How to Resolve Transboundary River Water Sharing Disputes

Highlights

- The transboundary rivers in the world sometime cause conflict;

- Cooperation, mediation, river basin organisation, a proper monitoring system, information exchange, and benefit-sharing can resolve water-sharing disputes;

- Non-cooperation, disregard of international water laws, water hegemony, and the absence of formal institution or mediator are the causes for failure of transboundary river manage-ment;

- There is still dissatisfaction with 35% of transboundary rivers of the world;

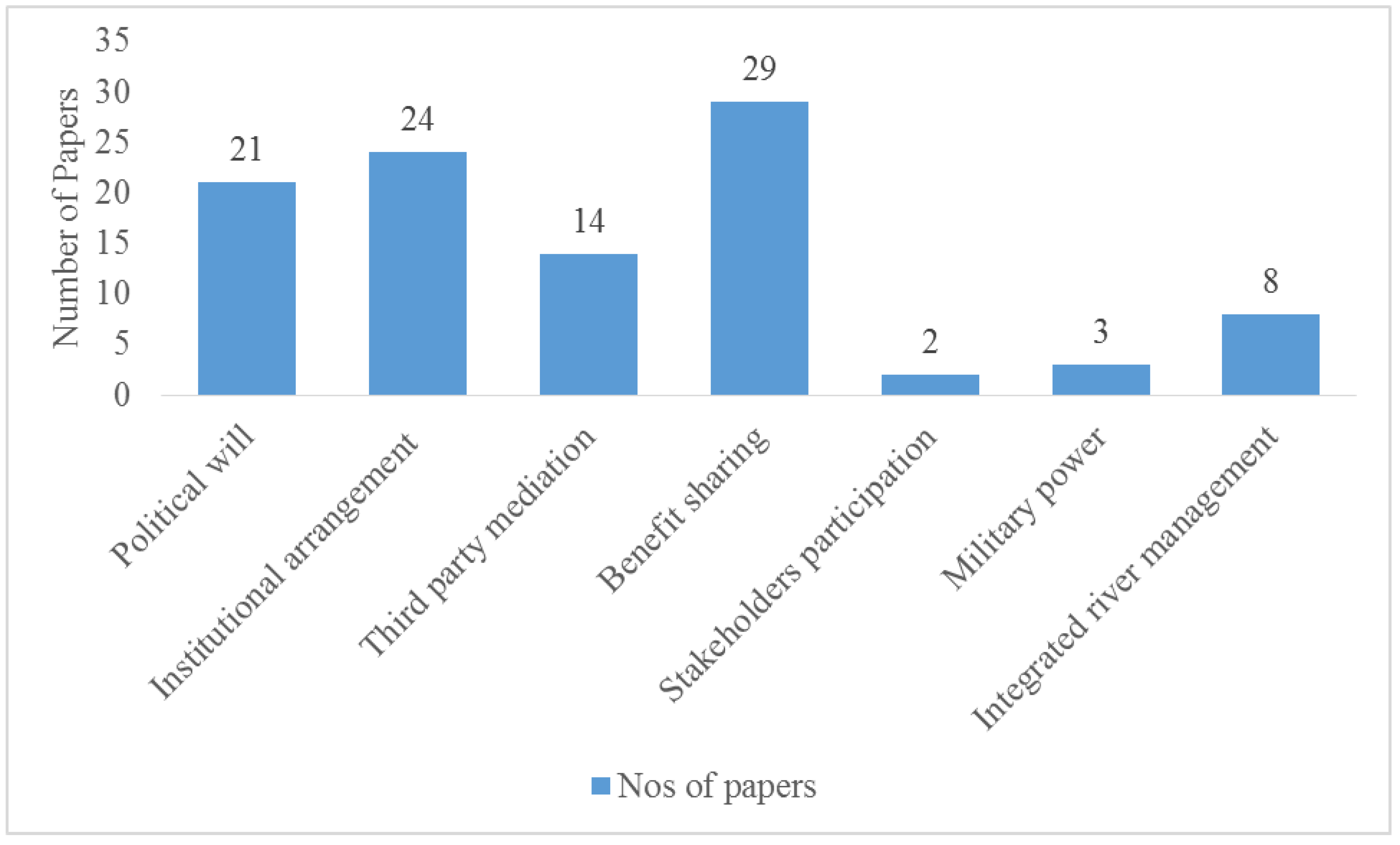

- The most effective technique for resolving water conflict is the benefit-sharing method.

