Towards the Implementation of Circular Economy in the Wastewater Sector: Challenges and Opportunities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

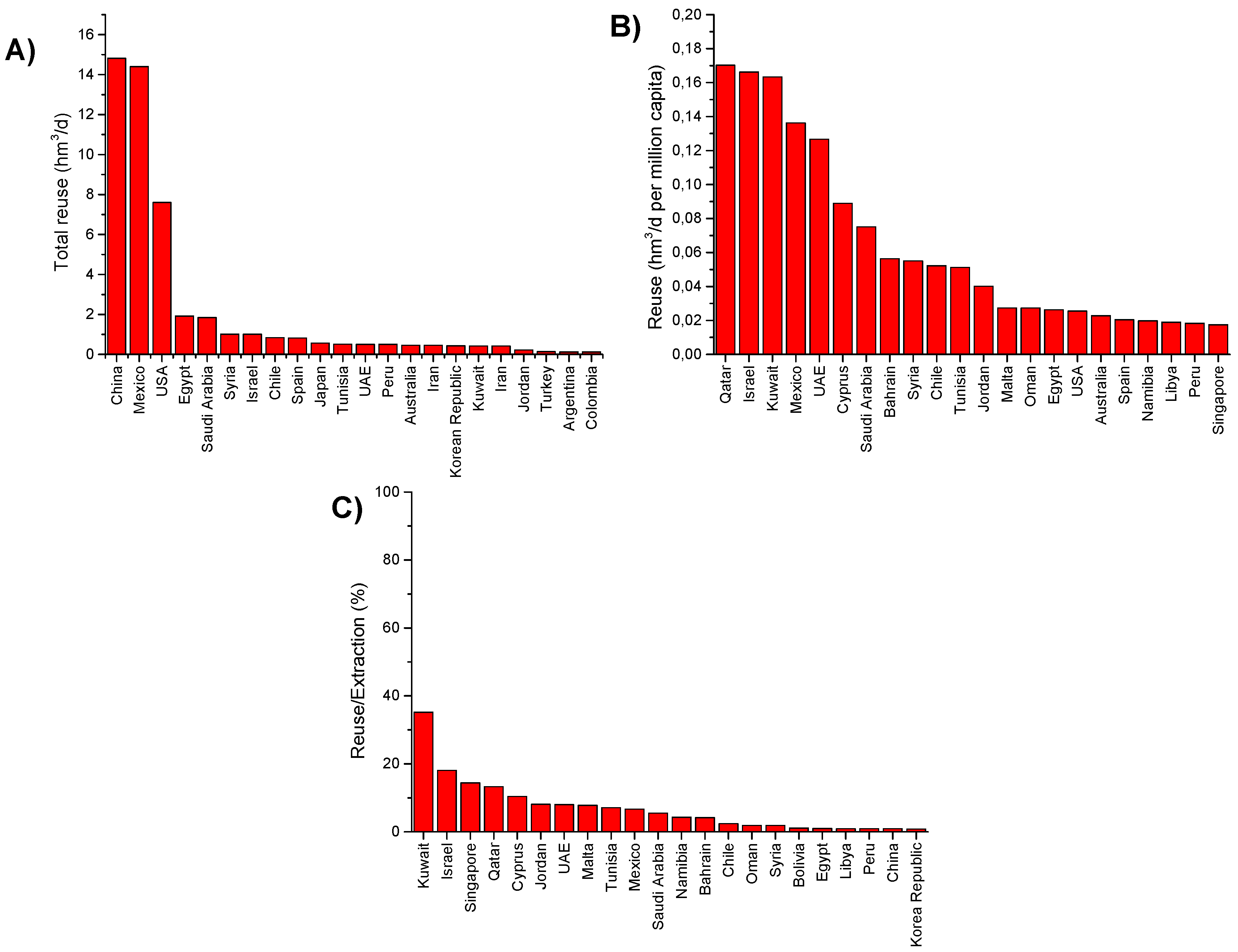

2. Wastewater Reclamation and Reuse

2.1. Definition and Overview of Reclamation around the World

2.2. Legislation and Guidelines Around the World

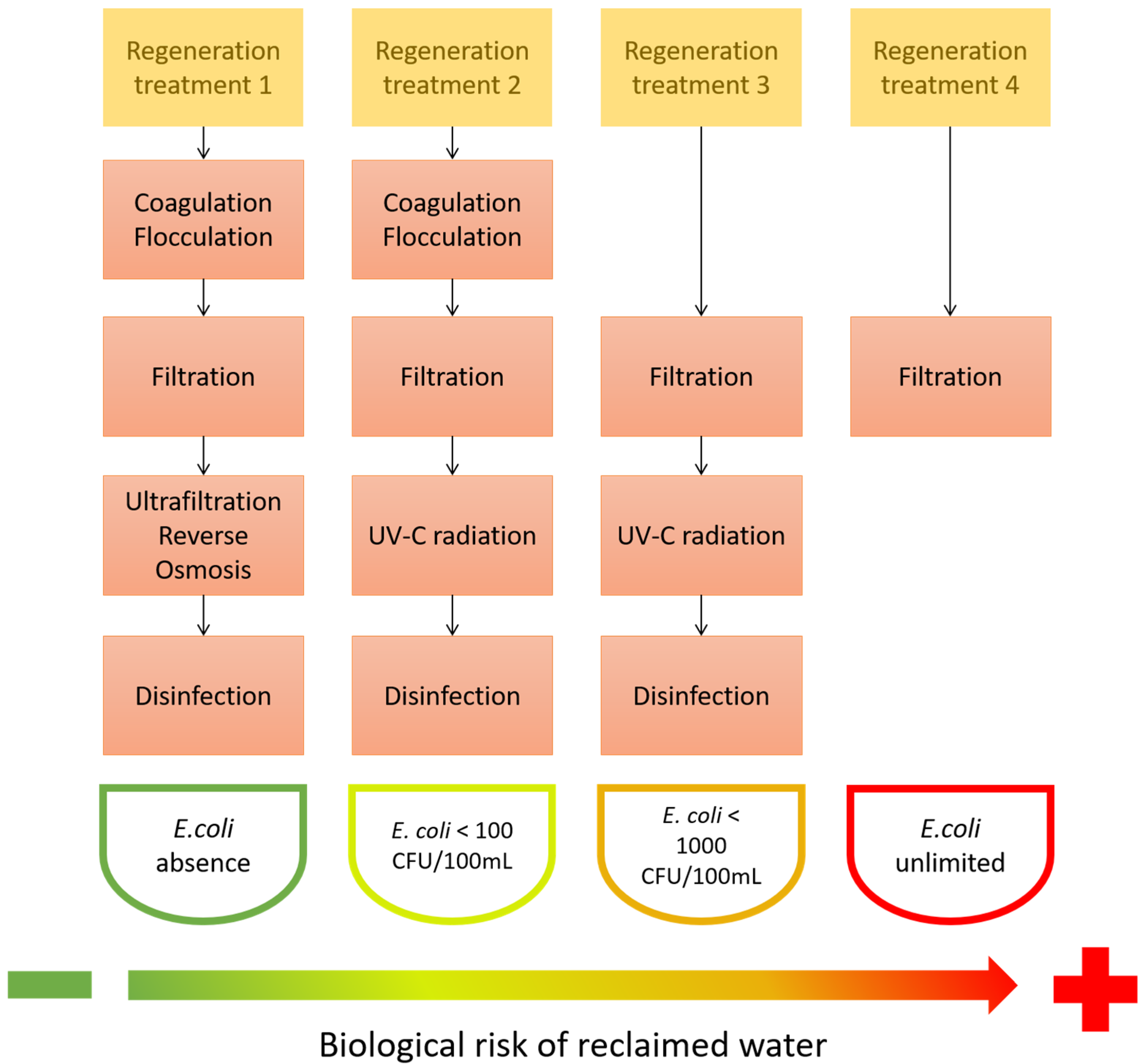

2.3. Risks of Reclaimed Wastewater

2.4. Tertiary Treatment in WWTP: Technologies for Wastewater Reclamation

3. Resources Recovery

3.1. Nutrients

3.2. High Added-Value Products

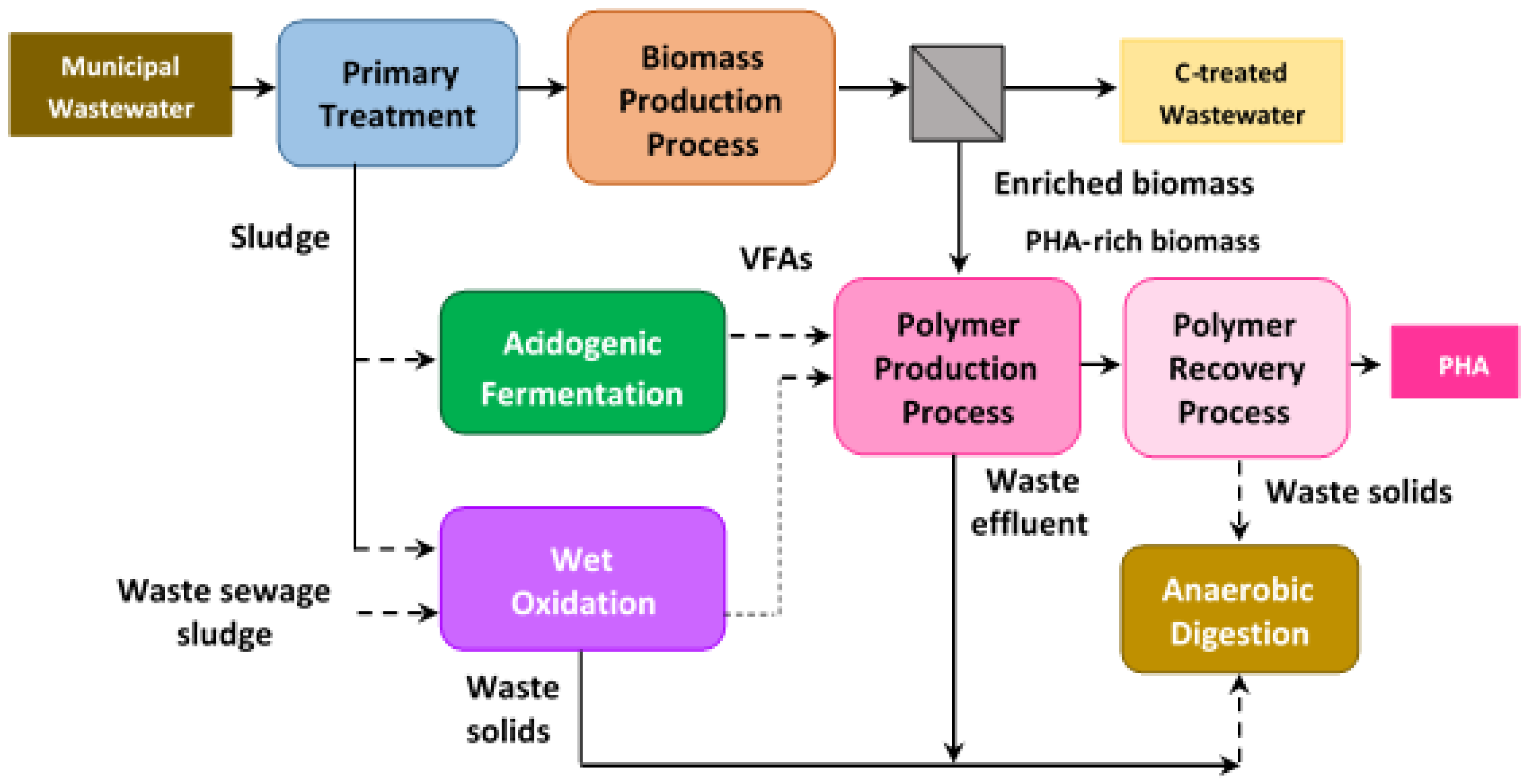

4. Sewage Sludge Valorisation

4.1. Nutrients

4.2. Heavy Metals

4.3. Adsorbents

4.4. Bioplastics

4.5. Construction Materials

4.6. Proteins

4.7. Hydrolytic Enzymes

5. Towards Energy Self-Sufficiency

5.1. Biogas Recovery

5.2. Biodiesel Production

5.3. Hydrogen and Syngas Production

5.4. Microbial Fuel Cell

5.5. Heat Pumps: Thermal Energy Recovery

5.6. Hydropower

5.7. Real Examples of Self-Sufficient WWTP

6. Outlook and Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ONU. Resolución aprobada por la Asamblea General el 28 de julio de 2010. 64/292. El Derecho Hum. Agua Saneam. 2010, 660, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hailu, D.; Rendtorff-Smith, S.; Gankhuyag, U.; Ochieng, C. Toolkit and Guidance for Preventing and Managing Land and Natural Resources Conflict; The United Nations Interagency Framework Team for Preventive Action: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDG. Sustainable Development Goal 6 Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gassert, F.; Reig, P.; Luo, T.; Maddocks, A. Aqueduct Country and River Basin Rankings: A Weighted Aggregation of Spatially Distinct Hydrological Indicators; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, December 2013; Available online: wri.org/publication/aqueduct-country-river-basin-rankings (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- COM. Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy; COM: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgot, M.; Folch, M. Tratamento de águas residuais e reutilização de agua. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 2, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricart, S.; Rico, A.M. Assessing technical and social driving factors of water reuse in agriculture: A review on risks, regulation and the yuck factor. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 217, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.D.; Asano, T. Recovering sustainable water from wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 201A–208A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyu, S.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W.; Fan, Y.; Jiao, W. Wastewater reclamation and reuse in China: Opportunities and challenges. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 39, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, B.; Büyükgüngör, H. Wastewater reclamation and reuse trends in Turkey: Opportunities and challenges. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 30, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, A.; Zoboli, O.; Krampe, J.; Rechberger, H.; Zessner, M.; Egle, L. Environmental impacts of phosphorus recovery from municipal wastewater. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 130, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzas, A.; Martí, N.; Grau, S.; Barat, R.; Mangin, D.; Pastor, L. Implementation of a global P-recovery system in urban wastewater treatment plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malila, R.; Lehtoranta, S.; Viskari, E.L. The role of source separation in nutrient recovery—Comparison of alternative wastewater treatment systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Q.; Aleem, M.; Fang, F.; Xue, Z.; Cao, J. Potentials and challenges of phosphorus recovery as vivianite from wastewater: A review. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikas, P. Towards energy positive wastewater treatment plants. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasham, O.; Dupont, V.; Camargo-Valero, M.A.; García-Gutiérrez, P.; Cockerill, T. Combined ammonia recovery and solid oxide fuel cell use at wastewater treatment plants for energy and greenhouse gas emission improvements. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, F.; Zeng, Q.; Hao, T.; Ekama, G.A.; Hao, X.; Chen, G. Achieving methane production enhancement from waste activated sludge with sulfite pretreatment: Feasibility, kinetics and mechanism study. Water Res. 2019, 158, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, K.; Song, H. Increased power generation from cylindrical microbial fuel cell inoculated with P. aeruginosa. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 141, 111394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemalatha, M.; Sravan, J.S.; Min, B.; Venkata Mohan, S. Microalgae-biorefinery with cascading resource recovery design associated to dairy wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 284, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, A.; Basu, S.; Raturi, S.; Batra, V.S.; Balakrishnan, M. Recovery of antioxidants from sugarcane molasses distillery wastewater and its effect on biomethanation. J. Water Process Eng. 2018, 25, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando-Pulido, J.M.; Corpas-Martínez, J.R.; Martinez-Ferez, A. About two-phase olive oil washing wastewater simultaneous phenols recovery and treatment by nanofiltration. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 114, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.A.; Carissimi, E.; Monje-Ramírez, I.; Velasquez-Orta, S.B.; Rodrigues, R.T.; Ledesma, M.T.O. Comparison between coagulation-flocculation and ozone-flotation for Scenedesmus microalgal biomolecule recovery and nutrient removal from wastewater in a high-rate algal pond. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 259, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peiter, F.S.; Hankins, N.P.; Pires, E.C. Evaluation of concentration technologies in the design of biorefineries for the recovery of resources from vinasse. Water Res. 2019, 157, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Baek, K. Selective recovery of ferrous oxalate and removal of arsenic and other metals from soil-washing wastewater using a reduction reaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Luo, X.; Deng, F.; Shao, P.; Wu, X.; Dionysiou, D.D. Combination of multi-oxidation process and electrolysis for pretreatment of PCB industry wastewater and recovery of highly-purified copper. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 354, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, N.; Mishra, S. A review on the recovery and separation of rare earths and transition metals from secondary resources. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, H.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Shi, J. Recovery of gold from electronic wastewater by Phomopsis sp. XP-8 and its potential application in the degradation of toxic dyes. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 288, 121610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Mei, X.; Ma, T.; Xue, C.; Wu, M.; Ji, M.; Li, Y. Green recovery of hazardous acetonitrile from high-salt chemical wastewater by pervaporation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Ling, B.; Li, Z.; Luo, S.; Sui, X.; Guan, Q. Fluorine removal and calcium fluoride recovery from rare-earth smelting wastewater using fluidized bed crystallization process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.; Sikarwar, V.S.; He, J.; Dastyar, W.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Wang, W.; Zhao, M. Opportunities and challenges in sustainable treatment and resource reuse of sewage sludge: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 337, 616–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laura, F.; Tamara, A.; Müller, A.; Hiroshan, H.; Christina, D.; Serena, C. Selecting sustainable sewage sludge reuse options through a systematic assessment framework: Methodology and case study in Latin America. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, E.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Zouari, N.; McKay, G. Removal of boron from water using adsorbents derived from waste tire rubber. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Sun, Q.; Wang, W.; Lu, L.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Utilizations of agricultural waste as adsorbent for the removal of contaminants: A review. Chemosphere 2018, 211, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, G.; Xie, S.; Pan, L.; Li, C.; You, F.; Wang, Y. Immobilization of heavy metals in ceramsite produced from sewage sludge biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z. A review on agro-industrial waste (AIW) derived adsorbents for water and wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 227, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-D.; Bai, S.; Li, R.; Su, G.; Duan, X.; Wang, S.; Ren, N.-Q.; Ho, S.-H. Magnetic biochar catalysts from anaerobic digested sludge: Production, application and environment impact. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, T.; Shen, M.; Huang, Z.; Chong, Y.; Cui, L. Coagulation treatment of swine wastewater by the method of in-situ forming layered double hydroxides and sludge recycling for preparation of biochar composite catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 369, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Yang, J.; Hou, H.; Liang, S.; Xiao, K.; Qiu, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, B.; Yu, W.; Deng, H. Enhanced sludge dewatering via homogeneous and heterogeneous Fenton reactions initiated by Fe-rich biochar derived from sludge. