Transferrable Principles to Revolutionize Drinking Water Governance in First Nation Communities in Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Author Positionality

2.2. Study Location

2.3. Materials

3. Results

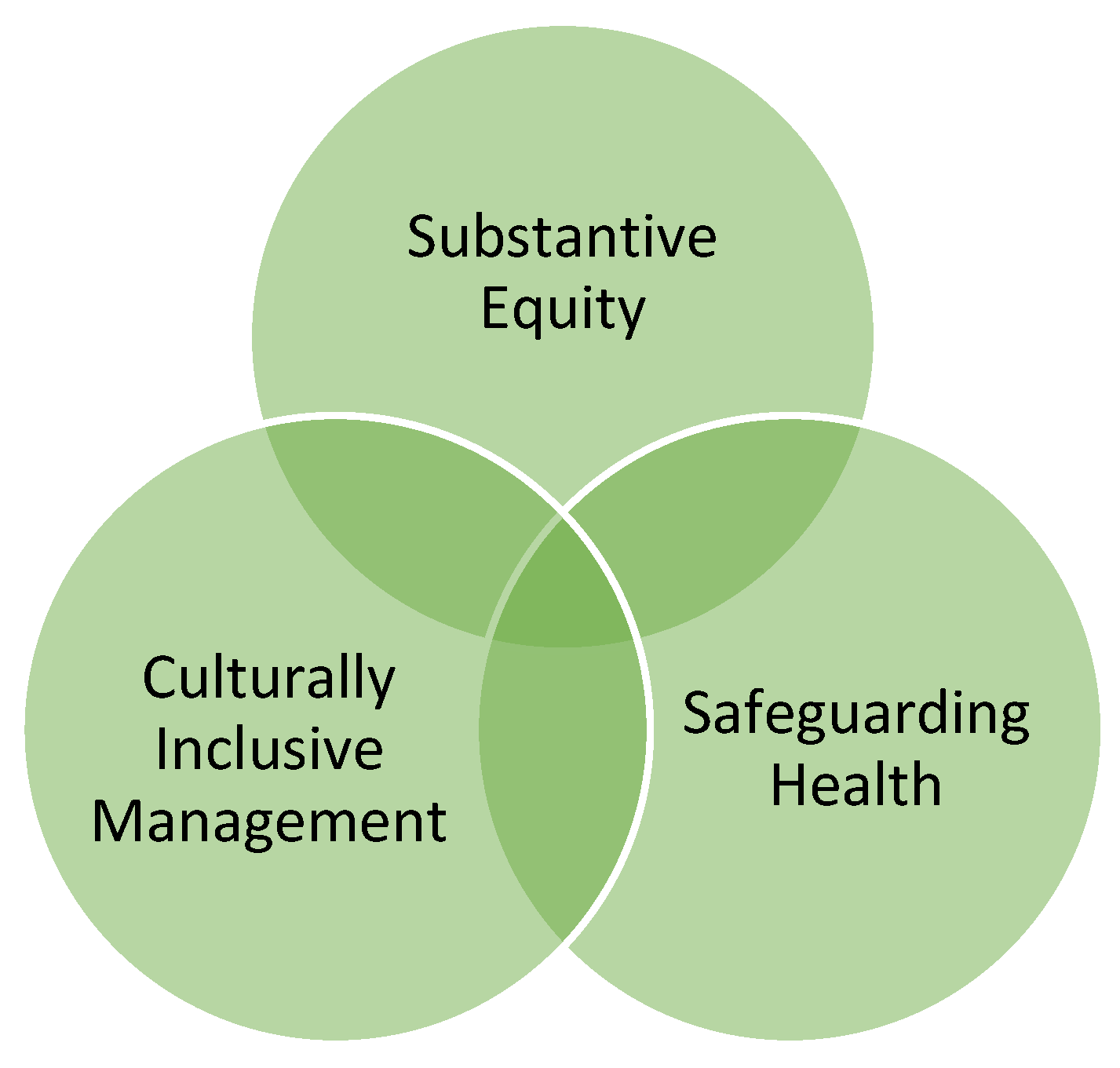

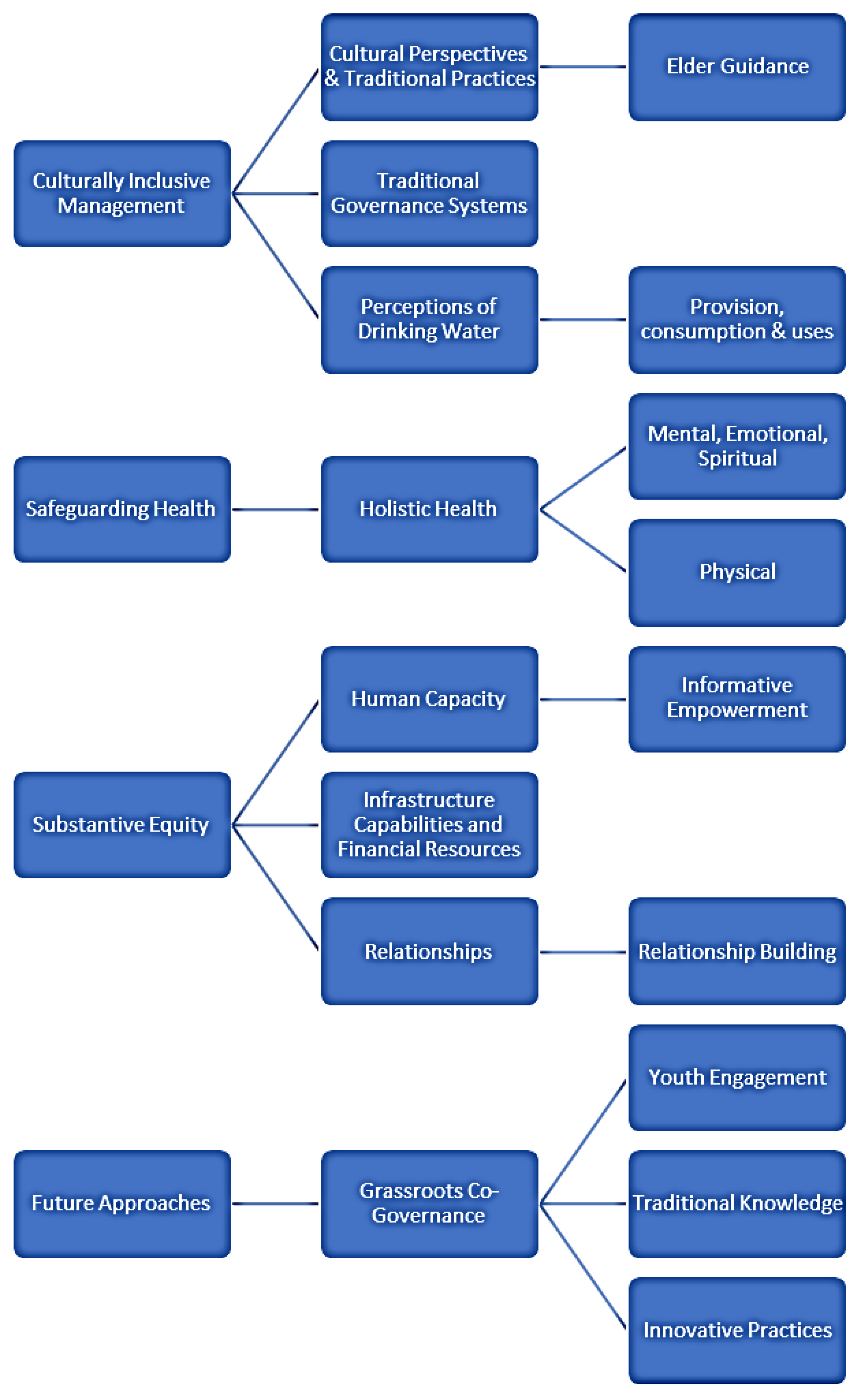

3.1. Culturally Inclusive Framework for First Nations Water Management

“I guess when you talk about water, when you lose that quality of water, you lose a quality of life, you know. And that’s what we’re losing. So our cul—when you say culture, it’s, um, it’s a struggle you make. Maybe the way the water is struggling, maybe that’s how we’re struggling. That’s part of our culture.”SL2

