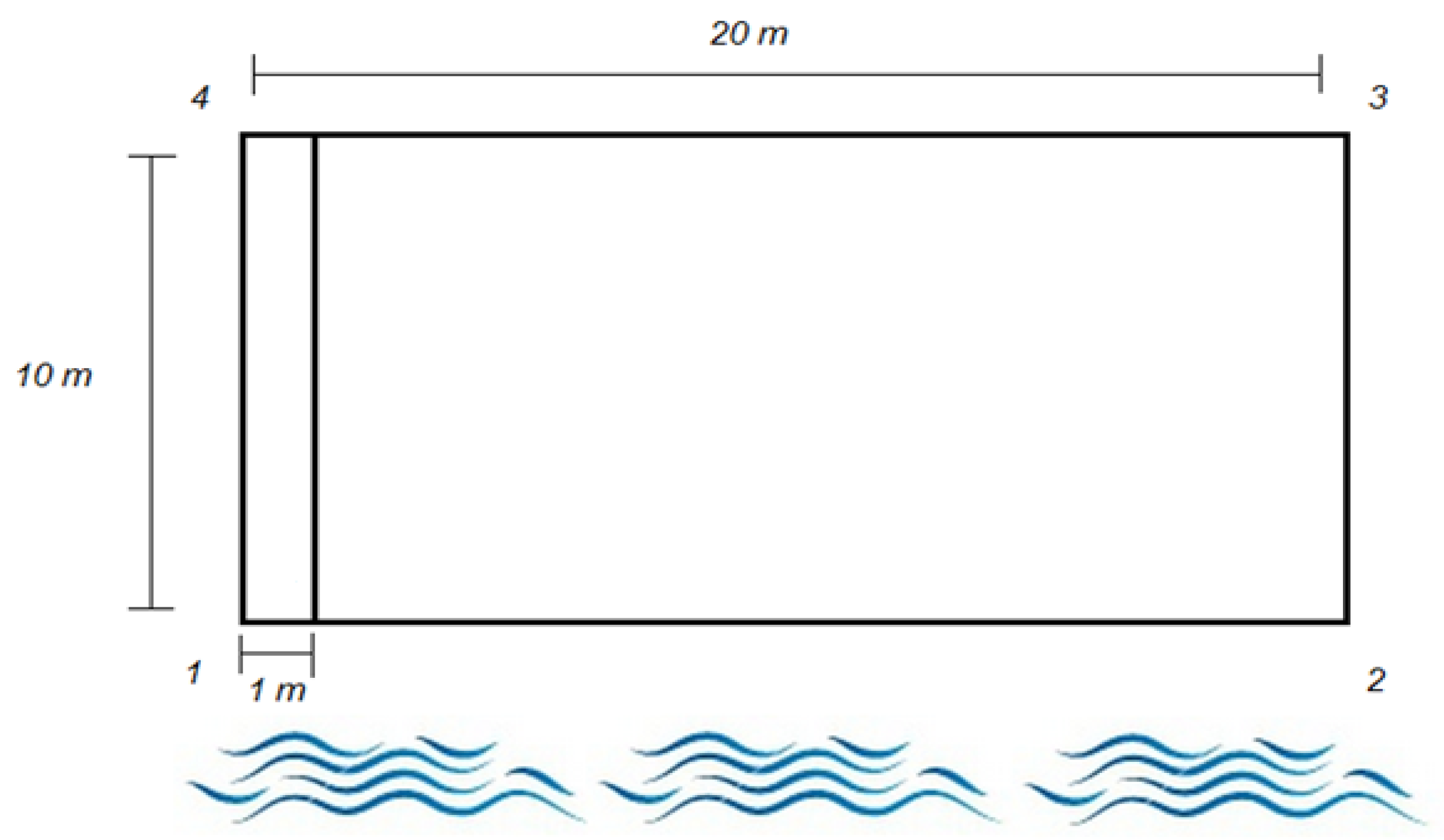

Table 4 provide the tree stem density indices (seedlings and saplings) based on the means, medians, quartiles and standard deviations. The upper part of the table contains all of the regeneration data from the quadrats (strip of 1 m × 10 m) for the Massawippi and Saint-François river sectors (