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 372, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cui, F. Iron sludge-derived magnetic Fe 0 /Fe 3 C catalyst for oxidation of ciprofloxacin via peroxymonosulfate activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 365, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Yuan, Y.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Guo, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, K.; Zhao, X.S. Waste-cellulose-derived porous carbon adsorbents for methyl orange removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 371, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Gu, L.; Yu, H.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, D.; Ye, J. Radical assisted iron impregnation on preparing sewage sludge derived Fe/carbon as highly stable catalyst for heterogeneous Fenton reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 352, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazner, C. Water Reclamation Technologies for Safe Managed Aquifer Recharge. Water Intell. Online 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confederación Hidrográfica del Segura. Available online: https://www.chsegura.es/chs/cuenca/resumendedatosbasicos/recursoshidricos/reutilizacion.html (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- World Water Assessment Programme (WWAP). The UN World Water Development Report 2017; Wastewater; The Untapped Resource: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, B.; Asano, T. Water reclamation and reuse around the world. In Water Reuse—An International Survey of Current Practice, Issues and Needs; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodar-Abellan, A.; López-Ortiz, M.I.; Melgarejo-Moreno, J. Wastewater Treatment and Water Reuse in Spain. Current Situation and Perspectives. Water 2019, 11, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ormad, M.P. Reutilización de Aguas Residuales Urbanas. Cátedra Mariano López Navarro; Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, O. Beyond NEWater: An insight into Singapore’s water reuse prospects. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 2, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woltersdorf, L.; Scheidegger, R.; Liehr, S.; Döll, P. Municipal water reuse for urban agriculture in Namibia: Modeling nutrient and salt flows as impacted by sanitation user behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 169, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Técnica y Proyectos Sociedad Anónima (TYPSA). Updated Report on Wastewater Reuse in the European Union. April 2013. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/blueprint/pdf/Final%20Report_Water%20Reuse_April%202013.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Behera, S.K.; Kim, H.W.; Oh, J.E.; Park, H.S. Occurrence and removal of antibiotics, hormones and several other pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment plants of the largest industrial city of Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4351–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosma, C.I.; Lambropoulou, D.A.; Albanis, T.A. Investigation of PPCPs in wastewater treatment plants in Greece: Occurrence, removal and environmental risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 466, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, P.; Olson, N.D.; Paulson, J.N.; Pop, M.; Maddox, C.; Claye, E.; Goldstein, R.E.R.; Sharma, M.; Gibbs, S.; Mongodin, E.F.; et al. Conventional wastewater treatment and reuse site practices modify bacterial community structure but do not eliminate some opportunistic pathogens in reclaimed water. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čelić, M.; Gros, M.; Farré, M.; Barceló, D.; Petrović, M. Pharmaceuticals as chemical markers of wastewater contamination in the vulnerable area of the Ebro Delta (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, F.; Matamoros, V.; Bayona, J.; Elsinga, G.; Hornstra, L.M.; Piña, B. Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in soils and crops. A field study in legume plants (Vicia faba L.) grown under different watering regimes. Environ. Res. 2019, 170, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jasim, S.Y.; Saththasivam, J.; Loganathan, K.; Ogunbiyi, O.O.; Sarp, S. Reuse of Treated Sewage Effluent (TSE) in Qatar. J. Water Process Eng. 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Mosteo, R.; Gómez, J.; Rubio, E.; Goñi, P.; Ormad, M.P. How does urban wastewater treatment affect the microbial quality of treated wastewater? Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 130, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosteo, R.; Ormad, M.P.; Goñi, P.; Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; García, A.; Clavel, A. Identification of pathogen bacteria and protozoa in treated urban wastewaters discharged in the Ebro River (Spain): Water reuse possibilities. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 68, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajonina, C.; Buzie, C.; Ajonina, I.U.; Basner, A.; Reinhardt, H.; Gulyas, H.; Liebau, E.; Otterpohl, R. Occurrence of cryptosporidium in a wastewater treatment plant in north germany. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A Curr. Issues 2012, 75, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z.; Hu, S.; Wang, J.; Qian, Z.; Feng, J.; Xian, Q.; Gong, T. Occurrence and ecological risk assessment of disinfection byproducts from chlorination of wastewater effluents in East China. Water Res. 2019, 157, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Ormad, M.P.; Mosteo, R.; Sarasa, J.; Ovelleiro, J.L. Conventional and Advanced Oxidation Processes Used in Disinfection of Treated Urban Wastewater. Water Environ. Res. 2015, 87, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguas, Y.; Hincapie, M.; Martínez-Piernas, A.B.; Agüera, A.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Nahim-Granados, S.; Polo-López, M.I. Reclamation of Real Urban Wastewater Using Solar Advanced Oxidation Processes: An Assessment of Microbial Pathogens and 74 Organic Microcontaminants Uptake in Lettuce and Radish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 9705–9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahim-Granados, S.; Pérez, J.S.; Polo-Lopez, M.I. Effective solar processes in fresh-cut wastewater disinfection: Inactivation of pathogenic E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enteritidis. Catal. Today 2018, 313, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahim-Granados, S.; Oller, I.; Malato, S.; Pérez, J.S.; Polo-Lopez, M.I. Commercial fertilizer as effective iron chelate (Fe3+-EDDHA) for wastewater disinfection under natural sunlight for reusing in irrigation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2019, 253, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Ormad, M.P.; Mosteo, R.; Canalis, S.; Ovelleiro, J.L. Escherichia coli Inactivation in Fresh Water Through Photocatalysis with TiO2-Effect of H2O2 on Disinfection Kinetics. Clean Soil Air Water 2016, 44, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, P.; Verbel, M.; Silva-Agredo, J.; Mosteo, R.; Ormad, M.P.; Torres-Palma, R.A. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes for Staphylococcus aureus disinfection in municipal WWTP effluents. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 198, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; García-Cañibano, C.; Lepistö, R.J.; Encinas, Á.; Pellinen, J.; Marugán, J. Intensification of UV-C tertiary treatment: Disinfection and removal of micropollutants by sulfate radical based Advanced Oxidation Processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 372, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Guerra-Rodríguez, S.; Raez, J.M.; López-Muñoz, M.J.M.-J.; Rodríguez, E. Assessment of different iron species as activators of S2O82− and HSO5− for inactivation of wild bacteria strains. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 248, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.C.; Castro-Alférez, M.; Nahim-Granados, S.; Polo-López, M.I.; Lucas, M.S.; Li Puma, G.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P. Inactivation of water pathogens with solar photo-activated persulfate oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 12, 9542–9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Robles, L.; Oller, I.; Polo-López, M.I.; Rivas-Ibáñez, G.; Malato, S. Microbiological evaluation of combined advanced chemical-biological oxidation technologies for the treatment of cork boiling wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 687, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Mesones, S.; Marugán, J. Hybrid UV-C/microfiltration process in membrane photoreactor for wastewater disinfection. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 26, 36080–36087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symonds, E.M.; Verbyla, M.E.; Lukasik, J.O.; Kafle, R.C.; Breitbart, M.; Mihelcic, J.R. A case study of enteric virus removal and insights into the associated risk of water reuse for two wastewater treatment pond systems in Bolivia. Water Res. 2014, 65, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sanctis, M.; Del Moro, G.; Chimienti, S.; Ritelli, P.; Levantesi, C.; Di Iaconi, C. Removal of pollutants and pathogens by a simplified treatment scheme for municipal wastewater reuse in agriculture. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 580, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shingare, R.P.; Nanekar, S.V.; Thawale, P.R.; Karthik, R.; Juwarkar, A.A. Comparative study on removal of enteric pathogens from domestic wastewater using Typha latifolia and Cyperus rotundus along with different substrates. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2017, 19, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voumard, M.; Giannakis, S.; Carratalà, A.; Pulgarin, C. E. coli—MS2 bacteriophage interactions during solar disinfection of wastewater and the subsequent post-irradiation period. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 359, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmanović, M.; Ginebreda, A.; Petrović, M.; Barceló, D. Risk assessment based prioritization of 200 organic micropollutants in 4 Iberian rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 503, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, D.; Petrovic, M. Challenges and achievements of LC-MS in environmental analysis: 25 years on. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2007, 26, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkutyte, J.; Varma, R.S.; Jegatheesan, V. Treatment of Micropollutants in Water and Wastewater; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Besha, A.T.; Gebreyohannes, A.Y.; Tufa, R.A.; Bekele, D.N.; Curcio, E.; Giorno, L. Removal of emerging micropollutants by activated sludge process and membrane bioreactors and the effects of micropollutants on membrane fouling: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2395–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, M.; Blum, K.M.; Jernstedt, H.; Renman, G.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Haglund, P.; Anderssion, P.L.; Wiberg, K.; Ahrens, L. Screening and prioritization of micropollutants in wastewaters from on-site sewage treatment facilities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 328, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, M.; Borova, V.; Boix, C.; Aalizadeh, R.; Bade, R.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Hernández, F. UHPLC-QTOF MS screening of pharmaceuticals and their metabolites in treated wastewater samples from Athens. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 323, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhaus, T.; Karlsson, M. Screening level mixture risk assessment ofpharmaceuticals in STP effluents. Water Res. 2014, 49, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esplugas, S.; Bila, D.M.; Krause, L.G.T.; Dezotti, M. Ozonation and advanced oxidation technologies to remove endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in water effluents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 149, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Pharmaceuticals in Drinking Water; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, J.; Almeida, V.; Rodrigues, C.; Ferreira, A.; Benoliel, E.; Cardoso, M.J.; Vale, V. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals in a water supply system and related human health risk assessment. Water Res. 2015, 72, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, B.W.; Hayes, E.P.; Fiori, J.M.; Mastrocco, F.J.; Roden, N.M.; Cragin, D.; Meyerhoff, R.D.; D’Aco, V.J.; Anderson, P.D. Human pharmaceuticals in US surface waters: A human health risk assessment. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2005, 42, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Garcia-Cañibano, C.; Sarro, M.; Encinas, A.; Medana, C.; Fabbri, D.; Calza, P.; Marugán, J. Evaluation of transformation products from chemical oxidation of micropollutants in wastewater by photoassisted generation of sulfate radicals. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Laski, E.; García-Cañibano, C.; Martín de Vidales, M.J.; Encinas, Á.; Kuch, B.; Marugán, J. Micropollutants removal by full-scale UV-C/sulfate radical based Advanced Oxidation Processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Mediano, A.; Pueyo, N.; García-Suescun, I.; Mosteo, R.; Ormad, M.P. Degradation of chloroform by Fenton-like treatment induced by electromagnetic fields: A case of study. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2016, 159, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaén-Gil, A.; Buttiglieri, G.; Benito, A.; Gonzalez-Olmos, R.; Barceló, D.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S. Metoprolol and metoprolol acid degradation in UV/H2O2 treated wastewaters: An integrated screening approach for the identification of hazardous transformation products. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 380, 120851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- te Brinke, E.; Reurink, D.M.; Achterhuis, I.; de Grooth, J.; de Vos, W.M. Asymmetric polyelectrolyte multilayer membranes with ultrathin separation layers for highly efficient micropollutant removal. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 18, 100471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenyvesi, É.; Barkács, K.; Gruiz, K.; Varga, E.; Kenyeres, I.; Záray, G.; Szente, L. Removal of hazardous micropollutants from treated wastewater using cyclodextrin bead polymer—A pilot demonstration case. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 383, 121181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruppelt, J.P.; Pinnekamp, J.; Tondera, K. Elimination of micropollutants in four test-scale constructed wetlands treating combined sewer overflow: Influence of filtration layer height and feeding regime. Water Res. 2020, 169, 115214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, M.B.; Fida, Z.; Tufail, A.; van de Merwe, J.P.; Leusch, F.D.L.; Pramanik, B.K.; Price, W.E.; Hai, F.I. Persulfate oxidation-assisted membrane distillation process for micropollutant degradation and membrane fouling control. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 222, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvestiti, J.A.; Cruz-Alcalde, A.; López-Vinent, N.; Dantas, R.F.; Sans, C. Catalytic ozonation by metal ions for municipal wastewater disinfection and simulataneous micropollutants removal. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 259, 118104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Ahmad, R.; Guo, J.; Tibi, F.; Kim, M.; Kim, J. Removals of micropollutants in staged anaerobic fluidized bed membrane bioreactor for low-strength wastewater treatment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 127, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrabi, M.; Varela Della Giustina, S.; Aloulou, F.; Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Barceló, D.; Elleuch, B. Analysis of multiclass antibiotic residues in urban wastewater in Tunisia. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2018, 10, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, D.; Castellet-Rovira, F.; Villagrasa, M.; Badia-Fabregat, M.; Barceló, D.; Vicent, T.; Caminal, G.; Sarrà, M.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S. The role of sorption processes in the removal of pharmaceuticals by fungal treatment of wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferre-Aracil, J.; Valcárcel, Y.; Negreira, N.; de Alda, M.L.; Barceló, D.; Cardona, S.C.; Navarro-Laboulais, J. Ozonation of hospital raw wastewaters for cytostatic compounds removal. Kinetic modelling and economic assessment of the process. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 556, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonnorat, J.; Kanyatrakul, A.; Prakhongsak, A.; Honda, R.; Panichnumsin, P.; Boonapatcharoen, N. Effect of hydraulic retention time on micropollutant biodegradation in activated sludge system augmented with acclimatized sludge treating low-micropollutants wastewater. Chemosphere 2019, 230, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kora, E.; Theodorelou, D.; Gatidou, G.; Fountoulakis, M.S.; Stasinakis, A.S. Removal of polar micropollutants from domestic wastewater using a methanogenic – aerobic moving bed biofilm reactor system. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 122983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatankhah, H.; Riley, S.M.; Murray, C.; Quiñones, O.; Steirer, K.X.; Dickenson, E.R.V.; Bellona, C. Simultaneous ozone and granular activated carbon for advanced treatment of micropollutants in municipal wastewater effluent. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillossou, R.; Le Roux, J.; Mailler, R.; Vulliet, E.; Morlay, C.; Nauleau, F.; Gasperi, J.; Rocher, V. Organic micropollutants in a large wastewater treatment plant: What are the benefits of an advanced treatment by activated carbon adsorption in comparison to conventional treatment? Chemosphere 2019, 218, 1050–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertagna Silva, D.; Cruz-Alcalde, A.; Sans, C.; Giménez, J.; Esplugas, S. Performance and kinetic modelling of photolytic and photocatalytic ozonation for enhanced micropollutants removal in municipal wastewaters. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 249, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Alcalde, A.; Esplugas, S.; Sans, C. Abatement of ozone-recalcitrant micropollutants during municipal wastewater ozonation: Kinetic modelling and surrogate-based control strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico de España (MITECO). Guía Para la Aplicación del R.D. 1620/2007 por el que se Establece el Régimen Jurídico de la Reutilización de las Aguas Depuradas (Ministerio). 2010. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/agua/publicaciones/GUIA%20RD%201620_2007__tcm30-213764.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- McConville, J.R.; Kvarnström, E.; Jönsson, H.; Kärrman, E.; Johansson, M. Source separation: Challenges & opportunities for transition in the swedish wastewater sector. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 120, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Otoo, M.; Drechsel, P.; Hanjra, M.A. Resource recovery and reuse as an incentive for a more viable sanitation service chain. Water Altern. 2017, 10, 493–512. [Google Scholar]