- This study provides an idea of how to resolve the transboundary river water-sharing dis-pute.

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Scope of the Review

1.2. Objectives of the Review:

- ✓

- What are the methods used to resolve the transboundary river water-sharing disputes?

- ✓

- What is the most effective technique for resolving transboundary river water conflicts?

- ✓

- Which rivers are successful with respect to conflict management?

- ✓

- Which factors influence successful water agreements/treaties?

- ✓

- What are the causes for the failure of river basin management?

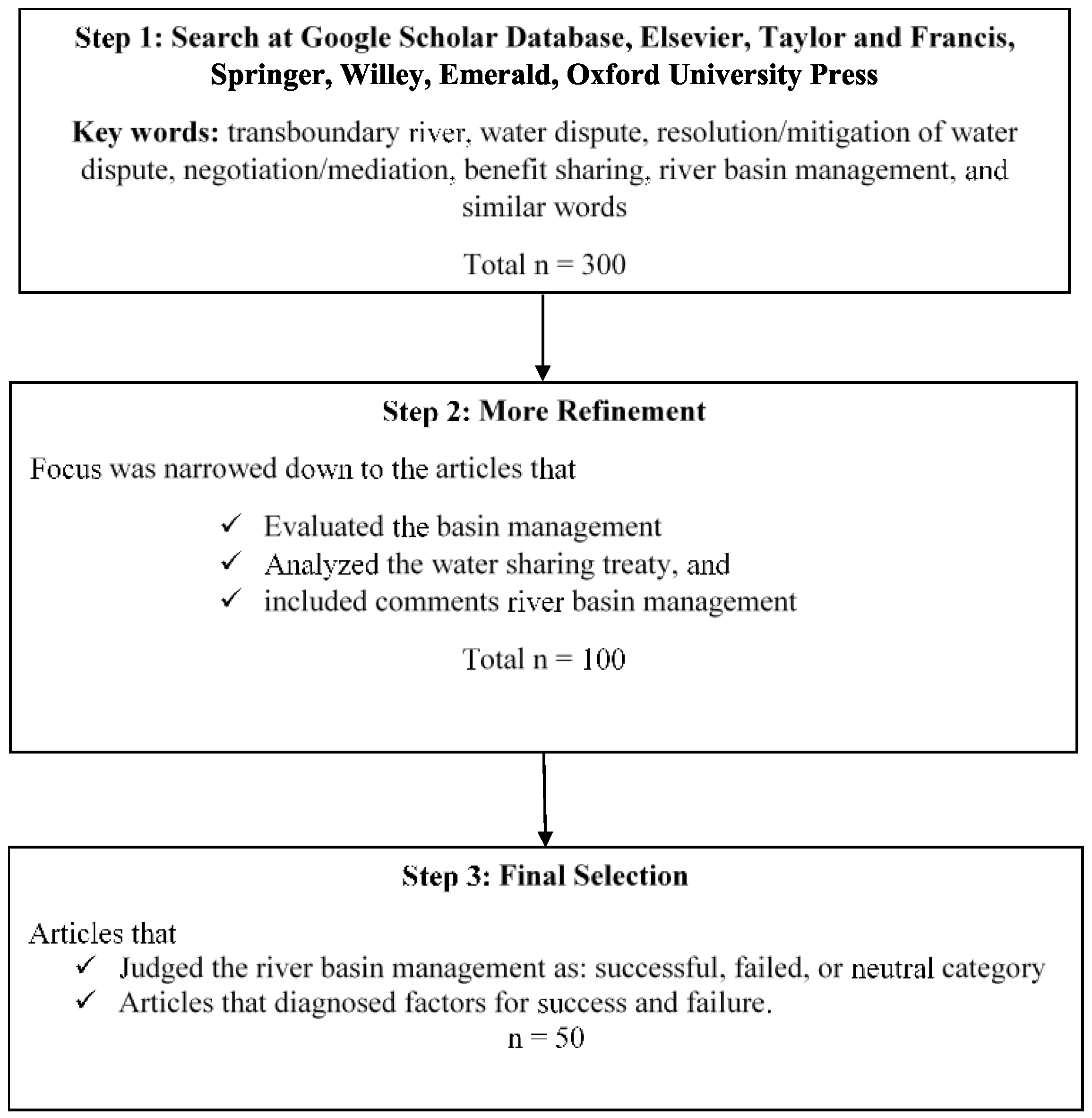

2. Methodology of Systematic Review

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Summary of the Review

3.2. Discussion

3.3. Benefit-Sharing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kasymov, S. Disputes Over Water Resources: A History of Conflict and Cooperation in Drainage Basins. Peace Confl. Stud. 2011, 18, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karner, M.A. Hydropolitics in the Jordan River Basin the Conflict and Cooperation Potential of Water in the Israe-li-Palestinian Conflict. Master’s Thesis, International Peace Studies, University of Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, A. Conflict and cooperation along international waterways. Water Policy 1998, 1, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.T. Trans-boundary Waters: Sharing Benefits, Lessons Learned. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Freshwater, Bonn, Germany, 3–7 December 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sadoff, C.W.; Grey, D. Beyond the river: The benefits of cooperation on international rivers. Water Policy 2002, 4, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen-Perlman, J.D.; Veilleux, J.C.; Wolf, A.T. International water conflict and cooperation: Challenges and opportunities. Water Int. 2017, 42, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, G.; Sindico, F. The Law of Transboundary Aquifers: Many Ways of Going Forward, but Only One Way of Standing Still, Review of European. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2014, 23, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadoff, C.W.; Grey, D. Cooperation on international rivers: A continuum for securing and sharing benefits. Water Int. 2005, 30, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abseno, M.M. Role and relevance of the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention in resolving transboundary water disputes in the Nile. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2013, 11, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mianabadi, H.; Mostert, E.; Pande, S.; van de Giesen, N. Weighted bankruptcy rules and transboundary water resources allocation. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 2303–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rai, S.P.; Wolf, A.T.; Sharma, N.; Tiwari, H. Hydropolitics in Transboundary Water Conflict and Cooperation. River System Analysis and Management; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorth, B. International Mekong River Basin: Events, Conflicts or Cooperation, and Policy Implications. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, L.; Petersen-Perlman, J.D.; Sproles, E.A.; Eynard, J.; Wolf, A.T. Assessment of transboundary river basins for potential hy-dro-political tensions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 45, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoffe, S.; Wolf, A.T.; Giordano, M. Conflict and cooperation over international freshwater resources: Indicators of basins at RISR. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2003, 39, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogren, K.L. Water Governance Process Assessment: Evaluating the Link between Decision Making Processes and Outcomes in the Columbia River Basin; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen-Perlman, J.D.; Wolf, A.T. Getting to the First Handshake: Enhancing Security by Initiating Cooperation in Transboundary River Basins. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2015, 51, 1688–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder. An Analysis of the Negotiations for the 1995 Mekong Agreement. Int. Negot. 2000, 5, 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahjahan, M.; Harvey, N. Integrated basin management for the Ganges: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2012, 10, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamner, J.H.; Wolf, A.T. Patterns in International Water Resource Treaties: The Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database. Colo. J. Int. Environ. Law Policy 1997, 8, 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, A.; Jafari, H.; Malekmohammadi, B.; Nasrabadi, T. Transboundary Water Resources Conflict Analysis Using Graph Model for Conflict Resolution: A Case Study—Harirud River. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 1720517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen-Perlman, J.D.; Veilleux, J.C.; Zentner, M.; Wolf, A.T. Case studies on water security: Analysis of system complexity and the role of institutions. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2012, 149, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischhendler, I.; Wolf, A.T.; Eckstein, G. The Role of Creative Language in Addressing Political Asymmetries: The Israeli-Arab Water Agreements; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, L.; Svendsen, M.; Giordano, M.; Steel, B.S.; Brown, B.; Wolf, A.T. Water governance benchmarking: Concepts and approach framework as applied to Middle East and North Africa countries. Water Policy 2014, 16, 1121–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Benefit sharing in the Mekong River basin. Water Int. 2014, 40, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.F. The Teesta River and Its Basin Area. In Water Use and Poverty Reduction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Ger-many, 2016; pp. 13–43. [Google Scholar]

- Afroz, R.; Rahman, M.A. Transboundary River water for Ganges and Teesta Rivers in Bangladesh: An assessment. Glob. Sci. Technol. J. 2013, 1, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kawser, M.A.; Samad, M.A. Political history of Farakka Barrage and its effects on environment in Bangladesh. Bdg. J. Glob. South 2016, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Asia Foundation. Political Economy Analysis of the Teesta River Basin; The Asia Foundation: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eskander, S.; Janus, T.; Barbier, E. Linking the Unlinked: Transboundary Water-Sharing Under Water-For-Leverage Negotiations. In Proceedings of the 2016 Agricultural and Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 31 July 31–2 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, K.D. Indian-Help-Sought-for-Nepal-Bangladesh-Trade. The Kathmandu Post, 10 April 2017. Available online: http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2017-04-10/indian-help-sought-for-nepal-bangladesh-trade.html (accessed on 10 April 2017).

