Travelling Plastics: Exploring River Cruise Companies’ Practices and Policies for the Environmental Protection of the Rhine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

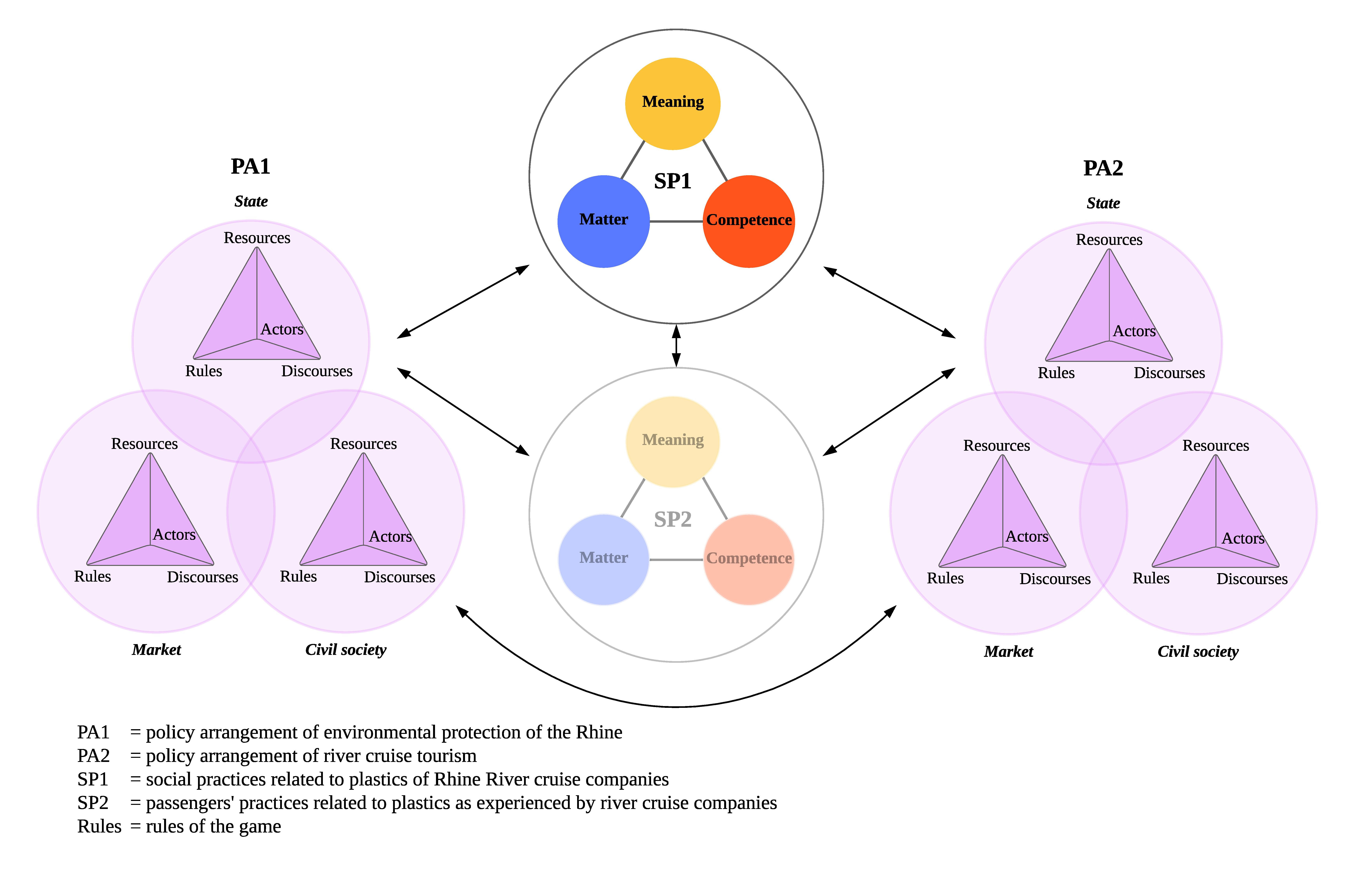

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Conceptualisation of the Policy Context

