Using Biokinetic Modeling and Dielectric Monitoring to Assess Anaerobic Digestion of Meat-Processing Sludge Pretreated with Microwave Irradiation and Magnetic Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

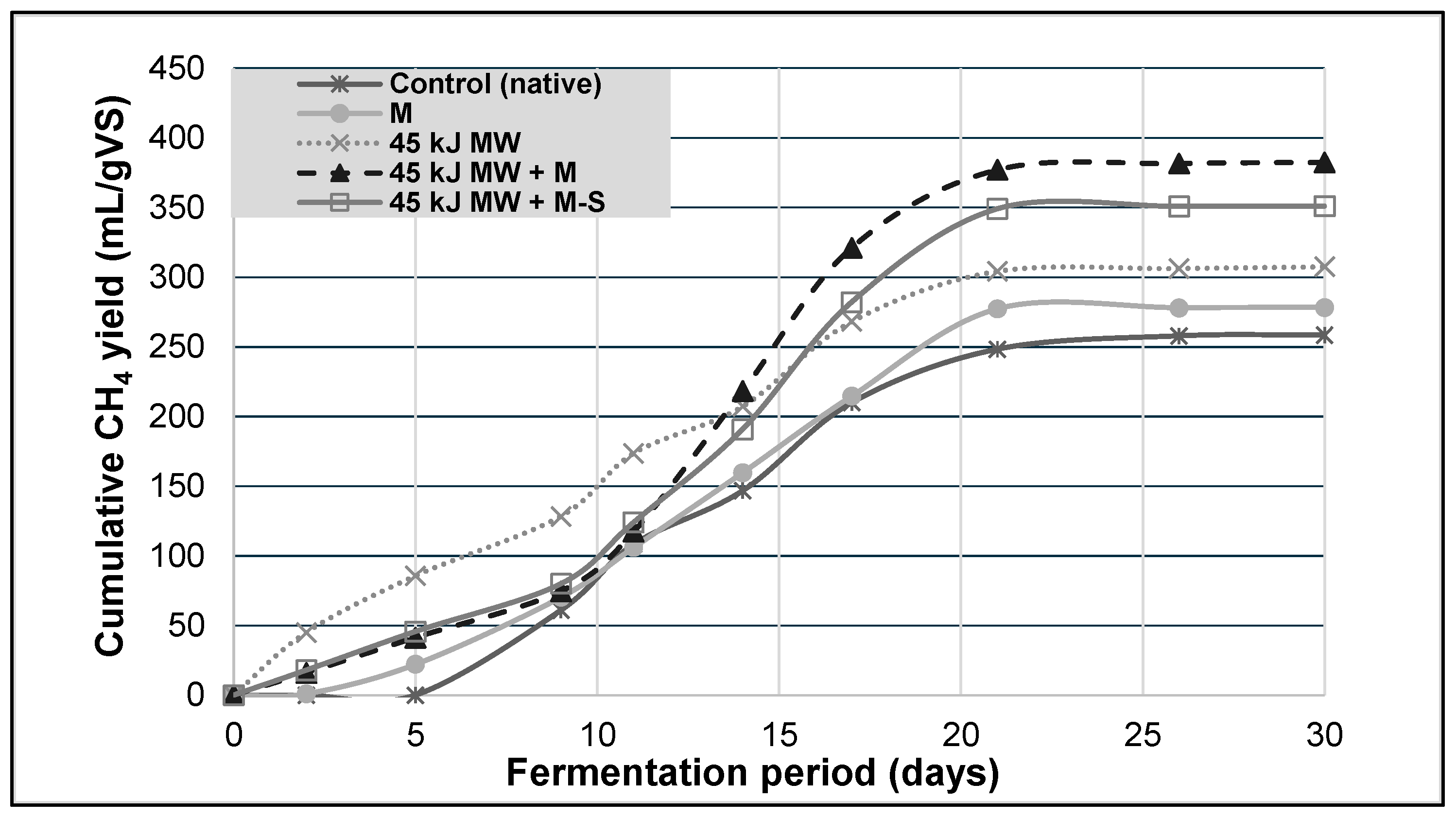

3.1. Biomethane Production

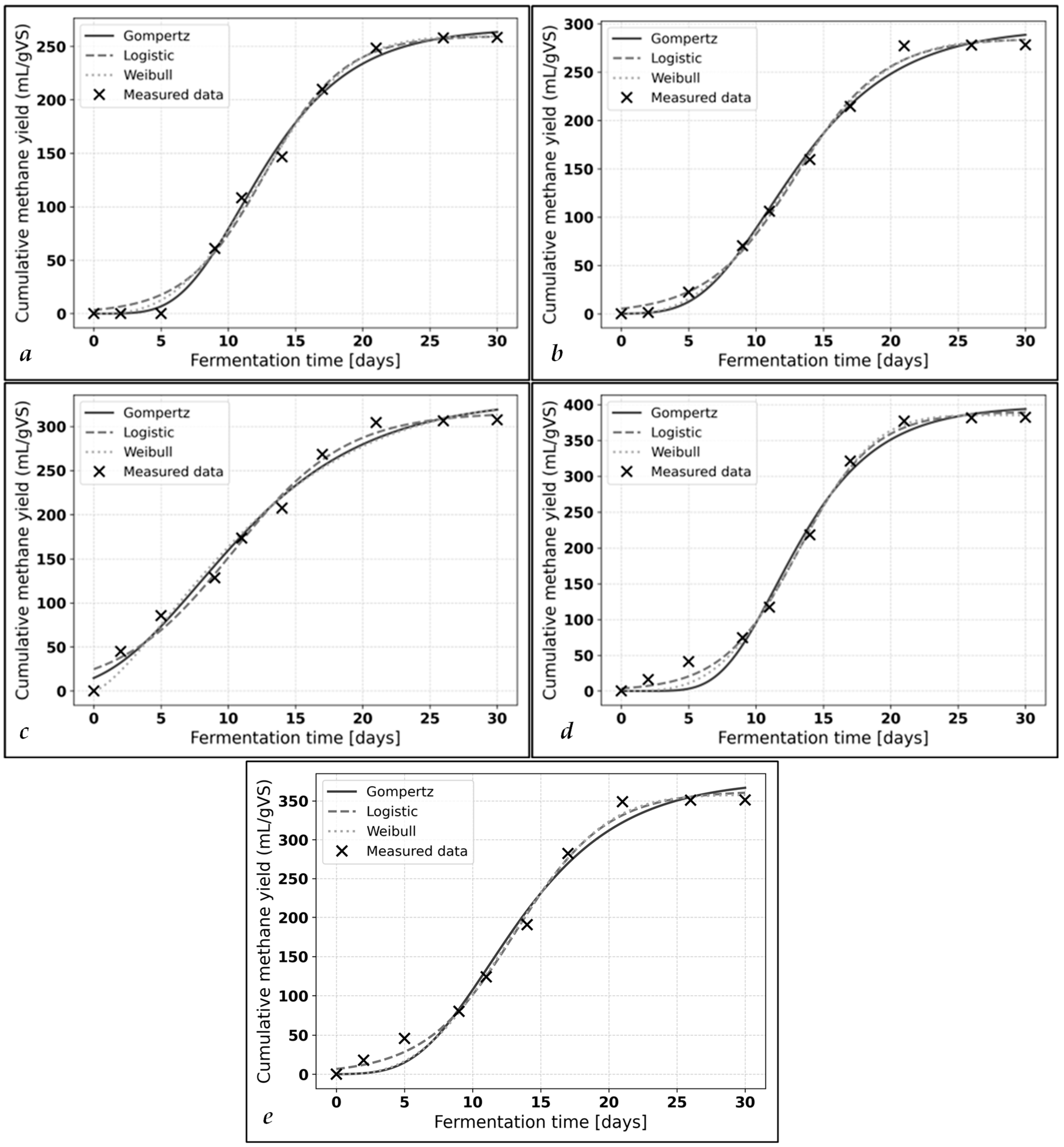

3.2. Biokinetic Analysis

3.3. Comparison with Literature Data

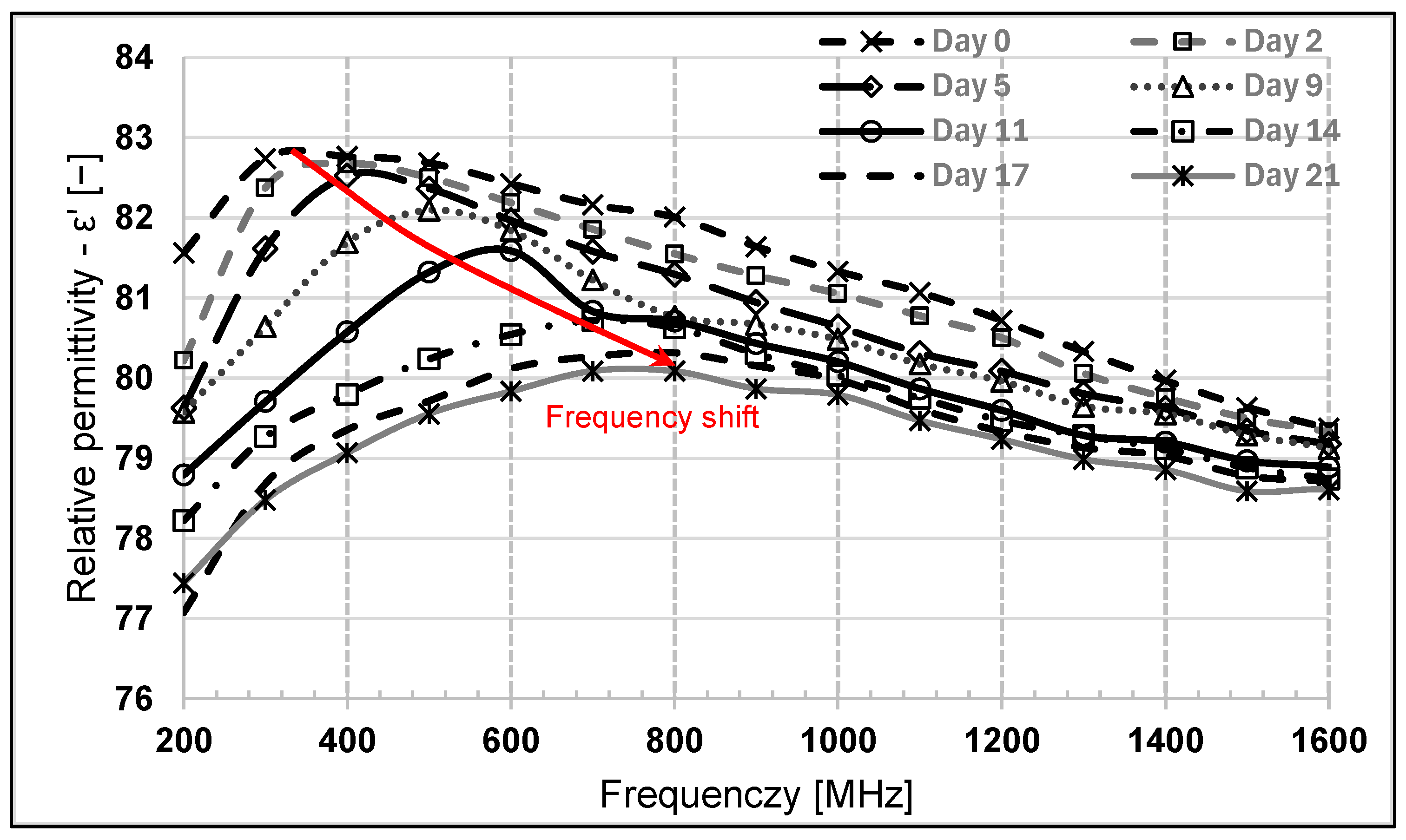

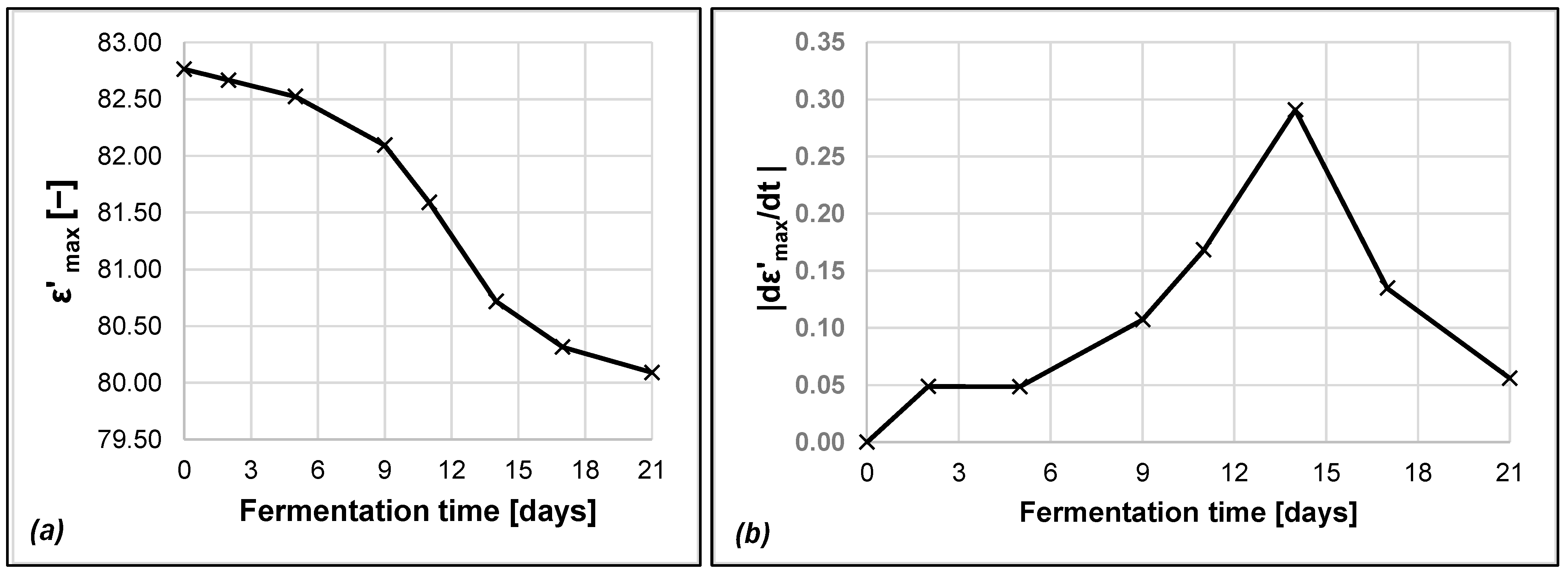

3.4. Dielectric Analysis

4. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Anaerobic digestion |

| BDI | Biodegradability index |

| BMP | Biomethane potential |

| BMPexp | Measured BMP (i.e., maximum biomethane yield) |

| BMPth | Theoretical maximum BMP (biomethane yield) |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| gVS | Unit mass (gram) of volatile solids |

| MP | Magnetic nanoparticles |

| mL CH4 | Amount (volume) of biomethane formed/produced |

| MW | Microwave (irradiation) |

| MWE | Microwave energy |

| Pmax | Maximum product (in our case, biomethane) |

| Rmax | Maximum product formation rate |

| sCOD | Soluble COD |

| tCOD | Total COD |

| tmax | Time it takes to reach Rmax (exclusive to the Weibull model) |

| TS | Total solids |

| VS | Volatile solids |

| λ | Length of the lag-phase or time it takes to reach Rmax |

| Relative permittivity | |

| Maximum value of the relative permittivity |

Appendix A

| Sample | Model | Pmax | Rmax | N | λ or tmax | R2 | RMSE | AIC | ΔAIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Gompertz | 267.276 | 21.708 | - | 6.362 | 0.996 | 6.610 | 72.150 | 0.717 | 73.058 |

| Control | Logistic | 259.880 | 22.111 | - | 6.822 | 0.993 | 8.642 | 77.513 | 6.079 | 78.420 |

| Control | Weibull | 259.456 | 20.344 | 2.852 | 12.337 | 0.996 | 6.377 | 71.433 | 0.000 | 72.341 |

| 45 kJ MW | Gompertz | 332.211 | 17.684 | - | 0.942 | 0.987 | 12.466 | 84.838 | 1.013 | 85.746 |

| 45 kJ MW | Logistic | 316.068 | 18.794 | - | 1.949 | 0.988 | 11.850 | 83.825 | 0.000 | 84.733 |

| 45 kJ MW | Weibull | 334.647 | 18.475 | 1.397 | 5.409 | 0.984 | 13.932 | 87.062 | 3.237 | 87.970 |

