Abstract

Weather and climate have been participating in an imperative function in both the expansion and crumple of mankind civilizations diagonally across the globe ever since the prehistoric eras. The Neolithic Mehrgarh (ca. 7000–2500 BC) and Balochistan and Indus Valley civilizations (ca. 2500–1500 BC), in Sindh Province in Pakistan, have been the spotlight of explorations to historians, anthropologists, and archeologists in terms of their origin, development, and collapse. However, very rare consideration has been given previously to the role of weather and climate, sanitation, and wastewater technologies in highlighting the lessons of these formerly well-developed ancient metropolitan civilizations. This study presents an existing climate of the archaeological sites, sanitation, and wastewater technologies to recognize the different elements that influenced the evolution of the civilization mystery. In addition, it is recommended that the weather and climate conditions in southwest Asia were the foremost controlling element in resolving the destiny of the Indus and Mehrgarh civilizations. Furthermore, the rural tradition was mostly adapted by the increasing rate of western depressions (winter rains), as well as monsoon precipitation in the region. The factors that affected the climate of both civilizations with the passage of time might be population growth, resource conflicts, technological advancement, industrial revolution, Aryan invasion, deforestation, migration, disasters, and sociocultural advancement. The communities residing in both civilizations had well developed agriculture, sanitation, water management, wells, baths, toilets, dockyards, and waterlogging systems and were the master of the water art.

1. Introduction

Historically, people have recognized less concerning evolution in the Neolithic Mehrgarh (ca. 7000–2500 BC) and Indus Valley (ca. 2500–1500 BC) than about those located in the Middle East, Central Asia, and Europe. Historians have not yet decoded the Mehrgarh and Indus Valley scheme of the script, hydrology, trade and commerce, politics and security, etc. Evidence comes largely from archaeological excavations. However, many archaeological artifacts remain unexcavated, and were washed by both floods and desert storms many years ago. At its peak era, though, the Indus Valley and Mehrgarh civilizations covered a vast area compared to other civilizations of the time. Nobody knows for sure how human civilization originated in the Indus Valley and Mehrgarh; however, it is expected that the first human (Hazrat Adam) landed in Sari Lanka and his nation started to spread toward the north (Indus Valley). The northern nomads may have initiated their approach all the way through the Khyber Valley, Hindu Kush ranges (Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Pakistan), and flourished another civilization named Gandhara, which was located over a vast region of Afghanistan, Central Asia, Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Pakistan, and Nepal, as well as up to the eastern Asian coast, Japan, and North and South Korea [1]. Some of the evidence, such as scripts, ornaments, statues, dresses, burials, weapons, industry, artifacts, coins, and house constructions of Gandhara civilization, also match archaeological remains in Canada, United States, and the northern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, especially Germany, Italy, Macedonia, Greece, and England.

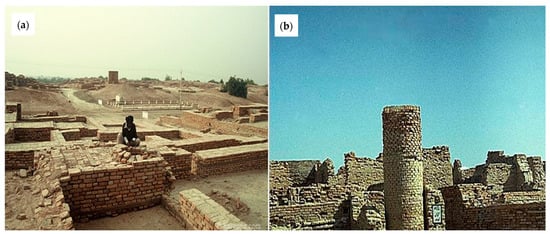

Around ca. 2500 BC, while the Egyptians and Minoans were constructing pyramids and palaces, the residents of the Indus civilization made burnt mud bricks for Pakistan’s earliest urban centers of Mehrgarh, Moen-Jo-Daro, Harappa, and Kot Diji. They built sturdy embankments to sustain wastewater out of their towns and assembled manmade land masses to elevate constructed areas above the water catastrophe level. Archaeologists have excavated more than 100 archaeological sites along the Indus River and its major sub-rivers in Pakistan, in which the major urban areas are Moen-Jo-Daro, Kalibangan, Dholavira, Harappa, Kot Dijji, and Lothal [2].

The most notable accomplishments of the people in the Indus Valley and Mehrgarh civilizations is their advanced urban planning. The inhabitants of the Indus Valley constructed their towns according to a specific grid scheme. The towns had a walled area known as a sanctuary, which included the main well flourished houses of the urban areas. The houses were risen on burnt mud bricks of ordinary dimensions [3].

The advanced plumbing and sewer systems were also developed by early engineers, which could equal any city drainage scheme constructed earlier than the nineteenth century. The consistency in the planning and building of cities indicates that the Indus residents established a powerful central government system [4]. The civilization of Indus Valley is assumed to have belonged to the Copper Stone Age, because the occurrence of iron implements has not thus far been identified in any other ancient civilization across the world [5].

The Neolithic Mehrgarh (ca. 7000–2500 BC) in Balochistan and Indus Valley civilizations (ca. 2500–1500 BC), in Sindh Province in Pakistan, have been the spotlight of explorations to historians, anthropologists, and archeologists in terms of their origin, development, and collapse. However, very rare consideration has previously been given to the role of weather and climate or water and wastewater technologies in highlighting the lessons of these formerly well-developed ancient metropolitan civilizations. This study presents the existing climate of the archaeological sites, sanitation, and hydro-technologies to recognize the different elements that influenced the evolution of the civilization mystery.

2. Study Area and Methodology

Generally, the Indus civilization region was habitual to the five prevalent Ancient urban civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Minoan, South Asia, and Qin Chinese, with a geographical vicinity of approximately 100,000 km2 [6]. The Indus Valley civilization covered the Himalaya mountains (North), the Arabian Sea (South), the Rajasthan desert (East), and the Kirthar mountains of Baluchistan in the West [7].

Presently, the climate of the Indus civilization sites fall into arid continental climate, with warm short winters (Figure 1) and hot long summers (Pakistan), and a coastal climate in Lothal and Dholavira (India). This study explains the weather, climate, and wastewater and sanitation technologies of the Mehrgarh and Indus Valley civilizations, Pakistan, that flourished over the entire area from ca. 7000 to 1500 BC. This work mainly depended on field visits to the sites, discussions with the stakeholders, and a literature review. Some of the information about the Mehrgarh and Indus Valley civilizations was accumulated from field surveys, while most it was from the pre-historical published work of previous contributors.

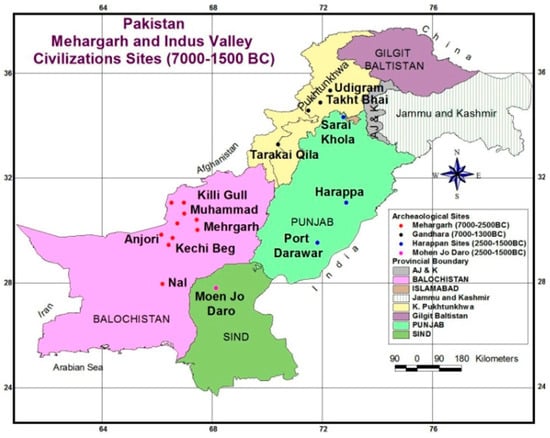

Figure 1.

Mehrgarh and Indus Valley civilizations and their major sites and interaction networks (ca. 7000–1500 BC).

