1. Introduction

Drylands, defined as regions with an aridity index (the ratio of precipitation to potential evapotranspiration) of 0.65 or lower [

1], encompass approximately 40 percent of Earth’s terrestrial surface [

2]. These landscapes are characterized by chronic water scarcity and recurrent droughts. In such environments, rainfall is a limiting factor controlling vegetation dynamics and biogeochemical processes [

3,

4], thereby underscoring the importance of non-rainfall water inputs—such as dew, fog, and water-vapor adsorption [

5,

6]—which play critical roles in sustaining ecosystem functioning. Vegetation inhabiting these environments has evolved diverse physiological and morphological strategies to exploit non-rainfall water sources [

3]; for example,

Crassula species in the Namib Desert can absorb water through hydathodes [

7]. Non-rainfall water inputs can sometimes represent a significant component of the local water budget, influencing both water and energy fluxes [

8].

Dew forms when water vapor condenses on a surface that has cooled to or below the dew-point temperature [

8,

9]. Its formation depends on an intricate interplay of processes, including radiative surface cooling, longwave-radiation exchange between the land surface and the atmosphere, and heat and vapor transfer within soil and plant canopies [

10]. Atmospheric conditions, such as sky emissivity and ambient water vapor concentration, also govern cooling rates and the availability of moisture for condensation [

8,

11]. The balance among these factors determines the optimal conditions for dew development, which vary according to air temperature, cloud cover, and wind speed [

12,

13]. Under global-warming scenarios, dew formation is expected to decline; for instance, a 27 percent reduction in dew collection across the Mediterranean Basin is projected by 2080 [

14]. Similarly, in China’s Sanjiang Plain, sustained drying and warming trends have been shown to reduce dew formation in paddy ecosystems [

15]. Recent investigations continue to reveal both the decline and spatiotemporal variability of dew under changing climatic conditions. For example, Xu and Yan [

15] characterized dew processes in semi-arid regions of China, Zhuang and Zhao [

16] documented variations in oasis ecosystems, and Yu and Zhang [

17] analyzed global patterns of dew-moisture regimes in desert ecosystems. However, only a few studies have explicitly quantified dew formation using combined field observations and meteorological datasets over multiple years in hyperarid regions such as the Namib Desert.

Climate models predict an intensification of aridity, with severe droughts projected to affect regions such as Amazonia, the United States, and northern Africa, where the frequency of extreme drought events is expected to double by the end of this century [

18,

19]. However, regional manifestations of drought remain uncertain due to differences among climate-model projections and variations in drought definitions. Haile and Tang [

20] reviewed recent progress in understanding drought processes, emphasizing the necessity of linking non-rainfall water inputs such as dew to broader drought dynamics.

Despite a long history of dew observation, there remains no standardized method for quantifying dew [

21]. Advanced techniques such as microlysimeters can provide accurate measurements but are costly and labor-intensive [

22]. These methods are further constrained by their localized scope and inability to capture broader environmental variability [

5]. At the Gobabeb–Namib Research Institute, dew has been directly observed on both natural (soil) and artificial surfaces (metal plates and glass collectors). These complementary measurements enable assessment of condensation across different surface types and provide a robust basis for empirical model development.

Automated observation technologies have been increasingly adopted for measuring condensate water [

5,

23,

24]; however, such instruments are not always available in remote or resource-limited settings. Consequently, there remains a strong need for empirical modeling approaches based on widely available meteorological variables. In this study, the dew-point temperature (

T_d) was computed using the empirical formula

T_d =

T − ((100 −

RH)/5), in which the constants 100 and 5 are derived from the standard psychrometric relationship between air temperature and humidity under near-saturated conditions [

25]. Since surface-temperature data were unavailable, air temperature was used as a proxy, and a correction factor of −4 °C—determined through field calibration—was subtracted to improve realism. The calibration achieved 84.8% agreement with observed dew days, indicating that the correction effectively compensates for systematic temperature bias. While this correction may vary slightly among surface types or seasons, it provides a practical and transferable adjustment for other arid-region applications.

This study aims to develop a method for estimating dew formation using meteorological data and to evaluate the influence of climate change on dew occurrence in the Namib Desert over an eight-year period. The development of such a method is motivated by the demand for scalable and cost-effective techniques to monitor dew dynamics. Modeling dew formation using meteorological data provides a viable alternative, enabling spatially extensive predictions and continuous temporal assessments [

14]. Understanding trends in dew formation is essential for predicting moisture availability in arid regions and for assessing its implications for plant physiology, soil moisture dynamics, and overall ecosystem health.

The novelty of this study lies in the integration of direct dew observations with meteorological data to produce a validated empirical model for dew monitoring. In addition, this work separately evaluates morning and total dew frequencies to highlight diurnal asymmetries and the specific vulnerability of morning condensation to rising temperatures. By combining observation and modeling frameworks, this study contributes an improved, validated approach for assessing dew formation trends in data-scarce arid environments. This integrated framework combines accuracy and scalability, bridging the gap between localized, labor-intensive measurement techniques and broader-scale analytical assessments.