“They always told you one thing: Don’t play with water. And the other thing is um, don’t use it if you’re going to … or don’t use it if you’re going to make something good of it. Don’t throw it away if someone else can use it … Because once we get back to that Indigenous piece of sacredness of water, of spirit of water, of inherent right to water, who gave us this water, that’s all a part of this. And how can our next generation not be better because of it? And I’m not just talking First Nations people, I’m talking the Medicine Wheel and all races. So, we’re trying.”M1

“The use of the water, it’s not the same. So there’s definitely a shift from the traditional aspect of it to more modern and it’s because we’re not utilizing the … The social issue of it is it’s an erosion of who we are as Indian people. And ah now, no other, I always say, no other people in this world has changed or adapted from hunter/gatherer to state of the art technology within the span of 100 years. So that way of life is altered forever. It’s gone.”B2

“And it was meant for the purpose that you can’t live without it. Everybody has to have it. Animals, the whole world. Even ah, even the earth needed water to grow things.”CH3

“So when we talk about water, it’s interrelated to everything that we were back in the day … so you’re looking at how bugs are, how the frogs are, how the fliers are, how the four-legged are, and the two-legged and everything’s interconnected. And then you take away water out of that equation. What would live? Everything that doesn’t need water would still be okay.”M1

“Well, nobody owns water”B18

“Water … can’t be owned. It is ah, gifted to all things by the Creator and to try and own it is um, is wrong. To keep it away from another human being is wrong. To spoil it for another human being is wrong, but to spoil it for nature as well is wrong. Plants, animals, bugs, whatever uses it. If we spoil it, then we’re doing wrong.”M1

“The use of the water, it’s not the same. So there’s definitely a shift from the traditional aspect of it to more modern and it’s because we’re not utilizing the … The social issue of it is it’s an erosion of who we are as Indian people. And ah now, no other, I always say, no other people in this world has changed or adapted from hunter/gatherer to state of the art technology within the span of 100 years. So that way of life is altered forever. It’s gone.”B2

“And, uh, and then after that, when the water started not to get so—those ceremonies died down. I don’t know, for so long they didn’t have any ceremonies that much. And then they kind of revived and now they’re building again. So, yeah. Um, the language, too, where you don’t have your language, you don’t really have a culture. Now we’re using this Indian-English language, so that culture is kind of struggling. But this, in time, history, this area was a very popular place. A very clean and very pure place. Ceremonial ways. But now, today, it’s, uh, it’s a struggle. It’s a struggle.”SL2

“Because once we get back to that indigenous piece of sacredness of water, of spirit of water, of inherent right to water, who gave us this water, that’s all a part of this. And how can our next generation not be better because of it? And I’m not just talking First Nations people, I’m talking the Medicine Wheel and all races. So, we’re trying.”M1

“Well, my parents—well, my mum grew up, like—the—our parents grew up the traditional lifestyle. But even today, she doesn’t eat as much as the traditional foods’ cause she says there’s a funny taste to them now. That’s why they don’t really eat them. They think that they’re not good because of the water, the pollutants and all that.”CH2

“For instance, for me and what I’m learning in leadership and governance through my Elders is we had what was a family system … So if we had an issue in the community, I would get together with all my Bear Clan people and say “Here’s the issue and here’s our solution” and then the Buffalo Clan and the Raven Clan and the Beaver Clan and so on, would get together and they would say “Here’s our solution to our issue.” Then they would come together and say … the head men or the head people would get together and say “Here’s our solution to this issue.”SL1

