Abstract

To undertake the modernization of Azerbaijan’s water sector, the government of Azerbaijan collaborated with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) in a comprehensive initiative to explore stakeholder perceptions on in-country water governance. The research approach, designed by national water experts and the authors, resulted in the development and administration of a stakeholder engagement and perception survey. The survey, implemented in 2022, elicited responses from a total of 219 state and non-state actors. To enrich interpretations of the survey, this study furthers the analysis of the government commissioned FAO stakeholder survey results and sheds additional insights as to where stakeholders see problems in water governance processes. This independent study informs the broader FAO project and generates supplemental recommendations to the Azerbaijani government for legislative and executive-level action to make Azerbaijan’s water sector more resilient as the climate changes and water insecurity increases. Even though an impressive number of 219 stakeholders participated in the survey, 80% of the responses were from state stakeholders, thus introducing significant bias into the dataset. In order to cope with the bias and make the best of the dataset, the authors analyzed the responses with a customized categorical methodology. Stakeholders were categorized into state, non-state, decision-maker, or executive groups and were examined for trends using various Pareto analyses. Interpretation of the survey responses reveals that, while stakeholders in the water sector interact through informal and formal means, stakeholder groups, to a large extent, lack an understanding of the barriers to stakeholder engagement in water-related policy matters. The stakeholders that indicate understanding of challenges accompanying water policy engagement note a lack of data, a lack of human and institutional capacity, and a lack of financial support to be some of the most common obstacles encountered in the sector. Furthermore, perceptions differ regarding the need for governance reform, the criticality of climate change, institutional resistance to change, policy or practice gaps, transparency, and variables needed for successful stakeholder engagement across all sectors. Such variations in perceptions illustrate the need for restructuring stakeholder interactive platforms and financial channeling to lead to better water governance and water management.

Keywords:

engagement; dissonance; alignment; policy; governance; stakeholders; bifurcation; climate change 1. Introduction

On 25 December 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev announced to the world that the Soviet Union had dissolved. Overnight, 15 new nation states appeared on global maps, officially marking the end of a powerful legacy. As each country forged national identities and policies, new struggles emerged because the collapse of the former Soviet empire created a regional vacuum []. For Azerbaijan, the “collapse of communist regimes…prompted significant changes in both environmental legislation and associated administrative structures;” the evaporation of the Soviet Union marked the end of socialistic centralized support in the area [,,,,,,,,].

Agriculturally, the post-Soviet transition manifested in substantial land reforms and the change of venerable agricultural practices in Azerbaijan. The Land Reform Act of 1996 permanently shifted the collective kolkhoz and sovkhoz resource management systems to privatized capitalistic enterprises to economically compete with the West [,,,,,,,,,,,]. Once these state-based management systems disappeared, so did the routine maintenance and upkeep of irrigation networks, which the country is struggling to deal with the consequences of today [,,]. Shifts in traditional agricultural management schemes, in combination with a large number of government entities managing water, have cultivated water governance systems riddled with fragmented and uncoordinated water management efforts []. Evidence of this agricultural and management structure—confirmed by a recent report issued by the FAO office in Baku, Azerbaijan (FAOAZ) (2021)—is still in place; governmental entities and non-state stakeholders do not collaborate on water management. Siloed perceptions persist that agency collaboration is not needed, given the independent management schemes that so many state and non-state agencies have utilized since the height of Soviet power [].

Azerbaijan is in a naturally arid region that is prone to climate-related extremes, including drought and flooding. For this reason, agriculture has relied on intensified irrigation schemes to manage water resources. Although irrigation is critical to the life of Azerbaijan’s agricultural economy, the Soviet-era irrigation networks—already old, poorly constructed, and dilapidated—fell into further disrepair after state-based management systems dissolved. Years of neglect mean that, as of 2022, nearly 1.4 million hectares of extensive irrigation and drainage networks are in dire need of reclamation to reduce the amount of water being lost in irrigation systems to the surrounding environment []. The state of the irrigation infrastructure and the current management practices all play a role in exacerbating water insecurity.

Climate-change modeling anticipates that the country’s water resources could diminish by as much as 20–25% over the next 60 years, which could also drop crop productivity by 15–20% or more []. Scientists estimate that some prone regions could see a decrease in crop productivity by 30–77% in worst-case-scenario modeling as drought intensifies and rainfall patterns change []. Food security will not be the only aspect of agriculture impacted by climate change. Although agriculture only comprises 5–7% of the country’s GDP, it employs 36–38% of the population, making agriculture Azerbaijan’s largest employer []. The World Bank (2021) reports that regional temperatures have been steadily increasing since the 1960s, contributing to the country’s 50% decrease in glacial resources []. If current water trends and irrigation systems remain unchanged food insecurity and water stress will intensify, directly impacting the country socially and economically.

Despite the obstacles to improving water resource management, the government of Azerbaijan is committed to reforming the capacity of its water institutions [,,,,,,]. The momentum to enhance water governance and to reform water management is accelerating due to climate change and Azerbaijan’s desire to achieve the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goal 6: clean water and sanitation for all. The Azerbaijan government has made substantial commitments to modernize its water sector by forming partnerships with various international development organizations such as the FAO. A major milestone occurred on 15 April 2020, via a presidential decree that established a new water commission, chaired by a deputy prime minister, to ensure water resource efficiency “by coordinating all water sector management activities” []. The water commission accomplishes its goals by coordinating and engaging ministries, state entities, and non-state domestic or international actors in water management. Following the establishment of a water commission at the highest level of government, the government solidified a partnership with the FAOAZ in 2021. The FAO–government partnership aims to study what actions can be taken by state or non-state stakeholders to reform water governance and other management schemes in the country to enhance agriculture and its water security resiliency.

Through combined international and local efforts, the FAO–government project developed looks at improving water governance to: (i) move towards sustainable agricultural development, (ii) enhance water security, (iii) fulfill the country’s commitments to the SDGs, and (iv) build a water governance framework and policy able to cope with the changes anticipated to accompany climate change. The methodology behind the FAO–government initiative involves the analysis of perspectives from stakeholders within the water sector.

Studying stakeholder perspectives is imperative, because diverse stakeholder engagement can identify problems, enrich solutions, and initiate new processes that are sustainable and meaningful in the long run. According to Akhmouch and Clavreul (2016), “stakeholder engagement has long been considered an integral part of sound governance processes,” which explains why the FAOAZ project attaches great importance to stakeholder perception research []. Stakeholder input can “[provide] unique experiences and perspectives…[to]…enrich decision-making in the country and ensure the success of water action” [,,]. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis by Lim et al. (2022) points out that one of the 12 principles of the OECD’s principles on water governance is stakeholder engagement; involving stakeholders can reveal “good practices” and initiate “reform process towards good water management at any level of the government or country.” Ultimately, engaging stakeholders can lead to informed and targeted action strategies that contribute to integrated water resources management (IWRM). IWRM is based on the key principles of “ecological sustainability, social equity, and economic efficiency.” Yet, according to Lim et al. (2022), implementing IWRM requires institutional collaboration, accommodation of varying sectoral water needs, holistic water policy that encompasses national security and the economy, and stakeholder engagement, hence IWRM relevancy []. The government of Azerbaijan acknowledges the key role of IWRM for the country’s reform efforts in its draft national water strategy, as indicated in its third national voluntary review of the achievement of SDGs [,,,,,]. Given the plethora of the literature that emphasizes the widespread benefits of engaging stakeholders and their perceptions, the FAO–government stakeholder survey study is a logical first step to enhance the systemic understanding needed to accomplish the water management goals delineated by the president’s water commission.

