Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Groundwater for a Managed Aquifer Recharge Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

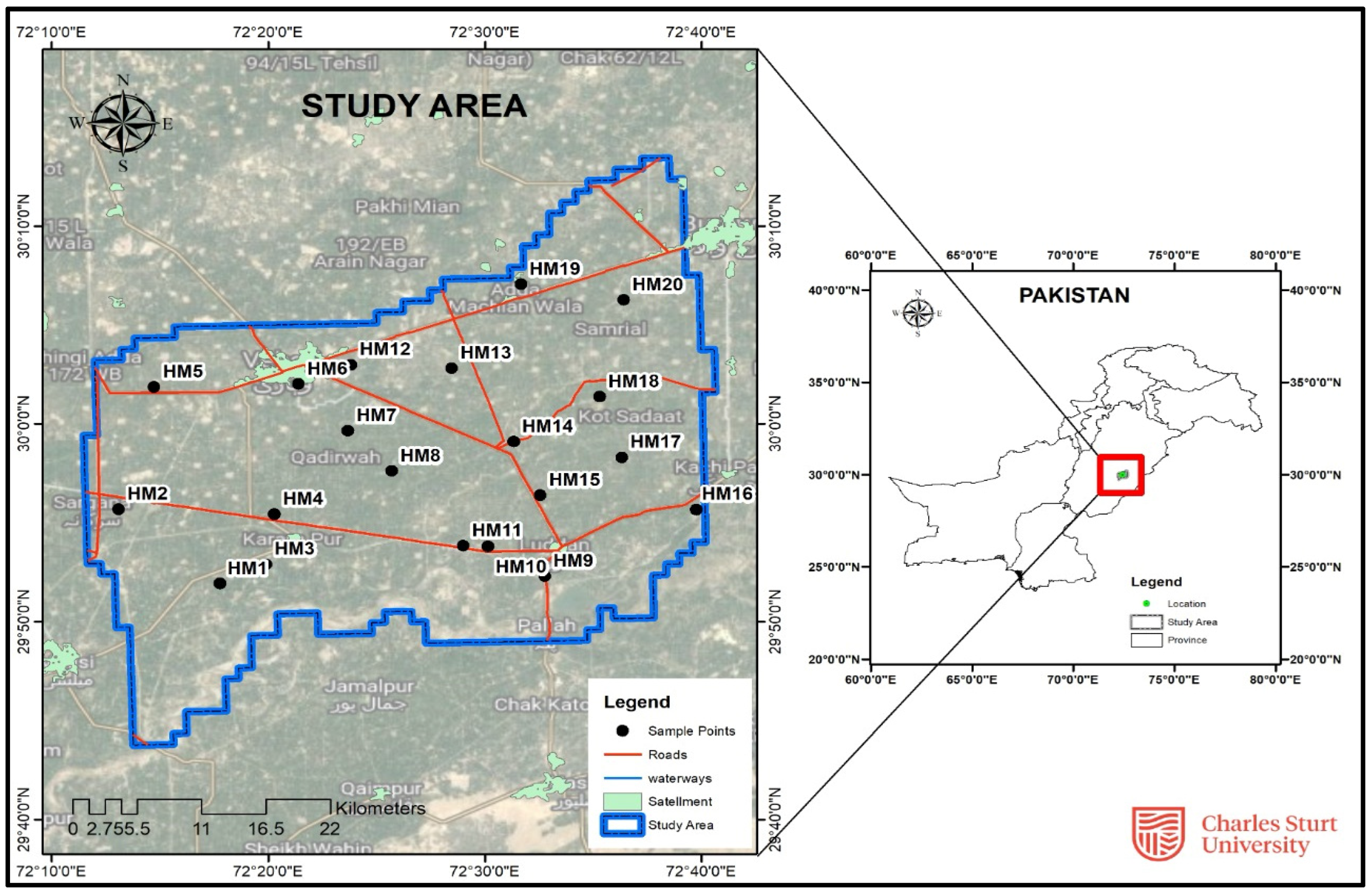

2.1. Description of Study Area

2.2. Water Sampling and Laboratory Analysis

2.3. Methods for Interpretation

2.3.1. Geostatistical Analysis

2.3.2. Geospatial Analysis

2.3.3. Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r)

2.3.4. Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI)