“We had our people and they told us what to do. We had our societies and we go to the Elder society, we would go to the Women’s society and we would ask these questions. What should we do? We had spiritual people that helped us as well and if we didn’t have a physical answer for it, a physical plain answer for it, we actually went to ceremony to ask Creator. “Give us some guidance, give us some support … There are some people out there that won’t believe that everything has a spirit. Who won’t believe that fire has a spirit and water has a spirit and those types of things. We’re talking about Indigenous knowledge as well and we’re talking about things we don’t understand anymore.”M1

3.2. Safeguarding Health

“When the water declines, and then so do people”SL1

“I know my grandchildren, they go back home and their skin breaks out in a rash. We’ve said that many times but they insist it’s the operators putting in too much chlorine.”YQ2

“Yeah, we, most of us were getting, you know, our stomachs kept getting sick. You want to throw up and throw up, yeah. But we didn’t know it was from the water, cause I thought it was a flu going around, til they tested our water.”B16

“They’re tested and they are finding small percentages but it’s accumulations over time and depending on whether they consume more of it or bath in it. The amount that they’re using is, it varies.”B2

“Well, they think that the juice is healthy, but it’s not. It’s just a—because they don’t have—like, ’cause they can’t drink that water. So of course a lot of them just buy pop.”CH2

“Culturally, my elders tell us what you put in the water is getting you sick. That’s where all the cancer, arthritis, whatever, kidney problems, that’s what’s causing it. All the chemicals that you’re putting in the water.”SL1

“Like, uh, at home I don’t drink out of the tap. I don’t drink that. And I don’t trust it, you know. I don’t trust that water. I’d rather go get, uh, bottled water in town than drink that water.”SL2

“I think that’s the mentality we’re talking about. Um, the people have this mentality where they think the water is contaminated. They don’t trust it. And that affects everything: your health, your personal health, your emotions, your mental health and the spiritual side, there are a lot spiritualists here. Traditional spiritualists here who use water and they pray.”B2

“I feel that with this water, it’s been polluted and the true spirituality, sincerity, it’s been altered, affected. Like I said, it’s contaminated, polluted. There’s uneasiness. There’s no calm, there’s not purity. That’s the thing. And I can tell, based upon my own spirituality, I have a heavy, heavy heart. No matter what I do, no matter how hard I work, no matter how much I love my family, there’s this unsettling, uneasiness. It’s gnawing inside of me. I can’t do enough. I have to do more and more. There’s not enough.”B3

3.3. Substantive Equity

“Just like our wages. They’ve been saying the last three years they’re going to—they’re going to go up because they’re getting fed up of losing, um, operators from reserves. Reserves train the operators and the operators leave for the mines or everywhere else.”CH1

“We don’t know how much money’s going out, where that money’s going. We have a lot of land outside the reserve we had bought. Where that money’s going, I don’t know. Never anything done on this reserve.”B10

“Uh, I think it all comes down to budget, you know. Like we—like, we’d like to be more integrated into the budget. Because we—that’s one thing that comes up with INAC when we do our annual inspections every—that was one of the questions, are you directly involved with the budget? And we always say no. So we have no idea what our—What our budget is, what our limits are”CH1

“I believe the government has to be proactive in having better data and research for what’s being released upstream from us. To ensure that, of course, through drinking water, and umm...having like, regulations for underground water, surface water, and stuff like that, cuz I don’t know if underground water is safer or surface water, but we need regulations on both of them. It comes from somewhere and sooner or later it’s been tampered with by humans.”CH3

“So that’s kind of what I see happening is ah … the educating that has to keep taking place in order for us to maintain the water quality that’s there.”YQ18

“You’d have to … Every department would have to be included in it because you can’t enforce all these mechanisms without also educating your own people. Cause why spend money protecting and putting all these things in place when our people don’t know what it means.”B1

