1. Introduction

In 1992, the International Conference on Water and the Environment (ICWE) emphasized the development of holistic approaches to integrated water management [

1] and all social, environmental, cultural, institutional, and political components related to resource management [

2]. However, achieving sustainable and equitable resource management systems is not possible without a solid foundation of good governance. This requires the concerted and specific participation of local authorities, the private sector, unions, NGOs, citizens, and academia [

1]. Comprehensive and collective participation will result in better management of resources at the watershed level. However, specific uses of resources (soils, forests, water, or fishing) have been privileged until these resources’ degradation and depletion [

3]. Yet, today, the quest for solutions to challenges through the adoption of inter- and transdisciplinary approaches is imperative [

1].

Global society requires that changes to people’s way of life occur; we must recognize the fundamental role of water in supporting ecosystems and the pressures exerted by human activities [

4]. Human well-being and progress toward sustainable development depend on the proper management of ecosystems to ensure their conservation amid growing demands for ecosystem services [

3]. More integrated, collaborative approaches to resource management can ensure greater sustainable development and better scientific knowledge by focusing on problem-solving in an integrated and satisfactory manner [

5].

Thus, a series of water and environmental resource management frameworks is essential for ensuring the sustainable and efficient use of natural resources. This series of frameworks has different purposes, with a high degree of robustness and reliability in facing all kinds of resource management challenges and issues. Diverse water and environmental resource management approaches may include considering the entire water cycle, adapting to and mitigating the impacts of climate change on water resources, addressing challenges resulting from population growth and increased water demand, and ensuring sustainable water supply and sanitation services in cities [

6,

7]. Although these generalizations are applicable, each specific framework should be tailored to the local context, considering factors such as water availability, socio-economic conditions, and environmental considerations [

8,

9,

10]. With this in mind, we aim to identify the best frame of reference for managing water and environmental resources. We must bear in mind that water and environmental issues are significant global concerns and can vary depending on the region. Water scarcity, water pollution, deteriorating water quality, inadequate sanitation, lack of access to clean water, groundwater depletion, and the impacts of climate change are some water-related problems that will require a multifaceted management approach that enables us to prioritize sustainable water use, promote water-saving technologies, invest in water treatment and sanitation infrastructure, and enhance awareness and education about water conservation and protection [

11,

12,

13].

Below, we will reference some works that address various elements used in our study, such as management theoretical frameworks, MCDM, and the frequency of integrated management concepts, since we could not find a single comprehensive work similar to the one that we propose. Guerrero et al. [

14] stated that the ecosystem approach (EA) to water management complements current thinking on IWRM, the two sets being consistent with each other; this is because EA principles have the potential to complement and enrich IWRM practice. Calizaya et al. [

15] identified the best solutions for existing conflicts in a region with problems concerning water scarcity, thereby promoting interaction with the parties in conflict and widening the scope to achieve a sustainable strategy. Using the AHP method and based on the evaluation of economic, social, and environmental criteria, Chávez and Osuna [

16] used the PROMETHEE method to carry out a ranking study in the countries of the European Union and determine which country is leading advances toward sustainable development; they did so by using a set of criteria that are in conflict with each other. Geng and Wardlaw [

17], in the context of IWRM, included economic, social, and environmental issues, applying MCDM to integrate different objectives in the planning, management, and decision-making process. They identified a variety of criteria in terms of economic, social, and environmental dimensions for use in their MCDM analysis. The GWP [

18] published a comparison of the relationship between the objectives of the WFD and those of IWRM, wherein experiences of implementation, a review of the progress made toward the adoption of IWRM in EU countries, and a review of the progress being made to comply with the WFD were collated. Widianingsih et al. [

19] analyzed the scientific literature on watershed governance through a bibliometric analysis using the Scopus database and the VOSviewer software, thus highlighting the quality and quantity of articles on basin governance around the world. Regarding word frequency, De Filippo et al. [

20], in their investigation of recurring key terms in IWRM and citizen science studies, found that the most used words were management, public participation and governance, sustainability, ecosystem, and conservation, all of which are related concepts within the field of water resources.