- Gottardo Morandi, C.; Wasielewski, S.; Mouarkech, K.; Minke, R.; Steinmetz, H. Impact of new sanitation technologies upon conventional wastewater infrastructures. Urban Water J. 2018, 15, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cieślik, B.; Konieczka, P. A review of phosphorus recovery methods at various steps of wastewater treatment and sewage sludge management. The concept of “no solid waste generation” and analytical methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1728–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrispim, M.; Scholz, M.; Nolasco, M.A. Phosphorus recovery from municipal wastewater treatment: Critical review of challenges and opportunities for developing countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchobanoglous, G.; Stensel, H.D.; Tsuchihashi, R.; Burton, F.; Abu-Orf, M.; Bowden, G.; Pfrang, W. Metcalf & Eddy/AECOM: Tratamento de Efluentes e Recuperação de Recursos, 5th ed.; AMGH Editora Ltda (Portugal): Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khiewwijit, R.; Temmink, H.; Rijnaarts, H.; Keesman, K.J. Energy and nutrient recovery for municipal wastewater treatment: How to design a feasible plant layout? Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 68, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egle, L.; Rechberger, H.; Krampe, J.; Zessner, M. Phosphorus recovery from municipal wastewater: An integrated comparative technological, environmental and economic assessment of P recovery technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mehta, C.M.; Khunjar, W.O.; Nguyen, V.; Tait, S.; Batstone, D.J. Technologies to Recover Nutrients from Waste Streams: A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 385–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johir, M.A.H.; George, J.; Vigneswaran, S.; Kandasamy, J.; Grasmick, A. Removal and recovery of nutrients by ion exchange from high rate membrane bio-reactor (MBR) effluent. Desalination 2011, 275, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocatürk-Schumacher, N.P.; Bruun, S.; Zwart, K.; Jensen, L.S. Nutrient Recovery From the Liquid Fraction of Digestate by Clinoptilolite. Clean Soil Air Water 2017, 45, 1500153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbe, C. Inventories Phosphorus Recycling Strategies and Technology (Web Document). P-Rex, 10.1.19. 2017. Available online: https://phosphorusplatform.eu/activities/p-recovery-technology-inventory (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Desmidt, E.; Ghyselbrecht, K.; Zhang, Y.; Pinoy, L.; Van der Bruggen, B.; Verstraete, W.; Rabaey, K.; Meesschaert, B. Global Phosphorus Scarcity and Full-Scale P-Recovery Techniques: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 336–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, C.; von Horn, J.; Tettenborn, F. Phosphorus Recovery from Wastewater-Expert Survey on Present Use and Future Potential. Water Environ. Res. A Res. Publ. Water Environ. Fed. 2012, 84, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, C.J.; Anastasiou, C.C.; O’Flaherty, V.; Mitchell, R. Bioremediation of olive mill wastewater. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2008, 61, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermeche, S.; Nadour, M.; Larroche, C.; Moulti-Mati, F.; Michaud, P. Olive mill wastes: Biochemical characterizations and valorization strategies. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 1532–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangui, A.; Abderrabba, M. Towards a high yield recovery of polyphenols from olive mill wastewater on activated carbon coated with milk proteins: Experimental design and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2018, 262, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiai, H.; Raiti, J.; El-Abbassi, A.; Hafidi, A. Recovery of phenolic compounds from table olive processing wastewaters using cloud point extraction method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogerakis, N.; Politi, M.; Foteinis, S.; Chatzisymeon, E.; Mantzavinos, D. Recovery of antioxidants from olive mill wastewaters: A viable solution that promotes their overall sustainable management. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gopinatha Kurup, G.; Adhikari, B.; Zisu, B. Recovery of proteins and lipids from dairy wastewater using food grade sodium lignosulphonate. Water Resour. Ind. 2019, 22, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, W.; Kennedy, A.; Wan, X.; Atiba, J.; McLaren, C.; Meyskens, F. Single dose administration of Bowman–Birk Inhibitor Concentrate (BBIC) in patients with oral leukoplakia. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. A Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 2000, 9, 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Long, J.; Hua, Y.; Chen, Y.; Kong, X.; Zhang, C. Protein recovery and anti-nutritional factor removal from soybean wastewater by complexing with a high concentration of polysaccharides in a novel quick-shearing system. J. Food Eng. 2019, 241, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Feng, D.; Qian, Y. Process Development, Simulation, and Industrial Implementation of a New Coal-Gasification Wastewater Treatment Installation for Phenol and Ammonia Removal. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 2874–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Tan, Y.; Yang, S.; Qian, Y. Development of phenols recovery process with novel solvent methyl propyl ketone for extracting dihydric phenols from coal gasification wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1632–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Xu, W.; Cao, H.; Ning, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sheng, Y. A novel phenol and ammonia recovery process for coal gasification wastewater altering the bacterial community and increasing pollutants removal in anaerobic/anoxic/aerobic system. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 661, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadipelly, C.; Pérez-González, A.; Yadav, G.D.; Ortiz, I.; Ibáñez, R.; Rathod, V.K.; Marathe, K.V. Pharmaceutical Industry Wastewater: Review of the Technologies for Water Treatment and Reuse. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 11571–11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; He, G.; Gao, P.; Chen, G. Development and characterization of composite nanofiltration membranes and their application in concentration of antibiotics. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2003, 30, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahtalebi, A.; Sarrafzadeh, M.; Rahmati, M. Application of nanofiltration membrane in the separation of amoxicillin from pharmaceutical waste water. Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2001, 8, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, P.; Neti, N.; Chavhan, C.; Pophali, G.; Kashyap, S.; Lokhande, S.; Gan, L. Treatment of refractory nano-filtration reject from a tannery using Pd-catalyzed wet air oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 261C, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission, E. Environmental, Economic and Social Impacts of the Use of Sewage Sludge on Land; Final Report; Part III: Project Interim Reports; Milieu Ltd.: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cieślik, B.M.; Namieśnik, J.; Konieczka, P. Review of sewage sludge management: Standards, regulations and analytical methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Lee, D.-J.; Chang, Y.; Lee, Y.-J. Sludge treatment: Current research trends. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, V.K.; Lo, S.L. Sludge: A waste or renewable source for energy and resources recovery? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 708–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Meenu, P.S.; Asha Latha, R.; Shashank, B.S.; Singh, D.N. Characterization of Sediments from the Sewage Disposal Lagoons for Sustainable Development. Advances in Civil Engineering Materials. ASTM Int. 2016, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, D.N. Characterization of Sediments for Sustainable Development: State of the Art. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2015, 33, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remy, C.; Boulestreau, M.; Warneke, J.; Jossa, P.; Kabbe, C.; Lesjean, B. Evaluating new processes and concepts for energy and resource recovery from municipal wastewater with life cycle assessment. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 73, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, S.; Grunert, M.; Müller, S. Overview of recent advances in phosphorus recovery for fertilizer production. Eng. Life Sci. 2018, 18, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaikake, K.; Sekito, T.; Dote, Y. Phosphate recovery from phosphorus-rich solution obtained from chicken manure incineration ash. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulchandani, A.; Westerhoff, P. Recovery opportunities for metals and energy from sewage sludges. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 215, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, J. Extraction of copper from sewage sludge using biodegradable chelant EDDS. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeken, A.H.M.; Hamelers, H.V.M. Removal of heavy metals from sewage sludge by extraction with organic acids. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesil, H.; Tugtas, A.E. Removal of heavy metals from leaching effluents of sewage sludge via supported liquid membranes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhai, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, T.; Chen, Y. Kinetic study of heavy metals Cu and Zn removal during sewage sludge ash calcination in air and N2 atmospheres. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 347, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; He, J.; Liu, T.; Xin, X.; Hu, H. Removal of heavy metal from sludge by the combined application of a biodegradable biosurfactant and complexing agent in enhanced electrokinetic treatment. Chemosphere 2017, 189, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshy, N.; Singh, D.N. Fly ash Zeolites for Water Treatment Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1460–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhang, N.; Xing, C.; Cui, Q.; Sun, Q. The adsorption, regeneration and engineering applications of biochar for removal organic pollutants: A review. Chemosphere 2019, 223, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.M.; Fowler, G.D.; Pullket, S.; Graham, N.J.D. Sewage sludge-based adsorbents: A review of their production, properties and use in water treatment applications. Water Res. 2009, 43, 2569–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Wei, X.-X.; Zeng, G.-M. Effect of pyrolysis temperature and hold time on the characteristic parameters of adsorbent derived from sewage sludge. J. Environ. Sci. 2004, 16, 683–686. [Google Scholar]

