1. Introduction

The year 2020 is an emblematic year for the human rights to water and sanitation (HRtWS). It is the last year of the second mandate of the Special Rapporteurs (SRs,

Appendix A (1)), both appointed by the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council (HRC). It is the year when the 10th anniversary of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Resolution 64/292 [

1] recognizing the HRtWS is celebrated. It is the fifth year since the adoption of Agenda 2030, in which the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets 6.1 and 6.2 are aligned with the human rights (HR) framework. Unfortunately, 2020 is also the year when the COVID-19 pandemic emerged and spread worldwide, affecting millions of people, a situation exacerbated by insufficient access to water for handwashing, a key primary barrier against the virus.

The adoption of the Resolution by the UNGA in 2010 is a landmark in a long line of milestone dates that can be traced back to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, that, in its Article 25 states that: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care…”. After a series of developments from this Article, in 2002, General Comment No.15 [

2] clarified the meaning of the right to water and established the ground for further resolutions, starting with Resolution 64/292. The progression of UNGA and HRC resolutions since 2010 have deepened the understanding of what the HRtWS entail and how they are to be realized.

The 2010 UNGA resolution was significant because it was not a resolution only promoted by northern countries looking to influence development policy in developing countries, but was led by Bolivia. It was through active diplomacy that the 2010 UNGA resolution includes sanitation. This has been critical for all later discussions on the HR, elevating the right to sanitation to the same level of importance as the right to water, supporting its strengthened in the SDGs with the inclusion of a dedicated target on sanitation (SDG6.2).

A few countries—Uganda, South Africa, Uruguay, Nicaragua, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ecuador, Maldives, and Bolivia—had already recognized the human right to water (or water and sanitation) in their constitutions, but recognition at the UNGA increased attention to these rights, and, through active civil-society advocacy and lobbying, more countries have now incorporated the HRtWS into their constitutions and national legislative frameworks.

More significantly, recognition of the HRtWS has enabled focused conversations between governments, civil society groups, service providers and development professionals on how to integrate HR principles into policies and plans. The need to eliminate inequalities and address discriminatory practices is clear when we look at the statistics at the end of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) period. The MDGs did not specify where improvements needed to be made, for example, in ‘halving the proportion of people without access to water’—so while the MDG target for water was indeed met, when we observe the statistics of who benefitted most, we can see from Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) data that it was not the poorest households, but rather those who already had some level of service that received a better service. The HR principles of equality, of participation and of access to information made these inequalities no longer acceptable, such that the SDGs created quite different language, including ‘Leaving no-one behind’, which is the battle cry of many civil society organisations in the implementation of Agenda 2030.

The HRC created the mandate of (initially) the Independent Expert on human rights issues relating to water and sanitation in 2008. The decision to create the madate followed the 2002 adoption of General Comment No.15 on the right to water, an OHCHR study in 2005 and a push from Germany and Spain to consider the human rights to water and sanitation more consistently, all of which increased interest in the issue. In 2011, following recognition of the rights to both water and sanitation in 2010, the mandate was formalised as the Special Rapporteur on the human rights to water and sanitation. Since the beginning of their mandates, the UN SRs have attempted to clarify the content of the HRtWS, how they relate to different actors and stakeholders and how they can be implemented practically. The main instruments for this work are country visits, undertaken at the invitation of the respective governments, and thematic reports covering a range of topics, submitted to the UNGA and the UN HRC These reports covered many topics, from the first in 2009 where the Special Rapporteur (SR) clarified the content and critical considerations of the human right to sanitation, to the latest in 2020, where the risks that privatization of water and sanitation services pose to the HRtWS were discussed. The first SR published two books, namely one compiling good practices in realising the HRtWS [

3] as well as a handbook on the HRtWS [

4], which spells out how governments can integrate the HRtWS into their work. The second Rapporteur developed a follow-up exercise of seven of his country missions, allowing him to assess the progressive realization of the human rights instead of just assessing the country’s situation at one point in time during the country mission. This project was quite unprecedented for the Special Procedures system. Although the mandate-holders are encouraged by the HRC to undertake such exercises, it is expensive and time-consuming, and difficult for the experts to accommodate in their already busy agenda.

The SR on the HRtWS is part of the Special Procedures of the HRC, which comprise 44 thematic and 12 country mandates as of August 2017 (

Appendix A (2)). The mandate-holders are independent experts and are required to report annually to the HRC and to the UNGA on issues related to the scope of their mandates, including the submission of thematic reports and country mission reports. The Special Procedures system covers different aspects of civil, cultural, economic, political, and social rights. The mandate-holders are encouraged to interact on issues that are common to more than one mandate and this is frequently practised in communications to State members and other actors on alleged violations of HR. A challenge, however, is to strengthen the common work of mandate-holders in country missions and in analysis of cross-cutting issues. The SRs on the HRtWS have experienced some joint country missions, namely the mission to Bangladesh in 2010 (with the SR on extreme poverty) and the mission to Portugal in 2016 together with the SR on housing, which allowed the integrated assessment of the interrelation of different HR policy, regulation and financing aspects in the country.

In the contemporary world, the contingencies that the population will increasingly need to live with and the related impact on access to water and sanitation have reinforced the need to use the HR lens to properly address inequalities and discrimination. The COVID-19 crisis has raised many questions related to the HRtWS. The pandemic has exposed inequalities, particularly regarding access to water for handwashing, an acute expression of what can be expected of emergency situations such as this sanitary emergency. Climate change exacerbates inequalities and injustice when the HR framework is not mobilized for prevention, mitigation and adaptation.

This emblematic year of 2020 calls for taking stock and prospecting the future in terms of the realization of the HRtWS. The 12 years of two mandates of the SRs have provided a picture of the HR challenges related to safe drinking water and sanitation and provide a historic window into the implementation of those rights.

This paper adopts the perspective to reflect on these 12 years of work by the SRs, seeking to learn from their activities, particularly the thematic reports issued, and the country visits undertaken. The paper is structured in three parts.

Section 2 and

Section 3 analyse the content of the thematic reports and the reports of the official visits to countries.

Section 4 highlights important elements that need further analysis for the development of the content of the HRtWS. As an introduction to the Special Issue on the HRtWS, the paper refers to other published papers in this volume to illustrate some of the arguments built herein.

2. Learning from the Thematic Reports

All the Special Procedures mandate-holders are requested by the UN HRC to submit annual reports that include an exploration of relevant themes related to the subject of the mandate. Some mandate-holders are also requested to present another annual report to the UNGA Third Committee. The thematic reports discuss issues that can be instrumental for the realization of the HR that fall within the scope of each mandate and can cover theoretical and legal analysis, clarification of concepts, empirical trends and developments, concerns related to the neglect or barriers for the realization of the right(s). The thematic reports present recommendations for States and other actors, whose actions (or inactions) contribute to respecting, protecting and/or fulfilling the human right(s) in question.

The two SRs on the HRtWS have published 22 thematic reports (

Appendix A (3)), covering a range of themes. Aiming at gaining a clearer understanding of the scope and analytical approach of each thematic report, a three-axes framework [

5] is used in the present paper (see

Table 1) to categorize and structure our analysis of the reports, and encompasses three dimensions, namely, drivers, policies, and people.

