Validation of Sea Level Anomalies from the SWOT Altimetry Mission Around the Coastal Regions of East Asia and the US West Coast

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Areas

2.1. The Coastal Region of East Asia

2.2. The US West Coast

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Datasets

3.1.1. Sentinel-3A Data

3.1.2. ICESat-2 Data

3.1.3. SWOT Data

3.1.4. Tide Gauge Data

3.2. Altimeter SLA

3.3. Tide Gauge SLA

3.4. Validation of Altimeter Data Using Tide Gauge Data

3.5. Triple Collocation Functional Relationship (FR) Model

4. Results

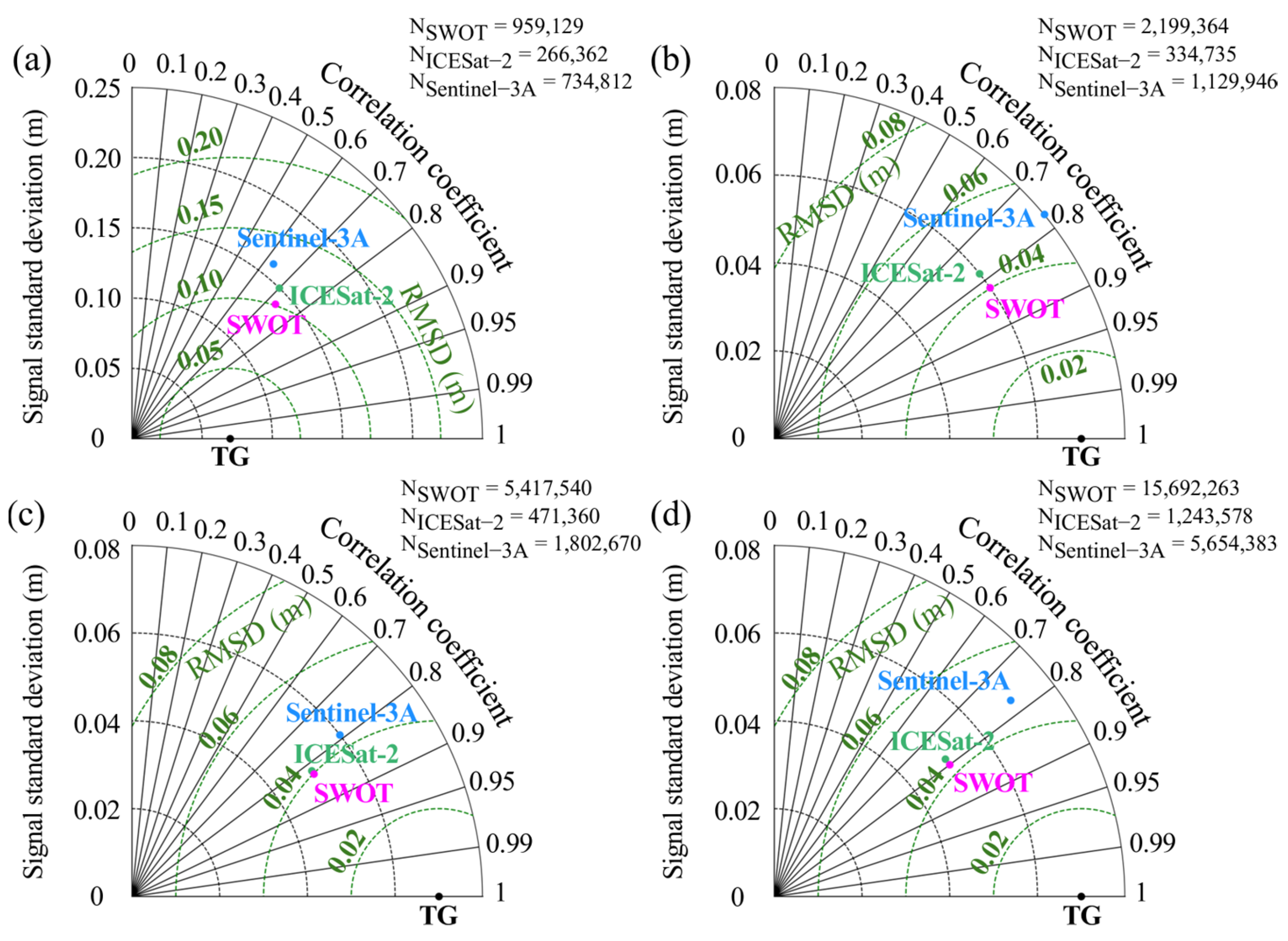

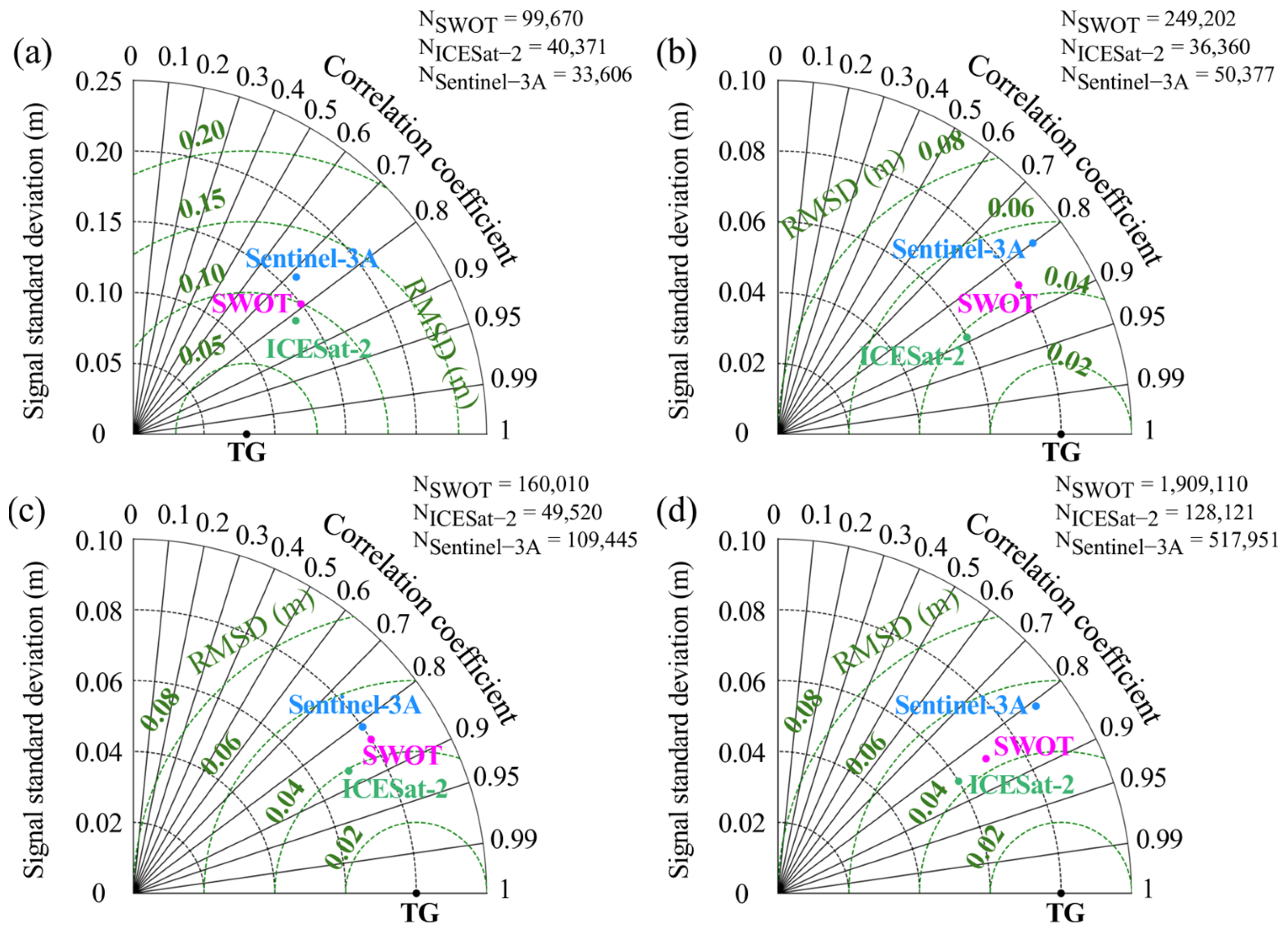

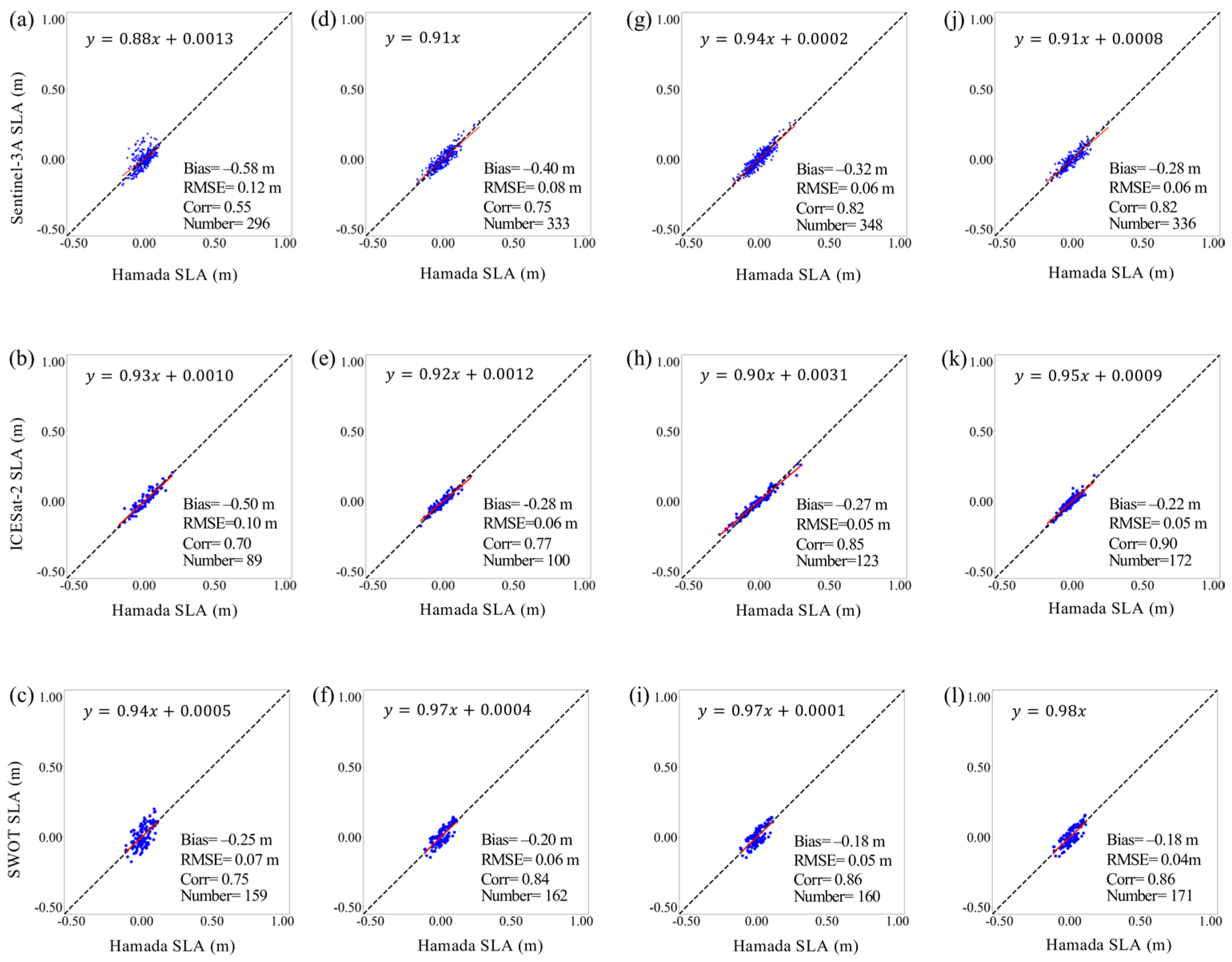

4.1. Comparison of Altimeter SLA Estimates Against Tide Gauge Measurements

4.2. Evaluation of Altimeter and Tide Gauge Errors Using the Triple Collocation FR Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Melet, A.; Almar, R.; Hemer, M.; Le Cozannet, G.; Meyssignac, B.; Ruggiero, P. Contribution of Wave Setup to Projected Coastal Sea Level Changes. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2020, 125, e2020JC016078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazenave, A.; Gouzenes, Y.; Birol, F.; Leger, F.; Passaro, M.; Calafat, F.M.; Shaw, A.; Nino, F.; Legeais, J.F.; Oelsmann, J.; et al. Sea Level along the World’s Coastlines Can Be Measured by a Network of Virtual Altimetry Stations. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M.; Tsontos, V. Satellite Altimetry for Ocean and Coastal Applications: A Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birgiel, E.; Ellmann, A.; Delpeche-Ellmann, N. Examining the Performance of the Sentinel-3 Coastal Altimetry in the Baltic Sea Using a Regional High-Resolution Geoid Model. In Proceedings of the 2018 Baltic Geodetic Congress (BGC Geomatics), Olsztyn, Poland, 21–23 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- An, Z.; Chen, P.; Tang, F.; Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z. Evaluating the Performance of Seven Ongoing Satellite Altimetry Missions for Measuring Inland Water Levels of the Great Lakes. Sensors 2022, 22, 9718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinogradov, S.V.; Ponte, R.M. Annual Cycle in Coastal Sea Level from Tide Gauges and Altimetry. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2010, 115, 2009JC005767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Rodríguez, J.; Trasviña-Castro, A. Sea Level Anomaly Measurements from Satellite Coastal Altimetry and Tide Gauges at the Entrance of the Gulf of California. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 1593–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lin, L.; Fan, L.; Liu, N.; Huang, L.; Xu, Y.; Mertikas, S.P.; Jia, Y.; Lin, M. Satellite Altimetry: Achievements and Future Trends by a Scientometrics Analysis. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, E.; Fernandes, M.; Lázaro, C. Assessment of Altimetric Range and Geophysical Corrections and Mean Sea Surface Models—Impacts on Sea Level Variability around the Indonesian Seas. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.; Lázaro, C. GPD+ Wet Tropospheric Corrections for CryoSat-2 and GFO Altimetry Missions. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlon, C.; Berruti, B.; Buongiorno, A.; Ferreira, M.-H.; Féménias, P.; Frerick, J.; Goryl, P.; Klein, U.; Laur, H.; Mavrocordatos, C.; et al. The Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES) Sentinel-3 Mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESA, S3 Altimetry Instruments. 2025. Available online: https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/web/s3-altimetry-instruments (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Mostafavi, M.; Delpeche-Ellmann, N.; Ellmann, A. Accurate Sea Surface Heights from Sentinel-3A and Jason-3 Retrackers by Incorporating High-Resolution Marine Geoid and Hydrodynamic Models. J. Geod. Sci. 2021, 11, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Ferreira, A.M.; Da Silva, J.C.B.; Magalhaes, J.M. SAR Mode Altimetry Observations of Internal Solitary Waves in the Tropical Ocean Part 1: Case Studies. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Y.; Fan, C.; Cui, W. Validation of Sentinel-3A/3B and Jason-3 Altimeter Wind Speeds and Significant Wave Heights Using Buoy and ASCAT Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Deng, X. Validation of Sentinel-3A SAR Mode Sea Level Anomalies around the Australian Coastal Region. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, T.; Brenner, A.; Hancock, D.; Robins, J.; Saba, J.; Harbeck, K.; Gibbons, A.; Lee, J.; Luthcke, S.; Rebold, T. Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat-2) Project Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document (ATBD) for Global Geolocated Photons ATL03, Version 6; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzanga, B.; Heijkoop, E.; Hamlington, B.D.; Nerem, R.S.; Gardner, A. An Assessment of Regional ICESat-2 Sea-level Trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL092327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, M.; Baltazar Andersen, O. ICESat-2 for Coastal MSS Determination—Evaluation in the Norwegian Coastal Zone. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, T.A.; Martino, A.J.; Markus, T.; Bae, S.; Bock, M.R.; Brenner, A.C.; Brunt, K.M.; Cavanaugh, J.; Fernandes, S.T.; Hancock, D.W.; et al. The Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite—2 Mission: A Global Geolocated Photon Product Derived from the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 233, 111325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Pavelsky, T.; Cretaux, J.; Morrow, R.; Farrar, J.T.; Vaze, P.; Sengenes, P.; Vinogradova-Shiffer, N.; Sylvestre-Baron, A.; Picot, N.; et al. The Surface Water and Ocean Topography Mission: A Breakthrough in Radar Remote Sensing of the Ocean and Land Surface Water. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL107652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peral, E.; Esteban-Fernández, D.; Rodríguez, E.; McWatters, D.; De Bleser, J.-W.; Ahmed, R.; Chen, A.C.; Slimko, E.; Somawardhana, R.; Knarr, K.; et al. KaRIn, the Ka-Band Radar Interferometer of the SWOT Mission: Design and in-Flight Performance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5214127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignudelli, S.; Birol, F.; Benveniste, J.; Fu, L.-L.; Picot, N.; Raynal, M.; Roinard, H. Satellite Altimetry Measurements of Sea Level in the Coastal Zone. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 1319–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montillet, J.-P.; Melbourne, T.I.; Szeliga, W.M. GPS Vertical Land Motion Corrections to Sea-level Rise Estimates in the Pacific Northwest. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2018, 123, 1196–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Ling, T.; Feng, L. The Influence of ENSO on Sea Surface Temperature Variations in the China Seas. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2013, 32, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zong, H.; Cheng, Y. Interannual Sea Level Variability in the South China Sea and Its Response to ENSO. Global Planet. Change 2007, 55, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, D.; Wang, T.; Liu, Q.; Deng, L.; Zhao, L. Acceleration of the Extreme Sea Level Rise along the Chinese Coast. Earth Space Sci. 2019, 6, 1942–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drogoul, A.; Pannier, E.; Nguyen, M.