Abstract

Transboundary waters account for a significant portion of global freshwater resources, yet their management is often challenging. The Nile River basin faces significant challenges owing to the complex history and unique context of the basin. Examining the experience of other transboundary basins can offer insights for the effective management of the Nile waters. This paper aims to extract contextual lessons for the Nile from global transboundary water management practices. To that end, we performed a scoping literature search to identify well-researched transboundary water management practices from across the world, selected key case studies, and analyzed their management practices. We discussed the context of the Nile and organized the unique challenges of the basin in five themes, and we discussed how global experiences could provide valuable insights for the Nile basin within each theme. Trust building, the need for equitable water use frameworks, a strong river basin organization, the nuanced role of external actors, and the impact of broader political context were major themes that emerged from the analysis of the Nile context. Within each theme, we presented experiences from multiple basins to inform transboundary water management in the Nile basin.

1. Introduction

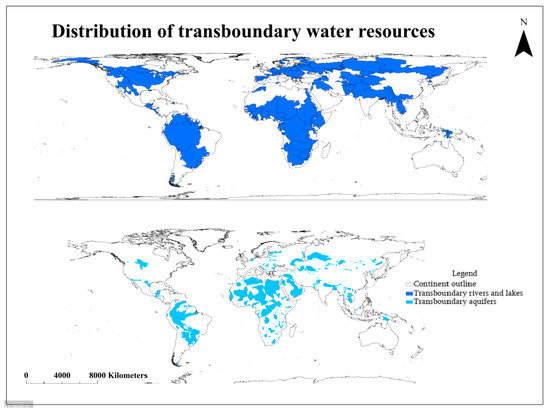

The United Nations defines transboundary waters as “any surface or ground waters that mark, cross, or are located on the boundaries between two or more states” [1]. There are 313 transboundary rivers and lakes and 592 transboundary aquifers (See Figure 1) shared by 153 countries [2,3,4]. These shared resources account for 60% of the global readily available freshwater resources serving 42% of the global population [4,5]. The proper management and utilization of these resources is thus integral to achieving the global water security agenda (SDG 6) [6].

Figure 1.

Distribution of transboundary water resources across the world. Data source: [2,3].

The use and management of transboundary waters are complex for several reasons. Countries often have competing and, at times, conflicting interests in shared resources [7,8]. Countries’ claims of a shared resource also tend to be larger than their endowments (a notable example being the Nile Basin) [9]. Moreover, the intersection of hydrological and political boundaries in transboundary waters can stretch the system beyond the hydrological limits, adding more actors and factors to negotiations (note the case of the Jordan basin). Regional and global actors with various economic and geopolitical interests and power dynamics influence transboundary water use discussions [10]. Transboundary water management decisions thus entail serious political considerations in addition to hydrological ones. In addition, each transboundary basin faces challenges unique to its context. Factors such as the basin’s size, geographic configuration, number of riparian countries, water availability, dominant uses and users, major water concerns, demographics, history, social, economic, and political dynamics, power asymmetries, and the basin’s place in broader regional and global dealings all influence transboundary water governance. For instance, the governance of the Nile River is heavily impacted by history and power asymmetries between upstream and downstream countries, while the Mekong River basin illustrates the significant role of economic dynamics and dominant water uses. The Jordan basin illustrates the significant role of broader regional actors, while the Danube River basin highlights the importance of historical and political dynamics in shaping water management strategies. More examples and further discussion of how these factors impact decision-making processes in different basins are given in detail later in this paper.

The Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (the UN Convention), the highest law on transboundary water management, offers “basic standards and rules for cooperation…that may be applied and adjusted to suit the characteristics of particular international watercourses”) [11,12,13]. It establishes the principles of equitable use and no significant harm as guiding tenants. However, the dichotomous relationship of these two principles is widely debated [11,12,14,15,16,17]. Upstream countries typically prefer the principle of equitable use, believing it favors their interests, while downstream countries lean towards the principle of no significant harm, as they see it as more beneficial to their own concerns. For example, in the Nile River Basin, upstream countries argue that equitable use permits them to utilize the water resources for their development needs. However, downstream countries argue these actions are causing significant harm [11,18]. Conversely, efforts to ensure no significant harm to downstream countries are perceived by upstream nations as preventing their equitable use of the river [11,18]. The convention provides factors to consider in determining equitable use (listed in Article 6), but it does not clarify what constitutes significant harm (note Article 7). In the Mekong and Nile River Basins, for instance, this lack of clarity has caused disagreements over dam construction and water utilization. Thus, reconciling these principles and determining what constitutes equitable use and significant harm in the context of individual basins becomes a case-by-case exercise [19,20]. In addition to the selective preference and interpretation of the principles, many countries have also raised reservations over the obligation of prior notification on planned measures (Article 12) as well as the dispute resolution mechanisms (Article 33) of the convention [11,18]. Due to these factors, despite coming into force in 2014, the convention has still not been ratified by many notable countries, including all the Nile basin countries, India, Pakistan, China, Turkey, the US, Canada, Brazil, and Russia. These nations represent major regions and watercourses around the world, underscoring the complex difficulties in achieving widespread agreement and cooperation on transboundary water management.

Strong basin-wide institutional structures play a crucial role in facilitating effective transboundary water management. These structures can take various forms, with river basin organizations (RBOs) being the most common [21]. The International River Basin Organization Database [22] identifies more than 120 RBOs. RBOs are designed to foster cooperation among riparian states by providing platforms for negotiating water allocations, sharing hydrological data, coordinating basin-wide management efforts, and resolving disputes [23,24]. RBOs widely differ in their institutional structure, legal mandate, size, organization, membership, inclusiveness, and financing and have achieved varying levels of success across basins [23,24]. Successful RBOs, such as those in the Senegal, Mekong, Colorado, and Danube River basins, demonstrate that strong institutional frameworks can promote sustainable water use, mitigate conflicts, and address challenges posed by climate change and increasing water demands. Despite this, over two-thirds of transboundary river basins lack a cooperative water use framework [25]. According to the UN, as of 2021, only 24 countries out of the 153 countries which share transboundary resources have reported having an operational arrangement for cooperation over shared resources [4]. The World Bank notes more than 2/3 of transboundary rivers lack any type of cooperative framework [26] This gap underscores the urgent need for more robust cooperative arrangements to manage shared water resources sustainably.

Insights from experiences from other basins can help navigate some of the complexities around transboundary water management. Given the prevalence of transboundary waters, there is a vast body of research on global transboundary water management practices. A quick search of the topic on the Web of Science (Clarivate) database in 2024 resulted in more than 15,000 citations (https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/summary/8f343009-8716-4291-9393-b98a0ecad578-d9c11a90/relevance/1, accessed on 4 June 2024) on the lessons, experiences, and best practices of transboundary surface water allocation, utilization, management, and governance. These records offer valuable general insights into factors contributing to both successful and unsuccessful transboundary water management and can inform interventions in various basins [27,28,29,30]. However, the contextualization of best practices to individual basins remains underdeveloped in the literature, limiting their applicability across diverse hydrological and geopolitical contexts.

