4.2. Applicability of the Rouse Equation

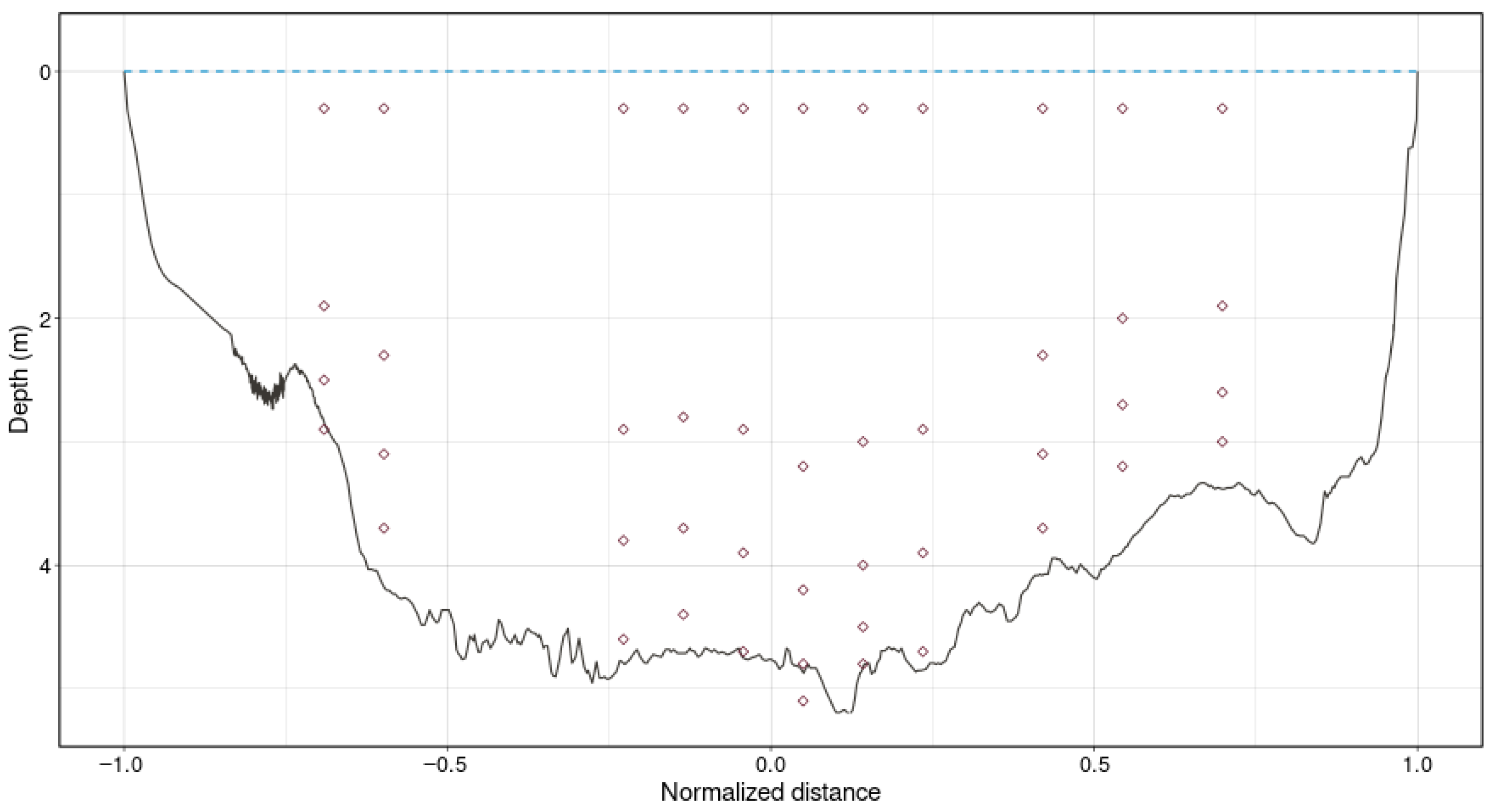

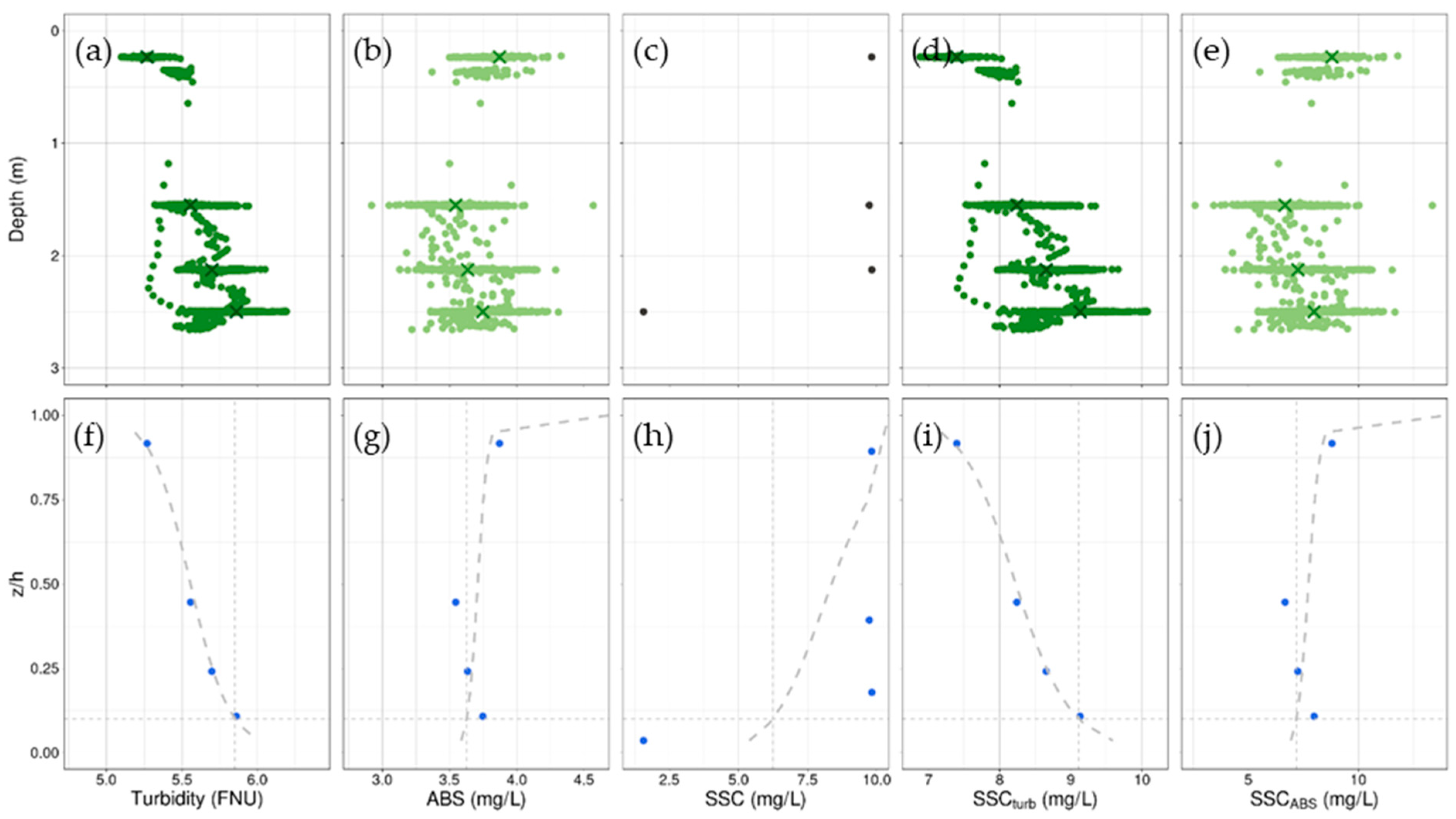

Figure 6 shows an example vertical, depicting the raw data and the process and influence of data averaging and sensor data calibration. Both the ABS and turbidity sensor data show substantial scatter in their single readings, with absolute differences of up to 1 FNU or 1 mg/L, respectively, within the measurement intervals at distinct depths (

Figure 6a,b). Despite this scatter, data averaging enables us to detect vertical trends and calculate Rouse numbers. The same vertical that shows a positive

(0.047) shows a negative

(−0.13), which, in this case, mainly resulted from the deepest measured SSC being substantially smaller than the other water samples of the vertical. In contrast to the sensor readings (

Figure 6a,b), the SSCs from water samples are derived from single measurements, with uncertainties in the order of 10–20% [

7]. Variation in SSCs beyond this range of uncertainty and in contrast to the expectations from Rouse profiles, as depicted in

Figure 6c, are frequently observed in our dataset and may result from short-term variations, e.g., due to turbulent mixing in river systems. The comparison with

, based on uncalibrated turbidity values (FNU), which is around half (0.023) of the

value, shows the importance of turbidity calibration before interpretation of the results is possible.