-H.; Woillez, M.-N.; Ngo-Duc, T.; Espagne, É. Climate Change in Vietnam: Impacts and Adaptation. Available online: http://theconversation.com/climate-change-in-vietnam-impacts-and-adaptation-173462 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Nakano, H.; Urakawa, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Toyoda, T.; Kawakami, Y.; Yamanaka, G. Long-Term Sea-Level Variability along the Coast of Japan during the 20th century revealed by a 1/10° OGCM. J. Oceanogr. 2023, 79, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietbroek, R.; Brunnabend, S.-E.; Kusche, J.; Schröter, J.; Dahle, C. Revisiting the Contemporary Sea-Level Budget on Global and Regional Scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1504–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; García-Medina, G.; Wu, W.-C.; Wang, T. Characteristics and Variability of the Nearshore Wave Resource on the U.S. West Coast. Energy 2020, 203, 117818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouakhi, A.; Villarini, G.; Zhang, W.; Slater, L.J. Seasonal Predictability of High Sea Level Frequency Using ENSO Patterns along the U.S. West Coast. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 131, 103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sella, G.F.; Stein, S.; Dixon, T.H.; Craymer, M.; James, T.S.; Mazzotti, S.; Dokka, R.K. Observation of Glacial Isostatic Adjustment in “Stable” North America with GPS. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 2006GL027081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.-H.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Lin, L.-C.; Kao, H.-C. Annual Sea Level Amplitude Analysis over the North Pacific Ocean Coast by Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition Method. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.J.; Lázaro, C.; Vieira, T. On the Role of the Troposphere in Satellite Altimetry. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morison, J.; Hancock, D.; Dickinson, S.; Robbins, J.; Roberts, L.; Kwok, R.; Palm, S.; Smith, B.; Jasinski, M.; Plant, B.; et al. Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat-2) Project Algortihm Theorectical Basis Document (ATBD) for Ocean Surface Height, Version 6; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory. SWOT Science Data Products User Handbook, JPL D-109532; Jet Propulsion Laboratory: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Laloue, A.; Schaeffer, P.; Pujol, M.