1. Introduction

South America is a region richly endowed with water resources, largely due to its vast network of shared river basins, such as the Amazon and La Plata. The Paraná River, located in the La Plata basin [

1], is not only one of South America’s major rivers, but is also a global leader in hydroelectric development. This river hosts numerous projects, including binational hydropower plants, and its international stretch still holds considerable untapped potential [

2]. Indeed, a significant portion of the basin’s installed capacity, amounting to 17,200 MW, is in these international stretches shared by Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, extending from the site of now-submerged Salto del Guairá (Guairá Falls) to the confluence of the Paraná and Paraguay Rivers [

3].

The development of the Paraná basin’s hydraulic potential has faced challenges at both national and international levels [

1,

4]. Environmental issues, for instance, have posed obstacles to reaching a consensus on the management of the Paraná River’s natural resources [

1,

4]. This problem is not unique to the region; many countries worldwide face the challenge of managing shared rivers [

5,

6]. Such was the case for Paraguay and its two neighbors, with whom dialog was often complex. As a country with a relatively smaller economy, Paraguay negotiates from an asymmetrical position toward its more economically and politically influential neighbors Argentina and Brazil. Therefore, reaching both internal and external consensus on the management of shared natural resources, which is crucial for development (the hydro-energy resources shared by Paraguay in the Paraná River are the main ones the country has; the participation of exclusive national hydro-energy resources is not relevant compared to shared resources, according to the Latin America and Caribbean Energy Information System (available at

https://sielac.olade.org/), which has been a significant challenge), has posed a significant challenge. Nonetheless, not only were the parties involved parties successful in establishing bilateral agreements, but were also successful in concluding a tripartite agreement with the country located along the downstream continuation of the river system.

These discussions transcended mere energy production, encompassing the distribution of benefits from hydroelectric projects and economic transparency among participating countries [

7]. However, previous negotiations have led to dissatisfaction within various segments of Paraguayan society, sparking controversies over equity in benefit distribution, transparency in decision-making processes, and the management of financial and contractual resources [

4,

8,

9,

10]. The complexity of calculating the distribution of hydroelectric rents from shared resources is highlighted by [

11]. The ITAIPU hydroelectric plant, a result of bilateral negotiations between Paraguay and Brazil and operational since 1984, has been the subject of multiple subsequent negotiations to address financial issues related to both construction debt repayment and economic benefit distribution [

4,

8,

9,

10].

The objective of this research is to identify the strategies implemented in international negotiations that enabled agreements on the governance of shared natural resources for hydropower exploitation, thereby facilitating the design, construction, and operation of the binational hydropower plants ITAIPU (Brazil-Paraguay) and YACYRETA (Argentina-Paraguay). Although this study focuses on analyzing past events, its findings are of significant interest for advancing energy integration in the La Plata basin, where future projects exist to exploit shared hydraulic potential in the Paraná and Uruguay rivers [

3].

This study contributes primarily to reflections and preparations for current and future bilateral negotiations concerning governance, energy trade management, and equitable benefit distribution. The review of Annex C of the ITAIPU treaty, initially scheduled for 2023 according to the 1973 bilateral instrument, is a primary reason for focusing this analysis on this case. Thus, this analysis centers on ITAIPU’s bilateral negotiation process, while remaining mindful of the complex negotiating environment among the three countries sharing international sections of the watercourse. The results can aid in advancing regional energy integration by informing strategies for future negotiations, whether for the revision of ITAIPU’s Annex C or other international negotiations on shared basins.

This study focuses on the systematization of the lessons learned in the negotiation process of a particular case of the construction of governance over a natural resource shared between two countries and its energy use. However, it is worth mentioning that there are other cases of shared water resource management in the world: for instance, we can cite, for context, the case of the Nile River basin [

12]; or studies that analyze the negotiations between two countries with asymmetric economies (in size, as is the case of ITAIPU), such as Lesotho and South Africa, in the management of resources for a multipurpose project (Lesotho Highlands Water Project): water supply and hydroelectricity production [

13].

The empirical contribution of this work lies in adding original and unique primary data through a database of interviews with key actors directly involved in the historical negotiation processes. Additionally, it offers a novel application of the “learning history” methodology to a binational entity harnessing a shared natural resource for energy generation, thereby enabling the understanding and systematization of these experiences. Furthermore, it contributes to the field of knowledge management by applying the Deming cycle to analyze the lessons learned from an international negotiation process (some academic work aims to extend the use of continuous improvement cycle-based analysis to diverse areas of research; see, for example, [