This study elaborates the historical background, drainage, town planning, sanitation, toilets, sewerage, water reservoirs, baths, irrigation, wells/ground tunnels, water-related tools, and dockyards of the Mehrgarh and Indus Valley civilizations. The archaeological site of Harappa is located at 30°–53′ north latitude and 72°–75′ east longitude along the eastern bank of the Indus River in Punjab, Pakistan. Moen-Jo-Daro is located at 27°–42′ north latitude and 68° east longitude along the western bank of the Indus River, approximately 28 km southwest of Larkana city, Sindh Province, Pakistan. Mehrgarh is located at 68°–8′ east longitude and 27°–19′ north latitude near Bolan pass, Balochistan (Figure 1). As the secondary data of weather elements of that time were not available, the predictions were mostly made from the remains of vegetation, human bones, fauna, artifacts, and construction materials. The information predicted from the remains was observed in the context of the existing climate condition, as well as water technologies, and generalized for the purpose of reaching the objectives of the work.

3. Findings and Discussions

The beginning of the Neolithic era in Pakistan ranged from 7000 BC in Baluchistan to 2500 BC or afterward in Hindukush and the Himalaya Mountains, Pakistan [8,9,10]. The well-established Neolithic period is illustrated by advanced pottery, an agro-pastoral culture, population growth, stability, geographical extension, innovation in technologies such as the use of gold, seals, glazed steatite, beads, and an irrigation system [11]. The way of constructing houses, artifacts, jewelry, drainage systems, etc., were almost the same as that of Indus Valley with a joint family system; however, it was quite different from the Mehrgarh civilization in terms of construction materials, structure, and technology. Presently, the archaeological sites of Mehrgarh, Pakistan, fall in the arid climate with an annual rainfall less than 255.0 mm, except for Quetta Valley, which is in a semiarid climate (rainfall of 280–510 mm). Based on temperature, the climate of the area varies from mild to hot, except for Lasbella, where there is marine influence over land areas. The sites are located on Sibbi tableland, characterized by dry–hot weather conditions and chill burning days. As far as the archaeological sites of the same civilization (Udigram, Barikot, and Butkara) that fall in the Swat Valley, Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Pakistan, they have humid–wet climates with long cold winters and short warm summers. It is hard to examine the pre-historical weather conditions of Mehrgarh from the existing weather conditions in Baluchistan, Pakistan. Furthermore, the sites that fall in southwestern Punjab and northwestern Sind in the foothills of the Kirthar mountains represent an arid climate with long hot summers and short mild winters. It is very hard to estimate the historical climate of a place by taking into account the existing climate conditions. However, different archaeological remains and their required ecosystems, such as artifacts, flora, and fauna, as well as the social and cultural life, provide a clue to uncover the facts of the pre-historical weather and climate conditions of the area. These bases were considered for the predictions of the past climate of Mehrgarh (ca. 7000–2500 BC) and Balochistan and Indus Valley (ca. 2500–1500 BC), Sind Province, Pakistan, and are presented as follows.

3.1. Physical Settings

Plant and animal domestication was a primary adaptive tool, which contributed to the materialization of enduring sedentary settlements of Neolithic civilization, characterized by mud architecture, bone tools, blades and scrapers, packed and earth stone artifacts, and hand- or wheel-made pottery (Figure 2).

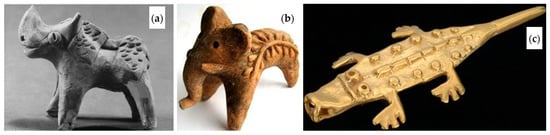

Figure 2.

(a) Vegetation artifact (dry climate) and (b) turtle and (c) elephant whistles from humid to wet climates in Mehrgarh (adapted from [8]).

The earliest evidence of pastoralism characterized by the taming of sheep, goats, and cattle with limited cereal cultivation was best documented in Kile Gul Mohammad in the Quetta Valley in Baluchistan, Udigram in Swat, Khyber Pukhtunkhwa and the contiguous area of Indus Valley in Pakistan, dated to approximately ca. 4000 BC [12]. The indigenous process of plant and animal domestication in Neolithic settlements has been traced back to as early as ca. 7000 BC near a village Mehrgarh at Bolan Pass (Kachi plains) of Baluchistan and represents a moderate weather condition [13].

3.1.1. Climate

As far as the climate of Indus Valley formulated by Sir John Marshall in the initial excavation report on Moen-Jo-Daro [14] is concerned, he accepted Stein’s opinion of drought in Baluchistan. Marshall broadened the suggestions to the Indus Valley, considering ancient data in support of his conclusion. They perhaps temporarily paraphrased mainly that the mass of Indus Valley signifies successful cultivation beyond all of the links to the existing land, which is not completely explainable by the option of a sophisticated earlier irrigation system [15]. Moreover, the animal figurine represented on the Indus seals exists in tropical forests and thus reveals a humid climate. Furthermore, the subsistence of sophisticated water supply structures may possibly have been owing to heavy precipitation. The use of a high ratio of burnt mud bricks for construction in Indus Valley settlements indicates abundant power resources and, thus, heavier precipitation.

Rainfall in Baluchistan has decreased considerably since prehistoric times because of deforestation and climate change [16]. These convictions have been broadly recognized and created the base for Sir John Marshall’s observations of the remains of the Mehrgarh and Indus Valley civilizations [14]. There are three main elements, which are, “the presence of gabarbands dams, prehistoric mounds and the depth of the mounds and cultural areas.” [15,17]. The presence of gabarbands and their canals in the Tung Valley Kirthar mountains in Sind is believed, in some cases, to be water storage dams of the Neolithic Baluchistan [14,16]. These are supposed to entail the furnishing of adequate precipitation to rationalize their construction, but were insufficient for water storage demand. Water storage dams were constructed to preserve insufficient precipitation in both civilizations. These dams appeared much more liable to have been a means, reasonably a lot booming, of initiating agriculture check dams and to have been used for the intention of familial water supply [16]. Furthermore, the establishment of Persian kareze or qanat was more important than the check dams, which tapped the underground water after ground tunnels were dug in gravel fans to capture the water table. This method of water supply is still in use in the Mehrgarh Balochistan and lower Indus plains in Pakistan.

An additional move toward the dilemma of climate variability in the Mehrgarh, Baluchistan, and Indus Valley civilizations lies in the proportional division of prehistoric and current demographic distribution. This demographic division raises queries about how and where they were living and how many of them there were. In some cases, the current model of colonization coincides with the archaeological model; in other cases, it does not coincide. In terms of synchronized models, it was observed, in the Quetta region, that the settlements themselves suggest a roughly universal distribution in the basin where productive soil and water exist at present. This shows that the climate circumstances and the natural balance of the contemporary Quetta Valley are similar to those of prehistoric times [12].

3.1.2. Disasters and Evidence (Botanical and Zoological)

In the ancient era, the inundations owing to melting glaciers were possibly higher than at present, but the summer monsoon inundations would have had a flatter shape of hydrography owing to the slowdown of surface flow by vegetation cover. This would have led to a flood regime with less variability than at present and shows a humid-to-sub-humid climate across the plain and a wet climate in the catchment area of the Indus River [18,19]. Then, there is also the matter of the affiliation of the Indus Valley civilization landmass to the flora [14,20,21] in the shape of artifacts, seals, animal bones, and figurines (Figure 3 and Figure 4). It was observed that, when the essentially recognized biological habitats of these animals, as well as vegetation, were evaluated, they were moderately affiliated than the stereotyped habitat commonly connected with them. Most previous works discussed a different habitat of flora and fauna, which comprises a mixture of dry forests, scrub forest, and marsh, a depiction which vigorously illustrates the riverine strip of the Indus civilization [15]. The botanical analysis of the remnants summarizes, “all flora and fauna remain to guide a single sense, that, 4000 years before, close to about Harappa, there was scrubby vegetation marshy patches and elevated grasslands with a limited precipitation” [22].