For the first axis—drivers—the departure point is that structural determinants across the development of modern society, even in developed countries, have produced the exclusion of part of its population from enjoying the HRtWS. This excluded population coincides with groups excluded from various other economic, social, and cultural HR, such as health, education, and housing. Some of these groups are often also excluded from access to justice, from the right to be elected, from choosing their political representatives, and from enjoying freedom of speech, and are often the most vulnerable to the impacts of environmental change. The reports classified under this axis address those structural determinants that can be considered root causes of situations of violation or realization of the HRtWS, and that often cannot be addressed exclusively through efforts by the water and sanitation sector.

The second axis—policies—addresses how the (lack of) realization of the HRtWS is explained by the practices of several agents of the water and sanitation sector. Those practices form a complex picture, since the sector agents and their approaches are multiple, diverse and nuanced, just as the related culture of each region, country and local context are. However, it is possible to explore to what extent some elements that comprise a public policy, such as regulation of water and sanitation services, are aligned with the framework of the HRtWS and how each element could benefit from this alignment.

Finally, the third axis—people—encompasses the identification of groups particularly affected in their enjoyment of the HRtWS. The country missions, discussed in

Section 3 of this paper, show that this issue is a complex and variable mosaic, strongly influenced by the socioeconomic and political context. If in countries of very low development level this exclusion is more general; in countries of medium level of development, a pattern of discrimination in relation to particular groups is clearer. In developed countries, the exclusionary pattern is evident, such as can be seen with the homeless (

Appendix A (4)), with migrants (

Appendix A (5)), and with original communities (

Appendix A (6)).

The application of the three-dimensional framework, as shown in

Table 1, reveals some prominence of issues related to policies, representing more than half of the total reports. Each report has been placed in the table under the axis that best describes the intention of the report. However, some of the reports cover more than one dimension, such as the report on nondiscrimination and equality in the post-2015 agenda, which at the same time dealt with policies to be encouraged under Agenda 2030 (which became a driver after the SDG Declaration was approved) and population groups to be prioritized in the Agenda; another example is the report on affordability of water and sanitation services, which associates policies to promote affordable services and identifies the groupsmost affected by unaffordable services.

3. Learning from the Country Visit Reports

Invited by the countries, the SRs have conducted two or three visits per year. After each visit, a report with an analysis of the situation in the country, with recommendations, is presented to the UN HRC and made available on the website of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Twenty-three countries were visited during the twelve years of the two mandates. In alphabetical order (with the year of the publication of the country report in brackets): Bangladesh (2010), Botswana (2016), Brazil (2014), Costa Rica (2009), Egypt (2010), El Salvador (2016), India (2018), Japan (2011), Jordan (2014), Kiribati (2013), Lesotho (2019), Malaysia (2019), Mexico (2017), Mongolia (2018), Namibia (2012), Portugal (2017), Senegal (2012), Slovenia (2011), Tajikistan (2016), Thailand (2013), Tuvalu (2013), the United States of America (2011, and Uruguay (2012)) were visited (see detailed information in the

Supplementary Materials). In addition, follow-up on the level of implementation of previous recommendations, without a visit, has been carried out during 2019 for Botswana, El Salvador, Portugal, and Tajikistan, and during 2020 for India, Mexico and Mongolia. All reports are publicly available on the Mandate website [

6].

We have analysed the recommendations arising from the visits as a way of understanding common challenges in the recognition and realization of the HRtWS across countries, and as a way of identifying topics that require further attention.

To facilitate the analysis, the recommendations included in the country reports were extracted and included in a database. Each recommendation was tagged against a number of categories according to its content. For a basic characterization, the following tags were included: (i) principles of human rights, (ii) normative criteria of the human rights to water and sanitation, (iii) the subsector of analysis (water, sanitation, both), (iv) specific target groups and (v) specific settings mentioned. In addition, the content of the recommendation was classified into the core water governance function referred to by Jiménez et al. [

7], and as summarized in

Table 2. For the countries where a follow-up report had been carried out, the level of implementation of each recommendation was also recorded.

3.1. Basic Characteristics of the Recommendations of the Country Reports

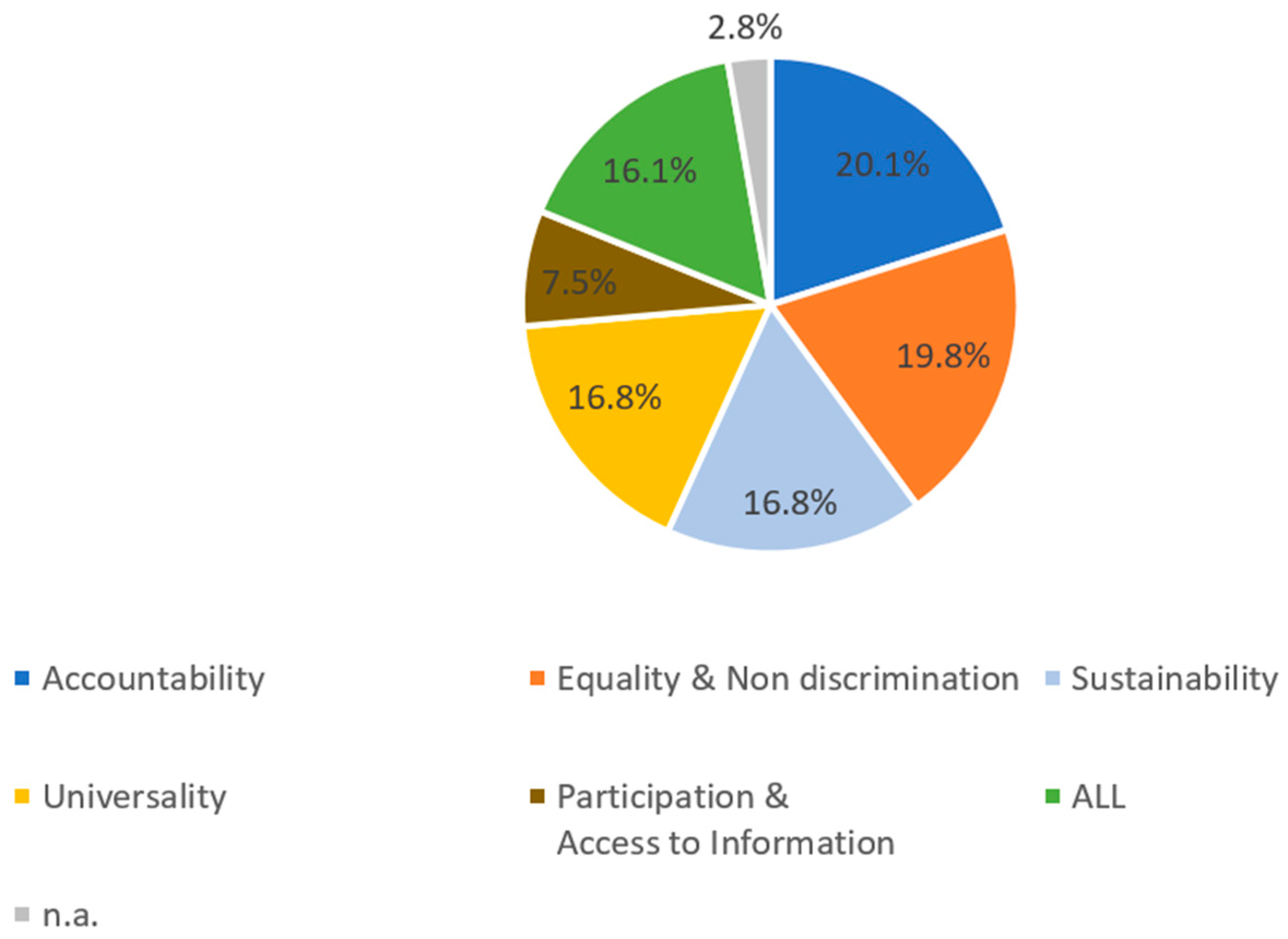

In total, 398 different recommendations were identified and analysed. Each country report contains 17 recommendations on average, from a minimum of 11 to a maximum of 25. When analysing the content of the recommendations linked to the principles of human rights (

