Hereditary Polyneuropathies in the Era of Precision Medicine: Genetic Complexity and Emerging Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

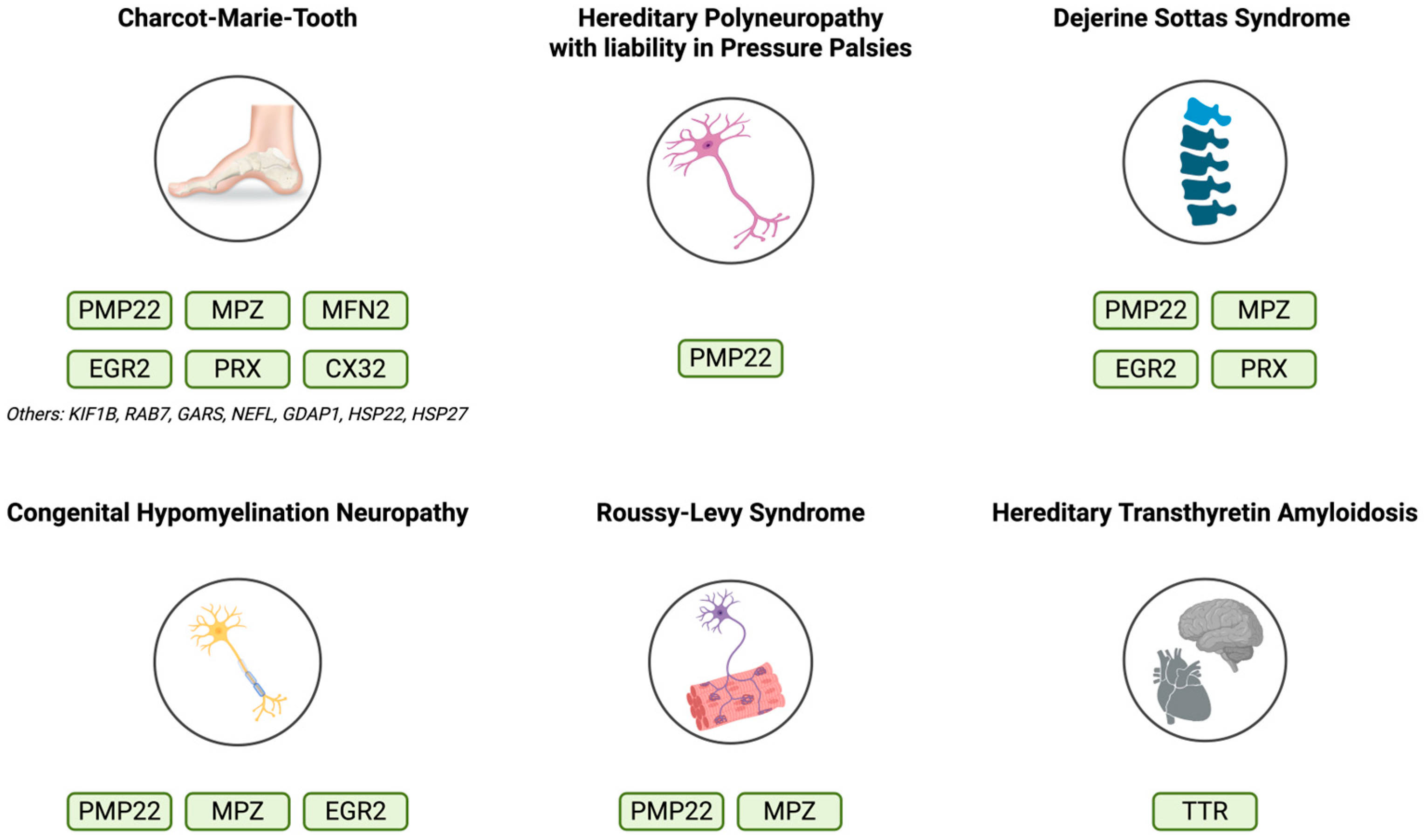

2. Genes Involved in HNPs

2.1. Peripheral Myelin Protein 22 Gene (PMP22)

2.1.1. Overview

2.1.2. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 1 (CMT1)

2.1.3. Hereditary Polyneuropathy with Liability in Pressure Palsies (HNPP)

2.1.4. Dejerine-Sottas Syndrome (DSS) and Congenital Hypomyelination Neuropathy (CHN)

2.1.5. Roussy–Levy Syndrome (RLS)

2.2. Myelin Protein Zero Gene (MPZ)

2.2.1. Overview

2.2.2. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1B (CMT1B)