Figure 3.

(a) Flood deposition, (b) sand stratigraphic layers, and (c) improper laying down of bones of a mother and her child. Harappa, field visit, 2020.

Figure 4.

(a) Rhinoceros, (b) elephant, and (c) crocodile artifacts, Indus Valley, showing sub-humid-to-humid climates, (adapted from [21]).

Generally, the archeological existence of an animal artifact such as a tiger, a rhinoceros, and an elephant shows a humid climate, and that the scarcity of a camel and a lion in the Indus Valley is not in favor of an arid climate [23]. A tiger lives based on the existence of bison, elephants, deer, buffalo, wild pigs, porcupines, bears, and domesticated animals. The majority of this fauna are recognized from the current and prehistorical Indus Valley animals. On the contrary, the camel bones excavated at Mohen Jo Daro [14] and Harappa [20] indicate an arid climate, but given a complete lack of information about its natural habitat area, they do not support the arguments in any way. The rhinoceros is also known to have lived on the banks of the Indus until approximately 300 years before as far west as Peshawar [24]. Rhinoceros survive preferably in vicinities of dense grasslands and swamps beside rivers and hardly ever go into forests or mountain areas. This discussion indicates that there was an arid-to-semiarid climate in the area, but due to major rivers, the fauna were a mixture of both a humid climate in the north and an arid climate in the south and southeast of the Indus Valley civilization.

3.2. Waterlogging and Water Harvesting Systems

The lifestyle of today’s inhabitants of Baluchistan is almost entirely conditioned by the water availability and supply. All are dependent on an ancient inundation canal system such as Sailaba, khushkaba (dry farming), and such insufficient water as can be acquired from springs, wells, karezes, and small perennial watercourses. Most of them lived in similar types of homes and exploited comparatively the matching farming techniques. Most of the people, except those privileged enough to have mutually persistent water and a mild climate, migrated seasonally to the suitable areas for their survival, such as in the Bolan and Mula Pass areas, Baluchistan [25].

The deepness of masses reveals civilizing steadiness in the vicinity—a constancy whose sequence is thought to reflect an increase in precipitation in ancient times. Besides, regarding the issue of probable resettlement patterns, the archeological remains do not constantly sustain the statement of everlasting settlement with a steady environment. Certainly, some mounds may not symbolize rural community at all in the recognized logic (Figure 5).

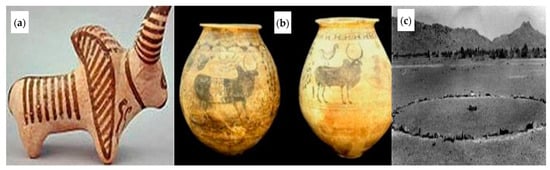

Figure 5.

(a,b) Bullock artifacts, Mehrgarh and gabarband technology, Toung Valley; (c) Kirthar Mountains, Balochistan.

This evidence is perhaps shown by the historical site of Rana Ghundhai, where the inferior fourteen feet of deposit are deficient in any structural remnants at all [17], and where the livelihood has been disturbed numerous times by means of preceding alterations in the worth and nature of the inhabiting ethnicity. The chronological farming model in Baluchistan has been influenced mainly by four physical elements, namely, prolonged drought conditions, severe floods, excess agriculture on khushkaba/sailaba terrains, and denudation of the mountains. It is concluded from the stated discussions that the location of the sites over hill slopes, artifacts of birds, seeds, crops, botanical remains, waterlogging systems, and housing structure indicate that the pre-historical Mehrgarh civilization was established in an arid-to-sub-humid climate, but due to a decrease in precipitation and an increase in temperature, population, food demand, life standards, and deforestation, the climate of the area has changed from sub-humid to arid with the passage of time (Figure 6).

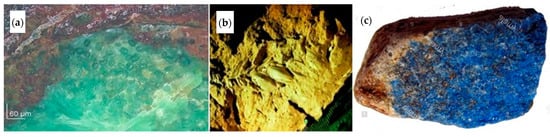

Figure 6.

(a) Mineralized cotton, (b) dry wheat, and (c) burnt/dry rice remains in Mehrgarh (ca. 7000–2500 BC), showing a warm dry climate (adapted from [3]).

Another important proof of climate is the use of the Mohen Jo Daro drainage system for a rainwater harvesting and irrigation system. For a nearby constructed city with approximately 80% of its area consisting of roofs (Figure 7). The capability of these drains does not seem fairly insufficient for rainwater, nor is there any support of the main rainwater drains into which the minor ones may possibly have linked. The single major drain is judged as an exit for the swimming pool in Mohen Jo Daro. Moreover, some streets, and so some houses, apparently had no drains. In some cases, house drains drain into sediment pits that would obviously not have been able to absorb rainwater [7].

Figure 7.

Drainage systems of the International Trade Center Harappa of the main street in Moen-Jo-Daro, Mehrgarh.

Obviously, the Mehrgarh civilization was established on the hill slopes, as well as the plain strips of hills or fans in the arid-to-semiarid region of Balochistan with scarcity of water for their survival and agriculture fields. They introduced the gabarbands and check dams to store the rain water from open areas and the khushkaba and sailaba storage system to store rainwater from the seasonal river in the valleys and to use it for their survival. These systems might be the world’s first rainwater harvesting and usage systems in desert areas (Figure 8).

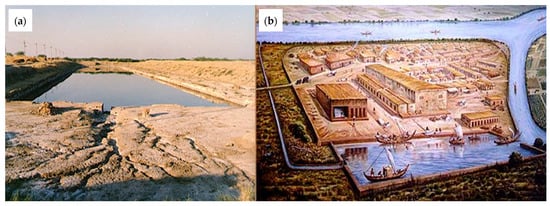

Figure 8.

(a) Water reservoir at Dholavira, (b) water dam and rivulet at Port Darawar, Indus Valley, and (c) water check dam at Toung Valley, Mehrgarh (field visit, 2020; adapted from [26]).

The Indus Valley civilization, which flourished along the banks of the river Indus and its tributaries 5000 years ago, had one of the most sophisticated urban water supply and sewage systems in the world. The fact that the people were well acquainted with hygiene can be seen from the covered drains running beneath the streets of the ruins in both Moen-Jo-Daro and Harappa. Another very good example is the well-planned city of Dholavira, on Khadir Bet, a low plateau in the Rann in Gujarat, India, and Fort Darawar, Bahawalpur, Pakistan [27]. A large number of tanks were cut in the rocks to provide drinking water to tradesmen, who used to travel along this ancient trade route. Each fort in the area had its own water harvesting and storage system in the form of rock-cut cisterns, ponds, tanks, and wells that are still in use today. A large number of forts such as Raigad and Darawar had tanks that supplied water (Figure 8).

“The kind of efficient system of Harappans of Dholavira, developed for conservation, harvesting and storage of water speaks eloquently about their advanced hydraulic engineering, given the state of technology,” [28]. One of the unique features of Dholavira is the sophisticated water conservation system of channels and reservoirs—the earliest found in the world and completely built out of stone, of which three are exposed. Dholavira had massive reservoirs (Figure 8), which were used for storing the freshwater brought by rains or to store the water diverted from two nearby rivulets. This clearly came in the wake of the desert climate and conditions of Kutch, where several years may have passed without rainfall. A seasonal stream that runs in a north–south direction of the site was dammed at several points to collect water (Figure 8). The great bath in Moen-Jo-Daro is also evidence of the water conservation and storage system [29].