To summarize, Azerbaijan inherited the Soviet water governance structure, of which the country are still feeling the effects to this day. Soviet water governance never designated one branch to spearhead water resource management efforts, thus government ministries involved in water work have normalized having no collaboration with other national, state, or local stakeholders in the water sector. Poor coordination among governmental entities, in combination with new non-centrally managed water systems installed in 1996, has culminated in water systems that exacerbate water insecurity. Although regionally prone to drought and dependent on failing irrigation schemes, climate-change modeling suggests that regional temperatures and drought will increase over the next 60 years, further stressing water resources in the country. Concerned about the future, the government of Azerbaijan is utilizing stakeholder analysis as a means of understanding how their current governance practices can improve to make the country’s water sector more resilient in the face of a water insecure future. This international collaborative effort is so significant because it is arguably one of the country’s first high-profile public efforts to engage multiple water stakeholders and capture their perceptions regarding where barriers are embedded in current governance systems to inform future policy development and targeted action strategies. Given this context, this independent analysis aids the Azerbaijan national project aimed to enhance water governance by summarizing water stakeholder perceptions and suggesting a path forward, given the survey findings to inform the recommendations of the broader FAO–government of Azerbaijan project.

2. Methods

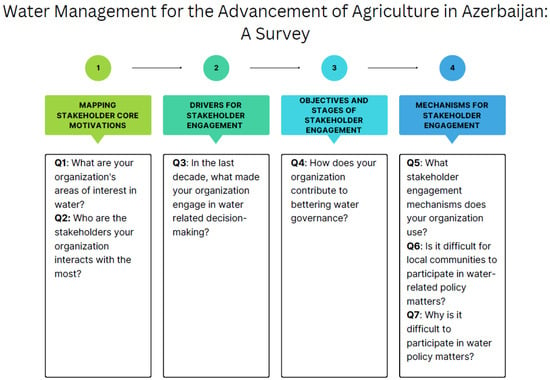

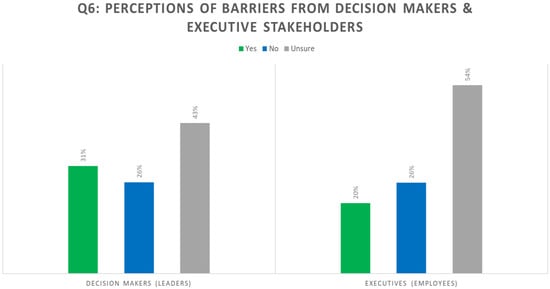

In total, the survey was co-designed by the authors and the FAOAZ team in collaboration with high-level state officials over the course of 7 months. The survey, consisting of 21 questions (Figure 1), was inspired by two international survey efforts to pinpoint effective water management: the 2015 2015 OECD Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance and the Water Policy Group’s Global Water Leader survey [,]. The FAOAZ survey derives inspiration from both surveys, because they aim to also understand how various water challenges and risks are viewed through the diverse lens of different stakeholders to inform future water action. The demographic indicators of the stakeholders reported include their age range, organizational representation, and organizational category (decision maker or executor).

Figure 1.

An overview of the FAOAZ stakeholder perception and engagement survey.

The survey was built on an online survey design platform (Google Forms) and then administered for stakeholders to complete online by the regional FAOAZ team. The FAOAZ team handled the online survey design and electronically disseminated the survey for translation purposes and the team’s expertise in navigating stakeholder relationships. In April 2022, the survey went live and was disseminated to approximately 600 stakeholders from all aspects of the Azerbaijan water sector (Table 1).

Table 1.

A summarized list of stakeholders surveyed and the institutions represented.

After 4 weeks, the survey received responses from 219 stakeholder participants. Out of the 219 survey respondents, over half of the respondents (54%) reported working for the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), a state entity. The remaining major stakeholders of note included the amelioration and water management group (OJSC) (16%), scientific institutions and groups (15.5%), and the drinking water utility (Azersu) group (7%). Other stakeholders representing NGOs and private businesses and other state actors such as the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources (MENR), the power utility group (Azerenerji), the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), and the Agrarian Credit/Development Agency participated in the questionnaire, but their participation combined represented 6% of the total response. Individually, each non-major represented stakeholder group (NGOs, private businesses, MENR, Azerenerji, and MoPH) represented less than 1% of the aggregate group response. In total, if the stakeholders were shuffled into state and non-state categories, 80% of the survey responses reflected state actor perceptions, with the remaining 20% representing non-state actor opinions.

The high participation rate of state actors in this analysis is a critical nuance to note, because state gross participation rates skew interpretations of the data, since over half of the participants belong to the MoA. This data bias necessitates methodology that places more weight on the results of designed bifurcated groups (state vs. non-state and decision makers vs. executives) than the agglomerate group response. A summarized breakdown of how the data is filtered and analyzed by the authors to accommodate the challenges provided by a data skew is shown below:

- Category/Filter 1, The Data as a Whole: examination of the entire dataset for general trends and correlations.

- Category/Filter 2, Designated Stakeholder Comparisons: Sectoral analysis based on the respective bases of major respondent groups: agriculture, water management, drinking water and sanitation, and science and technology. This filter helps pinpoint sector-specific issues and perceptions related to water.

- Category/Filter 3, Designated Group Comparisons: State vs. non-state and decision makers vs. executive stakeholder grouping. This filter helps understand the barriers and opportunities that exist along the borders between service providers and beneficiaries on the one hand and between policy and practice on the other hand.

Stakeholders referred to as state actors represent government agencies at local, state, and federal levels, while non-state actors are stakeholders that are not affiliated with or employed by government entities, e.g., water user associations (WUA/WAA) (WUA/WAA are non-governmental groups established by government entities to play a role in managing water on localized levels by collecting water fees and solving disputes between water users [], private business entities, NGOs, and academic communities. Data from decision makers and executives are also examined and compared, because these two categorizations reflect the opinions of a leader versus a practitioner in a workspace on water issues. These groups are important to analyze, as both groups interact differently with water policies and issues because of their proximity to water works. For the purposes of this analysis, Filters 1 and 3 will be the primary lenses applied to evaluate the data.

3. Results

The majority of stakeholders indicate that irrigation and farming, as well as water supplies for irrigation water use, are the primary focus of their organizational agenda. Other stakeholder water interests that emerge from the survey include drinking water, industrial water use, water quality, and general environmental water impacts. Looking at all the designated stakeholder organizational interests (disclosed in survey Question 2) reveals that stakeholder interests are broad and often interlinked; most stakeholders indicate more than one area of organizational interest. Furthermore, the survey reveals that organizations have interests or concerns regarding potential detrimental hydrological impacts to humans linked to climate change. As for the nature of the organizational water action, 26% of stakeholders indicate that their organizational action has stemmed from water or emergency crisis response, e.g., drought and flooding over the course of the last decade. An additional 22% of respondents selected that their organizational water decision making has revolved around water-use conflicts in irrigation, which is also linked to climate change, given what is known about regional drought intensification, water use intensification, and failing irrigation infrastructure. Out of the aggregate survey response, 20% of stakeholders express that climate change drivers pose the single greatest challenge to effective water management.