“Well, INAC—INAC contracts people—they put out a bid. Okay, I need a water treatment plant built, and then whoever can build it the cheapest, that’s who they give the contract to. And we’ve found, actually, there’s lots of—I usually get into this with the water treatment officer, but they, um—a lot of places, to make it cheap, will just use older parts from here and there, and they mix and match, and then when it’s time to actually find replacement parts, they can’t [laughs]. And it takes six months to ship something from somewhere in the States that—yeah, like, there’s a lot of—it’s outdated. Outdated parts, I guess, but in general, I suppose the treatment plants are just getting older.”CH2

“The majority of the parts I have are obsolete now. After maybe three or four years, they’re all obsolete.”SL3

“And also, you know, how long is the plant going to last? How long are, you know, with new technology that’s coming on board, we need to stay on top of that and we need to find out what costs are and ah, also the quality of the water itself. Like how is industry going to impact the underground water that we’re getting from? We don’t know that. When the contracts came in to build the plant, their main concern was to build the thing and move on. Didn’t look at the impacts of what would happen in case something did, or if it dried up or something.”YQ2

“Frogs and mice, you know, and that’s the reason why we don’t want to drink the water, yeah. Cause they never clean the cisterns. They say they do, but still I wouldn’t, I don’t drink it anymore.”B7

“Our Environmental Health Officer advised that we don’t drink from our cisterns cause they’re not clean or disinfected, and they’re supposed to be at least once a year. But some of us have gone quite a few years without it being cleaned, so we’re advised not to drink from it.”P1

“I don’t know, but umm … whatever happens with funding and all that, like it’s under wraps … there’s no transparency, or nothing happening, so, we don’t know what is for what, and what’s going to where … but that’s a different”LR2

“Look at us here. You—I—I know you were taken around to see how big our reserve is, I’m sure. Well, Health Canada still uses 1970s numbers for here. No kidding. 1970s population numbers is what they use. They’ve never updated. Like, right now we have over a thousand that live here. You know how many we had in the seventies? Less than a hundred. So that’s—those are the numbers they’re using, still in the seventies. ’Cause you can imagine how far back we are. We fight to try and get the numbers, like, brought up. But yeah, they’re—they’re still using numbers.”CH2

“It’s, we have the same problem here cuz, I, when I was a council member, I was the portfolio holder for Water and Sewer and you are exactly right when you say that. We had to dip into other pools of funds to get this part in because we didn’t, don’t have enough funding to offset a lot of these expenses. And in regards to parts, yeah, we encountered that problem. We had to, one occasion that I remember we had to get parts from Ontario. Yep. And we keep telling INAC people that they help us upgrade our water system here, but it’s not working.”CH3

“As keepers of the land and the sacredness that we hold to it. Land and water and whatnot, for them to understand, to have that philosophy. Ones that we hold dearly, but it’s not going to happen. They’ll still come there with … Everything that they propose, there’s always a plan already in place that doesn’t give us much room to … they’ll offer maybe a couple of instances where you, you know, have a voice but the big picture that’s, you know, it always happens. When something new comes down the pipe from Ottawa, we know there’s something in there already that’s not going to conform to what we want and that. It’s already set in stone. “Here, we’ll give you a chance to speak” but it’s very little that we have input in it. And I know our leaders are fighting, always for it and a lot of it does take money unfortunately. So yeah, everything that does come down, it’s already set in stone and we have to fight for whatever we want.”YQ2

4. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- First Nations Child and Family Caring Society. Available online: https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/jordans_principle_information_sheet_november_2018.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- Government of Canada. Available online: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1568396042341/1568396159824 (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- The Jordan’s Principle Working Group. Without Denial, Delay, or Disruption: Ensuring First Nations Children’s Access to Equitable Services through Jordan’s Principle. Available online: https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/jordans_principle-report.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Sinha, V.; Churchill, M. Reclaiming the Spirit of Jordan’s Principle: Lessons from a Canadian Human Rights Tribunal Ruling. Can. Rev. Soc. Policy 2018, 78, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock, C.; Prakash, T.; Loxley, J.; Wien, F. Wen:de: We Are Coming to the Light of Day. First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. Available online: https://cwrp.ca/publications/wende-we-are-coming-light-day (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- United Nations General Assembly. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 28 July 2010. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/64/292 (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Clean Water and Sanitation. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/water-and-sanitation/ (accessed on 23 August 2020).

