Settlement Induction in Mytilus coruscus Is Driven by Cue Diversity: Evidence from Natural Biofilms and Bacterial Isolates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

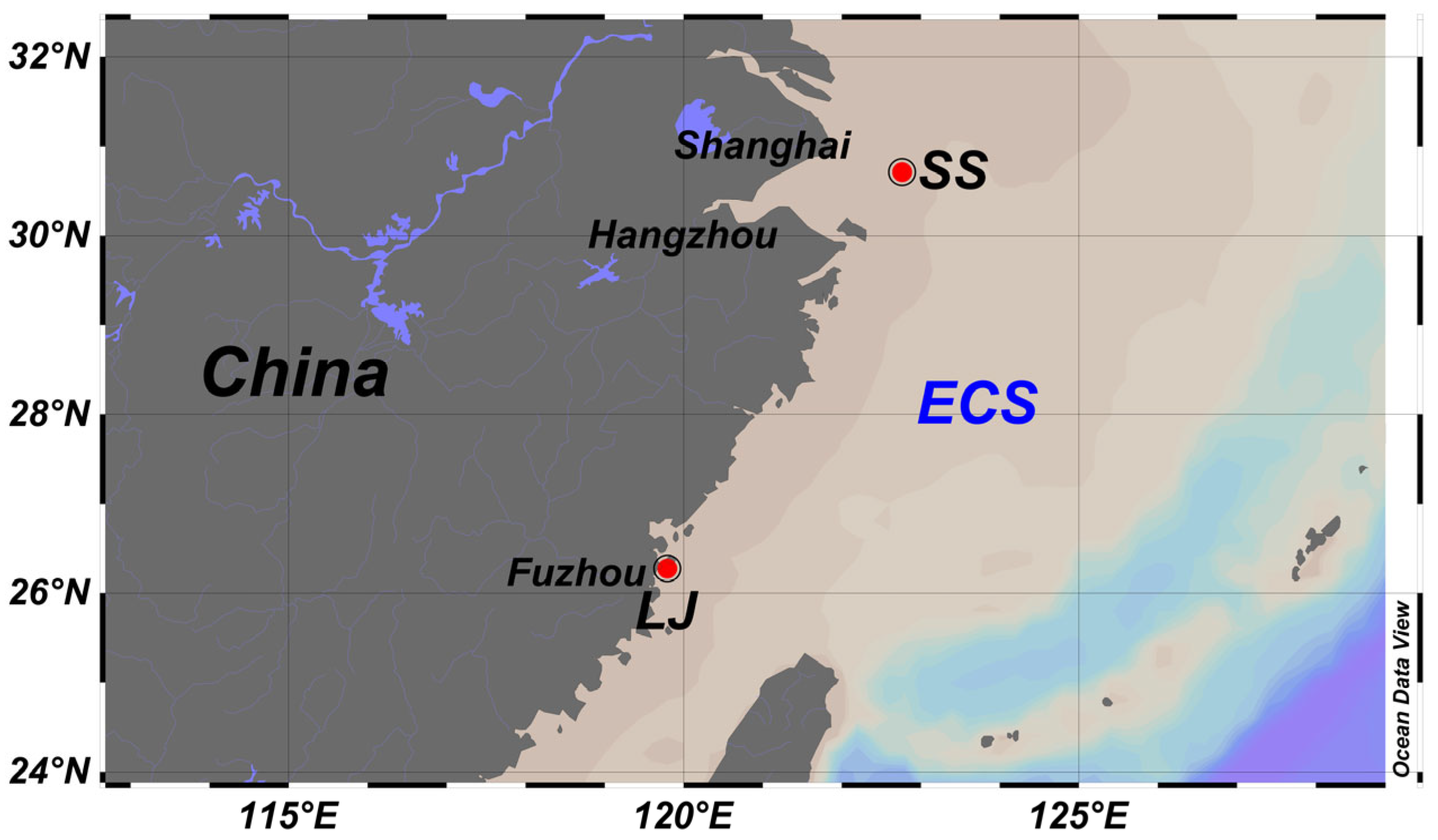

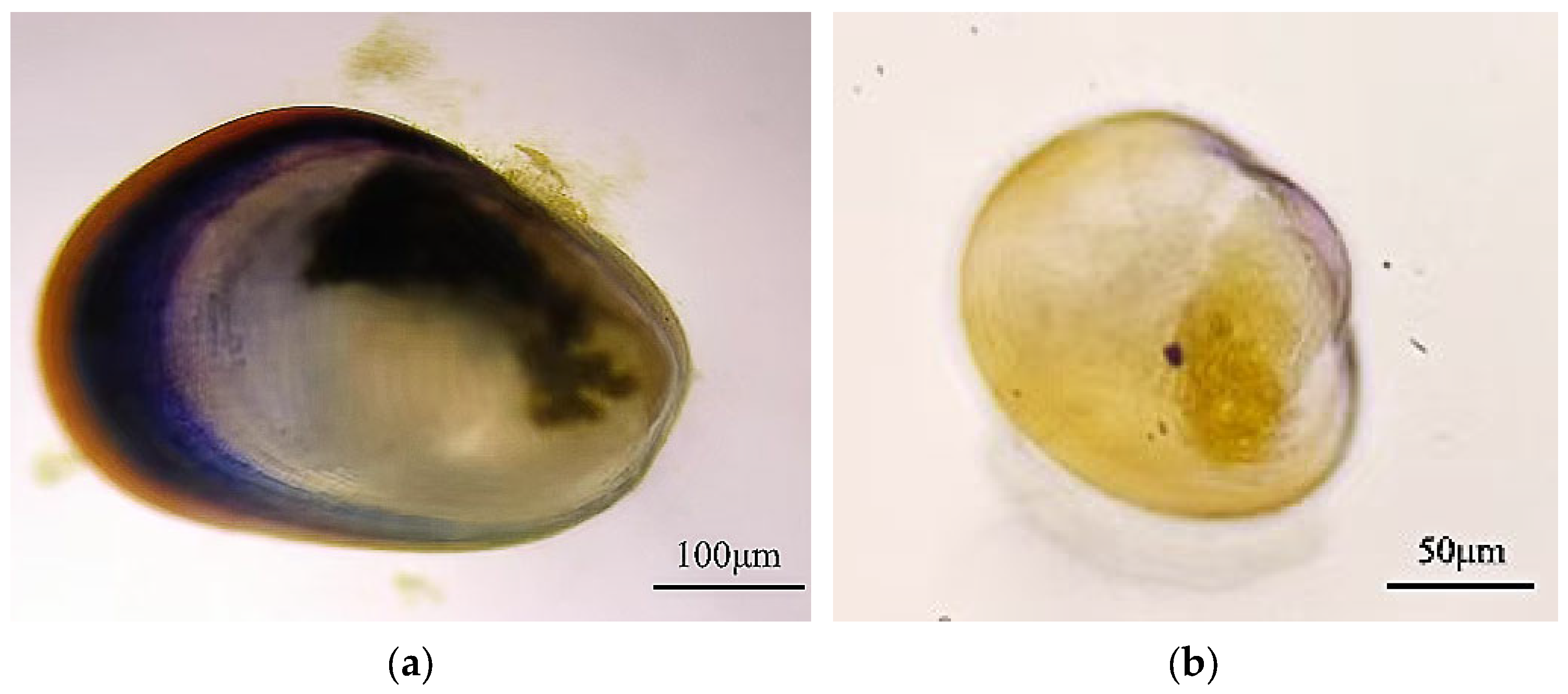

2.1. Preparation of Natural Biofilms, Juveniles and Larvae of M. coruscus

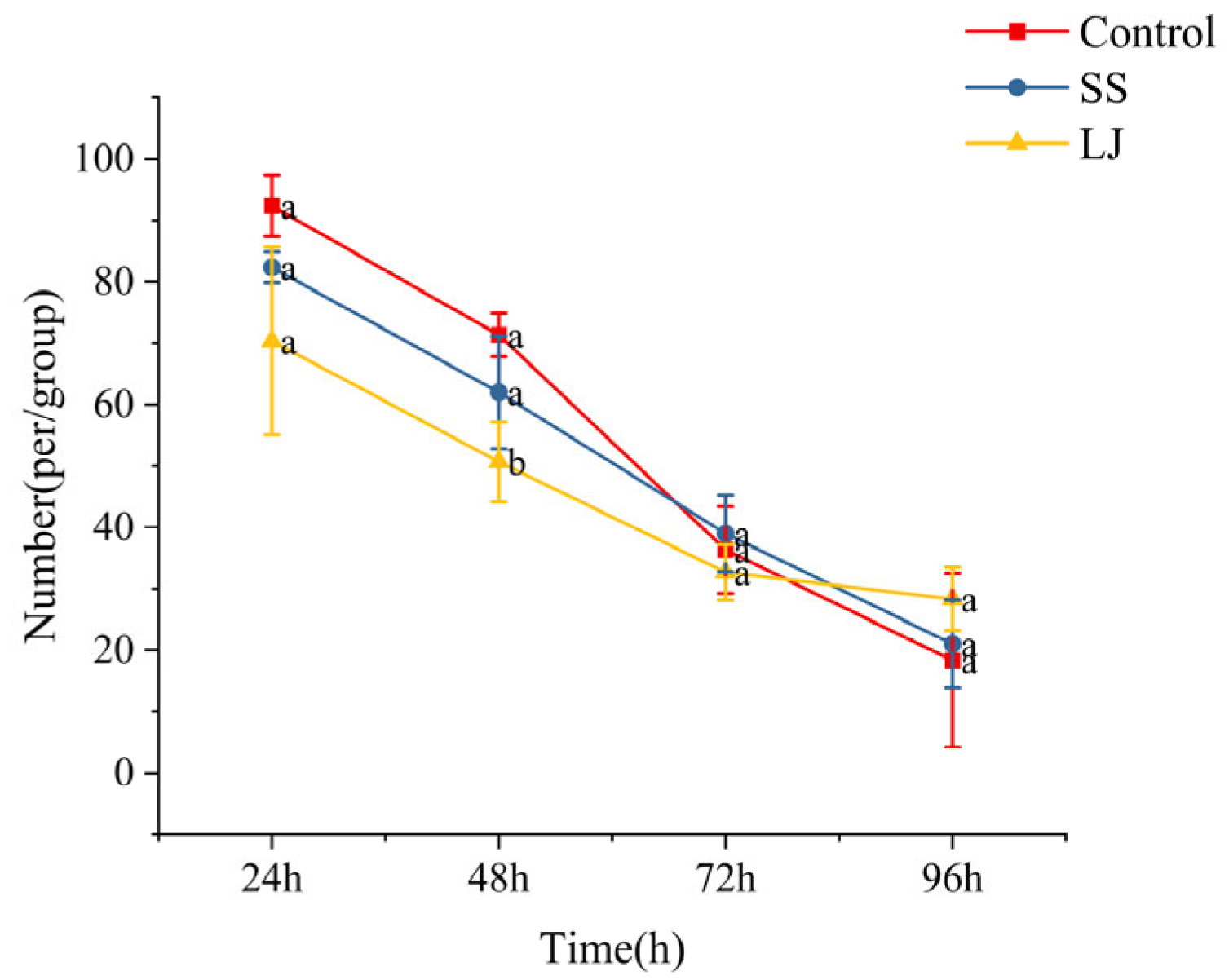

2.2. Natural Biofilm-Induced Settlement Assay for M. coruscus Juvenile

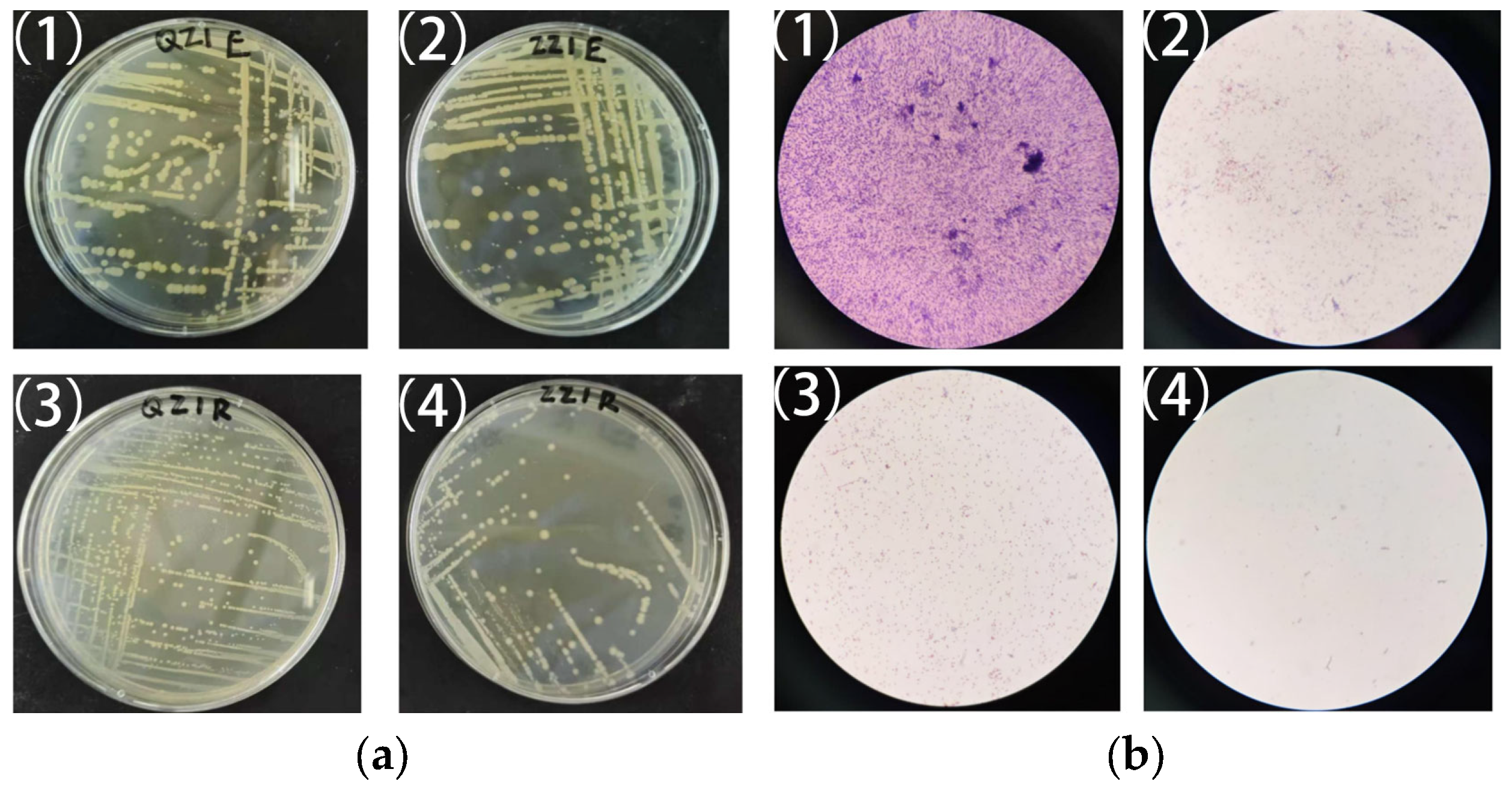

2.3. Isolation and Identification of Bacteria from Attached Juveniles

2.4. Larval Settlement Induced by Different Bacterial Biofilms

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

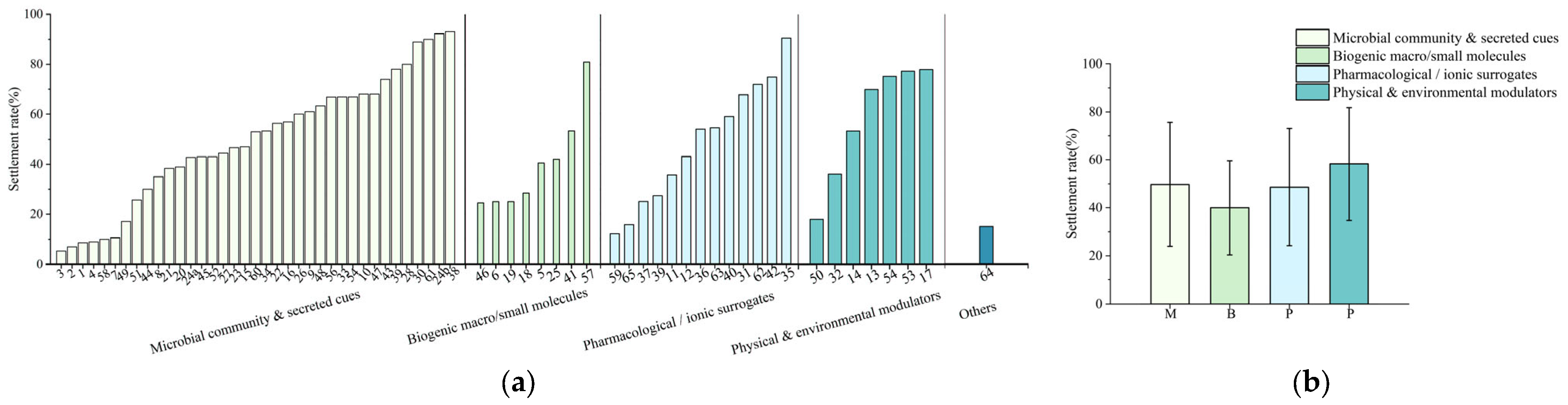