The inhabitants of Dholavira created sixteen or more reservoirs of varying sizes. Some of these took advantage of the slope of the ground within the large settlement, a drop of 13 m from northeast to northwest. Other reservoirs were excavated, some into living rock. Recent work has revealed two large reservoirs, one to the east of the castle and one to the south, near the Annexe [30].

Reservoirs are cut through stones vertically, which are approximately 7 m deep and 79 m long. The reservoirs skirted the city, while the citadel and bath were centrally located on raised ground. A large well with a stone cut through to connect the drain meant for conducting water to a storage tank was also found.

It has been observed that rather than burnt brick, sun-dried mud bricks were also utilized in the Indus Valley towns. In a few instances, the mud bricks were placed in exchange ways with burnt bricks. The opinion was made that, “had the climate of Indus Valley civilization been as dry and the precipitation as low as it is nowadays,” and one can scarcely doubt that they would have used bricks dried in the sun [14]. This is an interesting declaration, keeping in mind the fact that the sun-dried bricks were utilized in constructions rather than the innermost and important formations, and burnt brick houses were actually coated with sun-dried mud plaster; moreover, the modern population builds structures with burnt bricks because of the social prestige implied in the ability to pay for them.

Presently, the annual rainfall of Mohenjo Daro is approximately 100.0 mm with a summer intensity, while in Mehrgarh, it is less than three inches (76.2 mm) with heavy showers in winter. This low precipitation indicates a small number of storms more willing than many small storms. This is a common feature of precipitation in arid/semiarid regions contiguous to sub-humid climates [31,32].

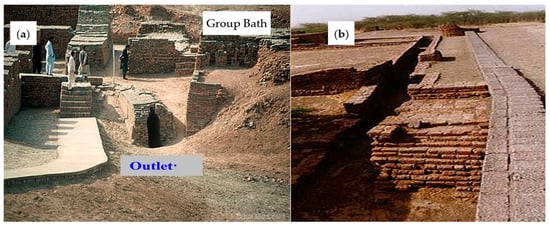

3.3. Wastewater and Sanitation Technologies

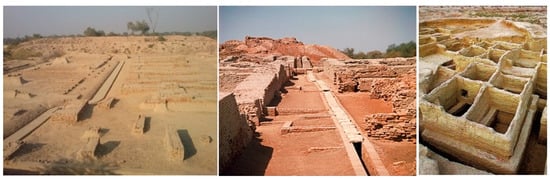

Anthropologists believe that Mehrgarh, Harappa, and Moen-Jo-Daro were archetypes of development and one of the finest examples of flourishing trade and agriculture-based economy. The people of the Indus Valley civilization made clever and resourceful use of rivers present in the area surrounding them. Mohen Jo Daro had a sophisticated system of water supply and drainage and its brickwork is highly functional and completely waterproof. The granaries were also intelligently constructed, with strategic air ducts and platforms (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Town planning of the Mehrgarh and Indus Valley civilizations (adapted from [33]).

The Mohen Jo Daro ruins present a picture of a community in which both personal and community cleanliness was quite effectively practiced, and the water supply reasonably safeguarded from contamination as a rule. Harappa town planning has stunned archaeologists worldwide. It has become a landmark for contemporary civilization when technological advancements have been made, which is helping to achieve greater heights. It has inspired the contemporary generation (Figure 9). The concept of bathing pools and granaries offers a glimpse of modern-day swimming pools and storehouses, where the grains can be stored. It was a properly furnished city, which facilitated Harappa dwellers to live a luxurious life with proper sanitation and regulation [32].

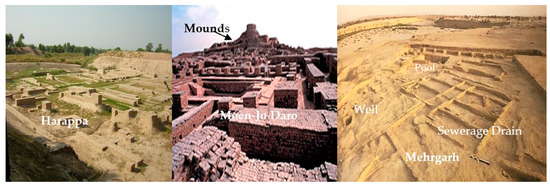

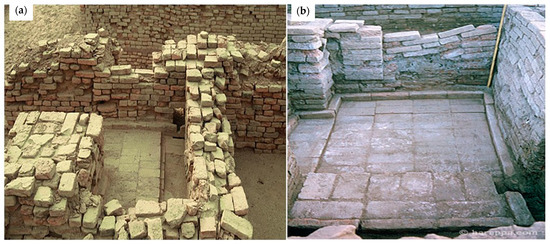

Due to mud-constructed walls and earth dug drains, archeologists know very little about the sanitation and wastewater technologies of Mehrgarh. This is because most of the evidence was washed by rainwater or wind storm abrasion and collision process as well as water erosion. However, the remains at Kalli Gull Muhammad and Bolan pass, Baluchistan, indicate that they have a main drain at the sides of their residences and that the rain water fall down to it directly from the roofs and houses. The construction of houses in a grid system reveal that there was a common wall between two houses and in the middle, and in the corner of the house, there was a toilet and bath. Outside the constructed area, there was a check dam for the storage of rainwater with an open inlet drain from the slope or elevated areas (Figure 10).

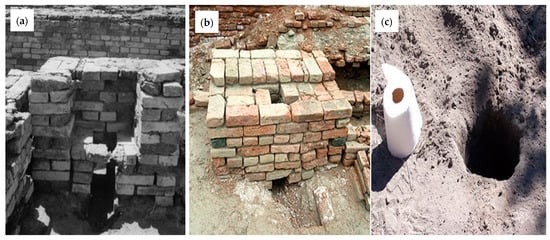

Figure 10.

(a) Drainage system and (b,c) sanitation systems of the Indus Valley civilization (adapted from [33]).

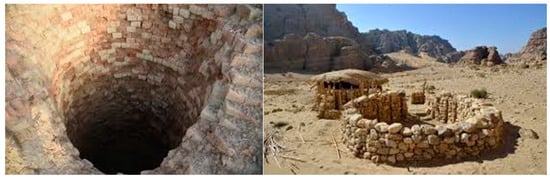

The check dams were used as a swimming pool and also for domestic water use. A common well also existed in Kalli Gull Muhammad, as well as Bolan Pass, with spring water in nearby valleys. This evidence indicates that they had common use of wells, as well as spring water, which shows their unity and coordination with one another.

The Harappan town had a very good drainage and sanitary system. The main drain was associated with each and every house, ensuring the proper dumping of waste. In order to check the maintenance, inspection holes were provided. The drains were covered and connected to the bigger sewerage outlets, which ensured the channel of dirt out of the city. For water, the big houses had their own wells; other wells served groups of smaller houses. Almost every house had a bathroom, usually a fine sawn burnt brick pavement, often with a surrounding curb. The house drains started from the bathrooms of the houses and joined up to the main sewer in the street, which was covered by brick, slabs, or corbelled brick arches. On the streets were manholes for cleaning; some drains flowed to closed seeps, while others flowed out of the city [34]. These water wells and the well-planned sanitation and sewerage system are some of the great signs that lead to the Indus Valley civilization being well developed [35].