2.2. Operationalisation of Theoretical Concepts Used

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Policy Domains of Rhine Environmental Protection and River Cruise Tourism

4.1.1. Rules of the Game

| Rules of the Game for River Cruise Tourism | Focus |

|---|---|

| Treaty of Lisbon (2009) | The legal basis provided for the river cruise sector by the European Union. Enhance member state’s collaboration (interchanging best practices). Promote competitiveness of the EU’s undertakings in the river cruise sector. EU supported shaping of a favourable environment in which the tourism sector flourishes. |

| Europe, the world’s No 1 tourist destination—a new political framework for tourism in Europe (2010) | Sustainable tourism, improvement of competing efforts, the perceptibility of tourist destination Europe, and the expansion of financial policies. The aim of the memorandum was to remain the world’s number one tourist destination. |

| Green Award | Requirements for inland shipping sector to promote environmentally friendly navigation. Inland shipping certificate used for river cruise vessels since 2017. Award levels: bronze, silver and gold (based on a point system). Green Award focuses on emission reductions. Green Award concentrates on waste separation [requirement 40a and 40b]. There are no specific requirements concerning plastic use onboard. Operating a ship with a wastewater treatment plant is a prerequisite [requirement 50g]. One requirement focuses on river cruises, specifically hotel facilities [requirement 70d]. |

| Convention on the collection, deposit and reception of waste generated during navigation on the Rhine and other inland waterways (CDNI) | Objective: “reaching an ever more environmentally friendly inland navigation sector” [41]. Category c includes household waste and wastewater from passenger ships [42]. CDNI does not specify which actor is accountable for financing the construction of infrastructure for wastewater and sludge [43]. Article 77 of the CDNI shows that wastewater discharge in rivers is allowed from vessels with a capacity of fewer than 50 passengers. Since 2011, vessels with a capacity of more than 50 passengers are only allowed to discharge wastewater when using a treatment plant onboard which follows ES-TRIN regulations. |

| ES-TRIN 2021 | Provisions regarding shipbuilding and equipment by the EU committee for drawing up standards in the field of inland navigation (CESNI). Includes technical standards for onboard sewage treatment plants. Guidelines outlined by the European Commission (DG MOVE) and the Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine (CCNR). |

Rules of the Game Dynamics of Interaction

4.1.2. Discourses PA1 Environmental Protection of the Rhine

PA2 River Cruise Tourism

Discourses Dynamics of Interaction

4.2. River Cruise Companies’ Practices Related to Plastics

4.2.1. Matter

Plastic Products Provided on Board

“A few years ago, we already chose to ban single-use plastics; then we switched from plastic straws to paper straws. Besides, we focus on banishing [plastic] packaging materials. We are in conversation with subcontractors of suppliers so that [where it is possible] we have [plastic] packaging converted to paper packaging.”(case interview 6)

Onboard Waste Facilities

Waste Facilities Onshore

“Onboard the other vessel we have a wastewater tank, and the wastewater is disposed at places where it is possible. And if this is not possible, and the tank is full, wastewater is discharged into the river environment.”(case interview 2)