2. Materials and Methods

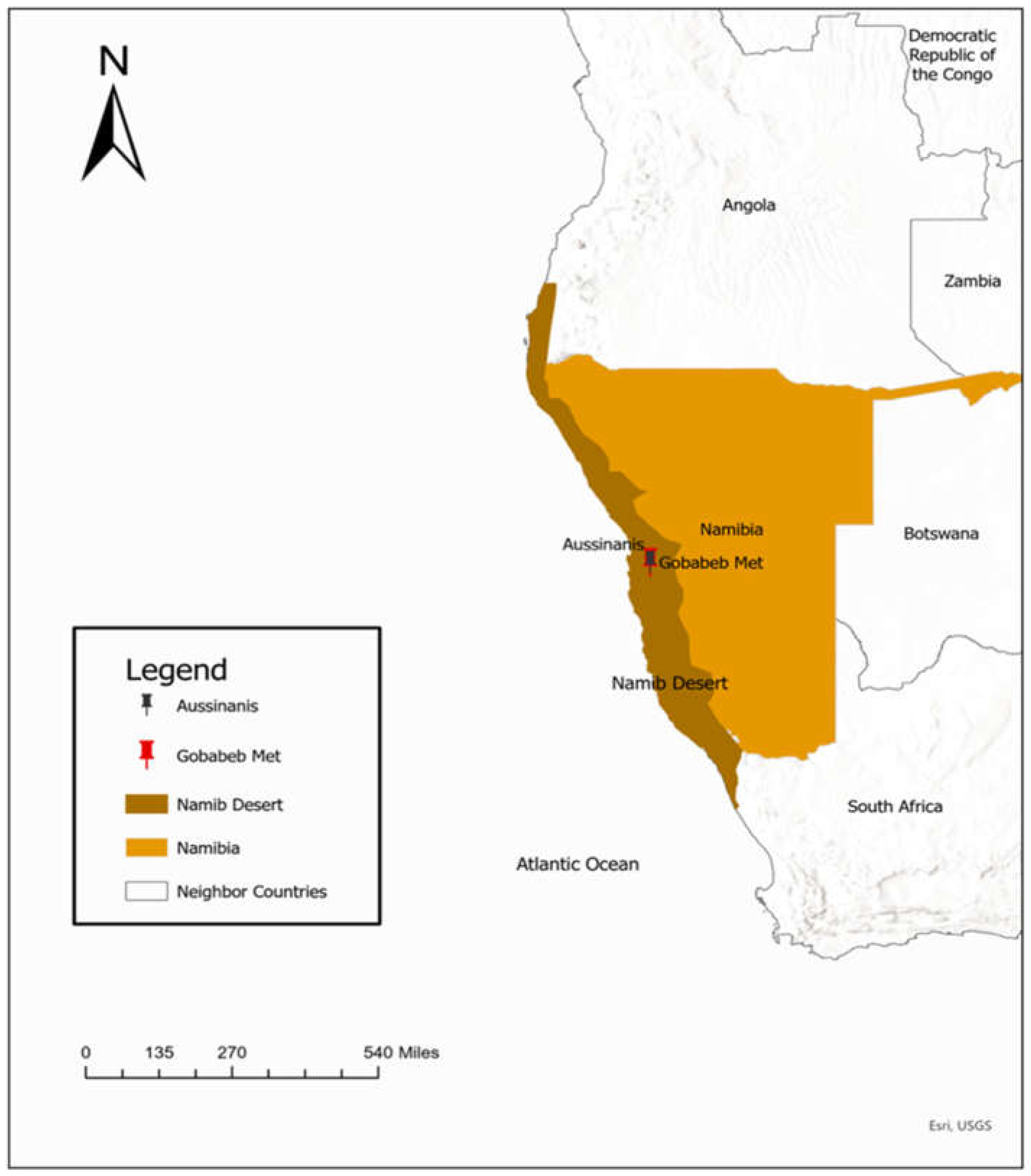

The arid western coastline of the southern African subcontinent experiences rainfall only infrequently (

Figure 1). The pronounced aridity of this region arises primarily from the subsidence of dry air associated with the global Hadley Circulation. A distinct northeast–southwest rainfall gradient spans southern Africa, transitioning from the semi-arid regions of the Kalahari and Karoo to the hyperarid Namib coast [

26].