2.2.3. Dejerine–Sottas Syndrome (DSS) and Congenital Hypomyelinating Neuropathy (CHN)

2.2.4. Roussy–Levy Syndrome (RLS)

2.3. Mitofusin 2 Gene (MFN2)

2.3.1. Overview

2.3.2. Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease Type 2 (CMT2)

2.4. Transthyretin (TTR)

2.4.1. Overview

2.4.2. Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hTTR)

2.5. Early Growth Response Protein 2 Gene (EGR2)

2.5.1. Overview

2.5.2. Dejerine- Sottas Syndrome (DSS) and Congenital Hypomyelination Neuropathy (CHN)

2.6. Periaxin Gene (PRX)

2.6.1. Overview

2.6.2. Dejerine-Sottas Syndrome (DSS)

2.6.3. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 4F (CMT4F)

2.7. Connexin 32 (CX32 or GJB1)

2.7.1. Overview

2.7.2. CMT1X-Linked Neuropathy

2.8. Other Genes Associated with HPNs

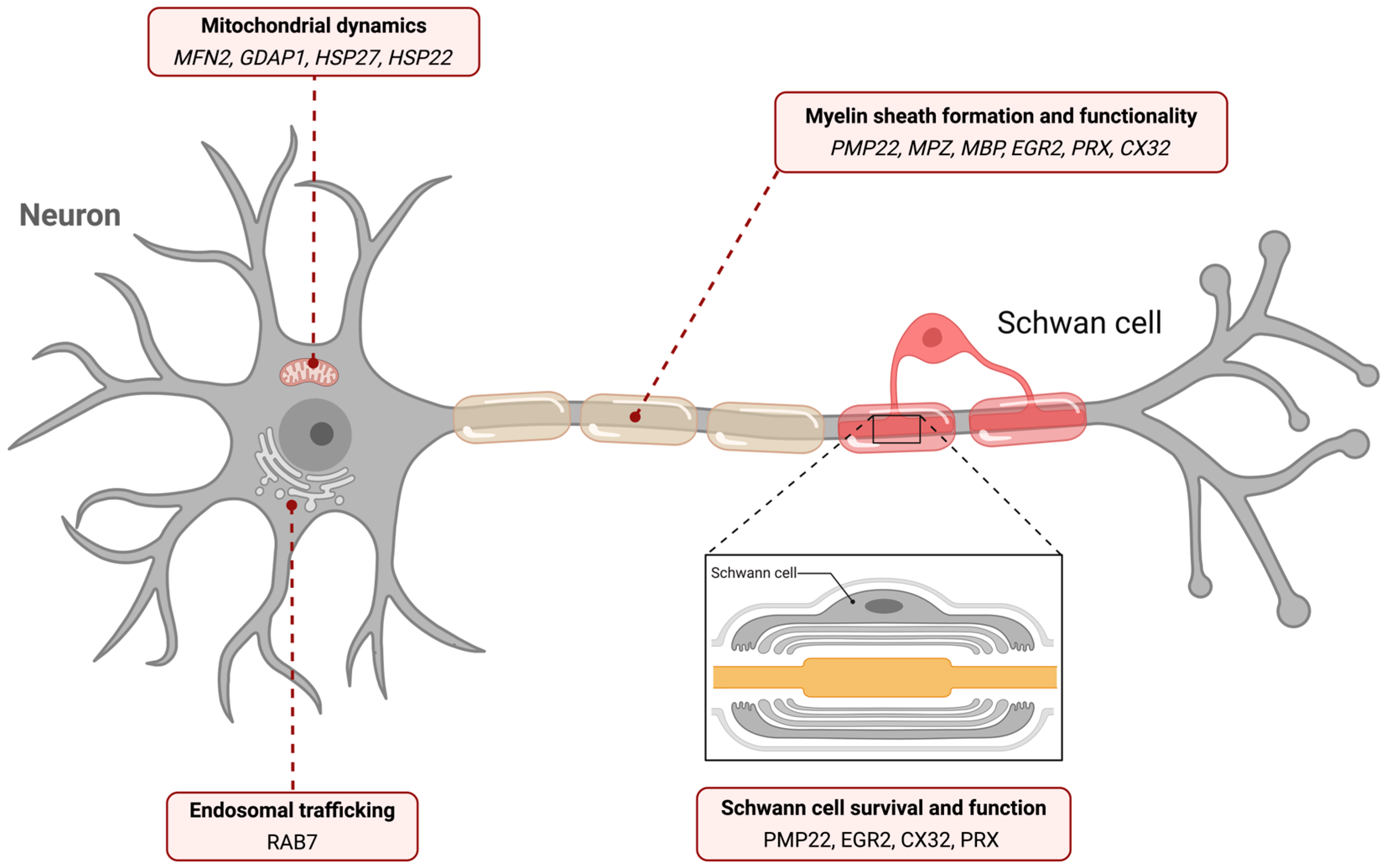

3. Gene-Linked Biological Pathways in the Pathogenesis of Hereditary Polyneuropathies

4. Treatment Approaches

4.1. Current Treatment

4.2. Research on Conservative Drugs

4.3. Advance on Precision Medicine in HPN Therapies

4.3.1. CMT1A Therapies

4.3.2. CMT2A Therapies

4.3.3. Neurotrophic Factors for Treatment; HGF, NT-3, BDNF

4.3.4. hATTR Therapies

4.3.5. Advances in Precision Diagnosis

4.3.6. General Considerations and Challenges

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAV | Adeno-associated viral |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AFO | Ankle foot orthoses |

| ARHGEF10 | Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 10 |

| ASOs | Antisense oligonucleotides |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CDRT15 | CMT1A duplicated region transcript 15 |

