Abstract

Water governance and ecosystem function in the Canadian prairies are in a state of crisis. Compounding this crisis, and adding complexity, is the relationship between the water governance authority of the state with Canada’s First Peoples. Meaningful engagement of Indigenous peoples in water governance is a necessary requisite to effective water management. This research characterizes the extent and depth of Indigenous engagement in watershed planning in the province of Manitoba, Canada, and examines the degree to which Indigenous rights are incorporated in that engagement. To do so, we analyze evidence of First Nation people’s inclusion in water governance, planning, and management processes. We conducted latent and manifest content analyses of watershed plans to identify the themes and frequency of content related to First Nations and Métis engagement and triangulated results with key informant semi-structured interviews and document reviews of water governance policies and legislation. Overall, we find that Indigenous engagement in Manitoba water governance has increased over time but is still lacking adequate recognition and implementation of Aboriginal and Treaty rights.

1. Introduction

Dams, drainage, and land cover change have altered watersheds across Canada [1,2,3]. Federal and provincial approaches to water and land management have benefited industries, settlers, and some First Nations. Yet, settler colonial water governance has also produced disproportionate impacts on Indigenous peoples, who are often excluded from the decisions that most affect their rights and interests. Scholars have described this as environmental or water injustice [4,5,6,7]. The roots of these injustices are in the structures and processes of settler colonialism.

Starting with Canada’s “highly decentralized federation” [8] (p. 277), government responsibilities and jurisdiction over water and the environment are divided exclusively between provincial and federal governments and within ministries and agencies, neglecting or overlooking Indigenous laws, rights, and responsibilities [9]. Decentralization not only enables contextualized approaches to, and innovation in, water and ecosystem management but also drives fragmentation. The result is a patchwork approach to water management across Canada [10], with inconsistent and uneven inclusion and engagement of Indigenous people [9,11,12,13,14].

For our purposes, water governance “[consists] of the processes and institutions by which decisions that affect water are made” [15] (p. 7); watershed planning is a mechanism of water governance; and Indigenous participation in watershed planning processes is an example of Indigenous engagement—of Indigenous peoples by government, and by Indigenous peoples with government institutions and processes. First Nations and Métis people who want to actively fulfill their traditional water stewardship responsibilities beyond reserve borders have to navigate through, participate in, and actively contest the processes and structures of water governance in Canada [16,17,18]. These interactions may be formal or informal; our focus is on formal participation in watershed planning.

We can examine a subset of these formal interactions recorded in watershed plans and related documents. Prior studies have examined First Nations engagement in watershed planning in Alberta [19] and Saskatchewan [20]. This study analyzes Indigenous engagement in the prairie provinces by describing how Indigenous engagement has been practiced in provincial water governance in Manitoba, Canada (Figure 1). First, we situate the study in the broader context of water-related Indigenous–Settler relations in Canada and the province of Manitoba. Second, we describe the methods and data sources. Third, we describe the results of our thematic analysis. Last, we conclude with a discussion and recommendations for policy, practice, and research.

Figure 1.

Map of Canada depicting the location of the province of Manitoba.

1.1. Indigenous Engagement and Canadian Water Management

Indigenous–state relations in Canada are complex, contested, and contingent. While some Indigenous peoples—such as those in the northern territories and parts of British Columbia—are party to contemporary treaties, settlements, and agreements that articulate clearly the rights and responsibilities of the parties involved, other Indigenous peoples in Canada are not [9,21]. Most First Nations in the Canadian prairies are party to historic treaties with the Crown (Canada in lieu of the British monarchy), where rights and responsibilities are not explicitly described in contemporary legal terminology [22,23,24]. Yet, historic treaties are still influential in structuring the relationships between First Nations and both federal and provincial governments.

The lack of historic treaties in most of British Columbia and the north means that the courts recognize Indigenous land as unceded, and First Nations have negotiated modern land claims that secure Indigenous representation in resource and water management [25,26,27,28]. Northern populations are typically comprised of a greater proportion of Indigenous peoples, often forming a majority. Through voting and greater representation in environmental management institutions, their values and interests drive territorial government decision-making more so than in the provinces. Neither of these circumstances apply in the prairies.

Settler governments and scholars argue that historic treaties were primarily about land cession and claim that with the 1930 Natural Resources Transfer Agreements, the federal government transferred sole administrative jurisdiction of lands and resources to the provinces [24,29]. Cession, according to settler governments, means that First Nations gave up any claims to their Aboriginal title in exchange for benefits recorded in the treaty, and in some cases verbal promises as well [30]. However, the consultations associated with Aboriginal and Treaty rights fall short of co-governance or co-management seen in British Columbia and the north; co-governance arrangements are the types of engagements expected by First Nations as commensurate with being treaty partners [25,26,31,32]. First Nations also contest and resist the unilateral interpretation of historic treaties as cession, instead affirming their intent to share the land [22,23]. The limitations on the recognition of rights and responsibilities flow from the structures and processes of settler colonization.

Settler colonization is a “complex social formation…[with] continuity over time”, and its nature as “a structure rather than an event” [33] (p. 390) implicates settler institutions and systems [9]. Colonization has produced inequalities in power, security, and well-being by privileging Western knowledge systems and prioritizing hegemonic settler values and interests [34,35,36,37]. Even with international support through instruments such as the UNDRIP [38], Indigenous rights and responsibilities in Canada are unevenly recognized, respected, or implemented by federal and provincial governments.

The quality and extent of Indigenous engagement fluctuate according to prevailing political ideologies, the state of the economy, and national or regional social sentiment [39,40,41]. While the province of British Columbia has passed legislation to implement the UNDRIP, other provinces have not, instead skirting questions of Aboriginal title and free, prior, informed consent by reasserting jurisdiction through legislation and repeatedly contradicting First Nations’ interpretations of treaty agreements. This dual strategy of avoidance and denial extends to local levels in the context of water management and planning.

Provincial and federal governments create or recognize entities and authorize them to conduct and implement watershed or water resources planning. While most provinces have discursively adopted an integrated approach to management, the details of laws, policies, and institutions for implementing it vary [42]. There are, however, common themes. Indigenous peoples are often classified as stakeholders [8,43] and are allowed to participate in planning and management alongside other interested groups such as industry, local governments, and non-government organizations [44,45]. These processes and institutions of water management on the prairies are structurally inadequate for the full recognition of Aboriginal and Treaty rights [4,9,46,47,48]. Given the role of law and policy in structuring the inclusion of Indigenous peoples in water governance, we next describe how Manitoba’s approach to Indigenous engagement has changed over time.