Our original idea was to consider articles from 1990 to the present (at least until 2022) in order to incorporate the highest number of references regarding management approaches. However, to our surprise, the documents consulted mainly referred to the four classic approaches (IWRM, WFD, EA, and Ecohealth) and, to a lesser extent, the WGP and SW. The search was challenging; we did not find many pertinent studies. Subsequently, the period was narrowed down to 2015 using the SW approach because we did not find many studies with similar characteristics to those shown in this work.

1.1. Motivation and Scope

The motivation for carrying out this study arose from the fact that we did not find any published works similar to the one we propose herein. We attempted to answer the question of which of the six integrated management theoretical frameworks is superior, using both qualitative and quantitative analyses of these integrated management concepts.

We were able to answer this question in two stages. The first consisted of using the AHP method, using our own experience in various sessions to qualitatively evaluate which of the six alternatives was the best. For this evaluation, five management criteria were used (governance, participation, sustainability, decentralization, and health and well-being).

Subsequently, the same question was answered again, only now we progressively increased the number of criteria from 10 to 25; having done so, it was no longer profitable to use the AHP method.

Thus, we decided to use two different multi-criteria methods, TOPSIS and PROMETHEE. The first method determines the distance between alternatives by finding the ideal solution and the non-ideal solution, and the second method determines this distance by ranking the different alternatives. For this reason, we counted the frequency of the most relevant management concepts from each theoretical framework, which served as inputs for the two MCDM methods. By evaluating the criteria, we were able to produce new results.

This work uses different water–environmental resource management approaches, the frequency of common concepts between the approaches consulted, and an MCDM evaluation. In several of the works consulted, we found that these topics were unlinked. For example, we did find related works with approach–approach, approach–MCDM, and approach–bibliometrics/frequency links.

1.2. Contributions

With our analysis, we were able to verify that the WGP and the SW are novel approaches that are superior to classical approaches. Both adopt particularities and contribute their own concepts, through which a more integrated approach is achieved.

Through principal components analysis applied to these management concepts, we observed that some concepts have low relative importance or are poorly represented.

Our analysis allowed us to confirm two groups. The first is made up of the WGP, Ecohealth, and EA, which are closely related, and the second is made up of IWRM, the SW, and the WFD. Through our analysis of the main components, we identified that both groups are independent. The former is more oriented to ecosystem management, and the latter to water resources.

According to FNWA [

1], it is important that the New Water Culture adopt a holistic approach to water management and recognize its multiple dimensions (i.e., the ethical, environmental, social, economic, and emotional values incorporated in aquatic ecosystems) to build and respond to the challenges of the 21st century.

1.3. Integrating Theoretical Frameworks

The great effort that has been put into the development of the six theoretical frameworks for the integrated management of water–environmental resources is admirable. However, it is both possible and recommended that these management approaches complement each other by incorporating elements from one or several other theoretical frameworks since they can strengthen the existing frameworks. For example, IWRM, which is oriented toward water resources, can be complemented by incorporating aspects of the EA, which refers to ecosystem services, the selection of species, and the loss of biodiversity. The WGP, which is oriented toward water governance, sustainable development, ecosystems, and health and well-being, can be complemented by incorporating aspects of the SW, such as adaptive and learning capacity, as well as distributive and procedural justice. Thus, the WFD, which refers to achieving good ecological status in water bodies, may be well complemented by aspects of Ecohealth, such as socio-ecological health, trans-disciplinarity, and social equity. This will promote a more comprehensive knowledge base in management approaches and allow a better approach to the problems and resources of basins. According to FNWC [

1], this will be achieved through the adoption of inter and transdisciplinary approaches. Other clear examples are the approaches proposed by Parkes et al. [

21] and Schneider et al. [

22].