3.1. Analysis of M. coruscus Juvenile Settlement on Natural Microbial Biofilms

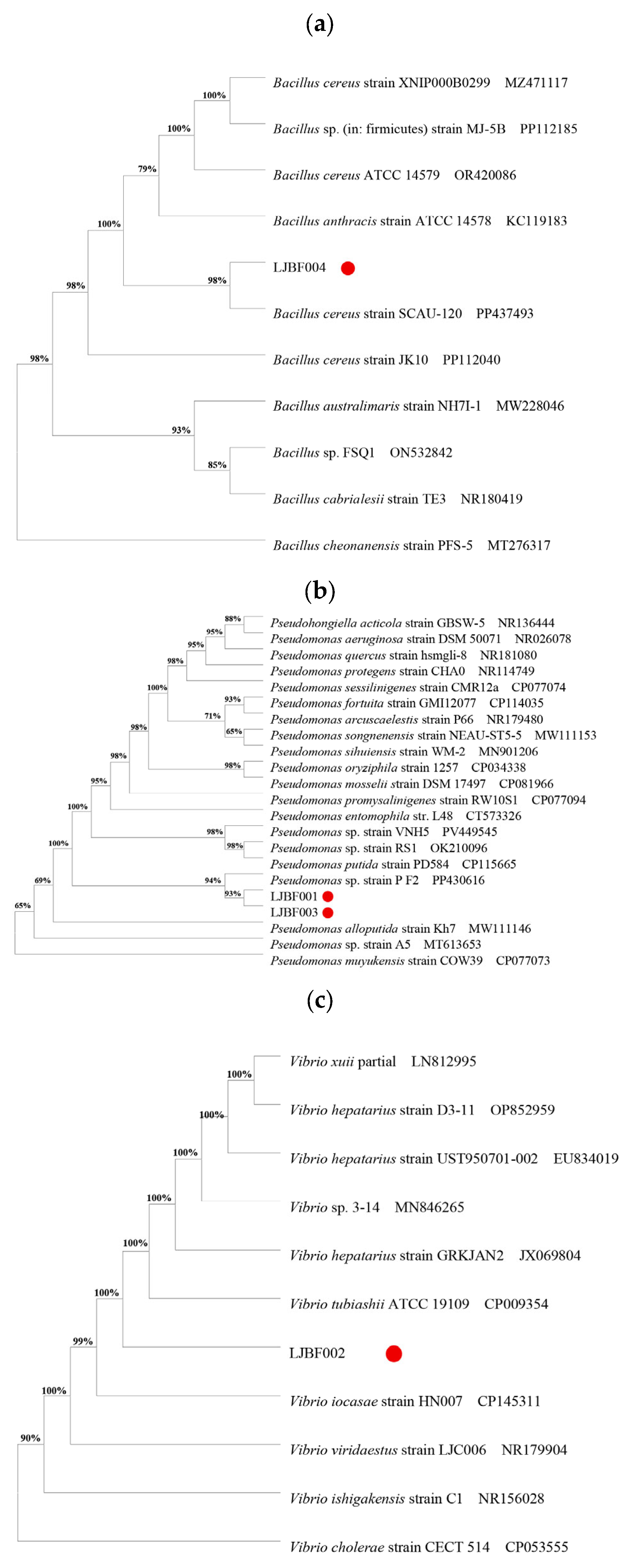

3.2. Bacterial Isolation and Identification

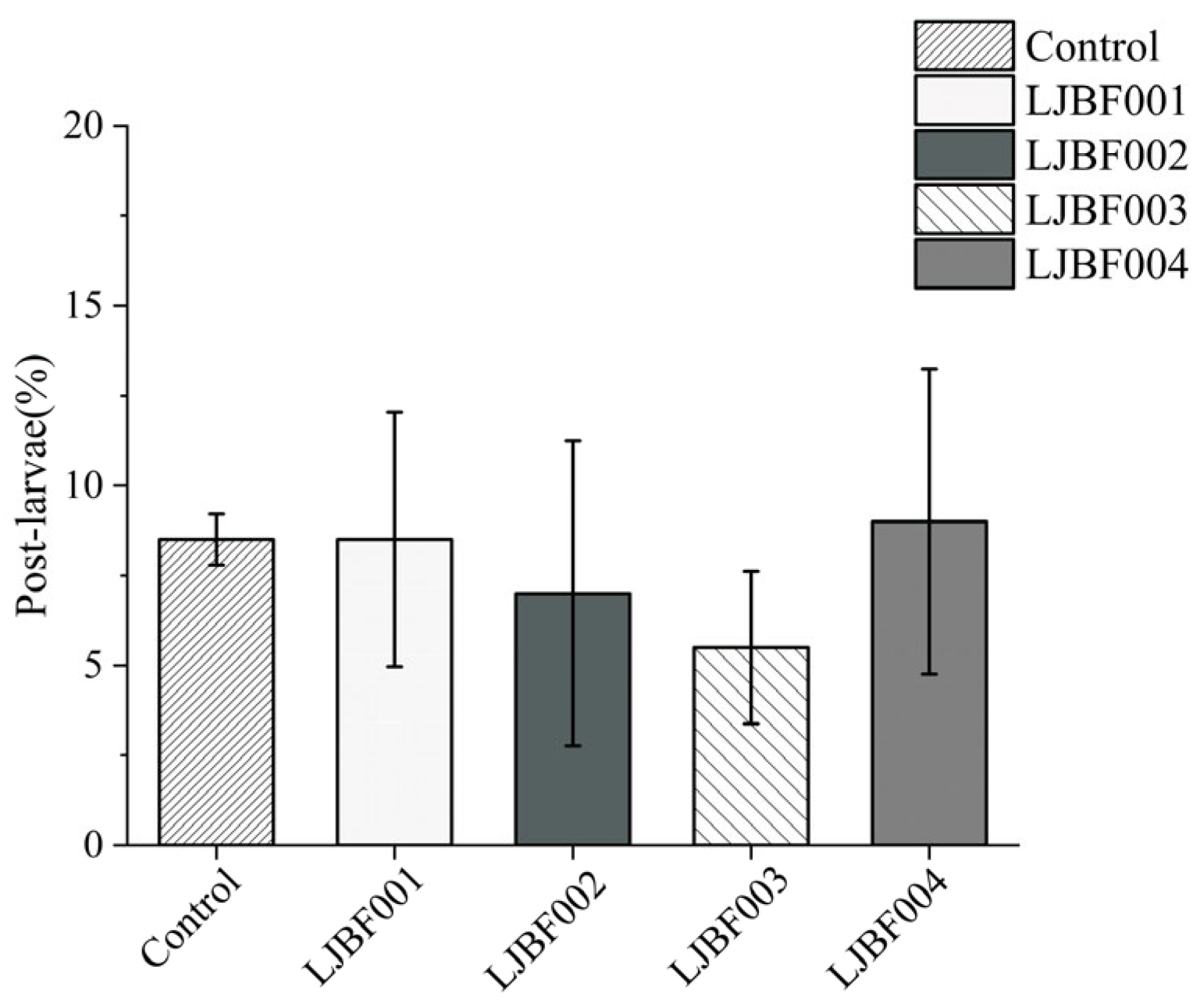

3.3. Dominant Bacteria Induce Metamorphic Development in M. coruscus Larvae

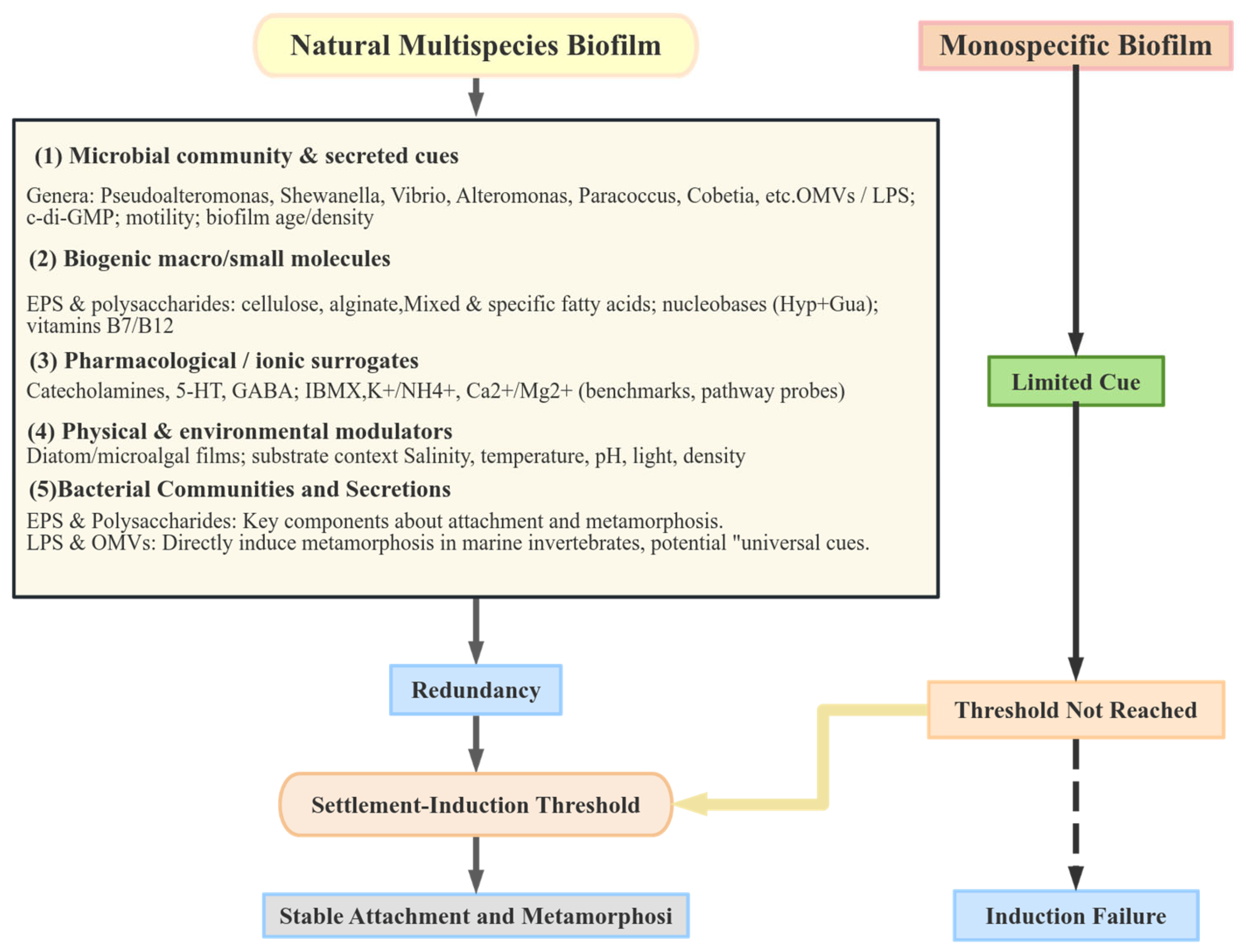

3.4. Mechanistic Conceptual Framework: Threshold–Multi-Cue Synergy

| No. | Species | Natural Metamorphosis Time | Attaches Post-Metamorphosis? | Inducing Factor | Inducing Environmental Parameters | Inducing Time | Inducing Success Rate | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | T | pH | DO | ||||||||

| 1 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Pseudomonas LJBF001 | 25 | 20 | 7.6 | - | 7 d | 8.6% | This study |

| 2 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Vibrio LJBF002 | 25 | 20 | 7.6 | - | 7 d | 7% | This study |

| 3 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Pseudomonas LJBF003 | 25 | 20 | 7.6 | - | 7 d | 5.3% | This study |

| 4 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Bacillus LJBF004 | 25 | 20 | 7.6 | - | 7 d | 9% | This study |

| 5 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Fatty acids (5 mg/L) | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 40.5% | [38] |

| 6 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Cellulose (2 mg/L) | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 25% | [39] |

| 7 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Pseudoalteromonas marina pilZ | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 10.56% | [40] |

| 8 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Virgibacillus sp.1 | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 35% | [41] |

| 9 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Paracoccus sp.1 | - | - | - | - | 24 h | 61% | [34] |

| 10 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Bacillus sp.2 | - | - | - | - | 12 h | 68% | [42] |

| 11 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Calcium, Pseudoalteromonas marina | - | - | - | - | 24 h | 35.56% | [43] |