The Nile River basin is a complex transboundary river basin with unique characteristics complicating its transboundary water management. According to the FAO and UN, the Nile River basin is already critically water-stressed as the total freshwater withdrawal exceeds the total freshwater resources [31]. Historical imbalances in water use and the lack of an equitable and sustainable water use framework have made Nile water use contentious. The combined pressures of a growing population, the consequent rise in water demand, and the stress of climate change have heightened the urgency for the equitable and sustainable utilization of this shared resource. Drawing contextual lessons from global transboundary water practices tailored to the specific needs of the Nile could provide valuable insights for improving transboundary water governance in the region.

In this paper, we aimed to assess global practices in transboundary water management to draw contextual lessons for the Nile River basin. We conducted a scoping literature review to identify exemplary transboundary water management practices from five continents followed by an in-depth examination of selected basins. We organized the contextual challenges of the Nile basin into five themes and discussed how global experiences could provide insights for the Nile basin within each theme.

2. Study Site: The Nile River Basin

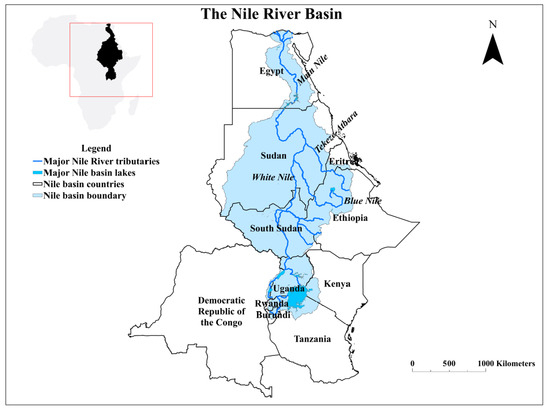

The Nile River basin is a transboundary river basin located in the northeastern part of Africa (See Figure 2). The Nile River is most notable for being the longest river in the world at 6695 km. It drains approximately 10% of the African land mass, covering almost 3.2 million square kilometers, crossing 11 countries with diverse climatic, geomorphological, hydrologic, demographic, and socioeconomic profiles [32]. The Nile River has two main tributaries, the Blue Nile and the White Nile, originating from the highlands of Ethiopia and the equatorial lakes region, respectively. More than 86% of the Nile water originates from Ethiopia, while the rest is accounted for by equatorial basin countries [32,33]. Despite its length, the Nile is not a very large river. Historically, the annual discharge of the river has been estimated to be about 84 billion cubic meters (BCM), although recent studies suggest a higher discharge (90–97 BCM) [32,34]. This discharge is very small compared to rivers of similar length like the Amazon (>5600 BCM at 6400 km) or the Yangtze River (960 BCM at 6300 km) [35]. Around 320 million people living within the basin and more than 500 million in the 11 riparian countries already depend on the Nile River for their basic needs, many of whom are dealing with high levels of poverty, food, water, and energy insecurity [32]. This population is expected to double by 2050, exponentially increasing water demand and exacerbating existing water stress.

Figure 2.

The Nile River basin: location, extent, countries, and tributaries.

2.1. Historical Water Use

Since ancient times, the Nile has been instrumental in the economy, politics, religion, identity, and nation-making efforts in the region [36,37,38]. It holds significant importance in the historical, psychological, and cultural makeup of the people of the basin [38,39]. The control, utilization, and governance of the Nile has always been a crucial concern to riparian countries and external actors involved in the basin. Thus, beyond a hydrological endeavor, the management of the Nile has implications for how people and countries relate to each other and, by extension, the broader peace and stability of the region.

Historical water management in the Nile basin was centered around efforts to guarantee the uninterrupted flow of water to downstream Egypt. This objective was pursued by various ruling powers, including the Romans (30 BC–641 AD) and the Ottomans (1517–1798) who sought to unify the basin under one rule. Colonial-era powers, such as the British, French, Italians, and Belgians, further solidified this focus through multiple water use arrangements. Key agreements from this era include those made in 1891, 1902, 1906, 1925, 1929, 1934, and 1949, culminating in the 1959 agreement, which continues to influence current water use discussions in the basin (See Table 1) [40,41,42].

Table 1.

Summary of historical water use treaties on the Nile.

These agreements were bilateral or trilateral, signed primarily between the colonial powers of the time, to guarantee the uninterrupted flow of water downstream mainly to protect colonial agricultural interests in the basin [40]. Early colonial-era agreements had stipulations preventing the significant use of water upstream ensuring the maintenance of downstream flow. The 1929 agreement between the UK and Egypt went further by volumetrically allocating Nile water, assigning 48 BCM to Egypt and 4 BCM to Sudan to support British agricultural expansion while granting Egypt “veto power” over upstream infrastructure projects [43]. Building upon this agreement, the 1959 agreement, aimed at the full utilization of the Nile River, allocated the entire flow of the Nile at the time (84 BCM) between Egypt (55.5 BCM), Sudan (18.5 BCM), and evaporation loss (10 BCM) [44]. This agreement did not allocate water for upstream water source countries. Instead, it stipulated if the other riparians claim a share of the Nile, Egypt and Sudan will “…jointly consider and reach one unified view regarding the said claims” and that if these claims were deemed acceptable, “the accepted amount shall be deducted from the shares of the two Republics in equal parts, as calculated at Aswan” [44]. Such historic instances which prioritized colonial interests and downstream water use at the expense of upstream water use have entrenched inequitable water use paradigms and deep-seated mistrust among basin countries [38]. These sentiments coupled with growing water demand have made the question of equitable use of the Nile a priority agenda in the basin, especially in recent years.

2.2. Current Water Use

Historical agreements have profound and enduring impacts on current water use dynamics in the Nile basin. For instance, the 1959 agreement, which allocated the entirety of Nile water to Egypt and Sudan, severely limits the development options for upstream nations striving to harness Nile resources for economic and social progress. This imbalance remains a significant point of tension, evident in disputes such as those surrounding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Terms like “historical rights” and “acquired shares”, referring to water rights/shares of downstream countries as stipulated in historical agreements, as well as veto power over basin development projects introduced by these agreements, prioritize downstream countries’ rights and undermine the sovereignty of upstream nations, fostering distrust and complicating cooperation efforts. Despite criticisms, downstream countries rely on these agreements to justify their dominant water use rights and insist on their preservation. Upstream countries, on the other hand, reject them as relics of colonial imposition, unjust distribution, and an affront to their sovereignty [45]. Nevertheless, the allocation numbers and concepts from these agreements persist in basin-wide scientific studies, political negotiations, and social discourse [35]. The enduring presence of these agreements, which disregard the water rights of all riparian countries, fundamentally questions the equitable rights of all riparian countries to the Nile waters—a critical prerequisite for meaningful regional water management discussions. The impact of these historical agreements also hinders current water use discussions, notably seen in the negotiation of the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA). Initiated in 1997, the CFA aimed to establish a new governance framework for the Nile basin. However, Article 14b became a contentious issue between upstream and downstream countries. The version of Article 14b agreed upon by all upper riparian countries read “Nile Basin States therefore agree, in a spirit of cooperation not to significantly affect the water security of any other Nile Basin State”, while the proposal by Egypt and Sudan read “…not to adversely affect the water security and current uses and rights of any other Nile Basin State” (emphasis added) [46]. The emphasis on water security by upstream countries versus the focus on safeguarding their current uses and rights established under the 1959 agreement by downstream countries underlies the impasse over the CFA. All Nile basin countries agreed to annex Article 14b, and after 13 years of negotiation, the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) was opened for signature in 2010. Article 14b was slated to be resolved by the Nile River Basin Commission within 6 months of its establishment following ratification by at least six countries. However, there has been no progress in resolving the impasse to date. The CFA has been signed by six upstream riparian countries and ratified by four, but Egypt and Sudan have not yet signed the agreement. This disagreement highlights how historical agreements continue to shape and constrain current negotiations over the governance of the Nile Basin.

