Interpopulation Variability in Dietary Traits of Invasive Bleak Alburnus alburnus (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) Across the Iberian Peninsula

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

2.2. Field and Laboratory Work

2.3. Data Analyses

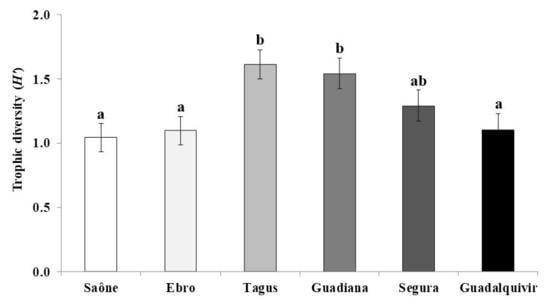

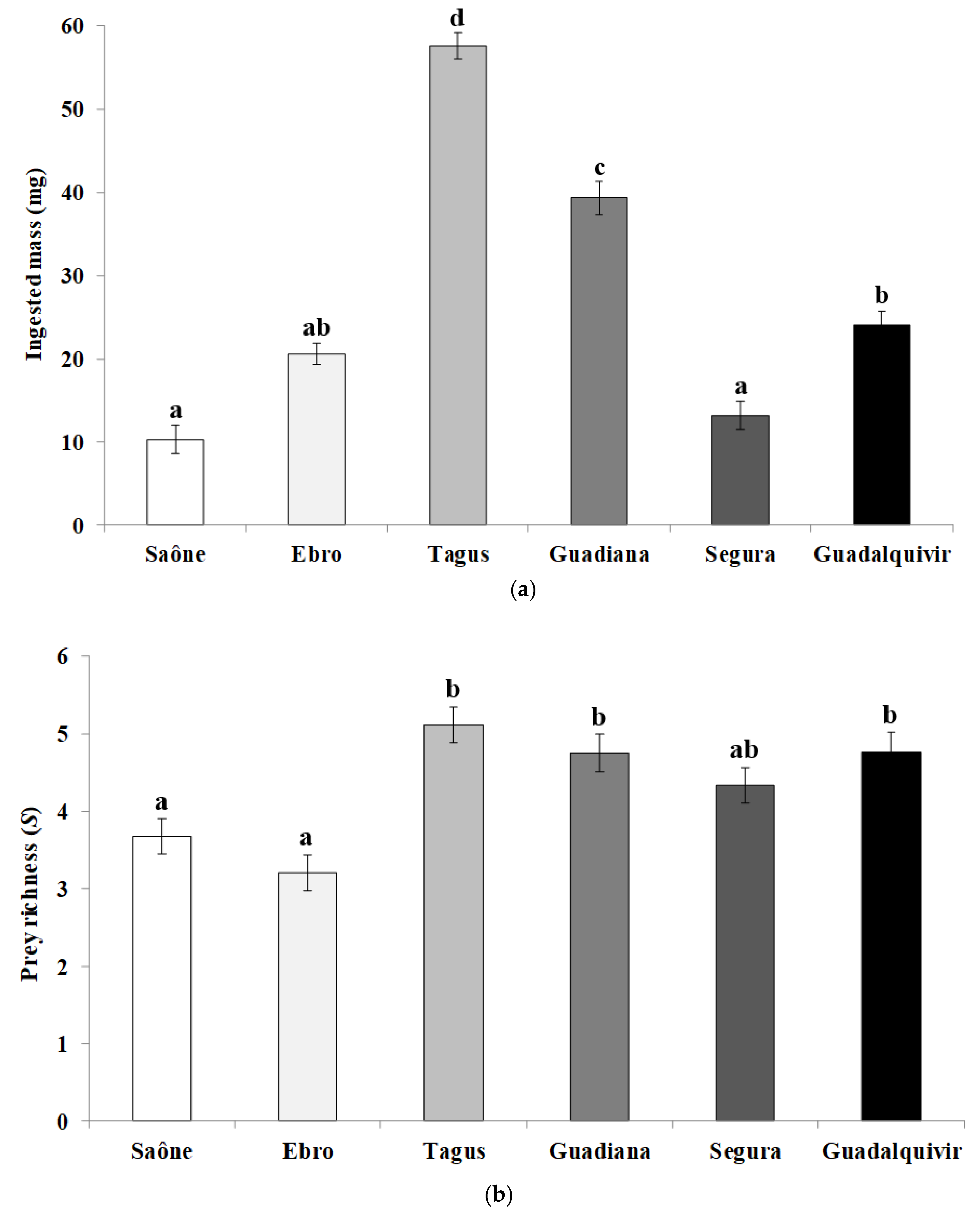

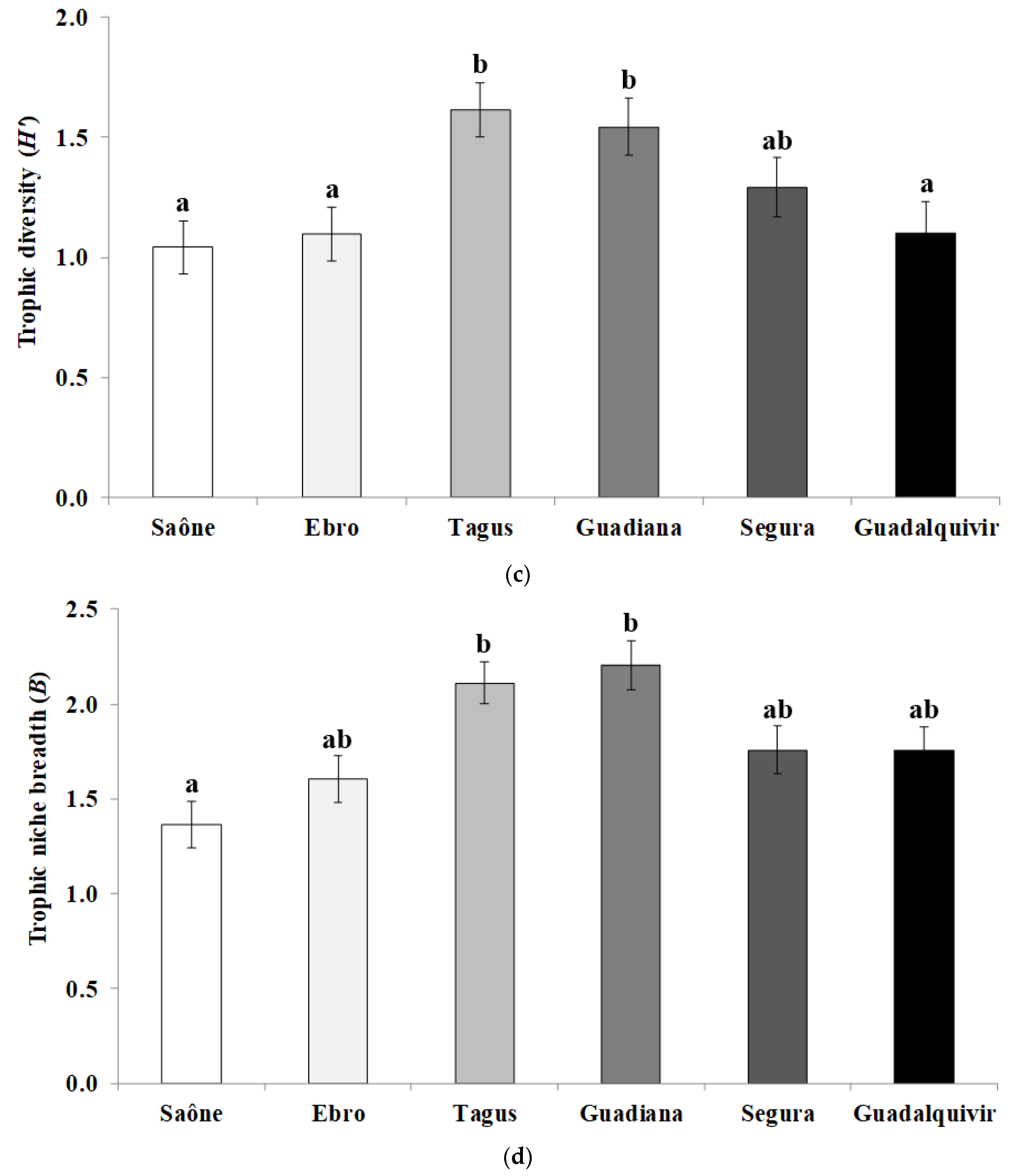

3. Results

4. Discussions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reyjol, Y.; Hugueny, B.; Pont, D.; Bianco, P.G.; Beier, U.; Caiola, N.; Casals, F.; Cowx, I.; Economou, A.; Ferreira, T.; et al. Patterns in species richness and endemism of European freshwater fish. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007, 16, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.; Ribeiro, F.; Leunda, P.M.; Vilizzi, L.; Copp, G.H. Effectiveness of FISK, an invasiveness screening tool for non-native freshwater fishes, to perform risk identification assessments in the Iberian Peninsula. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 1404–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, F.; Leunda, P.M. Non-native fish impacts on Mediterranean freshwater ecosystems: Current knowledge and research needs. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2012, 19, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinni, M.; Horppila, J.; Olin, M.; Ruuhijärvi, J.; Nyberg, K. The food, growth and abundance of five co-existing cyprinids in lake basins of different morphometry and water quality. Aquat. Ecol. 2000, 34, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vašek, M.; Kubečka, J. In situ diel patterns of zooplankton consumption by subadult/adult roach Rutilus rutilus, bream Abramis brama, and bleak Alburnus alburnus. Folia Zool. 2004, 53, 203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, P.; Persat, H.; Feunteun, E.; Allardi, J. Les Poissons d’Eau Douce de France; Biotope Éditions Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle: Paris, France, 2011; ISBN 9782914817691. [Google Scholar]

- Vinyoles, D.; Robalo, J.I.; De Sostoa, A.; Almodóvar, A.; Elvira, B.; Nicola, G.G.; Fernández-Delgado, C.; Santos, C.S.; Doadrio, I.; Sardà-Palomera, F.; et al. Spread of the alien bleak Alburnus alburnus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) in the Iberian Peninsula: The role of reservoirs. Graellsia 2007, 63, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masó, G.; Latorre, D.; Tarkan, A.S.; Vila-Gispert, A.; Almeida, D. Interpopulation plasticity in growth and reproduction of invasive bleak, Alburnus alburnus (Cyprinidae, Actinopterygii), in northeastern Iberian Peninsula. Folia Zool. 2016, 65, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matono, P.; Da Silva, J.; Ilhéu, M. How Does an