1.4. Frameworks for Water–Environmental Resource Management

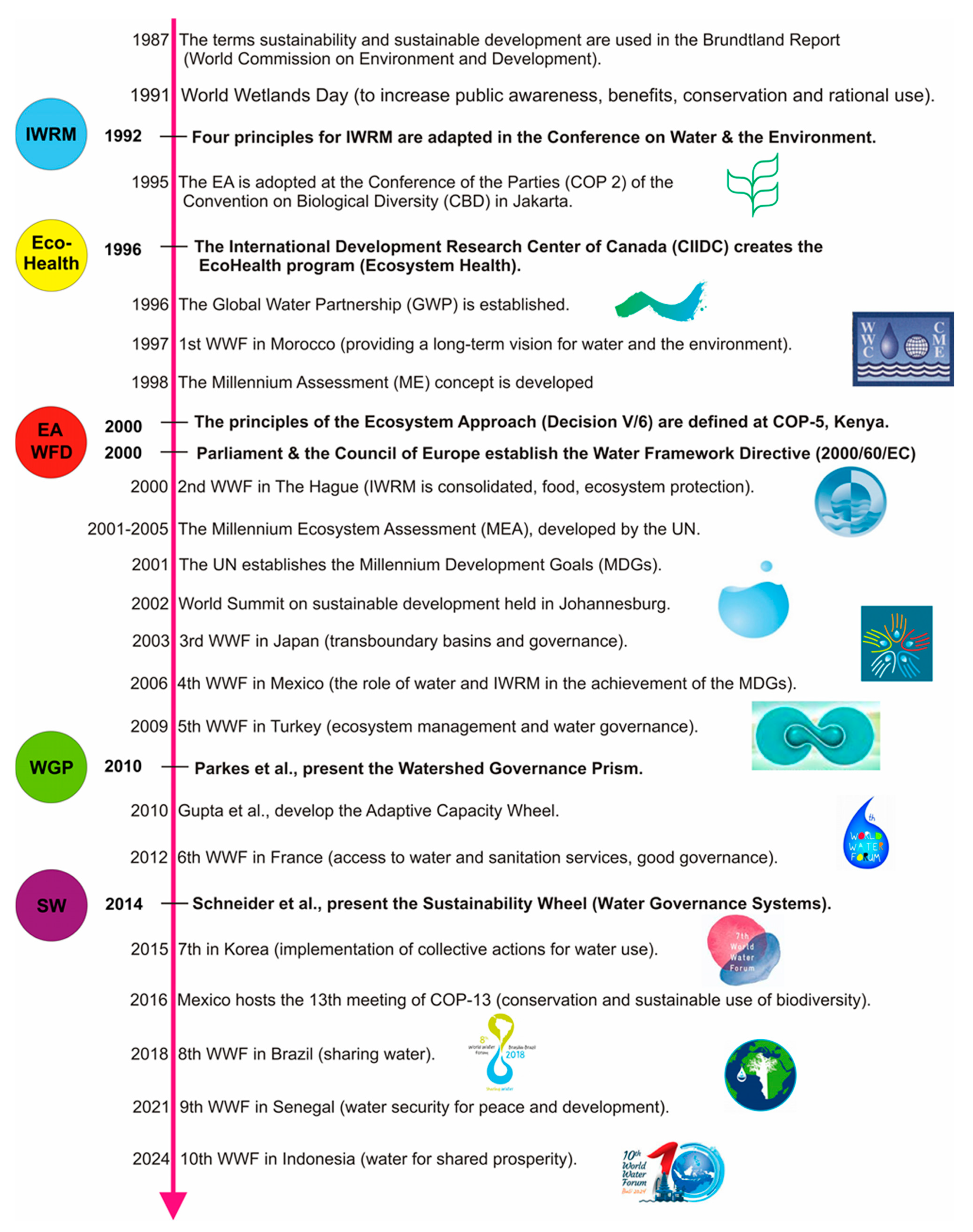

For a historical overview of the main water and environmental advances over four decades, highlighting the variety of frameworks, including Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) [

23], the Ecosystem Approach to Health (Ecohealth) [

24], the Ecosystem Approach (EA) [

25], and the Water Framework Directive (WFD) [

26], see

Figure 1. Typically, these have been issued by national or international government agencies. Some examples of these agencies are the International Conference on Water and the Environment (ICWE), International Development Research Center of Canada (IDRC), Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP-CBD), and Parliament and the Council of Europe, who established the Water Framework Directive. Parallel to such broader management approaches, the Watershed Governance Prism (WGP) [

21] and the Sustainability Wheel (SW) [

22] have primarily been developed by scientific research groups rather than governmental institutions (Health Sciences Programs, University of Northern British Columbia, Canada, and Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern, Switzerland), highlighting their peculiarity compared to the four existing approaches; the WGP and SW are more robust and incorporate new notions (e.g., water governance and water governance systems).