1.2. Water Management and Planning in Manitoba

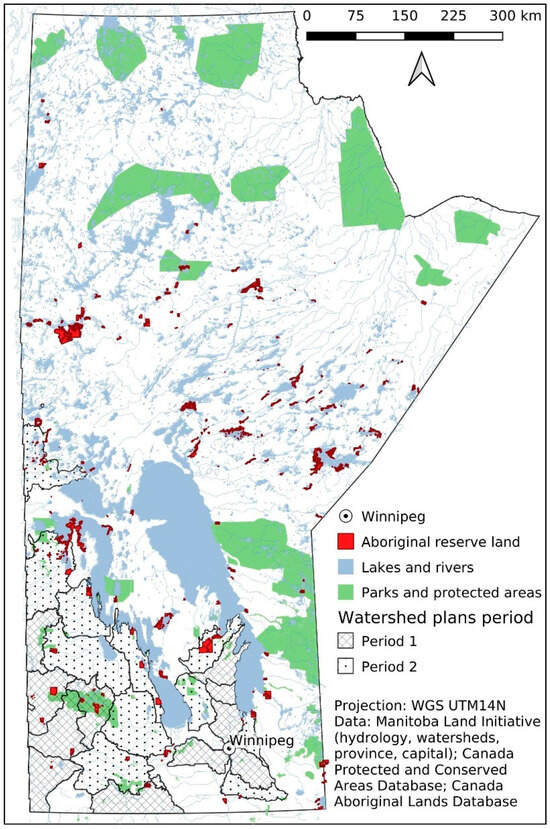

Before exploring the institutional context of Manitoba’s water governance, we briefly describe its hydrography. The province of Manitoba is wholly within the Hudson Bay drainage basin, with significant flows, lakes, and reservoirs throughout. Several large water bodies—Cedar Lake, Lake Manitoba, Lake Winnipegosis, and Lake Winnipeg—cover much of the southern half of the province (see Figure 2). These lakes are fed by the Saskatchewan and Assiniboine Rivers from the west and Red River from the south. Lake Manitoba flows into Lake Winnipeg, which then flows through the Nelson River into Hudson Bay. Also flowing into Hudson Bay are the Churchill River, from Saskatchewan through northern Manitoba, and the Hayes and Gods River, draining the central-eastern region.

Figure 2.

Map of Manitoba, Canada, depicting extents and distribution of Aboriginal reserve land, conserved and protected areas, surface water, and watersheds with plans.

According to the provincial power generator, five major river systems in the province have also been modified to produce electricity: an extensive series of reservoirs and dams are used to regulate flows for 16 hydroelectric generating stations. This power is used within Manitoba and exported to other provinces and the United States. Historically, dams in the north were designed, constructed, and operated without consideration of impacts on northern First Nations communities [2,3].

Land in the south not covered by lakes was historically considered “wet prairie”, a unique tall-grass prairie. Now, much of the southern region is characterized by drainage ditches, levees, and culverts used to convert the wet prairie to agriculture [1,49]. In its totality and for each individual case, drainage and dams have been a contentious project and continue to have social, ecological, and hydrological impacts on communities across the province.

Over the last 25 years, Manitoba has implemented numerous water policies, originally focusing on water quality, conservation, use and allocation, water supply, flooding, drainage, and education, but without explicitly addressing First Nations and Métis rights [50]. In 2003, the Manitoba Water Strategy [51] established an integrated approach to implementing the 2000 strategy. This involved updating water legislation, funding planning and implementation, and recognizing the existence of Aboriginal and Treaty rights. The 2003 strategy introduced the idea of reconciliation in water management, characterizing Indigenous–state relations in terms of “mutual recognition, respect, resource sharing and responsibility” [51] (p. 7). While constitutionally protected rights are to be “defined and respected”, specifically in the context of water use and allocation (p. 13), the strategy does not explain how or when it will happen. First Nations engagement could occur via additional targeted public engagement-style consultations or by individual and group interviews—an “accommodation” from the government for remote reserve communities and individuals who cannot travel to attend meetings. These engagements were conducted by individuals, organizations, or committees that were not legally empowered to recognize, define, or accommodate Aboriginal and treaty rights [52,53]. Water use and allocation decisions—those subject to Aboriginal and Treaty rights—would be addressed outside of the planning process.

In 2014, the Surface Water Management Strategy [54] was released, describing “three pillars of action” for sustainable water management: water quality, extreme events, and “co-ordination and awareness” (p. 6). This strategy seeks to decentralize decision-making and integrate “local priorities, issues, and solutions [into plans] within a municipal and provincial perspective” (p. 21). It also proposes capacity building and improving or enhancing participation and again calls for the recognition of and respect for Aboriginal and Treaty rights. The strategy does not explain how recognition of those rights or responsibilities will be implemented. For example, the strategy recognizes the significance of wetland ecosystems to “First Nations and Métis traditional ways of life” (p. 11) and establishes wetland protection as a policy goal but does not articulate how First Nations or Métis people are to be involved in establishing measures and criteria of success in wetland protection relative to the recognition and protection of their rights.

Pillar 3 of the strategy states that planners and decision-makers must “Ensure that shared governance approaches are inclusive of all watershed stakeholders, including Métis communities and First Nations” (p. 24), reiterating the “official” position toward their relationship with Indigenous peoples as stakeholders in integrated water management, not as nations in co-governance. The strategy is in some ways contradictory, seeking better relationships with Indigenous peoples, but still choosing to constrain engagement to management-level discussions: First Nations are again listed alongside other stakeholder groups, not as Nations.

More recent changes to water policy and legislation in Manitoba came in early 2020 [55], with a new water management strategy in 2022 [56]. Alongside administrative changes (conservation districts renamed as watershed districts, and adjustments made to their boundaries), the districts were also empowered to enter into partnerships “with non-municipal entities, including Indigenous nations” [57]. Watershed planning authorities (WPAs) must also consult with “any band, as defined in the Indian Act (Canada), that has reserve land within the watershed” [55]. While enabling partnerships and requiring consultation are positive steps towards greater Indigenous inclusion during planning and implementation, they do not resolve the exclusion of Indigenous peoples during the development of provincial water policy and legislation, both of which are integral to collaborative water governance [28]. These provisions also fall short of recognition of Aboriginal and Treaty rights, as the consultations are not rights-based—that is, they are not intended to fulfill government’s Duty to Consult in response to potential impacts on constitutionally protected rights.

The latest strategy again includes a goal to “advance Indigenous inclusion in water management” [56] (p. 30). The strategic objectives associated with this goal center on including Indigenous knowledge in water management, clarifying “the respective [water management] roles” of government and Indigenous communities, and support the inclusion of Indigenous communities in water management activities undertaken by local governments, authorities, and organizations. As no plans have been completed under this policy, we do not examine it further.