2.3.5. Heavy Metal Index (HI)

3. Results

3.1. General Descriptive Analysis

3.1.1. Geostatistical Analysis

3.1.2. Pearson’s Correlation Analysis

3.2. Water Quality for Irrigation

3.2.1. Analytical Parameters

3.2.2. Geospatial Analysis

3.3. Water Quality for Drinking

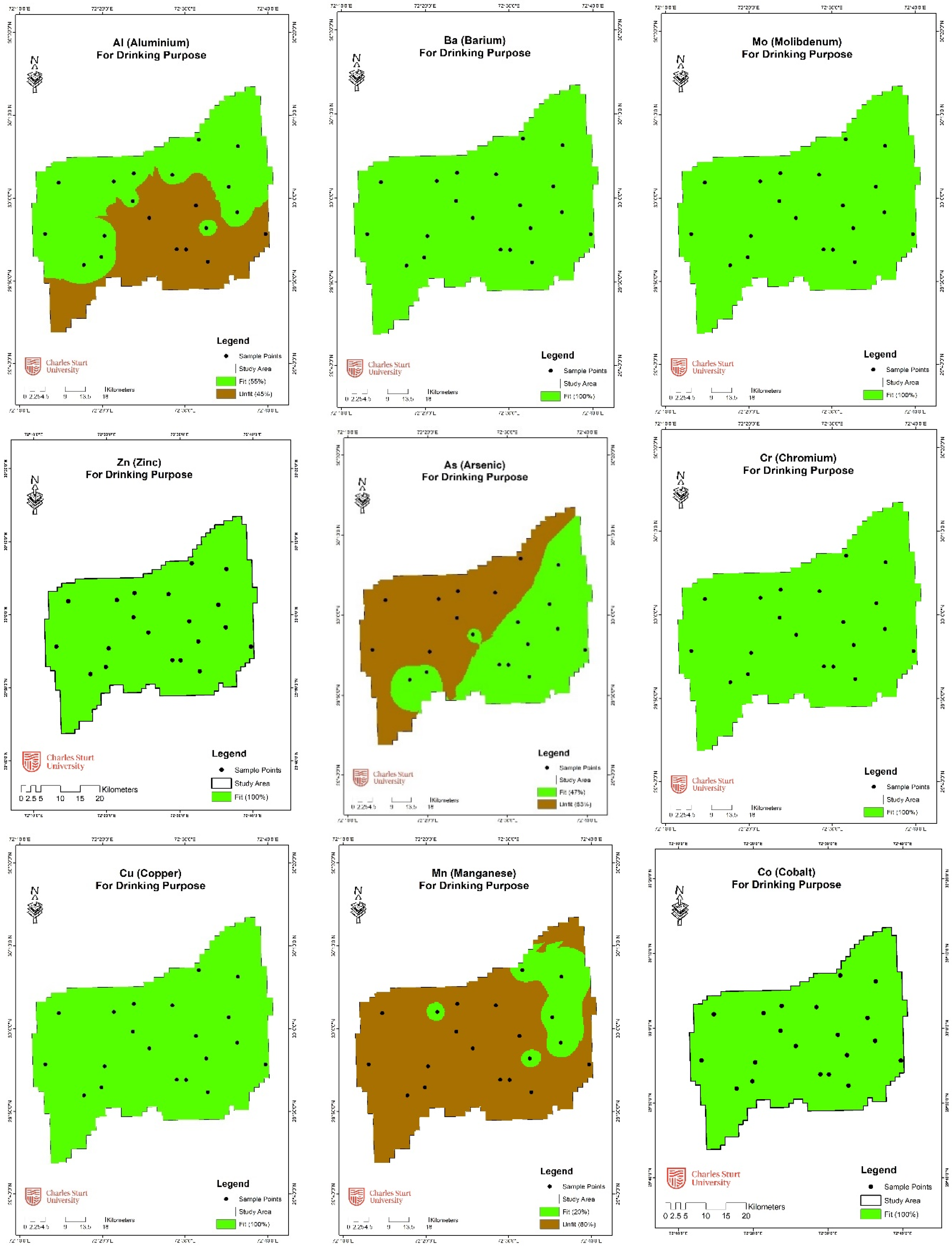

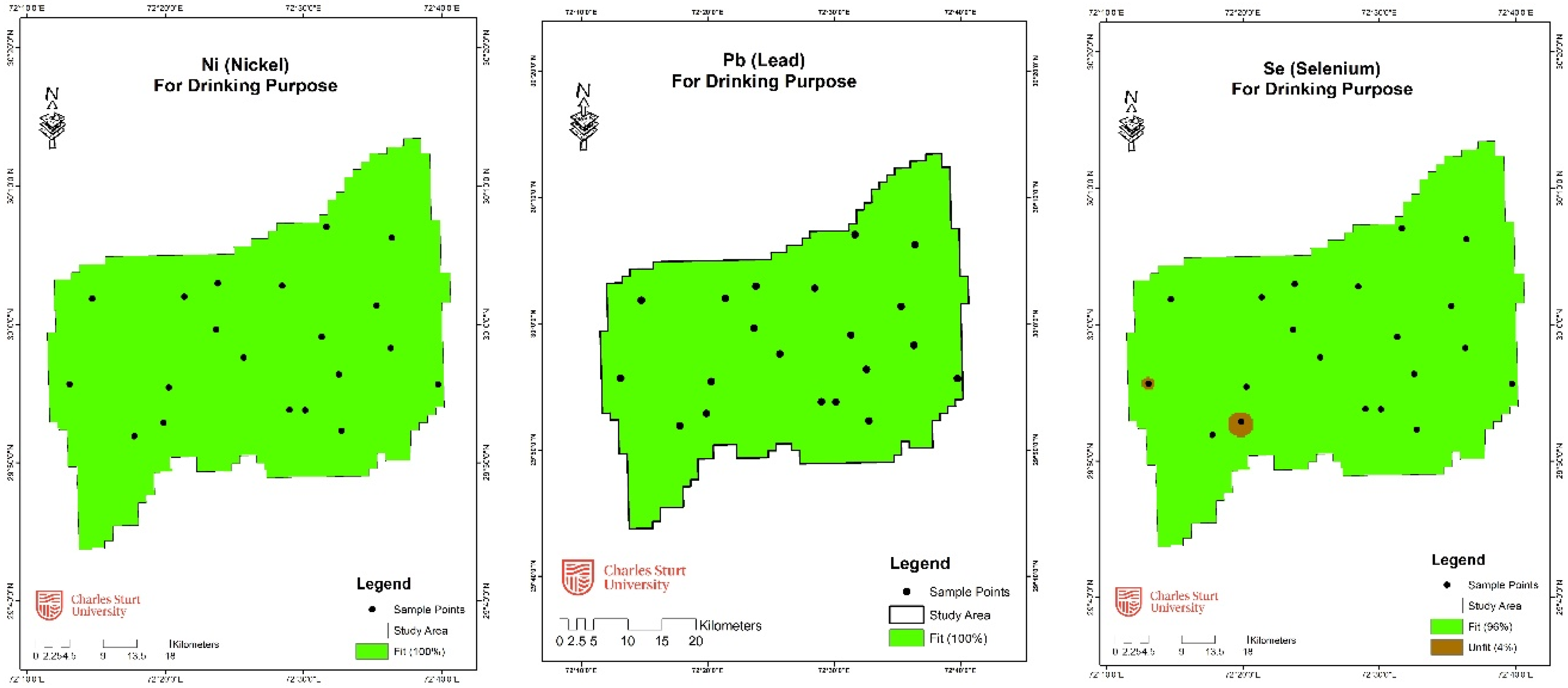

3.3.1. Analytical and Geospatial Analysis

3.3.2. Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI)

3.3.3. Heavy Metal Index (HI)

3.4. Overall Groundwater Quality

3.5. Suitability of Surface Water

3.5.1. Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI)

3.5.2. Heavy Metal Index (HI)

3.5.3. Surface Water Suitability and Comparison with Groundwater

4. Risk Assessment and Discussions

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dikshit, A.; Choukiker, S.K. Global Water Scenario: The Changing Statistics. 2005. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255644494 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Goswami, J.; Bhattacharjya, R.K. Assessment of Groundwater Based Public Drinking Water Supply System of Kamrup District, Assam, India using a Modified Water Quality Index. Pollution 2021, 7, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First Addendum; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke, R.; Wachholz, A.; Mehl, S.; Foglia, L.; Niemann, C.; Doll, P. Importance of Spatial Resolution in Global Groundwater Modeling. Ground Water 2020, 58, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, T.; Cuthbert, M.; Ferguson, G.; Perrone, D. Global Groundwater Sustainability, Resources, and Systems in the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 48, 431–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Hussain, I.; Rasool, A.; Xiao, T.; Farooqi, A. Comparison of two alluvial aquifers shows the probable role of river sediments on the release of arsenic in the groundwater of district Vehari, Punjab, Pakistan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRI. Groundwater Behavior in Rechna Doab-Punjab-Pakistan; Research Report No IRR-GWMC/101; Groundwater Management Cell, Irrigation Research Institute, Irrigation Department, Government of the Punjab: Lahore, Pakistan, 2015.