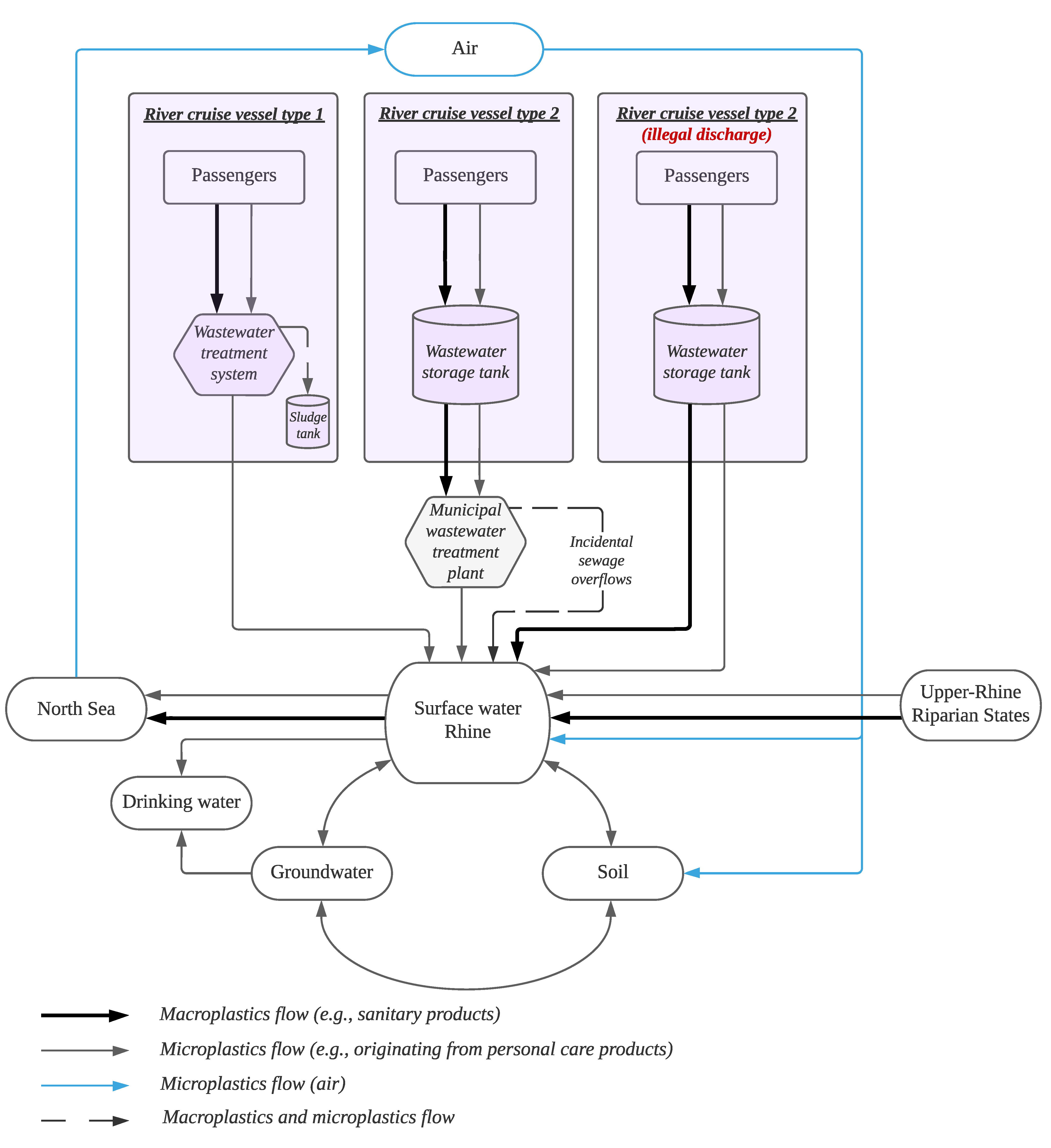

Wastewater Treatment

- A wastewater treatment plant onboard has a capacity of approximately 15 cubic meters (comparable to the size of one cabin) [43].

- After four to five weeks, type 1 vessels have to empty their sludge tank onshore (average sludge tank capacity: 10 cubic meters).

- Annually, about five new river cruise vessels with a wastewater treatment plant are constructed in Europe (personal communication 6).

- When constructing new vessels, river cruise companies are obliged to install a wastewater treatment plant on board following ES-TRIN regulations (personal communication 6).

- A wastewater storage tank onboard has an average capacity of 20 cubic meters (case interview 3).

- Every two to three days, type 2 vessels have to empty their wastewater storage tank (cases 1–4).

- It is estimated that around 350 European river cruise vessels still have a wastewater storage tank onboard (personal communication 6).