n = 720). By grouping the data based on the flood recurrence zones, it can be seen that regeneration is lower in the high-flood zone (FFz) than in the other two zones (MFz and NFz). Mean values of 1.41 and 1.20 are obtained for the 0–20-year zone (FFz) compared to 2.39 and 2.26 for the no-flood zone (NFz). For the seedlings in Category S1, the density indices are comparable with the total indices for all of the quadrats based on the different zones. Note that the establishment of seedlings (S1) in the high-flood zones (FFz) shows a lower index. This low recruitment rate could be explained by the higher flood frequency, which prevents annual shoots from being maintained and causes a drop in the survival rate of the young saplings in subsequent years. As floods can sometimes occur once or twice a year [

19], saplings have a smaller chance of survival. The saplings in fact are at risk of being rooted up and carried away by the current. The other phenomenon to consider is the inflow of sediment during floods, which could completely cover the year’s saplings. It is estimated that 15 to 35 mm of flood sediment could be deposited along flooded rivers in this area [

19,

34,

35]. It is also important to consider the presence of herbaceous species, such as ostrich fern (

Matteuccia struthiopteris) and stinging nettle (

Urtica dioica), which densely populate the alluvial plains (

Figure 2) in these areas and which can hinder the establishment of the young tree stems by shade and their very dense root system. Furthermore, some species, such as silver maple and ash, pioneer species that are able to better adapt to poorly-drained soils, can affect the growth of young tree stems by their canopy, particularly for shade-intolerant species. All of these phenomena combined—strong current, buried seedlings and interspecific competition—can affect the recruitment of the various tree species and their survival in active alluvial zones, in addition to altering the structure of the communities over the long term [

20,

36].

Table 4.

Stand density index of tree stems in different flood zones and no-flood zones.

Table 4.

Stand density index of tree stems in different flood zones and no-flood zones.

| Flood and no Flood Zones a | Min | Q1 | Median | Mean | Q3 | Max | SD |

|---|

| Total | | | | | | | |

| 0–20 years | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.85 | 1.41 ** | 1.65 | 10.10 | 1.87 |

| 20–100 years | 0.10 | 0.80 | 1.40 | 2.54 ** | 3.10 | 14.40 | 3.26 |

| No flood | 0.10 | 0.90 | 1.60 | 2.39 ** | 3.10 | 12.67 | 2.46 |

| S1 | | | | | | | |

| 0–20 years | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.65 | 1.20 ** | 1.40 | 10.10 | 1.81 |

| 20–100 years | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.40 | 2.35 ** | 3.05 | 13.40 | 3.10 |

| No flood | 0.10 | 0.70 | 1.60 | 2.26 ** | 3.10 | 12.67 | 2.48 |

| S2 | | | | | | | |

| 0–20 years | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 * | 0.18 | 0.80 | 0.19 |

| 20–100 years | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 * | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.14 |

| No flood | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 * | 0.10 | 0.70 | 0.16 |

| G1 * | | | | | | | |

| 0–20 years | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 * | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| 20–100 years | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 * | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| No flood | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 * | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| G2 * | | | | | | | |

| 0–20 years | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 * | 0.18 | 0.80 | 0.18 |

| 20–100 years | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 * | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.16 |

| No flood | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 * | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.15 |

For the other diameter categories (S2, G1 and G2), the density indices have relatively comparable values among the various zones (

Table 4). The results show that the density of stems from the three categories of saplings and seedlings is significantly lower than that obtained with the S1 saplings group. Lastly, with regard to the stands in the no-flood zones, the densities obtained in the categories (S2, G1 and G2) are relatively comparable to those obtained for the flood zones,

i.e., densities close to the maximum values of 0.70 to 0.10.