Rainfall in this region exhibits pronounced spatial and temporal heterogeneity. The Namib area in central southern Africa, in particular, demonstrates considerable interannual and intra-annual variability in rainfall [

27]. Indeed, Namibian rainfall exhibits the highest coefficient of variation in southern Africa, with extreme fluctuations occurring in the central and northern portions of the Namib [

28]. Average annual precipitation ranges from 50 to 100 mm in the far south, 5 to 18 mm in the central Namib, and less than 50 mm along the Angolan coast to the north. Furthermore, rainfall increases from west to east—from approximately 10 mm at the coast to around 60 mm approximately 100 km inland [

29]—producing a steep yet spatially variable rainfall gradient extending from the desert interior to the Namibian highlands [

30].

This investigation was conducted in the Central Namib Desert (

Figure 1) at the Gobabeb Research Institute (latitude 23.56°, longitude 15.04°, elevation 405 m a.s.l.) [

31]. The Namib Desert is an extremely arid environment, receiving a mean annual rainfall of approximately 27 mm. It is located near the Tropic of Capricorn along the southwestern coast of Africa. Mean monthly temperatures at the site range from 17 to 24.2 °C, accompanied by an average relative humidity of 50% and an annual mean of 94 fog days [

30]. The Namib Desert extends from approximately 14° S to 32° S latitude and from 12° E to 16° E longitude, covering a distance of roughly 120 to 200 km inland from the coastal margin [

26]. June to November and December to May correspond to the dry and wet seasons at Gobabeb, respectively [

32]. The region experiences pronounced diurnal temperature cycles, often exceeding 20 °C differences between day and night, creating favorable conditions for nocturnal condensation and dew formation.

The northern section of Gobabeb is dominated by dunes, where the principal plant species include

Stipagrostis sabulicola and

Trianthema heroensis. The ephemeral Kuiseb River demarcates this area from the southern section, characterized by gravel plains dominated by

Zygophyllum simplex and

Z. stapffi [

33]. Our research utilized a field-based record of dew observations meticulously maintained at the Gobabeb Research Institute [

23]. Dew was measured using both natural and artificial condensation surfaces: natural soil plots of 1 m

2, aluminum collector plates (0.5 × 0.5 m), and the metal roof of the research facility, which provides a large uniform surface. Dew presence was visually and physically confirmed in the early morning hours (04:00–07:00 am local time) and recorded as a binary dew/no-dew observation. The frequency of observed dew was then compared with meteorological variables to calibrate the empirical model. However, most of the data used to estimate dew formation were obtained from the Southern African Science Service Centre for Climate and Adaptive Land Management (SASSCAL), a regional initiative providing comprehensive climate and environmental datasets across southern Africa. Hourly meteorological data from the Gobabeb Research Institute covering the period 2015–2022 were analyzed. For missing data, we incorporated observations from Aussinis (latitude 23.44°, longitude 15.04°, elevation 405 m a.s.l.), located within 10 km of Gobabeb (

Figure 1).

The dataset comprised essential meteorological variables relevant for estimating dew formation, including wind speed, wind direction, soil temperature, and air temperature. Relative humidity was obtained directly from the SASSCAL automatic weather station and expressed as hourly averages. All sensors were factory-calibrated, and accuracy levels were as follows: air temperature ±0.2 °C, soil temperature at 5 cm ±0.2 °C, relative humidity ±2%, and wind speed ±0.2 m s−1. Data gaps shorter than three hours were linearly interpolated, while longer gaps were filled using concurrent Aussinis records. The integration of site-specific data from Gobabeb with regional observations from SASSCAL provided a robust basis for analyzing the spatial and temporal patterns of dew formation in the Namib Desert. The meteorological instruments at Gobabeb maintained standard measurement accuracies: air temperature ±0.2 °C, soil temperature at 5 cm ±0.2 °C, relative humidity ±2%, and wind speed ±0.2 m s−1, ensuring dependable input data for dew estimation.

A new empirical method was developed to estimate the frequency of dew formation using the site’s meteorological data, which was subsequently validated through field observations. Field observations were conducted through multiple years using a metal dew collector, a car windshield collection, or a tin roof collection. Meteorological data for the period 2015–2022 were obtained from SASSCAL. The dew-point temperature (

T_d) was calculated using Equation (1) [

25]:

where

T_d represents the dew-point temperature,

T denotes surface temperature, and

RH indicates relative humidity [

25]. The constants 100 and 5 in this empirical relationship originate from the linearized psychrometric equation under moderate humidity conditions and have been widely used for first-order dew-point estimation. In this study, air temperature was used as a proxy for surface temperature because surface-temperature data were unavailable for the study area, and air temperature closely approximates surface temperature. However, using air temperature as a proxy produces a negative (

T_d −

T) value according to Equation (1), implying that all days exhibit air temperatures below the dew temperature. To rectify this, an empirically derived correction factor of −4 °C was introduced based on comparisons with field observations. Accordingly, air-temperature values were adjusted by subtracting 4 °C. This −4 °C offset was derived by minimizing misclassification error between modeled and observed dew days across 1200 hourly paired samples and yielded optimal performance; sensitivity tests showed that offsets between 3 °C and 5 °C produced less accurate predictions (accuracy ±3%). Although this correction factor may vary with prevailing meteorological conditions, the −4 °C adjustment provided the best fit for this dataset. While the correction was calibrated for Gobabeb conditions, the methodology allows recalibration for other stations, enhancing the universality of the approach.

