High-Resolution Monitoring of Badland Erosion Dynamics: Spatiotemporal Changes and Topographic Controls via UAV Structure-from-Motion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

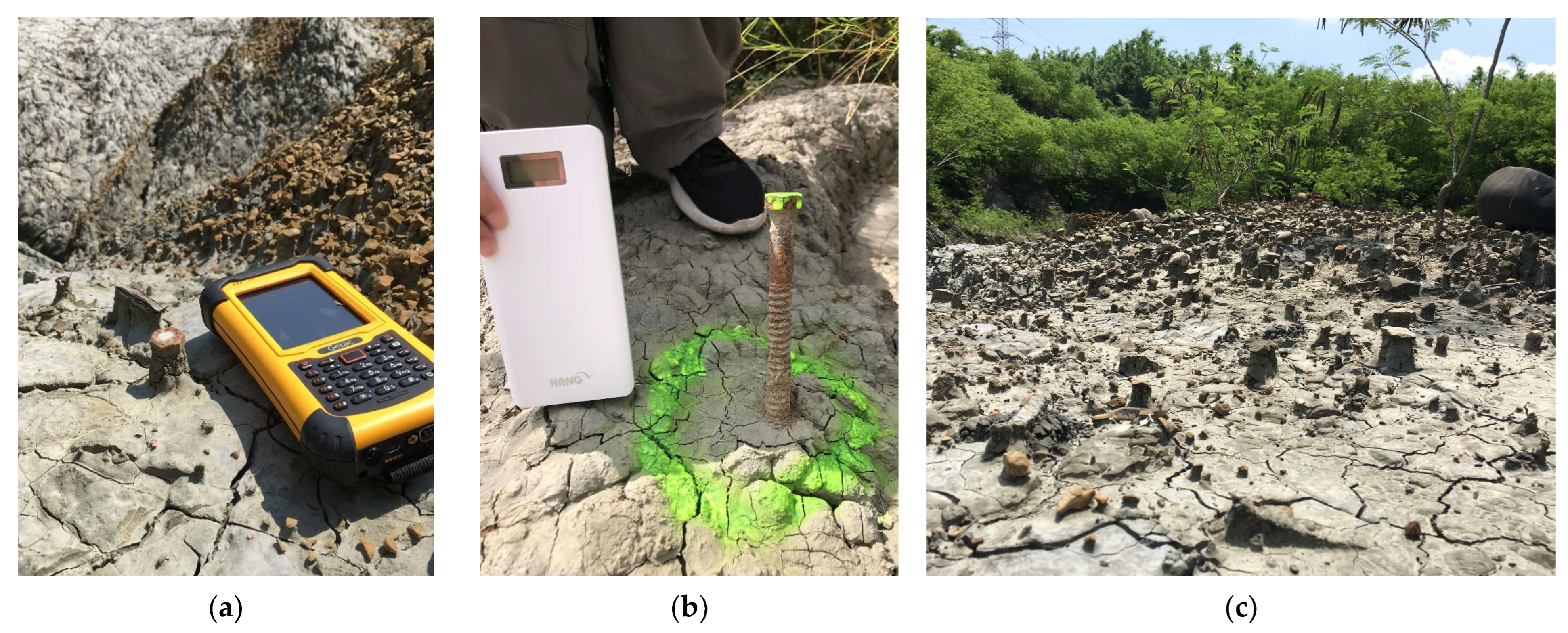

2.2. UAV Surveys and Ground Control Points

2.3. SfM-MVS Process

2.4. Uncertainty Analysis

2.5. Topographic Analysis and Gully Morphology

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy Assessment of DSMs

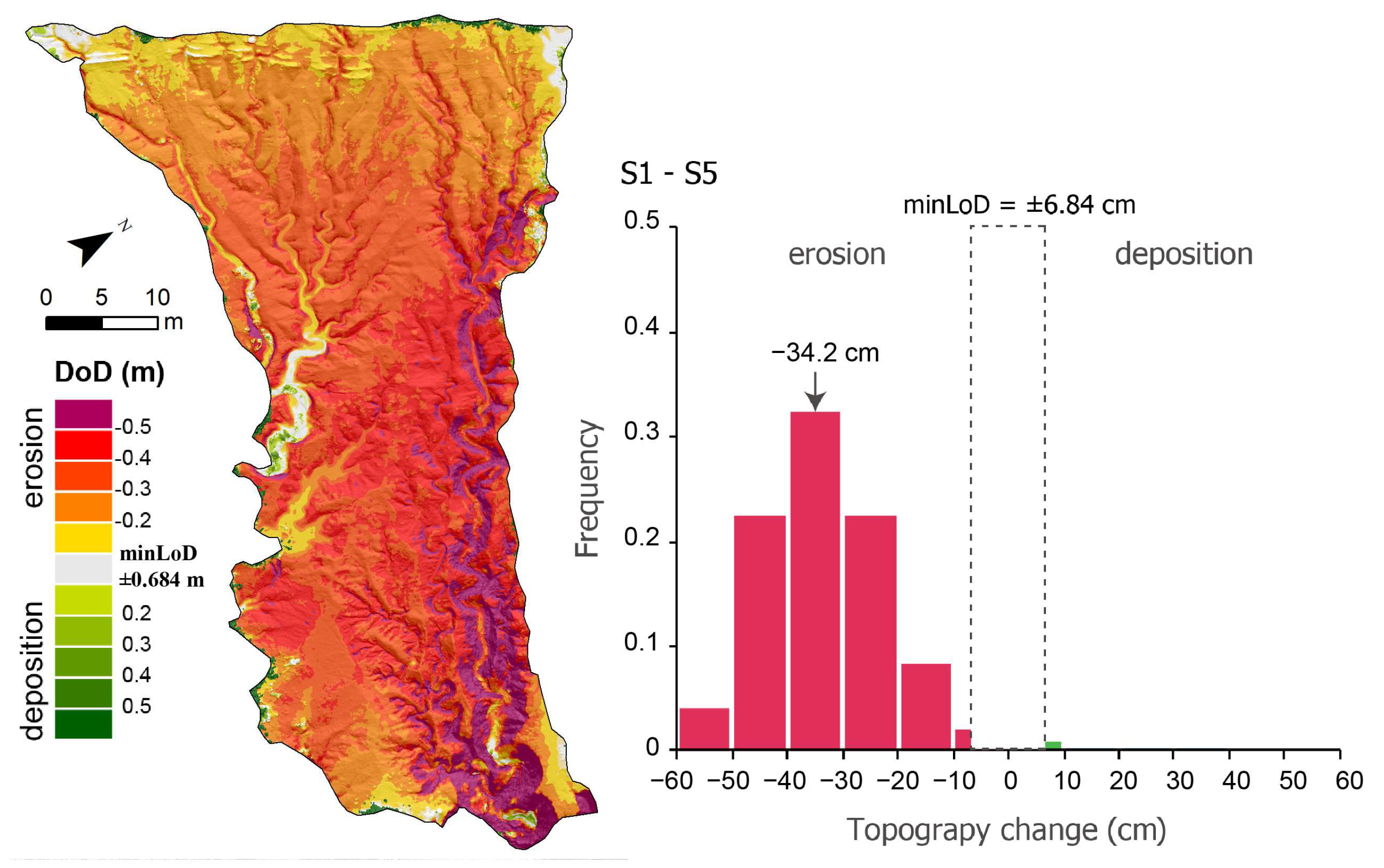

3.2. Topographic Changes Driven by Rainfall Events

3.3. Topographic Factors on Erosion

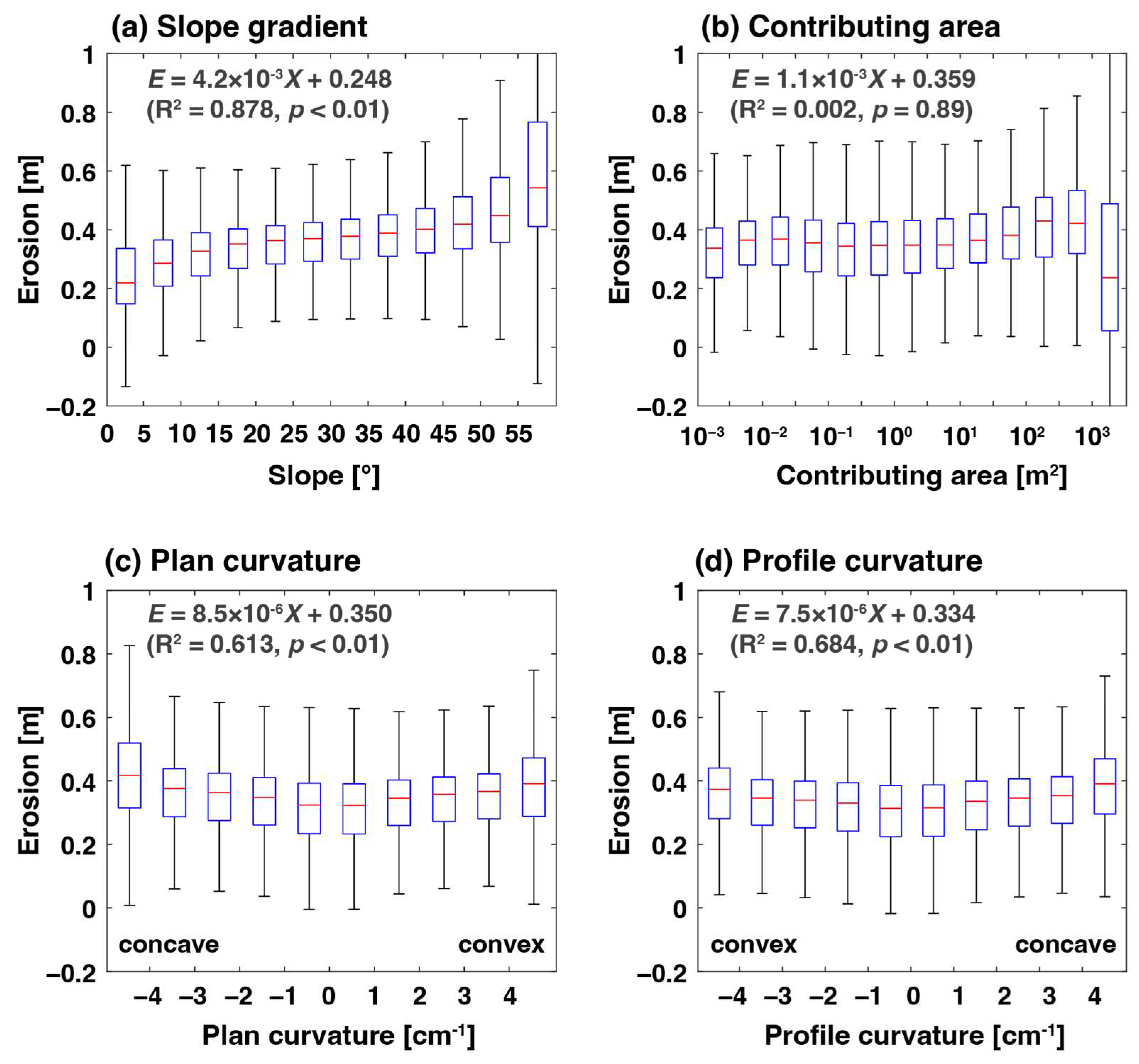