Figure 1) it can be observed a fairly equal distribution across the different principles,. However, explicit mentions to universality, equality and nondiscrimination, accountability (through e.g., enacting new policies and laws and reinforcing regulation), and sustainability of services are frequent. It is important to note however, that as principles are general and quite interrelated, the interpretation of the most prominent principle addressed in the recommendation is not always straightforward.

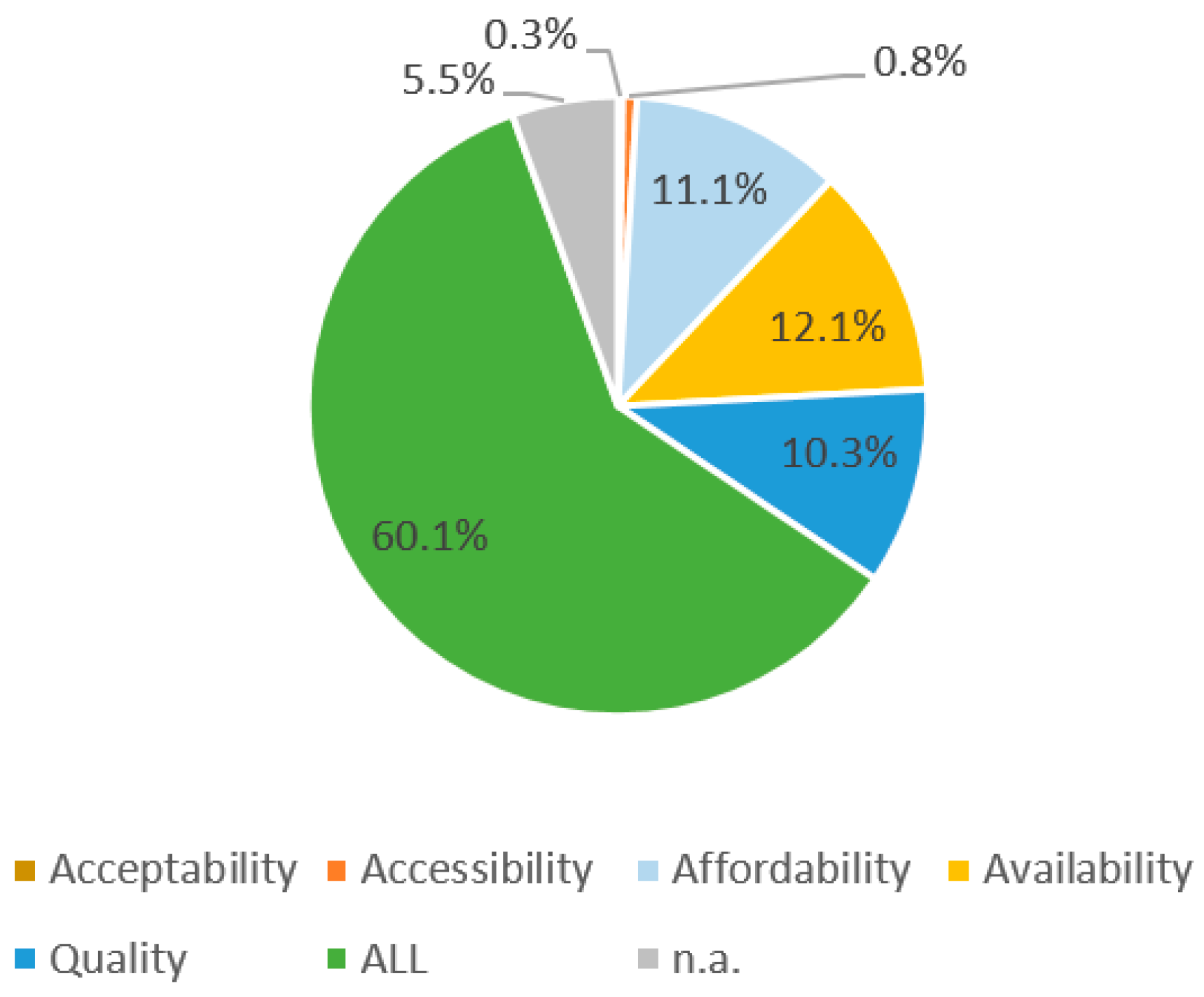

When it comes to the normative criteria (

Figure 2), the distribution is less equal. From one end, almost 60% of the recommendations apply to all normative criteria. Availability of services, affordability and quality (particularly regarding drinking water) are frequently mentioned. Acceptability and accessibility of services do not receive many specific recommendations.

3.2. The Water-Sanitation Distribution, and Links to Other Sectors

Sixty-five percent (65%) of the recommendations address both water and sanitation, with 14% only addressing water, and 12% only addressing sanitation (

Figure 3). The majority of the recommendations only addressing water focus on water quality. When it comes to sanitation, specific recommendations focus on availability of the service, through additional funding and the creation of adequate service delivery models. Climate change only received specific attention in 2% of the recommendations. Specific recommendations addressing the linkages between water services and water resources management were negligible (only appearing a couple of times) and there were only three specific mentions of transboundary water issues. Similarly, there are only a few occurrences of recommendations linked to other sectors (e.g., agriculture, tourism). The impact of the private sector on the enjoyment of the HRtWS was explicitly mentioned in under 1% of recommendations; however five other recommendations relate to the impact of megaprojects on the enjoyment of the HRtWS, which relate partially to the private sector.

3.3. References to Specific Groups and Settings

In 69 out of 398 recommendations (17%) there was reference to one or more specific groups or settings. Generic expressions, such as poor or marginalized are not included in these figures. In terms of groups (

Figure 4), indigenous and ethnic groups were the most mentioned (18); followed by allusions to gender issues (8), displaced people (including refugees, evicted, or stateless people) (8) and people living in homelessness (6). Among other groups mentioned by the SRs are the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes in India; people with disabilities; manual scavengers, vendors and street workers. In terms of settings that were focused on by the SRs (

Figure 5), schools are mentioned in nine recommendations, occasionally together with health centres, and prisons. Informal areas (including urban slums) and rural areas also received specific mentions in recommendations.