invasive cyprinid benefit from the hydrological disturbance of Mediterranean temporary streams? Diversity 2018, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amat-Trigo, F.; Torralva, M.; Ruiz-Navarro, A.; Oliva-Paterna, F.J. Colonization and plasticity in population traits of the invasive Alburnus alburnus along a longitudinal river gradient in a Mediterranean river basin. Aquat. Invasions 2019, 14, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.; Grossman, G.D. Utility of direct observational methods for assessing competitive interactions between non-native and native freshwater fishes. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2012, 19, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilizzi, L.; Copp, G.H.; Adamovich, B.; Almeida, D.; Chan, J.; Davison, P.I.; Dembski, S.; Ekmekçi, F.G.; Ferincz, Á.; Forneck, S.C.; et al. A global review and meta-analysis of applications of the freshwater Fish Invasiveness Screening Kit. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2019, 29, 529–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, D.; Masó, G.; Hinckley, A.; Rubio-Gracia, F.; Vila-Gispert, A.; Almeida, D. Interpopulation plasticity in dietary traits of invasive bleak Alburnus alburnus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Iberian fresh waters. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2016, 32, 1252–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.; Fletcher, D.H.; Rangel, C.; García-Berthou, E.; Da Silva, E. Dietary traits of invasive bleak Alburnus alburnus (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) between contrasting habitats in Iberian fresh waters. Hydrobiologia 2017, 795, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, G.H.; Bianco, P.G.; Bogutskaya, N.G.; Eros, T.; Falka, I.; Ferreira, M.T.; Fox, M.G.; Freyhof, J.; Gozlan, R.E.; Grabowska, J.; et al. To be, or not to be, a non-native freshwater fish? J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2005, 21, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.; Almodóvar, A.; Nicola, G.G.; Elvira, B.; Grossman, G.D. Trophic plasticity of invasive juvenile largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides in Iberian streams. Fish. Res. 2012, 113, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavero, M.; García-Berthou, E. Homogenization dynamics and introduction routes of invasive freshwater fish in the Iberian Peninsula. Ecol. Appl. 2006, 16, 2313–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Závorka, L.; Buoro, M.; Cucherousset, J. The negative ecological impacts of a globally introduced species decrease with time since introduction. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 4428–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment France. Available online: http://vigiprevi.meteofrance.com/PREV/V/index.html (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Ministry of Environment Spain. Available online: http://www.aemet.es/es/serviciosclimaticos (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- European Commission. Commission Directive 2014/101/EU of 30 October 2014 amending Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Off. J. Eur. Union-Legis. 2014, 311, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tachet, H.; Richoux, P.; Bournaud, M.; Usseglio-Polatera, P. Invertébrés d’Eau Douce: Systématique, Biologie, Écologie; CNRS Éditions: Paris, France, 2010; ISBN 9782271069450. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz, C.; García-Berthou, E. Food of an endangered cyprinodont (Aphanius iberus): Ontogenetic diet shift and prey electivity. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2007, 78, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.C.D.; Barry, S.J.E.; Ferguson, H.M.; Müller, P. Power analysis for generalized linear mixed models in ecology and evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2018; Available online: http://www.r-project.org (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Latorre, D.; Masó, G.; Hinckley, A.; Verdiell-Cubedo, D.; Tarkan, A.S.; Vila-Gispert, A.; Copp, G.H.; Cucherousset, J.; Da Silva, E.; Fernández-Delgado, C.; et al. Interpopulation variability in growth and reproduction of invasive bleak Alburnus alburnus (Linnaeus, 1758) across the Iberian Peninsula. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2018, 69, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøhn, T.; Terje Sandlund, O.; Amundsen, P.-A.; Primicerio, R. Rapidly changing life history during invasion. Oikos 2004, 106, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Minchin, P.R. Continuum theory revisited: What shape are species responses along ecological gradients? Ecol. Model. 2002, 157, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasith, A.; Resh, V.H. Streams in Mediterranean climate regions: Abiotic influences and biotic responses to predictable seasonal events. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1999, 30, 51–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.; Almodóvar, A.; Nicola, G.G.; Elvira, B. Feeding tactics and body condition of two introduced populations of pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus: Taking advantages of human disturbances? Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2009, 18, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| River: | Saône | Ebro | Tagus | Guadiana | Segura | Guadalquivir | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Category | Oc. | Mass | Oc. | Mass | Oc. | Mass | Oc. | Mass | Oc. | Mass | Oc. | Mass |