-I.; Veillard, P.; Andersen, O.; Sandwell, D.; Delepoulle, A.; Dibarboure, G.; Faugère, Y. Merging Recent Mean Sea Surface into a 2023 Hybrid Model (from Scripps, DTU, CLS, and CNES). Earth Space Sci. 2025, 12, e2024EA003836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, D.E.; Tayler, R.J. New Computations of the Tide-Generating Potential. Geophys. J. R. Astron. Soc. 1971, 23, 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, D.E.; Edden, A.C. Corrected Tables of Tidal Harmonics. Geophys. J. Int. 1973, 33, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, G.; Luzum, B. (Eds.) IERS Conventions (2010); IERS Technical Note No. 36; Verlag des Bundesamts für Kartographie und Geodäsie: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wahr, J.M. Deformation Induced by Polar Motion. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1985, 90, 9363–9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Wahr, J.; Beckley, B. Revisiting the Pole Tide for and from Satellite Altimetry. J. Geod. 2015, 89, 1233–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sea Level Station Monitoring Facility. Available online: http://www.iocsealevelmonitoring.org/service.php (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Codiga, D.L. Unified Tidal Analysis and Prediction Using the UTide Matlab Functions; Technical Report 2011-01; Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island: Narragansett, RI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, S.; Sterl, A. Validation of Ocean Wind and Wave Data Using Triple Collocation. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2003, 108, 2002JC001491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tréboutte, A.; Carli, E.; Ballarotta, M.; Carpentier, B.; Faugère, Y.; Dibarboure, G. KaRIn Noise Reduction Using a Convolutional Neural Network for the SWOT Ocean Products. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, M.; Breili, K.; Gerlach, C.; Ophaug, V. Validation of Retracked Sentinel-3 Altimetry Observations along the Norwegian Coast. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 4067–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mission | Reference Ellipsoid | Time Period | Repeat Cycles | Altimeter | Inclination | Sampling Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentinel-3A | WGS84 | Oct 2018– Dec 2024 | ~27 days | SRAL | 98.65 | ~330 m |