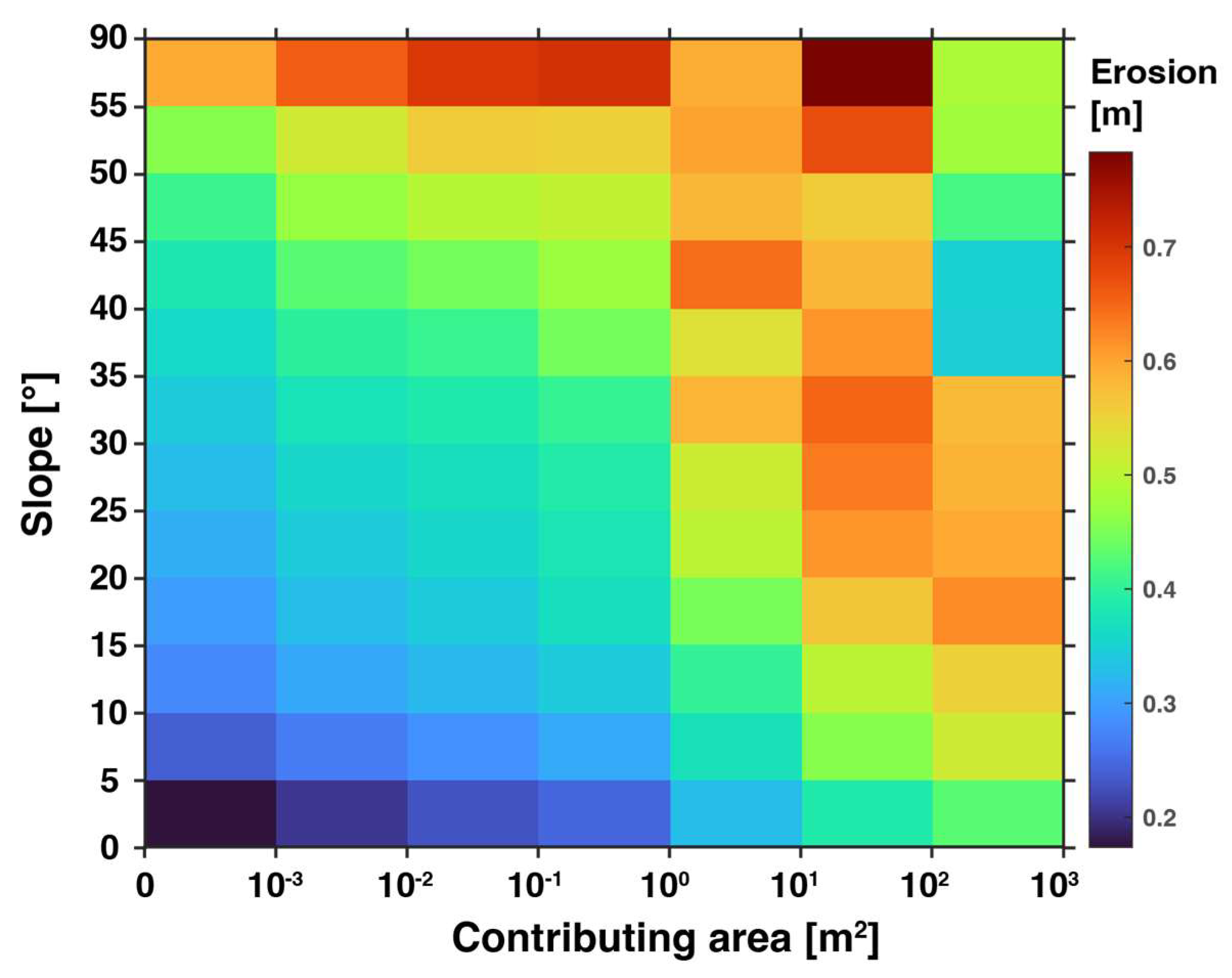

4. Discussion

4.1. Erosion Rate on the Mudstone Badlands

4.2. Morphological Dynamics of Gully Network

- Watershed (a): This largest sub-catchment connects directly to the rapidly incising main channel, providing the lowest local base level. Devoid of vegetation barriers, it exhibits the highest average erosion rate of 24.8 cm yr−1, driven by downstream channel incision.

- Watershed (b): Although the second largest in area, its outlet is obstructed by dense vegetation. This creates a raised local base level that impedes sediment export and promotes localized deposition in the downstream reaches. Consequently, this watershed shows the lowest erosion rate of 16.1 cm yr−1, demonstrating how vegetation can decouple upstream production from downstream export.

- Watershed (c): This intermediate watershed drains near the active gully zone but is partially constrained by vegetation. It exhibits an intermediate erosion rate of 19.8 cm yr−1.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SfM-MVS | Structure-from-Motion Multi-View Stereo |

| GCP | Ground Control Point |

| IGP | independent check point |

| minLoD | minimum level of detection |

| DoD | DSMs of Difference |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