We note that Manitoba’s watershed plans are non-statutory. During the preparation or amendment of zoning bylaws or municipal development plans, decision-makers at local and regional levels must consider—but not abide by—the policies and objectives of “an approved watershed plan” [58] (p. 14). The implementation of plans relies on voluntary actions of individuals, landowners, and other entities. Although these plans are not enforceable, they do provide insight into the local issues and contexts in which Indigenous engagement does or does not occur.

With respect to water management and impacts on Aboriginal and Treaty Rights, it is important to note that many impactful decisions are made outside of watershed planning. Hydroelectric projects in Manitoba are planned and managed by Manitoba Hydro, a Crown corporation, and effects from these projects are outside the domain of watershed planning [59]. Conversely, watershed plans do not significantly influence the planning of Manitoba Hydro’s projects.

Climate change adaptation and planning also influences water management in Manitoba. Published in 2017, their strategy begins with an acknowledgement of the significance of Indigenous and local knowledge in guiding adaptations to climate change. Water is identified as a pillar of action within the strategy, with key actions including the promotion of beneficial management practices in agriculture, water storage (no net loss wetland drainage) to protect against flood and drought, the management of excess nutrients, protection of aquifers and shorelines, and the enforcement of regulations [60].

1.3. First Nations in Manitoba

According to Indigenous Services Canada [61], there are 63 First Nation bands in Manitoba with approximately 163,000 registered members across five different linguistic groups. The population of First Nation members between the northern and southern regions is not precisely known, but estimates based on representation in the primary tribal organizations suggest that there are slightly more First Nation people in the south than the north [62]. Not all First Nation people are members of reserves. With treaties, lands were set aside for First Nation people. Approximately half of the registered members live on-reserve, though this does not mean that members living off-reserve do not participate in the cultural practices or social activities of their communities. A map of reserve land is shown in Figure 3.

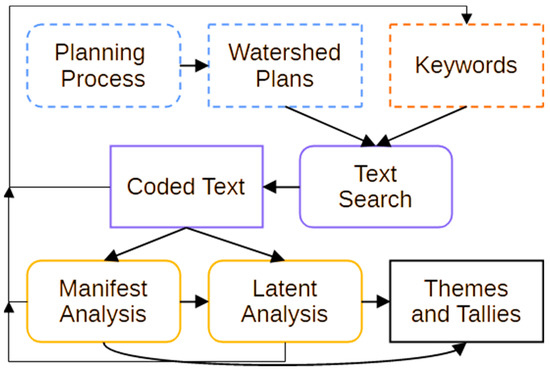

Figure 3.

Diagram of analytical inputs, process, and outputs, with arrows indicating the sequence and flow of information.

Due to colonialism, isolation, and systemic racism, First Nation people in Canada typically experience poorer socio-economic conditions than non-Indigenous Canadians [63]. According to the 2016 census, First Nations people in Manitoba did not complete high school at 3.7 times the rate of non-Indigenous people [64]. These statistics do not, however, reflect the knowledge, understanding, and wisdom of Indigenous knowledge as it relates to water management. They do, however, suggest that education is a barrier to engaging in water management processes and water governance regimes that privilege or are exclusive to “Western” scientific knowledge.

Textual documentation of public and Indigenous engagements in watershed planning is recognizable by the use of keywords, concepts, and content related to Indigenous Peoples. This evidence is considered here as both an output and outcome of Indigenous participation in watershed planning and water governance. We explain our methods in more detail next.

2. Methods and Data

This study uses content analysis of watershed plans to describe Indigenous engagement in Manitoba’s water governance and watershed planning processes. Examining the documents that structure and serve as a record of engagements between Indigenous peoples and the state, such as policies, legislation, and resource management plans, can give insight into the opportunities, barriers, and contexts of engagement [65,66]. We consider watershed planning as a subset of water governance institutions, practices, and processes. As outputs of the planning process, watershed plans are our objects of content analysis. We identify and count how often Indigenous-related keywords occur in Manitoba’s watershed plans, and then we thematically code the keywords according to their apparent and contextual use in the document. A diagram representing the process is shown in Figure 3.

2.1. Content Analysis

Content analysis is “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns” [67] (p. 1278). The purpose of a content analysis is to “draw inferences about related patterns in the contexts in which those texts are produced or used” [68] (p. 28). A similar approach has been used to study water governance in Saskatchewan and Alberta [19,20] and climate change in British Columbia [69]. Our content analysis has two components: a summative approach explored the manifest use of words and phrases, and an interpretative approach explored the latent meaning in the use of the keywords [67]. Taking into consideration the context in which the words are used adds a qualitative dimension that “strengthen[s] the validity of the inferences that are being made from the data” [70].

We argue that resource management plans can tell a story of Indigenous (dis)engagement [71,72]. These plans are produced within specific legislative frameworks, are developed, informed, and influenced by people—members of the public, organizational representatives, or government employees—who participate or are otherwise involved in the planning process, and apply a generic framework to a particular time and place [73,74]. In short, if the practice of watershed planning is the translation of water policy into water management, then we can look to plan documents for evidence of Indigenous engagement in provincial water governance.

The lead author conducted keyword searches of the plans to identify content related to Indigenous engagement in the watershed planning process. Initial keywords included the following list, and more specific identifiers were included as they appeared in the plans (e.g., specific names of First Nations):

“first nation?” OR “indig*” OR “aborig*” OR “m?tis” OR “cree” OR “dene” OR “dakota” OR “nation” OR “indian”

The keywords were coded according to their use and surrounding text according to its context [75,76]. For example, the code of “Implementation” applies to text referencing a management action, or the code “Recognition” if keywords appeared in the context of Aboriginal or Treaty rights. An initial set of codes was established from a subset of watershed plans with an Indigenous content [77]. Coding and sorting were iteratively revised and refined [67] until the text was coded into categories that were “mutually exclusive and exhaustive” [70]. We identified five themes with varying numbers of subthemes.

The lead author was the sole coder, an approach that can be criticized for potentially compromising the reliability of the analysis [70,75]. However, the validation of findings was supported through triangulation [70], achieved by conducting semi-structured interviews with government watershed planners that wrote or were involved in producing some of the watershed plans included in the study.

2.2. Data

The dataset included 22 watershed management plans, including draft and final plans but excluding supplementary documentation such as background studies, memorandums of understanding, terms of reference, and stakeholder feedback summaries. Background studies and stakeholder feedback are typically integrated into the plans as their factual basis, or sometimes as appendices. It is important to note that summary reports only address public stakeholder engagements and not consultations with First Nations communities. The watershed plans bring all this information together, and for that reason they are the focus of the analysis. Documentation from watershed planning can be found by clicking on the respective watershed on the Government of Manitoba’s website, https://www.gov.mb.ca/sd/water/watershed/iwmp/index.html (accessed on 2 February 2024). The documents are typically linked in the Planning Documents tab within those pages.