| 12 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Adrenergic (10−4 mol/L) | - | - | - | - | 24 h | 43% | [44] |

| 13 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Middle wettability surfaces Cobetia sp.3 | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 70% | [45] |

| 14 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Light intensity, Water temperature and density | 13–23 | - | - | - | 12 h | 53.3% | [16] |

| 15 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Silanizing surfaces Staphylococcus sp.1 | - | - | - | - | 12 h | 47% | [46] |

| 16 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Vibrio cyclitrophicus | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 57% | [27] |

| 17 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Salinity, Temperature | 27.4–35.3 | 21–24 | 7.7–8.5 | - | 10 d | 78% | [47] |

| 18 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Vitamin B7 | - | - | 7.6 | - | 72 h | 28.33% | [48] |

| 19 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Cellulose | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 25% | [49] |

| 20 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Wild-type | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 38.89% | [28] |

| 21 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Pseudoalteromonas marina | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 38.33% | [50] |

| 22 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | OMV | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 56.42% | [51] |

| 23 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Shewanella marisflavi | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 46.67% | [52] |

| 24 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Bacillus sp.4 (larvae) | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 42.78% | [53] |

| Phaeobacter sp.1 (plantigrades) | 24 h | 92.22% | |||||||||

| 25 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Alginate | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 42% | [54] |

| 26 | Mytilus galloprovincialis | June–October | Y | Alteromonas sp. 1 | 28–32 | 22–26, 10–14 | 8.0–8.5 | - | 24 h | >60% | [29] |

| 27 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Pseudomonas sp. | 30 | 18 | 7.8 | - | 24 h | 44.44% | [55] |

| 28 | M. galloprovincialis | June–October | Y | Natural biofilm | - | 12–28 | - | - | 48 h | >80% | [12] |

| 29 | M. galloprovincialis | June–October | Y | 3 weeks old natural biofilm | - | 17 ± 1 | - | - | 48 h | 78% | [56] |

| 30 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Shewanella sp.1 | 30 | 18 | - | - | 48 h | 88.9% | [57] |

| 31 | Mytilopsis Sallei | - | Y | Hyp + Gua | 30 | 28 | - | - | 48 h | 67.8% | [58] |

| 32 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Temperature (22 °C) | - | 14–31 | - | - | 48 h | 36% | [59] |

| 33 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Vibrio sp.17 | - | 18 | - | - | 12 h | 67% | [60] |

| 34 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Pseudoalteromonas marina | 30 | 18 | - | - | 48 h | 53.3% | [61] |

| 35 | Oyster | - | Y | NH4Cl | - | - | 8.0 | - | <5 min | 90.6% | [62] |

| 36 | Pinctada Maxima | December–March | Y | Biofilm + Serotonin (10−3M) | - | - | - | - | 6 h | 54% | [63] |

| 37 | Pinctada Margaritifera | October–May | Y | GABA | - | - | - | - | 24 h | 25% | [64] |

| 38 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Natural biofilms of different ages | - | 18 | - | - | 48 h | 93% | [37] |

| 39 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | GABA (10−4 M) | - | 18 | - | - | 96 h | 27.2% | [35] |

| 40 | Mercenaria mercenaria | April–October | Y | Ca2+/Mg2+ | - | - | - | - | 24 h | 59.16% | [65] |

| 41 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | 10 mg/L LPS | 30 | 18 | - | - | 48 h | 53.3% | [66] |

| 42 | Mytilus Edulis | June–October | Y | IBMX (10−6–10−4 M) | 24 | 11 | - | - | 24 h | 75% | [67] |

| 43 | M. galloprovincialis | May–October | Y | Alteromonas sp.1 | - | 11 | - | - | 48 h | 74% | [13] |

| 44 | M.coruscus | May–October | Y | Pseudoalteromonas marina | - | 18 | - | - | 72 h | 30% | [30] |

| 45 | M.coruscus | May–October | Y | Ferric ions, Shewanella marisflavi ECSMB14101 biofilms | - | 18 | - | - | 96 h | 43% | [68] |

| 46 | Phragmatopoma califomica | May–October | Y | FFA | - | 20 | - | - | 24 h | 24.5% | [69] |

| 47 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Bacterial biofilms | 10, 20, 30 | 8, 18, 28 | - | - | 48 h | 68% | [70] |

| 48 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Bacterial biofilms | - | 18 | - | - | 48 h | 63.33% | [71] |

| 49 | Amusium pleuronectes | March–November | Y | Microalgae | 33 | 28 | - | - | 21 d | 17.21% | [31] |

| 50 | Pinctada maxima | October–May | Y | Density | 30.8–32.5 | 27.5–31.0 | 8.0–8.3 | - | - | 18% | [72] |

| 51 | P. maxima | October–May | Y | Bacterial biofilms | - | - | - | - | 48 h | 25.78% | [73] |

| 52 | Chlamys farreri | March–November | Y | Benthic diatom bacterial biofilms | - | 8—10 | - | - | 7 d | 43.02% | [32] |

| 53 | Perna viridis | October–May | Y | Salinity | 26–28 | 24.3–29.2 | 7.5–8.4 | - | 15 d | 77.32% | [33] |

| 54 | P. maxima | October–May | Y | Salinity (31.1) | 11.53–46.76 | - | - | - | 24 h | 75.36% | [74] |

| 55 | Haliotis discus hannai | March–November | Y | Benthic diatoms | 31.06 | 20 | - | - | 21 d | 67% | [75] |

| 56 | Styela canopus | March–November | Y | Photorhabdus | - | 25 | - | - | 48 h | 66.96% | [76] |

| 57 | M. coruscus | May–October | Y | Mytilus galloprovincialis peptide | 30 | 18 | - | - | 48 h | 81% | [77] |

| 58 | Serpula vermicularis, Bryozoa | March–November | Y | Bacterial biofilms | - | 28 | - | - | 1 h | 10% | [78] |

| 59 | S.vermicularis | March–November | Y | 10−4 IBMX | - | 28 | - | - | 48 h | 12% | [79] |

| 60 | Balanus amphitrite | March–November | Y | Navicula ramosissima | - | 25 | - | - | 24 h | 53% | [80] |

| 61 | Bryozoa | March–November | Y | Mixed bacterial and diatom biofilms | - | - | - | - | - | 90% | [81] |

| 62 | Argopecten irradians | May–October | Y | KCl | - | - | - | - | 12 h | 72% | [36] |

| 63 | Crassostrea nippona | October–May | Y | Epinephrine | 32–33 | 26–28 | - | - | 1 h | 54.55% | [82] |

| 64 | Scapharca subcrenata | March–November | Y | Polyethylene mesh sheet substrate | - | - | - | - | 24 h | 14.9% | [83] |

| 65 | Ostrea edulis (L.) | April–November | Y | GABA, Bacterial biofilms | - | 18 | - | - | 24 h | 15.7% | [84] |