1.4.1. Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM)

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) made an urgent call for long-term environmental strategies to achieve sustainable development and effectively address environmental concerns [

27]. In 1992, the four principles of the Declaration of Dublin on Water and Sustainable Development were presented, and since then, they have become the strategic basis for IWRM [

23]. It is important to mention the four fundamental principles for water and sustainable development: (1) freshwater is a finite and vulnerable resource, essential to sustaining life, development, and the environment; (2) water development and management should be based on a participatory approach, involving users, planners, and policymakers at all levels; (3) women play a central part in the provision, management, and safeguarding of water; and (4) water has an economic value in all its competing uses and should be recognized as an economic good [

28,

29,

30]. These principles laid the foundation for integrated water resource management and sustainable development approaches. Accordingly, it is important to highlight that, to this day, they continue to guide global efforts in water management and underscore the importance of considering social, economic, and environmental aspects when addressing water challenges [

31]. IWRM involves a process that promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land, and related resources to maximize economic and social well-being in an equitable manner, without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems [

32]. Subsequently, the relationship between IWRM and sustainable development could be the next step toward a more coherent integration in water resource management [

5].

1.4.2. Ecosystem Approach to Human Health (Ecohealth)

The International Development Research Center (IDRC) established the Ecosystem Approaches to Human Health (Ecohealth) program in 1996–2001. The Ecohealth program was initiated by the IDRC in collaboration with several international partners [

24]. Its primary goal is to promote research and action that recognizes the intricate connections between ecosystems, human health, and sustainable development. Ecohealth emphasizes interdisciplinary and participatory approaches to address complex health issues within the context of ecosystems [

33]. It focuses on understanding the interactions between the ecological, social, and economic factors that influence human health and also supports research projects that integrate natural and social sciences, involving multiple stakeholders, such as researchers, communities, policymakers, and practitioners [

24]. Ecohealth suggests that human health and well-being are dependent on ecosystems, as both are the result of ecosystem management [

34]. For Webb et al. [

35], public health was not a clear focus before Ecohealth; however, now, it has been extended to other social, economic, and environmental spheres. When scientists from various disciplines become involved and participate in a community with decision makers, they can implement transdisciplinary research [

24,

36]. Since its establishment, the Ecohealth program has contributed to advancing the field of ecohealth and strengthening collaboration between researchers, educators, politicians, and communities in addressing health challenges within the broader context of the ecosystem [

24,

37].

1.4.3. Ecosystem Approach (EA)

In 2000, during the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) in Nairobi, Kenya, the concept of the Ecosystem Approach was conveyed at the global political level as a strategy for integrated management [

25]. The MEA, a comprehensive assessment of the world’s ecosystems, aimed to provide scientific insights into the consequences of ecosystem change for human well-being. One of the key suggestions of the MEA was the adoption of the Ecosystem Approach (EA) for the integrated management of land, water, and living resources. The EA recognizes that ecosystems are complex and interconnected systems and that their management should consider the interactions between ecological, social, and economic factors. It focuses on understanding and addressing the drivers of ecosystem change, as well as the impact of these changes on human well-being and the sustainable use of resources. Moreover, it encourages interdisciplinary collaboration, stakeholder engagement, and adaptive management strategies to foster the resilience and sustainability of ecosystems. The MEA’s recommendations and the promotion of the EA have since influenced global policies and frameworks, including the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The CBD recognizes the Ecosystem Approach as a key guiding principle for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. As mentioned above, people, water, and nature are part of the same system; therefore, any and all water policies must be incorporated into a comprehensive and systemic vision [

3,

25,

38,

39,

40,

41].