Watershed plans were completed between 2006 and 2018. Figure 2 shows a map of Manitoba, including polygons for water, land designations, and watershed boundaries, differentiated by the year in which the watershed plans were completed. Some plans were developed under Manitoba’s 2003 water strategy, and the rest were completed after publication of the 2014 surface water strategy. Given that the 2014 strategy emphasized building capacity for engagement, we might expect more evidence of engagement in the later plans. We explore this possibility below.

3. Results and Analysis

Using the keyword and thematic counts, we calculated the relative proportion of thematic coding in each plan, the relative proportion that each plan accounts for in the overall coding in each theme, and tallied the number of themes in each plan as a measure of thematic diversity (TD). We also describe how coding varies over time by dividing the plans into two periods (see below). The term “keyword occurrence” (KO) refers to the presence of a keyword. Next, we describe the themes and then their distribution.

3.1. Theme Descriptions

We identified five themes, along with subthemes, and organized the thematic results into two temporal groups (periods) according to the year of plan publication (pre- or post-2013), which roughly aligns with finalization of the 2014 water strategy. The first period spans four years, and the second spans five; each period has 11 plans. Table 1 shows the annual thematic and total distributions of KOs, TD, and the number of plans with and without codes by year. Table 1 also subtotals KOs for each theme by period, showing the temporal distribution of coding within themes.

Table 1.

Frequency of keyword occurrences in each theme by year.

3.1.1. Participation

Coding for Participation typically relates to engagement mechanisms such as general public meetings and invitations to participate in the process or on committees. Other examples of participation coding include acknowledgments of Indigenous participants and their contributions, the mention of participating agencies with an Indigenous mandate, and the mention of Indigenous participation in other resource management committees or processes. Coding for participation does not mean that a First Nation participated in the process. Notably, in only two occurrences were “public meetings” discussed explicitly in relation to Indigenous peoples, and only one plan indicated that public meetings were held on reserve or in an Indigenous community (Fisher). Indigenous peoples are infrequently noted as participating on the project management team, and sometimes on the watershed team (effectively as a stakeholder).

As shown in Table 1, Participation codes are the most widespread but not the most frequent, appearing 64 times across 16 plans and accounting for 20.9% of total thematic KOs. Distribution across the two periods is the same but relatively uneven across plans given that there are 32 KOs across 6 plans in P1, and 32 across 11 plans in P2.

3.1.2. Land

The theme of Land refers to the use of Indigenous keywords in describing some aspect of geographic space. Land-related codes are most often and extensively applied to map labels (12 plans, 33 KOs), they less often and extensively describe the relative location of various geographic features (7 plans, 12 KOs), and they occasionally refer to reserve land and TLE parcels (4 plans, 5 KOs) or activities on Crown land that may trigger rights-based consultation (3 plans, 4 KOs).

It is the second most extensive theme, appearing 54 times across 12 plans and accounting for 17.6% of KOs, and coding in P2 is more than four times that in P1 (Table 1).

3.1.3. Representation

Content coded as Representation is either a direct quotation attributed to an Indigenous participant, or indirect, as part of a summary or synthesis of interviews and Indigenous input through public engagement. This content typically includes representations of Indigenous knowledge, values, and interests. Most codes were grouped into one of three major subthemes: environmental change and impacts; responsibilities and relationships; and interests and values.

Representation-themed content was most frequent, found 87 times across 10 plans, accounting for 28.4% of KOs, and it was nearly forty times as frequent in P2 than P1 (Table 1). Given the relevance of this theme to engagement and the descriptions of changes to watersheds observed by Indigenous peoples, we describe some of the subthemes in more detail below.

Environmental Change and Impacts

Codes for environmental change and impacts were most wide-spread and frequent for the Representation theme (7 plans, 15 KOs), highlighting issues such as “more frequent flooding” and “increased surface water flows” (Cook’s—Devil’s), rising lake levels (Westlake), and changes in stream flow volume and timing (Swan Lake). Some of the causes identified are the following: channelization and drainage infrastructure for agriculture (Pembina), breaks in beaver dams (Southwest Interlake), low-lying geography (Fisher River), or hydroelectric infrastructure and management (Carrot—Saskatchewan). Observations of erosion from denuded creeks and ditching in agricultural fields, with subsequent sedimentation downstream, are noted as negatively impacting the extent and quality of aquatic and riparian habitats (Swan Lake, Cook’s—Devil’s, Carrot—Saskatchewan). Agricultural drainage, forestry, and peat harvesting activities are specifically identified as impacting riparian areas and fish habitats. The loss and alteration of habitats was described as affecting not only animals (5 plans, 11 KOs) but also plants, medicines, water, and ice quality as well (4 plans, 7 KOs). Indigenous observers noted changes in animal population and behavior because of these changes (4 plans, 8 KOs), including dispersal (Swan Lake), changes in migration patterns and population—especially for moose (Westlake, Swan Lake, Dauphin Lake, and Fisher River)—and changes in fish species and abundance (Westlake).

Indigenous Relations and Responsibilities

Text that discussed Indigenous relationships and responsibilities were almost as extensive and frequent as those for environmental change. References included place-based relations (7 plans, 16 KOs) including stewardship (Netley—Grassmere, Fisher, Central Assiniboine, Cook’s Creek—Devil’s Creek), and familial and tribal connections to specific areas (Westlake, Central Assiniboine, Swan Lake, Carrot—Saskatchewan). There were also several general statements about traditional and contemporary use (5 plans, 7 KOs), most often in relation to conservation-focused plan objectives meant to support traditional use activities. Indigenous relationships with and responsibilities for water (4 plans, 6 KOs) acknowledge water “as the source of life for all living things… [water is] alive and is a spirit” (Swan Lake, similar in Cook’s—Devil’s Creek, Carrot—Saskatchewan) and that “women are responsible for caring for the water” (Fisher River). All mentions of water in the context of Indigenous peoples refer to the significant role water has in the ecosystem and human health.

Indigenous Interests and Values

Representations of Indigenous interests and values emphasized fishing, wildlife, and medicines. Fishing interests and values (6 plans, 12 KOs) discuss the significance of fish species—such as sturgeon—to First Nations communities (Central Assiniboine, Swan Lake, Fisher, Cook’s, Carrot—Saskatchewan, Dauphin Lake); three plans mention Indigenous commercial fishing interests. Wildlife interests and values were the second-most frequent and extensive (5 plans, 12 KOs), with observations on loss of wildlife habitat, declining moose population and health (Carrot—Saskatchewan, Dauphin Lake, Swan Lake), concerns about human impacts on wildlife generally, and comments about the important relationship between land, water, and wildlife. Only the Fisher River plan mentions Aboriginal and Treaty rights in relation to wildlife. Access to traditional medicines was interwoven with other concerns around traditional land use, food harvesting, wildlife, and ecology. Other references include general statements of community concerns, descriptions of community drinking water systems, statements of traditional knowledge, and mentions of Indigenous non-government organizations.

