Data-Based Analysis on the Economic Value of Fishery Observer Programs in International Fisheries Management: Insights from Korea’s Distant Water Fisheries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Survey Design

2.2. Analytical Procedure

3. Results

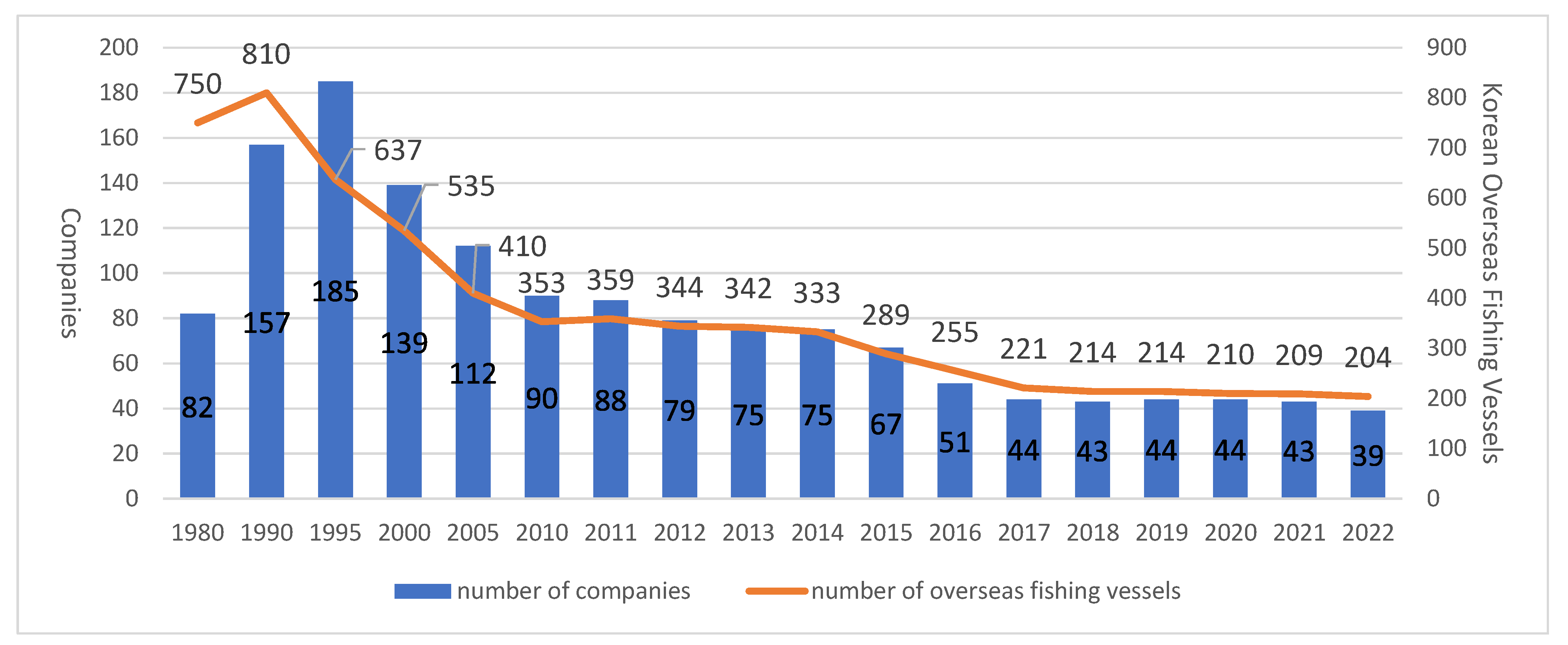

3.1. Descriptive Information

3.2. Estimation Results

3.3. Reason for Supporting the International Fishery Observer Program

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Liddick, D. The dimensions of a transnational crime problem: The case of IUU fishing. Trends Organ. Crime 2014, 17, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvestad, C.; Kvalvik, I. Implementing the EU-IUU regulation: Enhancing flag state performance through trade measures. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 2015, 46, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallic, B.L.; Cox, A. An economic analysis of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing: Key drivers and possible solutions. Mar. Policy 2006, 30, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.-M. International actions against IUU fishing and the adoption of national plans of action. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 2015, 46, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Asche, F. Can US import regulations reduce IUU fishing and improve production practices in aquaculture? Ecol. Econ. 2021, 187, 107084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, A.J.; Skerritt, D.J.; Howarth, P.E.C.; Pearce, J.; Mangi, S.C. Illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing impacts: A systematic review of evidence and proposed future agenda. Mar. Policy 2022, 139, 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamahefazafy, M.; Touron-Gardic, G.; March, A.; Hosch, G.; Palomares, M.; Failler, P. Sustainable development goal 14: To what degree have we achieved the 2020 targets for our oceans? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 227, 106273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Garcia, S.; Barclay, K.; Nicholls, R. Can anti-illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing trade measures spread internationally? Case study of Australia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 202, 105494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vince, J.; Hardesty, B.D.; Wilcox, C. Progress and challenges in eliminating illegal fishing. Fish Fish. 2021, 22, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Legorburu, G.; Fedoruk, A.; Heberer, C.; Zimring, M.; Barkai, A. Increasing the functionalities and accuracy of fisheries electronic monitoring systems. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 901–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Fisheries Resources Agency. Enhancement Strategies for Systematic Management of International Observers; Korea Fisheries Resources Agency: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.I.; Kim, Z.G. Study on the status and improvement of national observer programs for Korean distant water fisheries. J. Korean Soc. Fish. Ocean Technol. 2024, 60, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Z.G.; Kwon, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, D.N.; Lee, J. A study on improving the IUU Fishing Index of Korea’s distant water fisheries. J. Korean Soc. Fish. Ocean Technol. 