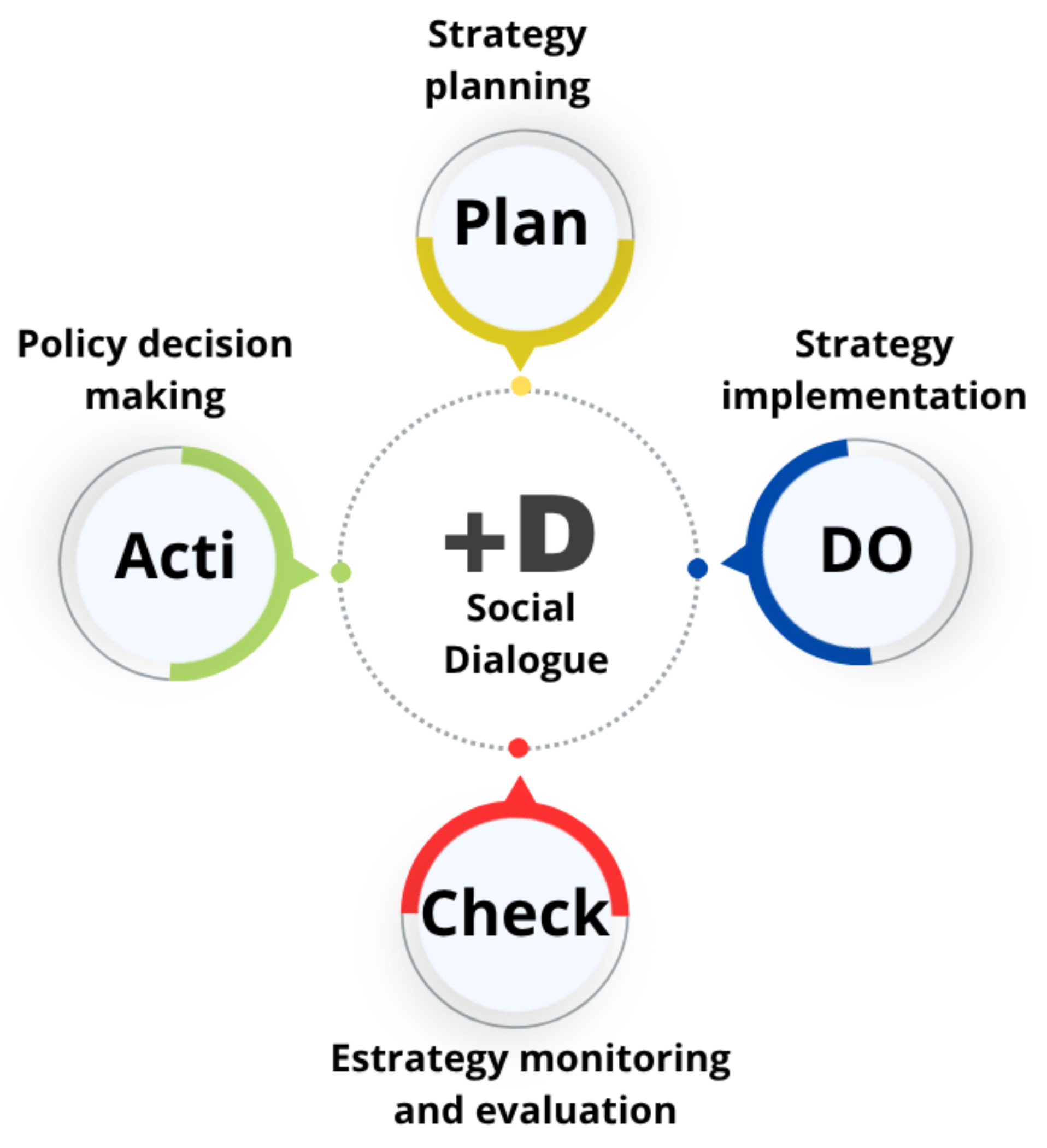

14]) to process, organize, and plan strategies for future negotiations based on a continuous improvement system. Moreover, the conclusions may have direct policy implications by proposing a design for the internal organization of the pre-negotiation preparation process at the country level.

This research focuses on the different stages of the negotiation process for ITAIPU’s construction and operation, seeking to understand how this was organized. The analysis is framed by the perspectives of historical academics and negotiation study references such as Cross (1977) and Paterson (1982): for the former, negotiations had a cyclical and dynamic character in permanent development; for the latter, the negotiation process can be understood as a learning process [

15,

16].

This paper is organized into six sections.

Section 2 presents a summary of the analysis of the history of economic development and natural resource governance, also reviewing analytical frameworks that approach negotiation as a dynamic process.

