Investigating the Attitude of Domestic Water Use in Urban and Rural Households in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Do South Africans understand that the country is semi-arid with limited water resources?

- When asked to reduce the amount of water being used, would people know which behavioural changes are more effective than others?

- What makes people use water in the manner that they do, and what will motivate them to change how they use water?

- Are people conscious of the amount of actual water used, and do their perceptions of water use correspond with actual water use?

2. Materials and Methods

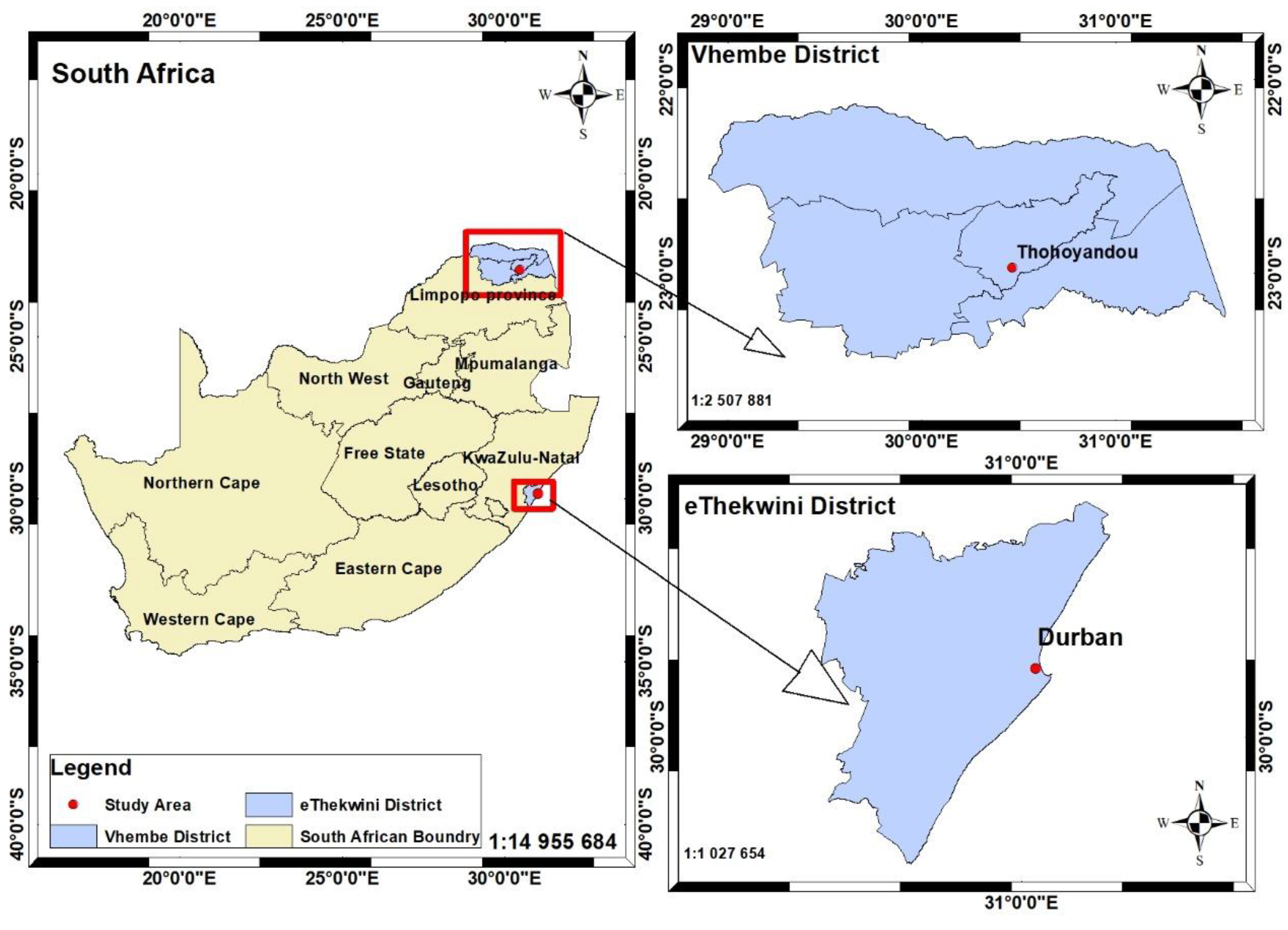

2.1. Location of Study

2.2. Research Approach

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Clearance

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Stage 1

3.2. Stage 2 Experiment

3.3. Water Saver

3.4. Family Upbringing

3.5. Immediate Environment

3.6. Inaccessibility/Scarcity

3.7. Advertisement

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ching, L.; Tay, S.K. Behavioral interventions as policy instruments to manage household water use. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson, M.; Hurlimann, A.; Dolnicar, S. Does water context influence behaviour and attitudes to water conservation? Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibiya, J.E.; Gumbo, J.R. Knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) survey on water, sanitation and hygiene in selected schools in Vhembe District, Limpopo, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 2282–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedden, S.; Cilliers, J. Parched Prospects: The Emerging Water Crisis in South Africa; African Futures Paper 11; Institute for Security Studies: Pretoria, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Otieno, F.A.; Ochieng, G.M. Water management tools as a means of averting a possible water scarcity in South Africa by the year 2025. Water SA 2004, 30, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefike, L.D. The Role of Education in Shaping the Attitudes of Saulspoort Region Communities Towards the Utilisation of Water as an Environmental Resource. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Camp, S. A Guide to Water Saving in South Africa; Department of Water Affairs and Conocer el Grupo y Socializario, Umgeni: Pretoria, South Africa, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Molobela, I.P.; Shinha, P. Management of water resources in South Africa: A review. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 12, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Letsoalo, A.; Blignaut, J.; De Wet, T.; De Wit, M.; Hess, S.; Tol, R.S.; Van Heerden, J. Triple dividends of water consumption charges in South Africa. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 43, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs-Mata, I.M.; De Wet, B.; Banoo, I.; Meissner, R.; De Lange, W.J.; Strydom, W.F. Understanding residential water-use behaviour in urban South Africa. In The Sustainable Water Resource Handbook, South Africa. The Essential Guide to Resource Efficiency in South Africa; Alive2green: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018; Volume 8, pp. 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Vhembe District Municipality. 2011. Available online: http://www.limdlgh.gov.za/documents/idp/Vhembe%202011%2012%20IDPs/VHEMBE%20DISTRICT%202011%2012%20IDP%20REVIEW%2026%2003%202011.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2019).