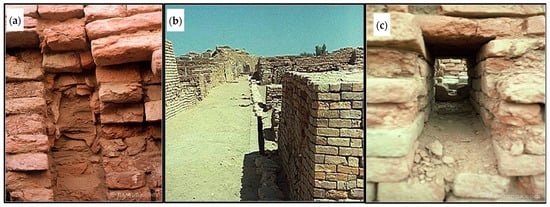

The bath and kitchen waters, as well as drainage from the latrines and the roof, usually did not run into the street drains direct, but entered them via tightly brick-lined paths, with outlets to the street drains about three-quarters of the distance above the bottom (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

(a) Wastewater management system, (b) water supply terracotta pipeline, (c) main hole, and (d) water tank of the Indus Valley civilization.

Apparently, these pits were cleaned out from time to time, as being the setting basins or soakage pits located along the street drains. These pits may have been the ancient precursors of our present-day septic tanks and grit chambers. In some houses, drainage water was discharged into large pottery jars placed in the street at the foot of the vertical drains in the street walls [36]. Houses also had rubbish chutes built into the walls that descended from the upper floors, at the foot of which bins were sometimes provided at the street level, which could be cleaned out by scavengers. Public rubbish bins were also provided in convenient places [36].

The Mehrgarh people were developing the concept of a swimming pool or ground water logging system. In the northwestern part of Kalli Gull Muhammad remains, there is a square-shaped pool or water tank on the ground with an open area around it. This indicates that they had a swimming pool or open earth water tank system. This swimming pool is some distance from the water check dam of the settlement, with an inlet and an outlet on the eastern and western sides. The base of the tank is approximately six feet deep and its walls are made of stone compacted by clay. However, due to erosion, most of the evidence has been washed away and it is very hard to promote these predictions without further digging on the site. Furthermore, the evidence of gabarbands in Tung Valley, Sind, also represent the waterlogging technology of the Mehrgarh people for agricultural purposes, the latter of which might have been converted into check dams, as well as hydro-dam technology.

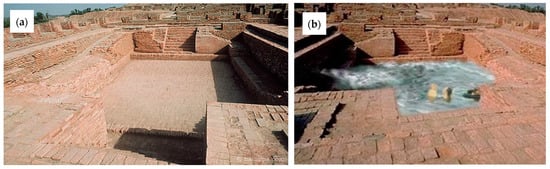

The “great bath” is, without doubt, the earliest public water tank in the ancient world, located at the archeological site of Moan Jo Daro. The tank itself measures approximately 12 m north–south and 7 m wide, with a maximum depth of 2.4 m [37]. Two wide staircases lead down into the tank from the north and south, and the small sockets at the edges of the stairs are thought to have held wooden planks or treads. At the foot of the stairs is a small ledge with a brick edging that extends the entire width of the pool. People coming down the stairs could move along this ledge without actually stepping into the pool itself (Figure 12). The floor of the tank is water-tight due to finely fit bricks laid along edge with gypsum plaster, and the side walls were constructed in a similar manner. To make the tank even more water-tight, a thick layer of bitumen (natural tar) was laid along the sides of the tank and, presumably, also beneath the floor. Brick colonnades were discovered along the eastern, northern, and southern edges. The preserved columns have stepped edges that may have held wooden screens or window frames. Two large doors lead into the complex from the south and other access was from the north and east. A series of rooms are located along the eastern edge of the building, and in one room, there is a well that may have supplied some of the water needed to fill the tank. Rainwater also may have been collected for these purposes, but no inlet drains have been found [38].

Figure 12.

Great bath at Moen-Jo-Daro: (a) Empty view and (b) with water (adapted from [33]).

The principal community bath was a structure of considerable size, conforming somewhat to our ideas of a swimming pool, though perhaps being used rather as a place for religious ceremonials than for either mere pleasure or for only the cleansing of the body. The structural features of the pool indicate an excellent ability in construction, considering the building materials available at that time and place. For example, waterproofing was accomplished by a membrane or coating of aspartame between the inner and outer walls of the pool or tank [36].

The Mehrgarh and Indus Valley civilizations were known for their water management [39]. They prayed to the rivers every day and gave them a divine position. They had well-constructed wells, tanks, public baths, a wide drinking system, and a city sewage system. Each city had two regions—a higher ground, which contained the “Citadel,” which was the main administrative area, and the lower city, where the houses were situated. All the important areas were situated on the higher ground. The baths and wells were situated there, which suggests the importance they were given [40]. However, in Neolithic Mehrgarh, the water wells, as well as water tanks, seem to be on one side of the village or constructive area. There is no evidence of individual wells, water tanks, or storage systems. The main drain seems to be around the constructed area with some link drains from the houses. No doubt, the water management system of the Mehrgarh civilization was not well developed, but it provides a clue for the promotion of water technology for the future (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

(a) Great bath outlet, Moen-Jo-Daro, and (b) Lothal sanitation (adapted from [33]).

Resultantly, the water treatment and sewage system of the Indus Valley civilization was more advance compared to the Neolithic era in Pakistan. The inhabitants of Moen-Jo-Daro were masters in constructing wells. It is estimated that approximately 700 wells have been built within their city, an average of one well for every three houses. They were constructed with tapering bricks that were strong enough to last for centuries.

The cities too had strong walls to resist damage due to floods. One reason for this large number is that Moen-Jo-Daro received less winter rain and was situated further from the Indus River than the other prominent cities. Hence, it was necessary to collect and store water for various purposes. Unlike the wall that exists around the historical remains of Harappa, the villages of Mehrgarh were constructed without any wall around with a single well and groundwater tank.

3.4. Baths and Toilets

The Mehrgarh village of Kalli Gull Muhammad, as well as Bolan Pass remains, indicate that they had a well and water tank, as well as baths. The well and water tank were a common entity to facilitate the whole village. In the houses, between bedrooms, there are small square-shaped units in the form of a row, which shows that these were the baths, as well as toilets, which exist in almost all houses. As the civilization was mostly based on a village system, there was the concept to use the open air as a toilet. However, it was their big contribution for the coming generation to promote the concept of wells, as well as bath and toilet systems (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

(a) House bathroom and outlet, and (b) house bathing platform in Moen-Jo-Daro (adapted from [33]).

One of the best-known excavations is the Great Bath of Moen-Jo-Daro, which has been discussed before. In addition to wells, archaeologists have also found the remains of giant reservoirs for water storage. The reservoirs were situated around the metropolis, which was fortified with stone walls. The Archaeological Survey of India revealed that one-third of the area of the city of Dholavira in the Rann of Kutch was devoted to the collection and distribution of freshwater. The city was situated on a slope between two streams. At the point where one of the streams meets the city’s walls, people carved a large reservoir out of rock. This was connected to a network of small and big reservoirs that distributed water to the entire city all year round. All of the reservoirs together could hold approximately 248,480 m3 of water. Such was the importance they gave for water storage. According to [36], many of the houses of the Indus civilization had their individual wells within buildings.

These wells were usually circular in plan, though at times were oval, and had copings of stones or bricks at the floor level, and brick lining for a moderate depth below the surface. In a few instances, the street drain ran rather too close to the wells, and it is possible that some contamination of the well occurred. However, in most cases, the wells were located at adequate distances from the drains.

Generally, the Moen-Jo-Daro ruins present a picture of a community in which both personal and community cleanliness were quite effectively practiced, and the water supply reasonably safeguarded from contamination as a rule. Practically every house in Moen-Jo-Daro had a bathroom, always placed on the street side of the building for the convenient disposal of wastewater into the street drains. Where latrines have been found in the houses, they were placed on the street wall for the same reason. Ablution places were set immediately adjacent to the latrines, thus conforming to one of the most modern sanitary maxims. Where baths and latrines were located on the upper floor, they were drained usually by vertical terracotta pipes with close-fitting spigot joints, set in the building wall (Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 15.

