Microplastic Removal by Flotation: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Research Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

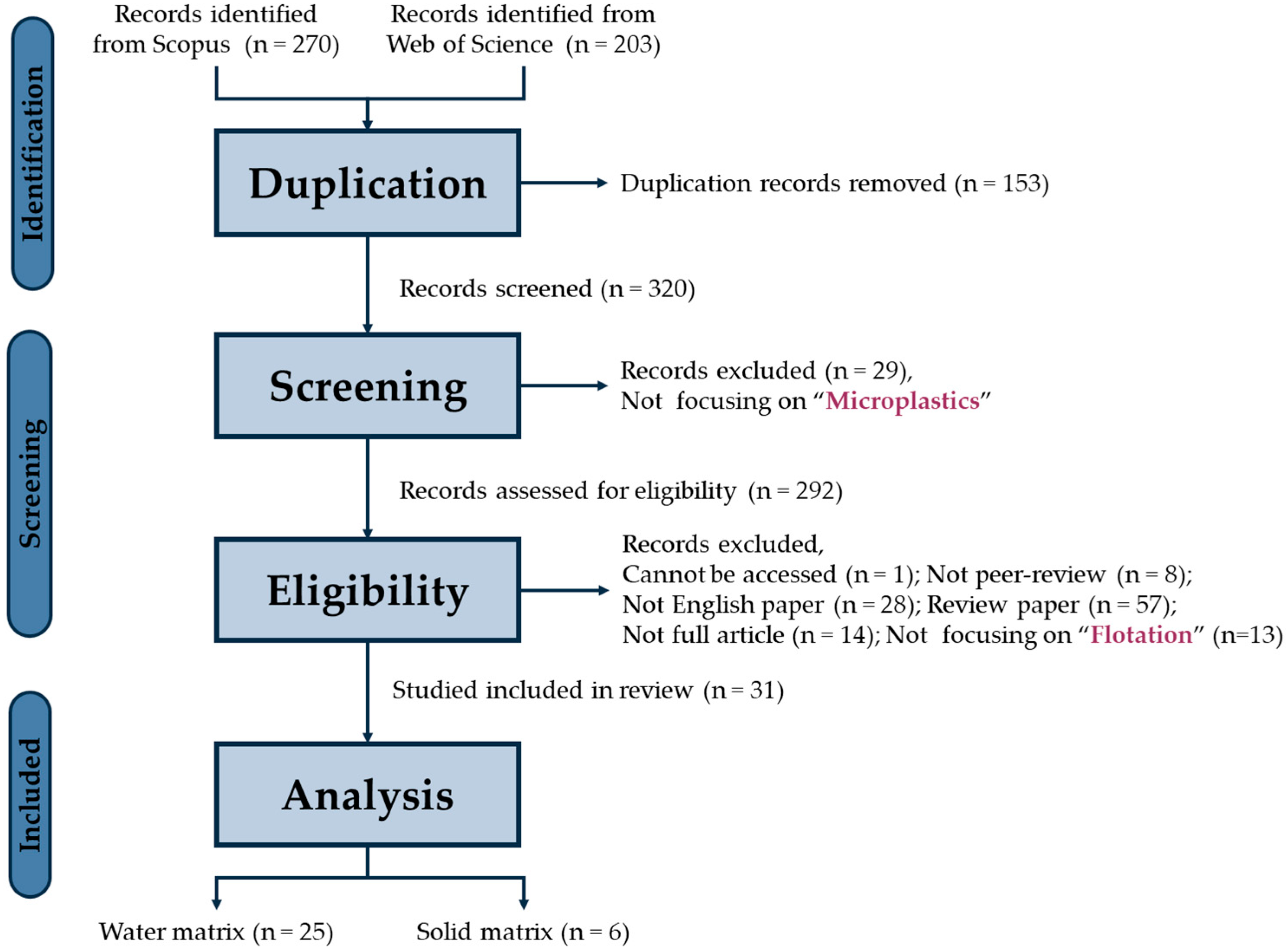

2. Methodology

2.1. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