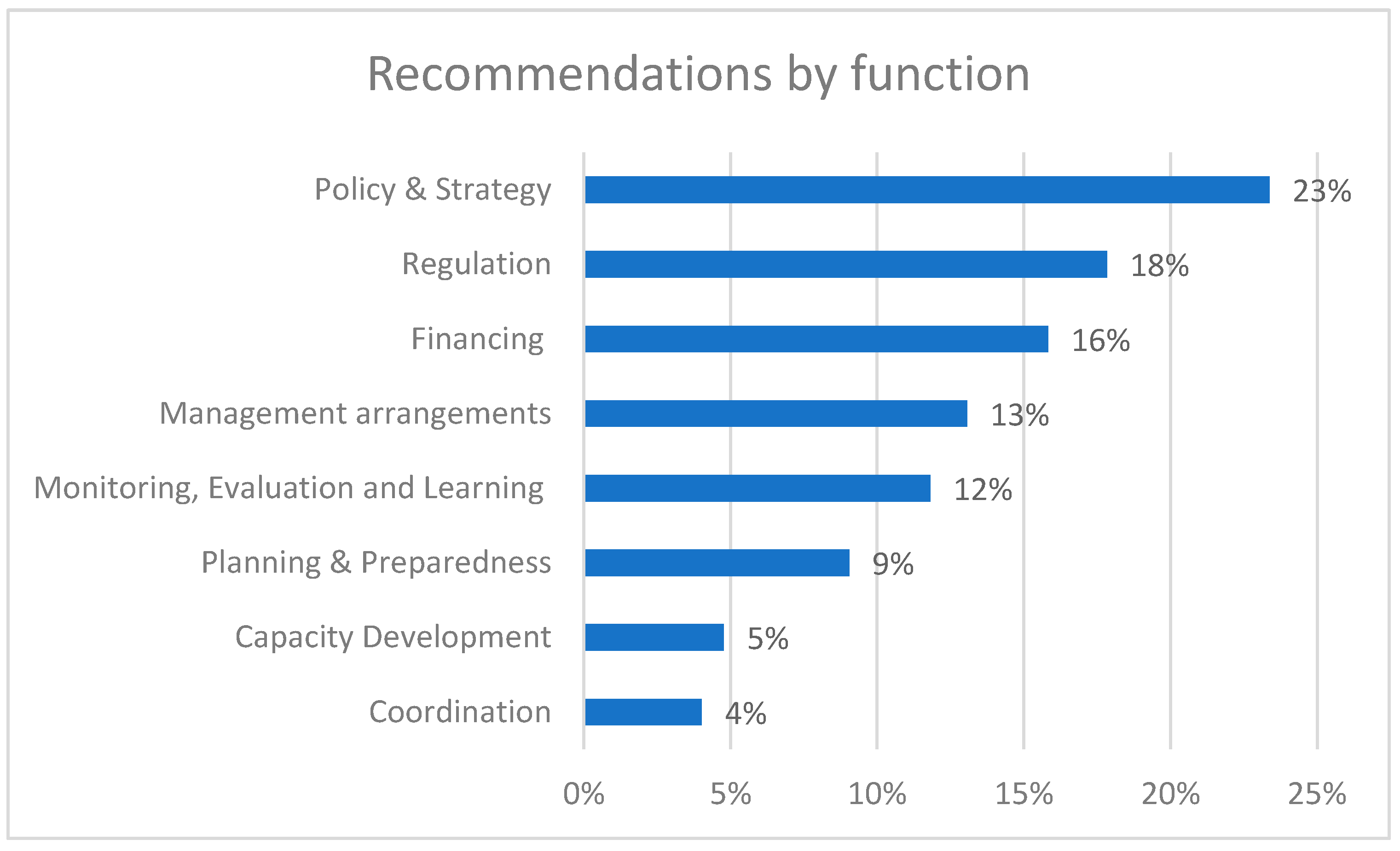

3.4. The Content of the Recommendations by Core Water Governance Function

In terms of the relevant core water governance function (see

Table 2) that each recommendation addresses, policy and strategy, regulation and financing were found to be receive the biggest attention from the SRs (

Figure 6).

From a policy and strategy perspective, the recommendations focused on the following aspects:

Signing and/or ratifying the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and other international texts that recognize HR at large, such as the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and/or the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

Adopting legal provisions that recognize the HRtWS at the national level; by means of constitutional amendments and/or development of national water and sanitation laws and policies which include the recognition of the rights; aiming towards ensuring that these rights are justiciable in national courts.

Strengthening and recognizing other related rights at the national level, and supporting implementation: such as the right to participation, the right to information, and in general allowing for a wider civic space. This is particularly important, since, as shown by Schiel et al. in this Special Issue [

8], the constitutional recognition of the human right to water brings tangible benefits when it is foregrounded in democratic governance.

At a more specific level, there are also recommendations directed to the inclusion of specific aspects of the HRtWS in existing policies, such as more attention to specific subsectors (e.g., sanitation), settings (e.g., schools) or specific groups (e.g., indigenous peoples).

From the perspective of regulation, the general recommendations can be summarized as follows:

Clarify the roles and responsibilities of institutional actors in the water and sanitation sector, both vertically, among central, state, and local governments; and horizontally, among entities within the different tiers of government. This would avoid duplication of roles and increase accountability towards citizens.

Establish an independent regulatory mechanism with adequate financial and human resources to monitor the implementation of the HRtWS, including all the normative content of those rights, and including for services provided through both formal and informal actors.

When more specific, the recommendations on regulation were targeted to:

Regulation of water quality, through the establishment and reinforcement of existing institutions, adoption of standards, and improvement of monitoring capabilities.

Regulation linked to affordability, through the setup and control of social tariffs, as well as procedures for disconnections. This has proven to be very relevant for countries of all economic statuses, as discussed in the paper by Lopes in this Special Issue [

9], which discusses how water service providers dealt with affordability issues in Portugal in the midst of the 2008–2014 economic crisis.

From the financing perspective, the recommendations could be classified into four different categories:

Recommendations aimed at universality of the service, ensuring that the service can reach all; some recommendations include specific suggestions, such as the use of targeted budget for specific areas (e.g., rural areas).

Recommendations aimed at ensuring the sustainability of the service, by suggesting adequate funding for operation and maintenance, and ensuring sufficient means for the service providers and technical assistance institutions, which contribute to the sustainability of services.

Recommendations aimed at ensuring nondiscrimination in financial allocations, either targeted to raise attention towards specific groups (e.g., indigenous, ethnic minorities, homeless, refugees), or specific settings and locations (prisons, schools, public spaces, etc.).

Recommendations directly targeted to external support agencies (ESAs)-and aid actors. These recommendations are mainly calling for countries and ESAs to fully integrate the HR perspective in development assistance, as well as increasing alignment and coordination with the recipient countries.

From the management arrangements for service delivery perspective, the recommendations can be summarized as follows:

Recommendations aimed at increasing availability of services, either in underserved areas or for discriminated against populations, through setting up of specific service delivery models. In these recommendations the SRs have been very specific and highlighted aspects related to the country context. Thirty percent (30%) of all recommendations that mention specific areas (e.g., schools, places of detention) or groups (e.g., indigenous, ethnic minorities, homeless, refugees) were categorized under this core water governance function.

From the 49 times that sanitation could be identified in the recommendations, one third of the occurrences are related to management arrangements. The recommendations urge the governments to include specific measures to ensure sustainability of sanitation services, as well as ensure nondiscrimination in access to services for certain groups. In five countries, specific recommendations were made for the adequate consideration of menstrual hygiene management aspects, particularly in schools and health centres.