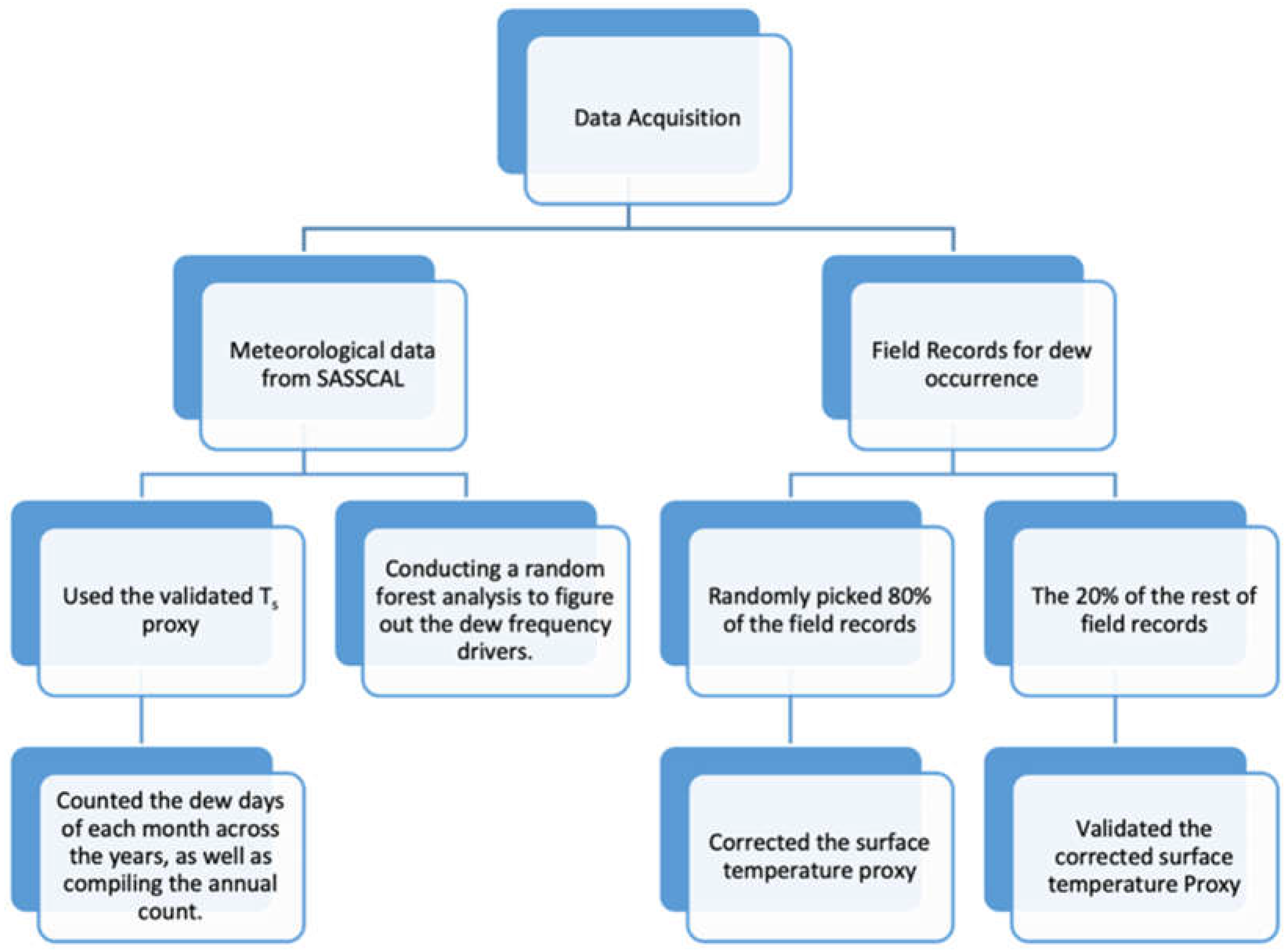

This correction was derived empirically from dew-formation observations recorded at the Gobabeb station. Eighty percent of the field dataset was used for calibration by applying the −4 °C correction to the air temperature, while the remaining 20 percent was used for validation. The resulting adjustment yielded an accuracy of 84.84%, correctly identifying dew days in the validation dataset. Using this validated correction factor, dew formation was estimated from hourly meteorological data, and dew days were subsequently enumerated based on the hourly dew results (

Figure 2). Model performance was further evaluated using correlation (r = 0.78,

p < 0.001) between observed and predicted dew frequencies, confirming robust predictive skill. In addition, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the influence of each variable (air temperature, soil temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed) on the probability of dew occurrence. This approach demonstrates that, while air temperature is an imperfect surrogate for surface temperature, careful correction produces reliable estimates. Nevertheless, the correction factor may vary across different surface types (e.g., dunes versus gravel plains) and between seasons (wet versus dry).