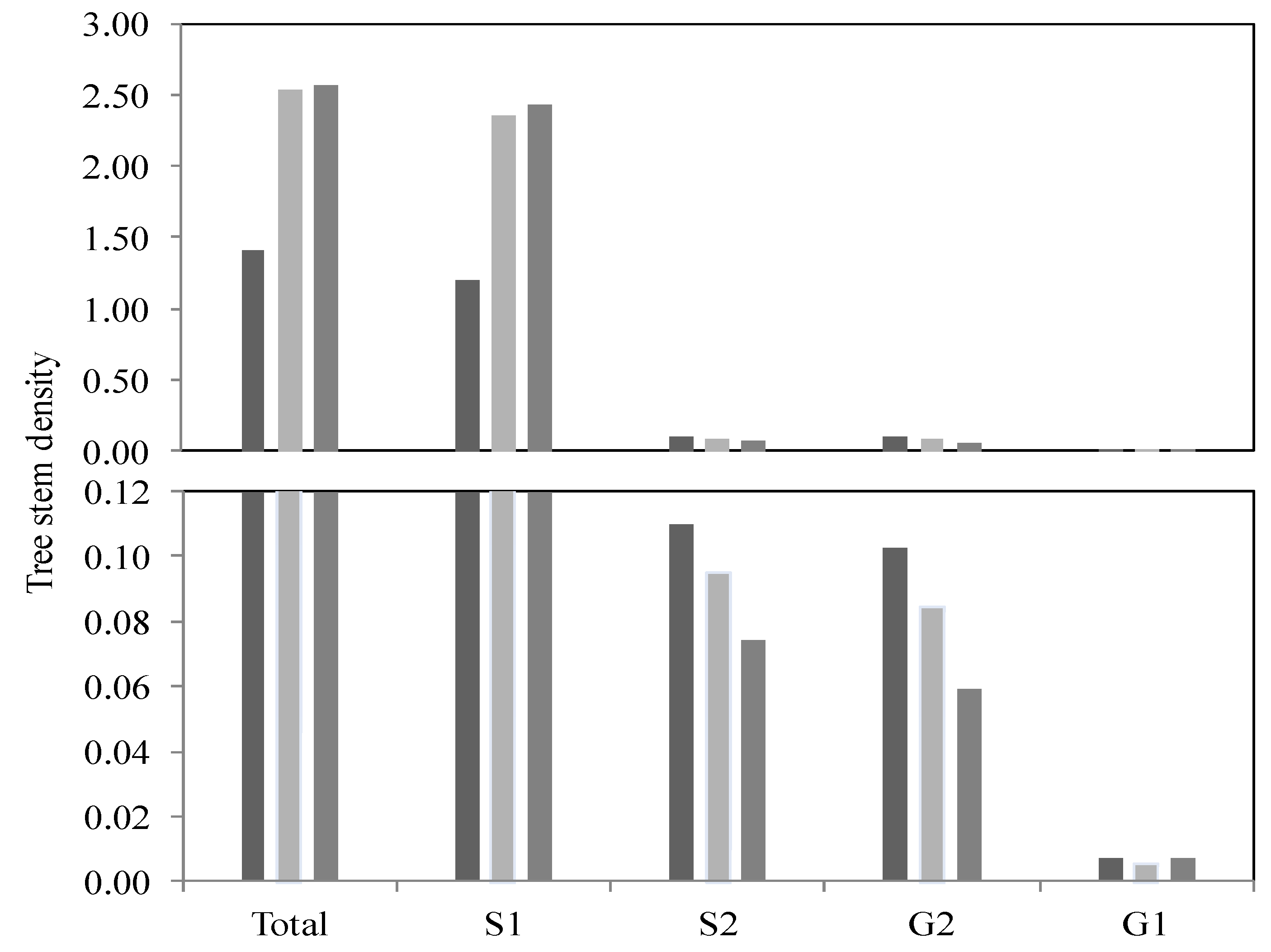

To validate the regeneration data, Student’s and Mann–Whitney tests were applied for the three study areas (FFz, MFz and NFz). The normality of the data was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and a logarithmic transformation was done to reach a normal data distribution, required for the use of the Student’s test. In the FFz zones, the resulting values reveal a significant difference in the regeneration of the tree stratum (S1) between the other two zones (MFz:

p = 0.098; NFz:

p = 0.000). A significant difference is also observed between the MFz zone (

p = 0.095) and the NFz zone (

p = 0.000) for the density of the saplings (S1), which shows greater regeneration for these two zones compared to the FFz zone (

Figure 6). The lower measured indices are associated with the high-flood zones (FFz). However, no significant value was obtained for the S2, G1 and G2 groups.

Figure 6.