For monitoring, evaluation and learning, one third of all recommendations speak to the need to improve monitoring of water quality. In addition, there are recommendations to perform studies aimed at understanding the situation of the underserved population. In this volume, Queiroz et al. [

10] present an approach to monitor inequalities in access, which offers solutions in this direction. In addition, improvements in the measurement of affordability are also requested by the SR. Megaprojects are mentioned in five recommendations, and in all cases the recommendations relate to evaluating and monitoring the potential or ongoing impact of these projects on HR fulfilment.

For planning and preparedness, within the recommendations included for planning, one third relate to the quality of the planning processes—the SRs call for wider engagement, participation and increased accountability to people in the water and sanitation planning processes, not least by including marginalized groups. Sanitation is the focus of some of the recommendations, where the SRs highlight the need for specific plans to bridge the access gap. In terms of preparedness, few recommendations are provided. Half of the mentions of climate aspects by the SR relate to planning, mostly focused on adaptation to climate change, which is an area at the interface of several SR mandates.

For capacity development, the recommendations can be classified into two subsets, with two-thirds related to awareness-raising of the population through education and information campaigns, both related to the content of the HRtWS, as well as on the adequate use and costs of water and sanitation. The other third of the recommendations are targeted towards the capacity development of institutions engaged in service delivery at different levels. Of particular importance is the support to the role of local government, often having the delegated responsibility to ensure the provision of services, as presented by Carrard et al. in this Special Issue [

11].

Coordination receives the least attention from the SRs compared to other core water governance functions. The recommendations are aimed at more active cooperation and information sharing within the governments to ensure effective implementation of policies and plans, as well as supporting the continuous dialogue and interaction with different segments of the population in relation to the services.