- Nishat, A.; Faisal, I.M. An assessment of the institutional mechanisms for water negotiations in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna system. Int. Negot. 2000, 5, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.M. Integrated Ganges basin management: Conflict and hope for regional development. Water Policy 2009, 11, 168–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirsing, R.G.; Jasparro, C. River rivalry: Water disputes, resource insecurity and diplomatic deadlock in South Asia. Water Policy 2007, 9, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, Z. Resolution of Water Dispute Between India and Bangladesh: Does International Law Work? Law, York University: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, S.P.; Sharma, N. Benefit sharing approach for the transboundary Brahmaputra River basin in south Asia: A case study. Water Energy Int. 2016, 58, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, B.; Chauhan, M. The Transboundary Sundarbans Mangroves (India and Bangladesh); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dhungel, D.N.; Pun, S.B. The Nepal-India Water Relationship: Challenges; Institute for Integrated Development Studies (IIDS): Kathmandu, Nepal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, S. Rejuvenating the Ganga Basin: The Need to Implement GRBEMP. TerraGreen 2015, 8, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, A.; Dey, D. Water Woes in South East Asia: Geo-Ecology of Trans-Border River System and Dams between India and Nepal; Institute of Management Studies: Dehradun, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Beecham, S.; Zuppi, G.M. A model for water sharing in the Ganges River Basin. Water Environ. J. 2011, 26, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.N. Indus Water Disputes and India-Pakistan Relations. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Political Science, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zawahri, N. Third Party Mediation of International River Disputes: Lessons from the Indus River. Int. Negot. 2009, 14, 281–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.M.; A Zawahri, N. The effectiveness of treaty design in addressing water disputes. J. Peace Res. 2015, 52, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarfraz, H. Revisiting the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty. Water Int. 2013, 38, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eynon, K. Complex Interdependence: Watering Relations Between Ethiopia and Egypt; University of Cape Town: Capetown, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tafesse, T. Benefit-Sharing framework in transboundary river basins: The case of the eastern nile subbasin. In Improved Water and Land Management in the Ethiopian Highlands: Its Impact on Downstream Stakeholders Dependent on the Blue Nile; International Water Management Institute: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Arjoon, D.; Tilmant, A.; Herrmann, M. Sharing water and benefits in transboundary river basins. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 2135–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asmamaw, D.K. A critical review of integrated river basin management in the upper Blue Nile river basin: The case of Ethiopia. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2015, 13, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandalal, K.D.W.; Simonovic, S.P. State-of-the-Art Report on Systems Analysis Methods for Resolution of Conflicts in Water Resources Management; Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, The University of Western Ontario: London, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zawahri, N.A. Designing river commissions to implement treaties and manage water disputes: The story of the Joint Water Committee and Permanent Indus Commission. Water Int. 2008, 33, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilov, S.-M.; Varis, O.; Keskinen, M. Sharing Benefits in Transboundary Rivers: An Experimental Case Study of Central Asian Water-Energy-Agriculture Nexus. Water 2015, 7, 4778–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, F.; Huber-Lee, A. Liquid Assets: An Economic Approach for Water Management and Conflict Resolution in the Middle East and Beyond; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, Y.; Hu, W. Benefit Sharing on Transboundary Rivers: Case Study and Theoretical Exploration. J. Resour. Ecol. 2019, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Winston, Y. Benefit Sharing in International Rivers: Findings from the Senegal River Basin, the Columbia River Basin, and the Lesotho Highlands Water Project; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, D.; Mietton, M.; Hamerlynck, O.; Pesneaud, F.; Kane, A.; Coly, A.; Duvail, S.; Baba, M. Large dams and uncertainties: The case of the Senegal River (West Africa). Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 1108–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartle, A. Hydropower potential and development activities. Energy Policy 2002, 30, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, A.; Mosello, B.; Shalpykova, G.; Allan, A.; Clarvis, M.H.; Stoffel, M. Coping with changing water resources: The case of the Syr Darya river basin in Central Asia. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 43, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerich, K.; Van Rooijen, D.; Soliev, I.; Mukhamedova, N. Water Security in the Syr Darya Basin. Water 2015, 7, 4657–4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Name of the River Basin | Type (Countries Involved) | Evaluation (Evaluated by the Reference) | Factors for Success/Failure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any river basin | All rivers (no specific country) | Success | Political will and socioeconomic condition | [13,14] |