| CHN | Congenital hypomyelinating neuropathy |

| CMT | Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| Cx32 | Connexin 32 |

| DBD | DNA binding domain |

| DCTN1 | Dynactin subunit 1 |

| DSS | Dejerine–Sottas syndrome |

| EGR2 | Early growth response protein 2 |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| GARS | Glycyl-tRNA synthetase |

| GDAP1 | Ganglioside induced differentiation associated protein 1 |

| HGF | Human hepatocyte growth factor |

| HNPP | Hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies |

| HPNs | Hereditary polyneuropathies |

| HR | Heptad repeat region |

| HSP22 | Heat shock protein family B member 8 |

| HSP27 | Heat shock protein family B member 1 |

| HS3ST3B1 | Heparan sulfate-glucosamine 3-sulfotransferase 3B1 |

| hTTR | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis |

| KIF1B | Kinesin family member 1B |

| KO | Knockout |

| MAG | Myelin-associated glycoprotein |

| MBP | Myelin basic protein |

| MFN2 | Mitofusin 2 |

| MPZ | Myelin protein zero |

| NCV | Nerve conduction velocity |

| NEFL | Neurofilament light chain |

| NGFI-A | Nerve growth factor induced-A |

| NGFR | Nerve growth factor receptor |

| NGS | Next generation sequencing |

| ΝΤ-3 | Neurotrophin-3 |

| Pmcao | Permanent middle cerebral artery distal occlusion |

| PMP22 | Peripheral myelin protein 22 |

| PLS | Potocki–Lupski syndrome |

| PNS | Peripheral nervous system |

| PRX | Periaxin |

| RAB7 | Member of the RAS oncogene family |

| RLS | Roussy–Levy syndrome |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| SARM 1 | Sterile alpha and TIR motif containing 1 |