2.2. Bibliometrics Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Review Results

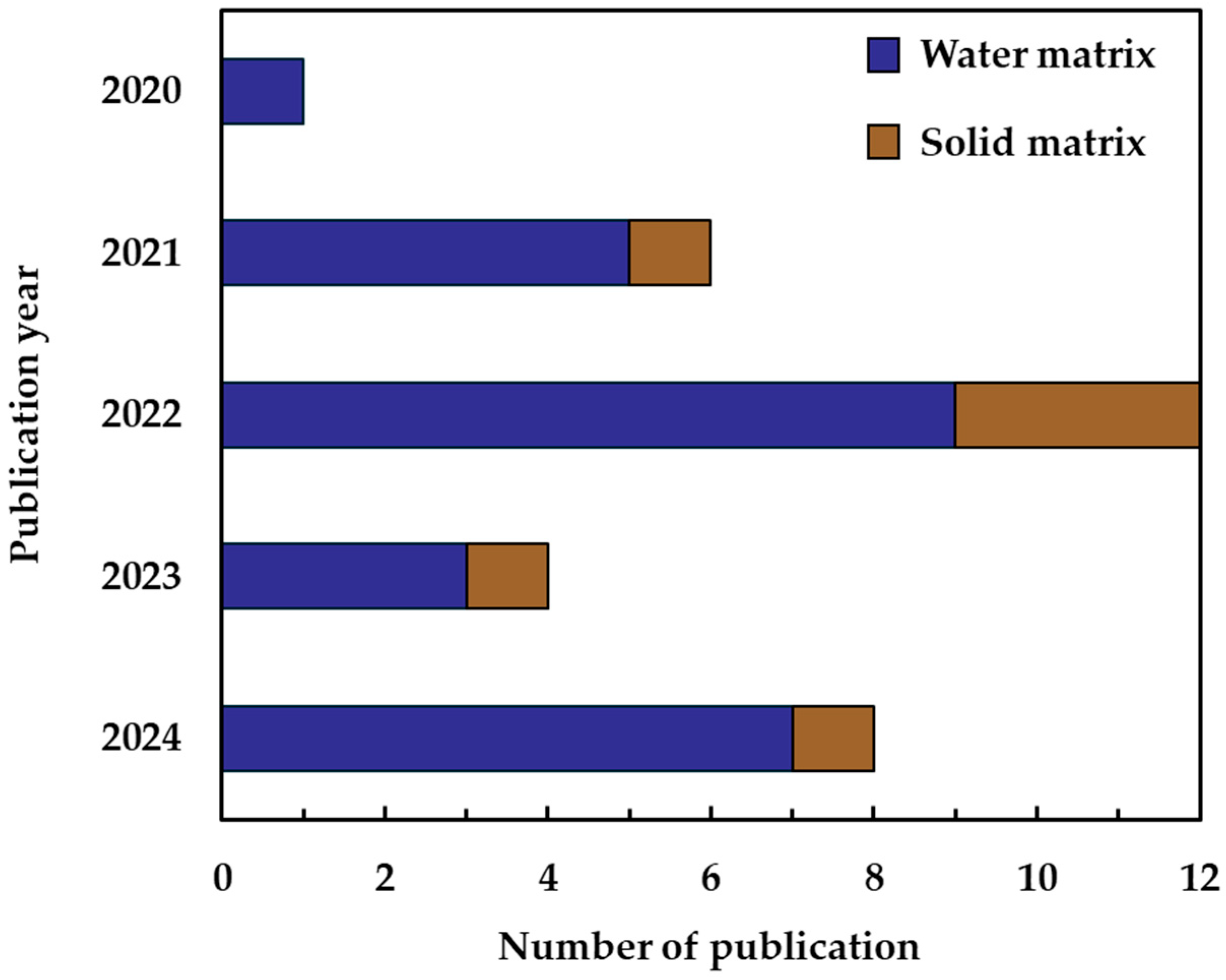

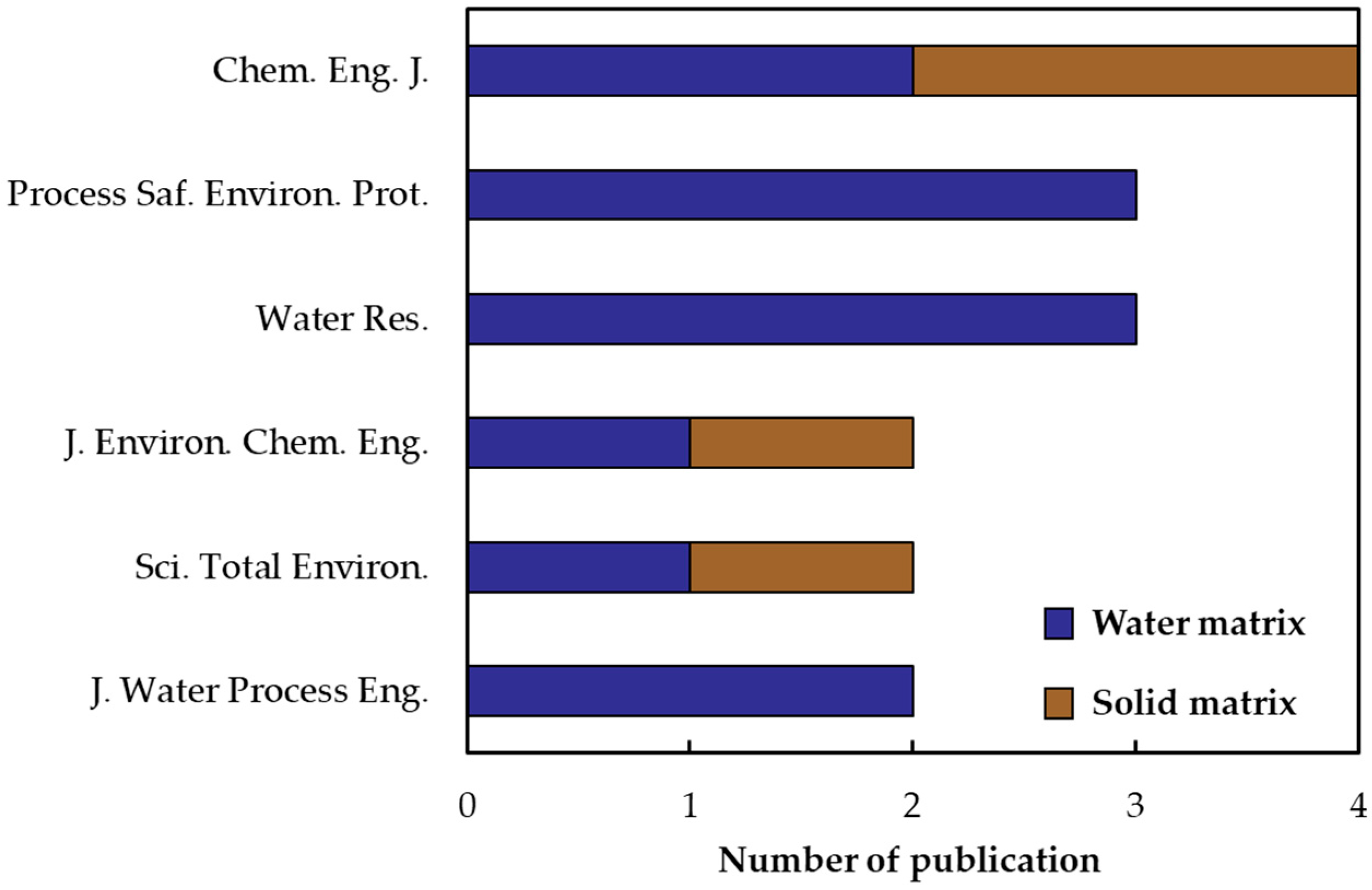

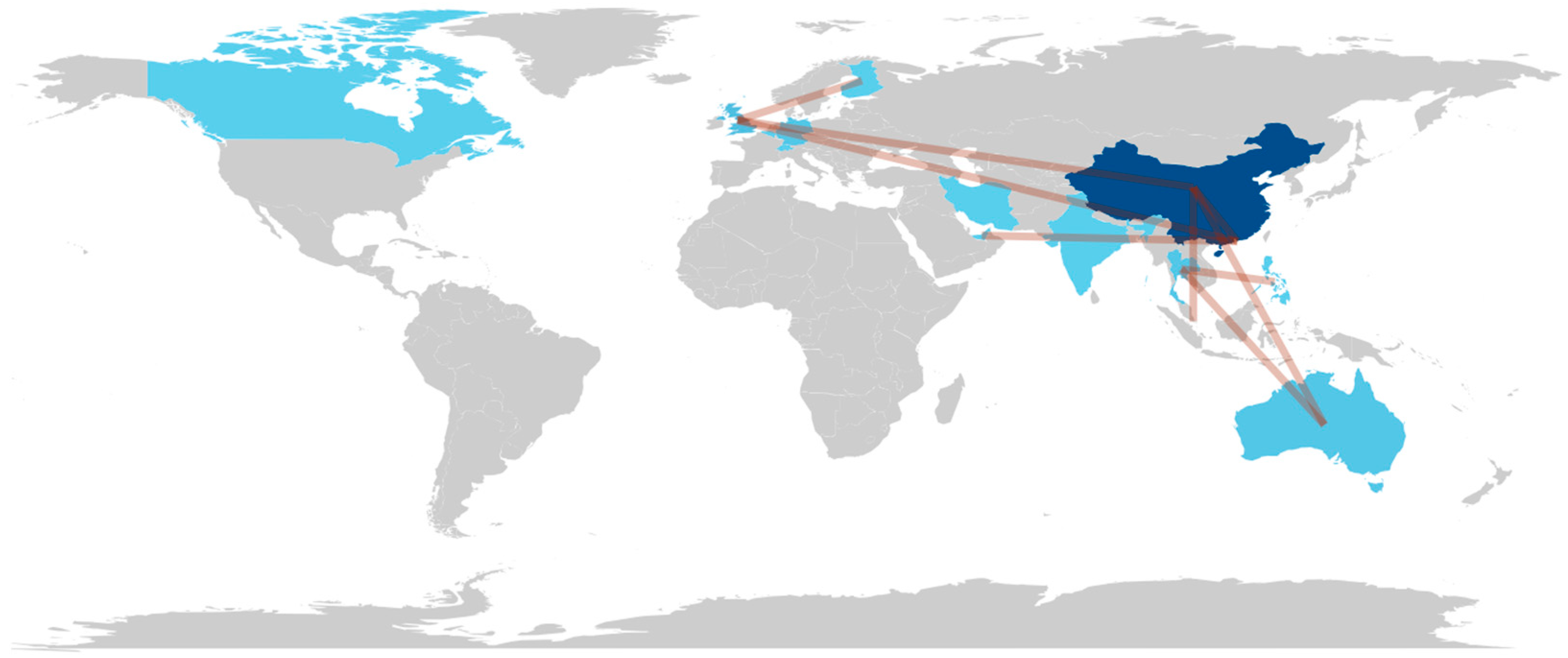

3.2. Bibliometric Results

3.3. Meta-Analysis Results

3.3.1. Removal of Microplastics from Water Using Flotation

| Size [µm] | Polymer Types | Flotation Techniques | Assisted Techniques | Chemicals Used | Removal Efficiency [%] | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | PE | PS | PET | PVC | Others | ||||||