2023, 59, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. Inducing state compliance with international fisheries law: Lessons from two case studies concerning the Republic of Korea’s IUU fishing. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2019, 19, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, M.M.; Cubas, A.L.V.; Silvy, G.; Magogada, F.; Moecke, E.H.S. Impacts of illegal fishing in the inland waters of the State of Santa Catarina–Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 180, 113746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, N.; Mourato, S.; Wright, R.E. Choice Modelling Approaches: A Superior Alternative for Environmental Valuatioin? J. Econ. Surv. 2001, 15, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Boyle, K.J.; Adamowicz, W.; Bennett, J.; Brouwer, R.; Cameron, T.A.; Hanemann, W.M.; Hanley, N.; Ryan, M.; Scarpa, R.; et al. Contemporary Guidance for Stated Preference Studies. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 4, 319–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, M.; Loomis, J.; Kanninen, B. Statistical efficiency of double-bounded dichotomous choice contingent valuation. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1991, 73, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software, Release 18; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Feldman, A. Introduction to Contingent Valuation Using Stata (MPRA Paper No. 41018); Centro de Investigacion y Docencia Economicas (CIDE): Toluca, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deaton, A.; Muellbauer, J. Economics and Consumer Behavior; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mankiw, N.G. Principles of Economics; Harcourt College Publishers: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Korea. Future Household Estimates; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.-K.; Ryu, J.-G.; Sim, S.-H.; Oh, T.-G.; Lim, B.-G. Economic Valuation of the Off-Shore Fisheries Stock Enhancement Project. J. Fish. Bus. Adm. 2021, 52, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-M.; So, A.-R.; Shin, S.-S. A Study on the Non-market Economic Value of Marine ranches and Marine Forests Using Contingent Valuation Method. J. Fish. Bus. Adm. 2020, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-R.; Kim, J.-H.; Yoo, S.-H. Public perspective on constructing sea forests as a public good: A contingent valuation experiment in South Korea. Mar. Policy 2020, 120, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskaite, L.; Cook, D.; Davíðsdóttir, B.; Ögmundardóttir, H.; Roman, J. Willingness to pay for expansion of the whale sanctuary in Faxaflói Bay, Iceland: A contingent valuation study. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 183, 105026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.D. Estimating Residents’ Willingness to Pay for Wetland Conservation Using Contingent Valuation: The Case of Van Long Ramsar Protected Area, Vietnam. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2021, 22, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell, S.; Wilhelmsson, M. Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Housing. J. Hous. Res. 2011, 20, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Defining the target for valuation using CVM analysis | The first stage of the study is to define the target for value estimation. This study focuses on estimating the socio-economic value generated by the Korean fishery observer program. |