3.5. Future Research Directions Inferred from the Comparative Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| SS | Shengsi Group |

| LJ | Lianjiang Group |

| ZMA 2216 | Zobell Marine Agar 2216 |

| NA | Nutrient Agar |

References

- Chang, R.-H.; Yang, L.-T.; Luo, M.; Fang, Y.; Peng, L.-H.; Wei, Y.; Fang, J.; Yang, J.-L.; Liang, X. Deep-Sea Bacteria Trigger Settlement and Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus Larvae. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L.; Li, S.H.; Bao, W.Y.; Yamada, H.; Kitamura, H. Effect of Different Ions on Larval Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquac. Res. 2015, 46, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L.; Li, X.; Liang, X.; Bao, W.Y.; Shen, H.D.; Li, J.-L. Effects of Natural Biofilms on Settlement of Plantigrades of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. Aquaculture 2014, 424–425, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Tan, L.; Yang, L.; Shi, G.; Wang, Z.; Liao, Z. Purification, cDNA Clone and Recombinant Expression of Foot Protein-3 from Mytilus coruscus. Protein Pept. Lett. 2011, 18, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Liao, Z.; Wang, X.; Bao, L.; Fan, M.; Li, X.; Wu, C.; Xia, S. Layer-by-Layer Proteomic Analysis of Mytilus galloprovincialis Shell. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Tang, Z.; Liu, S.; Liao, Z.; Xia, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Qi, P. Effects of Low Concentrations Copper on Antioxidant Responses, DNA Damage and Genotoxicity in Thick Shell Mussel Mytilus coruscus. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2018, 82, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Chen, K.; Li, Y.F.; Bao, W.Y.; Yoshida, A.; Osatomi, K.; Yang, J.-L. An A2-Adrenergic Receptor Is Involved in Larval Metamorphosis in the Mussel, Mytilus coruscus. Biofouling 2019, 35, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Y.L.; Zhu, X.; Yang, J.L.; Liang, X. Larval Metamorphosis Is Inhibited by Methimazole and Propylthiouracil That Reveals Possible Hormonal Action in the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.T.; Liang, L.L.; Liu, T.T.; Liang, X.; Yang, J.L. Effects of L-Arginine on Nitric Oxide Synthesis and Larval Metamorphosis of Mytilus coruscus. Genes 2023, 14, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Guo, X.P.; Yang, J.L.; Liang, X.; Bao, W.Y.; Shen, P.J.; Shi, Z.Y.; Li, J.L. Effects of Bacterial Biofilms on Settlement of Plantigrades of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. Aquaculture 2014, 433, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satuito, C.G.; Natoyama, K.; Yamazaki, M.; Fusetani, N. Inductin of Attachment and Metamorphosis of Laboratory Cultures Mussel Mytilus Edulis galloprovincialis Larvae by Microbial Film. Fish. Sci. 1995, 61, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.Y.; Satuito, C.G.; Yang, J.L.; Kitamura, H. Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis in Response to Biofilms. Mar. Biol. 2007, 150, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.Y.; Yang, J.L.; Satuito, C.G.; Kitamura, H. Larval Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis in Response to Alteromonas Sp. 1: Evidence for Two Chemical Cues? Mar. Biol. 2007, 152, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.M.; Zhang, J.; Ding, W.Y.; Liang, X.; Wan, R.; Dobretsov, S.; Yang, J.L. Reduction of Mussel Metamorphosis by Inactivation of the Bacterial Thioesterase Gene via Alteration of the Fatty Acid Composition. Biofouling 2021, 37, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Bao, W.; Guo, X.; Liang, X.; Shi, Z.; Li, J.; Ding, D. Effects of Substratum Type on Bacterial Community Structure in Biofilms in Relation to Settlement of Plantigrades of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 96, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.K.; Peng, L.H.; Gao, W.; Shen, H.D.; Liang, X.; Yang, J.L. Effects of Light Intensity, Water Temperature and Density on Aggregation of Juvenile mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2017, 32, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Qiu, C.; Yan, Y. Role of the South China Sea Summer Upwelling in Tropical Cyclone Intensity. Am. J. Clim. Change 2019, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, E.; Yang, S.; Wu, H.; Yang, C.; Li, C.; Liu, J.T. Kuroshio Subsurface Water Feeds the Wintertime Taiwan Warm Current on the Inner East China Sea Shelf. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 4790–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Deng, F.; Shumway, S.E.; Hu, M.; Wang, Y. The Thick-Shell Mussel Mytilus Coruscus: Ecology, Physiology, and Aquaculture. Aquaculture 2024, 580, 740350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Fu, Z.; Li, J.; Guo, B.; Ye, Y. Genetic Structure and Phylogeography of Commercial Mytilus unguiculatus in China Based on Mitochondrial COI and Cytb Sequences. Fishes 2023, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, R.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Gu, Z.; Mu, C.; Song, W.; Zhan, P.; Huang, J. Molecular Identification Reveals Hybrids of Mytilus coruscus × Mytilus galloprovincialis in Mussel Hatcheries of China. Aquacult. Int. 2020, 28, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, C.; Xu, M.; Guo, B. Genetic Analysis of Mussel (Mytilus coruscus) Populations on the Coast of East China Sea Revealed by ISSR-PCR Markers. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2012, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Yu, B.C.; Bi, Y.X.; Wang, W.D. The Biological Characteristics and Growth Patterns of Mytilus coruscus in the Waters of Zhongjieshan Islands. Chin. J. Ecol. 2015, 34, 471. [Google Scholar]