References

- Howard, A.D.; Kerby, G. Channel changes in badlands. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1983, 94, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, W. The convex profile of bad-land divides. Science 1892, 20, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.W.; Vericat, D. From experimental plots to experimental landscapes: Topography, erosion and deposition in sub-humid badlands from Structure-from-Motion photogrammetry. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2015, 40, 1656–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.P. The badlands of Italy: A vanishing landscape? Appl. Geogr. 1998, 18, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhi, A.; Harris, A.; Evans, M.; Shuttleworth, E. Gullies and badlands of India: Genesis, geomorphology and land management. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 82–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Srivastava, P.; Kumar, K.; Yadav, M.; Sharma, A. Control on the evolution of badlands and their erosional dynamics, Central Narmada Basin, India. Catena 2024, 238, 107867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, K.; Chigira, M.; Lee, D.-H. High rates of erosion and rapid weathering in a Plio-Pleistocene mudstone badland, Taiwan. Catena 2013, 106, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-J.; Turowski, J.M.; Hovius, N.; Lin, J.-C.; Chang, K.-J. Badland landscape response to individual geomorphic events. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumm, S.A. Evolution of drainage systems and slopes in badlands at Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1956, 67, 597–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-J.; Turowski, J.M.; Gailleton, B.; Tseng, C.-W.; Chao, C.-M.; Chuang, R.Y. Badland distribution as a marker of rapid tectonic activity. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-J.; Tsai, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-T. Anthropogenic disruption of sediment connectivity by embankment dams in the fast-eroding badland basin. Geomorphology 2025, 488, 109981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhi, A.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Harris, A.; Evans, M.; Shuttleworth, E. Gully erosion is a serious obstacle in India’s land degradation neutrality mission. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Romero, E.; Torri, D.; Yair, A. Updating the badlands experience. Catena 2013, 106, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergari, F.; Della Seta, M.; Del Monte, M.; Barbieri, M. Badlands denudation “hot spots”: The role of parent material properties on geomorphic processes in 20-years monitored sites of Southern Tuscany (Italy). Catena 2013, 106, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcıoğlu, A.; Kašanin-Grubin, M.; Antić, N.; Moreno de las Heras, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Schwanghart, W.; Yetemen, O.; Tosti, T.; Dojčinović, B.; Görüm, T. How does climate seasonality influence weathering processes in badland landscapes? Catena 2024, 243, 108136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, N.; Kašanin-Grubin, M.; Bertalan, L.; Gajić, V.; Kaluđerović, L.; Mijatović, N.; Jovančićević, B. Are volcaniclastics bad enough to make badlands? Catena 2024, 246, 108448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-J.; Yeh, L.-W.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Jen, C.-H.; Lin, J.-C. Badland Erosion and Its Morphometric Features in the Tropical Monsoon Area. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torra, O.; Puig-Polo, C.; Hürlimann, M.; Latron, J. Analysis of erosive processes and erosion rate by in-situ measurements and multi-temporal TLS surveys in a mountainous badland area, Vallcebre (Spain). Catena 2025, 249, 108622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccarreta, M.; Prosser, G.; Bentivenga, M. Morphometric Analysis and Evolutionary Implications of Badland Basins in Southern Italy. Water 2026, 18, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, G.; Nicosia, A.; Palmeri, V.; Ferro, V. Evaluating the effect of the actual eroded badland area on the estimate of eroded volume in Italian calanchi areas. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 4081–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefano, C.D.; Ferro, V.; Porto, P.; Tusa, G. Slope curvature influence on soil erosion and deposition processes. Water Resour. Res. 2000, 36, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, M.D.; Mudd, S.M.; Walcott, R.; Attal, M.; Yoo, K. Using hilltop curvature to derive the spatial distribution of erosion rates. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2012, 117, F02017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clubb, F.J.; Mudd, S.M.; Attal, M.; Milodowski, D.T.; Grieve, S.W.D. The relationship between drainage density, erosion rate, and hilltop curvature: Implications for sediment transport processes. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2016, 121, 1724–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struble, W.T.; Clubb, F.J.; Roering, J.J. Regional-scale, high-resolution measurements of hilltop curvature reveal tectonic, climatic, and lithologic controls on hillslope morphology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2024, 647, 119044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimsath, A.M.; Dietrich, W.E.; Nishiizumi, K.; Finkel, R.C. The soil production function and landscape equilibrium. Nature 1997, 388, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.R.; Dietrich, W.E. A physically based model for the topographic control on shallow landsliding. Water Resour. Res. 1994, 30, 1153–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, R.; Yair, A. Badland Geomorphology and Piping; Geo Books: Norwich, UK, 1982; p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier, G.; Van De Wiel, M.J.; De Clercq, W.P. Intersecting views of gully erosion in South Africa. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2023, 48, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeri, V.; Di Stefano, C.; Guida, G.; Nicosia, A.; Ferro, V. Monitoring the temporal evolution of a Sicilian badland area by unmanned aerial vehicles. Geomorphology 2024, 466, 109443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, S.P.; Fonte, S.J.; García, E.; Smukler, S.M. Improving the utility of erosion pins: Absolute value of pin height change as an indicator of relative erosion. Catena 2018, 163, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, V.; Sahour, H.; Amri, M.A.H. Soil erosion modeling using erosion pins and artificial neural networks. Catena 2021, 196, 104902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Romero, E.; Martínez-Murillo, J.F.; Vanmaercke, M.; Poesen, J. Scale-dependency of sediment yield from badland areas in Mediterranean environments. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2011, 35, 297–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, T. Estimating soil loss from medium-size drainage basins. Phys. Geogr. 1992, 13, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, J.C.L.; Heggy, E. Measuring soil moisture change and surface erosion from sparse rainstorms in hyper-arid terrains. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 142, 104642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacicco, R.; La Salandra, M.; Lapietra, I.; Refice, A.; Capolongo, D. Remote sensing techniques to assess badlands dynamics: Insights from a systematic review. GIScience Remote Sens. 2025, 62, 2516347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, J.L.; Corona, C.; Stoffel, M.; Rovéra, G.; Astrade, L.; Berger, F. Mapping of erosion rates in marly badlands based on a coupling of anatomical changes in exposed roots with slope maps derived from LiDAR data. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2011, 36, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Fu, H.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Yan, L. Comparative Assessment Using Different Topographic Change Detection Algorithms for Gravity Erosion Quantification Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Water 2025, 17, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Li, J.; Zlatanova, S.; Wu, H.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, S.; Qu, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Novel UAV-based 3D reconstruction using dense LiDAR point cloud and imagery: A geometry-aware 3D gaussian splatting approach. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 140, 104590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, P.; Hu, J.; Yao, W.; Yan, L.; Fassnacht, F.E.; Latifi, H.; Dan, Y.; Liu, L.; Gao, J.; et al. Comparing methods of assessing uncertainty in DEM of difference for soil erosion detection based on UAV laser scanning data. Geomorphology 2025, 491, 110034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, P.; Hu, J.; Bai, X.; Latifi, H.; Liu, L.; Yao, W. Mapping Catchment-Scale Soil Erosion and Deposition Using an Improved DoD Method Based on Multitemporal UAV-Borne Laser Scanning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5701113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, M.M.; Degré, A.; Debouche, C.; Lisein, J. The evaluation of unmanned aerial system-based photogrammetry and terrestrial laser scanning to generate DEMs of agricultural watersheds. Geomorphology 2014, 214, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-T.; Chen, Y.-C. Channel aggradation decelerates downstream sweep erosion in Daan river Gorge, Taiwan. Geosci. Lett. 2025, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jen, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-C. Photogrammetric Reconstruction of Multi-decadal Topographic Changes from Historical Aerial Imagery for Landslide and Debris-flow Hazard Assessment. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2026, 41, 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhou, J.; Yang, X.; Gao, D.; Liu, S. Automated high-resolution 3D crevasse extraction and dynamic linkages: An integrated UAV-LiDAR, photogrammetry, and C-TransUNet framework. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 144, 104881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, V.; Fugazza, D.; Hanson, K.; Scaioni, M.; Di Rita, M. Assessing glacier thickness changes with multi-temporal UAV-derived DEMs: The evolution of Forni Glacier over the period 2014–2022. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 140, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Ke, L.; Li, Q.; Fan, J.; Wang, X. Research on Soil Erosion Based on Remote Sensing Technology: A Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Lin, H.-M.; Wu, J.-H. The basic properties of mudstone slopes in southwestern Taiwan. J. Geoengin. 2007, 2, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.-J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Ali, M.Z.; Höfle, B. Multi-Parameter Relief Map from High-Resolution DEMs: A Case Study of Mudstone Badland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Resources Agency. Hydrological Yearbook 2024 Part I—Rainfall; Water Resource Agency of Ministry of Economic Affair: Taipei, Taiwan, 2024.