- Government of Canada. Monthly Progress Update through October 2019 on Drinking Water Advisories on Public Systems on Reserves. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/news/2019/09/monthly-progress-update-through-august-2019-on-drinking-water-advisories-on-public-systems-on-reserves.html (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Government of Canada. Achieving a Sustainable Future: A Federal Sustainable Development Strategy for Canada. Available online: http://fsds-sfdd.ca/index.html#/en/detail/all/goal:G10 (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Government of Canada. Indian Act. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/ (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Wilson-Raybould, J. From Where I Stand: Rebuilding Indigenous Nations for a Stronger Canada; Purich Books: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2019; pp. 162–167. ISBN 978-0-7748-8053-4. [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous Services Canada. Water in First Nations Communities. Roles and Responsibilities. Available online: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1314034319353/1533665196191 (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- McGregor, D. Traditional Knowledge and Water Governance: The ethic of responsibility. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2014, 10, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phare, M. Denying the Source. The Crisis of First Nations Water Rights; Rocky Mountain Books: Surrey, BC, Canada, 2009; pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-897522-61-5. [Google Scholar]

- Odulaja, O.; Halesth, R. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and Indigenous Peoples in Canada. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. 2018. Available online: https://www.nccah-ccnsa.ca/docs/determinants/RPT-UN-SDG-IndPeoplesCanada-Halseth-Odulaja-EN.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Government of Canada. January 2020 Monthly Progress Update on Drinking Water Advisories on Public Systems on Reserve. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/news/2020/02/january-2020-monthly-progress-update-on-drinking-water-advisories-on-public-systems-on-reserves.html (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Post, Y.L.; McBean, E.; Gharabaghi, B. Using probabilistic neural networks to analyze First Nations’ drinking water advisory data. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2018, 144, 05018015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, R.; Diver, S.; McGregor, D.; Witham, A.; Bourassa, C. Shifting the Framework of Canadian Water Governance through Indigenous Research Methods: Acknowledging the Past with an Eye on the Future. Water 2018, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.P.; Murphy, L. Spence, N. Water and Indigenous peoples: Canada’s paradox. IIPJ Int. Indig. Pol. J. 2011, 3, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N. Querying water co-governance: Yukon First Nations and water governance in the context of modern land claim agreements. Water Altern. 2020, 13, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N.; Inkster, J. Respecting water: Indigenous water governance, ontologies, and the politics of kinship on the ground. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2018, 1, 516–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, E.; Yang, K.W. Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization Indig. Educ. Soc. 2012, 1, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. 2016 Census Topic: Aboriginal Peoples. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/rt-td/ap-pa-eng.cfm (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Statistics Canada. Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-PR-Eng.cfm?TOPIC=9&LANG=Eng&GK=PR&GC=47 (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Statistics Canada. Aboriginal Peoples: Fact Sheet for Saskatchewan. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-656-x/89-656-x2016009-eng.htm (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Statistics Canada. Saskatchewan Remains the Breadbasket of Canada. Farm and Farm Operator Data. 2017. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/ca2016 (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Newton, B. Saskatchewan River. In The Canadian Encyclopedia; 2017; Available online: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/saskatchewan-river (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Wheaton, E.; Nicolichuk, N. Patterns of Extreme Wet and Dry Hazards in the Canadian Prairie Provinces and Beyond. Available online: http://www.climateontario.ca/doc/APP/FuturePossibleDryAndWetExtremesInSaskatchewanCanada.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Government of Canada. The Canadian Drought Monitor. Available online: https://maps.canada.ca/journal/content-en.html?lang=en&appid=13f668fa9c944110b1ba30da2a49ff59&appidalt=0455430aee38469cb19d0eb057b42fb9 (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, K.; McKay, S. Water Song: Indigenous Women and Water. Solutions 2016, 7, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Latchmore, T.; Schuster-Wallace, C.; Longboat, D.; Dickson-Anderson, S.; Majury, A. Critical elements for local Indigenous water security in Canada: A narrative review. J. Water Health 2018, 16, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, R. Source water protection in a landscape of ‘New Era’ deregulation. Can. Geogr./Géogr. Can. 2009, 53, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diver, S.; Ahrens, D.; Arbit, T.; Bakker, K. Engaging Colonial Entanglements: “Treatment as a State” Policy for Indigenous Water Co-Governance. Glob. Environ. Politics 2019, 19, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longboat, S. First Nations Water Security: Security for Mother Earth. Can. Woman Stud. 2013, 30, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N. Indigenous water governance: Insights from the hydrosocial relations of the Koyukon Athabascan village of Ruby, Alaska. Geoforum 2014, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, W.; Taylor, B.; Kopnina, H.N.; Cryer, P.; Piccolo, J.J. Why ecocentrism is the key pathway to sustainability. Ecol. Citiz. 