- Bagreev, A.; Bandosz, T.J.; Locke, D.C. Pore structure and surface chemistry of adsorbents obtained by pyrolysis of sewage sludge-derived fertilizer. Carbon 2001, 39, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inguanzo, M.; Menéndez, J.A.; Fuente, E.; Pis, J.J. Reactivity of pyrolyzed sewage sludge in air and CO2. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2001, 58–59, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, S.; Faur-Brasquet, C.; Le Coq, L.; Le Cloirec, P. Structure Characterization and Adsorption Properties of Pyrolyzed Sewage Sludge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 4249–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Tian, S.; Luo, R.; Liu, W.; Tu, Y.; Xiong, Y. Demineralization of sludge-based adsorbent by post-washing for development of porosity and removal of dyes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 88, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, S.; Le Coq, L.; Faur, C.; Le Cloirec, P. Production of porous carbonaceous adsorbent from physical activation of sewage sludge: Application to wastewater treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 2006, 53, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ros, A.; Lillo-Ródenas, M.A.; Fuente, E.; Montes-Morán, M.A.; Martín, M.J.; Linares-Solano, A. High surface area materials prepared from sewage sludge-based precursors. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Guo, Q.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Cheng, J. Adsorption of Methylene Blue in Acoustic and Magnetic Fields by Porous Carbon Derived from Sewage Sludge. Adsorpt. Sci. 2006, 24, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, A.; Lillo-Ródenas, M.A.; Canals-Batlle, C.; Fuente, E.; Montes-Morán, M.A.; Martin, M.J.; Linares-Solano, A. A New Generation of Sludge-Based Adsorbents for H2S Abatement at Room Temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 4375–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo-Ródenas, M.A.; Ros, A.; Fuente, E.; Montes-Morán, M.A.; Martin, M.J.; Linares-Solano, A. Further insights into the activation process of sewage sludge-based precursors by alkaline hydroxides. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 142, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.; Leung, Y.C.; Chua, H.; Wai-Hung, L.; Yu, P. Production of Polyhydroxybutyrate by Bacillus Species Isolated from Municipal Activated Sludge. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2001, 91–93, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takabatake, H.; Satoh, H.; Mino, T.; Matsuo, T. Recovery of biodegradable plastics from activated sludge process. Water Sci. Technol. 2000, 42, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, C.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Effect of temperature on storage polymers and settleability of activated sludge. Water Res. 1999, 33, 2374–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, R.D.; Surampalli, R.Y.; Yan, S.; Zhang, T.; Kao, C.M.; Lohani, B.N. Sustainable Sludge Management: Production of Value Added Products; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Sagastume, F.; Valentino, F.; Hjort, M.; Cirne, D.; Karabegovic, L.; Gerardin, F.; Johansson, P.; Karlsson, A.; Magnusson, P.; Alexandersson, T.; et al. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production from sludge and municipal wastewater treatment. Water Sci. Technol. A J. Int. Assoc. Water Pollut. Res. 2014, 69, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reddy, C.S.K.; Ghai, R.; Kalia, V.C. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 87, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Long, G.; Zhou, J.L.; Ma, C. Valorization of sewage sludge in the fabrication of construction and building materials: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 154, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xu, J.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Cao, B.; Huang, X.; Li, G. The utilization of lime-dried sludge as resource for producing cement. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 83, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-L.; Lin, D.F.; Luo, H.L. Influence of phosphate of the waste sludge on the hydration characteristics of eco-cement. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 168, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.H.; Show, K.Y. Properties of Cement Made from Sludge. J. Environ. Eng. 1991, 117, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, F.; Danesh, S.; Tavakkolizadeh, M.; Mohammadi-Khatami, M. Investigating chemical, physical and mechanical properties of eco-cement produced using dry sewage sludge and traditional raw materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, S.; Vàzquez, E. Stabilisation and solidification of sewage sludges with Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamood, A.; Khatib, J.M.; Williams, C. The effectiveness of using Raw Sewage Sludge (RSS) as a water replacement in cement mortar mixes containing Unprocessed Fly Ash (u-FA). Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 147, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchorab, Z.; Barnat-Hunek, D.; Franus, M.; Łagód, G. Mechanical and Physical Properties of Hydrophobized Lightweight Aggregate Concrete with Sewage Sludge. Materials 2016, 9, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tuan, B.L.A.; Hwang, C.-L.; Lin, K.-L.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Young, M.-P. Development of lightweight aggregate from sewage sludge and waste glass powder for concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Zhang, L.; Seo, S.; Lee, Y.-W.; Jahng, D. Protein recovery from excess sludge for its use as animal feed. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 8949–8954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- More, T.T.; Yadav, J.S.S.; Yan, S.; Tyagi, R.D.; Surampalli, R.Y. Extracellular polymeric substances of bacteria and their potential environmental applications. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, C.; Ji, X.; Zhong, Z.; Li, P. Recovery of protein from discharged wastewater during the production of chitin. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilli, S.; Bhunia, P.; Yan, S.; LeBlanc, R.J.; Tyagi, R.D.; Surampalli, R.Y. Ultrasonic pretreatment of sludge: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Weng, W.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. Comparison of protein extraction methods from excess activated sludge. Chemosphere 2020, 249, 126107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navia, R.; Soto, M.; Vidal, G.; Bornhardt, C.; Diez, C. Alkaline Pretreatment of Kraft Mill Sludge to Improve Its Anaerobic Digestion. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2003, 69, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz, M.; Sain, M. High-yield Protein Recovery from Secondary Sludge of Paper Mill Effluent and Its Characterization. Bioresources 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ras, M.; Girbal-Neuhauser, E.; Etienne, P.; Dominique, L. A high yield multi-method extraction protocol for protein quantification in activated sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 7464–7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Iglesias, O.; Urrea, J.L.; Oulego, P.; Collado, S.; Díaz, M. Valuable compounds from sewage sludge by thermal hydrolysis and wet oxidation. A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Lotti, T.; Lin, Y.; Malpei, F. Extracellular polymeric substances extraction and recovery from anammox granules: Evaluation of methods and protocol development. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 374, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chai, X.; Zhao, Y. Enhanced dewatering of waste-activated sludge by composite hydrolysis enzymes. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 39, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.H.; Rothman, H. Recycling sewage sludge as a food for farm animals: Some ecological and strategic implications for Great Britain. Agric. Wastes 1981, 3, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karn, S.; Kumar, A. Protease, lipase and amylase extraction and optimization from activated sludge of pulp and paper industry. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 57, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hoq, M.M.; Yamane, T.; Shimizu, S.; Funada, T.; Ishida, S. Continuous hydrolysis of olive oil by lipase in microporous hydrophobic membrane bioreactor. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1985, 62, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Gigras, P.; Mohapatra, H.; Goswami, V.K.; Chauhan, B. Microbial α-amylases: A biotechnological perspective. Process Biochem. 2003, 38, 1599–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabarlatz, D.; Vondrysova, J.; Jenicek, P.; Stüber, F.; Font, J.; Fortuny, A.; Fabregat, A.; Bengoa, C. Hydrolytic enzymes in activated sludge: Extraction of protease and lipase by stirring and ultrasonication. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010, 17, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolund, B.; Griebe, T.; Nielsen, P.H. Enzymatic activity in the activated-sludge floc matrix. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1995, 43, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Xing, X.; Matsumoto, K. Recoverability of protease released from disrupted excess sludge and its potential application to enhanced hydrolysis of proteins in wastewater. Biochem. Eng. J. 2002, 10, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessesse, A.; Dueholm, T.; Petersen, S.B.; Nielsen, P.H. Lipase and protease extraction from activated sludge. Water Res. 2003, 37, 3652–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karn, S.K.; Kumar, A. Sludge: Next paradigm for enzyme extraction and energy generation. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 49, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.J.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y. Energy self-sufficient biological municipal wastewater reclamation: Present status, challenges and solutions forward. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 269, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Liu, S.; Hu, H.Y.; Dong, X.; Wen, X. Water and energy recovery: The future of wastewater in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 637–638, 1466–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gude, V.G. Wastewater treatment in microbial fuel cells - An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, R.; Pérez-Elvira, S.I.; Fdz-Polanco, F. Energy feasibility study of sludge pretreatments: A review. Appl. Energy 2015, 149, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Elsayed, N.; Rezaei, N.; Guo, T.; Mohebbi, S.; Zhang, Q. Wastewater-based resource recovery technologies across scale: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olkiewicz, M.; Plechkova, N.V.; Earle, M.J.; Fabregat, A.; Stüber, F.; Fortuny, A.; Font, J.; Bengoa, C.; Capafons, J.F. Biodiesel production from sewage sludge lipids catalysed by Brønsted acidic ionic liquids. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 181, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, C.; Ma, L.; Chen, Y.; Tsubaki, N. Bio-syngas production from biomass catalytic gasification. Energy Convers. Manag. 2007, 48, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Du, P.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H.; Cheng, X.; Chang, B.; Wang, Z. Advances in microbial fuel cells for wastewater treatment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Lei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yao, Y. A review on the current research and application of wastewater source heat pumps in China. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2018, 6, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, C.; Samora, I.; Manso, P.; Rossi, L.; Heller, P.; Schleiss, A.J. Assessment of hydropower potential in wastewater systems and application to Switzerland. Renew. Energy 2017, 113, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Linville, J.L.; Urgun-Demirtas, M.; Mintz, M.M.; Snyder, S.W. An overview of biogas production and utilization at full-scale wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in the United States: Challenges and opportunities towards energy-neutral WWTPs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gherghel, A.; Teodosiu, C.; De Gisi, S. A review on wastewater sludge valorisation and its challenges in the context of circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalami, D.; Carrere, H.; Monlau, F.; Abdelouahdi, K.; Oukarroum, A.; Barakat, A. Pretreatment and co-digestion of wastewater sludge for biogas production: Recent research advances and trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 114, 109287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.H.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.S.; Liu, Y.