| 45 kJ MW + M | Gompertz | 398.222 | 35.580 | - | 7.361 | 0.988 | 16.683 | 90.667 | 11.637 | 91.575 |

| 45 kJ MW + M | Logistic | 390.056 | 34.743 | - | 7.507 | 0.996 | 9.324 | 79.030 | 0.000 | 79.937 |

| 45 kJ MW + M | Weibull | 385.319 | 34.065 | 3.327 | 13.078 | 0.994 | 11.853 | 83.831 | 4.801 | 84.738 |

| M | Gompertz | 296.122 | 20.965 | - | 5.802 | 0.994 | 8.746 | 77.751 | 7.386 | 78.658 |

| M | Logistic | 285.089 | 21.886 | - | 6.434 | 0.996 | 6.803 | 72.725 | 2.360 | 73.633 |

| M | Weibull | 283.563 | 20.615 | 2.675 | 12.316 | 0.997 | 6.045 | 70.365 | 0.000 | 71.273 |

| 45 kJ MW + M-S | Gompertz | 377.734 | 26.129 | - | 5.902 | 0.985 | 16.652 | 90.630 | 10.143 | 91.537 |

| 45 kJ MW + M-S | Logistic | 362.667 | 27.362 | - | 6.523 | 0.995 | 10.028 | 80.486 | 0.000 | 81.394 |

| 45 kJ MW + M-S | Weibull | 357.933 | 26.893 | 2.808 | 12.642 | 0.991 | 13.056 | 85.763 | 5.277 | 86.671 |