However, deviations of single SSC measurements in a vertical, as shown in

Figure 6c, do not have a strong influence on SSC

turb and SSC

ABS, which are derived from the regression to SSC from water samples over the entire dataset of each sampling campaign. The calibrated turbidity in

Figure 6i shows a vertical gradient, which can be well-fitted to a Rouse gradient. Nevertheless, the ABS data for this vertical shows that the sensor data might also produce negative values for

, when the absolute values differ very little with depth. This is a rarity in our dataset. The fitted

are generally low, ranging from −0.26 to 0.25 for SSC, from −0.056 to 0.095 for ABS, from −0.016 to 0.047 for SSC

turb, and from −0.049 to 0.056 for SSC

ABS. None of the

values show a correlation with the SSC. The vertical shown in

Figure 6b is one of nine verticals in the entire dataset, which show negative

values, i.e., representing 8.7% of all ABS verticals (

n = 104). For

, negative values were observed at ten verticals (

n = 119, 8.4%), and for

, at 15 verticals (

n = 123, 12.2%).

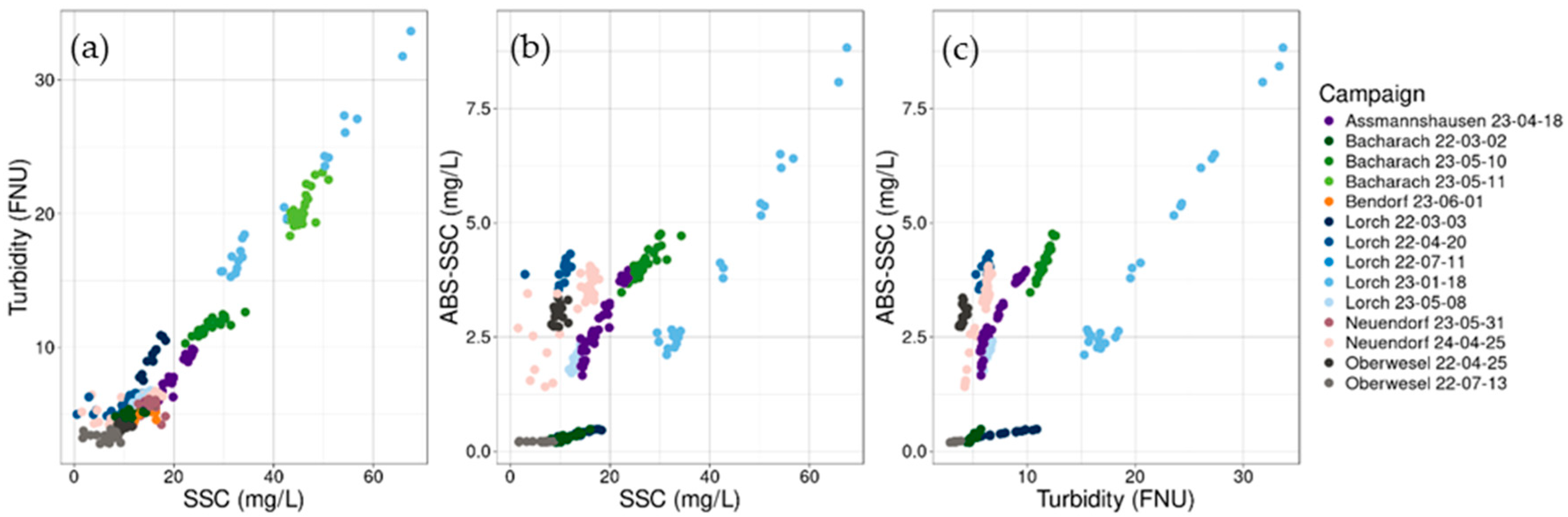

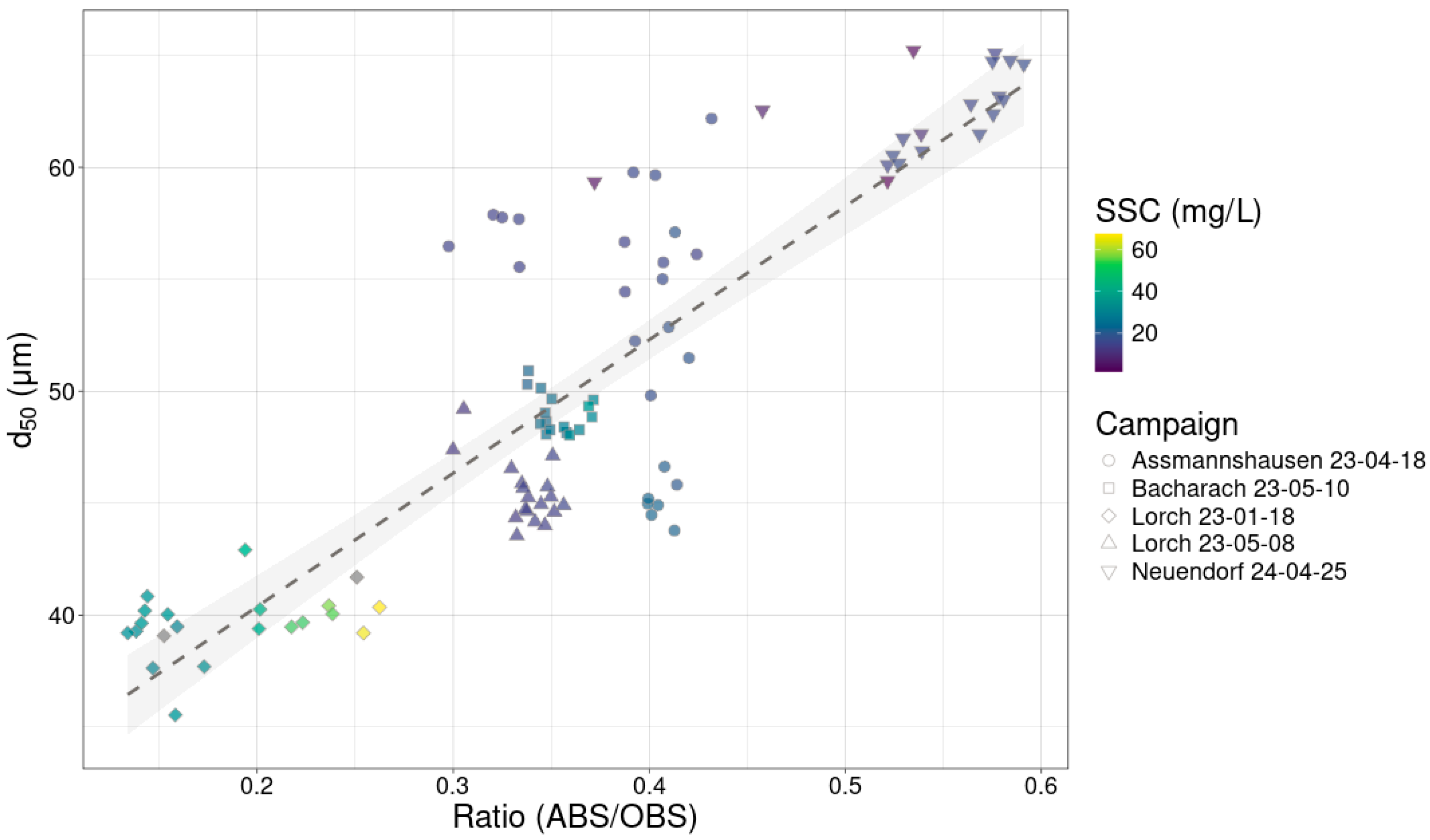

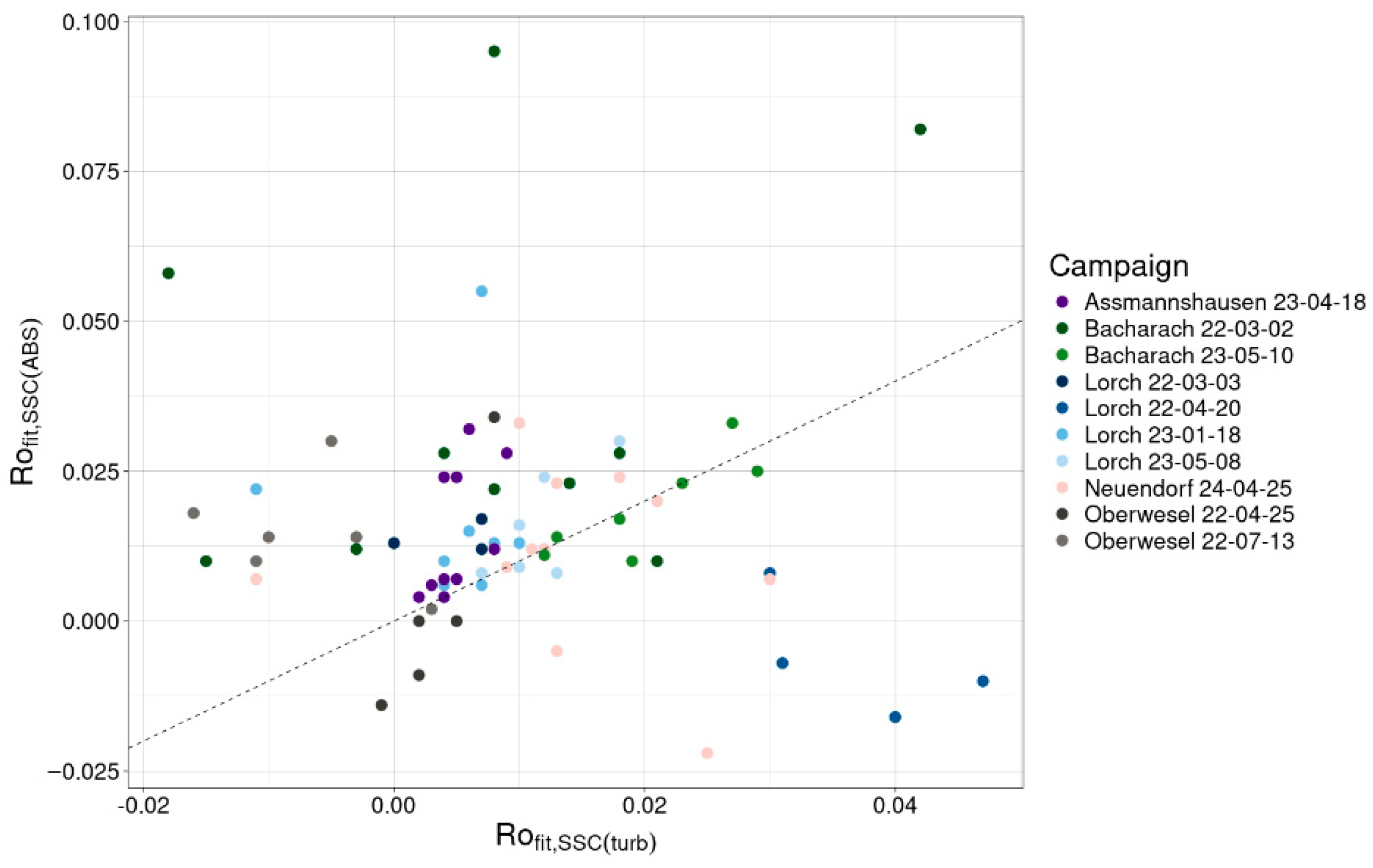

Both

and

show small absolute values (

Figure 7). However, it is notable that the average value of

(0.016) is an order of magnitude larger than the average value of

(8.5 × 10

−3). This can be explained by the larger sensitivity of acoustic systems to larger grain sizes compared to optic systems [

32], which are less uniformly distributed vertically. This can also be seen in

Figure 5, where the ratio of ABS/OBS (turbidity), i.e., their sensitivity comparison, is larger for larger grain sizes.

, derived from the 51 vertical gradients of the suspended sand concentration (i.e., 50 L samples which were sieved with >63 µm) show an average value of 0.10 and range from −0.021 to 0.51. This is again an order of magnitude larger than

, indicating that