Stakeholder opinions reveal that interactions with other stakeholders are occurring at localized levels, since farmers and agricultural entities (WUA/WAA) are the parties most notably interacted with. Evidence of state and non-state vertical mixing is visible in the number of times that stakeholders indicate their interaction with municipalities and local executive powers (the key players in environmental and agricultural regulation or enforcement). Survey respondents denote that the primary platforms of cross-stakeholder engagement include informal and formal meetings, WUA/WAA organization, workshops and training, surveys, polls, and consultations, which are how national, state, and local stakeholders are vertically and horizontally mixing. Although the survey results imply that successful information exchanges occur among government officials, non-state actors, and local water users, stakeholders convey a broad lack of understanding of their counterparts in the survey.

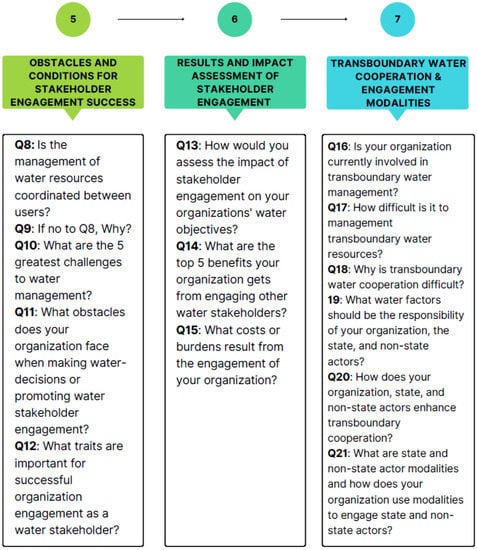

Given the information regarding the platforms in use by stakeholders and given the frequency of localized and national cross-sectoral interactions, stakeholder perceptions should reflect awareness of the challenges that community members face when it comes to participating in policy making at localized levels; however, this is not the case. The agglomerate group response reveals that, out of 219 responses, 111 (51%) of stakeholders reveal that they have no idea whether it is difficult or not for community members to participate in water policy matters (Question 6). Bifurcating the data into groups shows that 54% of the state actor group communicate barrier uncertainty, while 27% believe no barriers exist for community participation (Figure 2). The non-state actor group results echo similar uncertainty; combined, 60% of the non-state actors also perceive no problems or are uncertain about the barriers to community participation. However, 40% of the non-state actors express that barriers exist that discourage water policy engagement, which is higher than what the state actors see.

Figure 2.

State vs. non-state designated group comparison for Question 6.

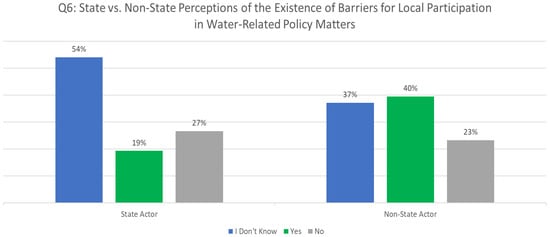

Of the 219 respondents, 30% of the stakeholders self-identify on the survey as decision makers (leaders); the remaining 70% self-identify as executives (practitioners/employees). Categorizing data into these two groups and analyzing them is important because of the insights that can be derived from the perspectives of these groups. Stakeholders in self-identified employee or leadership roles are denoting their placement in the hierarchy of their workspace and assuming that leaders oversee or manage employees. Different roles and responsibilities assigned to work roles will generate varying perspectives, which bifurcation aims to capture. For example, looking at the decision maker versus executive perspectives reveals that executives could see their role in decision making to be insignificant in the local water management scheme because of their poor awareness surrounding barriers to participation in comparison with their leaders. The majority of executive respondents (80%) express little to no ability to be able to identify barriers present in localized participation regarding water-related policy matters (Figure 3). Decision makers or leaders are arguably the driving forces behind water projects or are actively developing water policies, potentially explaining the 11% difference in the perceptions of the barriers that exist that people encounter. Decision makers who spearhead project or policy initiatives should have awareness of the challenges that communities face, because obstacles affecting communities can affect project development and work timelines. Although the consensus between both groups indicates a unilateral barrier uncertainty, the decision makers demonstrate a slightly higher level of understanding of the barriers that face local participation in the development of water policy.

Figure 3.

Decision maker vs. executive group comparison for Question 6.

Overall, the lack of perceived barriers reveals not only a disconnect or likely breakdown between state and local stakeholder understanding but also a lack of understanding across all demographic groups regarding community water policy participation inhibitors. The disconnect captured in Question 6 reflects what is already known, i.e., that Soviet siloed water management lingers, contributing to disconnect and poor understanding among water stakeholders. The lack of awareness demonstrated by the respondents is concerning, therefore enhancing the resiliency of future water policy in the country will require measures to address the detachment that exists within upper echelon levels of national policy and rulemaking from localized aspects of management.

Eighty (37%) stakeholders gave a follow-up response in Question 7 regarding the specific difficulties that they perceive local communities face when trying to become more active participants in water policy matters. This relatively low level of stakeholder feedback can be seen as aligning with the respondents’ broad acknowledgement of not fully understanding the hurdles that exist for community participation. However, the low stakeholder response rate to this survey question yields just as much information as the survey questions that receive a high response rate for two reasons: first, the results and lack of input confirm the earlier finding that stakeholders do not fully understand the barriers to engagement in water policy; second, the stakeholders that did respond felt confident enough to do so. Confidence likely implies expertise, providing a more comprehensive representation of what is happening at localized levels. Out of the 10 designated barriers listed in Question 7, the top 3 barriers selected by the agglomerate response are: lack of data and information, lack of financing, and lack of human or institutional capacity. The lack of human or institutional capacity does not explicitly represent a commentary on problems with governance, but the denotation of poor capacity could stem from underlying governance issues that deserve further examination.

Throughout the survey responses, concerns emerge regarding the effects of climate change and the perceived risk it poses to water and agricultural systems. Question 10 specifically reveals these insights, as the question requires participants to review a list of challenges and to rank the pre-listed difficulties that they pose on a scale of one to five (one representing the greatest challenge and five representing a lesser challenge). Out of the agglomerate total, the top five challenges that emerge are:

- Climate change driver factors (20%).

- Resistance from certain sectors/entities to reform (13%).

- Weak public participation in water governance (9%).

- Water issues being low priority in public policy (9%).

- Fragmented water institutions (9%).

The perceived challenges noted by stakeholders are the first commentaries, although indirect, provided by stakeholders that can be tied to water governance. Stakeholder answers expose institutional rigidity, poor cohesion, water issues or priority misunderstanding, and little diversity in current water governance systems.

Challenges not perceived to be problematic include a lack of cooperation between countries and a lack of data and information. A lack of data and information not perceived to be a challenge to water management juxtaposes other stakeholder responses that denote a lack of data to be a barrier to community engagement in water policy matters. The differing perceptions that emerge pertaining to the degree of challenges posed by data and information variables further the reality of the lack of understanding presiding among all water stakeholders. Answers to Questions 10 and 7 reveal that missing data and information are perceived to be barriers to local participation in water-related policy matters but are not necessarily perceived to be challenges regarding the effective overall management of water in the country. The discrepancy is meaningful as it could highlight the data weaknesses generated by the skew or it could reveal deeper insights regarding the disconnect among the challenges felt at national, state, and local levels.