2017, 1, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, B. Things You May not Know about The Indian Act. Helping Canadians Make Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a Reality; Indigenous Relations Press: Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada, 2018; pp. 3–64. ISBN 978-0-9952665-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, D. Indigenous Processes of Consent: Through Legal Pluralism. Water 2019, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, L.E.; Bharadwaj, L.A.; Ovsenek, N. Indigenizing Water Governance in Canada. Glob. Issues Water Policy 2017, 7, 269–298. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, G.; Bakker, K.; Harris, L. Drinking Water Quality Guidelines across Canadian provinces and territories: Jurisdictional variation in the context of decentralized water governance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 4634–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, L.E.; Bharadwaj, L.; Okpalauwaekwe, U.; Waldner, C. Drinking water quality in Indigenous communities in Canada and health outcomes: A scoping review. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2016, 75, 32336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, H.; Stamler, L. Contemporary perceptions of health from an indigenous (Plains Cree) perspective. J. Natl. Aborig. Organ. 2010, 6, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality: Guideline Technical Document. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/healthy-living/guidelines-canadian-drinking-water-quality-guideline-technical-document-lead.html (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Mian, H.R.; Hu, G.; Hewage, K.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Sadiq, R. Prioritization of unregulated disinfection by-products in drinking water distribution systems for human health risk mitigation: A critical review. Water Res. 2018, 147, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Human. 2004. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono83.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Huang, L.; Wu, H.; Van Der Kuijp, T. The health effects of exposure to arsenic-contaminated drinking water: A review by global geographical distribution. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2015, 25, 432–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Jones, R.; Brender, J.; De Kok, T.; Weyer, P.; Nolan, B.; van Breda, S. Drinking Water Nitrate and Human Health: An Updated Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Kilfoy, B.; Weyer, P.; Anderson, K.; Folsom, A.; Cerhan, J. Nitrate Intake and the Risk of Thyroid Cancer and Thyroid Disease. Epidemiology 2010, 21, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.; Khalifa, M.; Sharaf, R. Contaminated water as a source of Helicobacter pylori infection: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wroblewski, L.E.; Peek, R.M., Jr.; Wilson, K.T. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: Factors that modulate disease risk. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 713–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldner, C.L.; Alimezelli, H.T.; Mcleod, L.; Zagozewski, R.; Bradford, L.E.; Bharadwaj, L. Self-reported Effects of Water on Health in First Nations Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada: Results from Community-Based Participatory Research. Environ. Health Insights 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucier, K.; Schuster-Wallace, C.; Skead, D.; Skead, K.; Dickson-Anderson, S. “Is there anything good about a water advisory”?: An Exploration of the Consequences of Drinking Water Advisories in an Indigenous Community. BMC Public Health J. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.; Lynch, K.; Cantillon, S.; Walsh, J. Equality: Putting the Theory into Action. Res. Publica 2006, 12, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. Reconceiving environmental justice: Global movements and political theories. Environ. Politics 2004, 13, 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szach, N. Keepers of the Water: Exploring Anishinaabe and Métis Women’s Knowledge of Water and Participation in Water Governance in Kenora, Ontario. Master’s Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2013. Available online: http://www.umanitoba.ca/institutes/natural_resources/Left-Hand%20Column/theses/Masters%20Thesis%20Penneys-Szach%202013.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Troian, M. Mi’kmaq Anti-Fracking Protest Brings Women to the Front Lines to Fight for Water. Available online: https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/mi-kmaq-anti-fracking-protest-brings-women-to-the-front-lines-to-fight-for-water-alK1jV5GE0Sa-gXWtatWwQ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Murphy, H.; Corston-Pine, E.; Post, Y.; McBean, E. Insights and Opportunities: Challenges of Canadian First Nations Drinking Water Operators. Int’l Indig. Pol. J. 2015, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boholm, A.; Prutzer, M. Experts’ understandings of drinking water risk management in a climate change scenario. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Deere, D.; Leusch, F.; Humpage, A.; Jenkins, M.; Cunliffe, D. Extreme weather events: Should drinking water quality management systems adapt to changing risk profiles? Water Res. 2015, 85, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, L.; Waldner, C.; Mclaughlin, K.; Zagozewski, R.; Bharadwaj, L. A mixed-method examination of risk factors in the truck-to-cistern drinking water system on the Beardy’s and Okemasis First Nation Reserve, Saskatchewan. Can. Water Resour. J./Rev. Can. Ressour. Hydr. 2018, 43, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Respondents | Role | Total Respondents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | |||