1.4.4. Water Framework Directive (WFD)

In 2005, the European Declaration for a New Water Culture (NWC) declared that rivers, lakes, wetlands, and aquifers should be considered biosphere heritage sites. Their management must thus be performed by communities and public institutions in a responsible and sustainable manner. The NWC proposes the conservation of ecosystems [

1] and clarifies and reinforces the proper implementation of the WFD [

42]. The European Water Framework Directive (WFD), adopted in 2000, is a key legislative instrument of the European Union (EU) that aims to achieve good water status for all European waters by 2027. It emphasizes integrated river basin management, the protection of aquatic ecosystems, and community involvement in decision-making processes [

26]. The objective of the WFD is that waters (rivers, lakes, estuaries, coastal waters, wetlands, aquifers) achieve an optimal ecological status through the application of hydrological basin plans (HBPs) intended to prevent water deterioration and prevent or limit the entry of pollutants into aquifers. There are six guiding principles of the WFD: (1) integrated river basin management; (2) environmental objectives and monitoring; (3) stakeholder involvement; (4) water-related planning and management measures; (5) economic analysis and cost recovery; and (6) international cooperation. This European water policy is an instrument for rational water management, establishing the natural limits of a basin and active citizen participation as a management unit [

1] and fostering the joint protection of surface and groundwater, inland, transitional, and coastal waters [

26,

43,

44,

45].

1.4.5. The Watershed Governance Prism (WGP)

Parkes et al. [

46,

47] proposed a theoretical framework called the Prism Framework of Health and Sustainability, which depicts the relationships between governance and development, ecosystems, social systems, and health. Later, Parkes et al. [

21] renamed it the Watershed Governance Prism, which integrates four different perspectives of water governance. Perspective A consists of water governance for sustainable development. Perspective B consists of water governance for ecosystems and well-being. Perspective C consists of water governance for the social determinants of health. Perspective D consists of water governance designed to promote socio-ecological health. The integration of and interaction between the four perspectives (A, B, C, and D) make up the Watershed Governance Prism (WGP), which facilitates integrated watershed governance and allows us to better understand the interactions between the four perspectives of water governance [

21,

48]. These perspectives aim to enhance understanding and decision making related to ecosystem health and sustainable water management. The prism encourages a transdisciplinary perspective and the integration of multiple stakeholders and knowledge domains in order to foster sustainable and resilient water management. The WGP is thus a contemporary approach that presents multiple facets of governance characterizing water resource management by linking social and environmental aspects with the determinants of health in a watershed context. The WGP is a tool for facilitating integrated watershed governance and understanding across four visions of water governance that also promote health, sustainability, and socio-ecological resilience [

21]; in addition, it is a useful approach for understanding complex links, specifically land–water interactions and the driving forces of change (floods, droughts) that exert pressures on socio-environmental systems [

19,

48]. A case of its application can be found in the work of Armas-Vargas et al. [

49].

1.4.6. The Sustainability Wheel (SW)

Schneider et al. [

22] and the Center for Development and Environment (CDE) developed a framework called the Sustainability Wheel. The Sustainability Wheel is a tool designed to support sustainability assessments and decision-making processes. It aims to provide a comprehensive and integrated view of sustainability by considering various dimensions and indicators. Moreover, it combines social, environmental, and economic dimensions to evaluate the sustainability of a particular context, project, or system. This approach is often depicted as a graphical representation, resembling a wheel with multiple spokes. Each spoke represents a specific dimension or aspect of sustainability, such as biodiversity, water resources, energy, livelihoods, governance, or equity. Within each dimension, relevant indicators or sub-indicators are identified to assess the sustainability performance of a particular area. The SW combines the transparent identification of sustainability principles, their regional contextualization based on their subprinciples (indicators), and the scoring of these indicators through deliberative dialog among an interdisciplinary team of researchers, which accounts for their various qualitative and quantitative research results. The SW is advantageous in its capacity for structuring complex and heterogeneous knowledge to attain a global perspective on water sustainability [

22]. A sustainable future for water is possible, although it depends largely on the social, economic, technical, and institutional reforms that stakeholders are willing to undertake [

50]. This approach (principles and indicators) is also applicable to other areas of study, and a case of its application can be found in the work of Schneider et al. [

51].

From this brief description of six theoretical frameworks used to address issues regarding water and environmental resources in watersheds, a natural question arises: which framework is the most effective? We were able to answer this question in two stages, as described in the following section. The first consisted of using the AHP method (i.e., the Analytic Hierarchy Process) to qualitatively evaluate which of the six alternatives was the best. For this evaluation, five management criteria were used (governance, participation, sustainability, decentralization, health and well-being). Subsequently, the same question was answered again, only we progressively increased the number of criteria from 10 to 25; in this context, it was no longer profitable to use the AHP method. Instead, we decided to use two different multi-criteria methods: TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) and PROMETHEE (Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluations). The first determines the distance between alternatives by finding the ideal solution and the non-ideal solution; the second does so by ranking the different alternatives.