| SMS | Smith–Magenis syndrome |

| SNHI | Progressive sensorineural hearing impairment |

| TEKT4 | Tektin 4 |

| TTR | Transthyretin |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

References

- Kodal, L.S.; Duno, M.; Dysgaard, T. Clinical and Genetic Reassessment in Patients With Clinically Diagnosed Hereditary Polyneuropathy. Eur. J. Neurol. 2025, 32, e70301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callegari, I.; Gemelli, C.; Geroldi, A.; Veneri, F.; Mandich, P.; D’Antonio, M.; Pareyson, D.; Shy, M.E.; Schenone, A.; Prada, V.; et al. Mutation Update for Myelin Protein Zero-Related Neuropathies and the Increasing Role of Variants Causing a Late-Onset Phenotype. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 2629–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aberle, T.; Walter, A.; Piefke, S.; Hillgärtner, S.; Wüst, H.M.; Wegner, M.; Küspert, M. Sox10 Activity and the Timing of Schwann Cell Differentiation Are Controlled by a Tle4-Dependent Negative Feedback Loop. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermann, K.; Gess, B.; Häusler, M.; Weis, J.; Hahn, A.; Kurth, I. Hereditary Neuropathies. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 2018, 115, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustinx, M.; Shorrocks, A.-M.; Servais, L. Novel Therapeutic Approaches in Inherited Neuropathies: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupski, J.R.; Wise, C.A.; Kuwano, A.; Pentao, L.; Parke, J.T.; Glaze, D.G.; Ledbetter, D.H.; Greenberg, F.; Patel, P.I. Gene Dosage Is a Mechanism for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1A. Nat. Genet. 1992, 1, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupski, J.R. Genomic Disorders Ten Years On. Genome Med. 2009, 1, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braathen, G.J.; Sand, J.C.; Lobato, A.; Høyer, H.; Russell, M.B. Genetic Epidemiology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth in the General Population. Eur. J. Neurol. 2011, 18, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, C.O.; Rosenbaum, C.; Kupfer, S.; Wosch, S.; Stoegbauer, F.; Müller, H.W. Improved Culture Methods to Expand Schwann Cells with Altered Growth Behaviour from CMT1A Patients. Glia 1998, 23, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobbio, L.; Vigo, T.; Abbruzzese, M.; Levi, G.; Brancolini, C.; Mantero, S.; Grandis, M.; Benedetti, L.; Mancardi, G.; Schenone, A. Impairment of PMP22 Transgenic Schwann Cells Differentiation in Culture: Implications for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 1A Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004, 16, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Parker, B.; Martyn, C.; Natarajan, C.; Guo, J. The PMP22 Gene and Its Related Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 47, 673–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeymaekers, P.; Timmerman, V.; Nelis, E.; De Jonghe, P.; Hoogenduk, J.E.; Baas, F.; Barker, D.F.; Martin, J.J.; De Visser, M.; Bolhuis, P.A.; et al. Duplication in Chromosome 17p11.2 in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy Type 1a (CMT 1a). Neuromuscul. Disord. 1991, 1, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; Hall, S.M. Peripheral Demyelination and Remyelination Initiated by the Calcium-Selective Ionophore Ionomycin: In Vivo Observations. J. Neurol. Sci. 1988, 83, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, P. The Phenotypic Manifestations of Chromosome 17p11.2 Duplication. Brain 1997, 120, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrizi, G.M.; Cavallaro, T.; Taioli, F.; Orrico, D.; Morbin, M.; Simonati, A.; Rizzuto, N. Myelin Uncompaction in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy Type 1A with a Point Mutation of Peripheral Myelin Protein-22. Neurology 1999, 53, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambonini-Brugnoli, G.; Buchstaller, J.; Sommer, L.; Suter, U.; Mantei, N. Distinct Disease Mechanisms in Peripheral Neuropathies Due to Altered Peripheral Myelin Protein 22 Gene Dosage or a Pmp22 Point Mutation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005, 18, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saher, G.; Brügger, B.; Lappe-Siefke, C.; Möbius, W.; Tozawa, R.; Wehr, M.C.; Wieland, F.; Ishibashi, S.; Nave, K.-A. High Cholesterol Level Is Essential for Myelin Membrane Growth. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorour, E.; Upadhyaya, M. Mutation Analysis in Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease Type 1 (CMT1). Hum. Mutat. 1998, 8, S242–S247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palu, E.; Järvilehto, J.; Pennonen, J.; Huber, N.; Herukka, S.