(a) Well and (b) upland water tank of the Indus Valley civilization (adapted from [33]).

Figure 16.

Well technology of the Neolithic Mehrgarh.

In the bathroom, people stood on a brick “shower tray” and tipped water over themselves from a jar. The clean water came from a well. Dirty water drained through a pipe out through the wall into the drain in the street [41]. These ancient terracotta pipes, still sound after nearly five thousand years, are the precursor of our modern verified clay spigot-and-socket sewer pipes and are an excellent guarantee of the durability of this material.

In each society, from time to time, the administration felt the need to provide public toilet facilities to those who could not afford to have individual toilets. Public toilets have a long history in a number of countries, and most of these were constructed and managed by municipalities. However, there was all around disgust with their poor maintenance, vandalism, and lack basic facilities [42]. In the absence of proper toilet facilities, people perforce had to defecate and urinate wherever they could. Defecating on the road, open spaces, agriculture fields, pools, or just easing themselves in the river was very common (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

(a) Bricks, (b) toilet seats, and (c) open-air toilet tunnel in Indus Valley (adapted from [43]).

The third millennium BC was the “Age of Cleanliness.” Toilets and sewers were invented in several parts of the world, and Moen-Jo-Daro ca. 2800 BC had some of the most advanced, with lavatories built into the outer walls of houses. These were primitive, “Western-style” toilets made from bricks with wooden seats on top. They had vertical chutes, through which waste fell into street drains or cesspits [42].

The toilets at Moen-Jo-Daro, built around 2600 BC, were only used by the affluent classes. Most people would have squatted over old pots set into the ground or used open pits. The people of the Indus Valley civilization in Pakistan had primitive water-cleaning toilets that used flowing water in each house that was linked with drains covered with burnt clay bricks. The flowing water removed human waste [44].

Toilets would have been an essential feature in Moen-Jo-Daro, but the early excavators identified most toilets as post-cremation burial urns or sump pots. This brick structure had a hole in the top that was connected to a small drain leading out of the base into a rectangular basin (not reconstructed). Early excavators suggested that structures with a hole and drain are toilets. For human urinate, they may have used a hole in the ground at open places that connected to a nearby drain. The toilets of the Indus Valley civilization were different than the Roman and Greek civilizations. This difference is the main evidence of the cultural difference between them [44].

3.5. Land Drainage Systems

Generally, the Neolithic Mehrgarh is known as the village system with some compact and disperse house systems. The drain around the village and that of waterlogging check dams indicate that they were aware of the drainage system, but were not well-developed technologically. It is hard to observe the well-developed drainage system in Neolithic Pakistan, as most of these sites exist in arid areas and were made of mud and clay burnt bricks, as well as hill rocks, and were damaged due to heavy rain in the area or, in some cases, washout from the ground. However, the cultivation of cotton, wheat, barley, and domestication of animals shows that they were aware of canals and irrigation systems too.

The Indus civilization had an elaborate sanitary and drainage system, the hallmark of ancient Indus cities. Each and every house had a connection to the main drain. These even had inspection holes for maintenance. The conduits to the main drains ran through the middle of the streets below the pavement level and were covered with flat stones and sturdy tile bricks. The covered drain was connected to the larger sewerage outlets, which finally led the dirty water outside the populated areas. The urban plan found in these cities included the world’s first urban sanitation system. The elaborate brick-linked drainage system for the removal of rainwater is of unparalleled engineering skill [45].

Every house had a drinking water well with a private bathroom. Earthenware waste pipes carried sewage from each home into covered channels that ran along with the centers of the city’s main streets into nearby agricultural fields, rivers, or streams. The drain took waste from kitchens, bathrooms, and indoor toilets. The main drains even had movable stone slabs as inspection points. The houses had excellent plumbing facilities for the provision of water [45].

Toilets had brick seats, and they were flushed with water from jars. The waste flowed out through clay pipes into a drain in the street. Waste was carried away along the drains to “soak pits” (cesspits). Cleaners dug out the pit and took the waste away. They also took away rubbish from bins on the side of houses. Each street and lane had one or two drainage channels, with brick or stone covers that could be lifted to remove obstructions in the drains. The drains usually ranged from 46 to 61 cm below street level, and varied in dimensions from 30.50 cm deep and 23.00 cm wide [36]. When the drain could not be covered with flat bricks or stone slabs, the roof of the drain was corbelled.

The Lothal town planning represents a structure of the dockyard, the industrial and trade center of the Indus Valley civilization (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Dockyards at (a) Lothal and (b) Courtesy (adapted from [33]).

The whole town was situated on a patch of high ground. Rising from the flat alluvial plains of Bhal, a wall was erected to encircle the town, and a platform was built where goods were checked and stored. The warehouse was divided into 64 rooms of around 3.5 m2 each, connected by 1.2 m wide passages [46].

The dominant sight at Lothal is the massive dockyard, which has helped make this place so important to international archaeology. Spanning an area of 37 m from east to west and nearly 22 m from north to south, the dock is said by some to be the greatest work of maritime architecture before the birth of Christ [46]. To be sure, not all archaeologists are convinced that the structure was used as a dockyard, and some prefer to refer to it as a large tank that may have been a reservoir (Figure 18).

It was excavated beside the river Sabarmati, which has since changed course. The structure’s design shows a thorough study of tides, hydraulics, and the effect of sea water on the bricks. Ships could have entered into the northern end of the dock through an inlet channel connected to an estuary of the Sabramati during high tide. The lock gates could then have been closed so the water level would rise sufficiently for them to float (Figure 18).

An inlet channel 1.7 m above the bottom level of the 4.26 m deep tank allowed excess water to escape. Other inlets prevented siltation of the tanks and erosion of the banks. After a ship would have unloaded its cargo, the gates would have opened and allowed it to return to the Arabian sea waters in the Gulf of Combay [46,47].

3.6. Irrigation Systems

The archaeological evidence of the Neolithic Mehrgarh (ca. 7000–2500 BC) regarding cotton, burnt rice, wheat, and barely indicates that they had the concepts of agricultural practices and irrigation systems in that era. The remains of the gabarbands, check dams, khushkaba, and sailaba system in the nearby valleys of the Mehrgarh settlements prove that they had a well canal and irrigation system in the entire area for the cultivation of food and cash crops (cotton, burnt rice, wheat, and barley). Because, from each gabarband, check dam, khushkaba, and sailaba, there are a number of outlet channels that represent a clue of canals to the agricultural fields near the archaeological sites of Bolan Pass, as well as Kalli Gull Muhammad. They were also experts in the storage of rain, as well as a tape water system, and used them for domestic and agricultural systems (Figure 19).

Figure 19.

Irrigation systems of Indus Valley and Mehrgarh (adapted from [48]).

The Indus Valley civilization in Pakistan (ca. 2600–1500 BC) also had an early canal irrigation system. Large-scale agriculture was practiced and an extensive network of canals was used for the purpose of irrigation. Sophisticated irrigation and storage systems were developed, including the reservoirs built at Girnar in ca. 3000 BC [47]. Moreover, some of the toy pictures of the Indus Valley civilization indicate that there was a proper system of water supply in different houses and places.