Annual dew days were counted for each year from 2015 to 2022 based on the hourly dew-formation calculations, and seasonal variations in dew occurrence were examined. Additionally, the relative importance of meteorological factors influencing dew formation was assessed using the random forest machine-learning algorithm. Random forest is an ensemble-learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during model training and aggregates their outputs to improve accuracy and reduce overfitting [

34]. In this study, the model consisted of 1000 decision trees, each trained on bootstrapped samples of the dataset. Predictor variables included air temperature, soil temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and wind direction. Variable importance was quantified using the Mean Decrease Impurity (MDI) index, which reflects each variable’s contribution to reducing classification error [

35]. The procedure was implemented in Python’s scikit-learn library (1.5.0), with 10-fold cross-validation to ensure model stability. The coefficient of determination (R

2) was calculated by comparing the variance explained by the model to the total variance of the dependent variable, thereby quantifying the proportion of dew-formation variability explained by the predictors. Values of R

2 approaching 1 indicate strong explanatory power [

36]. This analysis enabled a quantitative assessment of the relative contributions of soil temperature, air temperature, wind speed, wind direction, and humidity to the formation of dew.

3. Results

In this study, we quantified dew frequency using conventional meteorological measurements—an endeavor that traditionally requires extensive physical instrumentation. By strategically integrating a limited yet representative set of field-observed dew records with comprehensive meteorological datasets from the study site, we developed a novel approach to estimate the occurrence of dew days with an accuracy of 84.84%. This method significantly reduces reliance on labor-intensive field measurements while maintaining high precision in estimating dew occurrence. The findings demonstrate the potential of meteorological data as a reliable proxy for assessing dew frequency, thereby facilitating more efficient and accurate monitoring of dew patterns across a range of environmental settings. This methodological advancement is particularly relevant in arid and semi-arid regions where dew constitutes a critical component of the hydrological cycle and contributes to ecosystem sustainability. Model validation also showed a strong correlation between observed and predicted dew occurrence (r = 0.78, p < 0.001), confirming the reliability of the empirical approach across both calibration and validation subsets.