3.1.4. Recognition

Recognition coded text discusses the inclusion of Indigenous peoples and communities in water and resource management processes and institutions, self-determination, and First Nation–Crown treaties. Recognition-coded content appears 46 times across 10 plans, accounts for 15% of KOs, and is 22 times more frequent in P2 than P1 (Table 1). Given the relevance of this content to Aboriginal and Treaty rights, we again describe some of the subthemes in more detail.

Integration

Integration is the most frequent and extensive sub-theme under recognition (9 plans, 33 times), discussed in terms of consultation (peat harvesting in Fisher River and Cook’s—Devil’s Creek; hydroelectric water management in Carrot—Saskatchewan) and Aboriginal and Treaty rights in relation to traditional land use and harvesting in parks (Dauphin Lake, Fisher River, and Carrot—Saskatchewan). Reference to Indigenous knowledge typically appears as an objective or goal to “incorporate traditional knowledge into development plans” (Swan Lake, Cook’s Creek—Devil’s Creek, and Carrot—Saskatchewan). Additionally, a few plans mentioned agreements, partnerships, shared jurisdiction, funding, and the inclusion in planning of government agencies with a mandate to administer Indigenous programs, administration, or funding.

Self-Determination

Reference to traditional territory comprises the bulk of coding for self-determination. Text about treaty territories could be coded as location (Land theme) or relationships to place (Representation theme), but text is coded as self-determination when the context is Indigenous decision-making within historic and contemporary land bases. Self-determination also includes mentions of First Nation authority in development planning and band administration; there is no mention of consent in any of the plans. Treaty relationships are mentioned explicitly twice (Cook’s—Devil’s and Carrot—Saskatchewan) and indirectly in reference to treaty land entitlements (Cook’s—Devil’s).

3.1.5. Implementation

The theme of Implementation relates to the inclusion of Indigenous peoples and communities in management actions. Implementation-themed content occurs 55 times across 8 plans, accounting for 18% of all KOs (Table 1). Distribution between periods is again much higher in P2 than P1, by a factor of more than 26. The Dauphin Lake plan is an outlier with the most occurrences (14) of all plans, and where implementation has the highest proportion of codes relative to other themes (56%, see Supplementary Materials).

The bulk of implementation coding focuses on management actions and objectives, or recommendations, measures of success, and identifying whether Indigenous communities have supporting, lead, or co-lead responsibilities. Source water protection for Indigenous communities is also mentioned in terms of wastewater (Central Assiniboine); groundwater extraction, pollution, and aquifer recharge (Central Assiniboine and Fisher); source water protection zones (Carrot—Saskatchewan); and the sealing of abandoned wells (Fisher and Carrot—Saskatchewan).

3.2. Theme Distribution

First, we show how theme proportions and diversity change over time, and second, we describe how thematic proportions change with increasing diversity.

3.2.1. Temporal

The distribution of thematic coding between periods (Table 1) shows that except for Participation, P2 generally has much higher KO counts. Not only are there more plans with KOs in P2, but there are also more KOs per plan than in P1. Thematic coding is more evenly distributed across the themes in P2, and P2 has a greater average thematic diversity (4.0 vs 1.1).

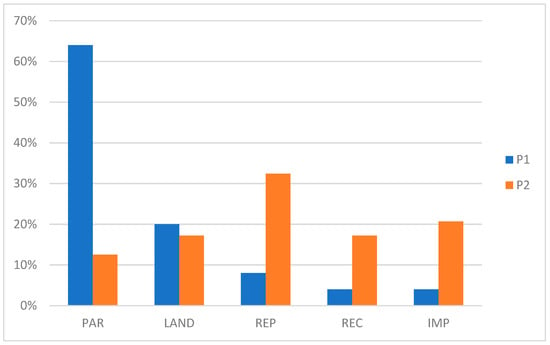

The proportional distribution of KOs between themes and periods is shown in Figure 4 and Table 1. Within P1, Participation is most frequently coded by a wide margin (64% of period coding), followed by Land (20%); Representation, Recognition, and Implementation accounted for the rest. Within P2, the variance is less uneven: Representation is most frequently coded (32% of period coding), followed by Implementation (21%), Land (17%), Recognition (17%), and Participation (13%).

Figure 4.

Percentage distribution of keyword occurrences across themes by time period.

Six plans in Period 1 have Indigenous keyword occurrences: two plans from 2010 and four from 2011. Those six plans have 50 KOs between them, which is approximately 16% of total KOs across all plans. As shown in Table 1, all plans in Period 2 have KOs, accounting for approximately 83% of the total; two years in P2 are particularly significant: 2014 (24%), and 2015 (51%). Figure 3 and Table 1 show that there is greater variation in KOs for P2 than P1. In short, more plans in P2 had KOs, and those plans had most of the total KOs. A list of the plans and details such as the year of publication and KO tallies can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Plans published in P2 have more evidence of Indigenous inclusion and more themes coded on average. In particular, the change in the dominant theme from Participation in P1 to Representation in P2 suggests that Indigenous engagement in the planning process moved from mostly invitations to a point where Indigenous voices and interests were being heard at meetings or through interviews and subsequently incorporated into watershed plans. We also see Indigenous peoples more often identified as partners or participants in Implementation activities in P2. While we may try to explain this change as a result of the 2014 strategy, there are other influential factors that are not addressed by the content analysis.

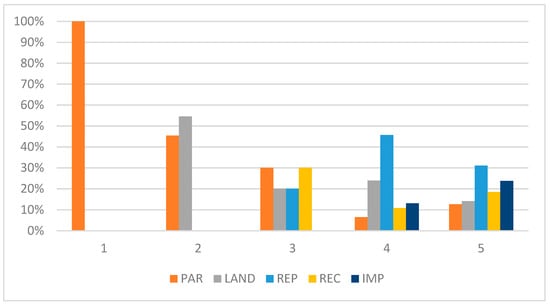

3.2.2. Diversity

We can also look at how much each theme contributes to theme diversity. As shown in Table 2, most Participation KOs are either in plans with all five themes, or where Participation is the only theme. Land KOs appear the most in plans with all five themes and in plans with two or four themes. Representation KOs are only apparent in plans that have three or more themes but essentially only in those with four but usually five themes. Recognition KOs appear in plans with three or more themes, but again most of these are in plans with four or usually five themes. Finally, Implementation KOs appear only in plans with four or five themes, and then most often in plans with five themes.