Histogram depicting tree stem density (n = 720) based on the diameter category (S1, S2, G1 and G2 groups) and as a function of the different flood zone recurrences and outside of the floodplain zones. (dark color = interval of 0–20 years; gray color = interval of 20–100 years; pale grey color = outside the floodplains; sampling area: 1 m × 10 m).

Figure 6.

Histogram depicting tree stem density (n = 720) based on the diameter category (S1, S2, G1 and G2 groups) and as a function of the different flood zone recurrences and outside of the floodplain zones. (dark color = interval of 0–20 years; gray color = interval of 20–100 years; pale grey color = outside the floodplains; sampling area: 1 m × 10 m).

Regeneration is the result of several conditions, such as seed dispersal, germination and the establishment of young stems, survival success, edaphic conditions, and interspecific competition [

22,

23,

36]. Interspecific competition is likely an important factor in the successful establishment and maintenance of tree species in the zones outside the floodplains. The effect of competition among the species for resources (e.g., light, nutrients) and their survival rate are linked to endogenous factors, which, in fact, are common to all vegetation communities [

17,

22,

24]. These main factors generally impact the recruitment rate and likelihood of the survival of young tree stems [

15]. The trend observed for forest stands in Eastern North America is characterized by high sapling mortality during the first years of establishment and the stabilization of the surviving individuals in subsequent years [

12,

22,

36].

Finally, an important factor that appears to be more critical is the impact of successive floods (i.e., interval of 0–20 years), which seems to result in the low recruitment rate of the tree species. The velocity of the current and the sediment (1–3.5 cm in thickness) left behind following the flood recession very likely contribute to reducing the young saplings’ likelihood of survival and, over time, decreasing the regeneration potential of these riparian populations. This, coupled with other factors, such as interspecies competition (common in all tree stands), the establishment of non-indigenous species and all other anthropogenic disruptions, makes these riparian stands and their short- and medium-term development especially precarious.