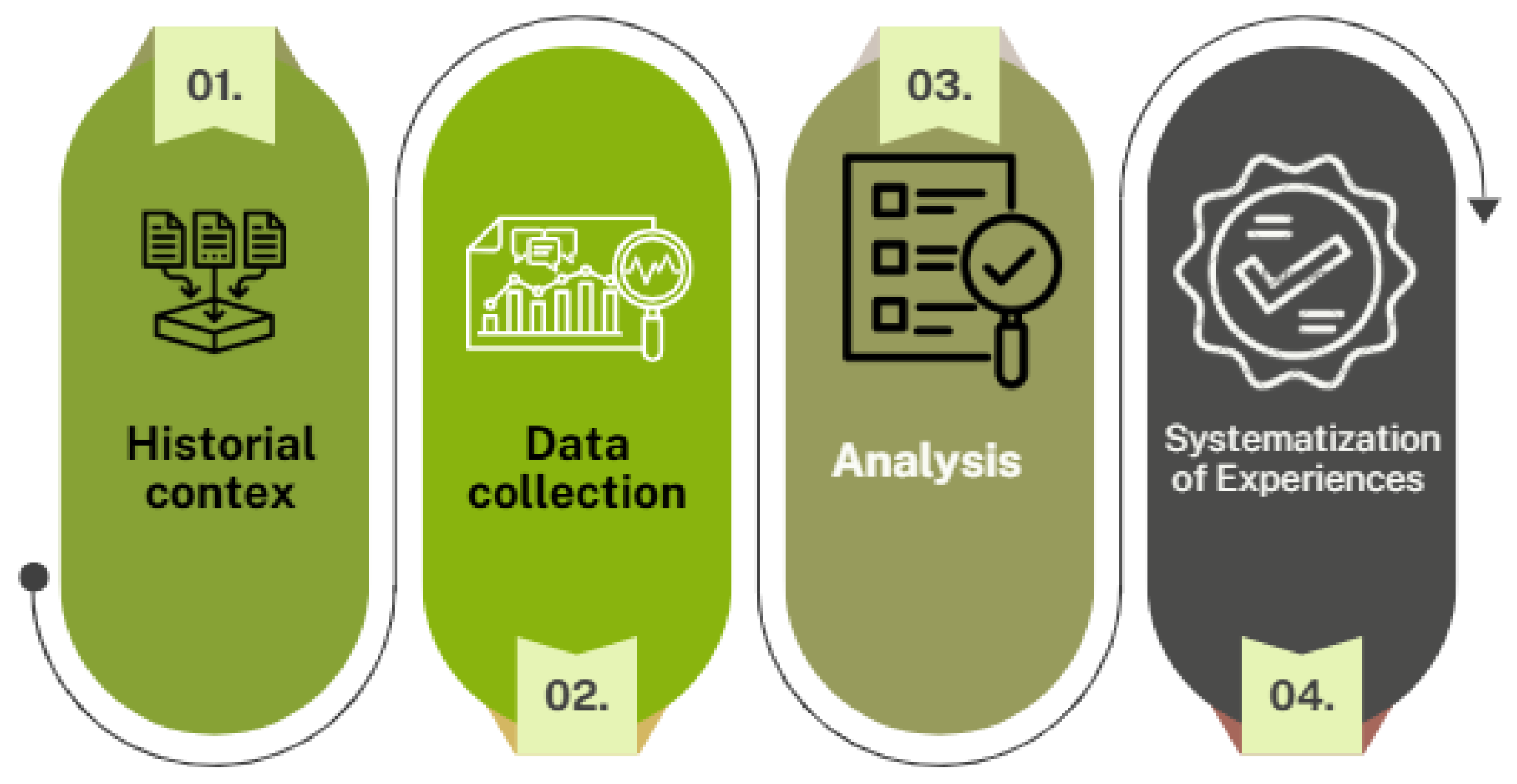

Section 3 explains the methodological aspects, particularly those related to data collection.

Section 4 presents the results, specifically the lessons learned and systematized according to a process analysis model.

Section 5 proposes a national-level organizational structure for preparing and conducting negotiations. Finally,

Section 6 discusses this study’s findings and their implications for future negotiations.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents a synthesis of the systematized lessons learned, thematically organized according to the PDCA + D cycle model described above.

Table 1 illustrates ITAIPU’s iterative negotiation process through the PDCA + D framework. The diagram highlights how each phase (Planning, Implementation, Monitoring, Adjustment) interacted with social dialogue mechanisms, emphasizing feedback loops that enabled progressive strategy refinement. Empirical examples mapped to each stage derive from interview data (

Supplementary Table S1) and treaty analysis (

Section 2.3).

4.1. Planning (Plan): Strategic Planning Objectives: Conditions for National Political Leadership and a Favorable Bilateral Environment

The relevant literature on natural resource governance highlights the central role of political leadership and institutional coordination in achieving strategic negotiation outcomes, particularly in asymmetric power contexts [

61,

62]. Moreover, strategic planning requires the ability to mobilize consensus around clear national objectives, especially in transboundary negotiations where state actors must reconcile domestic priorities with external constraints.

