Hydrogeochemistry of Thermal Water from Lindian Geothermal Field, Songliao Basin, NE China: Implications for Water–Rock Interactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

- The Jurassic overlies the Carboniferous–Permian basement in unconformity, with significant thickness variation. The burial depth of its top exceeds 3000 m, while the maximum burial depth of its base ranges from 4000 to 5000 m. The sedimentary lithology is complex, dominated by variegated glutenite, conglomerate, and sandstone, and intercalated with mudstone, as well as basalt, andesite, rhyolite, and tuff [6].

- The Cretaceous was deposited during the peak sedimentary period of the Songliao Basin. It is characterized by substantial sedimentary thickness and extensive distribution, with a total thickness exceeding 3000 m. It comprises the Denglouku (K1d), Quantou (K1q), Qingshankou (K2qn), Yaojia (K2y), Nenjiang (K2n), Sifangtai (K2s), and Mingshui Formation (K2m). Among these units, Members III and IV of K1q, Members II and III of K2qn, and Members II and III of K2y in the middle and lower parts of the Cretaceous constitute the primary geothermal reservoirs in the area [7].

- K1q is widely distributed in the study area and is in unconformable contact with the underlying strata. Drilling data indicate a general thickening trend from north to south, with an average thickness of approximately 700 m and a maximum thickness of 1200 m. The formation is subdivided into four members, with detailed characteristics as follows: (i) Member I: The average burial depth of the base is 2120 to 2456 m, with a thickness of 221 m. It is a fluvial sand–mudstone deposit, where mudstone is relatively well-developed vertically; (ii) Member II: Extensively distributed across the study area, the average burial depth of the base is 1790–2235 m, with a thickness of 110–190 m. The lithology is dominated by glutenite and dark mudstone—glutenite is primarily developed in WY and KY, while dark mudstone is mainly deposited in HY; (iii) Member III: Widely distributed in the area, the average burial depth of the base is 1618–2426 m, with a thickness of 58–383 m. Dark mudstone abundant in organic matter is mainly distributed in HY, with a local sedimentary thickness of up to 100 m; (iv) Member IV: Widely distributed in the study area, the average burial depth of the base is 1500–2190 m, with a thickness of 65–146 m. Sandstone deposits during this period is relatively thin, and dark mudstone is mainly distributed in the HY [6,8]. The sandstone of K1q is the thickest in the urban area of Lindian County (Central KY), while it is relatively thinner near F1 and F2 [7].

- K2qn is divided into three members: (i) Member I: Generally distributed in the area, the average burial depth of the bottom is 1400–2100 m, with a thickness of 28–130 m. The thickness of the sandstone is relatively thin, and the mudstone thickness is 25–45 m, showing a trend of being higher in the south and lower in the north, and higher in the east and lower in the west dark mudstone is mainly distributed in HY; (ii) Members II and III: Widely distributed in the area, the average burial depth of the bottom is 1360–2080 m, with a thickness of 270–445 m. The reservoir lithology is mainly siltstone and fine sandstone, dominated by fine sandstone. The sandstone sedimentary thickness is 90–130 m, increasing from northwest to southeast. The mudstone thickness is greater in the southeast than in the northwest, with the mudstone thickness in WY exceeding 80 m and that in HY exceeding 120 m. Dark mudstone is mainly distributed in the HY [3,6,7].

- K2y is divided into the following: (i) Member I: The average burial depth of the base is 1020–1740 m, with a thickness of 20–160 m. The thickness of the sandstone is small with limited distribution; (ii) Members II and III: The average burial depth of the base is 980–670 m, with a thickness of 35–155 m. The lithology is dominated by medium sandstone, siltstone, and fine sandstone. The distribution of the sandstone is relatively limited, and dark mudstone is mainly distributed in HY [3,6,7].

- The strata overlying the Craterous are mainly fluvio-lacustrine deposits, which consist of mudstone, fine sandstone, siltstone, argillaceous siltstone, sandstone, and clay. The total thickness is ca. 900–1600 m, serving as a good caprock with relatively low thermal conductivity and permeability [6,7].