3.2. Forest Stands Structure

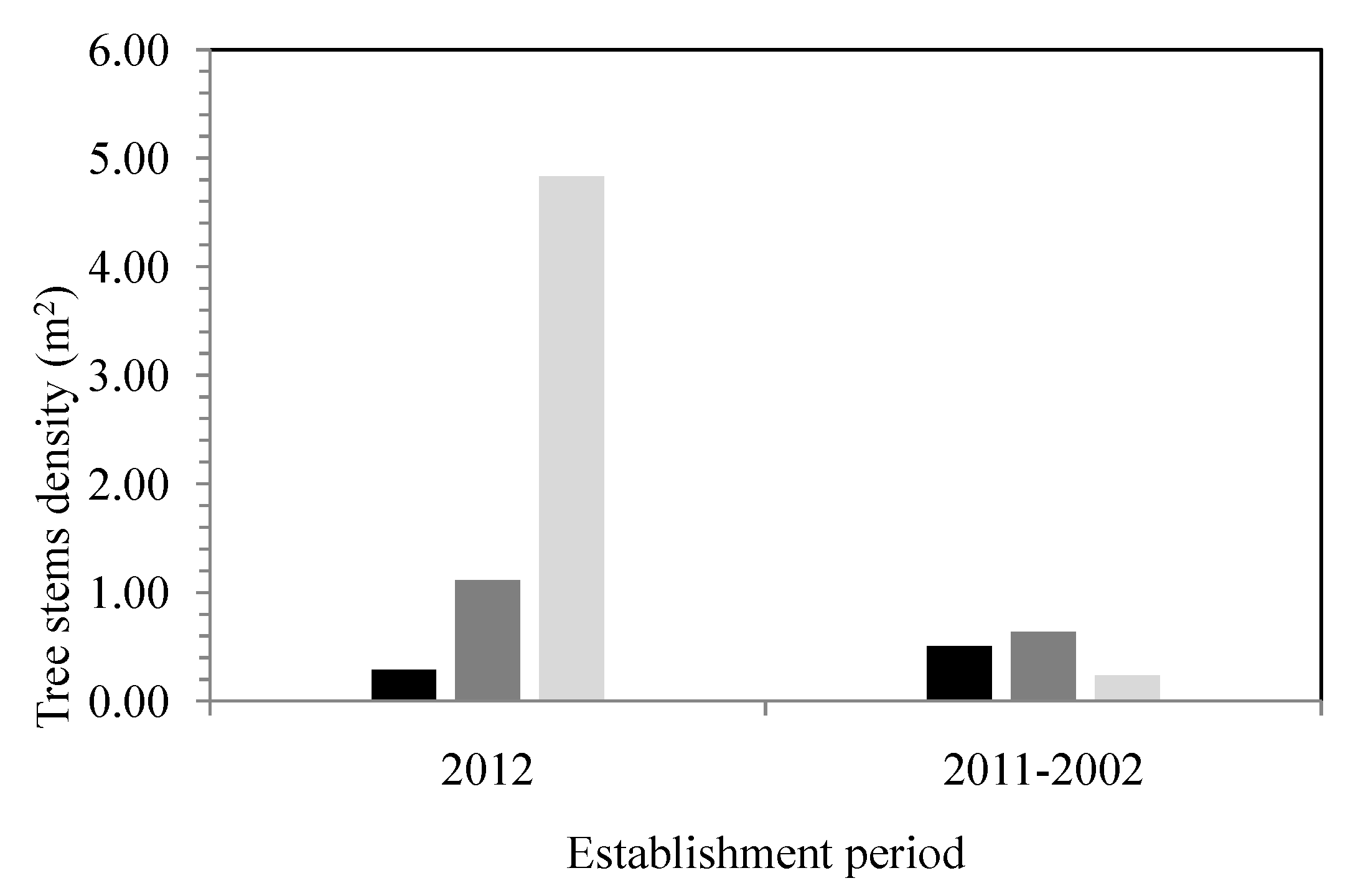

The data based on tree diameter and the dendrochronology analysis show that the stands are young in all of the zones, with a higher contingency of individuals found between 13 and 42 years (2001–1972) and 43–52 years of age (1971–1962) (

Figure 7). Despite the presence of a few old individuals, most of the tree specimens analyzed are found in the following age classes: 13–22 years (2001–1992) and 33–42 years (1981–1972). These forests are therefore mainly made up of young stands with a low rate of renewal, especially in high-frequency flood zones (

Figure 8). Furthermore, the age structure of the stands outside the floodplain zones (NFz) shows a higher number of young individuals

versus older trees. The number of trees drops as the age of the individuals increases. This pattern of distribution is the same as the one observed for the other two flood zones (FFz and MFz). The Mann–Whitney and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests that were applied to all of the data did not, however, show significant differences statistically between each zone, except for one site (

p = 0.029).

Several of the riparian stands that were analyzed were already established on the riverbanks in 1945 [

30], and they basically still occupy the same land area. In some locations (e.g., Richmond and Windsor areas), an extension of woodland was even noted along the banks of the Saint-François River corridor ([

30], pp. 64–66). In short, most of the wooded areas have remained in place since 1945, but younger individuals (e.g., 70–80 years) are found in the riparian stands. It is therefore estimated that a significant proportion of trees found in the frequent flood zones were established between 1962 and 1971, a period that coincides with a decrease in flood frequency in these areas [

19]. In fact, the period of 1956–1970 was characterized by a marked decrease in floods throughout the Saint-François River catchment. It is likely that this decrease in the number of floods over this period had the effect of favouring the chances of the survival of young saplings that were newly established and that now account for a major portion of the trees in the current riparian stands. Many tree species, such as red ash (

Fraxinus pennsylvanica) and black ash (

F. nigra), located in active floodplains, also have a diameter greater than 15 centimeters (

Figure 9), which would indicate an age from 20 and 30 years. However, further field work in the coming years will probably confirm these observations. Finally, there are marked differences in the composition of the tree species found in the flood zones (FFz and MFz) and those in the zones (NFz) outside the floodplains (

Table 5). Species, such as red ash (

Fraxinus pennsylvanica), black ash (

F. nigra), silver maple (

Acer saccharinum) and, occasionally, box elder (

Acer negundo), are the main species that form the riparian tree stands, whereas the outer zones are characterized by species commonly found in wood stands in the temperate zones of southern Québec (e.g.,

Acer saccharum,

Betula alleghaniensis,

Tsuga canadensis). Red ash is the dominant species in the flood zones, with 91 (FFz) and 25 (MFz) individuals surveyed, accounting for 40.3% and 25.9%, respectively, while red maple (

Acer rubrum) dominates the no-flood zones (NFz) with 107 (40.8%) individuals. The latter species is also well represented in the flood plains with 39 (17.3%) and 65 (28.0%) individuals surveyed.