Interviewees highlighted the importance of leadership in defining objectives and guidelines in energy negotiations between Paraguay and Brazil. Stroessner’s personal leadership was mentioned as crucial in the initial negotiation round, while institutionalization became necessary after the 1989 coup d’état (on the night of 2 February and the early morning of 3 February 1989, a military coup was carried out (with citizen support, in conditions of exhaustion of the authoritarian regime of Alfredo Stroessner) that overthrew Stroessner’s government). Institutional coordination was identified as a key challenge in strengthening leadership, underscoring the importance of a unified vision. This finding resonates with the need for clear leadership and knowledge that is able to leverage circumstances [

61], as well as the creation of favorable bilateral conditions.

Several interviewees emphasized the role of authorities’ leadership in defining objectives and guidelines at both personal and institutional levels. Personal leadership was particularly relevant in the early Foz do Iguaçu and ITAIPU negotiations (1960s–1970s), with Stroessner, president for 35 years and leader of the majority party, personally involved in guiding negotiations. In the democratic period after the 1989 coup, personal leadership in guiding strategies was diluted. Nevertheless, interviewees commented that, in their opinion and in line with literature on Paraguayan policy-making style, institutionalism still needed to be developed to compensate for the loss of vertical authority. This statement relates to recent conclusions in the literature about the need for good natural resource management policies. The de facto disempowerment of leaders was identified in previous analyses examining the evolution of decision-making in Paraguay’s energy sector. Personal leadership must be replaced by national political leadership, enabling not only a platform for dialogue between political parties, but also the search for a minimum consensus on which to base strategic negotiation objectives aligned with national interests.

The need for institutional coordination was one of the most frequently expressed ideas. According to interviewees, the lack of coordination in Paraguay’s energy sector is a challenge that must be addressed to successfully reinforce personal and institutional leadership. This finding coincides with the previous literature and technical reports [

62,

63].

Another relevant aspect highlighted by the preparatory phase is the need to be informed to take advantage of circumstances. As Brown states, “knowing your stuff is essential to do your homework thoroughly. Part of this homework may be to anticipate as far as possible the positions of the people that you are going to negotiate with” [

61]. That is, knowledge creation and leadership are central and act as pivots.

In this context, several interviewees highlighted the receptiveness to national demands from their counterpart as being a facilitating element of negotiations: the atmosphere of bilateral relations. They mentioned that Stroessner’s acquaintances from his student days at a Brazilian military academy were relevant in establishing an atmosphere of trust conducive to consensus. Conditions of trust or a favorable negotiating environment on both sides of the table were again evident during the administrations of Nicanor Duarte Frutos and, particularly, Fernando Lugo in Paraguay. In fact, Lula da Silva, Brazil’s president for a period covering both Paraguayan presidents’ terms, concurred with the latter on political and economic paradigms, regional integration, and focus on social development, especially with Fernando Lugo, according to some interviewees from both Brazil and Paraguay.

Analysis of interviewee responses showed that not only is political leadership relevant, but also a favorable environment in inter-party relations is desirable, which could facilitate achieving strategic negotiation objectives. As evidenced in

Table 1, the Planning phase highlights how centralized leadership (Stroessner era) achieved short-term goals but proved unsustainable in democratic contexts, supporting the need for institutionalized coordination mechanisms. Thus, the findings suggest that, while personal leadership was effective in authoritarian contexts, democratic consolidation has exposed the need for robust, institutionalized coordination mechanisms. Political leadership today requires both technical preparation and the ability to build cross-sectoral consensus. Planning for future negotiations must, therefore, balance strong technical mandates with inclusive political strategies.

4.2. Doing (Do): Implementation and Analysis

The formulation of negotiation instructions or mandates has been identified in the literature as a key element, as negotiators are “instructed delegates” and not independent actors constrained only by the logic of expediency [

64]. Formulating negotiation mandates is, therefore, a critical element. Interviewees stressed the need for evidence-based mandates to know what they want to achieve by negotiating [

61].

A senior negotiator involved in ITAIPU’s early negotiation stages mentioned that, although negotiations were fraught with technicalities and overflowed with questions and information, there was a clear and concise mandate to “secure ownership of 50% of power generation associated with installed capacity”. “Stroessner gave me very precise instructions: there are three non-negotiable things: (i) 50% ownership of the generated energy, (ii) the possibility of creating jobs for Paraguayans, and (iii) the participation of Paraguayan companies in construction”. According to interviewees, having clear objectives and an internal mandate provided confidence in the implementation phase of negotiations.

After democratization, having precise guidelines also proved favorable in the implementation phase during Fernando Lugo’s administration, who came to power in 2008 with a plan focused on achieving energy sovereignty and increasing benefits for the country from binational entities.