Table 2.

Proportion of thematic coding by thematic diversity.

When we consider the relationship between KOs and thematic diversity, we can see in Figure 5 that the relative proportion of Participation coding generally decreases with increasing thematic diversity, with codes shifting towards Land (TD = 2), then Representation and Recognition (TD = 3), and for higher levels of thematic diversity (4+), Representation becomes dominant.

Figure 5.

Distribution of thematic codes across levels of diversity.

4. Discussion

This study sought to characterize Indigenous engagement in watershed planning in Manitoba. Over time, Indigenous-related content in Manitoba’s watershed plans has increased in frequency, extent, and diversity. As the diversity of Indigenous content increases, themes related to representation become most common. Later plans show greater attention to the knowledge and experiences of Indigenous peoples, and Indigenous peoples also have more often been included as actors or partners in implementation. However, we did not find an increase in the mention or detailing of Aboriginal and Treaty rights in the context of water management.

4.1. Structural Recognition

Treaty relations are foundational for First Nation–Crown (government) relations. The repeatedly stated policy intended to define and respect Aboriginal water rights for allocation and use through planning [51,54] did not lead to the articulation of water rights in watershed plans. Treaty-related content in plans is brief and does not address Indigenous water rights within their traditional territories. Recent government policy acknowledges Indigenous peoples’ interests in the wetland ecosystem, yet Indigenous observations of environmental change documented in plans show that community interests and values related to wetlands do not trigger a rights-based response by government. In fact, allocation and use are not the primary Indigenous concerns represented in the plans.

Water quality, environmental water, and impacts on water from land cover and land use change impact Aboriginal and Treaty rights, but regulations for these impacts are beyond the reach of the “integrated” watershed planning process—whether these rights are based on use and allocation or incidental to other already recognized rights [78,79]. In addition, most drainage projects and licenses are approved by the province through a separate regulatory process, and provincial fisheries management occurs through a branch of government that does not have jurisdiction to regulate upstream land use, even if it degrades fish habitat (Manitoba regional fisheries manager, 2019). Watershed planning institutions lack the appropriate mandate to recognize Indigenous water rights, let alone the means of defining and upholding Indigenous rights in relationship to wetland or ecosystem values.

Even if water-related rights were to be determined through planning and articulated in watershed plans, water planning authorities are still not empowered to consult, and where appropriate, accommodate Indigenous peoples in accordance with their constitutionally protected rights [52,53]. Even though legislative changes in 2020 allow for partnerships between watershed (conservation) districts and First Nations, districts have no authority to regulate land use changes that may impact Indigenous rights. Instead, achieving plan objectives requires voluntary uptake, especially when involving private land.

For example, agricultural drainage—leading to declines in water quality, wetland loss, species abundance, and species diversity—may impact Aboriginal rights to fish, hunt, and gather. Illegal drainage has long been an issue that the province has struggled to address [80]. The province is responsible for regulating drainage; while some watershed/conservation districts are involved in the licensing of drainage activities, they are not empowered to consult or even required to inform potentially affected First Nations of drainage licensing applications. Community members of Wuskwi Sipihk First Nation identified extensive illegal drainage as the cause of impacts locally to the First Nation and across the province. Yet, plans included no discussion of how the district, provincial or local governments, or local landowners would address such impacts in relation to Aboriginal and Treaty rights.

4.2. Participation and Processes

As in Alberta and Saskatchewan, First Nations are considered by the province to be stakeholders, and the government considers the planning process to be a function that does not impact Aboriginal and Treaty rights and therefore does not trigger the duty to consult. This position is consistent with other prairie provinces with historic treaties [19,20]. Community consultation, as an extension of public consultation within the existing water management framework, reproduces the stakeholder relationship model and continues to exclude Indigenous peoples from nation-to-nation water governance [28,48]. Such a framing of Indigenous peoples as stakeholders is a critical divergence from the best practices of Indigenous engagement in water governance identified in the literature [48,81]. Instead of best practices, Indigenous peoples are repeatedly treated as stakeholders, and their interests and values are weighted equally with those of other stakeholders.

While there are examples of cooperation in implementation between First Nations and conservation districts, there has been little to no representation of Indigenous peoples on conservation district boards [82] and limited consultation with First Nations on the development of water policy and legislation. In fact, requests from Wuskwi Sipihk First Nation to be consulted by the government over the most recent changes to water policy and legislation were met by delays and deferrals (Wuskwi Sipihk Treaty Land Entitlement manager, 2023, personal communication).

The goals stated in the 2014 Surface Water Strategy were to increase inclusion, build capacity, and recognize Aboriginal rights in the context of water use and allocation [54]. We found evidence of an increase in inclusion but did not find evidence of specific programs or funds aimed at building Indigenous capacity to participate in planning or water management. We also found sparse discussions of Aboriginal and Treaty rights in any context, let alone water use and allocation. While community self-selection or self-exclusion from resource planning may account for some of the absence or weakness in the recognition of Aboriginal and Treaty rights, interviews with watershed planners reinforced that this was a systemic issue—watershed planners recognize that Aboriginal and Treaty rights exist, but they are to be defined and accommodated in other processes—through fisheries management, wildlife management, and through hydroelectric water use licensing. While Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the context of forestry, parks, and protected area management planning are mentioned in some watershed plans—and these may have incidental water rights attached [79]—these rights were not substantively related to management actions or recommendations. We find that overall, implementation is inconsistent, uneven, and Aboriginal and Treaty rights are still largely unrecognized.

5. Conclusions

The presence of Aboriginal reserve land in a watershed is identified in the legislation as a trigger for consultation with First Nations communities. Aboriginal inclusion has been a key policy directive in Manitoba’s water strategy for the last 20 years. Yet, Aboriginal and Treaty rights are not discussed in any significant degree in most of the watershed plans we examined. The overall increase in the amount of Indigenous engagement between time periods may be a result of the Government of Manitoba’s emphasis on Indigenous inclusion and capacity building in its 2014 surface water strategy, but we cannot draw a conclusion on this without additional evidence of programming and funding to build capacity.

In summary, even though drainage, land use change, and resource extraction likely impact Aboriginal and Treaty rights to fish and hunt, these activities are regulated externally to Manitoba’s “integrated” watershed planning process. The non-regulatory nature of watershed plans means that watershed planning itself does not trigger a legal Duty to Consult and, where appropriate, accommodate. We view this as a failure in the current water governance approach in Manitoba. The integration of watershed planning and management appears incomplete and incapable of sufficiently addressing First Nations’ concerns, interests, and rights. Any efforts to address Indigenous rights and interests are not explicitly recognized, and they are limited to recommended or voluntary actions or are considered incidentally as part of broader conservation goals. Indigenous participation in watershed planning may influence some watershed objectives or actions, but arguably, Indigenous peoples should seek alternative arenas to further their rights-based claims.