Appendix B

References

- Appels, L.; Baeyens, J.; Degrève, J.; Dewil, R. Principles and Potential of the Anaerobic Digestion of Waste-Activated Sludge. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 755–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Alvarez, J.; Dosta, J.; Romero-Güiza, M.S.; Fonoll, X.; Peces, M.; Astals, S. A Critical Review on Anaerobic Co-Digestion Achievements between 2010 and 2013. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 36, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrieze, J.; Verstraete, W. Perspectives for Microbial Community Composition in Anaerobic Digestion: From Abundance and Activity to Connectivity. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 2797–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.W.; McCabe, B.K. Review of Pre-Treatments Used in Anaerobic Digestion and Their Potential Application in High-Fat Cattle Slaughterhouse Wastewater. Appl. Energy 2015, 155, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, R.; Saady, N.M.C.; Torrijos, M.; Thanikal, J.V.; Hung, Y.-T. Sustainable Agro-Food Industrial Wastewater Treatment Using High Rate Anaerobic Process. Water 2013, 5, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitk, P.; Kaparaju, P.; Vilu, R. Methane Potential of Sterilized Solid Slaughterhouse Wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 116, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.-H.; Shin, S.G.; Hwang, S. Effect of Microwave Irradiation on the Disintegration and Acidogenesis of Municipal Secondary Sludge. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 153, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jákói, Z.; Lemmer, B.; Hodúr, C.; Beszédes, S. Microwave and Ultrasound Based Methods in Sludge Treatment: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vialkova, E.; Obukhova, M.; Belova, L. Microwave Irradiation in Technologies of Wastewater and Wastewater Sludge Treatment: A Review. Water 2021, 13, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskicioglu, C.; Prorot, A.; Marin, J.; Droste, R.L.; Kennedy, K.J. Synergetic Pretreatment of Sewage Sludge by Microwave Irradiation in Presence of H2O2 for Enhanced Anaerobic Digestion. Water Res. 2008, 42, 4674–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beszédes, S.; László, Z.; Szabó, G.; Hodúr, C. Effects of Microwave Pretreatments on the Anaerobic Digestion of Food Industrial Sewage Sludge. Environ. Prog. Amp; Sustain. Energy 2010, 30, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariunbaatar, J.; Panico, A.; Esposito, G.; Pirozzi, F.; Lens, P.N.L. Pretreatment Methods to Enhance Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Solid Waste. Appl. Energy 2014, 123, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demianchuk, B.; Guliiev, S.; Ugol’nikov, A.; Kliat, Y.; Kosenko, A. Development of Microwave Technology of Selective Heating the Components of Heterogeneous Media. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2022, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Wang, J. Pretreatment of Sludge by Ionizing Radiation for Enhanced Methane Production in Anaerobic Digestion: Effect of Antibiotics and Variation in Bacterial and Archaeal Community. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2026, 242, 113581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.-S.; Kang, H. Electron Beam Pretreatment of Sewage Sludge Before Anaerobic Digestion. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2003, 109, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemée, L.; Collard, M.; Vel Leitner, N.K.; Teychené, B. Changes in Wastewater Sludge Characteristics Submitted to Thermal Drying, E-Beam Irradiation or Anaerobic Digestion. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ano, T.; Tsubaki, S.; Fujii, S.; Wada, Y. Designing Local Microwave Heating of Metal Nanoparticles/Metal Oxide Substrate Composites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 23720–23728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Bai, X.; Abdelsayed, V.; Shekhawat, D.; Muley, P.D.; Karpe, S.; Mevawala, C.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Robinson, B.; Caiola, A.; et al. Microwave-Assisted Conversion of Methane over H-(Fe)-ZSM-5: Evidence for Formation of Hot Metal Sites. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 129670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, Y.; Drennan, C.L. A Role for Nickel–Iron Cofactors in Biological Carbon Monoxide and Carbon Dioxide Utilization. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallenbeck, P. Biological Hydrogen Production; Fundamentals and Limiting Processes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2002, 27, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yuan, R.; Liu, C.; Zhou, B. Effect of Fe2+ Adding Period on the Biogas Production and Microbial Community Distribution during the Dry Anaerobic Digestion Process. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 136, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, X.; Chen, S. Enhanced Anaerobic Digestion of Waste Activated Sludge Digestion by the Addition of Zero Valent Iron. Water Res. 2014, 52, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; He, X.; Lu, H.; Wei, N.; Zhang, J. Effect of Iron Supplementation On The Biogas Production and Microbial Community Distribution During Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste Process. Res. Sq. Platf. LLC 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadianroshanfekr, M.; Pazoki, M.; Pejman, M.B.; Ghasemzadeh, R.; Pazoki, A. Kinetic Modeling and Optimization of Biogas Production from Food Waste and Cow Manure Co-Digestion. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, K.; Zheng, L.; Han, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, L. Modelling Biogas Production Kinetics of Various Heavy Metals Exposed Anaerobic Fermentation Process Using Sigmoidal Growth Functions. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 11, 4837–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelif Ibro, M.; Ramayya Ancha, V.; Beyene Lemma, D. Biogas Production Optimization in the Anaerobic Codigestion Process: A Critical Review on Process Parameters Modeling and Simulation Tools. J. Chem. 2024, 2024, 4599371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Cosío, G.; Herrera-López, E.J.; Arellano-Plaza, M.; Gschaedler-Mathis, A.; Kirchmayr, M.; Amaya-Delgado, L. Application of Dielectric Spectroscopy to Unravel the Physiological State of Microorganisms: Current State, Prospects and Limits. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 6101–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Xin, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Fu, H.; Wang, Y. Dielectric Properties of Yogurt for Online Monitoring of Fermentation Process. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018, 11, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobozi, R.; Jákói, Z.P.; Csanádi, J.; Beszédes, S. Investigating the Acid- and Enzyme-Induced Coagulation of Raw Milk Using Dielectric and Rheological Measurements. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illés, E.; Szekeres, M.; Tóth, I.Y.; Szabó, Á.; Iván, B.; Turcu, R.; Vékás, L.; Zupkó, I.; Jaics, G.; Tombácz, E. Multifunctional PEG-Carboxylate Copolymer Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Application. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 451, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illés, E.; Tombácz, E. The Effect of Humic Acid Adsorption on pH-Dependent Surface Charging and Aggregation of Magnetite Nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 295, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal Syaichurrozi, B.; Sumardiono, S. Kinetic Model of Biogas Yield Production from Vinasse at Various Initial pH: Comparison between Modified Gompertz Model and First Order Kinetic Model. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2014, 7, 2798–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, A.; Power, N. Modelling Methane Production Kinetics of Complex Poultry Slaughterhouse Wastes Using Sigmoidal Growth Functions. Renew. Energy 2017, 104, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.D.; Silva, J.R.; Castro, L.M.; Quinta-Ferreira, R.M. Kinetic Prediction of Biochemical Methane Potential of Pig Slurry. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madondo, N.I.; Rathilal, S.; Bakare, B.F.; Tetteh, E.K. Application of Magnetite-Nanoparticles and Microbial Fuel Cell on Anaerobic Digestion: Influence of External Resistance. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakam Nguenouho, O.S.; Chevalier, A.; Potelon, B.; Benedicto, J.; Quendo, C. Dielectric Characterization and Modelling of Aqueous Solutions Involving Sodium Chloride and Sucrose and Application to the Design of a Bi-Parameter RF-Sensor. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Measured Value |