| <5000 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | CGA | SMSN | 99.0 | [47] | ||

| <5000 | √ | √ | Flotation | – | Terpineol | 98.2 | [50] | ||||

| 50–5000 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | – | Vegetable oil | ≥98.0 | [51] |

| 2000–3000 | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | Hydrophilization | α-Terpineol | 99.8 | [40] | |||

| 500–1000 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | – | NaOL and DTAC | 100 | [52] | ||

| 100–1000 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | Agglomeration | Kerosene | 96.0–99.0 | [49] |

| 100–500 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | TEOS sol–gel | TEOS | 95.0–100.0 | [54] |

| 40–100 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | TEOS sol–gel | TEOS | 82.0–98.0 | [54] |

| <105 | √ | Flotation | Hydrocyclone | – | 26.0 | [44] | |||||

| 10–100.79 | – | Flotation | Hydrocyclone | – | 90.0 | [55] | |||||

| – | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | Gel coagulation–spontaneous | PAC and PAFC | 93.0–99.0 | [53] | |||

| – | √ | √ | Flotation | – | – | 100.0 | [42] | ||||

| <106 | √ | √ | √ | DAF | Positive modification | CTAB and PDAC | 48.7 | [45] | |||

| 10–600 | √ | √ | √ | √ | MB flotation | – | – | 83.3 | [56] | ||

| 1–50 | √ | √ | √ | MNBs flotation | – | – | ~92.6 | [57] | |||

| <10 | – | MNBs flotation | – | – | 36.0 | [58] | |||||

| <1000 | √ | √ | √ | Carrier flotation | Ionized air | – | >90.0 | [59] | |||

| 300 | √ | Foam Flotation | – | Carbonate-modified nonionic surfactants | 40.0 | [60] | |||||

| Size [µm] | Polymer Types | Flotation Techniques | Assisted Techniques | Chemicals Used | Removal Efficiency [%] | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | PE | PS | PET | PVC | Others | ||||||

| <5000 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | CGA | SMSN | 89.0 | [47] | ||

| 2000–3000 | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | Hydrophilization | K2FeO4 | 100.0 | [62] | |||

| – | – | Flotation | Hydrocyclone | – | >92.0 | [63] | |||||

| – | – | Flotation | – | diesel oil | 93.9 | [61] | |||||

| – | – | Flotation | – | Sec-octyl alcohol | 92.4 | [61] | |||||

| – | √ | √ | Flotation | Surface modification | AlCl3 | >99.7 | [43] | ||||

| – | √ | DAF | Coagulation | AlCl3·6H2O | 96.1 | [41] | |||||

| – | √ | DAF | Coagulation | FeCl3·6H2O | 70.6 | [41] | |||||

| – | – | DAF | – | – | 81.0–86.0 | [64] | |||||

| – | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | MDAF | SOPC | CTAB | 81.6 | [65] | |

| – | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | MDAF | SOPC | PDAC | 88.3 | [65] | |

| – | √ | √ | √ | MB flotation | – | Commercial detergent | >98.0 | [66] | |||

| – | – | NB flotation | – | – | 86.0–88.0 | [64] | |||||

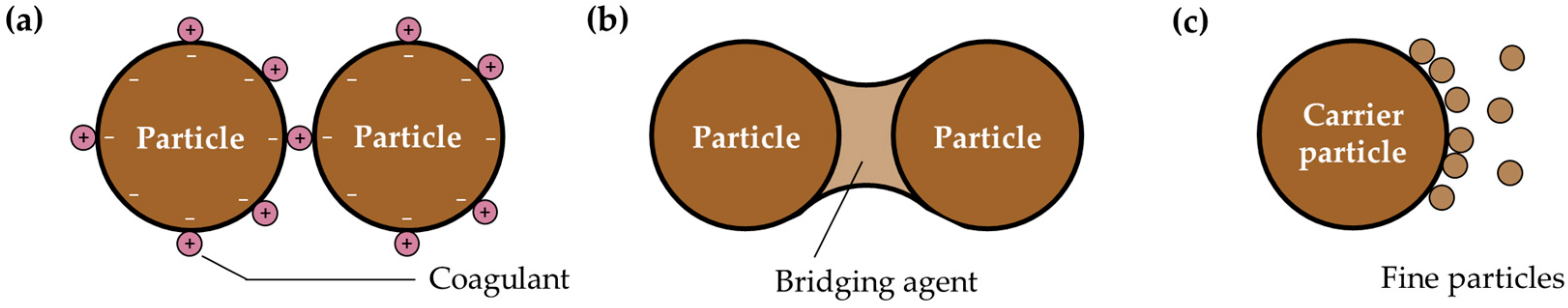

- (a)

- Concentration of surface modifying agents: Across studies, higher dosages of surface-modification and collector agents generally improved MP flotation. AlCl3 enhanced removal efficiency of 1–50 µm MPs from 50–90% to 85–95% [57]. SMSN similarly showed improved removal with increasing dosage [47]. Cationic agents such as CTAB and PDAC increased recovery from about 40% at 0 mg/L to approximately 80% (CTAB) and 90% (PDAC) at higher dosages [49], while CTAB was most effective up to 1.2 mg/L, decreasing beyond 1.4 mg/L [45]. Hydrocarbon collectors, including kerosene, diesel oil, and sec-octyl alcohol, also showed positive dosage–removal trends, rising from around 80–88% at low doses to >90% at higher concentrations up to 0.665 mL/L [49,61].