1.5. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) Methods

There are different types of MCDM methods that have been developed by different authors in recent decades [

52,

53]. According to Pereira-Basílio et al. [

54], there are five methods that are most commonly used in various areas of knowledge (AHP, TOPSIS, VIKOR, PROMETHEE, and ANP); however, they highlight the AHP method. Below is the central idea of the MCDM method that we use in this work:

The AHP is a multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method [

55], widely used for evaluating and determining alternatives in problem-solving. It is a structured method that optimizes decision making when there are multiple attributes (criteria), doing so through the discretization of a problem. The AHP is a technique based on pairwise comparisons and is generally composed of four stages, defined below as the implementation procedure. Its application is simple; more details on this mathematical approach are provided by Saaty [

55], Triantaphyllou and Mann [

56], Blachowski [

57], and Bivina and Parida [

58].

TOPSIS is a multi-criteria method proposed by Hwang and Yoon [

59], used to determine the best alternative based on the concept of the compromise solution. Its main idea is to choose the best alternative that is nearest to the positive ideal solution (the optimal solution) and furthest from the negative ideal solution (the inferior solution). Then, the superior of these two is chosen and thereby deemed the best alternative.

PROMETHEE is a multi-criteria decision technique developed by Brans et al. [

60]; it is based on outranking techniques, through which we are able to study how good or bad an alternative is compared to another. It is one of the best-known and most widely applied outranking methods [

61] and generally follows the sequence (1) preference function; (2) comparison between alternatives; (3) alternative comparison; (4) criteria matrix, partial rankings; and (5) final ranking of alternatives [

62].

1.6. MCDM Associations

For Soares de Assis et al. [

63], the rise of new techniques and their integration with prior associations and fuzzy sets mean that decision makers now have just over 30 methods at their disposal. The main discrepancies between these methods are the complexity of the algorithms, the criteria weighting methods, the way in which preference evaluation criteria are represented, the possibility of uncertain data, and the type of data aggregation [

64].

Wątróbski et al. [

65] proposed a new method called the Data vARIability Assessment-Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (DARIA-TOPSIS). The TOPSIS method has shown its usefulness in solving multi-criteria decision-making problems in several domains [

66]. This fact, combined with the simplicity of its algorithm, contributed to the basis for developing a new multi-criteria method that considers the variability of the efficiencies of alternatives over time. The DARIA-TOPSIS method provides aggregated efficiency results regarding the performance of the evaluated alternatives, considering the dynamics of the changes within the investigated time range. The authors provide a publicly available library, called pydaria, for use in the Python environment.

The Characteristic Objects METhod (COMET) is based on Triangular Fuzzy Numbers (TFN) [

67]. A pairwise comparison of the determined Characteristic Objects (CO) enables relationships between criteria-based TFN to be established; the rule base is then defined and the preference values are calculated [

68,

69]. This method is completely free of the rank reversal phenomenon, much like the SPOTIS method [

70]. The SAPEVO method (Simple Aggregation of Preferences Expressed by Ordinal Vectors–Multiple Decision Makers) allows for the evaluation of a single decision maker. This advanced version extends the method to multiple decision makers; in addition, it introduces a process of standardization of the evaluation matrices, which increases the consistency of the model [

71]. Another method is COmplex PRoportional Assessment (COPRAS), which assumes a direct and proportional relationship between the importance of the decision variants examined [

72,

73]. This technique ranks alternatives based on their relative importance [

74].

The PROMETHEE methods are another family of superior methods, which include PROMETHEE I, II, III, IV, V, and VI, as well as GDSS, TRI, and CLUSTER [

75]. The modeling technique proposed by Moreira et al. [

76] determines a new extension present in the family of PROMETHEE methods, in which the integration of the original modeling of the method with the evaluation techniques by ordinal inputs of the SAPEVO method is carried out [

77]. This hybrid method represents the integration of two methodological concepts: one for cardinal evaluation (PROMETHEE) and the other for ordinal evaluation (SAPEVO) [

78,

79].