|---|---|

| Total solids (TS) | 89.1 ± 2.1 g/L (8.91 w/w%) |

| Volatile solids (VS) | 67.6 ± 1.9 g/L (6.76 w/w%) |

| pH | 6.1 ± 0.2 |

| Total chemical oxygen demand (tCOD) | 97.17 ± 3.8 g/L |

| Soluble COD (sCOD) | 19.2 ± 0.8 g/L |

| Irradiated Total Microwave Energy (MWE) | Magnetic Nanoparticles | Sample Code Name |

|---|---|---|

| - | - | Control |

| - | 5 mg, kept during the AD | M |

| 45 kJ | - | 45 kJ MW |

| 45 kJ | 5 mg, removed prior to AD | 45 kJ MW + M-S 1 |

| 45 kJ | 5 mg, kept during the AD | 45 kJ MW + M |

| Sample | Best Kinetic Model | Rmax [mL CH4/gVS·Day] | Pmax [mL CH4/gVS] | * or λ ** [Days] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Weibull | 20.344 | 259.456 | 12.337 |

| M | Weibull | 20.615 | 283.563 | 12.315 |

| 45 kJ MW | Logistic | 18.798 | 316.068 | 1.949 |

| 45 kJ MW + M | Logistic | 37.743 | 390.056 | 7.507 |

| 45 kJ MW + M-S | Logistic | 27.361 | 362.667 | 6.522 |

| Study | Substrate | Pre-Treatment/Additive | BMP (mL CH4/gVS) | [mL CH4/gVS/Day] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | Meat-processing sludge | 45 kJ MW + magnetite MPs (retained in AD) | 390 | 38 | Best fit: logistic model |

| Ware & Power, 2017 [33] | Poultry slaughterhouse waste | None (control AD) | 260–595 | 32–46 | Sigmoidal kinetic modeling |

| Pitk et al., 2012 [6] | Flotation sludge | Thermal sterilization | 650 | n.r. | 131 m3 CH4/t production |

| Feng et al., 2014 [22] | Waste activated sludge | Zero-valent iron (ZVI) | 193—276 | n.r. | Iron-mediated enhancement |

| Wang et al., 2020 [21] | Dry AD sludge | Fe2+ supplementation | 220–685 | 7–24 | Iron-driven microbial effects |