- Dadson, S.J.; Hovius, N.; Chen, H.; Dade, W.B.; Hsieh, M.-L.; Willett, S.D.; Hu, J.-C.; Horng, M.-J.; Chen, M.-C.; Stark, C.P.; et al. Links between erosion, runoff variability and seismicity in the Taiwan orogen. Nature 2003, 426, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y. Erosion on Mudstone Badland. Landsc. News 2005, 22, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pix4D SA. Pix4Dmapper 4.1 User Manual; Pix4D SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1498–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Küng, O.; Strecha, C.; Fua, P.; Gurdan, D.; Achtelik, M.; Doth, K.-M.; Stumpf, J. Simplified building models extraction from ultra-light UAV imagery. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2011, 3822, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, J.M.; Brasington, J.; Darby, S.E.; Sear, D.A. Accounting for uncertainty in DEMs from repeat topographic surveys: Improved sediment budgets. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2010, 35, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, M.; Scott, T.; Masselink, G.; Russell, P.; McCarroll, R.J. Coastal embayment rotation: Response to extreme events and climate control, using full embayment surveys. Geomorphology 2019, 327, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarboton, D.G. A new method for the determination of flow directions and upslope areas in grid digital elevation models. Water Resour. Res. 1997, 33, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, I.D.; Grayson, R.B.; Ladson, A.R. Digital terrain modelling: A review of hydrological, geomorphological, and biological applications. Hydrol. Process. 1991, 5, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, I.J.; Montgomery, D.R. Landslide erosion coupled to tectonics and river incision. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francek, M. Earth pillar formation on the mountain pine ridge, Belize. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 1988, 13, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Wang, S.-F. LogiTide2DEM: A method for reconstructing intertidal topography in complex tidal flats using logistic regression with multi-temporal Sentinel-2 and Landsat imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 139, 104561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Chang, K.-T.; Wang, S.-F.; Ho, J.-Y.; Chen, J.-P. Influences of channel-hillslope characteristics on landslide erosion in meandering bedrock rivers. Catena 2024, 245, 108327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.R. Slope distributions, threshold hillslopes, and steady-state topography. Am. J. Sci. 2001, 301, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipple, K.X.; Tucker, G.E. Dynamics of the stream-power river incision model: Implications for height limits of mountain ranges, landscape response timescales, and research needs. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1999, 104, 17661–17674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergari, F.; Troiani, F.; Cavalli, M.; Faulkner, H.; Del Monte, M. Shifts in hillslope-channel connectivity after land reclamation in a Mediterranean semi-humid badland landscape. Catena 2025, 254, 108921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Date | UAV | Num. of Photos | GSD [cm] | Cover Area [m2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 2017/01/20 | DJI P3 Pro | 154 | 0.94 | 6035 |