3. Methods

We conducted a comprehensive scoping literature review to identify and analyze well-researched case studies on transboundary water management practices. The search was performed using the Web of Science Core Collection on the topic of publications, i.e., title, abstract, and author keywords of publications. Our query aimed to capture the literature on surface transboundary waters, emphasizing case studies that illustrated management approaches, governance experiences, lessons, and best practices.

The initial query used keywords “Transboundary water OR transboundary river AND Manage* OR govern* OR alloc* OR util* AND lessons OR experiences OR (best practices) OR (good practices) NOT aquifer* OR (groundwater) AND case OR (case stud*)”. This query yielded 95 citations, including 83 peer-reviewed articles, 7 proceeding papers, 6 book chapters, 5 review articles, and 1 book review. The search was not limited by time, but all publications returned were published between 1997 and 2024.

Excluding the book review, we screened the 94 publications for relevance by reviewing the abstracts and, when necessary, the full texts. Criteria for inclusion prioritized papers that provided insights into management and governance approaches, lessons, and best practices of case studies in transboundary water management. This screening resulted in 60 papers, out of which 12 featured river basins in Africa, 17 in Asia, 7 in North America, 15 in Europe, 3 in the Middle East, and 1 in South America. There were 2 case studies focused on Australia as well, one of which featured multiple best practices from across the world. The case studies featured frequently in the literature were identified for further study using the snowball approach. The Nile, the Senegal, the Orange-Senqu River basins from Africa, the Mekong, the Brahmaputra–Ganges–Meghna and the Indus River basins from Asia, the Colorado River basin from North America, the Jordan in the Middle East, and the Danube and the Rhine from Europe dominated the literature, being featured more than 35 times in our final subset of the literature, and were thus chosen for further analysis.

We contrasted these case studies with the UN’s best transboundary water practices database [47] and found out that most of the case studies were featured on the database. This overlap reinforces the rationale for the selection of these case studies that represent global best practices in transboundary water management. In the subsequent section, we synthesized findings from these case studies, organized the contextual challenges of the Nile basin into five themes, and discussed how global experiences could provide insights for the Nile basin within each theme.

4. Exemplary Practices in Transboundary Water Management

4.1. The Rio Grande and Colorado River Basins: North America

The Rio Grande River basin, shared by the US and Mexico, illustrates the importance of addressing historical inequities, the limitations of fixed water allocations, and the necessity for flexible and evolving treaties. In 1894, Mexico claimed that increased irrigation by the US from the Rio Grande had caused a decline in river levels in Mexico [48]. Initially, the US attributed the decline to drought rather than increased usage but eventually entered negotiations with Mexico. In consulting the US government, Attorney General Judson Harmon invoked the principle of absolute territorial sovereignty (thereafter also called the Harmon Doctrine), stating “the United States is under no obligation to Mexico to restrain its use of the Rio Grande because its absolute sovereignty within its own territory entitles it to dispose of the water within that territory in any way it wishes, regardless of the consequences in Mexico” [48]. However, the US chose a more conciliatory approach, showing interest in catering to Mexico’s needs and historical grievances. In the 1906 agreement, the US agreed to deliver a fixed amount of water to Mexico, free of charge, to compensate for “past damages” after the completion of a storage dam fully paid for by the U.S. In return, Mexico would relinquish any claims of damage and past grievances [49,50]. In 1944, the two countries signed a subsequent agreement on the use of the Rio Grande, Colorado, and Tijuana Rivers with allocations to each country and modalities to handle water repayments during extreme droughts. Despite criticisms of the fixed volumetric allocations, the treaty’s adaptability through subsequent amendments known as “minutes” is noteworthy [51,52]. Significant amendments, such as Minute 319 and Minute 323, signed in 2012 and 2017, respectively, addressed water management during shortages and surpluses, environmental flows, conservation projects, water scarcity contingency plans, and climate change adaptation [53]. These amendments exemplify how evolving treaties can remedy initial shortcomings and adapt to changing circumstances, making them an exemplary practice in transboundary water management.

4.2. The Paraná River Basin: South America

The Paraná River basin is most exemplary for its co-owned infrastructure, benefit sharing, and regional economic integration schemes. A sub-basin of the larger La Plata River basin, the Paraná River is a transboundary river in South America shared by Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay [54]. In the 1960s, both Brazil and Paraguay (disputing over borders and resources at the time) planned to utilize the untapped hydropower potential of the Paraná River on their shared border [55,56]. The 1966 Iguaçu Act led to an exploratory study of the hydropower potential of the basin, resulting in the 1973 Itaipu Treaty and the construction of the Itaipu Dam, co-owned by Brazil and Paraguay. Argentina, which was not part of the project negotiations, initially contested the construction of the dam, but this was resolved through negotiations in 1979 [57]. The Itaipu dam began to operate in 1984 and is the third largest hydropower dam in the world with 14,000 MW of installed capacity [56]. While the Itaipu Dam has faced criticism for its costs and social and environmental impacts, it supplies 90% of Paraguay’s and 15% of Brazil’s electricity consumption [56]. The Itaipu Treaty evenly split the dam’s costs and energy output between Brazil and Paraguay, with a provision for selling unused energy to the other country [58]. Paraguay, a smaller country using only 15% of its share, sells the excess to Brazil, generating revenue and maximizing the shared water’s benefits, thereby deepening regional economic integration.

4.3. The Senegal and Orange-Senqu River Basins: Africa

The Senegal River basin is exemplary for capitalizing on moments of crisis, strong river basin organization, and benefit-sharing schemes. Located in western Africa, the basin is shared by Senegal, Mali, Mauritania, and Guinea. The “Great Sahel drought” that occurred in the late 1960s was a turning point for transboundary water management and cooperation in this basin [59]. The devastating impact of the drought brought countries together to efficiently utilize their shared resources and prevent future catastrophes in the region. This cooperation resulted in the creation of strong river basin organizations. The Senegal basin countries leveraged their shared language, colonial history under France, common issue of water scarcity, and homogeneity of economies to form a cohesive and effective river basin authority [59]. The Senegal River Basin Organization (OMVS) explicitly places the human right to water at the center of its transboundary water management, focusing on river basin developments to meet basic needs [47]. The Senegal River basin is also notable for its co-owned benefit-sharing schemes. The Manantali and Diama dams, funded with the help of external donors and co-owned by Mali, Senegal, and Mauritania, were originally planned to serve the navigation, hydropower, and irrigation needs of the three countries. Although these projects have faced criticism for not meeting expectations and for their negative social and environmental impacts [60,61], the Senegal River basin remains a prime example of how a strong river basin organization can facilitate multisectoral regional cooperation and benefit-sharing schemes.