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of Groundwaters

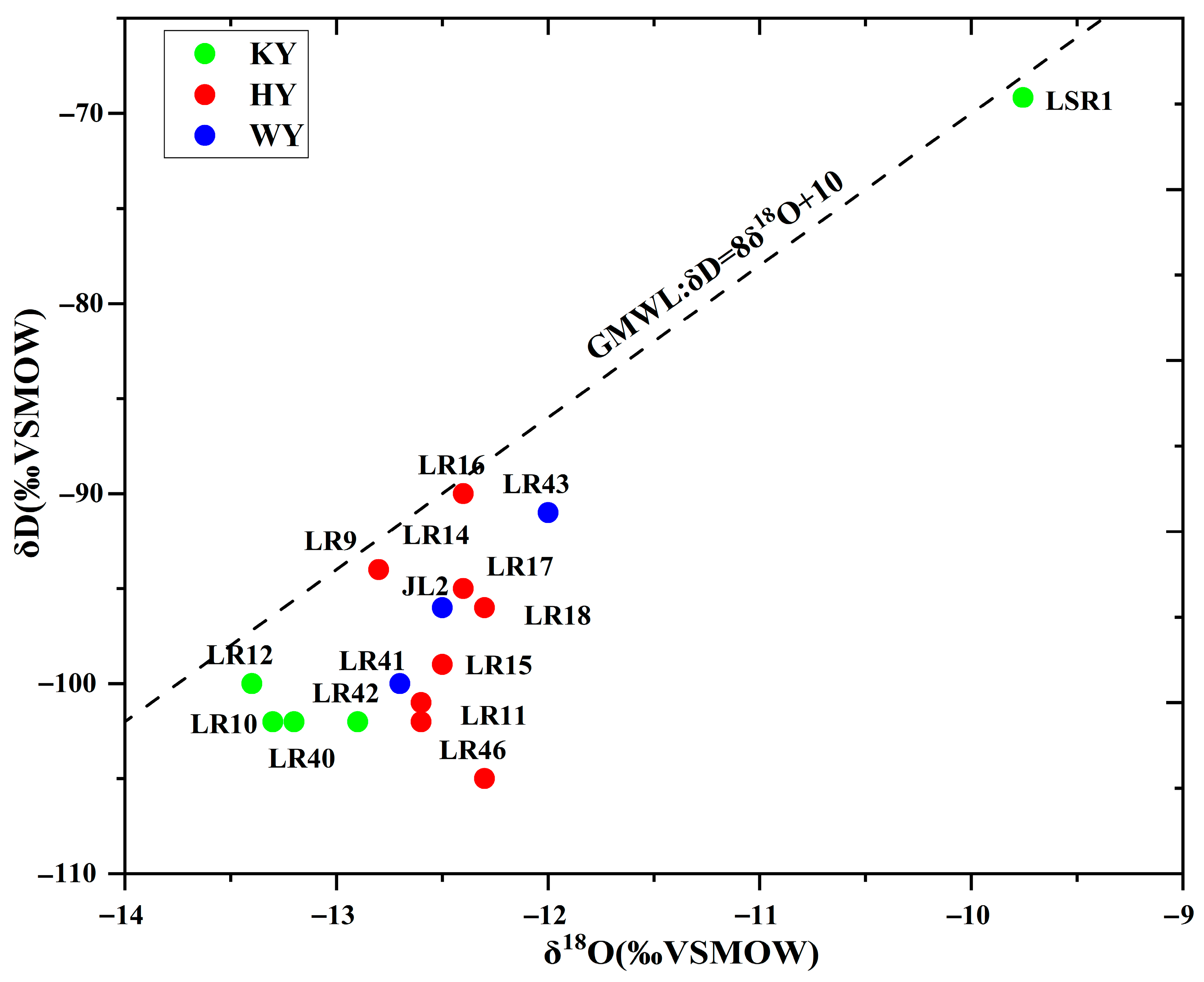

4.2. Origin of Thermal Water

4.3. Genesis of Thermal Water Chemistry

4.3.1. Leaching

- Identification from major chemical components

- 2.

- Identification from ion ratios

- 3.

- Identification from mineral stability diagram

4.3.2. Cation Exchange

4.3.3. Equilibrium of Water–Rock Interaction

4.3.4. Contribution of Various Water–Rock Interactions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Sui, X.W. Evaluation of the Geothermic Water Quality in Lindian geothermic town of Songliao Basin. J. Heilongjiang Hydraul. Eng. 2010, 37, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.S. Study on Geothermal Resources and Tourism Development Planning of Lindian County, Daqing City. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- HIHEG (Heilongjiang Institute of Hydrogeology and Engineering Geology). Report on Geothermal Energy Investigation of Lindian Geothermal Field; HIHEG: Harbin, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H.; Zhu, H.L.; Shi, S.M.; Du, X.L. Quality Evaluation of Geothermal Fluid in the Lindian Area of the Songliao Basin. Int. Energy 2023, 2, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. A Study on Seismogenic Structure of LinDian Earthquake. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.M. Study on Sedimentary Facies of Low Cretaceous in Binbei, Songliao Basin. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an Shiyou University, Xi’an, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.J. Genesis and Rational Development of Typical Geothermal Field in the Songliao Basin: A Case Study of Lindian Geothermal Field. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.N. Analysis of High Resolution Sequence Stratigraphy and Sedimentary System of Qingshankou Formatin in Heiyupao Depression and Mingshui Terrace of Songliao Basin. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shuaibu, A.; Kalin, R.M.; Phoenix, V.; Lawal, I.M. Geochemical evolution and mechanisms controlling groundwater chemistry in the transboundary Komadugu–Yobe Basin, Lake Chad region: An integrated approach of chemometric analysis and geochemical modeling. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.H.; Yang, F.T. Genesis analysis of geothermal systems in Guanzhong Basin of China with implications on sustainable geothermal resources development. In Proceedings of the World Geothermal Congress, Bali, Indonesia, 25–30 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.Q.; Xu, T.; Qiu, N.S.; Zhang, H.Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, B. Chemical characteristics and fluid origin of formation water of Bashijiqike Formation in Kelasu structure belt, Tarim basin. Acta Geol. Sin. 2023, 97, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeller, H. Qualitative evaluation of groundwater resources. In Methods and Techniques of Groundwater Investigations and Development; UNESCO: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 54–83. [Google Scholar]