- Aljanabi, S.M.; Martinez, I. Universal and Rapid Salt-Extraction of High Quality Genomic DNA for PCR-Based Techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4692–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Xue, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xing, W.; Zhu, S.; Jiang, W.; Liu, J. Benzalkonium Chloride Disinfection Increases the Difficulty of Controlling Foodborne Pathogens Identified in Aquatic Product Processing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 488, 137140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, K. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Principle and Applications. In Synthetic Biology—New Interdisciplinary Science; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78984-090-2. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Liu, H.Y.; Yang, L.T.; Chang, R.H.; Peng, L.H.; Li, Y.F.; Yang, J.L. Effects of Dynamic Succession of Vibrio Biofilms on Settlement of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Fish. China 2020, 44, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L.; Mu, J.Y.; Hu, X.M.; Zhu, Y.T.; Peng, L.H.; Liang, X. Effects of Bacterial Motility on Dynamic Succession of Biofilms and Settlement of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. Prog. Fish. Sci. 2023, 44, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.Y.; Satuito, C.G.; Kitamura, H. Larval Settlement Mechanism of the Mussel Mytilus Galloprovincialis. Sess. Org. 2008, 25, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.M.; Peng, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, G.; Liang, X.; Yang, J.L. Bacterial C-Di-GMP Signaling Gene Affects Mussel Larval Metamorphosis through Outer Membrane Vesicles and Lipopolysaccharides. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.Q.; Li, Y.N.; Ma, Z.H.; Yu, G.; Deng, Z.H.; Wu, K.C. Effects of Alone and Combined Microalgae and Marine Yeasts on Growth and Survival of Larval Long Rib Solar Moon Shell Amusium pleuronectes. Fish. Sci. 2018, 37, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.R.; Fang, J.G.; Mao, Y.Z.; Li, F.; Gao, Y.P.; Fang, J.H.; Wang, T.Y.; Jiang, Z.J. Effect of Benthic Diatom Filmed Substrate on Settlement and Metamorphosis of Scallop. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2020, 51, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, G.F.; Yang, F.; Chi, J.X.; Liang, J.; Liu, Z.; Huo, Z.M.; Sang, S.T.; Han, H.; Y, X.W. The Influence of Salinity on Hatching, Growth and Survival of Larvae and Juveniles in Green Mussel Perna viridis. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2013, 28, 549–552. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N.; Yang, J.L.; Shen, H.D.; Peng, L.H.; Liang, X. Effects of gut bacteria on the settlement of spats of Mytilus coruscus. Mar. Sci. 2017, 41, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, J. Effects of GABA Receptor Antagonists Bicuculline and CGP52432 on Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of the Mussel (Mytilus coruscus). J. Fish. China 2022, 46, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.H.; Dong, Q.H.; Wang, Z.P.; Tian, C.Y.; Wang, R.C. A Study on Adhering Metamorphosis in Eyebot Larvae of Bay Scallop Argopecten irradians by KCL of Different Concentrations. Trans. Oceanol. Limnol. 2001, 4, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Bao, W.Y.; Gu, Z.Q.; Li, Y.F.; Liang, X.; Ling, Y.; Cai, S.L.; Shen, H.D.; Yang, J.L. Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus in Response to Natural Biofilms. Biofouling 2012, 28, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.H.; Li, X.; Liang, X.; Yang, J.L. Effects of Three Fatty Acids on Biofilm Formation and Settlement and Metamorphosis of Hard Shelled Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2021, 36, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, A.Q.; Li, J.Z.; Zhang, J.B.; Liang, X.; Wan, R.; Yang, J.L. Effect of Cellulose on Pseudoalteromonas Marina Biofilm Biological Characteristics and Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of Mytilus coruscus. J. Fish. China 2023, 47, 089611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.S.; Yang, J.L.; Zhang, J.B.; Wan, R.; Liang, X. Knockout of Pseudoalteromonas Marina pilZ Gene Inhibited the Settlement and Metamorphosis of Mytilus coruscus. Acta Oecologica Sin. 2022, 44, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yang, J.; Fang, J.; Peng, L.; Wei, Y.L.; Yang, L. Effects of Biofilms of Deep-Sea Bacteria under Varying Temperatures on Larval Metamorphosis of Mytilus Coruscus. J. Fish. China 2020, 44, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, Y.R.; Guo, X.P.; Li, J.L.; Yang, J.L. Effects of Bacterial Biofilms Formed on Low Surface Wettability on Settlement of Plantigrades of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2015, 30, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.H.; Xu, K.H.; Liang, X.; Yang, J.L.; Cai, Y.S. Effects of Calcium on Biofilm Formation of the Bacterium Pseudoalteromonas Marina and Settlement of Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2020, 35, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L.; Chen, Y.R.; Guo, X.P.; Lin, Y.F.; Xuan, H.C.; Li, J.L. Effects of Cholinoceptor Compounds on Larval Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Fish. China 2014, 12, 2012–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.L.; Guo, X.P.; Chen, Y.R.; Shen, H.D.; Ding, D.W. Effects of Bacterial Biofilms Formed on Middle Wettability Surfaces on Settlement of Plantigrades of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Fish. China 2015, 3, 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, X. Effects of Marinebacteria from Silanizing Surfaces on Plantigrade Settlement of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Fish. China 2015, 39, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.H.; Wang, Y.H.; Ke, A.Y.; Chen, X.X. Effect of ecological factors on growth and survival rate of thick shell mussel (Mytilus coruscus Gloud) eyebot larval. J. Aquac. 2015, 36, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.L.; Duan, Z.H.; Ding, W.Y.; Xu, J.K.; Gu, Z.Q.; Liang, X. Effects of VB7 and VB12 on Biofilm Formation and Larval Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. Prog. Fish. Sci. 2021, 42, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.H.; Zhen, X.; Li, X.; Liang, X.; Yang, J.L. Regulation of Formation of Biofilms and Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of Mussel Mytilus coruscus by Cellulose. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2020, 35, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.H.; Liang, X.; Xu, J.K.; Dobretsov, S.; Yang, J.L. Monospecific Biofilms of Pseudoalteromonas Promote Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of Mytilus coruscus. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.J.; Miao, T.Y.; Hu, X.M.; Zhang, W.; Yang, J.L. Effects of Exogenous Addition of Outer Membrane Vesicles on Biofilm Formation of Pseudoalteromonas Marina and Settlement of Mussel (Mytilus coruscus). J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2024, 38, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Jinong, Y.; Ju, L.; Xiaoyu, W.; Jingyi, X. Effect of the content of colanic acid in marine bacterial biofilms on the settlement of Mytilus coruscus plantigrades. Acta Oecologica Sin. 2023, 45, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.K.; Wang, J.S.; Fang, Y.H. Effects of Intestinal Bacterial Biofilms on Settlement Process of Larvae and Plantigrades in Mytilus coruscus. Acta Oecologica Sin. 2021, 43, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yang, J.L.; Zhu, Y.T.; He, C.H.; He, K.; Chen, H.E. Effects of Alginate on Biofilm Formation of Pseudoalteromonas Marina and Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2022, 37, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.M.; Peng, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, F.; Tao, Y.; Liang, X.; Yang, J.L. Bacterial C-Di-GMP Triggers Metamorphosis of Mussel Larvae through a STING Receptor. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toupoint, N.; Mohit, V.; Linossier, I.; Bourgougnon, N.; Myrand, B.; Olivier, F.; Lovejoy, C.; Tremblay, R. Effect of Biofilm Age on Settlement of Mytilus Edulis. Biofouling 2012, 28, 985–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L.; Shen, P.J.; Liang, X.; Li, Y.F.; Bao, W.-Y.; Li, J.L. Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus in Response to Monospecific Bacterial Biofilms. Biofouling 2013, 29, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Dai, Q.; Qi, Y.; Su, P.; Huang, M.; Ke, C.; Feng, D. Bacterial Nucleobases Synergistically Induce Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis in the Invasive Mussel Mytilopsis sallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01039-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; TAO, Y.; Yiang, J.L.; Liang, X. Effects of Ocean Warming on Bacterial Biofilm Formation and Biofilm-Induced Larval Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2025, 40, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Huang, D.F.; Peng, L.H.; Guo, X.P.; Zhang, D.M.; Yang, J.L. Effects of Vibrio Biofilms of Different Sources on Settlement of Plantigrades of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Fish. China 2017, 41, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.R.; Liang, X.; Wang, Y.Y.; He, Z.P.; Yang, J.L. Characterization and Role in Settlement of Mussel Mytilus Coruscus of Eight Hadal Bacterial Biofilms. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2025, 39, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coon, S.L.; Walch, M.; Fitt, W.K.; Weiner, R.M.; Bonar, D.B. Ammonia Induces Settlement Behavior in Oyster Larvae. Biol. Bull. 1990, 179, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, S.; Qian, P.Y. Larval Settlement of the Silver- or Goldlip Pearl Oyster Pinctada maxima (Jameson) in Response to Natural Biofilms and Chemical Cues. Aquaculture 2003, 220, 883–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroudi, M.S.; Southgate, P.C. The Effect of Chemical Cues on Settlement Behaviour of Blacklip Pearl Oyster (Pinctada margaritifera) Larvae. Aquaculture 2002, 209, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Shi, B.; Li, Y.; Liang, S.; Liu, H.; Dai, W.; Guo, Y. Induction of Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of Mercenaria mercenaria Using Excess Ca2+ and Mg2+ alone or in Combination. Aquac. Rep. 2025, 40, 102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.X.; Li, J.Z. Effects of lipopolysaccharide on biofilm formation and larval metamorphosis of the mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Fish. China 2022, 46, 2134–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobretsov, S.V.; Qian, P.-Y. Pharmacological Induction of Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis in the Blue Mussel Mytilus edulis L. Biofouling 2003, 19, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Ma, F. Effects of ferric ions on the capacity of Shewanella marisflavi ECSMB14101 biofilms to induce the settlement and metamorphosis of Mytilus coruscus. J. Shanghai Ocean Univ. 2025, 34, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, J.R.; Faulkner, D.J. Specific Free Fatty Acids Induce Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of the Reef-Building Tube Worm Phragmatopoma califomica (Fewkes). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1986, 102, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Guo, X.P.; Xu, J.K.; Peng, L.H.; Chen, H.D.; Yang, J.L.; Liang, X. Effects of Environmental Factors on Formation of Bacterial Biofilms and Settlement of Plantigrades of Mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2017, 32, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; He, C.H.; Yu, X.B.; Yang, J.L. The Effect of Mono-Species Bacterial Biofilms Formed on the Surface of Artificial Reef on Settlement of Plantigrades in Mytilus coruscus. Prog. Fish. Sci. 2024, 45, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.L.; Xie, S.H.; Deng, Y.W.; Wang, Q.G. Effects of Stocking Density on Hatching, Growth, Survival and Metamorphosis at Larval Stages of Pearl Oyster Pinctada maxima. Trans. Oceanol. Limnol. 2017, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, T.; Aimin, W.; Yaohua, S.; Zhifeng, G.; Ling, H.; Weiwei, D. Culture of Biofilm and Its Influence on Settlement of Pinctada maxima Larvae. Genom. Appl. Biol. 2016, 35, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.Z.; Zhou, Y.H.; Liang, X.X.; Huang, H.L.; Chu, Q.Z. Effects of sea salinity on the growth and survival of Pinctada margaritifera granosa Larvae and juveniles. J. Guandong Ocean. Univ. 2013, 33, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Tian, X.L. Effects of Species Composition of Benthic Diatoms on Growth and Survival of Postlarval and Juvenile Abalone Haliotis discus hannai. Fish. Sci. 2011, 30, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Lu, J.Y.; Zhou, S.Q.; Huang, Y.; Feng, D.Q.; Ke, C.H. Influences of marine adhesive bacteria on settlement and metamorphosis of Styela conopus Savigny larvae. Acta Oecologica Sin. 2005, 27, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.Z.; Yang, J.L.; Liang, X.; Lin, Q.; He, C.H. Effects of Mytilus Galloprovincialis Peptide on Settlement Ofmussel Juveniles Induced by Bacterial Biofilms. J. Fish. China 2024, 48, 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Dobretsov, S.; Dahms, H.; Yili, H.; Wahl, M.; Qian, P.Y. The Effect of Quorum-Sensing Blockers on the Formation of Marine Microbial Communities and Larval Attachment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 60, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Xiao, X.; Qian, P.-Y. Inhibitory Effects of a Branched-Chain Fatty Acid on Larval Settlement of the Polychaete Hydroides Elegans. Mar. Biotechnol. 2009, 11, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouuchi, T.; Satuito, C.G.; Kitamura, H. Sugar Compound Products of the Periphytic Diatom Navicula ramosissima Induce Larval Settlement in the Barnacle, Amphibalanus Amphitrite. Mar. Biol. 2007, 152, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahms, H.; Dobretsov, S.; Qian, P.Y. The Effect of Bacterial and Diatom Biofilms on the Settlement of the Bryozoan Bugula Neritina. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2004, 313, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Q. The induction of metamorphosis in Iwagaki oyster (Crassostrea nippona). J. Fish. China 2018, 42, 1729–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.L.; Li, Q.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Kong, L.F.; Qiu, Z.X.; Li, L. The Effect of Different Substrates on Bloody Clams (Scapharca subcrenata) Larvae Settlement and Metamorphosis. Mar. Sci. 2013, 37, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mesías Gansbiller, C.; Silva, A.; Maneiro, V.; Pazos, A.; Sánchez, J.L.; Pérez-Parallé, M.L. Effects of Chemical Cues on Larval Settlement of the Flat Oyster (Ostrea edulis L.): A Hatchery Approach. Aquaculture 2013, 376–379, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, W.B.; Coleman, D.C.; Wiebe, W.J. Prokaryotes: The Unseen Majority. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6578–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, F.; Malfatti, F. Microbial Structuring of Marine Ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlan, R.M. Biofilms: Microbial Life on Surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingender, J.; Neu, T.R.; Flemming, H.-C. (Eds.) Microbial Extracellular Polymeric Substances; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; ISBN 978-3-642-64277-7. [Google Scholar]