- Department of Health South Africa. 2011. Available online: http://www.hst.org.za/publications/NonHST%20Publications/Limpopo%20-%20Vhembe%20District.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Aaron, J.; Muellbauer, J.; Prinsloo, J. Estimates of household sector wealth for South Africa, 1970–2003. Rev. Income Wealth 2006, 52, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nekhavhambe, T.J.; Van Ree, T.; Fatoki, O.S. Determination and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in rivers, surface runoff, and sediments in and around Thohoyandou, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Water SA 2014, 40, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Census: Concepts and Definitions; Report No. 03-02-26; Stats SA Library Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) Data: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Purdon, A.; Mulholland, M.; Buckley, C.A.; Brouckaert, C.J. Durban water distribution network optimisation. South Africa by the year 2025. In Proceedings of the WISA 2010 Conference (Water Institute of South Africa), Durban, South Africa, 18–22 April 2010; Volume 30, pp. 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Wadoux, A.M.C.; Brus, D.J.; Heuvelink, G.B. Sampling design optimisation for soil mapping with random forest. Geoderma 2019, 355, 113913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, S.N.K. A Review of “Observation Techniques: Structured to Unstructured”; Gillham, B., Ed.; Continuum International Publishing Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 112, pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Raosoft, I. Sample Size Calculator by Raosoft, Inc. 2020. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, N. City of Cape Town Residential Water Consumption Trend Analysis; Department of Environmental and Geographical Sciences, University of City of Cape Town: Western Cape, South Africa, 2015; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Graymore, M.L.; Wallis, A.M. Water savings or water efficiency? Water-use attitudes and behaviour in rural and regional areas. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2010, 17, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanayak, S.K.; Yang, J.C.; Whittington, D.; Bal Kumar, K.C. Coping with unreliable public water supplies: Averting expenditures by households in Kathmandu, Nepal. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglia, M.; Cook, S.; Tapsuwan, S. Promoting water conservation: Where to from here? Water 2018, 10, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E.E. Parenting and its effects on children: On reading and misreading behavior genetics. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellen, I.G.; Turner, M.A. Does neighborhood matter? Assessing recent evidence. Hous. Policy Debate 1997, 8, 833–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.L.; Brumand, J. Paradoxes in landscape management and water conservation: Examining neighbourhood norms and institutional forces. Cities Environ. 2014, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Qin, W. Public perception of water consumption and its effects on water conservation behavior. Water 2014, 6, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.K.; Saha, M.; Takada, H.; Bhattacharya, A.; Mishra, P.; Bhattacharya, B. Water quality management in the lower stretch of the river Ganges, east coast of India: An approach to environmental education. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1559–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieswiadomy, M.L. Estimating urban residential water demand: Effects of price structure, conservation, and 37 education. Water Resour. Res. 1992, 28, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Households | Total Number in Household | Male | Female | Number of Children | Head of Household | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | |

| 1 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | Grandmother | Father |

| 2 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | Grandmother | Grandfather |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | Grandfather | Father |