Adapting water management to future climate change will involve significant changes to water management practices and infrastructure. While the protection of human health and life is a shared goal, Indigenous peoples must be consulted to determine the numerous relations to land, water, and more-than-human life that comprise and give meaning to their cultural milieu. The specific impacts they do and will continue to experience are mediated by their webs of relationality, their social determinants of health, and their geographies. Effective (and inclusive) water governance in Manitoba must be responsive to the distinct needs, interests, and rights of Indigenous peoples.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w16121734/s1, Table S1: Frequency of thematic keyword occurrences and content variables by plan.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.B., R.J.P. and C.F.; methodology, W.B., R.J.P. and C.F.; formal analysis, W.B.; investigation, W.B.; data curation, W.B.; writing—original draft preparation, W.B.; writing—review and editing, R.J.P. and C.F.; visualization, W.B.; supervision, R.J.P. and C.F.; funding acquisition, C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada CREATE-432009-2013 grant. The APC was funded by the University of Saskatchewan.

Data Availability Statement

Watershed plans used in this study are publicly available from the Government of Manitoba, Canada, as linked in the article. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bower, S.S. Wet Prairie: People, Land, and Water in Agricultural Manitoba; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, F. As Long As the Rivers Run: The Impacts of Corporate Water Development on Native Communities in Canada. Can. J. Nativ. Stud. 1991, 11, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Waldram, J.B. As Long as the Rivers Run: Hydroelectric Development and Native Communities in Western Canada; University of Manitoba Press: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1988; ISBN 978-0-88755-143-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, K.; Simms, R.; Joe, N.; Harris, L. Indigenous Peoples and Water Governance in Canada: Regulatory Injustice and Prospects for Reform. In Water Justice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, M. Where the Waters Divide: First Nations, Tainted Water and Environmental Justice in Canada. Local Environ. 2007, 12, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, D. Mino-Mnaamodzawin: Achieving Indigenous Environmental Justice in Canada. Environ. Soc. Adv. Res. 2018, 9, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, J.; Cosens, B.; Jackson, S.; Leonard, K.; McCool, D. Indigenous Water Justice. Lewis Clark L. Rev. 2018, 22, 841–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, K.; Cook, C. Water Governance in Canada: Innovation and Fragmentation. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2011, 27, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, E. Water Sovereignty for Indigenous Peoples: Pathways to Pluralist, Legitimate and Sustainable Water Laws in Settler Colonial States. PLoS Water 2023, 2, e0000144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Loë, R.C. Toward a Canadian National Water Strategy; Canadian Water Resources Association: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Craft, A. Anishinaabe Nibi Inaakonigewin Report; University of Manitoba Centre for Human Rights Research and Public Interest Law Centre: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Craft, A.; McGregor, D.; Seymour-Hourie, R.; Chiblow, S. Decolonizing Anishinaabe Nibi Inaakonigewin and Gikendaasowin Research: Reinscribing Anishinaabe Approaches to Law and Knowledge. In Decolonizing Law: Indigenous, Third World and Settler Perspectives; Indigenous Peoples and the Law Series; Xavier, S., Jacobs, B., Waboose, V., Hewitt, J.G., Bhatia, A., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 17–33. ISBN 978-1-00-316138-7. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, D. Traditional Knowledge and Water Governance: The Ethic of Responsibility. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2014, 10, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phare, M.-A.S. Aboriginal Water Rights Primer; PHARE LAW: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lautze, J.; de Silva, S.; Giordano, M.; Sanford, L. Putting the Cart before the Horse: Water Governance and IWRM. In Natural Resources Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2011; Volume 35, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; McGregor, D.; Allen, S.; Murray, C.; Metcalfe, C. Source Water Protection Planning for Ontario First Nations Communities: Case Studies Identifying Challenges and Outcomes. Water 2017, 9, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, D. Anishnaabe-Kwe, Traditional Knowledge and Water Protection. Can. Woman Stud. 2008, 26, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, D. Traditional Knowledge: Considerations for Protecting Water in Ontario. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2012, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.; Baijius, W.; Patrick, R.J. Water for Life in Alberta, Canada: Assessing First Nations Engagement. Can. Plan. Policy/Aménagement Et Polit. Au Can. 2023, 2023, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baijius, W.; Patrick, R.J. Planning Around Reserves: Probing the Inclusion of First Nations in Saskatchewan’s Watershed Planning Framework. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2019, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, F.; Viswanathan, L.; Whitelaw, G.S.; Macbeth, J.; King, C.; McCarthy, D.D.; Alexiuk, E. Finding Common Ground: A Critical Review of Land Use and Resource Management Policies in Ontario, Canada and Their Intersection with First Nations. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2015, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, H.; Hildebrandt, W. Treaty Elders of Saskatchewan: Our Dream Is That Our Peoples Will One Day Be Clearly Recognized as Nations; University of Calgary Press: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Krasowski, S. No Surrender: The Land Remains Indigenous; University of Regina Press: Regina, SK, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D. Revisiting the Duty to Consult Aboriginal Peoples; Purich Publishing Limited: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N.J. “Seeing Water Like a State?”: Indigenous Water Governance through Yukon First Nation Self-Government Agreements. Geoforum 2019, 104, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.J. Querying Water Co-Governance: Yukon First Nations and Water Governance in the Context of Modern Land Claim Agreements. Water Altern. 2020, 13, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N.J.; Harris, L.; Joseph-Rear, A.; Beaumont, J.; Satterfield, T. Water Is Medicine: Reimagining Water Security through Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Relationships to Treated and Traditional Water Sources in Yukon, Canada. Water 2019, 11, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P. The Blue Paper: Water Co-Governance in Canada; Forum for Leadership on Water: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, K.; Newman, D. The End Is Not Nigh: Reason over Alarmism in Analysing the Tsilhqot’in Decision; Macdonald-Laurier Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Slattery, B. Making Sense of Aboriginal and Treaty Rights. Can. Bar Rev. 2000, 79, 196–224. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, D. Indigenous Processes of Consent: Repoliticizing Water Governance through Legal Pluralism. Water 2019, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.J.; Inkster, J. Respecting Water: Indigenous Water Governance, Ontologies, and the Politics of Kinship on the Ground. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2018, 1, 516–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, P. Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native. J. Genocide Res. 2006, 8, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baijius, W.; Patrick, R.J. “We Don’t Drink the Water Here”: The Reproduction of Undrinkable Water for First Nations in Canada. Water 2019, 11, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basdeo, M.; Bharadwaj, L. Beyond Physical: Social Dimensions of the Water Crisis on Canada’s First Nations and Considerations for Governance. Indig. Policy J. 2013, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, L.E.A.; Ovsenek, N.; Bharadwaj, L.A. Indigenizing Water Governance in Canada. In Water Policy and Governance in Canada; Renzetti, S., Dupont, D.P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 17, pp. 269–298. ISBN 978-3-319-42806-2. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, R.J. Uneven Access to Safe Drinking Water for First Nations in Canada: Connecting Health and Place through Source Water Protection. Health Place 2011, 17, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNGA United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/471355a82.html (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Bland, D. Canada and the First Nations: Cooperation or Conflict? Macdonald-Laurier Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, K.S.; Favel, B. Understanding FPIC: From Assertion and Assumption on ‘Free, Prior and Informed Consent’ to a New Model for Indigenous Engagement on Resource Development; Macdonald-Laurier Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Favel, B.; Coates, K.S. Understanding UNDRIP: Choosing Action on Priorities over Sweeping Claims about the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; Macdonald-Laurier Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shrubsole, D.; Walters, D.; Veale, B.; Mitchell, B. Integrated Water Resources Management in Canada: The Experience of Watershed Agencies. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2017, 33, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Porten, S.; de Loë, R.C. How Collaborative Approaches to Environmental Problem Solving View Indigenous Peoples: A Systematic Review. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 1040–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasiewicz, A.; Baldwin, C. Voice, Power, and History: Ensuring Social Justice for All Stakeholders in Water Decision-Making. Local Environ. 2014, 22, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.; Xu, W.; Bjornlund, H.; Edwards, J. A Table for Five: Stakeholder Perceptions of Water Governance in Alberta. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 174, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.-L.; von der Porten, S.; Castleden, H.E. Consultation Is Not Consent: Hydraulic Fracturing and Water Governance on Indigenous Lands in Canada. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.-Water 2017, 4, e1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phare, M.-A.S. Restoring the Lifeblood: Water, First Nations and Opportunities for Change; Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- von der Porten, S.; de Loë, R.C.; Plummer, R. Collaborative Environmental Governance and Indigenous Peoples: Recommendations for Practice. Environ. Pract. 2015, 17, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, S.S. Watersheds: Conceptualizing Manitoba’s Drained Landscape, 1895–1950. Environ. Hist. 2007, 12, 796–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manitoba Sustainable Development. Applying Manitoba’s Water Policies; Government of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2000.