Regarding the internal dynamics of negotiations, concerning technical aspects, interviewees considered one factor to be crucial: that technical discussions should not be contaminated by political criteria (keeping vested interests away from the negotiating table, at least regarding technical aspects). According to interviewees, one of the main problems arises from confusing both areas; misrepresentation of information at the technical-political level, public opinion, and oversimplification in political discourse risk contaminating political decision-making.

Both the clarity of the mandate brought to the negotiating table and the clarity of technical concepts are relevant, according to interviewees. Interviewees agreed that the negotiating team must be carefully selected in terms of multidisciplinary character, leadership capacity, and knowledge of negotiation strategies.

4.3. Checking (Check): Checking and Evaluating Strategies

Monitoring and feedback loops are key in negotiation cycles, allowing for real-time evaluation and adaptive strategy management [

61]. In this regard, most interviewees agreed that continuous monitoring during negotiations was important, but noted inconsistencies in practice. They recalled instances where inter-ministerial teams—particularly from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ANDE, and the Ministry of Public Works—played an advisory role in reviewing negotiation progress and suggested strategic adjustments.

However, the regularity and institutionalization of these practices were reported as inconsistent. Several respondents indicated that monitoring efforts often depended on the commitment of specific individuals rather than formalized procedures.

4.4. Acting (Act): Policy Decision-Making: Adjusting Strategies

Interviews revealed that strategic adjustments during energy negotiations have varied significantly depending on the level of political leadership and institutional commitment. While in some instances the active involvement of high-level authorities—particularly the President of the Republic and the Minister of Foreign Affairs—was perceived as instrumental in guiding negotiation strategies, several respondents pointed to cases where such leadership was limited or inconsistent. In these cases, the absence of visible political backing was associated with difficulty in redirecting processes and a lack of strategic adjustment. The composition of the negotiation team also emerged as essential. Participants emphasized that the effectiveness of negotiations often depended on whether representatives were appropriately matched with their counterparts—both in terms of seniority and expertise. Mismatches, such as assigning lower-level officials to engage with senior foreign counterparts, were viewed as detrimental to the country’s positioning. Conversely, examples of well-matched delegations were associated with more credible and assertive negotiation outcomes. The negotiating team must demonstrate consistency and strength in their actions, and a clear mandate is necessary to demonstrate leadership at the table. Knowledge gained from the verification phase is vital for maneuvering and meeting immediate decision demands. However, negotiations can be halted if necessary to better assess the situation. The lack of transparent domestic decision-making counterparts has been problematic on several occasions, underscoring the importance of robust and accountable decision-making.

Several respondents also discussed the role of follow-up and monitoring mechanisms. The absence of ongoing evaluation reduced the capacity to adapt strategies or incorporate lessons from prior stages. These findings suggest that the link between monitoring and decision-making remains underdeveloped and unevenly institutionalized and that, to ensure successful negotiations, follow-up monitoring must go beyond analysis and provide recommendations for adjusting strategies and even incorporate new systems if necessary. A detailed examination of negotiation progress should inform follow-up efforts.

4.5. Dialogue (+D): Bottom-Up Feedback and Consensus-Building

The interviewees recurrently identified an operational challenge: the disconnect between the negotiation process and its real-world implications, particularly concerning communication with the public and within the political arena, including non-governmental parties’ representation in Congress. Therefore, establishing a communication channel to engage public opinion and all political parties, especially those with parliamentary representation, is recommended.

Thus, public participation and consensus-building in the political arena have been identified as essential for the agreements to obtain the support of society and necessary parliamentary ratification. This dialogue and communication phase complements the classic PDCA cycle with the +D factor. The +D element introduces bottom-up feedback that is absent in initial stages of negotiation, but which gradually becomes more prominent in recent developments. Current evidence suggests that bidirectional population involvement tends to yield better outcomes.

On the one hand, it is recommended to design a communication strategy to make the information and the process transparent in order to make an active effort to deepen and enrich the top-down feedback from decision-makers to society.

On the other hand, the application of organized participatory mechanisms can facilitate the ownership of results, fostering consensus-building and acceptance. This approach also allows for contingency planning that creates the necessary flexibility for adaptation, even with an adversary.

Of the two processes, the first emphasizes manipulation and is a classic concern of diplomatic history and modern theories of interpersonal negotiation. The second emphasizes policy-making and bureaucracy, and is perhaps the most creative part of the act of bargaining. In future assessments of the role of negotiation in the modern international system, the internal process of redefining the boundaries of the international agreement appears likely to be more important than the external process of negotiating those boundaries. Thus, the way negotiators’ instructions are framed should be more critical to theorists than it appears to be now. This issue was specially addressed in focus groups.

Furthermore, the research suggests that the participation of political parties in discussions and follow-ups to the negotiation process should be emphasized. One potential approach would be to ensure that this participation should be carried out in the National Congress, since this body ratifies international agreements [

61,

65].