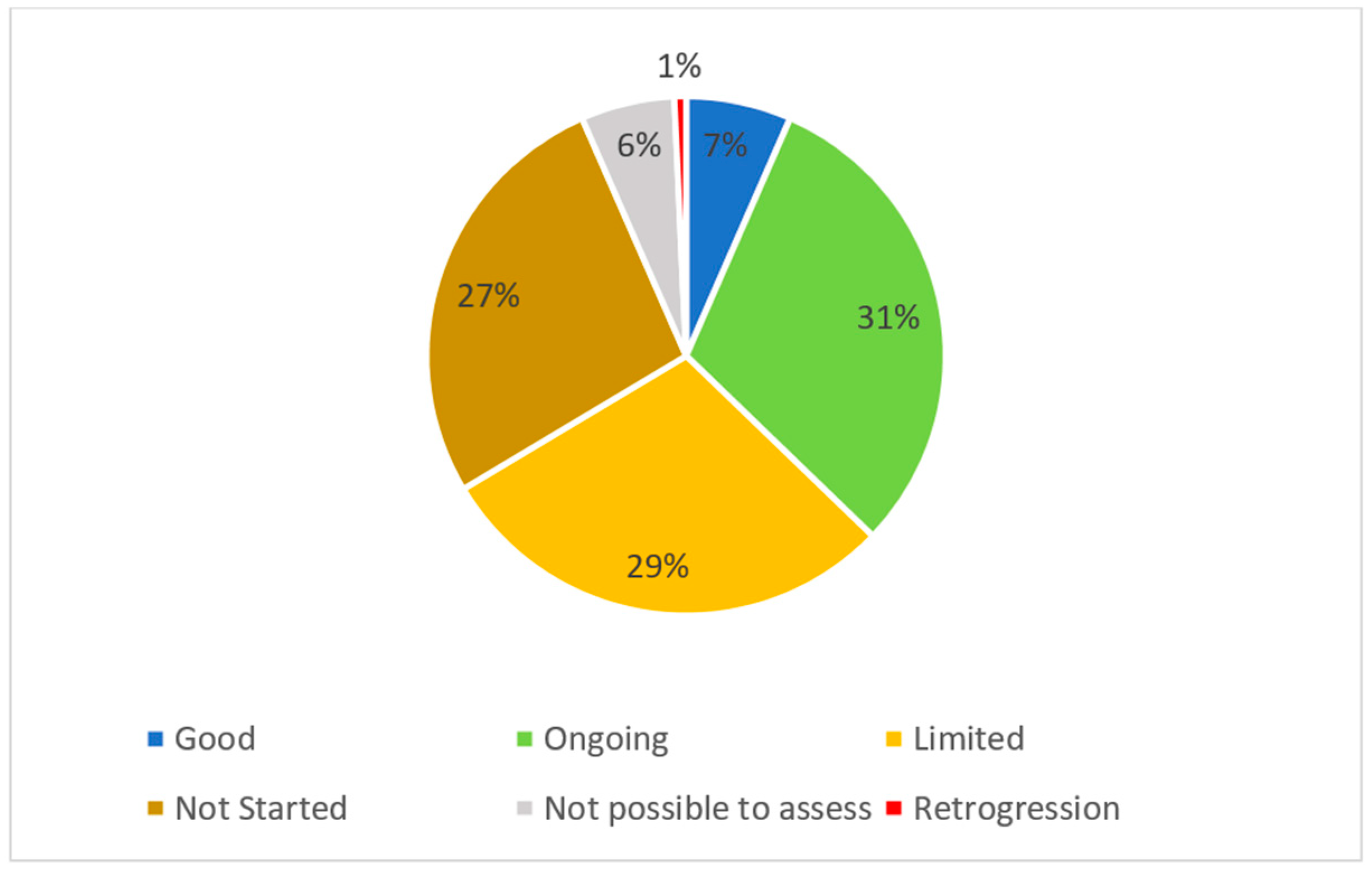

3.5. Status of Progress

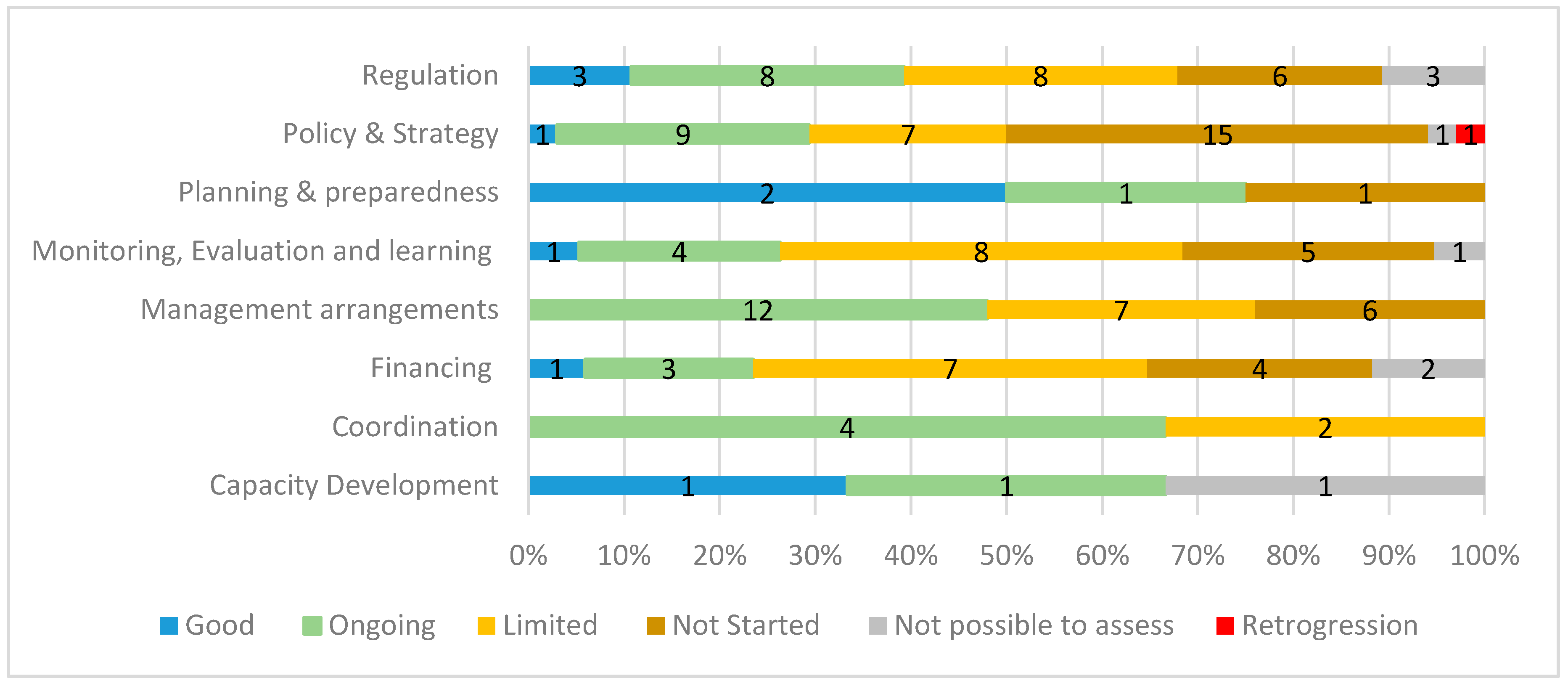

Seven country visits have been followed up on, corresponding to all the visits undertaken by the second SR, except the two most recent, where an insufficient period of time has elapsed since the visit to allow for a meaningful follow-up exercise. In monitoring of the status of progress in implementing the recommendations, the follow-up exercise found that only 7% of recommendations were rated as having good progress; 31% were found to be ongoing; and over 50% were not positively assessed, due to one of the following reasons: limited progress, not being started, or being in retrogression. Six percent were not assessable due to lack of information (

Figure 7)

When looking at the level of implementation by governance function (

Figure 8), satisfactory progress (Good or Ongoing rating) can be mostly found in aspects related to Planning, Coordination and Capacity Development. However, these functions include a relatively low number of recommendations. Management arrangements issues show relatively good progress, with almost half of the recommendations rated as ongoing. The recommendations that need higher political will and more structural changes, such as policy and legal issues, regulation, changes in national monitoring and financing, all score rather poorly. The governance function where recommendations were found to have the lowest level of implementation is financing, where only 25% of the recommendations evaluated were at a satisfactory level of progress. From these findings, it seems that the recommendations of the SRs are not enough to trigger the needed change in the institutional environment and financial structure of the national water and sanitation sectors. However, it is also important to note that the review of progress was done in the seven countries between two and three years after the first report, so a part of this lack of progress might be explained by the lack of time to implement those structural changes, that in some cases depend on legislative approval. At the same time, the momentum generated by the visit of the SR can be lost as years pass, unless an active civil society is able to keep the issues prominent in the national agenda. More reviews of the progress of recommendation implementation, particularly in countries which have had more time to implement the recommendations (e.g., five years or more), are needed to complete the analysis.

4. Looking into the Future

4.1. Realizing the Potential of Country Visits

The analysis of the country visits highlights (with the perspective of 12 years) a few aspects to consider moving forward. The HRtWS is seen as inextricably linked to the recognition of other rights, as well as to the existence of civic space in general. This points towards the relevance of further discussion about the interdependency of rights when it comes to implementation, and how the coordinated efforts of SRs can be useful in this matter. This is relevant when considering the interaction between water resources and water and sanitation services, a topic which does not appear often in the country report recommendations. The fact that water resources management crosses different mandates, particularly those with an environmental focus, constrains a more prominent focus on it under the water and sanitation mandate. This creates some fragmentation in the analysis, as water services and water resources are interlinked, with the linkages seriously affected by climate change. This speaks again to how the different mandates can be mutually reinforcing when making recommendations to the countries. A similar situation happens with private sector activities, which also fall within various mandates. Simultaneously, the private sector at large has a responsibility in the fulfilment of the rights, and can also violate the rights through impacts from industrial activities, as the thematic report on mega-projects has shown.

Specific recommendations for duty bearers by delegation, such as service providers, are not very prominent in the country reports. The reports are directed to national governments, as main duty bearers. Given the fundamental role of delegated service providers in the practical implementation of the rights, a more explicit analysis of their role, with recommendations directed towards them would be very beneficial, both for public and private service providers, and if not provided by the SR, through further research and analysis instead.

Finally, the recent initiative to follow up on previous SR missions is important to understand the impact of SR visits, and to understand the difficulties for countries in moving forward in certain aspects of the rights, and can provide important lessons moving forward, both more generally and for other countries to learn from.

4.2. Some Pending Analytical Explorations

The joint analysis of the thematic reports and the reports of the country visits highlights that a substantial number of topics of relevance at country level have been addressed over the last 12 years. At the same time, the analysis suggests that other topics might also be among the priorities, but could not be carried out, due to lack of time or prioritization. We believe that exploration of the additional topics outlined below has the potential to contribute to the advancement of the HRtWS.

The UN and the HRtWS

Considering the adoption of several resolutions by UN bodies, recognizing and clarifying the meaning of the HRtWS, a close alignment of all the UN system working on issues related to water with the HRtWS framework would be expected. However, some initial and nonsystematic observations have shown that the behaviour of some of those bodies has not necessarily been in that direction.

A first discussion on this issue can be raised in relation to SDGs monitoring, where the formulation of indicators to monitor both SDGs targets 6.1 and 6.2 has missed part of the HR content reflected in the respective targets. The same gap can be identified in the process of operationalizing such indicators in global monitoring (

Appendix A (8)).

Another useful approach could be to map the relevant strategies, plans and activities undertaken by UN agencies actively working on water and sanitation issues and identify the level of alignment to the HRtWS framework. As an example, this exercise was performed for assessing the development cooperation policies and programmes of United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), with findings showing good performance in terms of using the HRtWS framework directly or indirectly in their development cooperation activities. However, there is room for improvement and strengthening the integration of this framework into the organization, particularly in field work, as discussed in the Development Cooperation Thematic Report [

14].

An important body to be included in this analysis is UN-Water, a coordinating body that encompasses 32 UN agencies, programmes, and other UN entities “dealing with water-related issues” (

Appendix A (9)), together with partners and donors. When addressing water and sanitation, it is relevant to assess to what extent the HRtWS have informed both theoretically and empirically the coordinating role and the external communications of this body. One important product of UN-Water is the annual World Water Development Reports (WWDRs). The theme of the 2019 report focussed on “Leaving no one behind” and its content is truly aligned with the HRtWS framework. Apart from this theme, it would be useful to assess how the HRtWS framework has been reflected in other annual WWDRs.