| 2 | Identifying and communicating the economic and social value provided by the Korean fishery observer program | The second stage involves identifying the social and economic value provided by the fishery observer program in distant water fisheries and creating explanatory materials to convey this information to survey respondents. In this study, video explanatory materials were developed to effectively communicate these values and improve respondents’ understanding. |

| 3 | Determining the payment vehicle and developing survey questions to measure maximum willingness to pay | The third stage is to determine the payment vehicle that will be used to measure the maximum willingness to pay and to develop survey questions accordingly. This study identified additional household income tax as the payment vehicle, and the initial bid range was determined based on previous research. |

| 4 | Validating the survey through a pilot survey | The final stage involves conducting a pilot survey to validate the effectiveness of the survey. |

| Transcripts |

|---|

| Do you know about IUU fishing, which hinders sustainable fisheries? IUU stands for illegal, unreported, and unregulated. If a country is designated as an IUU fishing country by the international community, it may be banned from exporting marine products and restricted from entering major foreign ports on its vessels. It will also be subject to international condemnation. Efforts are being made to eradicate IUU fishing and to strengthen the transparency and traceability of fisheries, and a representative example is the international fishery observer programs. The Republic of Korea is implementing international fishery observer programs that send observers aboard the national flagged vessels of deep-sea fishing vessels operating in various waters, including the Pacific, Atlantic, and Antarctic oceans, to collect data on fishing statistics, conduct fact-finding surveys, conduct biological surveys, and investigate whether regulatory and conservation measures are being implemented. Observers with public interest purposes board fishing vessels to induce legal fishing and perform various roles, such as collecting scientific data through research activities. One of the main roles of the observer is to report on fishing activities. Recently, consumers worldwide have shown a growing interest in ethical consumption. In the case of marine products, the fishing process is carefully evaluated, including protecting marine ecosystems and fish species and compliance with international regulations, and sustainable marine products are certified to encourage valuable consumption. Consumers pay extra for products with the trust of the certification system, and companies invest the additional profits in sustainable fisheries, creating a virtuous cycle in the industry. The basis for such certification requires presenting evidence through an observer program. However, financial resources for program operation are necessary to prevent illegal fishing, ensure marine ecosystem diversity, and ensure sustainable fishing grounds through the smooth operation of the observer program. How much would you be willing to pay if you participated as a citizen in securing the financial resources necessary to maintain sustainable distant water fisheries through fishery observer programs? To raise these funds, we need to increase the total income tax paid by your household by an additional amount each year for the next five years. Would your household be willing to pay an additional [randomly selected initial amount] KRW annually in total household income tax for the next five years to support the operation of the international observer program? (1) Yes (2) No |

| Variables * | Definitions | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Gender of the survey participants (male = 1, female = 0) | 0.510 | 0.50 |

| Age | Age | 42.910 | 12.45 |

| Marital Status | Marital status (married = 1, single = 0) | 0.597 | 0.49 |

| Family Size | The number of family members | 2.961 | 1.19 |

| Household Income | Gross monthly household income (KRW) | 5,072,500 | 2,414,917 |

| Initial Bid Amount (KRW) | First Answer: Yes | First Answer: No | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Answer | Second Answer | |||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||||

| 1000 (USD 0.77) | 87 | 62 | 6.2% | 25 | 2.5% | 38 | 5 | 0.5% | 33 | 3.3% |

| 3000 (USD 2.31) | 77 | 50 | 5.0% | 27 | 2.7% | 48 | 9 | 0.9% | 39 | 3.9% |

| 5000 (USD 3.85) | 64 | 36 | 3.6% | 28 | 2.8% | 61 | 12 | 1.2% | 49 | 4.9% |

| 7000 (USD 5.38) | 62 | 36 | 3.6% | 26 | 2.6% | 63 | 16 | 1.6% | 47 | 4.7% |

| 9000 (USD 6.92) | 57 | 27 | 2.7% | 30 | 3.0% | 68 | 15 | 1.5% | 53 | 5.3% |

| 12,000 (USD 9.23) | 55 | 27 | 2.7% | 28 | 2.8% | 70 | 19 | 1.9% | 51 | 5.1% |

| 15,000 (USD 11.54) | 57 | 22 | 2.2% | 35 | 3.5% | 68 | 17 | 1.7% | 51 | 5.1% |

| 20,000 (USD 15.38) | 55 | 17 | 1.7% | 38 | 3.8% | 70 | 16 | 1.6% | 54 | 5.4% |

| Total | 514 | 277 | 27.7% | 237 | 23.7% | 486 | 109 | 10.9% | 377 | 37.7% |

| Variables | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p-Value | 95% Conf. Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household income | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 1.28 | 0.201 | −0.0002 | 0.0009 |