5. Proposal: A Framework for the Pre-Negotiation Stage Preparation

Building on the empirical findings from

Section 4 and the lessons systematized through the PDCA + D model, we propose a structured framework to guide the pre-negotiation stage of the current Annex C revision of the ITAIPU Treaty. This framework reflects the recurrent challenges and recommendations identified in interviews, treaty documents, and historical analyses, including gaps in strategic leadership, inconsistent coordination, insufficient monitoring, and limited stakeholder inclusion.

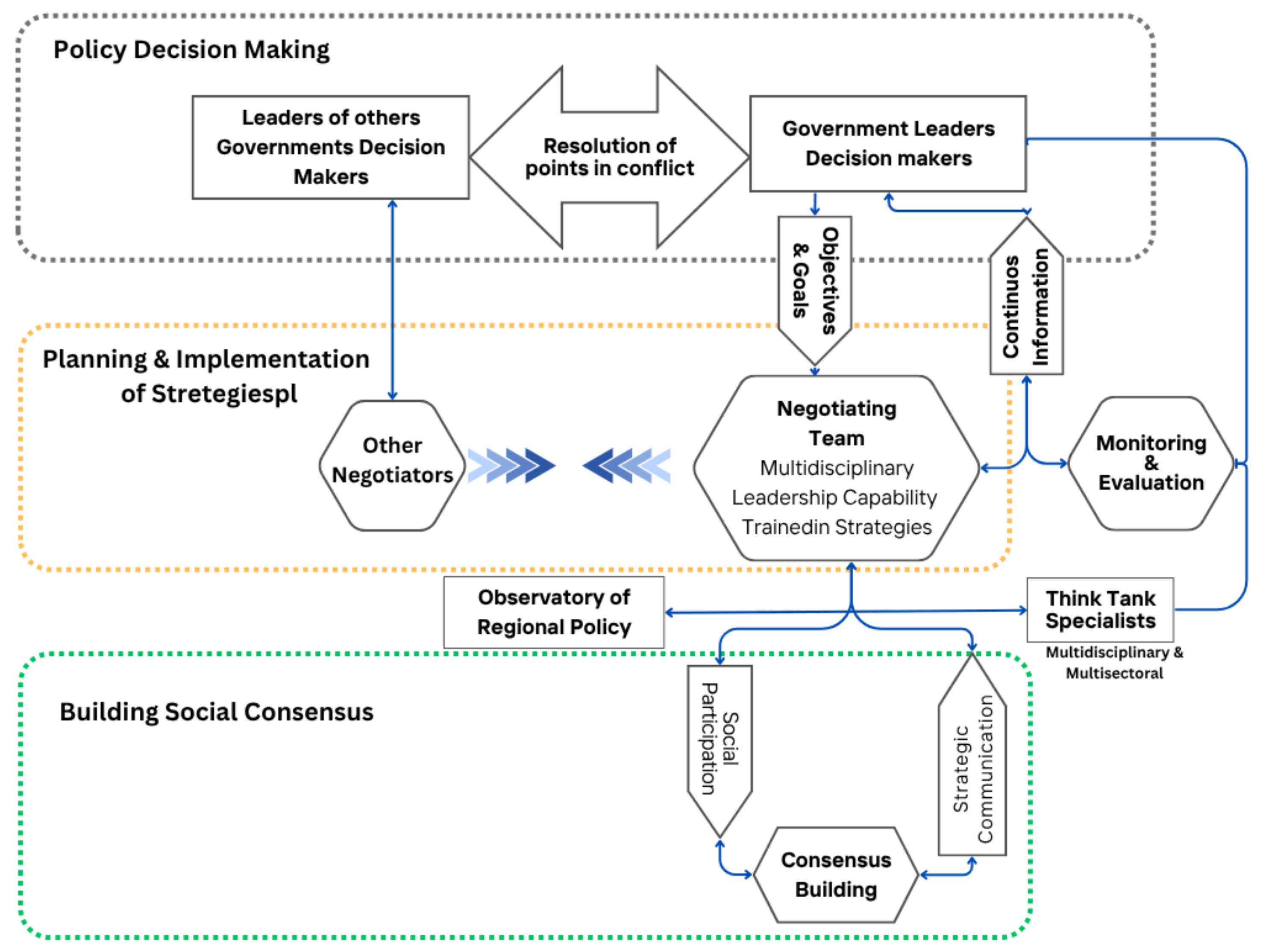

The proposed internal negotiation architecture, based on the table of lessons learned (

Supplementary Table S2), a proposal for the internal organization of the negotiation process was designed, depicted in

Figure 3, is structured around the adapted PDCA + D cycle, incorporating five interlinked dimensions: decision-making, implementation, monitoring and evaluation, participation and consensus-building, and a cross-cutting concern with environmental sustainability. This proposal complements the structure established under Executive Order 3173/2019 in Paraguay and aims to support continuous improvement, interest alignment, and greater public legitimacy. The proposed framework includes a formal participation element and a regional observatory to provide feedback on the decision-making and implementation levels. This additional structure aims to enhance the negotiation process’ effectiveness, ensuring that diverse stakeholders’ interests are represented and that environmental concerns are adequately addressed.