Mostly, women had the responsibility of supplying water in different places. Farmers made good use of water from the rivers. They sowed seeds after the rivers had flooded the fields, as floodwater made the soil rich. They planted different crops for winters and summers. They were probably the first farmers to take water from underground wells and use it as a karaze system using bulls. They may have used river water to irrigate their fields. Their main cultivation products, amongst others, were peas, sesame seeds, and cotton. They also domesticated wild animals in order to use them for harvesting their farms [49].

4. Conclusions and Remarks

The Mehrgarh civilization was flourishing in the hilly areas and a plain strip of mountains in Balochistan during ca. 7000–2500 BC, with major archeological sites such as Kalli Gull Muhammad, Bolan Pass and Charsadda, Takht Bhai, and Udigram (Swat) in Khyber Pukhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan. The existing climate of Balochistan is arid, sub-humid in Charsadda, Takht Bhai, and humid climate in Udigram Swat. However, the archeao-botanical, drainage, cropping pattern, and artifacts of animals show that the climate of Balochistan during the Neolithic era was semiarid to sub-humid with an arid climate at the coastal belt. Currently, the climate of the Indus Valley civilization (ca. 2500–1500 BC) is arid, where the amount of precipitation is less than 255.0 mm; however, the archeological remains such as animals’ artifacts, vegetation cover, agriculture, drainage, and sanitation system indicate that there was an arid-to-semiarid climate condition during the Indus Valley era.

As far as the water and sanitation system of the Neolithic Mehrgarh has been considered, they had complete knowledge of sanitation, canal systems, construction of water dams, wells, water tanks, agriculture, trade, sewers, and business systems. The developed structure of that culture then appeared in the shape of the Indus Valley civilization in the central Punjab and Sind provinces, Pakistan.

By approximately 1700 BC, the Indus Valley and Mehrgarh civilizations were on the verge of decline. The causes of this decline are not certain. The physical existence of the civilization ended due to various factors, as given below.

- (a)

- Ecological changes led to a decline in land and agriculture, thereby enforcing the need to evacuate to other areas, which might have been the reason for the disintegration of the Indus Valley civilization. Shifts in the monsoon pattern and changes in temperature led to the area becoming even a rider [2].

- (b)

- An increase in population, excessive deforestation, and a decline in agriculture might have created economic problems, leading to the gradual decay of the cultures. The marked decline in the quality of the buildings and town planning indicates that the authorities were losing control with the passage of time.

- (c)

- The changes in the Indus flow in Punjab and different rivers in Balochistan and the correspondent widespread flooding would have disrupted the agricultural base and destroyed the civilizations or might have forced them to migrate into the nearby suitable areas for their survival. Due to climate change (increase in aridity and raise in temperature), most of the inhabitants of the Mehrgarh and Indus Valley civilizations may have migrated to other places in search of suitable environmental conditions.

- (d)

- The invasion of the Aryans in Balochistan, as well as Sind, is the other view that is said to be another reason that might have also led to the decline of the Indus Valley and Mehrgarh civilizations. Thus ended the most brilliant civilizations of the ancient world.

- (e)

- It is hypothesized that the destruction of the Indus Valley civilization, as well as the Neolithic Mehrgarh, was the result of an earthquake caused by tectonic movement of the Indian plate. This earthquake was caused at night time, when most of the people were asleep. The dead bodies buried in the Harappa, Moen-Jo-Daro, Kalli Gull Muhammad, Uidgram, Charsadda, and Takht Bhai sites are evidence of the earthquake disaster, as most of them lay properly, along with juveniles and family, without any proper digging of graves. The people who were safe and alive shifted to other areas and constructed new sites for survival. However, this needs further research to study the evidence of the earthquake disasters that destroyed the Indus Valley and Neolithic Mehrgarh civilizations.

The Indus civilization was known for its well-planned drainage, sanitation system, dockyards, sewers, baths, toilets, irrigation, agriculture, and hydraulic engineering. The houses had their own wells, bathrooms, and toilets. Almost every house had a bathroom, usually a fine sawn burnt brick pavement, often with a surrounding curb. The house drains started from the bathrooms of the houses and joined up to the main sewer in the street.

The proud people of Indus were docile, peace-loving, and accommodating, whereas those of Mehrgarh were worriers. The Indus person demonstrated tolerance and broad-mindedness, whereas the Mehrgarh people were non-developed, honorable, rich, well planned, and sharp-minded. Our quest to search for our identity has taken us to the land of the Mighty Indus. There is absolutely no doubt that the Pakistani are the people of the forgotten Indus and Mehrgarh civilizations, who were docile, peace-loving, accommodating, moderate, and open-minded—traits that we have lost. It is time to rediscover and restore Pakistan as a liberal, progressive, modern Muslim state with its rightful place in the community of nations. Future studies should focus on how we can take advantage of the history of the hydro-technologies of the Mehrgarh, Baluchistan. and Indus Valley civilizations to meet sustainable development in the future with respect to the importance of these regions [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58].

Author Contributions

S.K. had the original idea, prepared the original draft of the manuscript, and revised and edited it. N.Y., M.V. and A.N.A. revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly acknowledge Cynthia Lynn Hann for her considerable contribution to improvement of the English grammar and fluidity in the development of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Smith, M.L. The archaeology of South Asian cities. J. Archaeol. Res. 2006, 14, 97–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carry, T.J. The Harappan Civilization, Archeology. 2012. Available online: http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/harappa-mohenjodaro.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Khan, S.; Ismail, A. Socio-Cultural and Public Administration of Neolithic Mehrgrah, Baluchistan, Pakistan Civilization (7000–2500 BC). Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. Work. 2019, 6, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, R.P. The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: http://www.amazon.com/The-Ancient-Indus-Urbanism-Societies/dp/0521576520 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Kosambi, D.D. The Culture and Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline; Poona Publisher: Poona, India, 1964; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, L.P. Ancient India History, Indus Valley Civilization. 1992. Available online: http://www.culturalindia.net/indian-history/ancient-india/indus-valley.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Angelakis, A.N.; Rose, J.B. Evolution of Sanitation and Wastewater Technologies through the Centuries; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2014; p. 600. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrige, C. The Figurines of the First Farmers at Mehrgarh and their Offshoots. Pragdhara 2008, 18, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, G. The Indus Valley Civilization and Early Tibet; Senri Ethnological Reports; National Museum of Ethnology: Osaka, Japan, 2000; Volume 15, pp. 651–670. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, N.; Fuller, D.Q.; Korisettar, R.; Petraglia, M.D. First Farmers in South India: The role of internal processes and external inuences in the emergence and transformation of south India’s earliest settled societies. Pragdhara 2008, 18, 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kenoyer, J.M. The Indus Civilization. In Encyclopedia of Archaeology; Pearsall, D.M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 715–733. [Google Scholar]

- Fairservis, W.A. The Threshold of Civilization: An Experiment in Prehistory; Scribner’s and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Lemmen, C. A simulation of the Neolithic transition in the Indus valley. In Climates, Landscapes, and Civilization; Poona Publisher: Poona, India, 2012; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal, L. Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization; A. Probsthain: London, UK, 1931; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, S.M. The Cambridge History of India. The Indus Civilization; Cambridge, at the University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1953; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, S.A. An Archaeological Tour of Gedrosia. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India 43; Government of India Press: New Delhi, India, 1931; p. 70.