Additionally, it would be relevant to also assess how the HRtWS is addressed by treaty bodies of the HRC, as well as by procedures that evaluate a country’s performance in terms of HR compliance, such as the Universal Periodic Review.

Climate change

Climate change, as well as other global environmental issues, are located at an interface of different Special Procedures mandates. Adapting and building resilience to the impacts of climate change requires a holistic and adaptive approach to water resources management, with full consideration of the linkages with water and sanitation services, factoring in anticipated future changes in availability and quality of water resources.

Perhaps the multiple dimensions of climate change explain the low level of its representation in recommendations arising from country missions undertaken by the SRs. In El Salvador, which was facing a severe drought during the visit of the SR, a recommendation was issued to “strengthen the national strategy to cope with climate change, which should include the establishment of an effective mechanism to provide a timely response to future droughts and their impact on the most vulnerable population, including the rural population”. Also, both in Kiribati and in Tuvalu, Small Island Developing States (SIDS) strongly impacted by rising sea levels due to climate change, recommendations included “establishment of legal and institutional framework taking into consideration changing climate and its impacts on water and sanitation” and that adaptation plans put the HRtWS at the centre.

HR is a clearly neglected theme in climate change discourse, and this was evident in the discussions during the Conference of the Parties (COP) 25 held in Madrid in 2019, where particularly the HRtWS were absent in the official negotiations. This silence was highlighted in side events during the COP. Some SRs have issued thematic reports addressing the climate change topic. However, a more focussed approach relating the HRtWS and the climate emergency would fill a knowledge gap and would contribute to supporting States in framing plans and measures to tackle climate change around aspects related to water and sanitation through a HR lens.

A Position Paper associating climate change and the HRtWS was commissioned by the first SR and gave insightful views on legal obligations, impacts of climate change on the HRtWS, and integration of the HRtWS in climate policy-making, including on issues related to mitigation and adaptation (

Appendix A (10)).This can provide an initial basis for a more in-depth, analytical and political approach.

In any development of this discussion from the HRtWS perspective, it will be necessary to bear in mind that climate change adds an additional layer of vulnerability to those already living with several layers of vulnerability.

Public provision of water and sanitation services

The current SR has recently issued a report on the privatization of water and sanitation services and the associated risks of HR violations, based on the need to highlight such a theme. The relevance to explore the theme is grounded on the usual silence of the HRtWS community around it and the common idea of “neutrality” or “agnosticism” regarding different types of service provision.

The report does not aim to compare the private and public provision of water and sanitation services, but to address specific risks of the former. While the report does not assess the public provision of services, it is highlighted that this type of provision also incurs HR risks, but of a different nature, given the particularities of the public sector.

Against this context, and considering that approximately 90% of water and sanitation services worldwide are delivered by public (or community-based) providers [

15] (

Appendix A (11)), an assessment of the challenges public providers face in realizing the HRtWS would be relevant for both the water and the HR community. This would give an opportunity to reflect on ways to align the framework of public policies and management of water services with the HRtWS framework. In addition, the analysis could cover issues such as how to improve public management, the strengths and weaknesses of different organizational models, the balance between economic sustainability and affordability, political influences, effects of corruption and cronyism, and specific features of accountability of service providers, among others.

Drinking Water Quality Control and Surveillance

Quality and safety of drinking water is one of the elements of the normative content of the human right to water. It is usually taken for granted that this is the most objective of the five elements of the normative content and often the World Health Organisation (WHO) Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality [

16] are considered a sufficient approach upon which to infer national water quality standards and control and surveillance approaches.

Drinking water quality has been reflected in a series of recommendations from the country visits, focussing on the need to update the national water quality standards (Lesotho, Mexico, Mongolia), to strengthen water quality surveillance by health authorities (Botswana, El Salvador, Kiribati, Lesotho, Malaysia, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Thailand), to monitor specific contaminants (arsenic in Bangladesh, agrochemical pollutants in El Salvador, pesticides in Mexico and Malaysia) or to ensure adequate access to information (India, Jordan, Mongolia and Portugal).

However, although the predominant background for this issue has allowed assessments and guidance on different aspects of water quality, a lack of proper translation of some definitions to specific situations and use of the HR framework is observed.

The complementary roles of providers—responsible for water quality control—and health authorities—responsible for water quality surveillance and auditing quality control—is a key issue that deserves more clarity under the HRtWS framework, including under the principle of accountability. The role of regulators in this regard is also a complementary element of this institutional landscape that needs further clarity.

Another necessary discussion relates to which parameters should be prioritized in monitoring activities in each context, considering that the whole list of water quality parameters set up in the WHO guidelines could be sometimes challenging to immediately implement. Hence, to clarify this issue from the perspective of the progressive realization of the HRtWS would be very useful guidance.

A topic that can be approached under this theme is how to translate the monitoring of water quality under SDGs target 6.1 and the definition “free from contamination”, translated as meeting standards related to faecal contamination and contamination by priority chemicals. Particularly, priority chemical contaminants, defined as arsenic and fluoride [

17], may not be relevant or “priority” in many contexts that might require a different focus. A clarification of these issues considering the health risks of the most disadvantaged groups, who already face other layers of health vulnerabilities, would be extremely relevant from a HR approach.

Other key approaches would be how to translate drinking water quality information into an accessible language to communicate to right holders; drinking water monitoring of individual water supply solutions (issue raised during the missions to Portugal and the USA); and drinking water monitoring in institutions (school, health institutions, detentions centres, asylums, refugee camps, etc.).

Rural sanitation

When compared with the areas of urban water, rural water and urban sanitation, rural sanitation is clearly the one that has been most left behind in the latest years and decades. This concern has drawn the attention of many stakeholders and led to initiatives such as the Call for Action launched by Plan International UK, SNV, UNICEF, WaterAid, the World Bank and the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) in late 2019, which calls for a step up in ambitions and investments, and to use the agreed principles in their programmes: (

Appendix A (12)).

From the HR point of view, it is expected, firstly, to highlight this neglect, and, secondly, to give guidance under the HRtWS framework.

A number of issues could be raised when applying the HRtWS framework, including cultural acceptability of different technical solutions, which can explain failures of initiatives; limitations of standard solutions—one-size-fits-all—both at the technological and at the governance levels; sanitation access as an essential component of adaptation strategies against climate change; stigma and shaming associated with behavioural change strategies, such as Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS); possible distortions in terms of HR compliance of large scale and ambitious programmes (

Appendix A (13)); participatory processes for technology selection and management; affordability and the role of States in subsidizing households; how self-supply costs and the impact on affordability compare with those costs usually incurred by urban sanitation interventions; the balance between self-supply and the access of people facing vulnerability, such as the elderly, people living with disabilities, and children; and reconciliation between self-supply solutions and the State obligations to progressively realize the HRtWS using the maximum available resources.

Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples encompass a diversity of cultural and social traditions and these features have implications for how water and sanitation services are best delivered, and how the State meets its HR obligations.

In several country missions, particular requirements for the enjoyment of the HRtWS by indigenous groups were highlighted. Recommendations include: development of legislation ensuring the HRtWS are protected and implemented (El Salvador); improvement of regulatory and policy frameworks on access to information, participation and prior, free and informed consent (Mexico); development of strategic plans for indigenous peoples living in traditional reserves (Costa Rica); and necessary legal action for unrecognized and terminated tribes to realize their rights to water and sanitation, and ensuring prior and informed consent regarding activities affecting access to water by indigenous groups (USA).