Moreover, as environmental concerns become increasingly urgent worldwide, negotiators must consider the environmental impacts of their decisions and collaborate to find equitable and environmentally respectful solutions. Zartman [

65] highlights the crucial role of attention to environmental issues in achieving a just and sustainable agreement.

5.1. Decision Level (Policy Strategy)—Informed by “Plan” and “Act”

As shown in

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.4, clear political leadership and a unified strategic vision were decisive in earlier negotiation successes, but have since become fragmented in Paraguay’s democratic period. To address this, the decision level must ensure that high-level authorities (heads of state, ministry of foreign affairs, etc.) define coherent national objectives and provide active, consistent support to negotiators. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the decision-making level marks the beginning of the negotiation cycle, where national objectives and interests are defined and strategies are developed accordingly. This level includes heads of state, ministers, foreign ministers, and ambassadors, who communicate the selected approach to the negotiation team working at the implementation level. The team develops tactics and courses of action to execute the chosen strategy. To ensure that the negotiation process aligns with national objectives and interests, actors at this level must have access to relevant feedback (

Section 5.4) and timely information on the progress of implementing negotiation strategies. This enables them to intervene and resolve critical and conflicting issues between the negotiating parties (

Section 5.3).

5.2. Implementation Level—Informed by “Do”

Section 4.2 highlights the critical role of clear mandates, multidisciplinary teams, and technical autonomy in effective negotiation execution. The implementation level of the framework operationalizes strategy through a core negotiation team equipped with technical, legal, economic, and geopolitical expertise.

The implementation level refers to the ongoing negotiation process itself. A multidisciplinary negotiation team with strong leadership skills and diverse expertise is essential, including designated negotiators and research centers. The team should develop tactics to give substance to the strategy with a concrete plan of action. Specialists should be involved in implementing proposals and evaluating prospects using a systemic analysis approach. In-depth knowledge of regional policy is necessary to track the evolution of the negotiation process at the “landscape” level [

66]. We propose the establishment of a regional policy watch to monitor plans and policies. This level is responsible for executing the strategy defined by decision-makers at the policy level while ensuring that the interests of various stakeholders are considered.

5.3. Monitoring and Evaluation Mechanism—Informed by “Check” and “Act”

As detailed in

Section 4.3 and

Section 4.4, the lack of formalized, consistent monitoring mechanisms has limited Paraguay’s ability to adapt negotiation strategies. The monitoring and evaluation mechanism proposed here institutionalizes real-time performance review and serves as a feedback loop between the decision-making and implementation levels. Interviewees described instances of ad hoc monitoring that relied on individual initiative rather than institutional design. To remedy this, a formal Management Unit and Communication Secretariat should oversee the evaluation process, consolidating progress updates, identifying inconsistencies, and informing both strategic adjustments and external communication.

The monitoring and evaluation mechanism is a crucial component of the negotiation process that facilitates two-way feedback between the decision-making level and the implementation level. This feedback loop helps update national interests (see

Section 5.4) and adjust strategy options and tactics accordingly, including social communication strategies. It serves as a communication channel within the two levels of governance to facilitate a continuous flow of information. The Management Unit and the Communication Secretariat can provide an appropriate framework for this feedback loop. A well-functioning feedback mechanism can ensure that different sectors of society perceive transparency in the negotiations and feel involved in the process. The Management Unit is especially important in consolidating a unified national agenda around strategic options and tactical courses of action. However, while some aspects of the negotiation process may need to be kept at the technical or political level, citizens demand greater transparency and information on the implications of these decisions.

5.4. Participation and Consensus-Building—Informed by “+D”

Section 4.5 underscored that social dialogue, public transparency, and political inclusivity are increasingly viewed as essential for negotiation legitimacy. The +D dimension in our framework is operationalized through structured stakeholder participation mechanisms, including political parties with legislative authority, civil society organizations, and especially historically marginalized groups such as indigenous communities.

These insights reflect a shift from the top-down model that dominated ITAIPU’s initial phases. Respondents emphasized the need for broader participation not only for democratic reasons, but also to secure ratification of international agreements and public ownership of negotiation outcomes. Participation is not only symbolic—it serves as a live monitoring tool and source of strategic feedback.