- (b)

- pH: Most chemical agents showed a strong pH dependence in MP removal. Coagulation using PAC and PAFC achieved the highest efficiency at pH 6 (≈90%), with performance decreasing at both lower and higher pH values, reaching about 75% at pH 10 [53]. Similarly, flotation with AlCl3 and FeCl3 also peaked at pH 6, with removal rates of about 60% and 30%, respectively, before declining to 40% and 15% at pH 8 [41]. In contrast, some agents—such as SOPC—showed no significant pH influence, indicating that pH sensitivity depends strongly on the type of chemical used [65].

- (c)

- Salinity: In general, salinity slightly enhanced MP removal, with saline water achieving around 89%, compared with 85% in deionized water [47]. However, the effect differed by polymer type: PA and PVC showed slightly lower removal efficiencies in saline conditions. At the same time, PS and PET exhibited slight increases compared with their performance in non-saline water [51].

- (d)

- Temperature: Temperature had no significant effect on MP flotation within the tested range of 10–40 °C, with removal efficiency remaining stable across conditions [50]. However, in some treatment processes, thermal exposure can indirectly reduce the floatability of certain polymers, such as PC, by hydrophilizing them, leading to lower removal rates [62].

- (e)

- Treatment time: Studies showed that treatment duration had minimal influence on flotation performance. Extended bubble-generation time did not alter bubble size or concentration, indicating unstable or time-independent bubble characteristics [57,64]. For SOPC, reaction times longer than 5 min produced a stable removal rate, with no further improvement at longer durations [65]. Similarly, DTAC treatment showed no additional benefit beyond 2 min, indicating that prolonged treatment does not enhance MP removal [52].

3.3.2. Removal of Microplastics from Solid Particles Using Flotation

4. Critical Discussion, Future Perspectives, and Conclusions

4.1. Critical Discussion of Technical Findings

4.2. Policy, Economic, and Social Perspectives

4.3. Future Perspectives

- Standardization of protocols: Current studies employ diverse reagents, particle sizes, operating conditions, and matrices, which limit data comparability. Harmonized experimental and reporting guidelines, such as those proposed by Cowger et al. [79], are urgently needed to improve reproducibility, enable cross-study synthesis, and support reliable technology benchmarking.

- Nanoplastics: Most flotation studies still focus on MPs (>1 µm), while systematic investigations on nanoplastics remain limited. Given their higher mobility, bioavailability, and potential toxicity, further research is required to adapt flotation principles and detection methods for nano-sized plastic particles.

- Eco-friendly reagents: Many flotation studies rely on kerosene, synthetic surfactants, or chemical coagulants, raising concerns over secondary pollution and sustainability. Future research should prioritize the development and application of biodegradable, low-toxicity, and biomass-derived collectors or modifiers suitable for environmental systems.

- Pilot and full-scale validation: Nearly all existing studies are conducted at laboratory scale using simplified or synthetic matrices. Pilot-scale demonstrations under realistic wastewater and sediment conditions are essential to evaluate process stability, robustness against matrix complexity, and operational challenges prior to industrial deployment.

- Scale-up and industrial implementation: Transitioning flotation from laboratory to full-scale systems involves challenges related to hydrodynamics, bubble size control, continuous operation, energy demand, froth handling, and integration with existing WWTP units. Future studies should address process optimization, techno-economic assessment, and life-cycle analysis to support feasible large-scale application.

- Hybrid processes: Integrating flotation with other treatment processes such as coagulation, membrane filtration, or advanced oxidation may provide synergistic improvements in efficiency. Systematic evaluation of hybrid flowsheets is needed to determine optimal configurations for different water and sediment scenarios.

- Interdisciplinary integration: Progress in MP flotation requires closer collaboration between mineral processing, environmental engineering, toxicology, and social sciences. Such integration is necessary to develop technically effective solutions that are also environmentally safe and socially acceptable.

- Global governance and treaties: Beyond technical development, effective mitigation of MP pollution requires international policy coordination and legally binding frameworks. Global agreements, similar to climate or hazardous waste treaties, are crucial for controlling transboundary plastic contamination [80].