The Orange-Senqu River basin is also exemplary for its strong river basin organization, its adoption of international water laws, and its benefit-sharing schemes. Shared by Botswana, Namibia, Lesotho, and South Africa, the Orange-Senqu River basin is lauded for its inclusive river basin organization which explicitly recognizes and abides by international water law principles. The Orange-Senqu River Commission (ORASECOM), established in 2000, includes all basin countries and explicitly recognizes international water laws such as the Helsinki Rules and the UN Watercourses Convention, in addition to regional regulations such as the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) protocol on shared watercourses [62]. The ORASECOM also implemented the River Basin Awareness Kit (RAK), a central repository of knowledge on different aspects of the basin, its people, water challenges, and governance developed through multistakeholder involvement [55]. Additionally, the basin features an exemplary benefit-sharing arrangement between South Africa and Lesotho: the Lesotho Highlands water project. In 1986, Lesotho and South Africa agreed on a water transfer project, where Lesotho would build a series of hydropower dams and tunnels to provide water to South Africa in exchange for royalties [55,63]. Leveraging Lesotho’s highland topography and abundant water resources, this arrangement minimizes water loss through evaporation and ensures economic water supply to South Africa while allowing Lesotho to benefit from hydropower generation and royalties. Furthermore, the positive involvement of external funders in supporting Lesotho’s infrastructure development underscores the constructive role that external actors can play in transboundary water management initiatives.

4.4. The Indus, Brahmaputra, and Mekong River Basins: Asia

The Indus River basin is often cited to exemplify the importance of strong treaties, the positive role of external support, and the importance of broader context in water management. The Indus River basin is an ancient water system containing several tributaries spanning India and Pakistan. Irrigation in the basin was intensified during the British rule of India and Pakistan, with intricate canal systems built through the unified territory. However, when India and Pakistan split to become independent countries in 1947, so did the canal systems, creating disputes between the countries [64]. An interim arrangement called the “Dominion Accord”, which required India to release water to Pakistan in return for annual payments, was reached. A permanent agreement was reached in 1960 when India and Pakistan signed the Indus treaty brokered by the World Bank. The broader political tension between the countries made integrated basin-wide water management improbable. Hence, a suboptimal yet workable approach of fragmented control of the rivers was adopted. Accordingly, the treaty gave exclusive use of the eastern rivers to India and the western rivers to Pakistan with some limitations [65]. Through World Bank funding, two dams were built on the river system to enhance the basin’s water supply. In addition, the treaty formed the permanent Indus Commission, which has been instrumental in dispute resolution in the basin. The Indus Water Treaty is often cited as an instance of a successful treaty, justified by the fact that it has survived multiple conflicts between the countries [55,66]. Its success underscores the constructive role of external actors, such as the World Bank, in supporting effective basin management. The basin also highlights the necessity of sub-optimal but pragmatic solutions in contexts where broader political tensions restrict comprehensive basin-wide collaboration.

The Brahmaputra River basin shared by Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, and India, illustrates effective multi-track diplomacy aimed at fostering cooperation across diverse scales [47,67,68]. Due to hydrological and geopolitical rivalries in the basin, it lacks both an inclusive regional collaboration platform and an inclusive treaty [58,59,60,61]. Moreover, the Brahmaputra basin suffers from the securitization of water, suspicion, mistrust, and lack of communication among the countries, which has made inclusive basin-wide treaties or regional platforms for collaboration difficult to achieve [69,70]. Multi-track diplomacy, i.e., diplomacy on multiple levels of society, including government, business, civil society, and citizens, was adopted in the basin as one avenue to work through these difficulties, with the “Brahmaputra Dialogue” being the most notable effort. The Brahmaputra Dialogue was initiated in 2013 to foster multi-track dialogue (track 1.5, 2, and 3), build relationships and trust, and help inform and complement official state-level (track 1) diplomacy [67,71]. This process has made progress in building trust, bringing together multiple viewpoints and stakeholders, highlighting overlooked perspectives, informing official state diplomacy, and enhancing the spirit of cooperation [68,71].

The Mekong River basin, shared by China, Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos, is exemplary of goodwill and collaboration and the positive role of external support. The Mekong River Commission (MRC) was formed by lower Mekong countries, i.e., Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos, in 1995. Although the MRC only governs the lower Mekong, China and Myanmar are “dialogue partners” in the commission. The Lancang Mekong Cooperation, an inclusive China-led initiative founded in 2016, is expected to be more suitable to cater to the needs of the basin [72]. However, the MRC has been crucial in preventing and managing conflicts, promoting sustainable management and development, cooperation, and information and benefit sharing, and fostering scientific analysis, technical cooperation, and communication among countries [73,74]. The long-standing support of the UN and the US since the 1950s has been instrumental in the formation of the MRC as well as the completion of important studies on the basin [74].

4.5. Jordan River Basin: The Middle East

The Jordan River basin exemplifies the importance of negotiations and the need to consider broader political dynamics and actors in transboundary water management. The Jordan River basin is shared by Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. Amid political tension between the countries, the Johnston Plan, a US-brokered plan for equitable water allocation of the Jordan River and its tributaries, was put forward in 1955 [75,76]. This plan aimed to unify prior allocation proposals by the US (the main plan), Egypt (the Arab plan), and Israel (the Cotton plan) with the incentive of funding for future development in the region by the US [75]. The Johnston allocation plan was devised purely based on the proportion of irrigable land of each riparian country within the basin and proposed a fixed volumetric allocation among Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, and Syria [76]. Even though the Johnston plan was agreed upon by the riparian countries, the plan was never ratified. The question of national sovereignty and the wider political tensions among Israel, Palestine, and the surrounding Arab states had direct implications on the water use discussion. The active involvement of Egypt and the exclusion of Iraq and Saudi Arabia is said to have helped the negotiations, while the lack of support from the Arab League was part of the reason the plan was never ratified [55,75]. Despite the challenges, the unified Johnston plan had some positive consequences in the basin. It led to multiple bilateral agreements in the basin (Jordan and Israel agreement, 1994; Jordan and Syria agreement; 1953 modified in 1987; Israeli–Palestinian Interim Agreement, 1993, 1995) [77,78]. The technical details of the plan, such as the volumetric allocations, are still honored and in use by individual countries [75,76]. The legal term “rightful allocation” was also coined to reconcile the demand for the recognition of their sovereignty and water rights by Palestine and Jordan, as well as the demand for “allocation” by Israel in the bilateral agreement between Jordan and Israel signed in 1994 [78].

4.6. The Danube and the Rhine River Basins: Europe

The Danube River basin is exemplary for its harmonized policies across multiple scales and participatory approaches in transboundary water management. Shared by 19 countries in Europe, the Danube River basin is the world’s most international river in terms of the number of riparian countries and covers nearly 10% of the European landmass [79]. It flows through countries with significant economic and political disparities. Economically, the wealthier countries in the basin have GDPs 14 times higher than the less affluent countries. Politically, the riparian countries were divided between the eastern vs. western blocks until the early 1990s. Despite a large number of diverse riparian countries, the Danube basin is exemplary for embodying a participatory approach and showcasing an ability to coordinate policies across scales, ensuring national, basin-wide, as well as supranational, directives on water align [55]. The International Commission on the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR), established in 1998, coordinates the implementation of the supranational European Water Framework directive across multiple countries. In addition, it handles water management issues across the basin (pollution, flooding, accident management, river restoration) through public participation [55,79]. The Danube illustrates the importance of the broader political context for successful transboundary water management. The ICPDR was formed only after the political divide between eastern and western Europe had softened. The formation of the EU and the disintegration of the Soviet Union also significantly supported the harmonization of water policies across the basin [80]. It is also important to note that even though not all riparian countries of the Danube are members of the EU, there was a political willingness to accede to the stringent directives of the EU Water Framework directive.