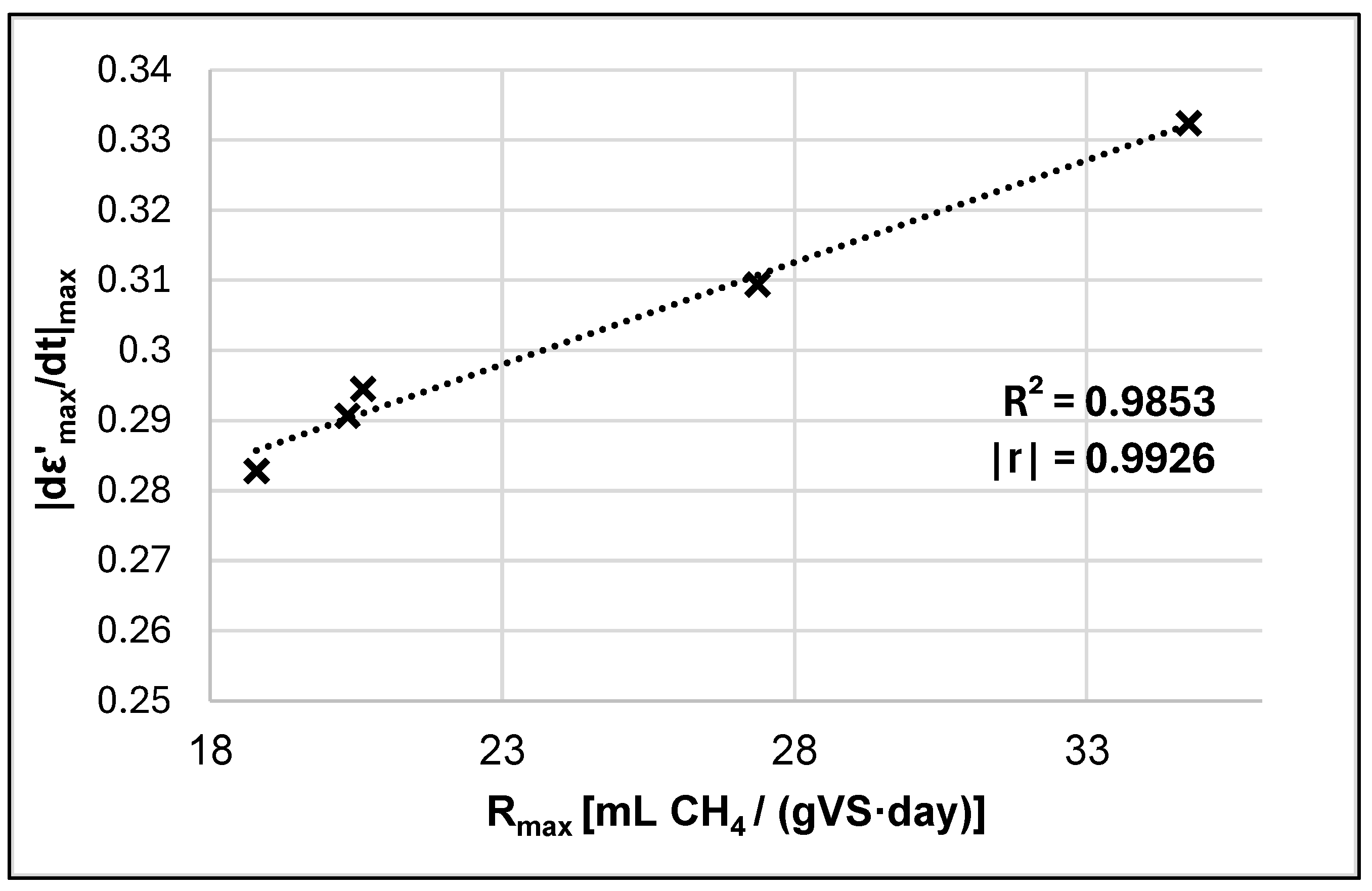

| Sample | Rmax [mL CH4/(gVS·Day)] | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.2907 | 20.344 |

| MP only (M) | 0.2945 | 20.615 |

| 45 kJ MW | 0.2818 | 18.798 |

| 45 kJ MW + M | 0.3324 | 37.743 |

| 45 kJ MW + M-S | 0.3094 | 27.361 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jákói, Z.P.; Illés, E.; Dobozi, R.; Beszédes, S. Using Biokinetic Modeling and Dielectric Monitoring to Assess Anaerobic Digestion of Meat-Processing Sludge Pretreated with Microwave Irradiation and Magnetic Nanoparticles. Water 2026, 18, 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030293

Jákói ZP, Illés E, Dobozi R, Beszédes S. Using Biokinetic Modeling and Dielectric Monitoring to Assess Anaerobic Digestion of Meat-Processing Sludge Pretreated with Microwave Irradiation and Magnetic Nanoparticles. Water. 2026; 18(3):293. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030293

Chicago/Turabian StyleJákói, Zoltán Péter, Erzsébet Illés, Réka Dobozi, and Sándor Beszédes. 2026. "Using Biokinetic Modeling and Dielectric Monitoring to Assess Anaerobic Digestion of Meat-Processing Sludge Pretreated with Microwave Irradiation and Magnetic Nanoparticles" Water 18, no. 3: 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030293

APA StyleJákói, Z. P., Illés, E., Dobozi, R., & Beszédes, S. (2026). Using Biokinetic Modeling and Dielectric Monitoring to Assess Anaerobic Digestion of Meat-Processing Sludge Pretreated with Microwave Irradiation and Magnetic Nanoparticles. Water, 18(3), 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030293