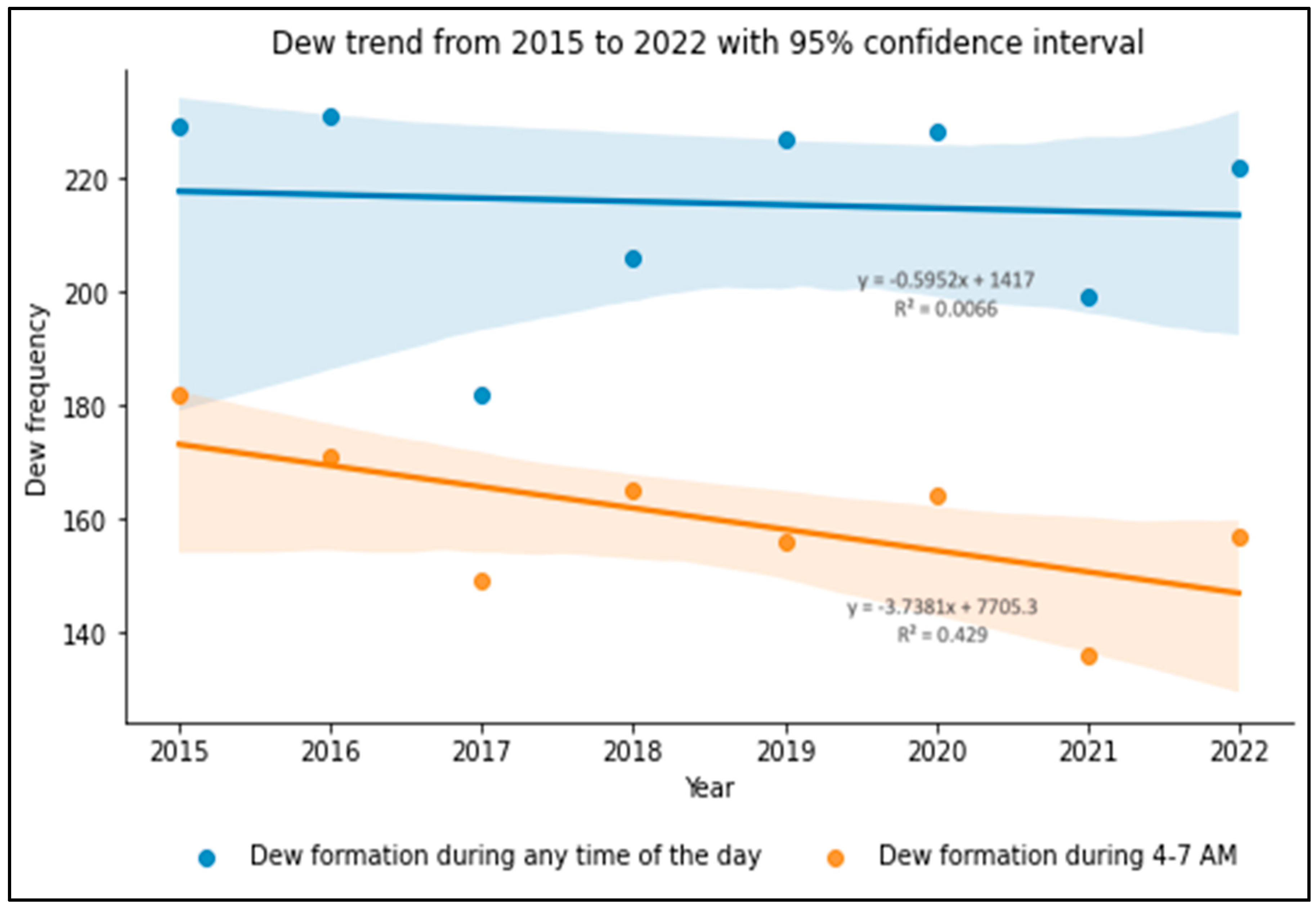

An analysis of seasonal variations revealed that dew formation was considerably more frequent during the wet season (December to May) than during the dry season (June to November) (

Figure 3). This observation aligns with expectations, as the wet season is typically characterized by elevated humidity, which increases the potential for dew condensation. Numerous studies have demonstrated that increased atmospheric moisture availability facilitates dew accumulation [

14]. In contrast, the dry season has low humidity and limited moisture, leading to a marked reduction in dew. Seasonal fluctuations in dew formation, therefore, represent a crucial aspect of the hydrological cycle in desert ecosystems, where dew serves as a vital moisture source for vegetation, soil biota, and surface-dwelling organisms. Quantitatively, the mean number of morning dew days during the wet season was 109 ± 6 days yr

−1, compared with only 55 ± 4 days yr

−1 in the dry season, confirming a nearly doubling in the wet season frequency.

A long-term analysis revealed a declining trend in the number of days with morning dew formation, raising concerns regarding the potential impacts of climate change on hydrological processes and ecosystem sustainability in hyperarid environments such as the Namib Desert. The annual number of dew days from 2015 to 2022 was 182, 171, 149, 165, 156, 164, 136, and 157, respectively. These data indicate an average decline of approximately 14% in annual morning dew formation over the study period. In contrast, the total number of days with any dew occurrence during a 24 h cycle remained relatively stable, suggesting that the observed decrease is specific to morning condensation events rather than overall dew potential. The year 2021 had the lowest dew frequency (136 days), which substantially contributed to the overall declining trend.

Figure 4 illustrates the interannual variability in dew occurrence from 2015 to 2022, with a clear, consistent downward trend. The linear regression slope for morning-dew frequency (−3.8 days yr

−1; R

2 = 0.43;

p < 0.05) confirms a statistically significant negative trend.

To further elucidate the drivers of this decline, we examined concurrent trends in key meteorological variables. Both mean annual air temperature and soil temperature increased slightly over the same period (by approximately +0.03 °C yr−1), while relative humidity exhibited a modest decrease (−0.26% yr−1). The negative correlation between morning-dew frequency and air temperature (r = −0.63) and the positive correlation with relative humidity (r = 0.71) support the hypothesis that warming and drying conditions are suppressing morning condensation.