The Rhine River basin is another example of harmoniously working across scale and effective participatory management. The Rhine River basin consists of nine countries across Europe. The Rhine, once labeled as “the sewer of Europe”, suffered from extreme pollution and the degradation of the aquatic ecosystem to the point that salmon was extinct in the river [10,81]. The International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) was instrumental in the cleanup, rehabilitation, and later flood protection efforts across the basin. The ICPR developed a monitoring strategy and a comprehensive integrated management strategy for the Rhine. Building confidence and trust, as well as political willingness, was necessary to bring together these basin countries which were on opposite sides during World War II [81,82]. Public pressure was also instrumental in pushing states to act, especially after disasters such as the Sandoz fire and chemical spill of 1986, which highlighted the need to urgently rehabilitate the Rhine [81,83]. The success of the ICPR and the harmonious and participatory approach embodied in the Rhine are evident in the fact that the pollution reduction targets were achieved by 2000, salmon returned to the river after 50 years, and the Rhine became one of the cleanest rivers in Europe. The ICPR also evolved to address more timely issues of the basin such as flooding, capitalizing on the success of the long history of cooperation across countries [83]. A summary of the case studies, along with core lessons learned from each, is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of best practices and lessons from basins across the world.

5. Reflections on the Nile

The experiences presented above show some commonalities in elements that lead to successful and unsuccessful transboundary water management. An inclusive and strong river basin organization, trust and mutual respect between riparian countries, open dialogue, reciprocal data sharing, harmonized policies across scale, and the value of capitalizing on moments of crisis or conflict situations are recurring themes in successful transboundary water management. On the other hand, the exclusion of key players (riparian and non-riparian actors) from basin-wide discussions, discounting the impact of wider (political) context in water use discussions, fixed water allocations and rigid treaties, and the negative influence of external actors jeopardize success in transboundary water management.

In the context of the Nile basin, there are distinctive challenges, including deep-seated mistrust, unjust historical water use arrangements, and influence from external actors. Overcoming these challenges necessitates specific actions in building trust, creating equitable water use frameworks, establishing a robust, inclusive river basin organization, as well as considering the role of external actors and broader political context. Below, we elaborate on these themes and draw insights from other transboundary basins that can provide valuable guidance.

5.1. Trust Building

Centuries of tension over Nile water use, compounded by colonial-era inequities and external influences, have caused deep mistrust among basin countries. Trust building is thus a major pre-requisite for transboundary water management interventions. This process begins with acknowledging historical injustices and taking steps to rectify the arrangements that underpin these inequities. The initiative of the US and Mexico in addressing historical injustices serves as a model, demonstrating the importance of confronting history to pave the way forward. Similarly, the example of the Rhine and Danube River basins, where countries with histories of conflict and differing political ideologies came together for successful basin management, offers hope that the Nile basin countries can achieve the same.

Trust building in the Nile basin needs to occur at multiple scales. While state-level diplomacy is understandably the primary focus, grassroots initiatives involving citizen groups, academics, and NGOs can foster mutual understanding among people with a tense history and garner support for collaborative efforts. The approach exemplified in the Brahmaputra basin, which recognized existing barriers to basin-wide collaboration and adopted multi-track diplomacy for trust building as an integral part of transboundary water management, provides an apt example for the Nile.

5.2. Equitable and Sustainable Water Use Frameworks

The current water use agreements in the Nile basin pose significant obstacles to effective transboundary water management. These agreements often lack alignment with international water law principles and, in some cases, undermine national sovereignty. The fixed water allocations and rigid treaties also do not cater to equitable or sustainable water use in the basin. As such, the basin needs to move towards equitable and sustainable adaptive water use practices. A pre-requisite for such water frameworks is the acknowledgment that all Nile basin countries have a fair share of the Nile water. Then, it follows that the current water use allocation schemes do not cater to this basic principle and, hence, cannot have a place in current and future water use discussions. Terms such as historical rights, natural rights, and established shares should not dictate negotiations in the Nile basin. The acknowledgment of equitable rights is a running theme in all the exemplary practices featured. The example of the US acknowledging Mexico’s concern and respecting Mexico’s right in the Rio Grande River basin as well as the conciliatory approach exemplified in the Jordan River basin in coming up with the compromise terminology of “rightful allocation” to satisfy Israel’s demand for allocation and the Palestinian demand for sovereignty and rights are instructive here.

The problem with fixed water allocation treaties, especially considering growing demands and climate change uncertainties, is evident in multiple river basins including the Ganges and the Colorado River basins [84,85]. These examples should serve as cautionary tales for the Nile basin. Treaties can help to foster transboundary water management, especially in politically unstable and low-income regions such as the Nile basin [86,87,88]. Treaties, however, need to be flexible and evolving to adapt to and accommodate changing circumstances. Flexibility can be built into otherwise rigid treaties by opting for frameworks requiring periodic agreements, short-lifespan treaties with the option of renewal and termination, or allowing for special provisions for unforeseen circumstances [88]. The US–Mexico experience of adapting treaties with minutes is a good example of an adaptive treaty. Ideally, the future of water use in the Nile basin should shift towards cooperative and adaptive frameworks of decision-making under uncertainties based on robust science and good data instead of rigid treaties [89]. There are exemplary practices of benefit sharing and co-owned infrastructures from the Senegal, Parana, and Orange-Senqu River basins, which capitalized on location efficiency to maximize benefits, reduce loss, and ensure collaborative, economic, and sustainable use of shared waters. While the Nile case should certainly learn from these experiences, it is worth noting that benefit-sharing schemes require a high level of trust and goodwill among riparians, stability in the basin, and the willingness to moderate rigid positions and focus on shared interests to maximize benefits. The Nile basin is struggling with entrenched positionalities, a lack of trust and goodwill, and political volatility. The basic prerequisite for benefit sharing, i.e., the acknowledgment of equitable rights of all basin countries to the shared river, is still a major issue in the Nile basin. As such, the Nile basin needs to work on trust building and the acknowledgment of the equitable rights of all basin countries before benefit sharing and co-owned infrastructure can become feasible options in the basin.

5.3. Strong River Basin Organization

An inclusive and strong river basin organization was one of the common aspects of many successful transboundary river basins. These organizations are instrumental in facilitating data sharing, trust building, harmonizing policies across scales, and fostering sustainable and collaborative approaches. Examples such as the Orange-Senqu and the Senegal River basins highlight how strong river basin organizations enforce international principles and help navigate crises effectively. In the Danube and Rhine River basins, these organizations have demonstrated their effectiveness in harmonizing policies and achieving tangible improvements. Similarly, the Mekong River Commission (MRC), despite its limited jurisdiction, has played a critical role in sharing data and providing scientific and technical support across the basin. The Nile basin stands to benefit significantly from a similar strong river basin organization. This role is currently played by the Nile Basin Initiative, an interim organization that is supposed to transition to the Nile River Basin Commission after the ratification of the CFA [46]. This is further impetus for the Nile basin countries to ratify the CFA.