is affected by the mixture of the fine (i.e., clay/silt) and sand fractions. The later represents, on average, 9% of the total suspended solids [

22].

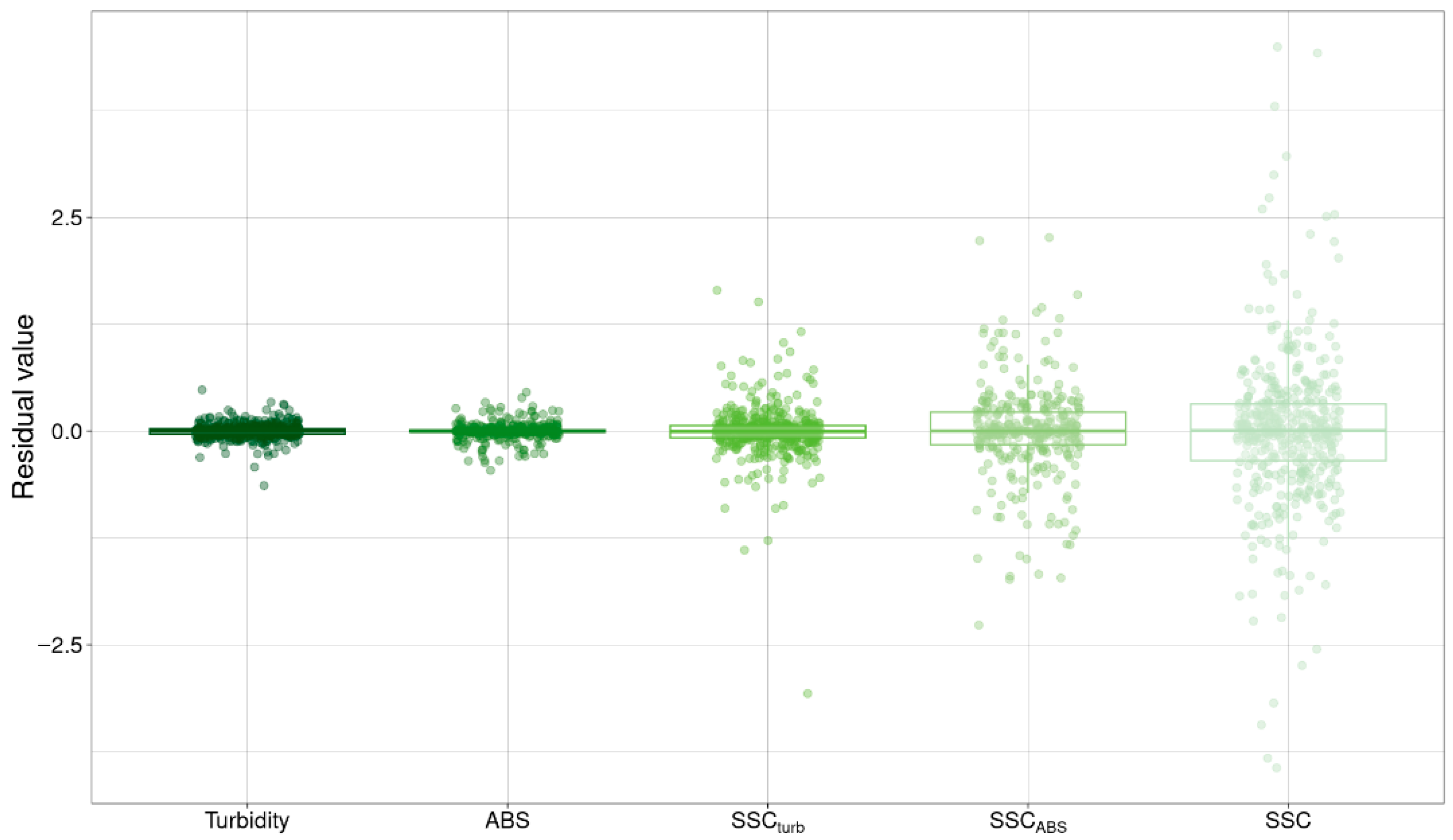

The residual values, i.e., the difference between the measured value and corresponding value of the fitted Rouse profile, for the sensor data are consistently smaller compared to the residuals of the water samples with the average absolute values of 0.052 and 0.048 for turbidity and ABS, respectively. The average absolute value for residuals based on the SSC from water samples is an order of magnitude larger (0.55). Standard deviations are 0.08 for residuals based on turbidity, 0.09 for ABS and 0.88 for SSC from water samples. The residual values for the SSC

turb and SSC

ABS are in the same order of magnitude as for SSC, with an average of absolute values of 0.15 for SSC

turb with a standard deviation of 0.29 and an average absolute value of 0.33 for SSC

ABS with a standard deviation of 0.53. The larger standard deviations of the calibrated sensor data are due to the scatter, introduced by the calibration with water samples. Nevertheless, the SSC

turb is characterized by substantially smaller residual scatter than the SSC from water samples, indicating that the SSC

turb is closer to the expected Rouse distribution than the SSC from water samples (

Figure 8). For this reason, it is used as the base parameter,

, in the following analyses.

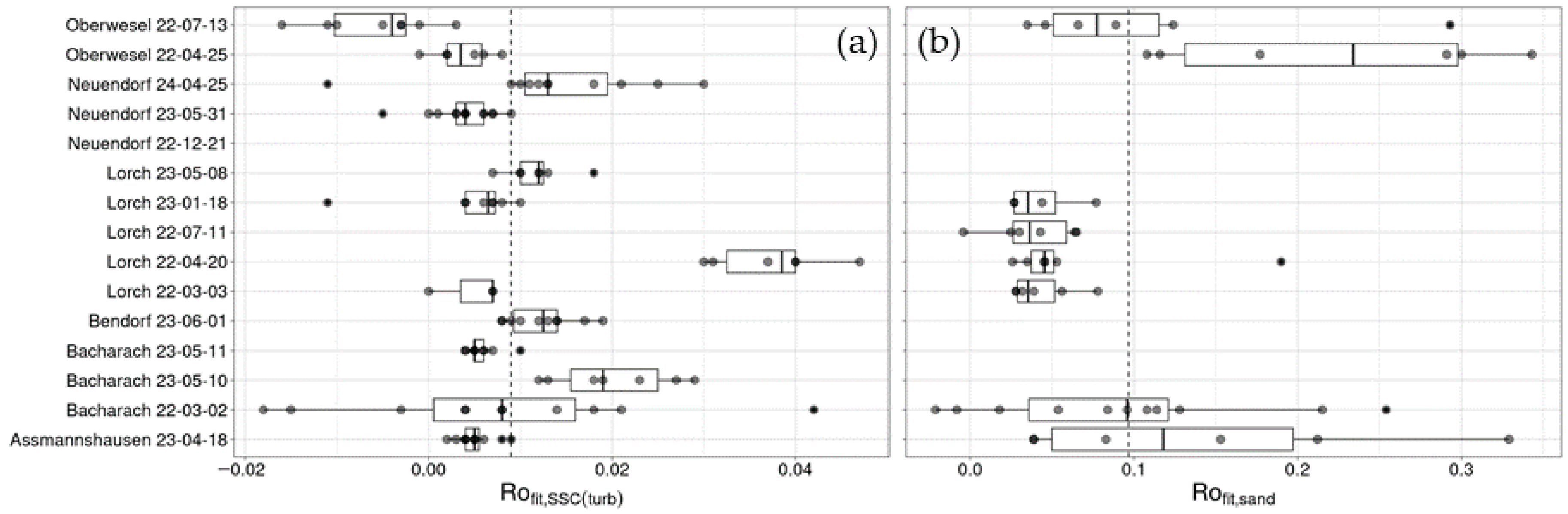

Values of

for the fine fraction vary significantly among several campaigns, with variability within the cross-section during a single campaign being much smaller than between campaigns (

Figure 9a). For the sand fraction, Kruskal–Wallis testing (

p = 0.01) and post hoc testing, using the Bonferroni correction method (

p = 0.01), reveal significant differences, only between the Lorch (11 July 22) and Oberwesel (25 April 2025) campaigns. Among all other campaigns, no significant differences could be found, i.e., the scatter within single campaigns is larger than the differences among campaigns (

Figure 9b).