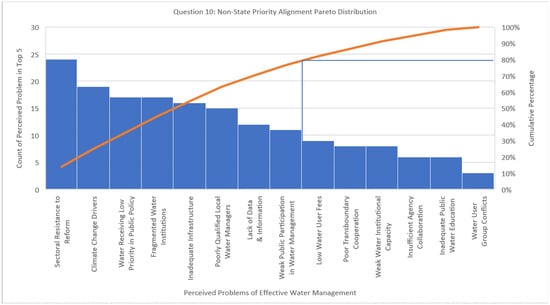

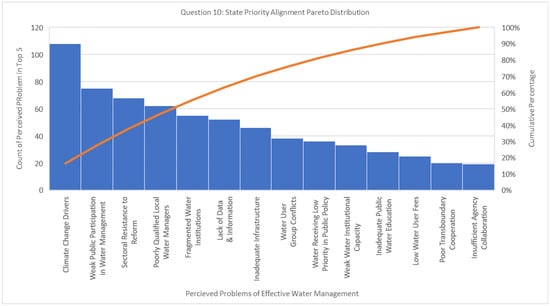

To analyze state, non-state, executive, and decision-making responses further, the bifurcated groups’ results manifest in Pareto charts (the Pareto principle specifies that 80% of consequences come from 20% of the causes, asserting an unequal relationship between inputs and outputs), as seen in Figure 4 and Figure 5, rooted in the principle of the 80/20 rule. In this context, the Pareto graphs assist in focusing on the vital few problems that the visualized groups perceive as being a priority. A horizontal and vertical line have been added to Figure 4 to better explain how to interpret the Pareto graphs.

Figure 4.

Designated non-state group response of water management challenges (Question 10).

Figure 5.

Designated state group response of water management challenges (Question 10).

The vertical line has been placed where the cumulative percentage line and the horizontal line (at 80%) meet; all of the x-axis categories to the left of the vertical line therefore are considered to be important to 80% of respondents. The reader needs to note that, if the vertical line intersects with the cumulative percentage line closer to the right than the left, it can be interpreted that there is a weak consensus within the group around which challenges have the most impact.

A Pareto analysis tells a more complex narrative and allows the extraction of data insights that are lost in standard bar charts. The height of each bar marks the frequency of input received from either non-state or state actors, thus higher bars mean that a specific challenge received more attention from stakeholders than identified challenges with lower bars. The 80/20 rule manifestation in the Pareto charts also helps to visually identify which issues need to be addressed first, resulting in the most positive or meaningful change. The Pareto charts in Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate both state and non-state actor perspectives on challenges to water management. Please note that the simplified statistical approach utilized in this analysis is not intended to remedy weaknesses or to fix the challenges presented by a skewed dataset; instead, the quantitative approach chosen aims to make the best of the dataset by reorganizing the data in a way to yield potential insights.

The charts reflect the same insights as the agglomerate but reflect slight disparities in perception. Non-state and state groups perceive climate change drivers to be one of the top challenges to water management, but the non-state group sees the sectoral resistance to reform as a bigger issue than the problems posed by the drivers of climate change. Sectoral resistance is a concern also for the state actors, showing a strong third place in Figure 5. Non-state actors see the fragmentation in the water sector and water as a low priority in public policy to be a greater problem than the state actors do; this can be viewed as a non-state commentary on water governance in place. State actors point to the weak public participation in water matters and poorly qualified water managers as some contributors to sustainably managing water in Azerbaijan. Although not a direct commentary on water governance, these variations in perceptions hint at the possibility of the perceptions that state actors could have regarding their non-state counterparts. The results suggest that future stakeholder analysis should examine the presence of social attribution theory among groups to better determine whether non-state actors are attributing problems to the state and vice versa.

Since the vertical line in Figure 4 and Figure 5 intersects with the cumulative percentage line farther to the right than the left, it can be surmised that there is a weak degree of consensus within the groups concerning which challenges have the most impact.

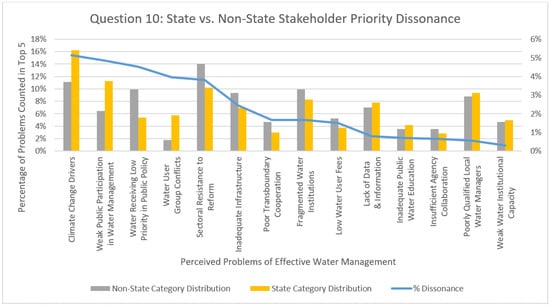

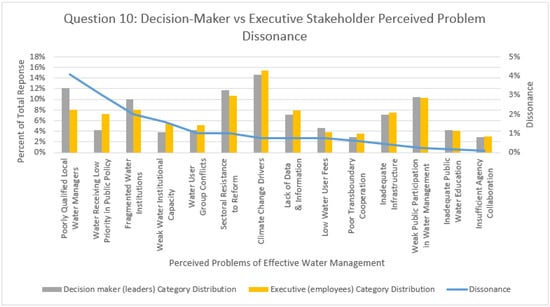

Given this interpretation, the following Pareto charts pivot and take the analysis in this study one step further by looking at group dissonance rather than juxtaposing the vital few from each group (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

State vs. non-state response agreement on water management challenges (Question 10).

Figure 7.

Decision-maker vs. executive stakeholder response agreement on water management challenges (Question 10).

Figure 6 compares the distribution of responses. This distribution represents the frequency of responses by the perceived problem as a percentage of the total number of responses for an individual stakeholder group in order to normalize any difference in volume of respondents between compared groups. The “Dissonance” line is plotted on the secondary y-axis and visualizes the difference between the distribution of responses of the two groups. This descending line allows a visual representation of dissonance or alignment between the two groups on a given perceived problem with higher dissonance. Subsequently, this can be interpreted to be a larger difference in top perceived problems and a lower dissonance interpreted as more alignment between the two groups. Dissonance between the group response ranges between 0 and 5%, with some groups experiencing a difference in dissonance by 1%. Though the scales are relative, the results still allow groups to prioritize the categories that require more attention in alignment or categories that can be prioritized as opportunities for accelerated improvement as data continue to be gathered. Please note that these relative percentages are not a measure of data strength but are rather the alignment or dissonance. As such, using the word “high” or “low” is only interpreted relative to another value.

Breaking down Figure 6 reveals several pieces of critical insights regarding the state and non-state actor groups.

- Despite both groups displaying a lower section of their respective distributions, state and non-state actor perspectives align regarding the following challenges that impact effective water management:

- Weak water institutional capacity (0% dissonance).

- Poorly qualified water managers (1% dissonance).

- Insufficient agency collaboration (1% dissonance).

- Lack of data and information availability (1% dissonance).

- State and non-state actors are less aligned on challenges pertaining to:

- Climate change (5% dissonance).

- Water being a low priority in public policy (5% dissonance).

- Little public participation in water management (5% dissonance).

- Water user group conflicts (4% dissonance).

- Sectoral resistance to reform (4% dissonance).

Upon first impressions, the dissonance in perception regarding the challenge that climate change poses to water management between the state and non-state actors is disorienting; throughout the duration of the survey, stakeholders acknowledge the seriousness of threats posed by climate change. The climate change dissonance between the state and non-state stakeholder groups in Figure 6 does not discount collective stakeholder perceptions regarding climate change. Instead, what Figure 6 highlights is that state and non-state groups have perspectives that differ pertaining to the degree of challenge posed by climate change.