- Government of Manitoba. The Manitoba Water Strategy; Government of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2003.

- Promislow, J. Irreconcilable?: The Duty to Consult and Administrative Decision Makers. Can. J. Adm. Law Pract. 2013, 26, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sossin, L. The Duty to Consult and Accommodate: Procedural Justice As Aboriginal Rights. Can. J. Adm. Law Pract. 2010, 23, 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Manitoba. Manitoba Surface Water Management Strategy; Government of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2014.

- Government of Manitoba. The Water Protection Act, C.C.S.M. c. W65; Government of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba Environment and Climate. Change Manitoba’s Water Management Strategy; Government of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2022; p. 48.

- Manitoba Association of Watersheds Manitoba’s Conservation Districts Renamed Watershed Districts with New Tools to Protect Our Watersheds. Available online: https://manitobawatersheds.org/news/manitobas-conservation-districts-renamed-watershed-districts (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Unger, J. Consistency and Accountability in Implementing Watershed Plans in Alberta: A Jurisdictional Review and Recommendations for Reform; Environmental Law Centre: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Manitoba. The Water Rights Act C.C.S.M. c. W80; Government of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development Manitoba. A Made-in-Manitoba Climate and Green Plan: Hearing from Manitobans; Government of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2017; p. 64.

- Government of Canada. Indigenous Services Canada; First Nations in Manitoba. Available online: https://sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1100100020400/1616072911150 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Southern Chiefs Organization Inc. First Nations Leaders Resolve to Protect Land in Manitoba. Available online: https://scoinc.mb.ca/first-nations-leaders-resolve-to-protect-land-in-manitoba/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Jardine, C.; Lines, L.-A. Social and Structural Determinants of Indigenous Health. In Northern and Indigenous Health and Healthcare; Exner-Pirot, H., Norbye, B., Butler, L., Eds.; University of Saskatchewan: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada; Pan-Canadian Public Health Network; Statistics Canada; Canadian Institute for Health Information Health Inequalities Data Tool. Available online: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/health-inequalities/data-tool/Index?Edi=2022&Cat=18&Ind=390&Lif=9&MS=36 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Barry, J.; Porter, L. Indigenous Recognition in State-Based Planning Systems: Understanding Textual Mediation in the Contact Zone. Plan. Theory 2011, 11, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.; Barry, J. Bounded Recognition: Urban Planning and the Textual Mediation of Indigenous Rights in Canada and Australia. Crit. Policy Stud. 2015, 9, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.K. The Gap between Text and Context: An Analysis of Ontario’s Indigenous Education Policy. Education 2015, 21, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, E.; Doyon, A. Language, Context, and Action: Exploring Equity and Justice Content in Vancouver Environmental Plans. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 1478–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemler, S. An Overview of Content Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2000, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, D.J.; Daoust-Filiatrault, L.-A. Better Than Good: Three Dimensions of Plan Quality. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2018, 38, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, R.K. Using Content Analysis to Evaluate Local Master Plans and Zoning Codes. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; Coburn, J.; Swartman, B. Plan Quality and Plan Detail of Visitor and Tourism Policies in Ontario Provincial Park Management Plans. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2014, 7–8, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, S.; Merrill, S.; Natcher, D. Ecosystem Management and Forestry Planning in Labrador: How Does Aboriginal Involvement Affect Management Plans? Can. J. For. Res. 2011, 41, 2247–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis. In International Encyclopedia of Communication; Barnouw, E., Gerbner, G., Schramm, W., Worth, T.L., Gross, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 1, pp. 403–407. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-5063-9566-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. FORUM Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, D.K.; Passelac-Ross, M. Water Rights and Water Stewardship: What about Aboriginal Peoples. LawNow 2010, 35, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Phare, M.-A.S. Denying the Source: The Crisis of First Nations Water Rights; Rocky Mountain Books Ltd.: Surrey, BC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, I.A.; Holley, M.; Caron, C.; Wood, J.; Gates, R.; Gallagher, J.; MacNeil, R.; Campbell, C. Report on the Licensing and Enforcement Practices of Manitoba Water Stewardship; Manitoba Ombudsman: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- von der Porten, S.; de Loë, R.C. Water Governance and Indigenous Governance: Towards a Synthesis. Indig. Policy J. 2013, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cuvelier, C.; Greenfield, C. The Integrated Watershed Management Planning Experience in Manitoba: The Local Conservation District Perspective. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2017, 33, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).