5.4. Role of External Actors

External actors play a pivotal but complex role in transboundary water management, as illustrated by various case studies. The Indus Treaty and Lesotho Highlands projects exemplify how external support can facilitate cooperation. Conversely, the Jordan River basin highlights both the constructive and detrimental impacts of external involvement.

The Nile basin needs the support of external actors; however, historical interventions by external actors have often been one-sided, favoring downstream interests and leading to mistrust among basin countries. Colonial-era treaties, designed to benefit colonial powers, still influence the basin today, fostering unilateral and unsustainable development. Financial donors like the World Bank, IMF, US, and EU have historically been cautious about funding water projects in upstream Nile countries despite the hydrological advantages and economic benefits due to concerns about upsetting relations with Egypt [90]. In contrast, the Cold War political economy was instrumental in the funding and construction of the High Aswan Dam (HAD) “a technically inferior option adopted to control the Nile because the colonial alternatives, based on infrastructure in Sudan, Ethiopia and Uganda, would undermine Egypt’s sovereignty” [91]. Because of its location in the desert, the HAD loses 10–20 BCM of water annually to evaporation, a rather significant amount in a water-scarce basin [92,93]. Such instances demonstrate how the involvement of external actors in the basin is often colored by political more than hydrological considerations. Recent interventions by regional and global funders and actors (African Union, the Arab League, the EU, the US, IMF, World Bank, etc.) have also been deemed partisan and unhelpful either by upstream or downstream Nile basin countries. This makes the role of external actors in the basin a sensitive matter.

Ideally, external actors would engage in the basin with sensitivity to historical and current geopolitical contexts. But the Nile basin must contend with the impossibility of detaching the geopolitical interests and self-interest of external actors from their support in the short term. This should be an incentive for the basin to move towards self-sufficiency in the long term through co-owned and collaborative projects funded by the riparian countries, similar to the approach seen in the Paraná River basin. Thus, while external support remains critical, achieving sustainable transboundary water management in the Nile basin requires balancing external involvement with local autonomy and collaborative self-sufficiency among basin countries.

5.5. Broader Political Context

Experiences in the Jordan, Indus, Brahmaputra, the Danube, and the Rhine rivers demonstrate the importance of addressing the wider political context between riparian countries alongside water use discussions. This approach is also needed in the Nile. Recent unrest within and among Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan, and South Sudan and the impact on water use discussions can exemplify the impact of political context in water use discussions. The political tension between the countries can make integrated basin-wide management improbable. Hence, accepting sub-optimal yet workable solutions might be necessary for the Nile basin as was the case for the Indus River basin. Though the basin scale is often recommended as the preferred working scale from an integrated water use perspective, volatile (political) basin dynamics can make working at the basin scale difficult. Alternatively, sub-basins and “problem sheds” have been proposed as a fragmented yet more pragmatic operational scale, especially in volatile basins [94,95,96]. Given the broader political and historical context in the Nile basin, moving away from the basin scale and considering the sub-basin scale might therefore be a suboptimal yet necessary pathway for the Nile basin to consider.

There are numerous other best practices that were not highlighted in this study. For instance, the exemplary practice from the Yukon River basin shared by the US and Canada of incorporating Indigenous knowledge with modern science in basin management is noteworthy for the Nile [97]. There are also multiple basins in Europe and Asia, such as the Meric, the Kura Aras, and the Baikal River basins, notable for their reciprocal data sharing and joint fact-finding efforts as well as the adoption of holistic, sustainable, and adaptive water management approaches [47]. The Mesilim treaty, signed in 2550 BC, on the shared utilization of the Tigris River between Lagash and Umma, two city-states in ancient Mesopotamia, is an exemplary treaty that modeled benefit sharing, payment for water services, collaborative water use, and the positive role of regional actors [98].

It should be noted that this study is not an exhaustive examination of transboundary water management practices. Numerous other river basins exhibit exemplary practices that were not covered in our review. Our analysis was limited to the examples selected based on our specific methodology. Additionally, due to the focus of this paper, we emphasized lessons particularly relevant to the Nile. However, there are many general and contextual lessons to be drawn from both the successes and failures of the case studies presented, which can be applied to other river basins. Given the vast number of transboundary river basins and the common factors contributing to both successful and unsuccessful practices, future research could benefit from developing a comprehensive matrix to systematically assess experiences based on a structured evaluation framework.

6. Conclusions

Learning from the experiences of other river basins can help navigate the complexity of transboundary water management. While there are many lessons to be drawn from various transboundary waters, the success of best practices depends on tailoring them to the specific context of each basin. To that end, we explored global practices in transboundary water management to draw contextual lessons for the Nile River basin.

The case studies reviewed highlighted common elements of successful transboundary water management, including strong and inclusive river basin organizations, trust and mutual respect between riparian countries, open dialogue, reciprocal data sharing, harmonized policies, and leveraging crises for cooperation. Conversely, pitfalls include excluding key players, ignoring broader political contexts, fixed water allocations, rigid treaties, and negative external influences.

The Nile basin faces unique challenges such as deep-seated mistrust, colonial-era water use arrangements, and significant external-actor influence. Addressing these requires targeted interventions in trust-building, developing flexible and equitable water use frameworks, and establishing a strong and inclusive river basin organization. Key recommendations include acknowledging and addressing past injustices, fostering trust through multi-track diplomacy, adopting adaptive and cooperative water use frameworks, and involving all stakeholders. The role of external actors should be balanced and contextually aware, and given the broader volatile political context in the basin, it might be necessary to consider sub-optimal solutions and scales as potential compromises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.D., A.M.M., B.B.K., S.D. and E.P.A.; Writing—Original draft preparation, M.M.D.; Writing—review and editing, M.M.D., A.M.M., B.B.K., S.D. and E.P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support from Florida International University’s Dissertation Evidence Acquisition (DEA) fellowship and Schlumberger Foundation’s Faculty for the Future fellowship (AWD000000016815).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNECE. Handbook on Water Allocation in a Transboundary Context; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-11172-73-7. [Google Scholar]

- College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University. Transboundary Freshwater Spatial Database. Available online: https://transboundarywaters.ceoas.oregonstate.edu/transboundary-freshwater-spatial-database (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- IGRAC. The Global Groundwater Information System (GGIS). Available online: https://ggis.un-igrac.org/view/tba/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- UN-Water. Transboundary Waters Facts; UN-Water: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Global Water Partnership. Transboundary Water Cooperation. 2020. Available online: https://www.gwp.org/en/we-act/themesprogrammes/Transboundary_Cooperation/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arjoon, D.; Tilmant, A.; Herrmann, M. Sharing water and benefits in transboundary river basins. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 2135–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochmann, M.; Gleditsch, N. Shared rivers and conflict—A reconsideration. Political Geogr. 2012, 31, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansink, E.; Weikard, H.-P. Contested water rights. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2009, 25, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitoun, M.; Goulden, M.; Tickner, D. Current and future challenges facing transboundary river basin management. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2013, 4, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoa, R.B. The United Nations Watercourses Convention on the Dawn of Entry into Force. Vanderbilt J. Transnatl. Law 2021, 47, 1321. [Google Scholar]