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Mother | Aunty |

| 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | Mother | Father |

| 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | Father | Father |

| 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | Grandmother | Mother |

| 8 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Mother | Mother |

| 9 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Grandmother | Grandmother |

| 10 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | Father | Mother |

| Residents Living in the Rural Community | Residents Living in the Urban Community | Significant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 44 | 43.1 | 55 | 43.3 | 0.980 |

| Female | 58 | 56.9 | 72 | 56.7 | |

| Total | 102 | 100 | 127 | 100 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 16–20 | 26 | 25.5 | 50 | 39.4 | 0.513 |

| 21–30 | 45 | 44.1 | 26 | 20.5 | |

| 31–40 | 9 | 8.8 | 29 | 22.8 | |

| 41–50 | 13 | 12.7 | 14 | 11 | |

| 51 and above | 9 | 8.8 | 8 | 6.3 | |

| Total | 102 | 100 | 127 | 100 | |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| No level of education | - | - | 5 | 3.9 | 0.001 |

| Primary | 35 | 34.3 | 22 | 17.3 | |

| Secondary | 48 | 47.1 | 31 | 24.4 | |

| Tertiary | 18 | 17.6 | 69 | 53.3 | |

| Did not tell | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| Total | 102 | 100 | 127 | 100 | |

| How long have you lived in the community (years) | |||||

| Less than 1 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 10.2 | 0.001 |

| 1–5 | 3 | 2.9 | 23 | 18.1 | |

| 6–10 | 16 | 15.7 | 25 | 19.7 | |

| 11–15 | 20 | 19.6 | 33 | 26 | |

| Above 15 | 59 | 57.8 | 33 | 26 | |

| Did not tell | 2 | 2 | - | - | |

| Total | 102 | 100 | 127 | 100 | |

| Residents Living in the Rural Community | Residents Living in the Urban Community | Significant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Do you feel you and your household are water savers? | |||||

| Strongly agree | 85 | 83.3 | 46 | 36.2 | 0.001 |

| Agree | 4 | 3.9 | 17 | 13.4 | |

| Maybe | - | - | - | - | |

| Disagree | 13 | 12.7 | 23 | 18.1 | |

| Strongly disagree | - | - | 41 | 32.3 | |

| Total | 102 | 100 | 127 | 100 | |

| Do you think your family upbringing influences your use of water? | |||||

| Strongly Agree | 76 | 74.5 | 72 | 56.7 | 0.001 |

| Agree | 10 | 9.8 | - | - | |

| Maybe | 3 | 2.9 | 16 | 12.3 | |

| Disagree | 13 | 12.7 | 22 | 17.3 | |

| Strongly disagree | - | - | 17 | 13.4 | |

| Total | 102 | 100 | 127 | 100 | |

| Have you seen any form of awareness of water scarcity before? | |||||

| Seen | 24 | 23.5 | 97 | 76.4 | 0.001 |

| Maybe | 4 | 3.9 | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Not seen | 72 | 70.6 | 27 | 21.3 | |

| Did not tell | 2 | 2 | - | - | |

| Total | 102 | 100 | 127 | 100 | |

| Does your immediate environment influence your use of water? | |||||

| Strongly agree | 76 | 74.5 | 101 | 79.5 | 0.911 |

| Agree | 5 | 4.9 | - | - | |

| Maybe | - | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Disagree | 18 | 17.6 | 11 | 8.7 | |

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 2.9 | 14 | 11 | |

| Total | 102 | 100 | 127 | 100 | |

| Is there water inaccessibility or scarcity in your community? | |||||

| Strongly agree | 85 | 83.3 | 10 | 7.9 | 0.001 |

| Agree | - | - | 18 | 14.2 | |

| Maybe | - | - | - | - | |

| Disagree | 14 | 13.7 | - | - | |

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 2.9 | 99 | 78 | |

| Total | 102 | 100 | 127 | 100 | |

| Spearman’s Rho | Have You Seen or Heard Any Form of Awareness on Water Scarcity before | Correlation Coefficient | 1.000 | 0.306 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | |||

| N | 229 | 229 | ||

| Water Saver | Correlation Coefficient | 0.306 ** | 1.000 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | |||

| N | 229 | 229 |

| Spearman’s rho | Water Saver | Correlation Coefficient | 1.000 | 0.342 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | |||

| N | 229 | 229 | ||

| Inaccessibility/Scarcity | Correlation Coefficient | 0.342 ** | 1.000 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | |||

| N | 229 | 229 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Njoku, P.O.; Durowoju, O.S.; Uhunamure, S.E.; Makungo, R. Investigating the Attitude of Domestic Water Use in Urban and Rural Households in South Africa. Water 2022, 14, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14020210

Njoku PO, Durowoju OS, Uhunamure SE, Makungo R. Investigating the Attitude of Domestic Water Use in Urban and Rural Households in South Africa. Water. 2022; 14(2):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14020210

Chicago/Turabian StyleNjoku, Prince Obinna, Olatunde Samod Durowoju, Solomon Eghosa Uhunamure, and Rachel Makungo. 2022. "Investigating the Attitude of Domestic Water Use in Urban and Rural Households in South Africa" Water 14, no. 2: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14020210

APA StyleNjoku, P. O., Durowoju, O. S., Uhunamure, S. E., & Makungo, R. (2022). Investigating the Attitude of Domestic Water Use in Urban and Rural Households in South Africa. Water, 14(2), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14020210