Figure 7.

Histogram showing the distribution of the number of tree stems (n = 720) according to age group and as a function of the different flood zone recurrences and outside floodplain zones. (dark color = interval of 0–20 years; gray color = interval of 20–100 years; and pale grey color = outside the floodplains).

Figure 7.

Histogram showing the distribution of the number of tree stems (n = 720) according to age group and as a function of the different flood zone recurrences and outside floodplain zones. (dark color = interval of 0–20 years; gray color = interval of 20–100 years; and pale grey color = outside the floodplains).

Figure 8.

Histogram showing the density of tree stems (n = 720) according to the establishment period between 2012 and 2002 and as a function of the different flood zone recurrences and outside the floodplain zones. (dark color = interval of 0–20 years; gray color = interval of 20–100 years; and pale grey color = outside the floodplains).

Figure 8.

Histogram showing the density of tree stems (n = 720) according to the establishment period between 2012 and 2002 and as a function of the different flood zone recurrences and outside the floodplain zones. (dark color = interval of 0–20 years; gray color = interval of 20–100 years; and pale grey color = outside the floodplains).

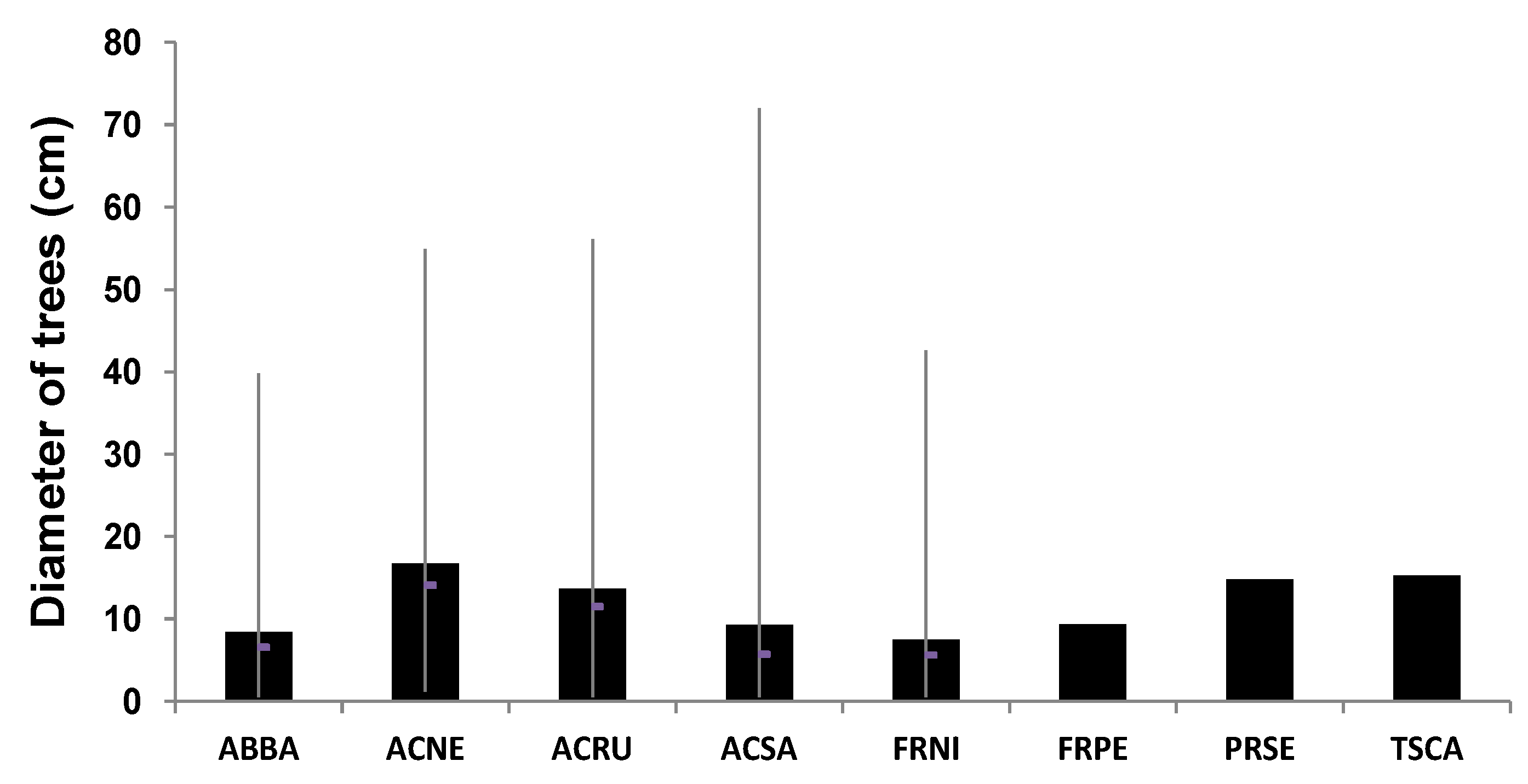

Figure 9.

Diameter of main riparian trees analyzed in the flood zones (FFz and MFz) and no flood zones (NFz). The data show the mean, maximum, minimum and median values.

Figure 9.

Diameter of main riparian trees analyzed in the flood zones (FFz and MFz) and no flood zones (NFz). The data show the mean, maximum, minimum and median values.

Notes: ABBA, Abies balsamea; ACNE, Acer negundo; ACRU, Acer rubrum; ACSA, Acer saccharinum; FRNI, Fraxinus nigra; FRPE, Fraxinus pennsylvanica; PRSE, Prunus serotina; TSCA, Tsuga canadensis.

Table 5.

Distribution, number and tree species in different zones (FFz, MFz and NFz).

Table 5.

Distribution, number and tree species in different zones (FFz, MFz and NFz).

| Tree species a/Number of tree stems | Flood interval 0–20 years | Flood interval 20–100 years | Outside floodplains | Total |

|---|

| Abies balsamea (L.) Miller | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 31 (11.8) | 32 (4.5) |