| Algae and plant debris | 3 | <1 | 2 | 5 | 29 | 17 | 5 | 3 | 3 | <1 | 8 | 9 |

| Zooplankton a | 50 | 17 | 40 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 1 | <1 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 6 |

| Ephemeroptera and Plecoptera nymphs | 5 | 9 | 33 | 21 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 23 | 7 | 21 | 5 | 12 |

| Odonata nymphs | 1 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 1 | <1 | 1 | 3 |

| Diptera larvae | 69 | 39 | 27 | 15 | 3 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 59 | 31 | 3 | 16 |

| Trichoptera larvae | 6 | 1 | 5 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 15 | 13 | 6 | 11 | 1 | 5 |

| Other benthic invertebrates b | 12 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 53 | 13 | 1 | <1 | 12 | 1 | 71 | 14 |

| Nektonic and neustonic insects c | 1 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 20 | 19 |

| Flying insects d | 3 | <1 | 5 | 8 | 35 | 7 | 61 | 23 | 3 | 19 | – | – |

| Terrestrial arthropods e | 1 | <1 | 1 | <1 | – | – | 1 | 9 | 1 | <1 | 7 | 2 |

| Detritus | 31 | 27 | 25 | 26 | 42 | 24 | 24 | 18 | 31 | 13 | 21 | 14 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Latorre, D.; Masó, G.; Hinckley, A.; Verdiell-Cubedo, D.; Castillo-García, G.; González-Rojas, A.G.; Black-Barbour, E.N.; Vila-Gispert, A.; García-Berthou, E.; Miranda, R.; et al. Interpopulation Variability in Dietary Traits of Invasive Bleak Alburnus alburnus (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) Across the Iberian Peninsula. Water 2020, 12, 2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12082200

Latorre D, Masó G, Hinckley A, Verdiell-Cubedo D, Castillo-García G, González-Rojas AG, Black-Barbour EN, Vila-Gispert A, García-Berthou E, Miranda R, et al. Interpopulation Variability in Dietary Traits of Invasive Bleak Alburnus alburnus (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) Across the Iberian Peninsula. Water. 2020; 12(8):2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12082200

Chicago/Turabian StyleLatorre, Dani, Guillem Masó, Arlo Hinckley, David Verdiell-Cubedo, Gema Castillo-García, Anni G. González-Rojas, Erin N. Black-Barbour, Anna Vila-Gispert, Emili García-Berthou, Rafael Miranda, and et al. 2020. "Interpopulation Variability in Dietary Traits of Invasive Bleak Alburnus alburnus (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) Across the Iberian Peninsula" Water 12, no. 8: 2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12082200

APA StyleLatorre, D., Masó, G., Hinckley, A., Verdiell-Cubedo, D., Castillo-García, G., González-Rojas, A. G., Black-Barbour, E. N., Vila-Gispert, A., García-Berthou, E., Miranda, R., Oliva-Paterna, F. J., Ruiz-Navarro, A., da Silva, E., Fernández-Delgado, C., Cucherousset, J., Serrano, J. M., & Almeida, D. (2020). Interpopulation Variability in Dietary Traits of Invasive Bleak Alburnus alburnus (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) Across the Iberian Peninsula. Water, 12(8), 2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12082200