- Varady, R.G.; Albrecht, T.R.; Modak, S.; Wilder, M.O.; Gerlak, A.K. Transboundary Water Governance Scholarship: A Critical Review. Environments 2023, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. UN Watercourses Convention. Available online: https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/water_cooperation_2013/un_watercourses_convention.shtml (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Salman, S.M.A. Equitable and Reasonable Utilization and the Obligation Against Causing Significant Harm—Are they Reconcilable? AJIL Unbound 2021, 115, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, S.M.A. The Helsinki Rules, the UN Watercourses Convention and the Berlin Rules: Perspectives on International Water Law. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2007, 23, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, S.C. The Law of International Watercourses; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice, M. Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses ARTICLES. Leiden J. Int. Law 1997, 10, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema, A.E. The United Nations Watercourses Convention from the Ethiopian Context: Better to Join or Stay Out? Haramaya Law Rev. 2015, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses; UN: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Boisson de Chazournes, L.; Tignino, M. International Water Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.; Winterman, K. Models and Mandates in Transboundary Waters: Institutional Mechanisms in Water Diplomacy. Water 2022, 14, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oregon State University. International River Basin Organization Database. Available online: https://transboundarywaters.dev.oregonstate.edu/international-river-basin-organization-database (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Earle, A.; Wouters, P. Implementing transboundary water cooperation through effective institutional mechanisms exploring the legal and institutional design dimensions of selected african joint water institutions: Creative lessons for global problems? J. Water Law 2014, 24, 100–114. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeier, S. The institutional design of river basin organizations—Empirical findings from around the world. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2015, 13, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägerskog, A. Transboundary Water Management—Why It Is Important and Why It Needs to Be Developed. In Free Flow—Reaching Water Security Through Cooperation; UNESCO Publishing and Tudor Rose: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sara, J.J.; Borgomeo, E.; Jagerskog, A. Measuring Success in Transboundary Water Cooperation: Lessons from World Bank Engagements. 2021, World Bank. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/water/measuring-success-transboundary-water-cooperation-lessons-world-bankengagements#:~:text=There%20are%20many%20of%20these,any%20type%20of%20cooperative%20arrangement (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Sullivan, C.A. Planning for the Murray-Darling Basin: Lessons from transboundary basins around the world. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2014, 28, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, M.E.; Neir, A.M.; Klise, G.T. Dynamics of Transboundary Groundwater Management: Lessons from North America. In Governance as a Trialogue: Government-Society-Science in Transition; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albergaria, R.; Fidelis, T. Transboundary EIA: Iberian experiences. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2006, 26, 614–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CADRI. Good Practices on Transboundary Water Resources Management and Cooperation; CADRI: Toronto, ON, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture—Systems at breaking point. In Synthesis Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- NBI. State of the Basin; NBI: Kamapala, Uganda, 2021; ISBN 978-9970-444-05-2.

- Wheeler, K.G.; Jeuland, M.; Hall, J.W.; Zagona, E.; Whittington, D. Understanding and managing new risks on the Nile with the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senay, G.B.; Velpuri, N.M.; Bohms, S.; Demissie, Y.; Gebremichael, M. Understanding the hydrologic sources and sinks in the Nile Basin using multisource climate and remote sensing data sets. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 8625–8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBI. The Nile Basin Water Resources Atlas; NBI (New Vision Printing and Publishing): Kamapala, Uganda, 2016; ISBN 978-9970-444-02-1.

- Erlich, H. The Struggle over the Nile: Egyptians and Ethiopia; Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies at Tel-Aviv University: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tayia, A.; Barrado, A.R.; Guinea, F. The evolution of the Nile regulatory regime: A history of cooperation and conflict. Water Hist. 2021, 13, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M. The Nile Basin Cooper the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement: The Beginning of the End of Egyptian Hydro-Political Hegemony. J. Environ. Sustain. Law 2011, 18, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, Y.; Deribe, M.M.; Melesse, M.B.; Abazeed, A.; Babekir, A.; Moghraby, N. Songs and Poems of the Nile: When words mix with water and politics. In People and Water in Egypt; Nour, A., Ed.; Safsafa Publishing House: Giza, Egypt, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Deribe, M.M.; Berhanu, B. Conceptualization of Equitable and Reasonable Water Sharing in the Nile Basin with Quantification of International Transboundary Water-Sharing Principles. In Nile and Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam: Past, Present and Future; Melesse, A.M., Abtew, W., Moges, S.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ferede, W.; Abebe, S. The Efficacy of Water Treaties in the Eastern Nile Basin. Afr. Spectr. 2014, 49, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimbazi, E. The impact of colonial agreements on the regulation of the waters of the River Nile. Water Int. 2010, 35, 718–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK and Egypt. Exchange of Notes between Her Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom and the Egyptian Government on the Use of Waters of the Nile for Irrigation; Cairo, Egypt, 1929. Available online: https://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/documents/regionaldocs/Egypt_UK_Nile_Agreement-1929.html (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Egypt and Sudan. Agreement (with Annexes) for the Full Utilization of the Nile Waters; Cairo, Egypt, 1959. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20453/volume-453-I-6519-English.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Kimenyi, M.S.; Mbaku, J.M. The Nile Waters Agreements: A Critical Analysis, in Governing the Nile River Basin: The Search for a New Legal Regime; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- NBI. Agreement on the Nile River Basin Cooperative Framework; NBI: Entebbe, Uganda, 2010.

- UNW-AIS. Good Practices in Transboundary Water Cooperation. 2023. Available online: https://www.ais.unwater.org/ais/TPA_Transboundary/map/# (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- McCaffrey, S.C. The Harmon Doctrine One Hundred Years Later: Buried, Not Praised. Nat. Resour. J. 1996, 36, 965. [Google Scholar]

- US and Mexico. Convention between the United States and Mexico Equitable Distribution of the Waters of the Rio Grande; International Boundary, and Water Commission: El Paso, TX, USA, 1906.