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Nghiem, L.; Ni, B.J. Challenges in the application of microbial fuel cells to wastewater treatment and energy production: A mini review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, A.; Siles, J.A.; Martín, M.A.; Chica, A.F.; Estévez-Pastor, F.S.; Toro-Baptista, E. Effect of microwave pretreatment on semi-continuous anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge. Renew. Energy 2018, 115, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoite, G.M.; Vaidya, P.D. Iron-catalyzed wet air oxidation of biomethanated distillery wastewater for enhanced biogas recovery. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 226, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.H.; Chang, S.; Liu, Y. Biological hydrolysis pretreatment on secondary sludge: Enhancement of anaerobic digestion and mechanism study. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, M.; Lagerkvist, A.; Morgan-Sagastume, F. Energy balance performance of municipal wastewater treatment systems considering sludge anaerobic biodegradability and biogas utilisation routes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4680–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ji, M.; Wang, F.; Li, R.; Zhang, K.; Yin, X.; Li, Q. Damage of EPS and cell structures and improvement of high-solid anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge by combined (Ca(OH)2 + multiple-transducer ultrasonic) pretreatment. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 22706–22714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruffino, B.; Campo, G.; Genon, G.; Lorenzi, E.; Novarino, D.; Scibilia, G.; Zanetti, M. Improvement of anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge in a wastewater treatment plant by means of mechanical and thermal pre-treatments: Performance, energy and economical assessment. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 175, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ni, B.-J.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, G.; Li, X.; et al. Improved methane production from waste activated sludge by combining free ammonia with heat pretreatment: Performance, mechanisms and applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 268, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maria, F.; Micale, C.; Contini, S. Energetic and environmental sustainability of the co-digestion of sludge with bio-waste in a life cycle perspective. Appl. Energy 2016, 171, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-M.; Oh, J.-I.; Kim, J.-G.; Kwon, H.-H.; Park, Y.-K.; Kwon, E.E. Valorization of sewage sludge via non-catalytic transesterification. Environ. Int. 2019, 131, 105035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, O.K.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, J.W. Bench-scale production of sewage sludge derived-biodiesel (SSD-BD)and upgrade of its quality. Renew. Energy 2019, 141, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, F.; Qi, J.; Zhao, L. Biodiesel Production from Sewage Sludge by Using Alkali Catalyst Catalyze. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 31, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, F.; Dong, Y.; Wu, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, T.; Han, M. Function promotion of SO42−/Al2O3–SnO2 catalyst for biodiesel production from sewage sludge. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.B.A.; Akilli, H. Supercritical water gasification of wastewater sludge for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 10328–10349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Xiang, W. Steam gasification of sewage sludge with CaO as CO2 sorbent for hydrogen-rich syngas production. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 107, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Y. High quality syngas produced from the co-pyrolysis of wet sewage sludge with sawdust. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 5463–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarımtepe, C.C.; Türen, B.; Oz, N.A. Hydrogen production from municipal wastewaters via electrohydrolysis process. Chemosphere 2019, 231, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, T.M.; Banu, J.R.; Gunasekaran, M.; Kumar, G. Biohydrogen production from industrial wastewater: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fang, M.; Fang, Z.; Bu, H. Effects of sludge pretreatments and organic acids on hydrogen production by anaerobic fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8731–8735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbeshbishy, E.; Hafez, H.; Nakhla, G. Enhancement of biohydrogen producing using ultrasonication. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 6184–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tian, S.; Kan, T.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, H.; Strezov, V.; Jiang, Y. Sorption-enhanced thermochemical conversion of sewage sludge to syngas with intensified carbon utilization. Appl. Energy 2019, 254, 113663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Lu, G.; Wang, J.; Hu, H.; Yao, H. Effect of Fe/Ca-based composite conditioners on syngas production during different sludge gasification stages: Devolatilization, volatiles homogeneous reforming and heterogeneous catalyzing. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 29150–29158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantoko, D.; Kanchanatip, E.; Yan, M.; Weng, Z.; Gao, Z.; Zhong, Y. Assessment of sewage sludge gasification in supercritical water for H2-rich syngas production. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 131, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Liu, J.; Hantoko, D.; Kanchanatip, E.; Grisdanurak, N.; Cai, Y.; Gao, Z. Hydrogen-rich syngas production by catalytic cracking of tar in wastewater under supercritical condition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 19908–19919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, C.; Shi, X.; Sun, J.; Cunningham, J.A. Municipal wastewater treatment plants coupled with electrochemical, biological and bio-electrochemical technologies: Opportunities and challenge toward energy self-sufficiency. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, L. Simultaneous sulfide removal, nitrogen removal and electricity generation in a coupled microbial fuel cell system. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 291, 121888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goenka, R.; Mukherji, S.; Ghosh, P.C. Characterization of electrochemical behaviour of Escherichia coli MTCC 1610 in a microbial fuel cell. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2018, 3, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, E.; Erben, J.; Zengerle, R.; Gescher, J.; Kerzenmacher, S. Systematic investigation of anode materials for microbial fuel cells with the model organism G. sulfurreducens. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2018, 2, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikhil, G.N.; Krishna Chaitanya, D.N.S.; Srikanth, S.; Swamy, Y.V.; Venkata Mohan, S. Applied resistance for power generation and energy distribution in microbial fuel cells with rationale for maximum power point. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 335, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, S. Critical parameters selection in polarization behavior analysis of microbial fuel cells. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2018, 3, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, R.; Kannah, R.Y.; Sindhu, J.; Ragavi Kumar, G.; Gunasekaran, M.; Banu, J.R. Trends and resource recovery in biological wastewater treatment system. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Kumar, V.; Malyan, S.K.; Sharma, J.; Mathimani, T.; Maskarenj, M.S.; Ghosh, P.C.; Pugazhendhi, A. Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) for bioelectrochemical treatment of different wastewater streams. Fuel 2019, 254, 115526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kracke, F.; Vassilev, I.; Krömer, J.O. Microbial electron transport and energy conservation - The foundation for optimizing bioelectrochemical systems. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mei, X.; Xing, D.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Guo, C.; Ren, N. Adaptation of microbial community of the anode biofilm in microbial fuel cells to temperature. Bioelectrochemistry 2017, 117, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, G.; Jung, H.Y.; Sadhasivam, T.; Kurkuri, M.D.; Kim, S.C.; Roh, S.H. A comprehensive review on microbial fuel cell technologies: Processes, utilization, and advanced developments in electrodes and membranes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 598–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, J.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Jiang, H.; Liu, R. Energy recovery from wastewater: Heat over organics. Water Res. 2019, 161, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepbasli, A.; Biyik, E.; Ekren, O.; Gunerhan, H.; Araz, M. A key review of wastewater source heat pump (WWSHP) systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 88, 700–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurđević, D.; Balić, D.; Franković, B. Wastewater heat utilization through heat pumps: The case study of City of Rijeka. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, K.J.; Ren, X. Flexible and stable heat energy recovery from municipal wastewater treatment plants using a fixed-inverter hybrid heat pump system. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Lei, Z.; Lv, G.; Ni, L.; Deng, S. An experimental investigation on a novel WWSHP system with the heat recovery through the evaporation of wastewater using circulating air as a medium. Energy Build. 2019, 191, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Y. An experimental and numerical study of a de-fouling evaporator used in a wastewater source heat pump. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 70, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, M.A.; Badruzzaman, M.; Cherchi, C.; Swindle, M.; Ajami, N.; Jacangelo, J.G. Recent innovations and trends in in-conduit hydropower technologies and their applications in water distribution systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 228, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ak, M.; Kentel, E.; Kucukali, S. A fuzzy logic tool to evaluate low-head hydropower technologies at the outlet of wastewater treatment plants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, K.J.; Kim, I.S.; Ren, X.; Cheon, K.H. Reliable energy recovery in an existing municipal wastewater treatment plant with a flow-variable micro-hydropower system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 101, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, C.; McNabola, A.; Coughlan, P. Development of an evaluation method for hydropower energy recovery in wastewater treatment plants: Case studies in Ireland and the UK. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2014, 7, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, P.; Wang, H.; Robinson, Z.P.; Li, F. The feasibility and challenges of energy self-sufficient wastewater treatment plants. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, O.; Keil, S.; Fimml, C. Examples of energy self-sufficient municipal nutrient removal plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 64, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzenbeck, N.; Pfeiffer, W.; Bomball, E. Can a wastewater treatment plant be a powerplant? A case study. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 57, 1555–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wett, B.; Buchauer, K.; Fimml, C. Energy self-sufficiency as a feasible concept for wastewater treatment systems. In Proceedings of the IWA Leading Edge Technology Conference, Asian Water, Singapore, 21–24 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, G.V. Best Practices for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment: Initial Case Study Incorporating European Experience and Evaluation Tool Concept; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2010; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ostapczuk, R.E.; Bassette, P.C.; Dassanayake, C.; Smith, J.E.; Bevington, G. Achieving zero net energy utilization at municipal WWTPs: The gloversville-johnstown joint WWTP experience. Proc. Water Environ. Fed. 2011, 2011, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J.; Stone, L.; Durden, K.; Beecher, N.; Hemenway, C.; Greenwood, R. Barriers to biogas use for renewable energy. Water Environ. Res. Found 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.Y. Mass Flow and Energy Efficiency of Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wiser, J.; Schettler, J.; Willis, J. Evaluation of Combined Heat and Power Technologies for Wastewater Facilities. 2010. Available online: http://www.cwwga.org/documentlibrary/121_EvaluationCHPTechnologiespreliminary%5B1%5D.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2020).