4.2.2. Competences

“[A working group at the European River Cruise Association level], that is something that is missing. (…) I mean, we [as a river cruise company] have shared our knowledge and findings always, but if it has been taken up as such [by other companies]. I do not know.”(expert interview 8)

Passenger’s Sanitary Waste Disposal Skills

4.2.3. Meaning

“That was a choice, we did not want to put a bin in the rooms where the waste will be separated in this way because we are in the five-class service segment after all, and we sell a luxury product, so we have chosen to not separate waste in passengers’ rooms.”(case interview 6)

- Green Award sets codes of conduct for an onboard wastewater treatment plant.

- Vessels with a wastewater storage tank on board are not eligible for this certificate (case interview 1.3).

- Expectedly by 2023, only vessels with a Green Award will be allowed in large harbours like Amsterdam (case interview 1.3), constraining type 2 vessels (Figure 2) the access to vital wastewater reception facilities.

- Within the river cruise sector, there is a demand for clear future requirements regarding wastewater treatment plants because at this moment it is not guaranteed that a plant installed in 2021 will still be approved in 15-or 20-years’ time (case interview 2).

- For newbuild river cruise vessels, the investment costs for a wastewater treatment plant are between 400,000 and 500,000 euros (case interview 2).

- Because of adaptations to the vessels’ casco, the investments for a wastewater treatment plant onboard type 2 vessels are about 200,000 to 300,000 euros extra compared to newbuild vessels (case interview 7). These expenses hinder type 2 cruise companies to shift to a purification plant (case interviews 2 & 7).

- The ‘greening’ discourse identified in PA2 is also linked to the Green Award.

4.2.4. Concluding Remarks on Plastic Practices Onboard

4.3. The Influence of Governance on Practices

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Policy and Practical Recommendations

5.2.1. Recommendation for the European Commission

European Directive on Plastics in the Freshwater Environment

5.2.2. Recommendations for River Committees and CDNI

Action Programme on Plastics

Establishing a Dense Network of Waste Reception Facilities along the Rhine River

5.2.3. Recommendations for the River Cruise Sector

Connecting the Ooze Luxury Discourse to Passengers’ Waste Separation

Preventing Plastic Pollution on the Outside Deck

Raising Awareness about Plastic Emissions via Bathroom Sinks and Toilets

5.2.4. Recommendations for a Transition to Sustainable Waste(Water) Management

Inclusion of Plastics in the Green Award and ES-TRIN Regulations

5.3. Recommendations for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number | Document | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) | River environment |

| 2 | Dutch River Basin Management Plan Rhine 2016–2021 | Rhine river environment |

| 3 | ICPR Rhine 2020 programme | Rhine river environment |

| 4 | ICPR Rhine 2040 programme | Rhine river environment |

| 5 | Marine Strategy Framework Directive (2008/56/EC) | Marine environment |

| 6 | Single-Use Plastics Directive (2019/904/EU) | Reducing the impact of plastics on the environment |

| 7 | CDNI Consolidated Convention (January 2019) | Waste generated during navigation on Rhine and inland waterways |

| 8 | Water Management Act | Integral water management |

| 9 | Treaty of Lisbon | Legal basis tourism |

| 10 | Europe, the world’s No 1 tourist destination—a new political framework for tourism in Europe | Tourism |

| 11 | 2030 Perspective: Destination Netherlands (2018) | Tourism |

| 12 | Green Award programme of requirements (January 2018) | Sea shipping and inland shipping |

| 13 | ES-TRIN (2021) | Inland shipping (technical standards) |

Appendix B

| Interview | Function Respondent | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Advisor Ecology and Water Quality at Rijkswaterstaat | 15 April 2021 |

| 2 | Policy officer Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine | 22 April 2021 |

| 3 | Researcher plastic monitoring at Wageningen University & Research | 10 May 2021 |

| 4 | Multi-level water governance expert at Utrecht University | 18 May 2021 |

| 5 | Advisor Waste and Circularity at Rijkswaterstaat | 21 May 2021 |

| 6 | Researcher plastic monitoring at Radboud University | 25 May 2021 |

| 7 | Advisor Water Quality and International Coordination at Rijkswaterstaat | 28 May 2021 |