- Zheng, Y.; Vanderzalm, J.; Hartog, N.; Escalante, E.F.; Stefan, C. The 21st century water quality challenges for managed aquifer recharge: Towards a risk-based regulatory approach. Hydrogeol. J. 2022, 31, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasin, S.; Adam, M.; Idris, A.M. Water quality index and water quality standards for the assessment of groundwater Quality in great Kordufan states, Sudan. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2022, 31, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, A.; Farooqi, A.; Xiao, T.; Masood, S.; Kamran, M.A.; Bibi, S. Elevated levels of arsenic and trace metals in drinking water of Tehsil Mailsi, Punjab, Pakistan. J. Geochem. Explor. 2016, 169, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakir-Hassan, G.; Akhtar, S.; Shabir, G.; Rafique, H.; Khan, M.A.H. Groundwater and nutritional health challenges- A case study from Indus river system in Pakistan. J. Nutr. Health Food Eng. 2022, 12, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWQA. Assessing Groundwater Quality: A Global Perspective: Importance, Methods and Potential Data Sources; WWQA: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Natasha; Shahid, M.; Niazi, N.K.; Khalid, S.; Murtaza, B.; Bibi, I.; Rashid, M.I. A critical review of selenium biogeochemical behavior in soil-plant system with an inference to human health. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Ma, T.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Qin, Y.; Du, Q. Impacts of leachate of landfill on the groundwater hydrochemistry and size distributions and heavy metal components of colloids: A case study in NE China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 5713–5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, M.B.; Niazi, N.K.; Bibi, I.; Rahman, M.M.; Naidu, R.; Dong, Z.; Shahid, M.; Arshad, M. Unraveling Health Risk and Speciation of Arsenic from Groundwater in Rural Areas of Punjab, Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 12371–12390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Niazi, N.K.; Dumat, C.; Naidu, R.; Khalid, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Bibi, I. A meta-analysis of the distribution, sources and health risks of arsenic-contaminated groundwater in Pakistan. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonta, R.; Cassin, D.; Pini, R.; Dominik, J. Assessment of heavy metal and As contamination in the surface sediments of Po delta lagoons (Italy). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 225, 106235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilli, M.A.; Nikolaidis, N.P.; Karatzas, G.P.; Kalogerakis, N. Identifying the controlling mechanism of geogenic origin chromium release in soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Q.; Shaheen, S.; Bilal, M.; Tariq, M.; Zeb, B.S.; Ullah, Z.; Ali, A. Chemical pollutants from an industrial estate in Pakistan: A threat to environmental sustainability. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, B.; Richter, A.; Ng, K.T.W.; Salama, A. Effects of groundwater metal contaminant spatial distribution on overlaying kriged maps. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 22945–22957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameen, N.; Amjad, M.; Murtaza, B.; Abbas, G.; Shahid, M.; Imran, M.; Naeem, M.A.; Niazi, N.K. Biogeochemical behavior of nickel under different abiotic stresses: Toxicity and detoxification mechanisms in plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 10496–10514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Dumat, C.; Niazi, N.K.; Xiong, T.T.; Farooq, A.B.U.; Khalid, S. Ecotoxicology of heavy metal (loid)-enriched particulate matter: Foliar accumulation by plants and health impacts. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2019, 253, 65–113. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.; Niazi, N.K.; Rinklebe, J.; Bundschuh, J.; Dumat, C.; Pinelli, E. Trace elements-induced phytohormesis: A critical review and mechanistic interpretation. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, 1984–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kumar, V. Heavy metal toxicity: An update of chelating therapeutic strategies. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2019, 54, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakir-Hassan, G.; Hassan, F.R.; Punthakey, J.F.; Shabir, G.; Khan, M.A.H. Groundwater Contamination from Drainage Effluents in Punjab Pakistan. J. Agric. Res. Pestic. Biofertil. 2022, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Panda, S.N.; Saxena, C.K.; Verma, C.L.; Uzokwe, V.N.E.; Krause, P.; Gupta, S.K. Optimization Modeling for Conjunctive Use Planning of Surface Water and Groundwater for Irrigation. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2016, 142, 04015060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakir-Hassan, G.; Akhtar, S.; Shabir, G.; Hassan, F.R.; Ashraf, H.; Sultan, M. Water budget study for groundwater recharge in Indus River Basin, Punjab (Pakistan). H2Open J. 2023, 6, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Pinelli, E.; Dumat, C. Tracing trends in plant physiology and biochemistry: Need of databases from genetic to kingdom level. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, A.; Xiao, T.; Farooqi, A.; Shafeeque, M.; Masood, S.; Ali, S.; Fahad, S.; Nasim, W. Arsenic and heavy metal contaminations in the tube well water of Punjab, Pakistan and risk assessment: A case study. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 95, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizullah, A.; Khattak, M.N.; Richter, P.; Hader, D.P. Water pollution in Pakistan and its impact on public health—A review. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakir-Hassan, G.; Akhtar, S.; Shabir, G.; Hassan, F.R. Valuing groundwater for irrigated agriculture towards food security in Punjab, Pakistan. J. Agric. Sci. Agrotechnol. 2023, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WB. High and Dry: Climate Change, Water, and the Economy; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik, A.K.; Alamdar, A.; Katsoyiannis, I.; Shen, H.; Ali, N.; Ali, S.M.; Bokhari, H.; Schafer, R.B.; Eqani, S.A. Mapping human health risks from exposure to trace metal contamination of drinking water sources in Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 538, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakir-Hassan, G.; Hassan, F.R.; Khan, S.A.; Punthakey, J.F.; Akhtar, S.; Shabir, G. Water Security Challenges and Opportunities in Lahore—A City of Pakistan: In the Global Water Security Issues, Series 4, Water Security and Cities—Integrated Urban Water Management, UNESCO. 2023. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388100# (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Zakir-Hassan, G.; Allan, C.; Punthakey, J.F.; Baumgartner, L.; Ahmad, M. Groundwater Governance in Pakistan: An Emerging Challenge. In Water Policy in Pakistan: Issues and Options; Ahmad, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakir-Hassan, G.; Punthakey, J.F.; Allan, C.; Baumgartner, L. Integrating Groundwater Modelling for Optimized Managed Aquifer Recharge Strategies. Water 2025, 17, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRI. Recharge of Aquifer for Groundwater Management in Punjab (2016–2019); Report No IRR-GWMC/121; Groundwater Management Cell, Irrigation Reserach Institute (IRI), Irrigation Department: Lahore, Pakistan, 2019.