- Piggot, S. Prehistoric India to 1000 B.C. Harmondsworth (Middlesex); Penguin Books: London, UK, 1950; p. 360. [Google Scholar]

- Pithawala, M.B. An Introduction to Sind: Its Wealth and Welfare; Sind Observer Press: Karachi, Pakistan, 1951; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Soate, O.H.K. India and Pakistan. A General and Regional Geography; Methuen and Company: London, UK, 1954; p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- Prashad, D. Animal Remains from Harappa. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India 51; Government of India Press: New Delhi, India, 1936; p. 300.

- Petrie, C.A.; Ceccarelli, A. Cultural Evolutionary Paradigms and Technological Transformations from the Neolithic up to the Indus Urban Period in South Asia; Archaeopress Archaeology: Oxford, UK, 2018; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, Y.K.; Ghosh, C.S. Plant-remains from Harappa, 1946. Ancient India 1951, 7, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.A. The Vertebrate Zoology of Sind; Richardson and Company: London, UK, 1884; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, F. Extinct and Vanishing Mammals of the Old World; New York Zoological Park: New York, NY, USA, 1945; p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- De Cardi, B. Fresh problems from Baluchistan. Antiquity 1959, 33, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, A.; Tsatsanifos, C.; El Gohary, F.; Palerm, J.; Khan, S.; Mahmoudian, S.A.; Ahmed, A.T.; Tayfur, G.; Dialynas, Y.G.; Angelakis, A.N. Developments in water dams and water harvesting systems throughout history in different civilizations. Int. J. Hydrol. 2018, 2, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kenoyer, J.M. The Indus Valley tradition of Pakistan and Western India. J. World Prehist. 1991, 5, 331–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, T.S. The rise and fall of a Harappan city. Frontline India’s Natl. Mag. Publ. Hindu 2010, 27, 5–18. Available online: http://www.frontlineonnet.com/fl2712/stories/20100618271206200.htm (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Violett, P.L. Water Engineering in Ancient Civilizations: 5000 Years of History; (Translation into English by Forrest M. Holly); International Association of Hydraulic Engineering and Research (IAHR): Madrid, Spain, 2007; Available online: http://www.amazon.com/Water-Engineering-Ancient-Civilizations-Monographs/dp/9078046058 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Wales, J. Dholavira, Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. 2010. Available online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dholavira#cite_note-frontline-1#cite_note-frontline-1 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Dyson, R.H.; Raikes, R.L. The Prehistoric Climate of Baluchistan and the Indus Valley. In American Anthropologist; Hunting Technical and Exploration Services, Ltd.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1961; pp. 265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, S. Harappa and Mohenjo Daro. 2012. Available online: http://ugghani.blogspot.in/2012/06/harappa.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Kenoyer, J.M. Mohenjo-Daro, an Ancient Indus Valley Metropolis; University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 1998; Available online: http://www.harappa.com/indus3/kenoyer.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Jansen, M. Mohenjo-Daro, City of the Indus Valley, Endeavour; New Series; Pergamon Press: London, UK, 1985; Volume 9, p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.E.J. Urban Hydrology—A Redirection. Civ. Eng. 1967, 37, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, H.F. Sewerage in Ancient and Mediaeval times. Sew. Works J. 1940, 12, 939–949. [Google Scholar]

- Deonarine, A.; Jim, M.; Khan, O. “Great Bath”, Mohenjo-daro. 1995. Available online: http://www.harappa.com/indus/8.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Saffy, H. The Great Bath at Moenjodaro, Wikipedia Online. 2011. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Bath,_Mohenjo-daro (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Jansen, M. Water Supply and Sewage Disposal at Mohenjo-Daro. World Archaeol. 1989, 21, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, A. Indus Valley—How They Managed Their Water Resources, Water Management in the Ancient Indus Valley. 2006. Available online: http://voices.yahoo.com/indus-valley-they-managed-their-water-resources-82580.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Lofrano, G.; Brown, J. Wastewater Management Through the Ages: A history of Mankind. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 5254–5264. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20817263 (accessed on 14 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Pathak, B. The History of Toilets. International Symposium on Public Toilets, Hong Kong. 1995. Available online: http://www.plumbingsupply.com/toilethistoryindia.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Antoniou, G.; De Feo, G.; Fardin, F.; Tamburrino Tavantzis, A.; Khan, S.; Fie, T.; Ieva Reklaityte, I.; Kanetaki, E.; Zheng, X.Y.; Mays, L.; et al. Evolution of Toilets Worldwide Through the Millennia. Sustainability 2016, 8, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hooper, A. What Is the Complete History of the Toilet? 2011. Available online: http://answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20120220121010AARe9nX (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Rothermund, D.; Kulke, H. A History of India, 4th ed.; Routledge Publishing: London, UK; New Delhi, India, 1998; Available online: http://www.fsmitha.com/h1/ch05.htm (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Mulchandani, A.; Shukla, D. A walk through Lothal. 2010. Available online: http://www.harappa.com/lothal/index.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Shirsath, P.B. Irrigation Development in India: History & Impact; Water Technology Centre, WTC, IARI: New Delhi, India, 2009; Available online: http://indiairrigation.blogspot.com/2009/01/history-of-irrigation-development-in_01.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Angelakιs, A.N.; Zaccaria, D.; Krasilnikoff, J.; Salgot, M.; Bazza, M.; Roccaro, P.; Jimenez, B.; Kumar, A.; Yinghua, W.; Baba, A.; et al. Irrigation of World Agricultural Lands: Evolution through the Millennia. Water 2020, 12, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, A. Boring no more, a trade-savvy Indus emerges. Science 2008, 320, 1276–1281. Available online: http://www.academicroom.com/article/boring-no-more-trade-savvy-indus-emerges (accessed on 14 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Dialynas, E.; Kasaraneni, V.K.; Angelakis, A.N. Similarities of Minoan and Indus Valley hydro-technologies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Valipour, M.; Choo, K.-H.; Ahmed, A.T.; Baba, A.; Kumar, R.; Toor, G.S.; Wang, Z. Desalination: From Ancient to Present and Future. Water 2021, 13, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, M.; Bateni, S.M.; Dalezios, N.R.; Almazroui, M.; Heggy, E.; ¸Sen, Z.; Angelakis, A.N. Hydrometeorology: Review of Past, Present and Future Observation Methods; Theodore, V., Hromadka, I.I., Prasada, R., Eds.; Hydrology, IntechOpen Publisher: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S.; Das, S.S.; Mishra, P.; Al Khatib, A.A.G. Time Series SARIMA Modelling and Forecasting of Monthly Rainfall and Temperature in the South Asian Countries. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 5, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Shinde, V.; Kim, Y.J.; Woo, E.J.; Jadhav, N.; Waghmare, P.; Yadav, Y.; Munshi, A.; Panyam, A.; Chatterjee, M.; et al. Craniofacial reconstruction of the Indus Valley Civilization individuals found at 4500-year-old Rakhigarhi cemetery. Anat. Sci. Int. 2019, 95, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameer, M.A.; Juzhong, Z.; Miao, Y.M. Approaching the origins of rice in China and its spread towards Indus valley civilization (Pakistan, India): An Archaeobotanical Perspective. Asian J. Res. Crop. Sci. 2018, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameer, M.A.; Zhang, J.Z. A case study on intangible cultural heritage of indus valley civilization: Alteration and re-appearance of ancient artifacts and its role in modern economy. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2018, 9, 29898–29902. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R. Early Description of Numerical and Measuring System in Indus Valley Civilization. Int. J. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2019, 6, 1586–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, A. The Indus: Lost Civilizations; Reaktion Books; Reaktion Books Publisher: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).