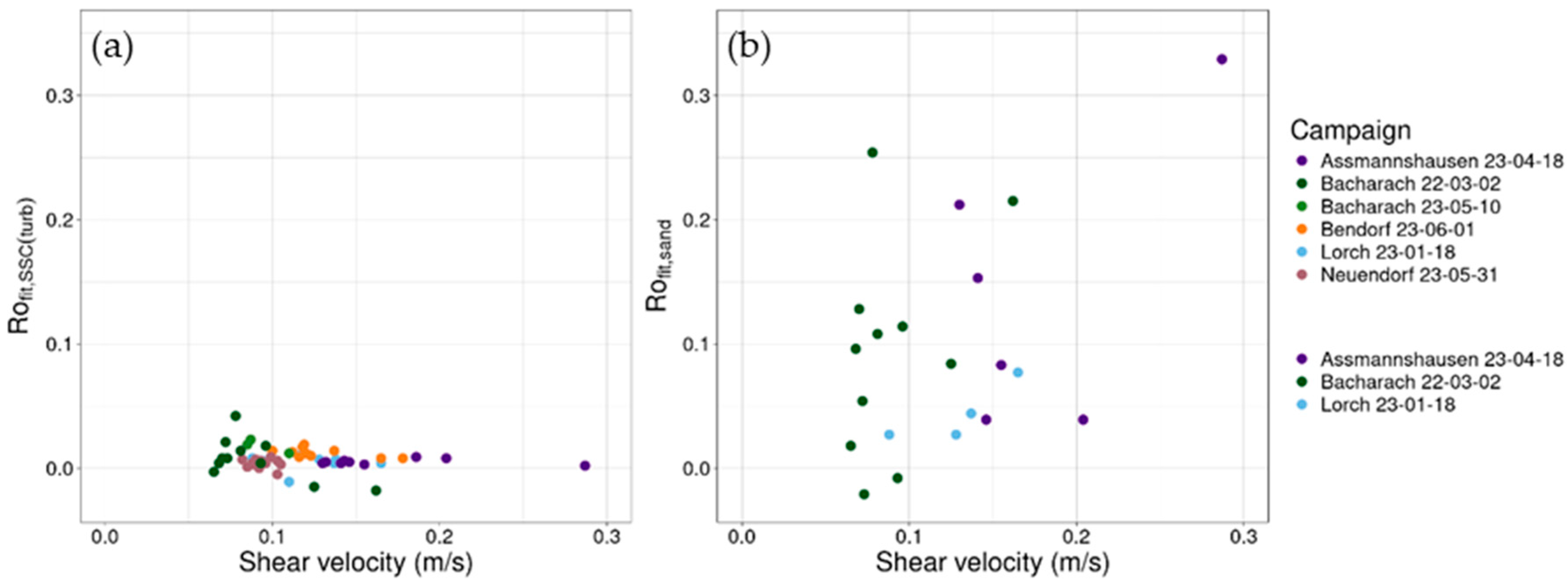

shows no correlation (R

2 = 0.03,

p = 0.13), while

shows a small positive correlation (R

2 = 0.16,

p = 0.04) with shear velocity, which varied between 0.07 and 0.28 with an average value of 0.12 (

Figure 10).

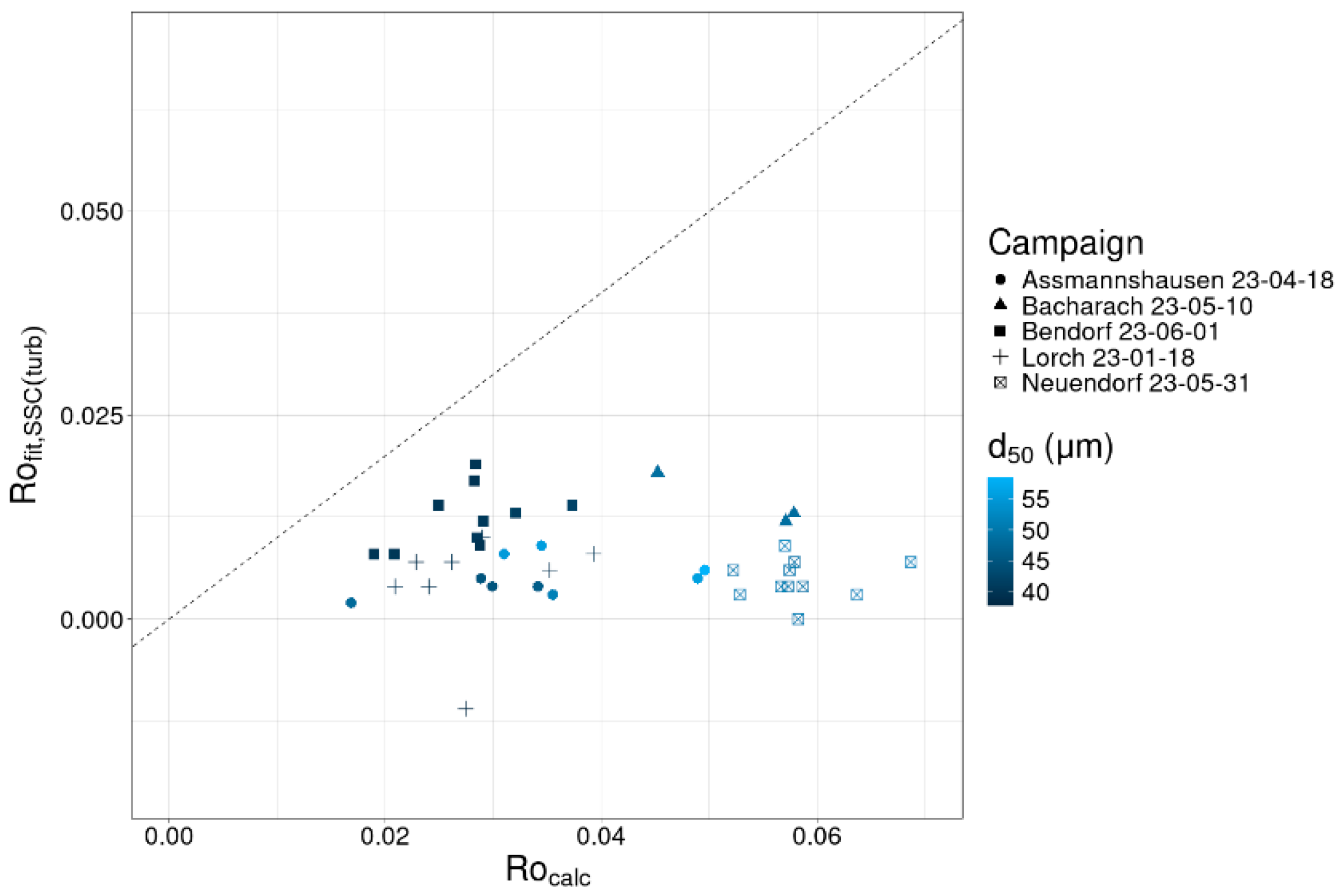

Rouse values calculated from Equation (2) (

) range from 0.017 to 0.069 and are, without exception, larger than those derived from fitted vertical gradients (

), which typically range between 0 and 0.025. As expected,

increases with d

50 with maximum values close to 0.07 (

Figure 11). This theoretically derived dependency on particle size is not visible in the fitted data, which shows no correlation between d

50 and

(R

2 = −0.01). When comparing

with

, smaller d

50 values tend to be closer to the theoretical values than the larger values of d

50; albeit, they are still smaller than theoretically expected when calculated with an assumed density of 2650 kg/m

3. The absolute difference between

and

does significantly correlate with d

50 (R

2 = 0.47,

p = 4.1 × 10

−7). This derivation indicates that larger particle sizes may show a higher degree of flocculation, i.e., their density values are further away from the expectations for primary particles.