- Giggenbach, W.F. Geothermal solute equilibria. Derivation of Na-K-Mg-Ca geoindicators. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1988, 52, 2749–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, P.; Liotta, M. Using and abusing Giggenbach ternary Na-K-Mg diagram. Chem. Geol. 2020, 541, 119577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, S.F. Fluid-mineral equilibria in great basin geothermal systems: Implications for chemical geothermometry. In Proceedings of Thirty-Eighth Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering Stanford University; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arnórsson, S.; Gunnlaugsson, E.; Svavarsson, H. The chemistry of geothermal waters in Iceland. II. Mineral equilibria and independent variables controlling water compositions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1983, 47, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.H.; Zheng, Z.Y.; Shao, D.L.; Wang, H.P.; Yang, L.; Wang, C.F.; Zhang, Y.G. Reviews on CO2 genesis, controlling factors of hydrocarbon and degassing model. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2021, 21, 12356–12367. [Google Scholar]

| Structural Unit | Salinity (g/L) | Main ions (meq%) | Ion Ratio (Min–Max), Average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na/Cl | 100 × SO4/C1 | Cl/(HCO3 + CO3) | C1/Ca | |||

| HY | 5.40–9.78 | Na+ (97.62%) Cl− (89.41%) HCO3− (9.59%) | 1.00–1.12, 1.07 | 0.00–0.26, 0.12 | 5.16–16.47, 9.91 | 50.69–96.63, 63.19 |

| WY | 2.01–3.47 | Na+ (99.03%) Cl− (50.35%) HCO3− (42.26%) | 1.64–2.85, 2.09 | 0.01–0.29, 0.11 | 0.58–1.47, 1.10 | 68.34–79.97, 72.49 |

| KY | 1.87–4.38 | Na+ (97.62%) Cl− (50.13%) HCO3− (43.96%) | 1.06–4.07, 2.63 | 0.12–1.09, 0.57 | 0.33–7.95, 2.57 | 13.37–55.85, 34.08 |

| Physiochemical Parameter | F1 | F2 | F3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | 0.162 | 0.843 | −0.033 |

| TDS | 0.984 | −0.080 | 0.029 |

| pH | −0.806 | −0.387 | 0.005 |

| SiO2 | 0.685 | 0.594 | 0.238 |

| Na+ | 0.985 | −0.073 | 0.043 |

| K+ | 0.878 | −0.045 | 0.218 |

| Ca2+ | 0.853 | −0.290 | −0.010 |

| Mg2+ | 0.677 | 0.059 | 0.235 |

| Cl− | 0.983 | −0.0152 | −0.002 |

| HCO3− | −0.500 | 0.730 | 0.348 |

| CO32− | −0.779 | −0.080 | 0.519 |

| SO42− | −0.016 | 0.381 | −0.859 |

| Eigenvalue | 6.866 | 2.022 | 1.291 |

| Variance% | 57.213 | 16.848 | 10.757 |

| The cumulative variance% | 57.213 | 74.061 | 84.818 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Su, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhou, X.; Dong, J.; Liu, L.; Ma, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, C. Hydrogeochemistry of Thermal Water from Lindian Geothermal Field, Songliao Basin, NE China: Implications for Water–Rock Interactions. Water 2026, 18, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010090

Su Y, Yang F, Zhou X, Dong J, Liu L, Ma Y, Chen M, Zhang C. Hydrogeochemistry of Thermal Water from Lindian Geothermal Field, Songliao Basin, NE China: Implications for Water–Rock Interactions. Water. 2026; 18(1):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010090

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Yujuan, Fengtian Yang, Xuejun Zhou, Junling Dong, Ling Liu, Yongfa Ma, Minghua Chen, and Chaoyu Zhang. 2026. "Hydrogeochemistry of Thermal Water from Lindian Geothermal Field, Songliao Basin, NE China: Implications for Water–Rock Interactions" Water 18, no. 1: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010090

APA StyleSu, Y., Yang, F., Zhou, X., Dong, J., Liu, L., Ma, Y., Chen, M., & Zhang, C. (2026). Hydrogeochemistry of Thermal Water from Lindian Geothermal Field, Songliao Basin, NE China: Implications for Water–Rock Interactions. Water, 18(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010090