-K.; Haapasalo, A.; Isohanni, P.; Tyynismaa, H.; Auranen, M.; Ylikallio, E. Rare PMP22 Variants in Mild to Severe Neuropathy Uncorrelated to Plasma GDF15 or Neurofilament Light. Neurogenetics 2023, 24, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahenk, Z.; Chen, L.; Freimer, M. A Novel PMP22 Point Mutation Causing HNPP Phenotype. Neurology 1998, 51, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Dewar, K.; Katsanis, N.; Reiter, L.T.; Lander, E.S.; Devon, K.L.; Wyman, D.W.; Lupski, J.R.; Birren, B. The 1.4-Mb CMT1A Duplication/HNPP Deletion Genomic Region Reveals Unique Genome Architectural Features and Provides Insights into the Recent Evolution of New Genes. Genome Res. 2001, 11, 1018–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionasescu, V.V.; Ionasescu, R.; Searby, C.; Neahring, R. Dejerine-Sottas Disease with de Novo Dominant Point Mutation of the PMP22 Gene. Neurology 1995, 45, 1766–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyck, P.J.; Gomez, M.R. Segmental Demyelinization in Dejerine-Sottas Disease: Light, Phase-Contrast, and Electron Microscopic Studies. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1968, 43, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valentijn, L.J.; Ouvrier, R.A.; Van Den Bosch, N.H.A.; Bolhuis, P.A.; Baas, F.; Nicholson, G.A. Déjérine-Sottas Neuropathy Is Associated with a de Novo PMP22 Mutation. Hum. Mutat. 1995, 5, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabreëls-Festen, A. Dejerine–Sottas Syndrome Grown to Maturity: Overview of Genetic and Morphological Heterogeneity and Follow-up of 25 Patients. J. Anat. 2002, 200, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, W., Jr.; Neto, J.M.P.; Barreira, A.A. Dejerine–Sottas’ Neuropathy Caused by the Missense Mutation PMP22 Ser72Leu. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2004, 110, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, B.B.; Dyck, P.J.; Marks, H.G.; Chance, P.F.; Lupski, J.R. Dejerine–Sottas Syndrome Associated with Point Mutation in the Peripheral Myelin Protein 22 (PMP22) Gene. Nat. Genet. 1993, 5, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizi, G.M.; Simonati, A.; Taioli, F.; Cavallaro, T.; Ferrarini, M.; Rigatelli, F.; Pini, A.; Mostacciuolo, M.L.; Rizzuto, N. PMP22 Related Congenital Hypomyelination Neuropathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2001, 70, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabreëls-Festen, A.A.W.M.; Gabreëls, F.J.M.; Jennekens, F.G.I.; Janssen-van Kempen, T.W. The Status of HMSN Type III. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1994, 4, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelis, E.; Timmerman, V.; De Jonghe, P.; Vandenberghe, A.; Pham-Dinh, D.; Dautigny, A.; Martin, J.-J.; Van Broeckhoven, C. Rapid Screening of Myelin Genes in CMT1 Patients by SSCP Analysis: Identification of New Mutations and Polymorphisms in the P 0 Gene. Hum. Genet. 1994, 94, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.N.; Youssoufian, H. The CpG Dinucleotide and Human Genetic Disease. Hum. Genet. 1988, 78, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinter, J.; Lazzati, T.; Schmid, D.; Zeis, T.; Erne, B.; Lützelschwab, R.; Steck, A.J.; Pareyson, D.; Peles, E.; Schaeren-Wiemers, N. An Essential Role of MAG in Mediating Axon-Myelin Attachment in Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1A Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 49, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braathen, G.J. Genetic Epidemiology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2012, 126, iv-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, C.; Moll, C. Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies. J. Neurol. 1982, 228, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luigetti, M.; Del Grande, A.; Conte, A.; Lo Monaco, M.; Bisogni, G.; Romano, A.; Zollino, M.; Rossini, P.M.; Sabatelli, M. Clinical, Neurophysiological and Pathological Findings of HNPP Patients with 17p12 Deletion: A Single-Centre Experience. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 341, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariman, E.C.M.; Gabreëls-Festen, A.A.W.M.; van Beersum, S.E.C.; Jongen, P.J.H.; Ropers, H.-H.; Gabreëls, F.J.M. Gene for Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies (HNPP) Maps to Chromosome 17 at or Close to the Locus for HMSN Type 1. Hum. Genet. 1993, 92, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, K.J.; Leicher, C.R.; DiMario, F.J. Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies in Children. Pediatr. Neurol. 1999, 21, 818–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karklinsky, S.; Kugler, S.; Bar-Yosef, O.; Nissenkorn, A.; Grossman-Jonish, A.; Tirosh, I.; Vivante, A.; Pode-Shakked, B. Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies (HNPP): Intrafamilial Phenotypic Variability and Early Childhood Refusal to Walk as the Presenting Symptom. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J.G.Y. About families with hereditary disposition to the development of neuritides, correlated with migraine. Monatsschrift Psychiatr. Neurol. 1947, 50, 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen, W.I.M.; Huygen, P.L.M.; Gabreëls-Festen, A.a.W.M.; Engelhart, M.; van Mierlo, P.J.W.B.; van Engelen, B.G.M. Sensorineural Hearing Impairment in Patients with Pmp22 Duplication, Deletion, and Frameshift Mutations. Otol. Neurotol. 2005, 26, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrestian, N.; McMillan, H.; Poulin, C.; Campbell, C.; Vajsar, J. Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies in Childhood: Case Series and Literature Update. Neuromuscul. Disord. NMD 2015, 25, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, G.A.; Valentijn, L.J.; Cherryson, A.K.; Kennerson, M.L.; Bragg, T.L.; DeKroon, R.M.; Ross, D.A.; Pollard, J.D.; Mcleod, J.G.; Bolhuis, P.A.; et al. A Frame Shift Mutation in the PMP22 Gene in Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies. Nat. Genet. 1994, 6, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.K.; Hurvitz, E.A. Peripheral Neuropathy: A True Risk Factor for Falls. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 1995, 50, M211–M215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harati, Y.; Butler, I.J. Congenital Hypomyelinating Neuropathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1985, 48, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.P.; Warner, L.E.; Lupski, J.R.; Garg, B.P. Congenital Hypomyelinating Neuropathy: Two Patients with Long-Term Follow-Up. Pediatr. Neurol. 1999, 20, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, L.E.; Hilz, M.J.; Appel, S.H.; Killian, J.M.; Kolodny, E.H.; Karpati, G.; Carpenter, S.; Watters, G.V.; Wheeler, C.; Witt, D.; et al. Clinical Phenotypes of Different MPZ (P0) Mutations May Include Charcot–Marie–Tooth Type 1B, Dejerine–Sottas, and Congenital Hypomyelination. Neuron 1996, 17, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschwind, M.D.; Haman, A.; Miller, B.L. Rapidly Progressive Dementia. Neurol. Clin. 2007, 25, 783-vii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau, F.; Löfgren, A.; Jonghe, P.D.; Bort, S.; Nelis, E.; Sevilla, T.; Martin, J.-J.; Vilchez, J.; Prieto, F.; Broeckhoven, C.V. Origin of the de Novo Duplication in Charcot—Marie—Tooth Disease Type 1A: Unequal Nonsister Chromatid Exchange during Spermatogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993, 2, 2031–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelschlager, R.; White, H.H.; Schimke, R.N. Roussy-Lévy Syndrome: Report of a Kindred and Discussion of the Nosology. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1971, 47, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Harel, T.; Gu, S.; Liu, P.; Burglen, L.; Chantot-Bastaraud, S.; Gelowani, V.; Beck, C.R.; Carvalho, C.M.B.; Cheung, S.W.; et al. Nonrecurrent 17p11.2p12 Rearrangement Events That Result in Two Concomitant Genomic Disorders: The PMP22-RAI1 Contiguous Gene Duplication Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 97, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planté-Bordeneuve, V.; Guiochon-Mantel, A.; Lacroix, C.; Lapresle, J.; Said, G. The Roussy-Lévy Family: From the Original Description to the Gene. Ann. Neurol. 1999, 46, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, E.; Gioiosa, V.; Serrao, M.; Casali, C. Roussy-Lévy Syndrome: A Case of Genotype–Phenotype Correlation. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 4357–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, L.; Doyle, J.P.; Hensley, P.; Colman, D.R.; Hendrickson, W.A. Crystal Structure of the Extracellular Domain from P0, the Major Structural Protein of Peripheral Nerve Myelin. Neuron 1996, 17, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, G.; Lamar, E.; Patterson, J. Isolation and Analysis of the Gene Encoding Peripheral Myelin Protein Zero. Neuron 1988, 1, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raasakka, A.; Kursula, P. How Does Protein Zero Assemble Compact Myelin? Cells 2020, 9, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashkova, N.; Peterson, T.; Ptak, C.; Winistorfer, S.; Guerrero-Given, D.; Kamasawa, N.; Ahern, C.; Shy, M.; Piper, R. PMP22 Associates with MPZ via Their Transmembrane Domains and Disrupting This Interaction Causes a Loss-of-Function Phenotype Similar to Hereditary Neuropathy Associated with Liability to Pressure Palsies (HNPP). iScience 2024, 27, 110989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirano, R.I.; Goerich, D.E.; Riethmacher, D.; Wegner, M. Protein Zero Gene Expression Is Regulated by the Glial Transcription Factor Sox10. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 3198–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shy, M.E.; Jáni, A.; Krajewski, K.; Grandis, M.; Lewis, R.A.; Li, J.; Shy, R.R.; Balsamo, J.; Lilien, J.; Garbern, J.Y.; et al. Phenotypic Clustering in MPZ Mutations. Brain 2004, 127, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, M.J.; Sternberger, N.; Ederle, K.; Spencer, P.S. Studies on the Control of Myelinogenesis. IV. Neuronal Induction of Schwann Cell Myelin-Specific Protein Synthesis during Nerve Fiber Regeneration. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 1982, 2, 1252–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattin, A.-L.; Burden, J.J.; Van Emmenis, L.; Mackenzie, F.E.; Hoving, J.J.A.; Garcia Calavia, N.; Guo, Y.; McLaughlin, M.; Rosenberg, L.H.; Quereda, V.; et al. Macrophage-Induced Blood Vessels Guide Schwann Cell-Mediated Regeneration of Peripheral Nerves. Cell 2015, 162, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamholz, J.; Menichella, D.; Jani, A.; Garbern, J.; Lewis, R.A.; Krajewski, K.M.; Lilien, J.; Scherer, S.S.; Shy, M.E. Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease Type 1: Molecular Pathogenesis to Gene Therapy. Brain 2000, 123, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneri, F.A.; Prada, V.; Mastrangelo, R.; Ferri, C.; Nobbio, L.; Passalacqua, M.; Milanesi, M.; Bianchi, F.; Del Carro, U.; Vallat, J.-M.; et al. A Novel Mouse Model of CMT1B Identifies Hyperglycosylation as a New Pathogenetic Mechanism. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2022, 31, 4255–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shy, M.E. Peripheral Neuropathies Caused by Mutations in the Myelin Protein Zero. J. Neurol. Sci. 2006, 242, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, X.; Brennan, K.M.; Wang, D.S.; D’Antonio, M.; Moran, J.; Svaren, J.; Shy, M.E. Myelin Protein Zero Mutations and the Unfolded Protein Response in Charcot Marie Tooth Disease Type 1B. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2018, 5, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, M.; Suehara, M.; Saito, A.; Takashima, H.; Umehara, F.; Saito, M.; Kanzato, N.; Matsuzaki, T.; Takenaga, S.; Sakoda, S.; et al. A Novel MPZ Gene Mutation in Dominantly Inherited Neuropathy with Focally Folded Myelin Sheaths. Neurology 1999, 52, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, T.; Nicholson, G.; Ikeda, H.; Ishida, A.; Johnston, H.; Wise, G.; Ouvrier, R.; Hayasaka, K. De Novo Mutation of the Myelin Po Gene in Déjérine-Sottas Disease (Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathy Type III): Two Amino Acid Insertion after Asp 118. Hum. Mutat. 1998, 11, S103–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, T.; Nicholson, G.; Ikeda, H.; Ishida, A.; Johnston, H.; Wise, G.; Ouvrier, R.; Hayasaka, K. A Novel Homozygous Mutation of the Myelin Po Gene Producing Dejerine-Sottas Disease (Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathy Type III). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 222, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrabetz, L.; D’Antonio, M.; Pennuto, M.; Dati, G.; Tinelli, E.; Fratta, P.; Previtali, S.; Imperiale, D.; Zielasek, J.; Toyka, K.; et al. Different Intracellular Pathomechanisms Produce Diverse Myelin Protein Zero Neuropathies in Transgenic Mice. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 2358–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Khajavi, M.; Ohyama, T.; Hirabayashi, S.; Wilson, J.; Reggin, J.D.; Mancias, P.; Butler, I.J.; Wilkinson, M.F.; Wegner, M.; et al. Molecular Mechanism for Distinct Neurological Phenotypes Conveyed by Allelic Truncating Mutations. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanmaneechai, O.; Feely, S.; Scherer, S.S.; Herrmann, D.N.; Burns, J.; Muntoni, F.; Li, J.; Siskind, C.E.; Day, J.W.; Laura, M.; et al. Genotype-Phenotype Characteristics and Baseline Natural History of Heritable Neuropathies Caused by Mutations in the MPZ Gene. Brain J. Neurol. 2015, 138, 3180–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saporta, A.S.D.; Sottile, S.L.; Miller, L.J.; Feely, S.M.E.; Siskind, C.E.; Shy, M.E. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Subtypes and Genetic Testing Strategies. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saporta, M.A.C.; Shy, B.R.; Patzko, A.; Bai, Y.; Pennuto, M.; Ferri, C.; Tinelli, E.; Saveri, P.; Kirschner, D.; Crowther, M.; et al. MpzR98C Arrests Schwann Cell Development in a Mouse Model of Early-Onset Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1B. Brain J. Neurol. 