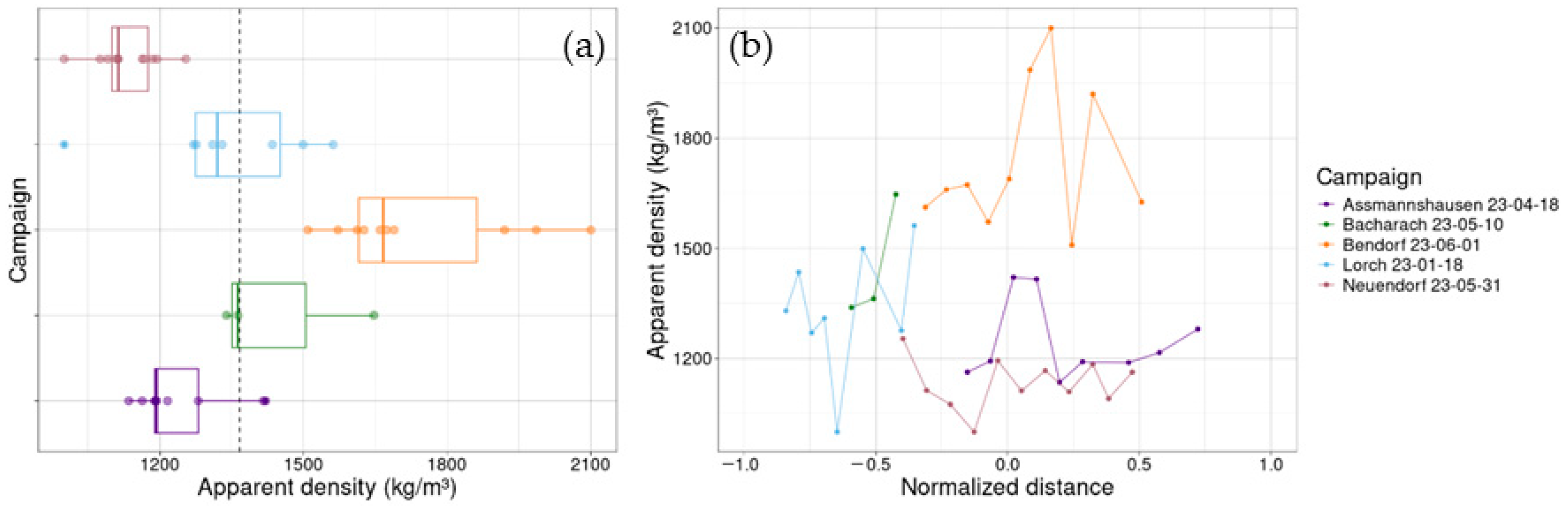

Thus, effective particle densities within the waterbody are likely lower than the usually assumed density of quartz (

Figure 12). Adopting the density in Equations (2) and (3) such that

results in a mean effective density value of the 41 analyzed verticals of 1367 kg/m

3 with a minimum value of 1000 kg/m

3, which is the calculation minimum, due to the calculation procedure of submerged specific gravity and a maximum value of 2100 kg/m

3, which is still substantially smaller than the density of quartz. Effective densities for Assmannshausen, Bacharach, Lorch and Neuendorf do not differ significantly, while Kruskal–Wallis (

p = 5 × 10

−6) and post hoc testing with Bonferroni correction shows significant differences between the campaign at Bendorf and the campaigns at Assmannshausen and Neuendorf, which are characterized by smaller densities (

Figure 12a). The larger densities at Bendorf can be explained by significantly smaller particle sizes, with an average d

50 of 40.4 µm compared to 52.2 µm at Assmannshausen and 50.8 µm at Neuendorf. Since the measurements at Neuendorf and Bendorf are separated by only 7 km and have water level differences of 7 cm, hydrological reasons for these particle size differences are implausible. More likely, the difference in particle size is due to the turbulent breakup of flocs along the flow path between the two sites or due to the mobilization of different material. This section of the river contains two elongated islands (approximately 4 km and 2 km in length), which divide the flow three ways just upstream of the measurement site at Bendorf. This increases turbulence and may serve as an additional source of suspended matter. Also, similar particle sizes were measured at Lorch (18 January 2023, with an average d

50 of 39.4 µm. Here, however, values of

were significantly lower than at Bendorf (

p = 0.017), with no differences in shear velocities, indicating differences in mineral composition.

Laterally, none of the campaigns show any patterns (

Figure 12b), except for Bacharach (10 May 2023), which shows a lateral pattern that is similar to that of the lateral conductivity measurements of this campaign (

Figure 13), indicating that the lateral differences in effective density here may stem from the SPM originating from different water masses. However, the correlation between the density and conductivity is not significant (R

2 = 0.94,

p = 0.11) and is only based on three data points.

We expected minimal vertical differences in SSC, since the sampling sites are usually dominated by particle sizes in the silt range that have often been reported to be transported as a well-mixed wash load [

33]. This is confirmed by the in situ PSD measurements with an averaged d

50 of 49.1 µm, i.e., coarse silt. However, even though the suspended load is dominated by small particles (mainly silt), full vertical mixing is not always given. This extends the findings of, e.g., Bungartz et al. (2006), Lamb et al. (2020), and Nghiem et al. (2022), who calculated increased settling velocities for clay and silt-sized particles due to flocculation, resulting in vertical concentration differences [

12,

34,

35]. The discrepancy of the expected theoretical density and the calculated apparent, effective density also points towards flocculation within the system, although our in situ PSD measurements show that possible flocculation of primary particles hardly results in flocs above the silt range. This is in accordance with studies analyzing the influence of turbulence and shear-stress on floc formation, finding that turbulence helps in the formation of flocs to a certain degree but prevents the formation of larger flocs [

34,

35,

36].

Despite outliers in SSC, the calibrated turbidity is still suitable to detect fine vertical differences. The data are robust, since the calibration is performed based on the average turbidity values and the SSC values of the whole campaigns. This finding is backed up by the residual analysis of Rouse distributions. Here, the sensor data consistently shows residual values an order of magnitude smaller than those of the water sample-based SSC measurements. Therefore, the Rouse analysis again stresses the uncertainties connected to analyses based solely on water samples, and in general, our results emphasize the added value that surrogate sensor measurements provide to detect subtle differences within rivers for an improved understanding of suspended sediment transport in the system.

The Rouse theory holds up in most cases, although our results show that in some circumstances, as presented in this study, i.e., particles sizes primarily in the silt range, low SSC, and when shear velocities are constantly large enough to keep the transported matter suspended, the Rouse framework reaches its limits and loses its predictive capacity. In general, the detected values for are very small, with some verticals showing larger concentrations towards the surface, i.e., . Therefore, using calculated Rouse gradients based on Equations (1) and (2) when extrapolating from surface measurements to deeper parts of the water column would lead to a substantial overestimation of SPM towards the bed, and to large errors in load calculations. This shows that predicting Rouse gradients is generally limited by the unknown transport conditions and properties of the suspended sediments in rivers, highlighting the importance of in situ measurements for an improved understanding of conditions for suspended sediment transport and accurate load estimations. Here, turbulence is consistently large enough to suspend and vertically mix not only the main particle size fraction of coarse silt but also sand and larger-sized particles, as can be deduced by the generally low values of for both and . However, there is a significant but small positive correlation between shear velocity and , indicating that the vertical distribution of this fraction is less homogenous for larger shear velocities. This suggests that higher shear velocities mobilize more sand particles that remain predominantly concentrated near the bed. Additionally, this may hint that increasing shear stress may mobilize coarser grain sizes that are otherwise immobile under a flow with smaller shear velocities, i.e., representative of a shift in transported grain size distribution.