| 8 | Vice-president European River Cruise Association | 1 June 2021 |

| 9 | Advisor Waste and Behaviour at Rijkswaterstaat | 8 July 2021 |

| Personal Communication | Date | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | An organisation supplying wastewater treatment systems for inland navigation vessels | 16 August 2021 |

| 2 | A company supplying wastewater treatment systems onboard river cruise vessels | 9 August 2021 |

| 3 | Rijkswaterstaat advisor in Enforcement | 10 June 2021 |

| 4 | Rijkswaterstaat Advisor in Traffic and Water Management | 9 June 2021 |

| 5 | Harbour master at the port of Arnhem and Nijmegen | 8 July 2021 |

| 6 | An organisation supplying wastewater treatment systems for inland navigation vessels | 24 August 2021 16 March 2022 |

References

- Van Emmerik, T.; Schwarz, A. Plastic debris in rivers. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2020, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Derraik, J.G. The pollution of the marine environment by plastic debris: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Moore, C.J.; Vom Saal, F.S.; Swan, S.H. Plastics, the environment and human health: Current consensus and future trends. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2153–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blettler, M.C.; Abrial, E.; Khan, F.R.; Sivri, N.; Espinola, L.A. Freshwater plastic pollution: Recognizing research biases and identifying knowledge gaps. Water Res. 2018, 143, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van der Wal, M.; van der Meulen, M.; Tweehuijsen, G.; Peterlin, M.; Palatinus, A.; Kovac Viršek, M. SFRA0025: Identification and Assessment of Riverine Input of (Marine) Litter; Final Report for the European Commission DG Environment; Report No.: ENV.D.2/FRA/2012/0025; Eunomia Research & Consulting Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, S.; Worch, E.; Knepper, T.P. Occurrence and spatial distribution of microplastics in river shore sediments of the Rhine-Main area in Germany. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 6070–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, T.; Hauk, A.; Walter, U.; Burkhardt-Holm, P. Microplastics profile along the Rhine River. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, H.; Brandsma, S.; Van Velzen, M.; Vethaak, A. Microplastics en route: Field measurements in the Dutch river delta and Amsterdam canals, wastewater treatment plants, North Sea sediments and biota. Environ. Int. 2017, 101, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebreton, L.; Egger, M.; Slat, B. A global mass budget for positively buoyant macroplastic debris in the ocean. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12922. [Google Scholar]