The decision maker versus executive stakeholder analysis (Figure 7) reveals that overall decision-maker and executive perceptions align regarding the challenges posed by: insufficient agency collaboration (0% dissonance), inadequate public water awareness or education (0% dissonance), weak public participation in water management (0% dissonance), and inadequate infrastructure (0% dissonance). The evident dissonance reveals that the bifurcated group perspectives do not align, as they pertain to poorly qualified water managers (4% dissonance), water receiving low priority in public policy (3% dissonance), fragmented water institutions (2% dissonance), and water user group conflicts (2% dissonance).

So far, the majority of this analysis reviews the stakeholder perceptions regarding the problems and challenges that the water sector faces in Azerbaijan. However, the survey also aims to ascertain opinions regarding strategies that can successfully engage stakeholders, as well as reveal the trade-offs (benefits and costs) that can arise from cooperation efforts. Stakeholders note that one of the top characteristics needed to support efficient stakeholder participation is decision-making ability (decision-making ability is defined as those engaged in the process to take/make decisions). Decision-making ability, in combination with process neutrality characteristics, accounts for 32% of the total stakeholder response, but transparency is arguably the most important characteristic to support stakeholder engagement. Even though 11% of stakeholders directly selected objective transparency and achievement, transparency is inherently linked to all of the characteristics required for success because it aids neutrality, communication, financial resource use efficiency, and quality and availability of information available for stakeholders to digest for decision making.

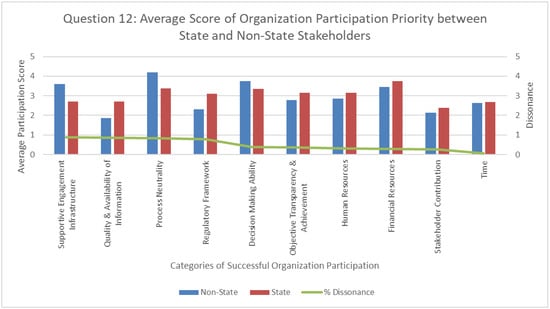

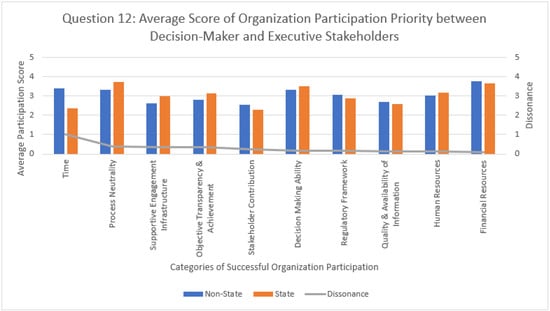

Bifurcating Question 12 data for analysis (“Average Participation Score” is the sum of ratings (4 = higher, 1 = lower) divided by the number of times the category was rated) reveals a diverse response from the survey groups reflected in Figure 8 and Figure 9. State and non-state stakeholders see time as an element to promote successful organizational engagement as a water consumer, along with stakeholder contributions and proper financial support. The state and non-state groups see, on average, higher levels of dissonance when it comes to alignment regarding the roles of supportive engagement infrastructure, data quality and availability, and neutrality as critical traits of engagement.

Figure 8.

State vs. non-state perceptions on characteristics of engagement (Question 12).

Figure 9.

State and non-state perceptions on successful characteristics of engagement (Question 12).

Reorganizing the data into decision-maker and executive categories shuffles where the group overall average perspectives align. Both groups experience little dissonance regarding how they perceive supportive traits related to finances, human capacity, and data quality and the availability needed for successful engagement. On the other hand, more dissonance is visible between the groups for traits pertaining to time and supportive engagement infrastructure.

Survey respondents indicate a plethora of benefits and costs affiliated with stakeholder engagement and how those benefits/costs impact stakeholder or organizational objectives (Questions 13–15). As for the benefits of stakeholder engagement regarding water objectives, the group response signals that effective actor engagement supports organizational enforcement of rules/regulations and effective policy/reform, as well as increased awareness pertaining to water availability. In addition to the aggregate results, the bifurcated data analysis reveals that all stakeholder groups agree that comprehensive stakeholder collaboration organizationally results in consensus building, ownership, and information exchange. Even though challenges accompany stakeholder collaboration in the water sector, all stakeholders express awareness regarding how their organizations benefit from stakeholders working together. In total, 19% of the respondents mark that resilience is the most important organizational benefit derived from stakeholder engagement and collaboration in the water sector. All stakeholders—non-state/state actors and decision makers/executives—also agree that trust is the second-most important benefit of cross-disciplinary interaction. Linking the benefits of stakeholder collaboration holistically reveals that trust builds resiliency, which culminates into overall sustainability in policy and action; not one benefit is arguably more important than the other because of how intertwined and connected all the benefits listed are that are derived from networking.

Despite the various benefits of water sector stakeholder engagement, stakeholders also detect potential costs or burdens that can result from organizational involvement. In total, 21% of stakeholders identify production and disclosure of information to be a significant burden of their involvement. Even though production and disclosure of specific information emerges as the top cost, the remaining respondent choices selected are insignificant. The little distinction among the selected responses suggests that stakeholders do not significantly perceive the listed costs to be profound, given the similar weight each response carries []. The bifurcated group responses align with the aggregate group responses in the sense that both groups indicate aligning perceptions regarding the production and disclosure of specific information being an organizational cost of involvement.

4. Discussion

The interpretations of the FAOAZ stakeholder perception and engagement survey provide a starting point to guide productive stakeholder conversations regarding water governance and water policy. Conclusions from the survey are based on this one iteration of interpretations, meaning this topic and sector needs further research for more comprehensive understanding purposes.

Frequent stakeholder interactions occur among federal, state, and local water stakeholders. Forums of interaction include informal or formal meetings, WUA/WAA, workshops and trainings, and surveys, polls, and consultations, but the survey findings suggest these platforms are not effective or adequate at promoting cohesion and disseminating information among stakeholders. This conclusion is significant and is arrived at from the volume of stakeholders communicating their unawareness or non-comprehension of the challenges or barriers that other stakeholders face when actively participating in systems designed to enhance water policy and improve water governance. Linking stakeholder perceptions of barrier understanding to the platforms frequently used by stakeholders is paramount, because this gives water stakeholders a tangible opportunity to revamp interactive platforms to promote efficient information dissemination. Restructuring workshops, trainings, meetings, and interactions with WUA/WAA is a realistic action that the government and field offices in Azerbaijan can take to promote organizational goals, transparency, trust, neutrality, and collective cohesion. Furthermore, re-strategizing interactive platforms can breakdown what stakeholders are struggling with or how they are succeeding in collective learning efforts. Overall, such information exchanges can aid decision-making progress, reduce collective burdens or costs (financial and time), aid collaboration, and start the process of modernizing governance systems to address climate change.

The lack of awareness surrounding participation barriers stems not only from historic inherited infrastructure but also from stakeholder proximity to decision making. For example, individuals at an employee level may lack in-depth subject matter knowledge that a more senior leadership role may require. One approach to addressing subject matter discrepancies that relate to water proximity work can occur by creating targeted water training and management certification programs for stakeholders at macro- and micro-levels. Stakeholders may not align in their beliefs regarding public participation and water management qualifications, but enhancing qualifications and learning opportunities for all water stakeholders will benefit the entire sector as a whole.