| Institutional arrangement | [23] | |||

| Benefit-sharing | [8] | |||

| The Mekong | Multi-Country (China, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam | Success | Political will and foreign policy interest | [17] |

| Mediation and funding by international organisation | [17] | |||

| Benefit-sharing | [5,18,24] | |||

| Failure | China and Myanmar are not included, unstable political situation, shift of policy, trend of bilateral negotiation, and absence of integrated basin management | [12,18] | ||

| The Teesta | Two-Country (India and Bangladesh) | Failure | Lack of political will, faith, and cooperation | [25,26,27,28] |

| Lack of benefit-sharing agreement | [29,30] | |||

| The Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna | Multi-Country (India, Nepal, Bhutan, China, and Bangladesh) | Failure | Lack of political will, faith, and cooperation | [14,31,32,33] |

| Disregard to water laws | [34] | |||

| Non-functional commission and lack of institutional arrangement | [31,32] | |||

| Lack of mediator | [31] | |||

| Lack of benefit-sharing arrangement | [18,32,33,35] | |||

| Lack of integrated management | [18,31,33,36] | |||

| Neutral | Lack of integrated management | [37,38] | ||

| Lack of benefit-sharing arrangement | [39,40] | |||

| The Indus | Two-Country (India and Pakistan) | Failure | Non-cooperative and non-functional commission | [14,41] |

| Success | Mediation by World Bank | [42] | ||

| Riparian countries are equally strong | [43] | |||

| Conflict-resolution mechanism | [4,44] | |||

| Neutral | Lack of benefit-sharing, integrated development, and third-party mediation | [4,44] | ||

| The Euphrates–Tigris | Multi-Country (Iraq, Syria, and Turkey) | Failure | Absence of mediator and non-functional commission | [16,43] |

| Lack of benefit-sharing | [45] | |||

| The Jordan | Multi-Country (Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria) | Neutral | Third-party mediation and military power | [4,21] |

| Failure | Lack of monitoring and conflict-resolution mechanism | [43] | ||

| [2] | ||||

| The Eastern Nile | Multi-Country | Success | A strong institution | [46] |

| Interdependence of the riparian countries, pressure from GCC, USA, and other external agents, and political will | [6] | |||

| Benefit-sharing (exchange of power and agricultural products) | [6,21,45,46,47] | |||

| Neutral | Upstream–downstream linkage, strong institution, and stakeholders’ participation | [48] | ||

| The Zambezi | Multi-Country | Success | Mediated by UNEP, | [42] |

| Institutional arrangement, benefit-sharing | [21,42] | |||

| The Senegal | Multi-Country | Success | Benefit-sharing | [5] |

| The Rhyne | Multi-Country | Success | Benefit-sharing | [5] |

| The Danube River | Multi-Country | Success | Benefit-sharing | [5,49] |

| Rivers between the USA and Canada | Two-Country | Success | Cooperation and third-party mediation, | [4,31] |

| Benefit-sharing | [4,21,49] | |||

| Institutional arrangement | [4,15,21,31,43] | |||

| Rivers between the USA and Mexico | Two-Country | Success | Cooperation and institutional arrangement | [31] |

| The Murray-Darling | Multi-State | Success | Political commitment, mutual trust, and stakeholders’ participation | [18] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hossen, M.A.; Connor, J.; Ahammed, F. How to Resolve Transboundary River Water Sharing Disputes. Water 2023, 15, 2630. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15142630

Hossen MA, Connor J, Ahammed F. How to Resolve Transboundary River Water Sharing Disputes. Water. 2023; 15(14):2630. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15142630

Chicago/Turabian StyleHossen, Mohammad A., Jeff Connor, and Faisal Ahammed. 2023. "How to Resolve Transboundary River Water Sharing Disputes" Water 15, no. 14: 2630. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15142630

APA StyleHossen, M. A., Connor, J., & Ahammed, F. (2023). How to Resolve Transboundary River Water Sharing Disputes. Water, 15(14), 2630. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15142630