| Country | Agriculture | Municipal | Potable Unplanned Indirect Reuse | Groundwater Recharge | Industrial | Environment | Drinking Water | Regulations/Guidelines | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union countries | Austria | X | No | ||||||

| Belgium | X | X | X | X | Under preparation. | ||||

| Bulgaria | X | Under preparation. | |||||||

| Cyprus | X | X | X | X | X | D 296/03.06.2005 | |||

| Czech Republic | No | ||||||||

| Denmark | X | No | |||||||

| Estonia | X | No | |||||||

| Finland | X | No | |||||||

| France | X | X | X | X | X | D 94/463.3.1994 DGS/SD1.D91 Guidelines 1996 | |||

| Germany | X | X | X | X | X | X | Under preparation. | ||

| Greece | X | X | JMD 145116/11 GG B’ 192/1997 | ||||||

| Hungary | 96/2009 (XII.9) | ||||||||

| Italy | X | X | X | X | D152/2006 | ||||

| Ireland | No | ||||||||

| Latvia | No | ||||||||

| Lithuania | No | ||||||||

| Luxembourg | X | No | |||||||

| Malta | X | X | X | Under preparation. | |||||

| Netherlands | X | X | X | No | |||||

| Poland | Under preparation. | ||||||||

| Portugal | X | X | X | X | X | X | RecIRAR 2/2007 ERDAR Guidelines | ||

| Romania | No | ||||||||

| Slovakia | No | ||||||||

| Slovenia | No | ||||||||

| Spain | X | X | X | X | X | RD 1620/2007 Guidelines from Regional Health Authorities | |||

| Sweden | X | X | X | No | |||||

| Countries outside European Union | United Kingdom | X | X | X | X | X | Under preparation. | ||

| India | Not yet | ||||||||

| Mexico | X | X | X | CONAGUA (Water National Commission) NOM-003-SEMARNAT-1997; NOM-004-SEMARNAT-2002 | |||||

| Australia | X | X | X | X | X | Water Quality Australia. Different guidelines for water recycling. | |||

| Jordan | X | Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for water reuse in agriculture (2006) | |||||||

| Singapore | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Singapore’s national water agency. Reclaimed water obeys the World Health Organization’s drinking water guidelines | |

| South Africa | X | X | X | X | X | X | Not yet, just some text addressing reuse briefly: Water Services Act of 1997; National Water Act of 1998, 37(1); DNHPD. Guide: permissible utilization and disposal of treated sewage effluent. Report No. 11/2/5/3; 1978. | ||

| China | X | X | X | X | X | X | GB/T 18920-2002; GB/T 18921-2002; GB/T 19923-2005; GB/T 19772-2005; GB 20922-2007 | ||

| Namibia | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Water supply and sanitation policy, 2008 | |

| Pathogens | Technology Applied | Efficiency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli Enterococcus sp. | H2O2/UV-vis | 4–5 log | [61] |

| E. coli Salmonella spp. Enterococcus spp. | Photo-fenton H2O2/UV-vis | Above detection limit | [62] |

| E. coli O157:H7 Salmonella Enteritidis | H2O2/solar | >6 log | [63] |

| E. coli O157:H7 Salmonella Enteritidis | Fe3+-EDDHA/H2O2/UV-vis | 5 log | [64] |

| E. coli | TiO2/UV | 3.30 log | [65] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Photo-electro-Fenton | 5 log | [66] |

| Enterococcus sp. E. coli | PS/UV-A/Iron | 3.5 log 5 log | [67] |

| Enterococcus faecalis E. coli | PMS/UV-C/Fe(II) | 5.2 log 5.7 log | [68] |

| E. coli Enterococcus faecalis | PS/solar | 6 log | [69] |

| Total heterotrophic bacteria | Combined photo-Fenton and aerobic biological treatment | 2 log | [70] |

| E. coli Enterococcus sp. Candida Albicans | UV-C/microfiltration | 4.2 log 4.7 log 3.1 log | [71] |

| Enteric Virus | Wastewater treatment pond | 3 log | [72] |

| E. coli C. perfringens | Sequencing batch biofilter granular reactors | 4 log 1 log | [73] |

| Total coliform | Constructed wetlands | 5.1 log | [74] |

| E. coli MS2 bacteriophage | Solar Disinfection | 6 log 3 log | [75] |

| Micropollutant | Technology Applied | Removal Efficiency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCF, SMX, CBZ, ATN, TCS, SCL | PMS or PS/Fe(II)/UV-C | 100% | [68] |

| ATN, BPA, CBZ, CFN, DCF, IBP, SMX | PMS/Fe(II)/UV-C | 40–100% | [88] |

| 25 MPs | H2O2/UV-C PMS/UV-C | 55% 48% | [89] |

| Chloroform | Fenton/Radiofrequency | 69% DOC | [90] |

| Metoprolol Metoprolol acid | H2O2/UV | 71.6 ± 0.8% 88.7 ± 1.1% | [91] |

| 8 MPs | Nanofiltration | 98% | [92] |

| 7 MPs | Sorption | >80% | [93] |

| Metoprolol Benzotriazole, DCF, BPA CBZ, SMX | Constructed wetlands | 70% 30–40% 0% | [94] |