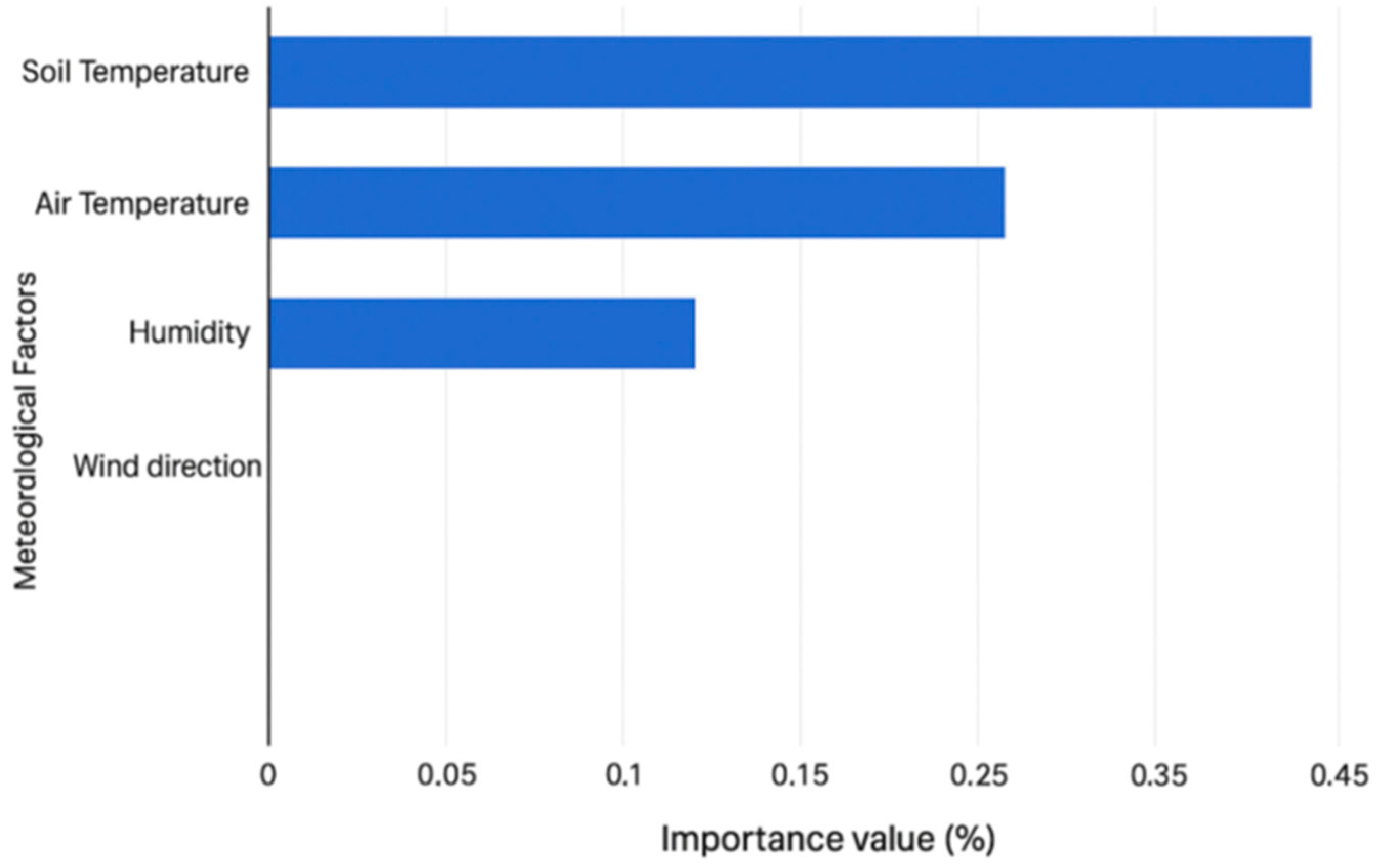

The random forest analysis (

Figure 5) identified soil temperature, air temperature, and relative humidity as the primary factors influencing dew formation in the Namib Desert. The negative correlation between rising temperature and dew occurrence aligns with the established understanding that higher temperatures accelerate evaporation and suppress condensation. Variable-importance scores indicated that soil temperature contributed 34% of the model variance, air temperature 28%, relative humidity 26%, and wind-related factors together accounted for less than 12%. This relationship underscores the sensitivity of dew formation to warming trends and highlights its potential vulnerability to ongoing climate change. Wind-related factors are often used in modeling dew formation [

37]. We did not find significant contributions of wind-related factors on dew formation at this site, highlighting the dominance of temperature and humidity on dew formation in this coastal location.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate a decline in morning dew formation in the Namib Desert from 2015 to 2022. This trend is consistent with broader expectations under global-warming scenarios, in which rising air and soil temperatures intensify evaporation, thereby reducing the potential for condensation. However, the overall number of days with dew at any time of day remained almost unchanged during the same period, indicating that the detected decline is largely confined to early-morning hours (04:00–07:00 am local time). This timing coincides with minimum nocturnal temperatures and peak radiative cooling; thus, even minor increases in nighttime temperature or decreases in humidity can suppress dew onset.

It is important to note that the eight-year observational record analyzed here does not satisfy the World Meteorological Organization’s recommended 30-year standard for defining climatological trends. Consequently, these findings should be interpreted as indicative of a short-term tendency rather than a definitive long-term climatic trajectory. The anomalously low dew frequency recorded in 2021 (136 days) contributed disproportionately to the downward trend, emphasizing the influence of interannual variability and the necessity for extended temporal datasets to establish robust climate-scale signals. Nevertheless, the accompanying meteorological data show consistent tendencies toward higher mean air and soil temperatures (+0.03 °C yr−1) and lower relative humidity (–0.26% yr−1) over 2015–2022, lending support to the interpretation that regional warming and drying are suppressing morning dew formation. Long-term (30–70 year) analyses from nearby coastal stations would be valuable to confirm whether these short-term variations are embedded within broader climate trends.