- Lebreton, L.C.; Van Der Zwet, J.; Damsteeg, J.-W.; Slat, B.; Andrady, A.; Reisser, J. River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Board, M. Clean Ships, Clean Ports, Clean Oceans: Controlling Garbage and Plastic Wastes at Sea; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, A.; Verboom, E.; Van en Kieboon, M. Analyse Bronaanpak Schone Rivieroevers [Internet]. 2019, pp. 1–24. Available online: https://zwerfafval.rijkswaterstaat.nl/areaal/rivieren/bronaanpak-plastic-zwerfafval/@223619/analyse-bronaanpak-schone-rivieroevers/ (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Butt, N. The impact of cruise ship generated waste on home ports and ports of call: A study of Southampton. Mar. Policy 2007, 31, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCNR. Annual Report 2020 Inland Navigation in Europe: Market Observation; CCNR: Strasbourg, France, 2020; Available online: https://inland-navigation-market.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/CCNR_annual_report_EN_2020_BD.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Sanches, V.L.; Aguiar, M.R.D.C.M.; de Freitas, M.A.V.; Pacheco, E.B.A.V. Management of cruise ship-generated solid waste: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 151, 110785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, B.; van Tatenhove, J.; Leroy, P. Policy arrangements. In Political Modernisation and the Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, B.; Leroy, P.; van Tatenhove, J. Political modernisation and policy arrangements: A framework for understanding environmental policy change. Public Organ. Rev. 2006, 6, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzki, T.R. Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki, T.R. The Site of the Social: A Philosophical Account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change; Penn State Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Logic of Practice; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Reckwitz, A. Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2002, 5, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southerton, D.; Chappells, H.; Van Vliet, B. Sustainable Consumption: The Implications of Changing Infrastructures of Provision; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Liefferink, D. The dynamics of policy arrangements: Turning round the tetrahedron. In Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Arnouts, R.; Van der Zouwen, M.; Arts, B. Analysing governance modes and shifts—Governance arrangements in Dutch nature policy. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 16, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steurer, R. Disentangling governance: A synoptic view of regulation by government, business and civil society. Policy Sci. 2013, 46, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenau, J.N.; Czempiel, E.-O.; Smith, S. Governance without Government: Order and Change in World Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Driessen, P.P.; Dieperink, C.; Van Laerhoven, F.; Runhaar, H.A.; Vermeulen, W.J. Towards a conceptual framework for the study of shifts in modes of environmental governance–experiences from the Netherlands. Environ. Policy Gov. 2012, 22, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soiferman, L.K. Compare and Contrast Inductive and Deductive Research Approaches; Online Submission Manitoba; University of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, D.; Torfing, J. Discourse Theory in European Politics: Identity, Policy and Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van Klink, D. River Cruise Tourism and the Environmental Protection of the Rhine: Exploring Policy Arrangements and River Cruise Companies’ Practices Related to Plastics. Master’s Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst, R. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. In Key Methods in Geography; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- De Massis, A.; Kotlar, J. The case study method in family business research: Guidelines for qualitative scholarship. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, B.F.; Miller, W.F. A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In Doing Qualitative Research; Crabtree, B.F., Miller, W.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K.; Smith, J. Grounded theory. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; Smith, J.A., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 81–110. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Holton, J. Staying open: The use of theoretical codes in grounded theory. Grounded Theory Rev. 2005, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Van Thiel, S. Research Methods in Public Administration and Public Management: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eerd, M. Back to Brussels-Reloading Implementation Experiences in Multi-Level EU Water Governance. Ph.D. Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CDNI. The CDNI: For an Ever More Environmentally Friendly Inland Navigation Sector! [Internet]. n.d. Available online: https://www.cdni-iwt.org/?lang=en (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Rijkswaterstaat. Deel C: Overig Scheepsbedrijfsafval [Internet]. n.d. Available online: https://www.rijkswaterstaat.nl/water/wetten-regels-en-vergunningen/scheepvaart/scheepsafvalstoffenverdrag/deel-c-overig-scheepsbedrijfsafval (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Vermij, H.; De Vries, K. Effectrapportage Uitbreiding Lozingsverbod Passagiersschepen; Report No.: BG4021MARP2012110902; Royal HaskoningDHV: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Summer Session 2021 of the Contracting Parties Conferences. [Press Release]. Strasbourg: CDNI2021 June 22. Summer Session 2021 of the Contracting Parties Conference. 2021 June 22; Strasbourg. Available online: https://www.cdni-iwt.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/cpccp21_03en.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Derksen, A.; Roex, E. Microverontreinigingen in Oppervlaktewater Verdienen Aandacht. H2O Online [Internet]. 2015, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.h2owaternetwerk.nl/vakartikelen/microverontreinigingen-in-oppervlaktewater-verdienen-aandacht (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Derksen, A. Microverontreiniging in Het Water. Een Overzicht; STOWA: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- The Travel Foundation. Environmental Sustainability for River Cruising: A Guide to Best Practices. 2013, pp. 1–60. Available online: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/travelfoundation/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/12153327/Environmental_Sustainablity_for_River_Cruising_v1.0.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Bänsch-Baltruschat, B.; Brennholt, N.; Kochleus, C.; Reifferscheid, G. Conference on Plastics in Freshwater Environments; Umwelt Bundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

| Case | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fleet | Dutch | Dutch | Dutch | Dutch | Dutch | Swiss German | Swiss | American | American English German |

| Number of stars | 3–4 | 3–4 | 3–4 | 3–4 | 3–4 | 3–4 | 4–5 | 4–5 | 4–5 |

| Number of active vessels | 1 * | 1 * | 3 * | 3 * | 4 * | 55 */66 | 19 */35 | 5 */19 | 28 * |