- Ross, A. Benefits and Costs of Managed Aquifer Recharge: Further Evidence. Water 2022, 14, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderzalm, J.L.; Dillon, P.J.; Tapsuwan, S.; Pickering, P.; Arold, N.; Bekele, E.B.; Barry, K.E.; Donn, M.J.; McFarlane, D. Economics and Experiences of Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) with Recycled Water in Australia; Australian Water Recycling Centre of Excellence: Brisbane, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, K.; Vanderzalm, J.; Miotlinski, K.; Dillon, P. Assessing the Impact of Recycled Water Quality and Clogging on Infiltration Rates at A Pioneering Soil Aquifer Treatment (SAT) Site in Alice Springs, Northern Territory (NT), Australia. Water 2017, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA_Victoria. Guidelines for Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR)—Health and Environmental Risk Management; EPA_Victoria: Docklands, VIC, Australia, 2009.

- Natasha, N.; Shahid, M.; Murtaza, B.; Bibi, I.; Khalid, S.; Al-Kahtani, A.A.; Naz, R.; Ali, E.F.; Niazi, N.K.; Rinklebe, J.; et al. Accumulation pattern and risk assessment of potentially toxic elements in selected wastewater-irrigated soils and plants in Vehari, Pakistan. Environ. Res. 2022, 214 Pt 3, 114033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelic, P.; Hoanh, C.T.; D’haeze, D.; Vinh, B.N.; Viossanges, M.; Chung, D.T.; Dat, L.Q.; Ross, A. Evaluation of managed aquifer recharge in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 44, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, D.L.; Reba, M.L.; Czarnecki, J.B. Managed aquifer recharge using a borrow pit in connection with the Mississippi River Valley alluvial aquifer in northeastern Arkansas. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 77, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.; Dillon, P.; Vanderzalm, J.; Toze, S.; Sidhu, J.; Barry, K.; Levett, K.; Kremer, S.; Regel, R. Risk assessment of aquifer storage transfer and recovery with urban stormwater for producing water of a potable quality. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 2029–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, P.; Dashora, Y.; Maheshwari, B.; Dillon, P.; Singh, P.; Kumar, A. Managed Aquifer Recharge at a Farm Level: Evaluating the Performance of Direct Well Recharge Structures. Water 2020, 12, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Abbas, F.; Mahmood, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Gul, M.; Yamin, M.; Aslam, B.; Imtiaz, M.; Elahi, N.N.; Qureshi, T.I.; et al. Human health risk of heavy metal contamination in groundwater and source apportionment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 19, 7251–7260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.M.; Eskander, S.B.; Mahmoud, H.H.; Abdou, M.I. Groundwater quality and health assessments based on heavy metals and trace elements content in Dakhla Oasis, New Valley Governorate, Egypt. Water Sci. 2022, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Younas, M.; Sharif, H.M.A.; Wang, C.; Yaseen, M.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Yvette, B.; Lu, Y. Heavy metals contamination, potential pathways and risks along the Indus Drainage System of Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 151994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GOP. Pakistan-Economic Survey 2017–18: Economic Adviser’s Wing; Finance Division, Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2018; p. 247.

- Sindhu, A.S. District Vehari: Hazard, Vulnerability and Development Profile; Rural Development Policy Institute (RDPI): Islamabad, Pakistan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, S.; Shahid, M.; Natasha; Shah, A.H.; Saeed, F.; Ali, M.; Qaisrani, S.A.; Dumat, C. Heavy metal contamination and exposure risk assessment via drinking groundwater in Vehari, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 39852–39864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IRI. Research Studies on Artificial Recharges of Aquifer in Punjab; Research Report No IRR-Phy/579; Groundwater Managment Cell, Irrigation Research Institute, Irrigation Department, Government of the Punjab: Lahore, Pakistan, 2013.

- Zakir-Hassan, G.; Shabir, G.; Yasmin, F.; Ghaffar, M.A. Environmental challenges for groundwater-irrigated agriculture in Punjab Pakistan. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Trends in Environmental Sustainability, Vehari, Pakistan, 21–23 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zakir-Hassan, G.; Punthakey, J.F.; Shabir, G.; Hassan, F.R. Assessing the potential of underground storage of flood water: A case study from Southern Punjab Region in Pakistan. J. Groundw. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakir-Hassan, G. Improving Sustainable Groundwater Management: A Case Study of Managed Aquifer Recharge in Punjab Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Agricultural, Environmental, and Veterinary Sciences, Bathurst, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IRI. Research Studies on Artificial Recharges of Aquifer in Punjab; Research Report No IRR-Phy/552; Irrigation Research Institute (IRI) Government of the Punjab, Irrigation Department: Lahore, Pakistan, 2009.