- Costerton, J.W.; Cheng, K.J.; Geesey, G.G.; Ladd, T.I.; Nickel, J.C.; Dasgupta, M.; Marrie, T.J. Bacterial Biofilms in Nature and Disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1987, 41, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, M.E.; O’toole, G.A. Microbial Biofilms: From Ecology to Molecular Genetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR 2000, 64, 847–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoodley, P.; Sauer, K.; Davies, D.G.; Costerton, J.W. Biofilms as Complex Differentiated Communities. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2002, 56, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W.; Lewandowski, Z.; Caldwell, D.E.; Korber, D.R.; Lappin-Scott, H.M. Microbial Biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1995, 49, 711–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, G.; Sunagawa, S. Marine Microbial Diversity. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R489–R494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.; Besemer, K.; Burns, N.R.; Battin, T.J.; Bengtsson, M.M. Light Availability Affects Stream Biofilm Bacterial Community Composition and Function, but Not Diversity. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 5036–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardón, M.; Pringle, C.M. The Quality of Organic Matter Mediates the Response of Heterotrophic Biofilms to Phosphorus Enrichment of the Water Column and Substratum. Freshw. Biol. 2007, 52, 1762–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battin, T.J.; Kaplan, L.A.; Denis Newbold, J.; Hansen, C.M.E. Contributions of Microbial Biofilms to Ecosystem Processes in Stream Mesocosms. Nature 2003, 426, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zobell, C.E.; Allen, E.C. The Significance of Marine Bacteria in the Fouling of Submerged Surfaces. J. Bacteriol. 1935, 29, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Hadfield, M.G. Composition and Density of Bacterial Biofilms Determine Larval Settlement of the Polychaete Hydroides Elegans. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003, 260, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, S.A.K.A.; Li, J.-Y.; Kitamura, H. Larval Metamorphosis of the Sea Urchins, Pseudocentrotus Depressus and Anthocidaris Crassispina in Response to Microbial Films. Mar. Biol. 2004, 144, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggett, M.J.; Williamson, J.E.; de Nys, R.; Kjelleberg, S.; Steinberg, P.D. Larval Settlement of the Common Australian Sea Urchin Heliocidaris Erythrogramma in Response to Bacteria from the Surface of Coralline Algae. Oecologia 2006, 149, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, M.G. Biofilms and Marine Invertebrate Larvae: What Bacteria Produce That Larvae Use to Choose Settlement Sites. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2011, 3, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, N.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Du, J.; Liu, W.; Liang, X.; Ye, Y.; Li, J. Settlement Induction in Mytilus coruscus Is Driven by Cue Diversity: Evidence from Natural Biofilms and Bacterial Isolates. Water 2025, 17, 3395. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233395

Chen N, Fu Y, Zhang Q, Du J, Liu W, Liang X, Ye Y, Li J. Settlement Induction in Mytilus coruscus Is Driven by Cue Diversity: Evidence from Natural Biofilms and Bacterial Isolates. Water. 2025; 17(23):3395. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233395

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ni, Yonghui Fu, Qianyu Zhang, Jie Du, Wanting Liu, Xinjie Liang, Yingying Ye, and Jiji Li. 2025. "Settlement Induction in Mytilus coruscus Is Driven by Cue Diversity: Evidence from Natural Biofilms and Bacterial Isolates" Water 17, no. 23: 3395. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233395

APA StyleChen, N., Fu, Y., Zhang, Q., Du, J., Liu, W., Liang, X., Ye, Y., & Li, J. (2025). Settlement Induction in Mytilus coruscus Is Driven by Cue Diversity: Evidence from Natural Biofilms and Bacterial Isolates. Water, 17(23), 3395. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233395