| Community 1 | 0 | 3 | Water treatment officer (1), public works supervisor (1), health services (1) | 3 |

| Community 2 | 1 | 2 | Water treatment operator (1), health services (1), executive officer (1) | 3 |

| Community 3 | 2 | 15 | Water treatment operator (1), Council member (1), Elder (15) | 17 |

| Community 4 | 12 | 6 | Documentation officer (1), community coordinator (1), water treatment operator (1), water treatment officer (1), Elder (14) | 18 |

| Community 5 | 2 | 6 | Management team (1), water treatment officer (1), public works manager (1), Elder (5) | 8 |

| Community 6 | 1 | 0 | Water treatment monitor | 1 |

| Community 7 | 0 | 3 | Health services (1), water treatment officer (1), Elder (1) | 3 |

| Total Participants (N) | 18 | 35 | 53 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Irvine, A.; Schuster-Wallace, C.; Dickson-Anderson, S.; Bharadwaj, L. Transferrable Principles to Revolutionize Drinking Water Governance in First Nation Communities in Canada. Water 2020, 12, 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12113091

Irvine A, Schuster-Wallace C, Dickson-Anderson S, Bharadwaj L. Transferrable Principles to Revolutionize Drinking Water Governance in First Nation Communities in Canada. Water. 2020; 12(11):3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12113091

Chicago/Turabian StyleIrvine, Alison, Corinne Schuster-Wallace, Sarah Dickson-Anderson, and Lalita Bharadwaj. 2020. "Transferrable Principles to Revolutionize Drinking Water Governance in First Nation Communities in Canada" Water 12, no. 11: 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12113091

APA StyleIrvine, A., Schuster-Wallace, C., Dickson-Anderson, S., & Bharadwaj, L. (2020). Transferrable Principles to Revolutionize Drinking Water Governance in First Nation Communities in Canada. Water, 12(11), 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12113091