Missing variables such as funding, data/information, and human or institutional capacity are notable inhibitors or drivers in water governance. The lack of funding emerges as a critical element to water policy development and stakeholder engagement. As equally important to financing is the need for transparency regarding financial use and its end impact. The lack of data and human capacity can serve as barriers to participation, engagement, and success for a myriad of different reasons; however, the root cause of no data and the lack of human resources is more noteworthy in this analysis than how they act as barriers to participation. The reason for this is that missing data and undermined human capacity are a consequence of underfunding and resource misappropriation. Equally significant is that inefficient financing and missing human or institutional infrastructure can be linked to weak governance. Weak governance lacks critical infrastructure, policy, strategy, resources, and processes that allow “public and private actors [to] articulate their interests; frame and prioritize issues; and make, implement, monitor, and enforce decisions” []. Even though stakeholders do not explicitly demarcate weak governance as a force that inhibits progress in the water sector, stakeholders see symptoms that stem from water governance structures. Modernizing governance, therefore, is not a complex process that requires government processes to be completely scratched and reinvented; instead, policies and systems in place need to be updated or injected with new clauses to reflect the new demands of a country aspiring to achieve SDG 6 by 2030 and that is preparing for climate change effects.

Transitioning to a bifurcated stakeholder analysis unveils a variety of nuanced insights traditionally lost in the agglomerate skewed response. However, dissonance in perspectives emerges in the analysis, which requires further study, as this dissonance could be hinting at differences in critical perceptions as they pertain to barriers such as climate change. State and non-state actor perspectives do not align regarding the degree of climate change impacts, despite the general group consensus regarding the threat of climate change.

This insight is vital to note, because future research endeavors or surveys need to further the understanding that surrounds the perceptions of climate change criticality. Understanding the gravity in which stakeholders perceive climate change could be useful to know, because criticality impressions of climate change could hinder or be used to accelerate the installation of modern water policy. Additional state and non-state group input suggests that both groups see the value in increasing agency collaboration, enhancing qualifications of water managers, and increasing data or information availability, given the low levels of dissonance revealed in Figure 6.

At times, non-state actors perceive difficulties that connect with other departmental stakeholders, but state actor perspectives, in comparison, do not align. Misaligned perspectives (high levels of dissonance) also deserve further analysis because of the various unspecified rationales that can be driving how challenges are perceived. At a high-level overview, non-state perceptions hint at roadblocks, arguably encountered by working with the state, especially since perception dissonance exists regarding stakeholders who do not feeling included in decision-making issues regarding water. Although the state and non-state groups view a lot of issues differently, both actor groups see the lack of data, the fragmented government, and the complexity of the issues at play as inhibitors to stakeholder engagement.

Decision-maker (leader) and executive (employee) results also match state/non-state views and the aggregate response, because this group also conveys little to no understanding of the barriers that water users face when it comes to water policy participation. Leader and employee perspectives on water participation barriers align as they pertain to insufficient agency collaboration, inadequate public water education, weak public participation, and inadequate infrastructure. However, more dissonance is evident among decision makers and executives as it pertains to poorly qualified water managers, water receiving low priority in public policy, and fragmented water institutions. The majority of decision makers indicate that water managers are poorly qualified, while their executive counterparts do not indicate the same. Additionally, most of the input from executive stakeholders indicates that they perceive, more than their leaders, that water receives low priority in public policy. This data skew makes deriving further interpretations from this group difficult, but each group’s stance reflects a starting point for future study and further development.

All designated stakeholder groups identify trust and resiliency as the top benefits of cross-disciplinary stakeholder interaction. Cultivating stakeholder trust can lead to the resiliency of water decision making and vice versa, which highlights the interconnectedness of all benefits regarding engagement. Successful stakeholder engagement results in rules and regulatory enforcement; increased awareness pertaining to water availability or other barriers; consensus building; ownership, policy reform, and transparency. The results from successful stakeholder engagement are the same as the benefits yielded from cooperation between organizational stakeholders. Engaged stakeholders, ultimately, create as much impact as organizational stakeholders working together. This insight perpetuates why implementing collaboration or networking strategies needs to be a priority implemented at the highest levels of government to create the expectation for all stakeholders to work together.

Production and disclosure of information is perceived as one cost or burden of organizational involvement by all stakeholder groups. Other than challenges associated with information dissemination, no one cost emerges as a major issue from water sector stakeholder engagement []. Problems in organizational decision making and stakeholder engagement can largely be attributed to poor clarity regarding the expected use of inputs from stakeholders in the decision-making process (i.e., a lack of understanding surrounding expectations) and lack of funding. Both of these issues can be addressed by installing processes that promote systemic transparency.

Even though challenges accompany the dataset, e.g., detracting the weight interpretations in the survey, the following set of recommendations has been designed to help the Azerbaijani government move forward with improving water governance. So far, considerable interventions are needed to enhance water infrastructure, irrigation, transboundary cooperation, sectoral collaboration, and stakeholder engagement, thus addressing all these issues will take comprehensive integrated action. The root causes of both observed gaps and stakeholder perceptions are not the result of one problem but rather of multiple given modern challenges and historic drivers. The overall survey analysis has subsequently generated the following recommendations.

4.1. Legislative Action: Overview

Given the unanimous concern surrounding the anticipated effects of climate change, modern legislation needs to be methodically crafted to adapt to and to mitigate climate change effects. This will require legislation to provide the tools and framework needed for all stakeholders (e.g., farmers, consumers, policymakers, leaders, and government) to holistically and synergistically benefit. Updating legislation can occur through continuous governance analysis, root cause analysis, environmental consultation, and collaboration with third party collaborators, such as the FAO and OECD.

4.2. Legislative Action and Executive (Governmental) Action: Funding

There are three ways that legislation can improve the economic backbone of water policy or governance: (1) policy must play a role in funneling money directly into water initiatives with clear goals and objectives; (2) legislation can increase how efficiently funds are utilized, which involves an element of transparency for all stakeholders to see where the money is going; (3) money needs to be allocated to avenues that indirectly support water policy or initiatives, e.g., education and certification. To summarize, proper funding can help with the following:

- Increase water education measures and awareness for all stakeholders.

- Reduce barriers to participation understanding.

- Strengthen public water understanding and encourage water engagement or ownership.

- Support transparency and foster trust.

- Amplify human or institutional capacity.

- Initiate programs or efforts devoted to data and information collection.

- Pursue modern data collection instrumentation.

- Foster stakeholder connectivity and cooperation.

- Create new platforms for stakeholder, policy maker, farmer, and public interaction.

- Inspire and incentivize political and public interest.

- Bolster enforcement.

- Mitigate the expenses affiliated with logistical and processual expenses.

- Benefit dilapidated water infrastructure and agricultural irrigation systems.

- Build momentum towards climate action and new climate legislation.

- Modernize water user fee infrastructure and payment systems.

- Promote water conservation and drought resiliency.

- Encourage international environmental partnerships.

4.3. Legislative and Executive (Governmental) Action: Policy–Strategy Integration and Implementation

Successfully implementing sustainable water policy requires consistent cross-sectoral collaboration as well as continuous access to reliable data as the climate changes. Future policy needs to be robust enough to mitigate the effects of climate change but also flexible enough to adapt as needed. From what has been derived from the survey so far, creating targeted policies will require the ample prioritization of climate change in public policy (e.g., food, agriculture, and water), as well as financial resources, data, and interdisciplinary coordination across these sectors. Enhancing environmental data monitoring and climate data collection efforts will be imperative to inform necessary policy changes in all sectors, which will require governmental and legislative advocacy to succeed.