1.7. The Future Potential of MCDM

MCDA (Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis) methods are very useful, as they allow us to deal with multiple, often contradictory, criteria in a structured way and consider different preferences. In energy debates, there are many different, and often conflicting, sustainability criteria and viewpoints among stakeholders [

80]. The field of application of multi-criteria methods is wide and diverse. For example, they can be used to select sites for the installation of solar and wind power plants, assess the impact of volcanic hazards, select hotel locations for the tourism sector, select optimal irrigation plans, classify bridges affected by corrosion, manage water resources and health, and even aid in the selection of mobile devices. There is no limit to the field of their application; however, Villa-Silva et al. [

81] revealed, in their compilation from 1980 to 2018, that the sectors of greatest interest for the application of multi-criteria methods involve the selection of suppliers and projects.

Although there is extensive information on the web concerning the implementation of MCDM methods, either for self-teaching or storing in Excel sheets, Kizielewicz et al. [

82] developed an open source proposal for the Python 3 library called pymcdm. It is designed to address decision making using MCDA/MCDM approaches and includes classic and new methods for decision making. The library is available through the Python Package Index (PyPi) and is easy to install and update. It has also been uploaded to the GitLab repository under the MIT license, making it even more accessible. The pymcdm library consists of several modules designed for different MCDA/MCDM problems. It includes tools related to the evaluation of alternatives, the determination of optimal solutions and the relevance of criteria, comparative analysis, and visualization. Herein, we present a brief overview of the framework of the pymcdm library:

ARAS, COCOSO, CODAS, COMET, COPRAS, EDAS, MABAC, MAIRCA, MARCOS, MOORA, OCRA, PROMETHEE, SPOTIS, TOPSIS, and VIKOR.

Equal weights, entropy weights, standard deviation weights, MEREC, CRITIC, CILOS, IDOCRIW, angle weights, Gini weights, and variance weights.

Normalizations (eight normalization methods categorized by profit/cost criteria):

min–max, max, sum, vector, logarithmic, linear, nonlinear, and enhanced accuracy.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, Pearson correlation coefficient, weighted Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, rank similarity coefficient, Kendall rank correlation coefficient, and Goodman and Kruskal’s gamma coefficient.

COMET charts, weight charts, PROMETHEE charts, correlation charts, and ranking charts.

The provision of a wide range of approaches, the high performance and consistency of the software, and its small size are what distinguishes the pymcdm library from other software, making it a tool with great potential for decision makers [

82].

1.8. Use of Multi-Criteria Normalization Techniques

Normalization is a necessary step for the selection of an alternative or criterion; it has two attributes: cost (down) and benefit (up). Several normalization methods have been proposed, where

rij is the normalized value of

xij that represents the nominal value of attribute

j [

83]. The most recurrent normalization methods are min–max, max, sum, vector, logarithmic, linear, nonlinear, and enhanced accuracy [

82,

84,

85]. Several normalization techniques have been proposed, and some of them are used for specific MCDM methods. For example, the vector normalization method is used within the TOPSIS method, and the sum is implemented within the AHP. It should be noted that there is no consensus among researchers on the conditions in which to use each specific normalization technique [

85]. Some equations are linear, but the user is free to use other functions if they are considered to fit the problem better based on knowledge or experience [

86]. For example, Jahan and Edwards [

84] found just over 30 normalization methods, highlighting, in addition to the eight techniques already mentioned, the Markovic method [

87], Zavadskas and Turskis normalization [

88], the target-based normalization technique [

89], and the distance for target criteria [

90], among others.

In the study by Vafaei et al. [

85], the authors stated that max–min normalization is considered the best technique. However, they proposed a conceptual model to help decision makers select the most appropriate normalization technique for their decision-making problems. This model consists of three phases that distinguish the types of data from the matrices using different methods of normalization and the application of metrics (Euclidean distance, standard deviation, mean

ks (from a Pearson’s correlation), ranking consistency index, and mean squared error). Within our work, due to its scope, we used both our normalization methods and common methods used in multi-criteria methods, these being the semi-linear normalization method (vector) for TOPSIS, the linear normalization method (max–min) for PROMETHEE, and linear normalization (sum) for the AHP.