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association (APHA): Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 20th ed.; American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Groundwater Sampling: Operating Procedure; US-EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Solangi, G.S.; Siyal, A.A.; Babar, M.M.; Siyal, P. Evaluation of drinking water quality using the water quality index (WQI), the synthetic pollution index (SPI) and geospatial tools in Thatta district, Pakistan. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 160, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, H.; Farid, H.U.; Khan, Z.M.; Anjum, M.N.; Ahmad, I.; Chen, X.; Sakindar, P.; Mubeen, M.; Ahmad, M.; Gulakhmadov, A. An Integrated Use of GIS, Geostatistical and Map Overlay Techniques for Spatio-Temporal Variability Analysis of Groundwater Quality and Level in the Punjab Province of Pakistan, South Asia. Water 2020, 12, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, M.; Hassani, M.I.; Benhedid, H.; Brahim, A.H. Using GIS and Geostatistical Techniques for Mapping Piezometry and Groundwater Quality of the Albian Aquifer of the M’zab Region, Algerian Sahara. Int. J. Geosci. 2021, 12, 253–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setianto, A.; Triandini, T. Comparison of kriging and inverse distance weighted (IDW) interpolation methods in lineament extraction and analysis. J. SE Asian Appl. Geol. 2013, 5, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhi, A.; Biswal, S.K. Application of HPI (Heavy Metal Pollution Index) and Correlation Coefficient For The Assessment Of Ground Water Quality Near Ash Ponds Of Thermal Power Plants. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Adv. Technol. (IJSEAT) 2016, 4, 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Imran, M.; Murtaza, B.; Natasha; Arshad, M.; Nawaz, R.; Waheed, A.; Hammad, H.M.; Naeem, M.A.; Shahid, M.; et al. Hydrogeochemical and health risk investigation of potentially toxic elements in groundwater along River Sutlej floodplain in Punjab, Pakistan. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 5195–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishan, G.; Sudarsan, N.; Ghosh, N.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Sharma, A.; Mittal, S.; Sidhu, B.; Vashisth, R. Concentration of heavy metals in groundwater and heavy metal pollution index in Punjab. e-J. Geohydrology 2021, 2, 24–96. [Google Scholar]

- Elumalai, V.; Brindha, K.; Lakshmanan, E. Human Exposure Risk Assessment Due to Heavy Metals in Groundwater by Pollution Index and Multivariate Statistical Methods: A Case Study from South Africa. Water 2017, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapworth, D.J.; MacDonald, A.M.; Krishan, G.; Rao, M.S.; Gooddy, D.C.; Darling, W.G. Groundwater recharge and age-depth profiles of intensively exploited groundwater resources in northwest India. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 7554–7562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, V.M.; Panaskar, D.B.; Mukate, S.V.; Gaikwad, S.K.; Muley, A.A.; Varade, A.M. Health risk assessment of heavy metal contamination in groundwater of Kadava River Basin, Nashik, India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2018, 4, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjala, F.O.; Hashim, N.O.; Otwoma, D.; Nyambura, C.; Kebwaro, J.; Ndege, M.; Bartilol, S. Environmental assessment of heavy metal pollutants in soils and water from Ortum, Kenya. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Kim, H.; Jang, T. Irrigation Water Quality Standards for Indirect Wastewater Reuse in Agriculture: A Contribution toward Sustainable Wastewater Reuse in South Korea. Water 2016, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, M.A.; Aslam, A. Comparative Assessment of Pakistan National Drinking Water Quality Standards with Selected Asian Countries and World Health Organization; Policy Brief #60; Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI): Islamabad, Pakistan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Water Quality for Agriculture: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Irrigation and Drainage Papers. 2013. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/t0234e/t0234e00.htm (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- GoP_EPA. National Standards for Drinking Water Quality (NSDWG); Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency, Ministry of Environment, Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2008.

- Paz-Gonzalez, A.; Castro, M.T.T.; Vieira, S.R. Geostatistical analysis of heavy metals in a one-hectare plot under natural vegetation in a serpentine area. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2001, 81, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, G.Z.; Bhutta, M.N. A water balance model to estimate groundwater recharge in Rechna doab, Pakistan. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 1996, 10, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.S.; Sarwar, A. Managing salinity in the Indus Basin of Pakistan. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2009, 7, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.; Ahmad, M.Z. Groundwater and soil salinity variations in a canal command area in Pakistan. Irrig. Drain. 2009, 58, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, E. A holistic framework of water quality evaluation using water quality index (WQI) in the Yihe River (China). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 80937–80951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, I.B.; Nazzal, Y.; Howari, F.M.; Sharma, M.; Mogaraju, J.K.; Xavier, C.M. Geospatial Assessment of Groundwater Quality with the Distinctive Portrayal of Heavy Metals in the United Arab Emirates. Water 2022, 14, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thounaojam, T.C.; Panda, P.; Mazumdar, P.; Kumar, D.; Sharma, G.D.; Sahoo, L.; Sanjib, P. Excess copper induced oxidative stress and response of antioxidants in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 53, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, U.; Krishnakumar, A. Geospatial distribution of groundwater quality using entropy water quality index and statistical assessment: A study from a tropical climate river basin. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2021, 32, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Khalid, M.; Dumat, C.; Khalid, S.; Niazi, N.K.; Imran, M.; Bibi, I.; Ahmad, I.; Hammad, H.M.; Tabassum, R.A. Arsenic Level and Risk Assessment of Groundwater in Vehari, Punjab Province, Pakistan. Expo. Health 2017, 10, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.H.; Shahid, M.; Khalid, S.; Natasha; Shabbir, Z.; Bakhat, H.F.; Murtaza, B.; Farooq, A.; Akram, M.; Shah, G.M.; et al. Assessment of arsenic exposure by drinking well water and associated carcinogenic risk in peri-urban areas of Vehari, Pakistan. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Murtaza, B.; Shaheen, I.; Ahmad, I.; Ullah, M.I.; Abbas, T.; Rehman, F.; Ashraf, M.R.; Khalid, S.; Abbas, S.; et al. Assessment and public perception of drinking water quality and safety in district Vehari, Punjab, Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, U.C.; Gupta, S.C. Trace element toxicity relationships to crop production and livestock and human health: Implications for management. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2008, 29, 1491–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Lata, R.; Thakur, N.; Bajala, V.; Kuniyal, J.C.; Kumar, K. Application of Multivariate Statistical Analysis and Water Quality Index for Quality Characterization of Parbati River, Northwestern Himalaya, India. Discov. Water 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, L.; Ahmad, N.; Arshad, M.; Ahmad, R. Effect of Different Irrigation and Management Practices on Corn Growth Parameters. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci. 2014, 12, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.V.; Mathew, S.; Swaminathan, G. Multifactorial Fuzzy Approach for the Assessment of Groundwater Quality. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2010, 2, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Singh, S.; Parihar, P.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Heavy Metal Tolerance in Plants: Role of Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics, and Ionomics. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaza, B.; Natasha; Amjad, M.; Shahid, M.; Imran, M.; Shah, N.S.; Abbas, G.; Naeem, M.A.; Amjad, M. Compositional and health risk assessment of drinking water from health facilities of District Vehari, Pakistan. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Statistical Parameter | Al | As | Ba | Cd | Co | Cr | Cu | Mn | Mo | Ni | Pb | Se | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of samples (n) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Min | 5.76 | 14.62 | 33.79 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 15.10 | 1.92 | 0.58 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| Max | 2463.75 | 166.84 | 202.69 | 0.03 | 1.77 | 6.17 | 25.88 | 261.68 | 26.92 | 7.61 | 5.36 | 11.81 | 205.50 |