| Acer negundo L. | 14 (6.2) | 6 (2.6) | 0 | 20 (2.8) |

| Acer rubrum L. | 39 (17.3) | 65 (28.0) | 107 (40.8) | 211 (29.5) |

| Acer saccharinum L. | 17 (7.5) | 0 | 0 | 17 (2.4) |

| Betula alleghaniensis L. | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (1.5) | 8 (1.1) |

| Fagus grandifolia L. | 11 (4.9) | 3 (1.3) | 0 | 14 (1.9) |

| Fraxinus americana L. | 0 | 35 (15.1) | 1 (0.4) | 36 (5.0) |

| Fraxinus nigra Marsh. | 20 (8.8) | 20 (8.6) | 0 | 40 (5.6) |

| Fraxinus pennsylvanica Marsh. | 91 (40.3) | 60 (25.9) | 14 (5.3) | 165 (23.1) |

| Ostrya virginiana (Mill.) K. Koch. | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 12 (4.6) | 13 (1.8) |

| Pinus strobus L. | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) |

| Populus balsamifera L. | 0 | 2 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (0.3) |

| Populus grandidentata Mich. | 5 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 5 (2.2) |

| Populus tremuloides L. | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 5 (1.9) | 6 (0.8) |

| Prunus serotina L. | 4 (1.8) | 19 (8.2) | 20 (7.6) | 43 (6.0) |

| Quercus rubra L. | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) |

| Tilia americana L. | 5 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 5 (2.2) |

| Tsuga canadensis L. | 0 | 15 (6.5) | 49 (18.7) | 64 (8.9) |

| Ulmus rubra L. | 5 (2.2) | 2 (0.9) | 0 | 7 (0.9) |

The data in

Table 6 provide more detail on the diameter size-class frequency of the two main species (

Acer rubrum and

Fraxinus pennsylvanica) identified in the 94 quadrats. Of the 225 stems counted in all of the quadrats, red maple (

A. rubrum) was found to occur mainly outside the floodplains (NFz), though it also occurs in flood zones, but to a lesser extent. The mean diameters range from 12.6 to 16.9 cm, with a maximum value of 56.1 cm. There is a total number of 329 red ash trees (

F.

pennsylvanica), with individuals being especially represented in the high-flood zone (FFz). The mean diameters range from 4.0 to 10.1 cm, with a maximum value of 58.5 cm. Most of the trees are found in the 1–10 cm diameter size class, with a very limited number of old trees (e.g., 70 years). Most of the specimens analyzed make up these two species (

A. rubrum and

F. pennsylvanica), which are representative of young forest stands, with a few old individuals [

37].