4.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrady, A.L. Persistence of plastic litter in the oceans. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, M.O.; Abrantes, N.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Nogueira, H.; Marques, J.C.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Impacts of plastic products used in daily life on the environment and human health: What is known? Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 72, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Saito, A.; Murase, N.; Phengsaart, T.; Tabelin, C.B.; Hiroyoshi, N.; Tsunekawa, M. Improvement of hybrid jig separation efficiency using wetting agents for the recycling of mixed-plastic wastes. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2019, 21, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; Silva, A.L.P.; da Costa, J.P.; Mouneyrac, C.; Walker, T.R.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Solutions and Integrated Strategies for the Control and Mitigation of Plastic and Microplastic Pollution. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, K.A. End-of-Waste Criteria for Waste Plastic for Conversion. Technical Proposals. Publications Office of the European Union. 2014. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC91637 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Evode, N.; Qamar, S.A.; Bilal, M.; Barceló, D.; Iqbal, H.M. Plastic waste and its management strategies for environmental sustainability. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Khan, M.H.; Ali, M.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, A.; Nabi, G.; Ali, F.; Bououdina, M.; Kyzas, G.Z. Insight into microplastics in the aquatic ecosystem: Properties, sources, threats and mitigation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 913, 169489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuten, E.L.; Saquing, J.M.; Knappe, D.R.; Barlaz, M.A.; Jonsson, S.; Björn, A.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S.; Yamashita, R. Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2027–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermabessiere, L.; Dehaut, A.; Paul-Pont, I.; Lacroix, C.; Jezequel, R.; Soudant, P.; Duflos, G. Occurrence and effects of plastic additives on marine environments and organisms: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.P. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, C.Q.Y.; Valiyaveettil, S.; Tang, B.L. Toxicity of microplastics and nanoplastics in mammalian systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Kelly, F.J. Plastic and human health: A micro issue? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6634–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Dai, X.; Wang Qvan Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Ni, B.J. Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Detection, occurrence and removal. Water Res. 2019, 152, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Islam, N.; Tasannum, N.; Mehjabin, A.; Momtahin, A.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Almomani, F.; Mofijur, M. Microplastic removal and management strategies for wastewater treatment plants. Chemosphere 2024, 347, 140648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristaldi, A.; Fiore, M.; Zuccarello, P.; Oliveri Conti, G.; Grasso, A.; Nicolosi, I.; Copat, C.; Ferrante, M. Efficiency of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) for microplastic removal: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayal, L.; Yadav, K.; Dey, U.; Das, K.; Kumari, P.; Raj, D.; Mandal, R.R. Recent advancement in microplastic removal process from wastewater—A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyare, P.U.; Ouki, S.K.; Bond, T. Microplastics removal in wastewater treatment plants: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020, 6, 2664–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padervand, M.; Lichtfouse, E.; Robert, D.; Wang, C. Removal of microplastics from the environment. Rev. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 807–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, N.; Parashar, N.; Hait, S. Coagulative removal of microplastics from aqueous matrices: Recent progresses and future perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 899, 165723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, T.; Mohamad Riza, Z.H.; Sheikh Abdullah, S.R.; Abu Hasan, H.; Ismail, N.I.; Othman, A.R. Microplastic removal in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) by natural coagulation: A literature review. Toxics 2023, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarer, S. A review of microplastic removal from water and wastewater by membrane technologies. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poerio, T.; Piacentini, E.; Mazzei, R. Membrane processes for microplastic removal. Molecules 2019, 24, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Hu, X.; Lin, H.; Yu, G.; Shen, L.; Yu, W.; Li, B.; Zhao, L.; Ying, M. Membrane technology for microplastic removal: Microplastic occurrence, challenges, and innovations of process and materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 166183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, S.; Happel, C.M.; Taeger, M.; Flora, G. Settling velocities of small microplastic fragments and fibers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 5653–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Sin, A.; Kim, G.; Khan, S.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Sahle-Demessie, E.; Han, C. Pretreatment methods for monitoring microplastics in soil and freshwater sediment samples: A comprehensive review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 871, 161718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möller, J.N.; Heisel, I.; Satzger, A.; Vizsolyi, E.C.; Oster, S.J.; Agarwal, S.; Laforsch, C.; Löder, M.G. Tackling the challenge of extracting microplastics from soils: A protocol to purify soil samples for spectroscopic analysis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2022, 41, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Ducoli, S.; Tubić, A.; Pustisek, A.; Doletek, D.; Tkalec, Ž. A complete guide to extraction methods of microplastics from complex environmental matrices. Molecules 2023, 28, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, I.; Bacha, A.U.R.; Zhang, L. A review on microplastics separation techniques from environmental media. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, P.; Abhishek, K. Sampling, separation, and characterization methodology for quantification of microplastic from the environment. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 14, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkashvand, M.; Hasan-Zadeh, A. Mini review on physical microplastic separation methods in the marine ecosystem. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2022, 5, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, J.A.; Dobby, G. Column flotation: A selected review. Part I. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1991, 33, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Tripathy, S.K.; Banerjee, P. An overview of reverse flotation process for coal. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2015, 134, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shean, B.; Cilliers, J. A review of froth flotation control. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2011, 100, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, R. The place of systematic reviews in education research. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2005, 53, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal-Snape, D.; Hannah, E.F.S.; Cantali, D.; Barlow, W.; MacGillivray, S. Systematic literature review of primary–secondary transitions: International research. Rev. Educ. 2020, 8, 526–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yue, D.; Wang, H. Insights into mechanism of hypochlorite—Induced functionalization of polymers toward separating BFR—Containing components from microplastics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 36755–36767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiari, A.; Mowla, D. Investigation of microplastic removal from greywater by coagulation and dissolved air flotation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 151, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Bian, K.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhao, H. Is froth flotation a potential scheme for microplastics removal? Analysis on flotation kinetics and surface characteristics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 792, 148345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, H. A clean and efficient flotation towards recovery of hazardous polyvinyl chloride and polycarbonate microplastics through selective aluminum coating: Process, mechanism and optimization. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grob, L.; Zeneli, L.; Ott, E.; Vialetto, J.; Junginger, M.; Hoffmann, T.; Pauer, W. Filter-less separation technique for micronized anthropogenic polymers from artificial seawater. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 2280–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S. The removal efficiency and mechanism of microplastic enhancement by positive modification dissolved air flotation. Water Environ. Res. 2021, 93, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yue, D.; Wang, H. In situ Fe3O4 nanoparticles coating of polymers for separating hazardous PVC from microplastic mixtures. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 407, 127170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, M.; Pitchumani, B. A sustainable approach for removal of microplastics from water matrix using colloidal gas aphrons: New insights on flotation potential and interfacial mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 334, 130198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Somer, T.; Van Melkebeke, M.; Goethals, B.; Gusev, S.; Van der Meeren, P.; Van Geem, K.; De Meester, S. Modelling and application of dissolved air flotation for efficient separation of microplastics from sludges and sediments. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julapong, P.; Ekasin, J.; Katethol, P.; Srichonphaisarn, P.; Juntarasakul, O.; Numprasanthai, A.; Tabelin, C.B.; Phengsaart, T. Agglomeration–flotation of microplastics using kerosene as bridging liquid. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bian, K.; Wang, H.; Wang, C. Insight into the effect of aqueous species on microplastics removal by froth flotation: Kinetics and mechanism. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saczek, J.; Yao, X.; Zivkovic, V.; Mamlouk, M.; Wang, S.; Pramana, S.S. Utilization of bubbles and oil for microplastic capture from water. Engineering 2024, 20, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Bu, J.; Bian, K.; Su, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Surface change of microplastics in aquatic environment and the removal by froth flotation assisted with cationic and anionic surfactants. Water Res. 2023, 233, 119794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y.; Feng, X.; Jia, W.; Liu, M.; Zhao, S. Efficient, quick, and low-carbon removal mechanism of microplastics based on integrated gel coagulation-spontaneous flotation process. Water Res. 2024, 259, 121906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacaphol, K.; Aht-Ong, D.; Coughlan, D.; Hoogewerff, J. Oleo-extraction of microplastics using flotation plus sol-gel technique to confine small particles in silicon dioxide gel. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, W.; Du, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, D. Numerical study on the mechanism of microplastic separation from water by cyclonic air flotation. Water Res. 2024, 247, 122338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, B.; Pihlajamäki, A.; Chew, Y.M.J.; Wenk, J. Microbubble–microplastic interactions in batch air flotation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 449, 137866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Farid, M.U.; Ho, Y.W.; Ma, X.; Wong, P.W.; Nah, T.; He, Y.; Boey, M.W.; Lu, G.; Fang, J.K.H.; et al. Advanced nanobubble flotation for enhanced removal of sub-10 μm microplastics from wastewater. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Pei, F.; Wang, X. Enrichment of microplastic pollution by micro-nanobubbles. Chin. Phys. B 2022, 31, 118104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feilin, H.; Mingwei, S. Ecofriendly removing microplastics from rivers: A novel air flotation approach crafted with positively charged carrier. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 168, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, D.; Shojamejer, T.; Tupinamba Lima, M.; Zukova, D.; Marschall, R.; Schomäcker, R. The performance of carbonate-modified nonionic surfactants in microplastic flotation. Water 2023, 15, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, E.; Liu, X.; Miao, Z.; Jiang, X.; Han, Y. Flotation and separation of microplastics from the eye-glass polishing wastewater using sec-octyl alcohol and diesel oil. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 164, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, C.; Yue, D.; Wang, H.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, L. Exploring flotation separation of polycarbonate from multi-microplastic mixtures via experiment and numerical simulation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Li, X.; Yu, W.; Du, J.; Wang, D.; Yang, X.; Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Yuan, H. A high-efficiency mini-hydrocyclone for microplastic separation from water via air flotation. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 103084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharraz, J.A.; Jia, M.; Farid, M.U.; Khanzada, N.K.; Hilal, N.; Hasan, S.W.; An, A.K. Determination of microplastic pollution in marine ecosystems and its effective removal using an advanced nanobubble flotation technique. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ma, J.; Zeng, S.; Li, X.; Lisak, G.; Chen, F. Advanced treatment of microplastics and antibiotic-containing wastewater using integrated modified dissolved air flotation and pulsed cavitation-impinging stream processes. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Helgason, A.; Leng, R.; Chowdhury, S.; Clermont, N.; Dinh, J.; Aldebasi, R.; Zhang, X.; Gattrell, M.; Lockhart, J.; et al. Removal of microplastics/microfibers and detergents from laundry wastewater by microbubble flotation. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 1819–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bian, K.; Wang, C.; Xie, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H. Is it possible to efficiently and sustainably remove microplastics from sediments using froth flotation? Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 448, 137692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Fischer, B.; Renner, G.; Schoettl, J.; Wolf, C.; Schram, J.; Schmidt, T.C.; Tuerk, J. Efficient and sustainable microplastics analysis for environmental samples using flotation for sample pre-treatment. Green Anal. Chem. 2022, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Bian, K.; Wang, H.; Wang, C. Flotation separation of hazardous polyvinyl chloride towards source control of microplastics based on selective hydrophilization of plasticizer-doping surfaces. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423 Pt A, 127095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Pi, K.; Gerson, A.R. Surfactant-assisted air flotation: A novel approach for the removal of microplastics from municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 884, 163841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, S.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Shaari, K.; Azmai, M.N.A.; Saad, M.Z.; Mat Isa, N.; Nazarudin, M.F. The Burden of Microplastics Pollution and Contending Policies and Regulations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.T.; Bjorkland, R.; Burgess, R.M. Comparing the definitions of microplastics based on size range: Scientific and policy implications. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 207, 116907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chan, F.K.S.; He, J.; Johnson, M.; Gibbins, C.; Kay, P.; Stanton, T.; Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Feng, M.; et al. A critical review of microplastic pollution in urban freshwater environments and legislative progress in China: Recommendations and insights. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 2637–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowger, W.; Willis, K.A.; Bullock, S.; Conlon, K.; Emmanuel, J.; Erdle, L.M.; Eriksen, M.; Farrelly, T.A.; Hardesty, B.D.; Kerge, K.; et al. Global producer responsibility for plastic pollution. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Cai, L.; Sun, F.; Li, G.; Che, Y. Public attitudes towards microplastics: Perceptions, behaviors and policy implications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setälä, O.; Tirroniemi, J.; Lehtiniemi, M. Testing citizen science as a tool for monitoring surface water microplastics. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, V.; Ozunu, A.; Petrescu, D.C.; Stan, A.-D.; Petrescu-Mag, R.M. The influence of media narratives on microplastics risk perception. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Borgogno, F.; Villarrubia-Gómez, P.; Anderson, E.; Box, C.; Trenholm, N. Mitigation strategies to reverse the rising trend of plastics in Polar Regions. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowger, W.; Booth, A.M.; Hamilton, B.M.; Thaysen, C.; Primpke, S.; Munno, K.; Lusher, A.L.; Dehaut, A.; Vaz, V.P.; Liboiron, M.; et al. Reporting Guidelines to Increase the Reproducibility and Comparability of Research on Microplastics. Appl. Spectrosc. 2020, 74, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.; Egger, M.; Slat, B. A global mass budget for positively buoyant macroplastic debris in the ocean. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Matrix | Size [µm] | Polymer Types | Flotation Techniques | Assisted Techniques | Chemicals Used | Removal Efficiency [%] | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | PE | PS | PET | PVC | Others | |||||||