4.4. Capacity Development and Education Initiatives

Revamped educational initiatives can promote a thorough understanding of challenges, costs, and benefits that stakeholders encounter whilst working in the water sector. More specifically, educational programs surrounding the fees attached to water use can provide stakeholders with the opportunity to demonstrate budgetary/financial transparency to their counterparts, thus strengthening stakeholder trust. The effects of transparency fostered with stakeholders cascades, i.e., for stakeholders knowing where their money goes promotes trust and subsequent further economic investment, since the security resides in knowing where the money ends up. Additionally, increasing water specific education and training programs can update water manager qualifications; clarify problems that stakeholders face when participating in water policy regarding micro-, meso-, and macro-levels; build capacity; address barriers or conflicting/inhibiting network partnerships.

4.5. Strengthening Stakeholder Engagement: Interagency Coordination

Organizational cooperation and communication within state and non-state entities are not strong enough or systematic enough to build capacity, save time or money, or enhance accountability. Cooperation among stakeholders can be cultivated through the creation or modernization of institutional frameworks, policy revision, and interactive platforms []. Improving interagency coordination can manifest the increase in organizational accountability and ownership of issues that can delay policy progress.

4.6. Strengthening Stakeholder Engagement: Redesigning Stakeholder Engagement Platforms

Stakeholder interaction platforms must be evaluated to determine how to revamp the dissemination of information as it pertains to organizational water programming, strategies, policies, and educational initiatives. Forums need to foster neutrality in meetings or discussions so that all views can be considered or shared. Neutrality cultivates stakeholder trust, ownership, and accountability, promoting more positive engagement and willingness to work together in water decision making.

4.7. Suggestions for Future Work

In addition to recommending the further examination of stakeholder groups for future study, any supplementary research should filter and examine results through additional lenses (categorization). One filter or category that could be used to sort data would specifically examine executive stakeholders in combination with their organizational interest. The goal of this analysis would help better discern whether or not stakeholders near the water sector hold beliefs different from water users located in more removed water user positions. Stakeholder proximity to water is hinted at in this analysis, but limitations of the data inhibit further interpretations of the relationship between these two variables. Another lens that can enrich stakeholder analysis is gender. A gender analysis is not included in this study because of the lack of female respondents who participated in the survey. Future work should compare the perceptions of female versus male participants to see what other information lurks in an aggregate response, as well as questions about gender in various aspects of water governance and management.

Another recommendation is to pre-emptively consider the type of statistical or non-statistical analysis results that are desired from a study. Factoring in the type of analysis that is desired will help determine the size of survey participants needed to obtain more representative results. A more complex multivariable analysis will require more participants and, more importantly, a more representative dataset from which to draw concrete and significant conclusions. At the same time, researchers need to be unafraid to adapt analysis expectations in the event of a poor respondent turnout or unexpected data representation. If pursuing a multivariable statistical analysis, any surveys designed and developed in the future to evaluate similar topics with similar stakeholders should limit the number of free response questions to aid quantification that is needed for statistical analysis. If free response questions are a chosen analytical tool, it is advisable to evaluate the frequency of word use and to depict the qualitative data with word clouds.

A multivariable analysis will require a more intentional survey design to capture where people agree, disagree, or reflect indifference. This design strategy requires the use of questions that utilize ranking systems that reveal degrees of perception. Another strategy on which to capitalize during question design is to build redundancy throughout a survey structure because it can measure dissonance or synchrony in responses. Finally, it is recommended to incorporate, at the beginning, the decision regarding where to house survey data and where to factor data housing into the survey design. Survey data should live in a smart organized living space (database) that can respond with ease to the programmable demands of an investigator. Well-designed databases matter, because the results create sortable data generated with ease via programmable queries, allowing for complex data manipulation, which saves time and effort.

As for future data analysis, a recommended option is running qualitative survey results through an artificial intelligence (AI) text analytics program. Running text through an AI text engine can detect sentiment within text, which is a new method to standardize data collection efforts from interviews and free responses. Determining which sentiments that AI should look for is easily programmable and provides a level of customization to fit researcher needs. An example of sentiments that AI text can scan for are positive or negative statements. A text scanner can then quickly quantify the programmed sentiment by a quick keyword search function, therefore quantifying the sentiment and providing a new layer of agreement or disagreement to evaluate.

Author Contributions

Methodology, A.P.C. and O.Ü.; Formal analysis, C.L.H.; Investigation, C.L.H. and O.Ü.; Data curation, A.P.C.; Writing—original draft, C.L.H.; Writing—review & editing, C.L.H. and O.Ü., A.P.C. and O.Ü.; Visualization, A.P.C.; Supervision, O.Ü. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All of the data and charts used in this analysis can be provided upon request to the authors via email.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the entire field staff at the Azerbaijan Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) office in Baku for their patience, kindness, and enthusiasm for international collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Myre, G. How the Soviet Union’s Collapse Explains the Current Russia-Ukraine Tension. NPR. 2021. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2021/12/24/1066861022/how-the-soviet-unions-collapse-explains-the-current-russia-ukraine-tension (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Gorbachev, Last Soviet Leader, Resigns. The New York Times. U.S. Recognizes Republics Independence. 1992. Available online: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/2021-12/NYT%20front%20page%201991-12-26_1.jpg (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Marques, C.F. Who Saw the Collapse of the USSR Coming? Bloomberg Opinion. 2021. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-12-24/what-caused-the-soviet-union-to-collapse-30-years-ago (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Schmemann, S. The Soviet state, born of a dream, dies. New York Times 1992, 141, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, M.; Stenning, A. East Central Europe and the Former Soviet Union: The Post-Socialist States; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnatsakanian, R. Environmental disaster in Eastern Europe. Le Monde Diplomatique. 2020. Available online: https://mondediplo.com/2000/07/19envidisaster (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Asian Development Bank. Country Environmental Analysis—Azerbaijan; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2005; Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/32178/aze-cea.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Ibrahimov, A. Impact of Post-Soviet Transition on the Economy of Azerbaijan. Geopolitical Info. 2016. Available online: https://www.geopolitica.info/impact-of-post-soviet-transition-the-economy-of-azerbaijan/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Kramer, J.M. Environmental problems in the USSR: The divergence of theory and practice. J. Politics 1974, 36, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmin, J.; Fagan, A. Environmental mobilization and organizations in post-socialist Europe and the former Soviet Union. Environ. Politics 2010, 19, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudwick, N.; Fock, K.; Sedik, D. Land Reform and Farm Restructuring in Transition Countries: The Experience of Bulgaria, Moldova, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8546d4b8-787f-58a1-acfc-c096c29a7606/content (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Langrind, P.M. An overview of environmental law in the USSR (Practicing law and doing business in the Soviet Union). NYLS J. Int. Comp. Law 1990, 11, 483–498. [Google Scholar]