| S2 | 2017/10/29 | DJI P4 Pro | 451 | 0.51 | 11,269 |

| S3 | 2018/02/10 | DJI P4 Pro | 2303 | 0.52 | 32,899 |

| S4 | 2018/06/27 | DJI P4 Pro | 1620 | 0.55 | 22,915 |

| S5 | 2018/10/19 | DJI P4 Pro | 2089 | 0.53 | 23,780 |

| ID | Date | Point Density [pts/m2] | GCPs RMSE [cm] | ICPs RMSE [cm] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | N | Z | Z | |||

| S1 | 2017/01/20 | 3839 | 5.89 | 6.08 | 6.19 | 5.29 |

| S2 | 2017/10/29 | 9302 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 1.21 | 1.79 |

| S3 | 2018/02/10 | 21,242 | 4.98 | 4.48 | 4.97 | 2.65 |

| S4 | 2018/06/27 | 44,587 | 2.52 | 2.86 | 2.81 | 2.37 |

| S5 | 2018/10/19 | 22,568 | 2.10 | 1.82 | 0.79 | 4.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.-C. High-Resolution Monitoring of Badland Erosion Dynamics: Spatiotemporal Changes and Topographic Controls via UAV Structure-from-Motion. Water 2026, 18, 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020234

Chen Y-C. High-Resolution Monitoring of Badland Erosion Dynamics: Spatiotemporal Changes and Topographic Controls via UAV Structure-from-Motion. Water. 2026; 18(2):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020234

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yi-Chin. 2026. "High-Resolution Monitoring of Badland Erosion Dynamics: Spatiotemporal Changes and Topographic Controls via UAV Structure-from-Motion" Water 18, no. 2: 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020234

APA StyleChen, Y.-C. (2026). High-Resolution Monitoring of Badland Erosion Dynamics: Spatiotemporal Changes and Topographic Controls via UAV Structure-from-Motion. Water, 18(2), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020234