- Paddock, W.A. The Rio Grande Convention of 1906: A Brief History of an International and Interstate Apportionment of the Rio Grande. Denver Law Rev. 1999, 77, 287. [Google Scholar]

- Umof, A.A. An Analysis of the 1944 U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty: Its Past, Present, and Future. Environ. Law Policy J. Univ. Calif. Davis 2008, 32, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Schiff, D.M. Rollin’, Rollin’, Rollin’ on the River: A Story of Drought, Treaty Interpretation, and Other Rio Grande Problems. Indiana Int. Comp. Law Rev. 2003, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Boundary and Water Commission IBWC US and Mexico, Minute 319. 2012. Available online: https://www.ibwc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Minute_319.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- FAO AQUASTAT. Transboundary River Basin Overview—La Plata; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, A.; Jägerskog, A.; Öjendal, J. (Eds.) Transboundary Water Management Principles and Practice; Earthscan: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Global Infrastructre Hub. Itaipu Hydroelectric Dam. 2020. Available online: https://www.gihub.org/connectivity-across-borders/case-studies/itaipu-hydroelectric-dam/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Schenoni, L. Regional Power Transitions: Lessons from the Southern Cone; Working Paper No. 293; German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA): Hamburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brazil and Paraguay. Itaipu Treaty. 1973. Available online: https://itaipu.energy/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Treaty_of_Itaipu.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Bolognesi, T.; Brethaut, C.; Sangbana, K.; Tignino, M. Transboundary Governance in the Senegal and Niger River Basins: Historical Analysis and Overview of the Status of Common Facilities and Benefit Sharing Arrangements; University of Geneva, Geneva Water Hub: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Diessner, C. Dam Complications in Senegal: How River Dams May Hurt More than Help Vulnerable Populations in Water-Stressed Regions. J. Environ. Sustain. Law 2012, 19, 247. [Google Scholar]

- Bosshard, P. A Case Study on the Manantali Dam Project (Mali, Mauritania, Senegal). 1999. Available online: https://archive.internationalrivers.org/resources/a-case-study-on-the-manantali-dam-project-mali-mauritania-senegal-2011 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- ORASECOM. Regional and International Agreements. Available online: https://orasecom.org/regional-and-international-agreements-2/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Water Technology. Net. Lesotho Highlands Water Project. Available online: https://www.water-technology.net/projects/lesotho-highlands/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Bauer, P. Indus Waters Treaty. 2023. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/event/Indus-Waters-Treaty (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- World Bank. Fact Sheet: The Indus Waters Treaty 1960 and the Role of the World Bank. 2018. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/sar/brief/fact-sheet-the-indus-waters-treaty-1960-and-the-world-bank (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Uprety, K.; Salman, S.M.A. Legal aspects of sharing and management of transboundary waters in South Asia: Preventing conflicts and promoting cooperation. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2011, 56, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, Y.; Hill, D.; Aich, D.; Huntjens, P.; Swain, A. Multi-track water diplomacy: Current and potential future cooperation over the Brahmaputra River Basin. Water Int. 2018, 43, 642–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, A. Water diplomacy as an approach to regional cooperation in South Asia: A case from the Brahmaputra basin. J. Hydrol. 2018, 567, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, A.; Vij, S.; Zulfiqur Rahman, M. Powering or sharing water in the Brahmaputra River basin. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2018, 34, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.M.; Varis, O. Integrated water management of the Brahmaputra basin: Perspectives and hope for regional development. Nat. Resour. Forum 2009, 33, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, A.; Vij, S. Treaties can be a non-starter: A multi-track and multilateral dialogue approach for Brahmaputra Basin. Water Policy 2018, 20, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junlin, R.; Ziqian, P.; Xue, P. New transboundary water resources cooperation for Greater Mekong Subregion: The Lancang-Mekong Cooperation. Water Policy 2021, 23, 684–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J. Mekong River Committee’s Role in Mekong Water Governance. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Public Administration, Cape Town, South Africa, 31 October–2 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kittikhoun, A.; Staubli, D. Water diplomacy and conflict management in the Mekong: From rivalries to cooperation. J. Hydrol. 2018, 567, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.T.; Newton, J.T. Case Study of Transboundary Dispute Resolution: The Jordan River Johnston Negotiations 1953–1955; Yarmuk Mediations 1980s; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Talozi, S.; Altz-Stamm, A.; Hussein, H.; Reich, P. What constitutes an equitable water share? A reassessment of equitable apportionment in the Jordan–Israel water agreement 25 years later. Water Policy 2019, 21, 911–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (a.k.a. “Oslo II”); UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fanack Water. Shared Water Resources in Jordan. 2022. Available online: https://water.fanack.com/jordan/shared-water-resources-in-jordan/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- ICPDR. The Danube River Basin: Facts and Figures; ICPDR: Vienna, Austria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Krengel, F.; Bernhofer, C.; Chalov, S.; Efimov, V.; Efimova, L.; Gorbachova, L.; Habel, M.; Helm, B.; Kruhlov, I.; Nabyvanets, Y.; et al. Challenges for transboundary river management in Eastern Europe-three case studies Challenges for transboundary river management in Eastern Europe-three case studies. Die Erde 2018, 149, 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Wülwer-Leidig, A.; Gangi, L.; Stötter, T.; Braun, M.; Schmid-Breton, A. Transboundary Cooperation and Sustainable Development in the Rhine Basin. In Achievements and Challenges of Integrated River Basin Management; InTech: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mostert, E. International co-operation on Rhine water quality 1945–2008: An example to follow? Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2009, 34, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, J.S. The evolution of Rhine river governance: Historical lessons for modern transboundary water management. Water Hist. 2017, 9, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, C.V.; Sheikh, P.A.; Hite, K. Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role; C.R. Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, K.S.; Islam, Z.; Navera, U.K.; Ludwig, F. A Critical Review of the Ganges Water Sharing Arrangement. Water Policy 2019, 21, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, C.; Nagabhatla, N. Designing Transboundary Agreements: What Can We Learn from Existing Water Treaties? The Water Network, 2016. Available online: https://mission-ganga.thewaternetwork.com/blog/catherine-chisholms-blog/designing-transboundary-agreements-what-can-we-learn-from-existing-water-treaties-1xasxtCqxbrMtesinYOEXg (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Dinar, S.; Katz, D.; De Stefano, L.; Blankespoor, B. Do treaties matter? Climate change, water variability, and cooperation along transboundary river basins. Political Geogr. 2019, 69, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, S.C. The need for flexibility in freshwater treaty regimes. Nat. Resour. Forum 2003, 27, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulden, M.; Conway, D.; Persechino, A. Adaptation to climate change in international river basins in Africa: A review/Adaptation au changement climatique dans les bassins fluviaux internationaux en Afrique: Une revue. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2009, 54, 805–828.86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, A. Impacts of Global Change on the Nile Basin: Options for Hydropolitical Reform in Egypt and Ethiopia; IFPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R. History, hydropolitics and the Nile: Myth or reality. In The Nile: Sharing a Scarce Resource: A Historical and Technical Review of Water Management and of Economical and Legal Issues; Howell, P.P., Allan, J.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Abou El-Magd, I.H.; Ali, E.M. Estimation of the evaporative losses from Lake Nasser, Egypt using optical satellite imagery. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2012, 5, 133–146.89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elba, E.; Farghaly, D. Modeling High Aswan Dam Reservoir Morphology Using Remote Sensing to Reduce Evaporation. Int. J. Geosci. 2014, 5, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Woodhouse, P.; Muller, M. Water Governance—An Historical Perspective on Current Debates. World Dev. 2017, 92, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, A. The Nile River Basin Initiative: Too Many Cooks, Too Little Broth. SAIS Rev. 2002, 22, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischhendler, I.; Feitelson, E. Spatial adjustment as a mechanism for resolving river basin conflicts: The US-Mexico case. Political Geogr. 2003, 22, 557–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council (Y.R.I.-T.W.C). Yukon River Watershed Plan. 2013. Available online: https://www.yritwc.org/yr-watershed-plan (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Sand, P.H. Mesopotamia 2550 B.C.: The Earliest Boundary Water Treaty. Glob. J. Archeol. Anthropol. 2018, 50, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).