4.3. Lateral SSC Distribution

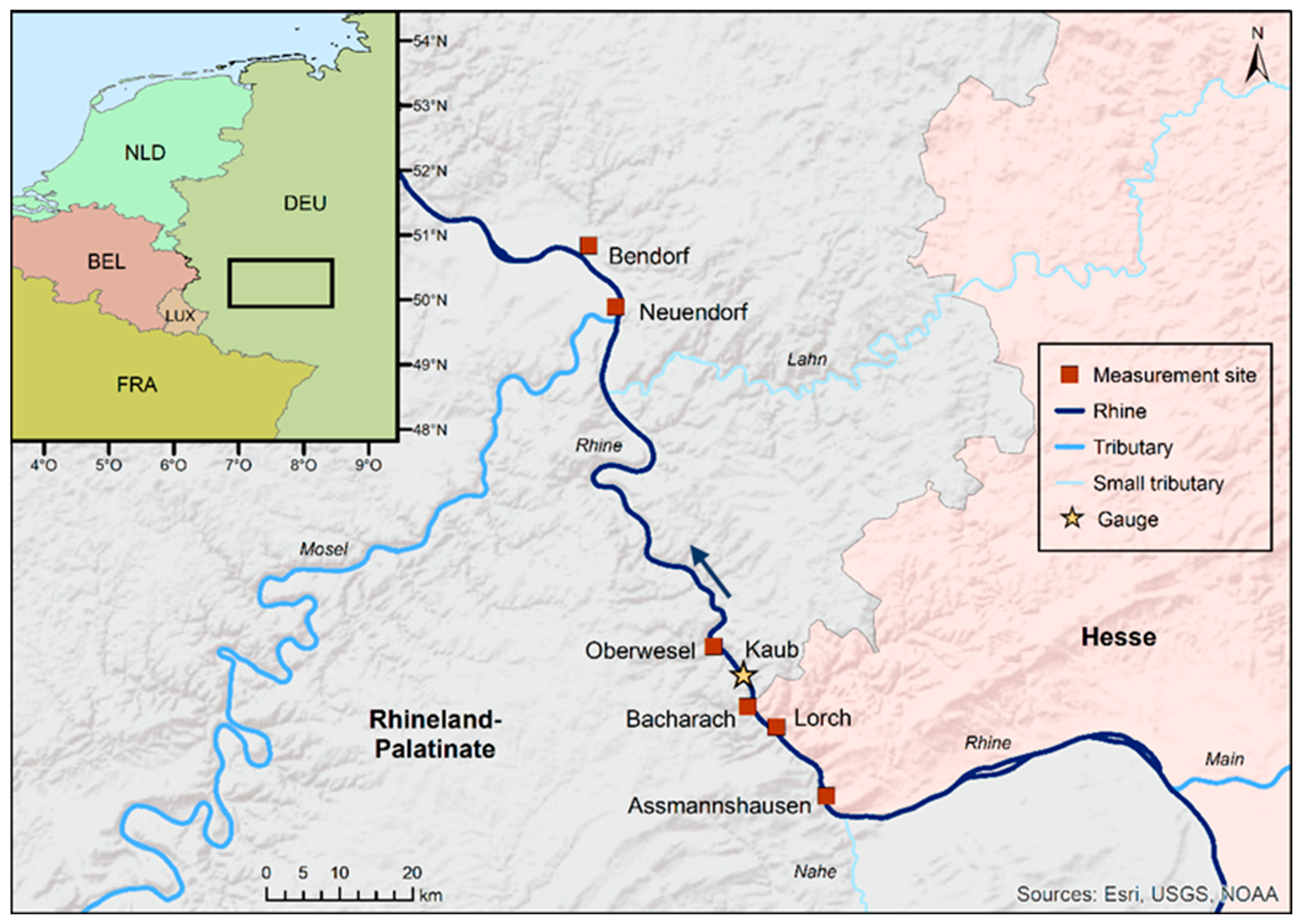

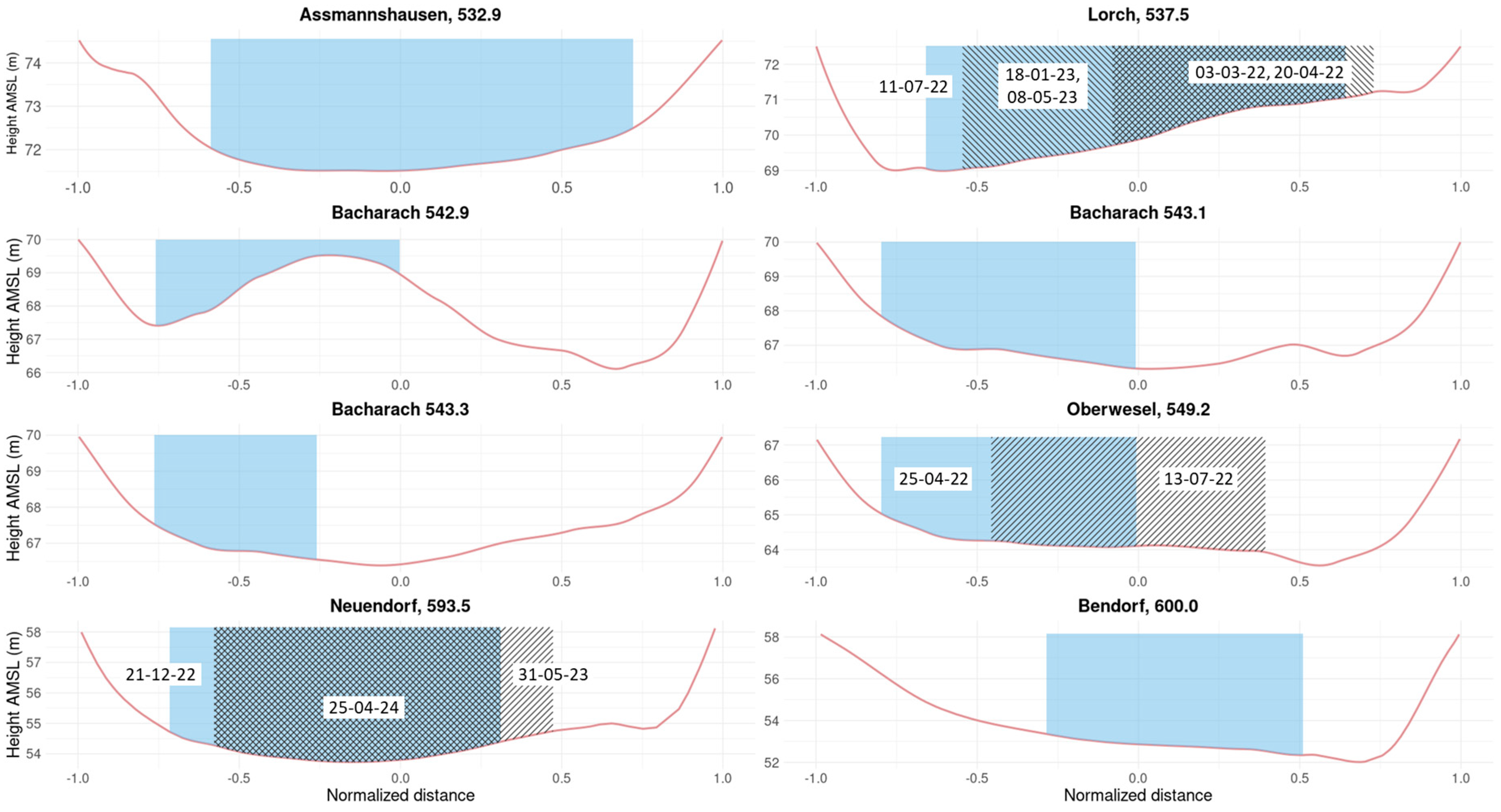

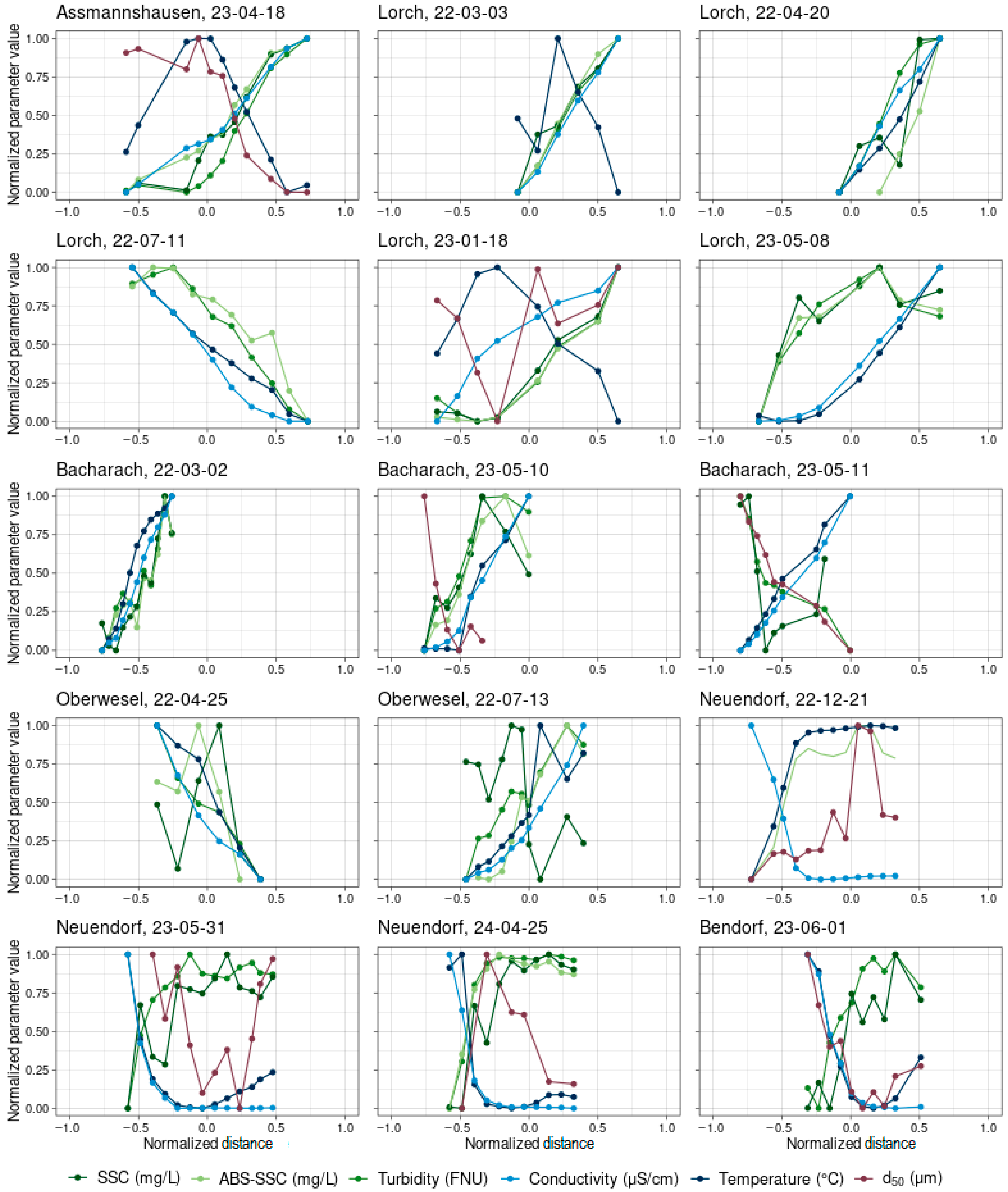

Significant lateral trends were detected within every campaign, at least for some parameters (