- Law on Amelioration and Irrigation of the Azerbaijan Republic. 1996. Available online: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/aze47602E.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- Kolbasov, O.S. Environmental law administration and policy in the USSR. Pace Environ. Law Rev. 1988, 5, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britannica. Sovkhoz. In Encyclopedia Britannica; Britannica: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/sovkhoz (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Britannica. Kolkhoz. In Encyclopedia Britannica; Britannica: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/kolkhoz (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Petrick, M. Post-Soviet agricultural restructuring: A success story after all? Comp. Econ. Stud. 2021, 63, 623–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mausser, G. Economic Transition Report on Azerbaijan: An Issue of Governance Paper that Studies Issues Facing Azerbaijan’s Economic Transition. International Affairs Forum. 2014. Available online: https://www.ia-forum.org/Search/Results.cfm?Search=Keyword (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Rozengurt, M.A.; Tolmazin, D.H.; Douglas, H. Final Report to National Council for Soviet and East European Research; San Francisco State University: San Francisko, CA, USA, 1989; Available online: https://www.ucis.pitt.edu/nceeer/1989-803-20-2-Rozengurt.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Unver, O. Pan-European Region and the United Nations Economic Commissions for Europe; Academic Lecture Series; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Unver, O. Environmental Issues in Former Soviet Bloc Countries; Academic Lecture Series; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Land Reform Act of 1996. No. 155-IQ. 1996. Available online: https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=2778 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Thomas, M.; Sullivan, S.; Briant, B. Sustainability and development in the former Soviet Union and Central and Eastern European countries. Int. J. Sustain. Hum. Dev. 2013, 1, 163–176. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294892230_Sustainability_and_development_in_the_former_Soviet_Union_and_Central_and_Eastern_European_countries (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Thomas, V.; Orlova, A. Soviet and post-Soviet environmental management: Lessons from a case study on lead pollution. Ambio 2001, 30, 104–111. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4315114 (accessed on 26 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurman, M. Azerbaijan Farm Privatization Project; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Available online: https://web.worldbank.org/archive/website00819C/WEB/PDF/AZERBAIJ.PDF (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Abdullaev, I. Water Management Policies of Central Asian Countries: Integration or Disintegration? International Water Management Institute: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2004; Available online: https://publications.iwmi.org/pdf/H035769.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Amanov, R. Project Report “2022 Stakeholders Survey Report”; TCP/AZE/3801, Improved Water Governance: Towards Sustainable Agricultural Development; FAO-Azerbaijan Office: Baku, Azerbaijan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Khalilov, E. Azerbaijan: Managing Irrigation Systems through Water User Associations; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2019/10/10/azerbaijan-managing-irrigation-systems-through-water-user-associations (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Third National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/67586 (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Ahouissoussi, N.; Neumann, J.E.; Jitendra, S.P. Building Resilience to Climate Change in South Caucasus Agriculture; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/18033/9781464802140.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- International Trade Administration (ITA). Azerbaijan—Country Commercial Guide; ITA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/azerbaijan-agriculture (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Bank. Azerbaijan Country Profile. Climate Knowledge Portal; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/15835-Azerbaijan%20Country%20Profile-WEB.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Lmahamad, A. President Urges Close Analysis of Water Resources in Azerbaijan, including Karabakh. AZERNEWS. 2021. Available online: https://www.azernews.az/nation/177674.html (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- United Nations (UN) Azerbaijan. The United Nations in Azerbaijan. 2022. Available online: https://azerbaijan.un.org/en/about/about-the-un (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- World Bank. Water Users Association Development Support Project; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P107617 (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- World Bank. Bringing Safe, Reliable, and Sustainable Water Supply and Sanitation to Azerbaijan: Azerbaijan’s Second Water Supply and Sanitation Project; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2020/10/15/bringing-safe-reliable-and-sustainable-water-supply-and-sanitation-to-azerbaijan-azerbaijans-second-water-supply-and-sanitation-project (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- United Nations (UN) Water. International Decade for Action ‘Water for Life’ 2005–2015; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA): New York, NY, USA. Available online: https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/water_cooperation_2013/water_convention.shtml (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- United Nations (UN) Economic Commission for Europe. Environmental Performance Reviews: Azerbaijan. 2011. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/env/epr/epr_studies/azerbaijan%20II.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe. OSCE Supports Azerbaijan and Georgia Talks on Shared Water Resources; Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe: Vienna, Austria, 2011; Available online: https://www.osce.org/secretariat/85400 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- European Union Water Initiative+ (EUWI+). Creation of a Water Commission in Azerbaijan a Big Step to Improve Integrated Water Management in the Country. 2021. Available online: https://euwipluseast.eu/en/component/content/article/156-all-activities/activites-azerbaijan/news-of-azerbaijan/798-creation-of-a-water-commission-in-azerbaijan-a-big-step-to-improve-integrated-water-management-in-the-country?Itemid=397 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Akhmouch, A.; Clavreul, D. Stakeholder engagement for inclusive water governance: Practicing what we preach with the OECD water governance initiative. Water 2016, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The Stakeholder Engagement and Perceptions Survey: Water Management for Advanced Agriculture in Azerbaijan; TCP/AZE/3801, Improved Water Governance: Towards Sustainable Agricultural Development; FAO-Azerbaijan Office: Baku, Azerbaijan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The Stakeholder Perceptions and Engagement Survey Methodology; FAO: Baku, Azerbaijan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Unver, O. FAO Azerbaijan Water Stakeholders Survey: Importance of Engaging Stakeholders in Water Governance; TCP/AZE/3801, Improved Water Governance: Towards Sustainable Agricultural Development; FAO-Azerbaijan Office: Baku, Azerbaijan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.H.; Wong, L.H.; Elfithri, R.; Teo, F.Y. A review of stakeholder engagement in integrated river basin management. Water 2022, 14, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Azerbaijan. Third Voluntary National Review of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Submitted to High Level Political Forum (HLPF) of the United Nations. 2021. Available online: https://hlpf.un.org/sites/default/files/vnrs/2021/279452021_VNR_Report_Azerbaijan.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan. European Union Water Initiative National Policy Dialogue Component for Eastern Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia; Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan: Baku, Azerbaijan, 2015. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/AZ_4SC_minutes%20Final.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Ahmadov, E. Water resources management to achieve sustainable development in Azerbaijan. Sustain. Futur. 2020, 2, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.; Camkin, J.; Fenemor, A.; Tan, P.; Baptista, J.M.; Ribeiro, M.; Schulze, R.; Stuart-Hill, S.; Spray, C.; Elfithri, R. OECD Principles on Water Governance in practice: An assessment of existing frameworks in Europe, Asia-Pacific, Africa, and South America. Water Int. 2018, 43, 60–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) and United Nations (UN) Economic Commission for Europe. Water Policy Reforms in Eastern Europe, the Caucuses and Central Asia: Achievements of the European Union Water Initiative; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/env/water/publications/EUWI_EECCA_brochure_2006-2014/EUWI_EECCA_Brochure_2006-2014_EN.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- European Environment Agency. Sharing and Dissemination of Environmental Information Country Maturity Report: Azerbaijan; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020; Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/Azerbaijan%20Country%20Maturity%20Report%20EN.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). OECD Survey: Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Water Policy Group. Global Water Policy Report: Listening to National Water Leaders; Water Policy Group: Sonora, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: http://waterpolicygroup.com/index.php/2021-water-policy-report/ (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Policy Support and Governance Gateway; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/policy-support/governance/en/ (accessed on 30 April 2023).

- Abbasov, R. Project Report “Gap Analysis: Current and Future State of the Water Use in Azerbaijan”; TCP/AZE/3801, Improved Water Governance: Towards Sustainable Agricultural Development; FAO-Azerbaijan Office: Baku, Azerbaijan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).