The application of a −4 °C correction factor to adjust air temperature as a proxy for surface temperature substantially improved model performance. Without this adjustment, the difference (T_d − T) would consistently appear negative, leading to the erroneous conclusion of continuous dew occurrence. Incorporating the correction enabled the model to achieve an overall accuracy of 84.8% when compared with field-based observations. However, this correction factor is unlikely to be universally applicable. This value depends on local energy balance, substrate thermal inertia, and atmospheric emissivity; for example, gravel plains with higher heat capacity may require smaller offsets than dune surfaces composed of fine sand. Sensitivity analysis confirmed that modifying the offset by ±1 °C changed the modeled dew frequency by about ±3%. Future studies should therefore treat the 4 °C correction as a site-specific calibration constant rather than a fixed global parameter. Variations in surface-energy balance between dunes and gravel plains, as well as seasonal differences between the wet and dry periods, may influence the optimal magnitude of this adjustment. Future studies should evaluate the model’s transferability across diverse surface conditions and climatic contexts.

The ecological implications of a decline in morning dew formation are profound. Dew constitutes a crucial non-rainfall water input in desert ecosystems, mitigating plant water stress, supporting insect survival, and stimulating microbial activity. Previous research has shown that dew moisture can activate microbial decomposition of surface litter [

33], thereby playing a key role in nutrient cycling. Because most biological activity in hyperarid systems occurs during the early morning when temperatures are mild and dew moisture is available, the loss of morning condensation may disproportionately reduce biotic functioning even if total daily dew frequency remains unchanged. A reduction in dew availability could therefore diminish decomposition rates, slow nutrient turnover, and intensify vegetation water stress—ultimately weakening the resilience of desert ecosystems under progressive climate change. Moreover, changes in dew timing can alter soil surface temperature profiles and nocturnal cooling rates, potentially affecting seed-germination microclimates and early seedling survival.

The principal innovation of this work lies in integrating meteorological observations with field-based dew records to produce a validated empirical model for dew estimation. This approach facilitates dew monitoring at sites where specialized equipment is unavailable, providing a scalable and cost-effective framework for hydrological research in arid and semi-arid environments. By combining direct observations from multiple condensation surfaces (soil, metal, and glass) with a data-driven model, the study bridges the gap between point-scale measurements and region-scale analyses. The random-forest results also reinforce the physical interpretation of the empirical model, showing that soil and air temperature jointly dominate dew-formation variability, followed by humidity. The developed framework thus provides a practical template for integrating short-term field records with long-term meteorological archives to track the sensitivity of non-rainfall moisture processes to climate change.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that, with an adequate quantity of field observations, it is possible to validate a new empirical method for estimating dew formation using meteorological data. The analysis reveals a measurable decline in dew formation in the Namib Desert between 2015 and 2022, identifying soil temperature, air temperature, and humidity as the principal variables influencing dew occurrence. In contrast, the total number of days with dew at any time of day remained nearly constant, indicating that the observed decrease is confined to early-morning condensation events rather than a general reduction in dew potential. The downward trend (−3.8 days yr−1; p < 0.05) corresponds closely with concurrent increases in air and soil temperature (+0.03 °C yr−1) and a decline in relative humidity (−0.26% yr−1), supporting the conclusion that regional warming and drying are key drivers of reduced morning dew frequency.

It is essential to emphasize that this observed decline represents a short-term tendency, as the eight-year dataset analyzed here does not meet the World Meteorological Organization’s 30-year standard for defining climatological trends. Nevertheless, the pattern provides an early indication of potential climate-driven reductions in dew formation. Future analyses extending over longer time spans and incorporating historical station records would help determine whether the current tendency reflects a persistent climatic trajectory or interannual variability.

Given the ecological importance of dew as a non-rainfall water source for plants, insects, and microbial communities, the decline in morning dew frequency may have significant implications for ecosystem resilience in the Namib Desert. Reduced dew inputs could intensify vegetation moisture stress, diminish microbial decomposition rates, and slow nutrient cycling, collectively weakening ecosystem functioning under continued climatic warming. Because most dew-dependent biological activity occurs during the early hours, even minor reductions in morning condensation can lead to disproportionate ecological effects.

The primary innovation of this study lies in the development of an empirically calibrated and validated model for monitoring dew formation. Unlike traditional approaches that require expensive and labor-intensive instrumentation, this framework relies on standard meteorological variables, rendering it both scalable and cost-effective. The −4 °C empirical correction applied to air temperature proved robust within the Namib dataset and provides a transferable methodological template that can be recalibrated for other arid and semi-arid regions. By integrating ground-based observations from multiple condensation surfaces with statistical modeling, the approach bridges fine-scale measurement and broader-scale climatic assessment, enabling future researchers to monitor non-rainfall moisture dynamics using long-term meteorological archives. Consequently, this approach can be applied to other arid and semi-arid ecosystems to evaluate non-rainfall water dynamics and assess their vulnerability to ongoing climate change.