The situation of indigenous peoples has also been recognized and explored by other Special Procedures mandate-holders. The SR on the right to housing published a report in 2019 on the right to housing of indigenous peoples. The SR covers, among other issues, the relationship between the right to housing and the rights of indigenous peoples; situations of reserves and reservations as well as of nomadic and seminomadic peoples; effects of climate change; and specific legislation, policies and strategies [

18].

The SR on the rights of indigenous peoples published a report on “economic, social and cultural rights of indigenous peoples in the post-2015 development framework” [

19]. In the report, the SR acknowledges that “[i]n nearly all of the countries in which they live, indigenous peoples fare worse than nonindigenous sectors of the population in terms of their development, including levels of poverty, education, health, unemployment, housing conditions, clean water and sanitation.”. She also recommended that “[t]he processes to define, implement and monitor the SDGs should be used as a vehicle to address the aspirations of indigenous peoples for self-determined development, and to achieve equality in development outcomes. This will require the full and effective participation of indigenous peoples in the definition, implementation and monitoring of the goals at both the international and national levels, including the establishment of regular mechanisms for consultation and participation”.

A specific analysis focussing on the HRtWS for indigenous peoples would be relevant, since it may cover issues such as the confluences between international law related to the HRtWS and the HR of indigenous peoples; specific features of the access to water and sanitation by indigenous groups [

20] and how to ensure respect, protection and fulfilment of their rights in legislation and policies; acceptability of water and sanitation solutions and how acceptability relates to cultural patterns and behaviours of different groups, including reasons for past project failures due to inappropriate technology or approaches; the traditional use of surface water and groundwater (see article in this volume by Grönwall and Danert [

21]) and how the HRtWS framework applies in self-supply situations, as well as how states meet their HR obligations in these contexts; impacts on the access to water by indigenous peoples due to megaprojects and other interventions, and how free, prior and informed consent must be applied; HR realization in groups not willing to be contacted and how to reconcile the HRtWS with the right to self-determination.

Sanitation workers

There are different types of sanitation workers, ranging from those with formal jobs, unionized, and provided with the necessary individual protective equipment, to manual scavengers invariably working in very unsafe environments and facing stigma and high risks to their life and health.

Sanitation workers might be a group doubly affected in their enjoyment of the right to water or the right to sanitation, due to both a lack of access to services and being exposed to unacceptably high risks to their life and health in their work due to the failure of states to meet their obligations related to the right to sanitation.

A recommendation that emerged from the visit to India was to “establish a monitoring system to follow the process of emptying pit latrines under the national programmes, in order to control possible trends of increases in manual scavenging practices, ensuring that this practice is not carried out in a caste-discriminatory manner”. This recommendation is a symbolic demonstration of the need to infuse a HR approach in faecal sludge management.

A recent publication by the World Bank, the International Labour Organization (ILO), WaterAid and the WHO highlights issues related to health, safety, and dignity of sanitation workers, including literature review, case studies and recommendations [

22]. This publication has the ability to raise attention to the problem and is a relevant initial assessment. However, the situation of sanitation workers would benefit from a full HR assessment, focussing mainly on those individuals working in unsafe conditions.

The emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic is a recent situation that has unveiled the significant health risks that sanitation workers are exposed to, in this case a clear increased risk in relation to other workers. The application of the HRtWS framework to this situation would highlight the need for a careful focus on the due protection of these workers.

Questions such as how the HRtWS could contribute to elevating the standard of this work; on the intersectionality of stigma and discrimination, including caste discrimination; on labour protections from the international law on the workers’ rights; and how protection of these workers was contemplated in Agenda 2030, among other issues, would illuminate this situation under the HR lens.

Capacity development

As outlined in

Table 1, capacity development refers to the processes by which organizations, society and individuals systematically stimulate, develop, strengthen and maintain their capabilities over time, to set and develop their goals and objectives to be able to manage water services and resources sustainably [

26]. Capacity development is also included in the means of implementation of the SDG 6 targets: 6.A explicitly mentions, “By 2030, expand international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries”, and 6.B mentions, “Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management”. Strengthening of local participation requires capacity development, as available evidence suggests [

26]. Capacity development is also one of the building blocks of the Sanitation and Water for All (SWA) global partnership; in addition, “Enhance government leadership of sector planning processes” and “Strengthening and use country systems” are two of the core stakeholder behaviours promoted by SWA that need to be put in place for success.

Capacity development is at the core of the aspects that need to be strengthened for the fulfilment of the HRtWS. So far, the SRs have touched upon the aspect of capacity building, both in thematic and country reports. The Development cooperation report states that “capacity-building is key to ensuring the sustainability of investments” and recommends to “incorporate capacity-building as a priority aspect of development cooperation, ensuring the integration of HR principles and related normative content and the involvement of the main stakeholders directly and indirectly relevant to the adequate provision of services”. This topic has also been mentioned in 5% of the recommendations of the country reports.

However, capacity development remains elusive. While several external support agencies report that this is a priority for them, this is often not translated into actual support to country systems [

27]. The countries themselves often lack proper strategies for sustainable capacity development. At the same time, responsibilities for service provision are decentralized, which puts local stakeholders in a challenging situation: they are duty bearers by delegation, but they don’t have the resources and capacities to fulfil their role.

Hence, further exploration of how capacity development takes place and how the HR framework can shape programmes and interventions on capacity development in the water and sanitation sector has the potential to contribute to strengthening capacity development strategies of national and subnational governments and ESAs alike.

5. Conclusions

The work of 12 years of the SRs for the HRtWS have produced an important body of both conceptual and practical knowledge on the content and the challenges of the HRtWS.

Through the analysis of the 23 country reports, we have synthetized and presented the key recommendations, which mainly relate to policy, regulation and financing aspects of water governance, with accountability and nondiscrimination aspects being of greatest concern for the SRs when visiting countries. The initiative to follow up on the status of the implementation of recommendations arising from previous SR reports shows that implementation takes time to materialize and needs continuous attention. The HRC, as well as civil society and the water and sanitation sector at large, could take greater ownership of the SR reports and be stronger advocates for the implementation of the recommendations in each country, and, in the first instance, could push for the invitation of the SR to the different countries.

The thematic reports have contributed to clarifying important aspects of the interpretation of the HR; at the same time, they have discussed how different drivers affect the HR, the policy dimension of the rights and the needed attention on neglected aspects and population groups who are often left behind. However, there is still much work to do. Other papers in this Special Issue have pointed to the challenges of affordability; monitoring of inequalities; self-supply and groundwater; the role of local government; the complexity of service provision in informality; and analysed how and when the constitutional recognition of the HRtWS can positively impact the realization of the rights. In addition to these, we have raised some important issues that will hopefully attract further attention from water and sanitation sector stakeholders, researchers, and HR practitioners: extraterritorial obligations, including transboundary waters; the UN and the HRtWS; climate change; public provision of water and sanitation services; drinking water quality control and surveillance; rural sanitation; indigenous peoples; sanitation workers; informal settlements; and capacity development.