| Soil and sediment | <5000 | √ | √ | Flotation | – | NaOL | 100.0 | [67] | ||||

| 62–206 | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | µSEP | – | 65.0–77.0 | [68] | ||||

| 100–2300 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | DAF | – | – | – | [48] | ||

| Plastic waste | 2000–4000 | √ | Flotation | Hydrophilization | FeCl3 | 100.0 | [69] | |||||

| – | √ | √ | √ | Carrier flotation | Magnetic coating | Fe3O4 | 100.0 | [46] | ||||

| MSWI bottom ash | 0–5000 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | – | NaCl | ~70.95 | [70] | ||

| 0–300 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | – | NaCl | ~60.06 | [70] | |||

| 300–5000 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Flotation | – | NaCl | ~100.00 | [70] | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phengsaart, T.; Srichonphaisarn, P.; Villacorte-Tabelin, M.; Silwamba, M.; Janjaroen, D.; Tabelin, C.B.; Alonzo, D.; Ta, A.T.; Juntarasakul, O. Microplastic Removal by Flotation: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Research Trends. Water 2025, 17, 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233394

Phengsaart T, Srichonphaisarn P, Villacorte-Tabelin M, Silwamba M, Janjaroen D, Tabelin CB, Alonzo D, Ta AT, Juntarasakul O. Microplastic Removal by Flotation: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Research Trends. Water. 2025; 17(23):3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233394

Chicago/Turabian StylePhengsaart, Theerayut, Palot Srichonphaisarn, Mylah Villacorte-Tabelin, Marthias Silwamba, Dao Janjaroen, Carlito Baltazar Tabelin, Dennis Alonzo, Anh Tuan Ta, and Onchanok Juntarasakul. 2025. "Microplastic Removal by Flotation: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Research Trends" Water 17, no. 23: 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233394

APA StylePhengsaart, T., Srichonphaisarn, P., Villacorte-Tabelin, M., Silwamba, M., Janjaroen, D., Tabelin, C. B., Alonzo, D., Ta, A. T., & Juntarasakul, O. (2025). Microplastic Removal by Flotation: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Research Trends. Water, 17(23), 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233394