| 12 MPs | PS-assisted Membrane distillation | >99% | [95] |

| ACMP, ATZ, DDVP | Ozonation | 80–100% | [96] |

| DCF, IBP, SMX | Membrane bioreactor | 100% | [97] |

| 13 antibiotics | Bioreactors | 33–88% | [98] |

| CBZ, DCF, Iopromide, Venlafaxine | Fungal treatment | 55–96% | [99] |

| Cytostatic compounds | Ozonation | 100% | [100] |

| 7 MPs | Activated Sludge | 75–93% | [101] |

| Four benzotriazoles | Moving bed biofilm reactor | 31–97% | [102] |

| DEET, SCL, primidone, TCEP, meprobamate | O3/granulated AC | 45–90% | [103] |

| 48 MPs | Activated Carbon (AC) Adsorption | 20–99% | [104] |

| ACMP | Photocatalytic ozonation | 89–100% | [105] |

| ATZ, IBP | Ozonation | 100% | [106] |

| Process | Raw Material | Resource Recovered | Main Results | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ostara Pearl®: crystallization | Dewatering liquor, thickening supernatant, digester supernatant | Phosphorus | Recovery around 80%–90% as struvite. Concentration of phosphorus (PO4-P) in the influent from 100 to 900 mg/L. MgCl2 is added as a source of magnesium. | High degree of recovery. Very high efficiency as fertilizer for acidic soil and high for alkaline soil. | High consumption of MgCl2. High operating costs. Decrease in the acidification potential. | [11,113,115,119] |

| PhosNix®: crystallization | Sludge dewatering liquor, wastewater after digestion | Phosphorus | Recovery around 80%–90% as struvite. Concentration of phosphorus (PO4-P) in the influent from 100 to 150 mg/L. Mg(OH)2 is added as a source of magnesium. | High degree of recovery. | High consumption of Mg(OH)2. High operating costs. | [113,120] |

| AirPrex®: precipitation/ crystallization | Sludge liquor, digested sludge before dewatering | Phosphorus | Recovery around 80% as struvite. Concentration of phosphorus in the influent from 150 to 250 mg/L. MgCl2 is added as a source of magnesium. | High degree of recovery. Very high efficiency as fertilizer for acidic soil and high for alkaline soil. | High consumption of MgCl2. High operating costs. Decrease in the acidification potential. | [11,113,119,120] |

| PHOSPAQ®: precipitation | Digester supernatant, sludge dewatering liquor, | Phosphorus | Recovery from 70% to 95% as struvite. Concentration of phosphorus (PO4-P) in the influent between 50 to 65 mg/L. MgO is added as a source of magnesium. | High degree of recovery. | High consumption of MgO. High operating costs. | [113,119,120] |

| DHV Crystalactor: crystallization | Digester supernatant | Phosphorus | Recovery around 85%–95% as calcium or magnesium phosphate or struvite pellets. Concentration of phosphorus (PO4-P) in the influent higher than 25 mg/L. | High degree of recovery. High efficiency as fertilizer for acidic soil and moderate for alkaline soil. | High consumption of Mg source. High operating costs. Increase in the acidification potential. | [113,116,119] |

| P-Roc®: crystallization | Digester supernatant | Phosphorus | Recovery around 85%–95% as calcium phosphate or struvite. Concentration of phosphorus (P) in the influent 25 mg/L. | High degree of recovery. Very high efficiency as fertilizer for acidic soil and high for alkaline soil. | High operating costs. Decrease in the acidification potential. | [113,115,121] |

| PRISA: precipitation/ crystallization | Digester supernatant | Phosphorus | Recovery around 85%–95% as struvite. Concentration of phosphorus in the influent between 50 and 60 mg/L. | High degree of recovery. Very high efficiency as fertilizer for acidic soil and high for alkaline soil. | High consumption of MgO. High operating costs. Decrease in the acidification potential | [115] |

| Ion-exchange | WWTP effluent from MBR reactor | Phosphorus, nitrogen | Retention of PO43− of 85%, NO3− of 95% by two ion- exchange columns. Around 95–98% phosphate and nitrate recovery during regeneration of columns. | High degree of recovery. Simple operation. | Regeneration of the resins. High consumption of NaCl. | [117] |

| Adsorption with Clinoptilolite (zeolite) | Digestate supernatant | Phosphorus, ammonium, potassium | Removal efficiencies varied from 64% to 80% for orthophosphate, 40% to 89% for ammonium and 37% to 78% for potassium. | High to moderate degree of recovery. Simple operation. | Regeneration or substitution of the zeolite. | [118] |

| Process | Raw Material | Resource Recovered | Main Results | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Olive oil wastewater | Polyphenols | Extraction yield 80% and overall efficiencies for total phenols 75.4%. Recovery of hydroxytyrosol 90.6%. | High percentage of recovery. Use of biodegradable and natural coating agent. | Regeneration or substitution of the activated carbon. | [124] |

| Cloud Point Extraction | Olive oil wastewater | Polyphenols | Recoveries of 65%, 62% and 68% for Triton X-100, Tween 80 and Genapol X-080 with the optimum conditions. | Biodegradable nature of the extractants. | High consumption of chemicals. | [125] |

| Precipitation | Dairy wastewater | Proteins and lipids | Recovery of proteins and lipids: 46% (mainly caseins) and 96% with lignosulphonate (coagulant). | High percentage of protein recovery. Low temperature. | High consumption of chemicals. Acidic pH. | [127] |

| Complexation | Soybean wastewater | Proteins | Recovery of proteins 87.5% and 78.5% with ι-carrageenan and dextran sulphate. Recovery of proteins <50% with xanthan gum and sodium alginate. | High percentage of recovery. Use of biodegradable complexing agents | High consumption of chemicals. | [129] |

| Extraction | Coal gasification wastewater | Phenols | Recovery of total phenol 99.6% with methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK) after three-stage extraction. | High percentage of recovery. | High consumption of chemicals. Toxic nature of MIBK. | [131] |

| Nanofiltration | Pharmaceutical wastewater | Active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) | Recovery of amoxicillin 97% with a polypiperazine amide membrane (permeate flux of 1.5 L/min·m2). | High recovery. Simple operation. Low operating costs. | Short membrane lifetime. Membrane fouling and cleaning. | [135] |

| Process | Raw Material | Resource Recovered | Main Results | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gifhorn: wet chemical and precipitation | Thickened sludge, dewatered sludge, digested sludge | Phosphorus | Recovery around 35%–60% as calcium phosphate, iron phosphate or struvite. | Relatively high recovery. Reduction of the need of flocculating agents in WWTP. High decontamination potential for heavy metals. | High consumption of chemicals. Increase in the Acidification potential. | [11,115,119] |

| Stuttgart: wet chemical and precipitation | Digested sludge | Phosphorus | Recovery around 35%–60% as calcium phosphate, iron phosphate or struvite. | Relatively high recovery. Reduction of the need of flocculating agents in WWTP. High decontamination potential for heavy metals. | High consumption of chemicals. Increase in the Acidification potential. | [11,115,119] |

| Budenheim ExtraPhos: wet chemicaland precipitation | Digested sludge | Phosphorus | Recovery around 40%–60% as dicalcium phosphate. | Relatively high recovery. Reduction of the need of flocculating agents in WWTP. | High consumption of chemicals. High operating costs. | [144,115,119] |

| Aqua Reci: supercritical water oxidation, acidic/alkaline leaching and precipitation | Thickened sludge, dewatered sludge, digested sludge | Phosphorus | Recovery around 40%–60% as calcium phosphate, iron phosphide and aluminium phosphide. | Relatively high recovery. Reduction of the need of flocculating agents in WWTP. High decontamination potential for heavy metals. | High consumption of chemicals. High operating costs. Increase in the Acidification potential. | [11,115,121] |

| LOPROX PHOXNAM: wet oxidation and precipitation | Thickened sludge, dewatered sludge, digested sludge | Phosphorus | Recovery around 40%–50% as struvite. | Relatively high recovery. Reduction of the need of flocculating agents in WWTP. High decontamination potential for heavy metals. | High consumption of oxygen and chemicals. High operating costs. | [11,115,121] |

| MEPHREC: Metallurgic melt-gassing | Dewatered Sludge briquettes | Phosphorus | Recovery around 65%–70% as P-rich slag. | Relatively high recovery. Reduction of the need of flocculating agents in WWTP. No need of mono-incineration. No increase in acidification potential. | High consumption of coke, dolomite and oxygen. High operating costs. | [143,11,115] |

| Process | Raw Material | Resource Recovered | Main Results | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction with chelants: EDDS and EDTA | Sewage sludge from WWTP | Heavy metals | Heavy metals in sewage sludge = 10:1. Higher extraction of Cu than other metals with EDDS. Cu recovery of 70% with EDDS at pH > 4.5. Cu recovery of 72% with EDTA at pH > 4.5. | High degree of recovery. Biodegradable nature of EDDS. | High consumption of chemicals. Non-biodegradable nature of EDTA. | [150] |

| Extraction with chelants: citric acid | Sewage sludge from WWTP | Heavy metals | Cu and Zn recoveries of 60%– 70% and 90%–100% at pH 3–4 with 0.1 M citric acid at 30 °C. | High recovery. Biodegradable nature of citric acid. | High consumption of chemicals. Acidic conditions. | [148] |

| Supported liquid membranes | Leaching effluents from sewage sludge | Heavy metals | Recovery of 27%, 22%, 30% and 32% for Cr, Cu, Ni and Zn using 20% Aliquat 336-filled PVDF membrane at 35 °C with 1.0 M HNO3. | Low costs. Simplicity. | Low recovery. Pre-treatment: removal of suspended solids. | [149] |

| Calcination with air or N2 using MgCl2 as additive | Secondary sludge from WWTP after dewatering | Heavy metals | Cu removal of 80% in air and 88% in N2 with Cl/sewage sludge ratio of 5%. Zn removal of 90% in air and N2 with a higher Cl/sewage sludge ratio (15%). | High recovery. | High costs. | [150] |