Table 6.

Diameter of the two dominant tree species, size-class frequency in different flood zones (FFz and MFz) and no flood zones (NFz).

Table 6.

Diameter of the two dominant tree species, size-class frequency in different flood zones (FFz and MFz) and no flood zones (NFz).

| Tree species | Total tree stems a | Average diameter (cm) | Median diameter (cm) | Min–max diameter (cm) | Diameter size-class frequency |

|---|

| Acer rubrum | 225 | 13.6 | 11.5 | 0.5–56.1 | 1–10 | 10–20 | 20–30 | 30–40 |

| FFz (interval 0–20 years) | 28 | 16.9 | 15.5 | 1.7–39.0 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| MFz (interval 20–100 years) | 35 | 15.5 | 13.5 | 1.2–44.9 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 2 |

| NFz (Outside of the floodplains) | 161 | 12.6 | 11.0 | 0.5–56.1 | 74 | 52 | 31 | 3 |

| Fraxinus pennsylvanica | 329 | 9.3 | 5.2 | 0.2–58.4 | 1–10 | 10–20 | 20–30 | 30–40 |

| FFz (interval 0–20 y) | 271 | 10.1 | 5.9 | 0.2–58.4 | 174 | 51 | 28 | 13 |

| MFz (interval 20–100 y) | 35 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 0.4–52.9 | 20 | 1 | 1 | – |

| NFz (Outside floodplains) | 23 | 6.8 | 3.1 | 0.4–40.0 | 19 | 3 | 1 | – |

3.3. Edaphic Conditions of the Tree Stands

The

Appendix provides additional elements on edaphic conditions (e.g., drainage, soil pH, particle size, SOC (%), nitrogen, soil biomass) for the various areas under study (FFz, MFz and NFZ ) in the two study sectors (MAS and STF). In terms of soil pH, the FFz is characterized by slightly more acidity, but comparable to the MFz, whereas soil acidity is higher in the no-flood zones (NFz). In general, the soils outside the flood zones have the lowest pH values in both sectors (MAS and STF), which can probably be explained by the greater abundance of biomass in the soil. It is known that litter decomposition and humification releases acidifying products (e.g., fulvic and humic acids), which can increase soil acidity, especially in the surface horizons [

38]. The no-flood zones have significantly thicker litter, namely three to four times more than the frequent flood zones. The soils located outside the floodplains also have the highest concentrations of SOC (%),

i.e., close to twice the levels found in the other zones (FFz and MFz). From a textural standpoint, the soil in the FFz have textures with higher proportions of silt, which is characterized by loam, silty loam or loamy sand matrices. In the no-flood zones, the soil particle sizes (%) are comparable with the FFz, but the proportion of sand is generally coarser, and in some places, the soil profile contains gravel or pebbles. However, the slightly coarser textures do not seem to affect the regeneration of the annual saplings, which is greater in the NFz zones.

With respect to edaphic conditions, the most marked differences among the three zones mainly pertain to textural variations (e.g., coarser sand and presence of gravel), soil pH levels, soil organic carbon and nitrogen concentrations, along with the variable thickness of the litter, which are significantly greater in the no-flood zones. The presence of a fair amount of litter in fact modifies the soil properties by helping increase organic carbon and nitrogen levels, especially on the soil surface, which, in turn, helps release acidifying products associated with the breakdown of organic matter and its mineralization and humification [

38], thus increasing soil pH. Lastly, the presence of thick ground litter observed in the NFz zones definitely favours seed germination, whereas in the areas where there is no litter, as can be observed in several frequent flood zones, germination is more compromised. Soils with high organic carbon and nitrogen concentrations also likely promote the establishment of new stems and their maintenance in the tree stratum [

16,

17].