| ICESat-2 | WGS84 | Oct 2018–Nov 2024 | ~91 days | ATLAS | 92 | 70 m–7 km |

| SWOT | WGS84 | Jul 2023– Dec 2024 | ~21 days | KaRIn | 77.6 | 2 × 2 km |

| Tide Gauge | Country | Location | Time Period | Missing Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lon | Lat | ||||

| Vung Tau | Vietnam | 107.1 E | 10.3 N | Oct 2018–Mar 2023 | 9.20 |

| Quarry Bay | China | 114.2 E | 22.3 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.31 |

| Currimao | Philippines | 120.5 E | 18.0 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 16.42 |

| Ishigaki | Japan | 124.2 E | 24.3 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.28 |

| Manila | Philippines | 121.0 E | 14.6 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 6.84 |

| Bitung | Indonesia | 125.2 E | 1.4 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 12.77 |

| Nagasaki | Japan | 130.0 E | 32.7 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.35 |

| Nakano Sima | Japan | 129.9 E | 29.8 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 8.95 |

| Naze | Japan | 129.5 E | 28.4 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 9.00 |

| Hamada | Japan | 132.1 E | 34.9 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.31 |

| Aburatsu | Japan | 131.4 E | 31.6 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.35 |

| Nishinoomote | Japan | 131.0 E | 30.7 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 9.60 |

| Toyama | Japan | 137.2 E | 36.8 N | Oct 2018–Mar 2023 | 0.10 |

| Maisaka | Japan | 137.6 E | 34.7 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.31 |

| Kushimoto | Japan | 135.8 E | 33.5 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.30 |

| Yakutat | USA | 139.7 W | 59.5 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 1.98 |

| Sitka | USA | 135.3 W | 57.1 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.25 |

| Ketchikan | USA | 131.6 W | 55.3 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.18 |

| Tofino | Canada | 125.9 W | 49.2 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.03 |

| Bamfield | Canada | 125.1 W | 48.8 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.03 |

| Neah Bay | USA | 124.6 W | 48.4 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.48 |

| South Beach | USA | 124.0 W | 44.6 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 3.93 |

| Crescent | USA | 124.2 W | 41.7 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.09 |

| San Francisco | USA | 122.5 W | 37.8 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 2.07 |

| La Jolla | USA | 117.3 W | 32.9 N | Oct 2018–Dec 2024 | 0.14 |

| Mission | Sentinel-3A | ICESat-2 | SWOT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry tropospheric correction | ECMWF | NASA GMAO GEOS-5 | ECMWF |

| Wet tropospheric correction | GPD+ | NASA GMAO GEOS-5 | ECMWF |

| Ionospheric correction | GIM | NASA GMAO GEOS-5 | GIM |

| Dynamic atmospheric correction | MOG2D | MOG2D | MOG2D |

| Geocentric ocean tide correction | FES2022 | FES2022 | FES2022 |

| Solid Earth tide | Cartwright and Tayler (1971) [39]; Cartwright and Edden (1973) [40] | IERS Conventions (2010) [41] | Cartwright and Tayler (1971) [39] Cartwright and Edden (1973) [40] |

| Pole tide | Wahr (1985) [42] | IERS Conventions (2010) [41] | Desai, Wahr, and Beckley (2015) [43] |

| Mean sea surface | 2023 Hybrid [38] | 2023 Hybrid [38] | 2023 Hybrid [38] |

| TG | 0–5 km | 5–10 km | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (m) | Corr | Number | RMSE (m) | Corr | Number | |

| Aburatsu | 0.06 | 0.74 | 89 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 97 |

| Bitung | 0.05 | 0.70 | 65 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 81 |