Figure 13). If trends are visible for the SSC, turbidity and acoustic backscatter, they always follow the same direction. This is also true for conductivity for every campaign upstream of the Mosel tributary, except for Bacharach (11 May 2023). Downstream of the Mosel tributary, the trend of conductivity always opposes that of SSC and turbidity and acoustic backscatter, indicating the influence of the Mosel tributary on lateral gradients. Four types of trend curves can be observed: (i) a linear trend, e.g., Bacharach (2 March 2022) or Lorch (3 March 2022), (ii) a strong local gradient at some point along the cross-section with more or less constant values to the left and right of that, (iii) a mixture of type (i) and (ii), e.g., Lorch (18 January 2023, 8 May 2023) and (iv) no trend. Type (ii) gradients are especially observable for sampling sites that are closely downstream of tributaries, e.g., Neuendorf (31 May 2023) and Bendorf (1 June 2023). Type (iii) is characterized by a slowly increasing or decreasing gradient over the cross-section and smaller parts with constant values towards one side of the measured cross-sectional width, e.g., Lorch (8 May 2023). Type IV (no trends) is not observable for whole campaigns, but rather for single parameters. Especially temperature and d

50 tend to show variable patterns along the cross-section, e.g., Assmannshausen (18 April 2023) and Lorch (18 January 2023), but also SSC, e.g., Oberwesel (13 July 2022) and Bacharach (11 May 2023). Temperature, in general, shows very little variation along the cross-section, with differences between the leftmost and rightmost measured vertical always being below 1 °C. Since it can be altered by sunlight, ship traffic and its proximity to the banks, it is prone to show patterns differing from the other, more inherent water parameters. The large degree of variation within the d

50 curves is probably due to high scatter in the data. When the single LISST-200X measurements are not disturbed, information about d

50 offers an important means to understand underlying processes within a river cross-section. But since they are rather easily disturbed, due to environmental or mechanical disturbances such as air bubbles, thermal microstructures, obstruction of the beam path or improper positioning due to flow disturbances [

37], the presented statistics for the cross-sections only consider the parameters of acoustic backscatter, turbidity, SSC and conductivity.

Seven of fifteen campaigns show linear trends (type i) for at least one parameter, making it the most common trend in our dataset. Linear trends indicate that sampling took place over a part of the cross-section that lies within a mixing zone, since the parameters consistently increase or decrease towards one site but do not reach a plateau. We argue that these changes are due to the mixing of different water bodies and not due to shifts in SSC-maxima due to curvature, since conductivity changes in corresponding patterns. However, as the different campaigns at the sampling site Lorch illustrate, these trends can vary over time. Here, three of the five campaigns show a type (i) while the others show type (iii) trends, characterized by a slowly increasing or decreasing gradient over the cross-section and smaller parts with constant values towards one side of the measured cross-sectional width, indicating that the type of lateral trend may change under different conditions. Type (ii) trends, which show a break-point behavior, are mostly restricted to the sampling sites Neuendorf and Bendorf that lie 1.3 Rh-km and 7.8 Rh-km, respectively, downstream of the confluence of Mosel and Rhine, and therefore, closely downstream from the confluence of two large rivers. At Neuendorf, the influence of the tributary Mosel is visible by the very strong lateral gradient around −0.5 normalized distance, i.e., 250 m from the right bank, marking the border between the two water masses of Mosel and Rhine. This is consistent for each campaign and parameter (except d50) measured here. For Bendorf, the strong lateral transition is less pronounced and shifted further to the right side of the river around −0.1 normalized distance, indicating that the mixing of the two water masses has progressed further.

When considering the scatter of the data, conductivity is the most consistent parameter for measuring lateral variability, which is likely due to different water masses along the cross-section. In some cases, like Assmannshausen, conductivity shows the same lateral pattern as SSC. However, it is prone to changes that are independent of the SSC distribution, illustrated by the two campaigns at Bacharach, separated by one day, where the direction of the lateral conductivity trend inverses (10–11 May 2023). The reason for this is presumably a shift in the water mass origin, since the discharge increased from 2100 to 2300 m3/s overnight. Also, downstream of the confluence of the Mosel, conductivity consistently opposes the lateral trends of the SSC. Therefore, it cannot be used as a means to approximate the SSC, but it can serve as a reliable means to gauge lateral mixing of two water masses downstream of confluences.

The turbidity and acoustic backscatter sensors follow the lateral trends of SSC at every campaign and even detect significant lateral trends when there are none detectable via water samples, as can be seen at the campaign at Oberwesel (

Figure 13). Acoustic backscatter and turbidity correlate with the SSC, with an R

2 > 0.5 for every campaign except for the two campaigns at Oberwesel (

Table 2), which are characterized by very noisy water sample SSC data. As in the case of vertical trends, the turbidity sensor is also superior to the acoustic backscatter sensor in the detection of significant lateral trends, due to less scatter in the data and a larger percentage of fines in the SPM.

The leftmost and rightmost measured verticals showed ratios of 0.75 for turbidity, 0.72 for the water sample’s SSC, and 0.67 for acoustic backscatter, i.e., relative differences of 25–33%, with relative changes in median particle sizes being substantially smaller (9%). Therefore, changes in the sensor data are probably due to changes in the SSC, rather than changes in particle sizes, which is also supported by the large differences in SSC of 6.5 mg/L between the leftmost and rightmost measured vertical, on average. This again emphasizes the large uncertainties introduced in the load calculations, based on the location of the water samples. The absolute differences for every campaign and parameter are shown in

Table 3.

Significant lateral trends are present for >90% of campaigns for ABS and turbidity data and for 70% of campaigns for SSC from water samples (

Table 4).

Lateral differences within our study are probably due to tributary influence and incomplete mixing of two water masses with different SSCs. This is evident when considering the lateral conductivity trends that always either follow or oppose the SSC trends, but are similar in strength, and how they change laterally. Conductivity shows considerably less fluctuation than SSC and the ratio among rivers is rather stable, with the conductivity of the Mosel being consistently larger than that of the Rhine River. Since differences in conductivity stem from different water mass origins, and since these differences are laterally significant within every measurement campaign, they must indicate incomplete mixing of two water bodies. This is in accordance with other studies, e.g., Böhme (2006), who found that the lateral distribution of conductivity in the river Elbe is influenced by tributaries of up to 185 km upstream of the measurement site and Lazo et al. (2024), who even used conductivity as a chemical tracer for flow partitioning in a mixing model [

38,

39].

During the campaigns at Bacharach, sampling was limited to the left half of the river’s cross-section, therefore missing data at the thalweg. This is also the case for the campaigns at Oberwesel, Lorch and Bendorf, albeit that here, data were gathered at the geometrical center of the cross-section. We acknowledge that due to the absence of data of the thalweg, which could not be sampled due to the constraints outlined in

Section 3.1, the hydrodynamic conditions in the deepest part of these cross-sections remain unknown, which may weaken the results of the lateral SSC distribution. However, lateral patterns observed at these sites do not differ from those obtained during campaigns in which the thalweg was sampled. Therefore, these data gaps are not considered to undermine the general conclusions drawn from this study.

4.4. Implications for SPM Monitoring in Large River Systems

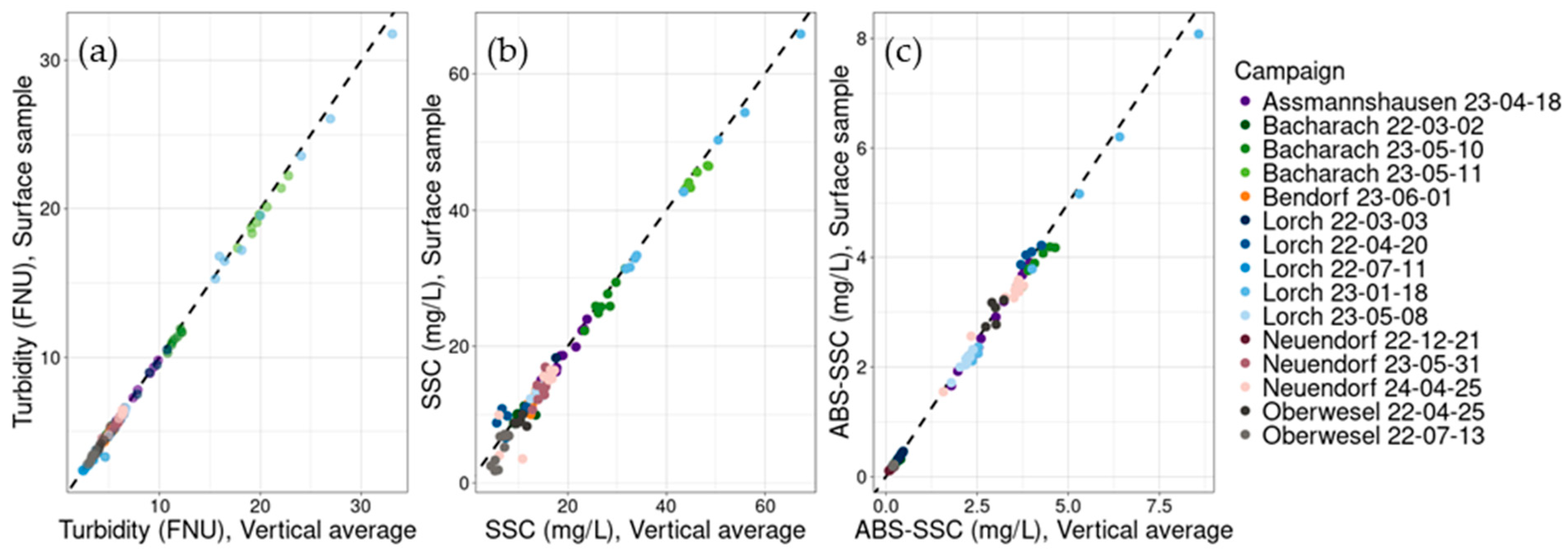

The overall small Rouse numbers are also reflected in the small difference between the surface SSC and the depth-averaged SSC values, as shown in

Figure 14, where all points are plotted very close to the 1:1 line. Surface measurements from the water sample’s SSC, as well as for turbidity and ABS, underestimate the average concentrations by 3% for turbidity and ABS, and 5% for the water sample’s SSC. Surface measurements of the suspended sand yielded an average value of 78% compared to the average values of the complete verticals.