| Age | 173.6496 | 65.9344 | 2.63 | 0.008 | 44.4205 | 302.8786 |

| Gender | 441.9979 | 1697.1420 | 0.26 | 0.795 | −2884.3390 | 3768.3350 |

| Household size | −1231.6850 | 566.9954 | −2.17 | 0.030 | −2342.9750 | −120.3941 |

| Online purchasing | 949.5505 | 391.3225 | 2.43 | 0.015 | 182.5724 | 1716.5290 |

| Online seafood info | 1243.2790 | 405.8338 | 3.06 | 0.002 | 447.8597 | 2038.6990 |

| Freq. of seafood consumption | 460.8786 | 166.6569 | 2.77 | 0.006 | 134.2371 | 787.5202 |

| Constant | −6115.4920 | 5845.3940 | −1.05 | 0.295 | −17,572.2500 | 5341.2700 |

| Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p-Value | 95% Conf. Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual willingness to pay to support the international fishery observer program | USD 9.45 | 3.01 | 3.14 | 0.002 | 3.55 | 15.36 |

| Item | |

|---|---|

| Weighted annual household WTP | USD 7.01 |

| Annual public benefits | USD 153,097,825 |

| Reasons | Freq. | % |

| 1. To prevent illegal fishing | 232 | 31.3% |

| 2. To enhance national prestige | 24 | 3.2% |

| 3. To contribute to scientific data collection on marine resources | 18 | 2.4% |

| 4. To consume eco-friendly seafood | 118 | 15.9% |

| 5. To preserve and protect marine ecosystems | 166 | 22.4% |

| 6. To protect endangered species (whales, sharks, turtles, seabirds, etc.) | 49 | 6.6% |

| 7. To prevent pollution of the marine environment | 60 | 8.1% |

| 8. To facilitate the Korean fishery industry’s access to overseas fishing grounds | 10 | 1.4% |

| 9. To ensure the acquisition of distant water seafood products | 7 | 0.9% |

| 10. For sustainable fisheries | 49 | 6.6% |

| 11. To protect fisheries resources on the high seas | 8 | 1.1% |

| 12. Other | 1 | 0.1% |

| Total | 742 | 100% |

| Reasons | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I can’t afford to pay extra. | 65 | 25.2% |

| 2. Fishery observer programs are not relevant to me. | 23 | 8.9% |

| 3. Distant water fisheries are not of value to me. | 2 | 0.8% |

| 4. I am not interested in sustainable fishing. | 10 | 3.9% |

| 5. I don’t trust the effectiveness of fishery observer programs. | 28 | 10.9% |

| 6. I don’t think fishery observer programs will work well. | 15 | 5.8% |

| 7. Fishery observer programs are unnecessary for sustainable fisheries. | 5 | 1.9% |

| 8. I pay enough taxes already. | 91 | 35.3% |

| 9. The additional taxes will not be used for the stated purpose. | 18 | 7.0% |

| 10. Alternative means of monitoring other than fishery observer programs are needed. | 1 | 0.4% |

| Total | 258 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.-G.; Go, D.-H.; Yi, S. Data-Based Analysis on the Economic Value of Fishery Observer Programs in International Fisheries Management: Insights from Korea’s Distant Water Fisheries. Water 2025, 17, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010133

Kim Y-G, Go D-H, Yi S. Data-Based Analysis on the Economic Value of Fishery Observer Programs in International Fisheries Management: Insights from Korea’s Distant Water Fisheries. Water. 2025; 17(1):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010133

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yeon-Gyeong, Dong-Hun Go, and Sangchoul Yi. 2025. "Data-Based Analysis on the Economic Value of Fishery Observer Programs in International Fisheries Management: Insights from Korea’s Distant Water Fisheries" Water 17, no. 1: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010133

APA StyleKim, Y.-G., Go, D.-H., & Yi, S. (2025). Data-Based Analysis on the Economic Value of Fishery Observer Programs in International Fisheries Management: Insights from Korea’s Distant Water Fisheries. Water, 17(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010133