| Standard Error | 150.26 | 9.71 | 10.14 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 1.41 | 14.84 | 1.29 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.87 | 14.38 |

| Mean | 334.83 | 55.84 | 84.60 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 2.07 | 3.74 | 94.16 | 6.80 | 2.04 | 1.55 | 1.68 | 45.30 |

| Limits for drinking | 200 | 50 | 1300 | 3 | 50 | 50 | 2000 | 50 | 10 | 70 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Limits for irrigation | 5000 | 100 | - | 10 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 200 | 10 | 200 | 65 | 20 | 2000 |

| Al | As | Ba | Cd | Co | Cr | Cu | Mn | Mo | Ni | Pb | Se | Zn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 1 | ||||||||||||

| As | −0.28 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Ba | 0.695 ** | −0.15 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Cd | b | b | b | b | |||||||||

| Co | −0.09 | −0.474 * | −0.07 | b | 1 | ||||||||

| Cr | 0.977 ** | −0.29 | 0.662 ** | b | −0.12 | 1 | |||||||

| Cu | 0.26 | −0.24 | 0.28 | b | −0.15 | 0.28 | 1 | ||||||

| Mn | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.33 | b | −0.470 * | 0.31 | 0.27 | 1 | |||||

| Mo | −0.31 | −0.14 | −0.39 | b | 0.16 | −0.31 | −0.28 | −0.34 | 1 | ||||

| Ni | 0.975 ** | −0.28 | 0.657 ** | b | −0.08 | 0.968 ** | 0.30 | 0.35 | −0.42 | 1 | |||

| Pb | 0.635 ** | −0.20 | 0.615 ** | b | −0.12 | 0.611 ** | 0.17 | 0.16 | −0.24 | 0.689 ** | 1 | ||

| Se | −0.17 | −0.07 | 0.06 | b | −0.26 | −0.20 | 0.43 | 0.40 | −0.12 | −0.19 | −0.33 | 1 | |

| Zn | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.19 | b | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.19 | 0.17 | −0.24 | −0.03 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Name of Heavy Metal | Maximum Permissible Limits for Irrigation Water (ppb) [74] | Fit | Unfit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Samples | % | No. of Samples | % | ||

| Aluminum (Al) | 5000 | 20 | 100% | - | - |

| Arsenic (As) | 100 | 17 | 85% | 3 | 15% |

| Cadmium (Cd) | 10 | 20 | 100% | - | - |

| Cobalt (Co) | 50 | 20 | 100% | - | - |

| Chromium (Cr) | 100 | 20 | 100% | - | - |

| Copper (Cu) | 200 | 20 | 100% | - | - |

| Manganese (Mn) | 200 | 18 | 90% | 2 | 10% |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 10 | 17 | 85% | 3 | 15% |

| Nickel (Ni) | 200 | 20 | 100% | - | - |

| Lead (Pb) | 65 | 20 | 100% | - | - |

| Selenium (Se) | 20 | 20 | 100% | - | - |

| Zinc (Zn) | 2000 | 20 | 100% | - | - |

| Heavy Metal | WHO Maximum Permissible Limits for Drinking Water (ppb) | Fit | Unfit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Samples | % | No. of Samples | % | ||