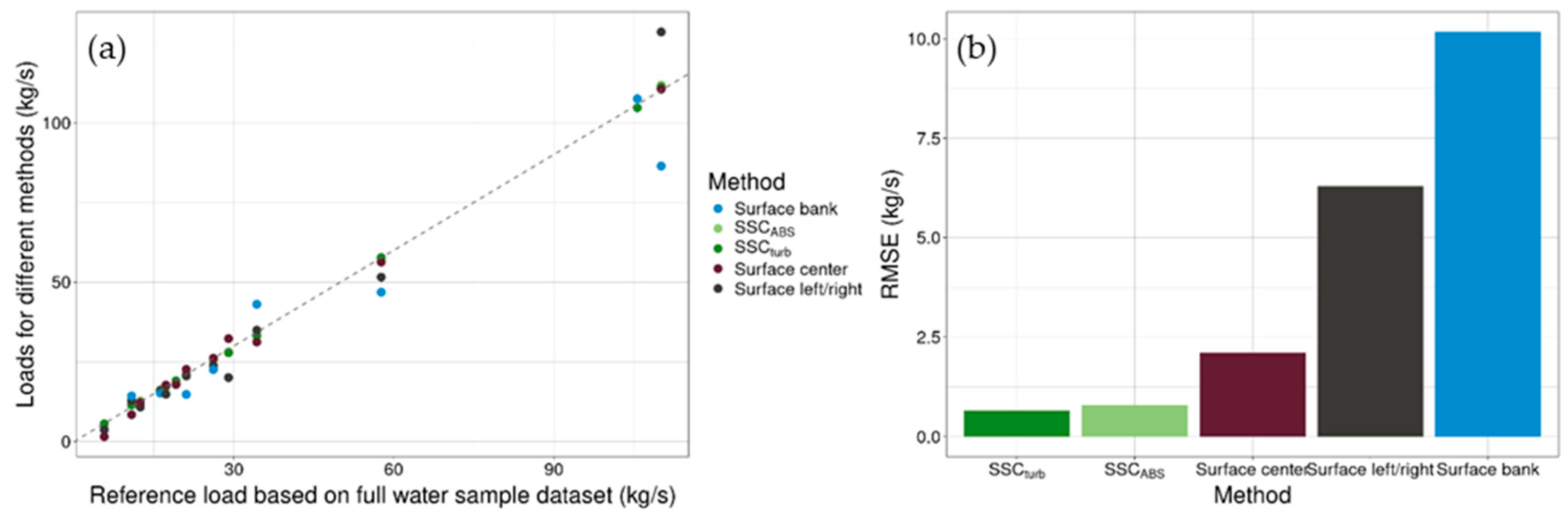

The comparison of the calculated loads, based on the full water sample dataset, multi-point calibrated turbidity and different surface sampling techniques, shows that loads calculated based on calibrated turbidity are hardly any different to the loads based on full cross-sectional water sampling. The largest errors occur due to lateral gradients and sampling only one location, close to the bank. However, taking two surface water samples from the verticals located furthest apart still introduces a larger error into the load calculations than a single surface water sample taken at the center of the river (

Figure 15).

The spatial analysis highlights the importance of both the lateral and vertical gradients of suspended sediment within river channels. Our results reveal that the lateral gradients of suspended matter are typically an order of magnitude smaller than the vertical gradients. However, the total difference in sensor data and SSC between the left and right banks is an order of magnitude larger than that between the water surface and the channel’s bottom when extrapolating the data of the calculated gradients, due to the much larger distance over which these gradients apply. This observation is in accordance with findings in Slabon et al. (2025) [

16]. Considering only the verticals that show a significant trend and multiplying their gradients with the average largest depth per campaign of 4.3 m yields the maximum differences between the surface and channel bottom of 0.67 FNU (turbidity), 0.19 mg/L (ABS) and 3.9 mg/L (water samples). This scenario, assuming the maximum depth throughout the dataset, as well as significant trends at every vertical, still yields smaller absolute results than the comparison of the average values of the leftmost and rightmost measured verticals. Considering that we were mostly only able to cover the central parts of the cross-sections, the lateral differences between the banks are likely to be even larger if considered for the full cross-section. An approximation can be calculated by multiplying the calculated lateral gradients, based on the trend analysis with the mean river width of our sampling sites of 350 m, yielding 5.95 FNU (turbidity), 1.75 mg/L (ABS) and 15.4 mg/L (SSC). Although this is probably an overestimation, it shows the limitations of point monitoring stations that are located only on one side and close to a riverbank, especially for calculating suspended sediment loads. On the other hand, our study shows that water properties measured at the surface do not differ much from the average conditions over the water column. This is shown by the vertical ratio analysis, the generally small detected Rouse numbers, and the RMSE analysis of load estimates, based on the surface samples. Our results therefore show that uncertainties introduced by a lateral sampling position are larger than the uncertainties introduced by assuming full vertical mixing, and hence, representative sampling at the surface. We suspect that this is true for all large rivers, such as the Rhine, where turbulence is usually strong enough to fully suspend and mix the transported particles vertically, as is shown by the non-existent correlation between the

values and the shear velocity. We therefore recommend sampling at the center of the river, rather than near the banks. Our results suggest that if only one sampling depth close to the surface is feasible, the results are still representative and additional sampling in larger depths adds little benefit for load calculations. Under these conditions, remote sensing tools, which mainly detect the water properties near the water surface, may also provide useful information for the large-scale SSC monitoring in rivers and may even be used to gauge the substantial lateral differences and include them in the annual load estimates [

40,

41,

42].

However, our analyses also show that the suspended sand fraction behaves differently. We found a weak but significant positive correlation between

and shear velocity, indicating that larger shear stresses lead to the transport of larger amounts of sand and larger particles close to the riverbed. Surface sampling therefore provides a cost-effective and reliable estimate for the fine fraction, which dominates the annual suspended load with 91%, and in terms of flux monitoring the underrepresentation of the sand fraction in surface samples, which still represent 78% of the average vertical value, is negligible [

22]. Nevertheless, for research questions addressing riverbed morphodynamics, sediment sorting or storage and remobilization, the measurement of transported sand remains essential [

43,

44,

45,

46].

Recording the vertical variability of the SSC in flowing waters is only possible by using heavy weights, which prevent the measuring device from drifting with the current. These heavy weights in turn require the use of a powerful crane attached to a large vessel, which is expensive and requires a large crew. Our findings from the Rhine suggest that instead of relying on large crews and vessels to measure the vertical and lateral variability of the SSC in river cross-sections, turbidity sensors may offer a reliable alternative. Compared to traditional and labor-intensive SSC measurements from water samples, turbidity measurements are faster and show less scatter in the data. The statistical analysis shows that turbidity correlates well with SSC distributions across the entire dataset and is superior to water samples and acoustic backscatter in resolving both vertical and lateral differences. Under similar conditions, as observed in our study, i.e., large and turbulent rivers with low SSC and predominantly silt-sized particles, we argue that the measurement of turbidity that is close to the surface is sufficient and representative for the whole water column and calibration, with three to five water samples taken over the cross-section sufficing to yield robust and reliable data. Therefore, by measuring lateral turbidity profiles close to the surface obtained from a small vessel, accurate loads can be calculated efficiently. Smaller vessels require fewer crew members, usually just two or three people, which reduces operational costs and allows for sampling closer to riverbanks, improving the lateral coverage of the channel cross-section. Additionally, shorter time spent at the location of specific verticals will avoid issues, e.g., with large cargo vessels along busy waterways.

The reduced need for a crew, equipment and post-processing, along with the overall reduction in costs, allows for more frequent measurement campaigns, which could provide deeper insights into lateral SSC variations over time. This is a necessary development, since lateral differences in the SSC are still often neglected, even though their influence may far exceed vertical differences. For optimal calibration, water samples should be taken after analyzing the lateral turbidity profile, in the areas of highest and lowest turbidity, which, based on our dataset, are likely near the riverbanks. To account for variability in the SSC measurements from water samples, we recommend collecting at least three samples at these locations and averaging the results. Interpolation between these SSC data points, based on the lateral calibrated turbidity profile, should then yield robust results for the dominant transport of fine sediment and cost-efficient accurate load estimates.