According to [

67], constructive participation forums and the participation of national stakeholders in preparing for the negotiation are crucial. Furthermore, stakeholder participation is also necessary for practical political considerations; a strong sense of ownership will lead to a solid motivation to ensure that the country’s negotiating position reflects its interests and serves as a live monitoring mechanism for negotiators [

67,

68]. Additionally, when the participation and consensus-building scheme includes political parties with parliamentary representation, it facilitates the ratification of international agreements, a necessary step for the entry into force of the negotiated agreement. This ratification is required in the countries participating in the negotiation process.

Historically marginalized segments of society should receive special attention, such as indigenous nations and communities, who have been poorly treated and whose ancestral traditions and ways of being have been disrespected in this context.

6. Conclusions

This study contributes to our understanding of international negotiations involving large shared natural resources by systematically capturing and analyzing first-hand experiences from key actors involved in the negotiations surrounding the ITAIPU hydropower project—one of the largest and most geopolitically significant bi-national infrastructure undertakings in the world. Through a combined methodological approach that draws on learning histories and the PDCA + D continuous improvement framework, the research offers an empirically grounded and theoretically informed model for structuring strategic negotiations over shared natural resources.

The findings of this work underscore the value of experiential knowledge in identifying best practices and key factors that have shaped past negotiation processes, identifying recurrent challenges. These insights were categorized along the phases of Planning, Implementation, Monitoring, Adjustment, and Dialogue, providing a structured synthesis of lessons learned. We pose that this work not only contributes to the literature on large-scale transboundary resource governance, but also offers actionable guidance for the design of future negotiation processes.

The main finding of this research: The proposed pre-negotiation framework is grounded in these lessons and is tailored to the ongoing revision of Annex C of the ITAIPU Treaty. It emphasizes inter-institutional coordination, technical autonomy, stakeholder participation, real-time feedback mechanisms, and environmental sustainability as essential components of a robust negotiation architecture. While developed in the context of Paraguay and Brazil, the model is adaptable to other regional electricity integration efforts and to negotiations over shared infrastructures in similarly complex governance settings.

Building mutual trust and including diverse actors in the negotiation process are widely used as key elements for successful outcomes, as evidenced by various international experiences. In the case of ITAIPU, one of the most relevant lessons highlighted by [

12] is the co-ownership of the infrastructure, which constitutes a unique institutional arrangement. Our study also emphasizes the importance of establishing a clear co-governance structure and, above all, defining precise negotiation objectives, as expressed through directives from the highest national authorities. In addition, this work contributes empirical evidence that supports the design of internal organizational frameworks to guide countries in the preparation and development of negotiation processes.

In the face of increasing negotiation prospects, as the Paraná River’s hydropower potential continues to be explored and initial agreements require revision, the main objective of this work was to provide a framework for the pre-negotiation stage that can be implemented at the national level. It is emphasized that this framework and the lessons learned can be used to advance regional electricity integration efforts in South America and potentially in other contexts with similar challenges.

Historical and geopolitical analyses allowed for the identification and contextualization of crucial elements. The application of the learning histories methodology facilitated the recording and analysis of personal accounts, while the Deming cycle analysis provided a structure for classifying and presenting the lessons learned. This combined approach enabled the elaboration of an organizational proposal for negotiation based on these lessons. In this context, we consider that the main contribution of this work is the systematization of lessons learned about international negotiations, merging learning histories with the continuous improvement approach of the Deming cycle, thus offering a replicable and adaptable model for managing strategic negotiations over shared resources. While acknowledging this study’s inherent limitations, the findings open avenues for future comparative and quantitative research that can further refine and validate the proposed framework.

This study presents several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. While the research incorporated perspectives from Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina, the interview sample disproportionately represented Paraguayan stakeholders (62%), potentially overemphasizing Paraguay’s negotiation position. Although the data were triangulated with treaty documents and regional media reports, this imbalance may affect the comprehensive understanding of power dynamics. The temporal scope concluded in 2023 excludes recent developments in Annex C revisions, a deliberate choice to maintain focus on historical process-tracing, but which limits analysis of contemporary negotiations.

Theoretical constraints also merit discussion. The adapted PDCA + D framework, while valuable for structuring lessons, may oversimplify complex, non-linear negotiation processes observed in the ITAIPU case—particularly the overlapping “Act” and “Check” phases during the 2009 Lula-Lugo negotiations.

These limitations suggest three productive avenues for future research: (a) comparative validation of the PDCA + D model in other transboundary disputes (e.g., Nile Basin [

12]) to assess its transferability; (b) quantitative supplementation through econometric analysis of energy revenue distributions, building on existing macroeconomic models; and (c) participatory action research to examine post-agreement implementation gaps, particularly regarding compensation to indigenous communities affected by ITAIPU’s construction. Such studies would address current methodological constraints while also advancing the framework’s practical utility for complex resource negotiations.