| Aluminum (Al) | 200 | 14 | 70 | 6 | 30 |

| Arsenic (As) | 50 | 12 | 60 | 8 | 40 |

| Barium (Ba) | 1300 | - | - | - | - |

| Cadmium (Cd) | 3 | 20 | 100 | - | - |

| Cobalt (Co) | 50 | 20 | 100 | - | - |

| Chromium (Cr) | 50 | 20 | 100 | - | - |

| Copper (Cu) | 2000 | 20 | 100 | - | - |

| Manganese (Mn) | 50 | 6 | 30 | 14 | 70 |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 10 | 17 | 85 | 3 | 15 |

| Nickel (Ni) | 70 | 20 | 100 | - | - |

| Lead (Pb) | 10 | 20 | 100 | - | - |

| Selenium (Se) | 10 | 18 | 90 | 2 | 10 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 20 | 12 | 60 | 8 | 40 |

| (HPI) Range | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Type of Water | No. of Sample | % Sample | |

| 1 | <25 | Excellent | 1 (HM15) | 5 |

| 2 | 26–50 | Good | 4 | 20 |

| 3 | 51–75 | Poor | 7 | 35 |

| 4 | 76–100 | Very Poor | 3 (HM5, HM6, HM19) | 15 |

| 5 | >100 | Unsuitable | 5 | 25 |

| Heavy Metal Index (HI) | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Value | Classification | No of Samples | % Samples |

| 1 | <0.3 | Very Pure | - | |

| 2 | 0.3–1.0 | Pure | - | |

| 3 | 1.0–2.0 | Slightly Affected | - | |

| 4 | 2.0–4.0 | Moderately Affected | 4 | 20 |

| 5 | 4.0–6.0 | Strongly Affected | 4 | 20 |

| 6 | >6 | Seriously Affected | 12 | 60 |

| Sample No. | Type of Water | HPI | HI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Class | Value | Class | ||

| HM (Avg1–20) | Avg of 20 GW samples | 82.226 | Very Poor | 10.434 | Seriously Affected |

| HM21 | Drain | 75.504 | Very Poor | 6.018 | Seriously Affected |

| HM22 | Canal | 67.777 | Poor | 8.423 | Seriously Affected |

| HM23 | River | 70.694 | Poor | 6.283 | Seriously Affected |

| Heavy Metal | Maximum Permissible Limits for Drinking Water (ppb) | Canal | River | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (ppb) | Remarks | Value | Remarks | ||

| Al | 200 | 22.03 | Fit | 213.57 | Unfit |

| As | 50 | 31.38 | Fit | 9.36 | Fit |

| Ba | 1300 | 71.05 | Fit | 52.57 | - |

| Cd | 3 | 0.03 | Fit | 0.03 | Fit |

| Co | 50 | 2.07 | Fit | 0.44 | Fit |

| Cr | 50 | 0.96 | Fit | 2.05 | Fit |

| Cu | 2000 | 1.09 | Fit | 3.13 | Fit |

| Mn | 50 | 138 | unfit | 16.83 | Fit |

| Mo | 10 | 2.33 | Fit | 2.87 | Fit |

| Ni | 70 | 2.31 | Fit | 2.08 | Fit |

| Pb | 10 | 0.25 | Fit | 0.25 | Fit |

| Se | 40 | 0.1 | Fit | 9.1 | Fit |

| Zn | 3000 | 0.03 | Fit | 9.49 | Fit |

| Heavy Metal Index (HI) | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Value | Remarks | No. of Samples | % of Samples |

| 1 | <0.3 | Very Pure | - | |

| 2 | 0.3–1.0 | Pure | - | |

| 3 | 1.0–2.0 | Slightly Affected | - | |

| 4 | 2.0–4.0 | Moderately Affected | 4 | 20 |

| 5 | 4.0–6.0 | Strongly Affected | 4 | 20 |

| 6 | >6 | Seriously Affected | 12 | 60 |

| Sample No. | Type of Water | HPI | HI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Class | Value | Class | ||

| HM (Avg; n = 20) | Avg GW | 82.23 | Very Poor | 10.43 | Seriously Affected |

| HM21 | Drain | 75.50 | Very Poor | 6.02 | Seriously Affected |

| HM22 | Canal | 67.78 | Poor | 8.42 | Seriously Affected |

| HM23 | River | 70.69 | Poor | 6.28 | Seriously Affected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zakir-Hassan, G.; Baumgartner, L.; Allan, C.; Punthakey, J.F.; Rasheed, H. Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Groundwater for a Managed Aquifer Recharge Project. Water 2025, 17, 3092. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213092

Zakir-Hassan G, Baumgartner L, Allan C, Punthakey JF, Rasheed H. Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Groundwater for a Managed Aquifer Recharge Project. Water. 2025; 17(21):3092. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213092

Chicago/Turabian StyleZakir-Hassan, Ghulam, Lee Baumgartner, Catherine Allan, Jehangir F. Punthakey, and Hifza Rasheed. 2025. "Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Groundwater for a Managed Aquifer Recharge Project" Water 17, no. 21: 3092. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213092

APA StyleZakir-Hassan, G., Baumgartner, L., Allan, C., Punthakey, J. F., & Rasheed, H. (2025). Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Groundwater for a Managed Aquifer Recharge Project. Water, 17(21), 3092. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213092