| Currimao | 0.08 | 0.65 | 58 | 0.06 | 0.78 | 63 |

| Hamada | 0.07 | 0.75 | 159 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 162 |

| Ishigaki | 0.06 | 0.76 | 84 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 113 |

| Kushimot | 0.07 | 0.72 | 108 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 114 |

| Maisaka | 0.06 | 0.76 | 108 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 124 |

| Manila | 0.07 | 0.70 | 67 | 0.05 | 0.78 | 68 |

| Nagasaki | 0.06 | 0.72 | 88 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 105 |

| Nakano | 0.06 | 0.73 | 87 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 116 |

| Naze | 0.07 | 0.68 | 72 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 103 |

| Nishinoo | 0.07 | 0.71 | 78 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 88 |

| QuarryBay | 0.06 | 0.82 | 106 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 110 |

| TG | 0–5 km | 5–10 km | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (m) | Corr | Number | RMSE (m) | Corr | Number | |

| Yakutat | 0.07 | 0.75 | 91 | 0.05 | 0.92 | 201 |

| Sitka | 0.07 | 0.84 | 303 | 0.06 | 0.87 | 300 |

| Ketchika | 0.08 | 0.78 | 306 | 0.06 | 0.85 | 310 |

| Tofino | 0.06 | 0.83 | 230 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 236 |

| Bamfield | 0.07 | 0.79 | 195 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 228 |

| Neah Bay | 0.06 | 0.82 | 207 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 200 |

| South Beach | 0.05 | 0.75 | 93 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 109 |

| Crescent | 0.08 | 0.67 | 155 | 0.07 | 0.72 | 179 |

| San Francisco | 0.06 | 0.83 | 144 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 181 |

| La Jolla | 0.05 | 0.85 | 137 | 0.04 | 0.90 | 176 |

| Datasets (x, y, z) | n | <x> (m) | (m2) | (m2) | (m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S3A, SWOT and TG | 231 | −0.57 | 0.019 (0.016, 0.023) | 0.010 (0.009, 0.010) | 0.005 (0.004, 0.005) |

| S3A, SWOT and IS2 | 298 | −0.66 | 0.016 (0.015, 0.020) | 0.009 (0.008, 0.010) | 0.012 (0.009, 0.014) |

| S3A, IS2 and TG | 331 | −0.60 | 0.016 (0.012, 0.019) | 0.012 (0.011, 0.013) | 0.007 (0.006, 0.007) |

| SWOT, IS2 and TG | 173 | −0.59 | 0.009 (0.007, 0.011) | 0.014 (0.012, 0.016) | 0.006 (0.006, 0.006) |

| Datasets (x, y, z) | n | <x> (m) | (m2) | (m2) | (m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S3A, SWOT and TG | 148 | −0.66 | 0.015 (0.013, 0.017) | 0.010 (0.008, 0.012) | 0.007 (0.006, 0.008) |

| S3A, SWOT and IS2 | 232 | −0.64 | 0.017 (0.014, 0.020) | 0.007 (0.005, 0.009) | 0.007 (0.005, 0.008) |

| S3A, IS2 and TG | 169 | −0.73 | 0.015 (0.012, 0.018) | 0.007 (0.005, 0.008) | 0.004 (0.003, 0.005) |

| SWOT, IS2 and TG | 169 | −0.61 | 0.009 (0.006, 0.011) | 0.006 (0.005, 0.007) | 0.004 (0.002, 0.004) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, H.; Peng, F.; Shen, Y. Validation of Sea Level Anomalies from the SWOT Altimetry Mission Around the Coastal Regions of East Asia and the US West Coast. Water 2025, 17, 3066. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213066

Zhu H, Peng F, Shen Y. Validation of Sea Level Anomalies from the SWOT Altimetry Mission Around the Coastal Regions of East Asia and the US West Coast. Water. 2025; 17(21):3066. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213066

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Haojie, Fukai Peng, and Yunzhong Shen. 2025. "Validation of Sea Level Anomalies from the SWOT Altimetry Mission Around the Coastal Regions of East Asia and the US West Coast" Water 17, no. 21: 3066. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213066

APA StyleZhu, H., Peng, F., & Shen, Y. (2025). Validation of Sea Level Anomalies from the SWOT Altimetry Mission Around the Coastal Regions of East Asia and the US West Coast. Water, 17(21), 3066. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213066