| Function respondent | Ship owner & captain | Ship owner & captain | Ship owner & captain | Nautical Technical Manager | Nautical Technical Manager | Nautical Manager | Nautical Director | Nautical Director | Nautical Manager |

| Guided tour on board | Fieldwork | Fieldwork | Fieldwork | Fieldwork | Fieldwork | Fieldwork | |||

| Date | 3 May 2021 | 7 May 2021 | 7 June 2021 | 8 June 2021 | 11 May 2021 | 24 May 2021 | 20 May 2021 | 27 May 2021 | 11 June 2021 |

| Social Practice Theory | Subjects Incorporated in the Interview Guide |

|---|---|

| Matter | Products: single-use plastic products, water bottles, personal care products, tableware, cigarettes, sanitary waste. Packaging: individual packaging, large-size packaging. Waste infrastructure: waste bin, sanitary waste bin, waste sign, waste separation bin, open/closed waste bins at the deck, waste depot onboard vessel, onshore waste containers, wastewater storage tank, wastewater treatment system, wastewater reception facilities, sludge reception facilities. Information provision: icons, pictograms and/or text used explaining waste management. |

| Competence | Knowledge of waste separation, passenger instructions, crew members waste management skills, river cruise companies’ plastic waste reduction skills. |

| Meaning | Conceptions of waste, idea of comfort and luxury, symbolic meaning of waste signs, plastic reduction objectives, importance of waste separation, value of sustainable waste management, awareness of the impact of plastics on the environment. |

| Rules of the Game for Rhine Environmental Protection | Focus |

|---|---|

| Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) | Inclusive water protection in Europe’s river districts, coastal waters, and groundwater. Objective: reaching a ‘good chemical and ecological status’. Diminishing 45 priority substances in the freshwater environment. Plastics is not included in the priority substances list. |

| Marine Strategy Framework Directive (2008/56/EC) | Safeguarding European marine environments. Recent focus on scrutinising data on plastics originating from inland water areas. Source-based approach: prevent plastics from entering the North Sea. |

| Single-Use Plastics Directive (2019/904/EU) | Focus on the effect of plastic items on people’s health and the marine environment. 10 Most frequently encountered plastic items on beaches were categorised. Restricts single-use plastic items from entering the market (e.g., cotton swabs and straws). |

| ICPR Rhine 2040 programme | Focus on water quality, high and low water levels, and ecology. Goal six of the Rhine 2040: diminishing the (plastic) waste influx in the aquatic environment (source-based approach). Measurements: creating awareness through a waste collection campaign, collecting data on waste management, and improving waste management. The International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) has not yet decided whether they will set up an expert group plastic (expert interview 5). |

| Waste Stream | Amount of Waste in Litres |

|---|---|

| Plastic | 50,000 |

| Paper | 100,000 |

| Glass | 40,000 |

| Biomaterial | 40,000 |

| Metal | 15,000 |

| Chemical | 5000 |

| Residual | 150,000 |

| Total | 400,000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Klink, D.; Wiering, M.; van Eerd, M.; Schoor, M. Travelling Plastics: Exploring River Cruise Companies’ Practices and Policies for the Environmental Protection of the Rhine. Water 2022, 14, 1978. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14121978

van Klink D, Wiering M, van Eerd M, Schoor M. Travelling Plastics: Exploring River Cruise Companies’ Practices and Policies for the Environmental Protection of the Rhine. Water. 2022; 14(12):1978. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14121978

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Klink, Demi, Mark Wiering, Marjolein van Eerd, and Margriet Schoor. 2022. "Travelling Plastics: Exploring River Cruise Companies’ Practices and Policies for the Environmental Protection of the Rhine" Water 14, no. 12: 1978. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14121978

APA Stylevan Klink, D., Wiering, M., van Eerd, M., & Schoor, M. (2022). Travelling Plastics: Exploring River Cruise Companies’ Practices and Policies for the Environmental Protection of the Rhine. Water, 14(12), 1978. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14121978