2012, 135, 2032–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.; Feely, S.M.E.; Grider, T.; Bacha, A.; Scarlato, M.; Fazio, R.; Quattrini, A.; Shy, M.E.; Previtali, S.C. Loss of Function MPZ Mutation Causes Milder CMT1B Neuropathy. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2021, 26, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrou, M.; Sargiannidou, I.; Georgiou, E.; Kagiava, A.; Kleopa, K.A. Emerging Therapies for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Inherited Neuropathies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCulloch, M.K.; Mehryab, F.; Rashnonejad, A. Navigating the Landscape of CMT1B: Understanding Genetic Pathways, Disease Models, and Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagueny, A.; Latour, P.; Vital, A.; Rajabally, Y.; Le Masson, G.; Ferrer, X.; Bernard, I.; Julien, J.; Vital, C.; Vandenberghe, A. Peripheral Myelin Modification in CMT1B Correlates with MPZ Gene Mutations. Neuromuscul. Disord. NMD 1999, 9, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Züchner, S.; Mersiyanova, I.V.; Muglia, M.; Bissar-Tadmouri, N.; Rochelle, J.; Dadali, E.L.; Zappia, M.; Nelis, E.; Patitucci, A.; Senderek, J.; et al. Mutations in the Mitochondrial GTPase Mitofusin 2 Cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy Type 2A. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 449–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-J.; Cao, Y.-L.; Feng, J.-X.; Qi, Y.; Meng, S.; Yang, J.-F.; Zhong, Y.-T.; Kang, S.; Chen, X.; Lan, L.; et al. Structural Insights of Human Mitofusin-2 into Mitochondrial Fusion and CMT2A Onset. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detmer, S.A.; Chan, D.C. Complementation between Mouse Mfn1 and Mfn2 Protects Mitochondrial Fusion Defects Caused by CMT2A Disease Mutations. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 176, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Hu, J. Mitochondrial Fusion: The Machineries In and Out. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, D.; Pich, S.; Soriano, F.X.; Vega, N.; Baumgartner, B.; Oriola, J.; Daugaard, J.R.; Lloberas, J.; Camps, M.; Zierath, J.R.; et al. Mitofusin-2 Determines Mitochondrial Network Architecture and Mitochondrial Metabolism. A Novel Regulatory Mechanism Altered in Obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 17190–17197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pich, S.; Bach, D.; Briones, P.; Liesa, M.; Camps, M.; Testar, X.; Palacín, M.; Zorzano, A. The Charcot–Marie–Tooth Type 2A Gene Product, Mfn2, up-Regulates Fuel Oxidation through Expression of OXPHOS System. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, E.A.; Manfredi, G. Neuronal Degeneration and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, A.; Li, J.; Kelly, D.P.; Hershberger, R.E.; Marian, A.J.; Lewis, R.M.; Song, M.; Dang, X.; Schmidt, A.D.; Mathyer, M.E.; et al. A Human Mitofusin 2 Mutation Can Cause Mitophagic Cardiomyopathy. eLife 2023, 12, e84235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrizaila, N.; Samulong, S.; Tey, S.; Suan, L.C.; Meng, L.K.; Goh, K.J.; Ahmad-Annuar, A. X-Linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Predominates in a Cohort of Multiethnic Malaysian Patients. Muscle Nerve 2014, 49, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, A.V.; Rebelo, A.P.; Zhang, F.; Price, J.; Bolon, B.; Silva, J.P.; Wen, R.; Züchner, S. Characterization of the Mitofusin 2 R94W Mutation in a Knock-in Mouse Model. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2014, 19, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, K.; Claeys, K.G.; Züchner, S.; Schröder, J.M.; Weis, J.; Ceuterick, C.; Jordanova, A.; Nelis, E.; De Vriendt, E.; Van Hul, M.; et al. MFN2 Mutation Distribution and Genotype/Phenotype Correlation in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 2. Brain J. Neurol. 2006, 129, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Wang, Z.; Gao, C.; Yang, L.; Li, M.; Tang, X.; Yuan, H.; Pang, D.; Ouyang, H. Mfn2R364W, Mfn2G176S, and Mfn2H165R Mutations Drive Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 2A Disease by Inducing Apoptosis and Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation Damage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Kitsis, R.N.; Fleischer, J.A.; Gavathiotis, E.; Kornfeld, O.S.; Gong, G.; Biris, N.; Benz, A.; Qvit, N.; Donnelly, S.K.; et al. Correcting Mitochondrial Fusion by Manipulating Mitofusin Conformations. Nature 2016, 540, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, A.G.; Franco, A.; Krezel, A.M.; Rumsey, J.M.; Alberti, J.M.; Knight, W.C.; Biris, N.; Zacharioudakis, E.; Janetka, J.W.; Baloh, R.H.; et al. MFN2 Agonists Reverse Mitochondrial Defects in Preclinical Models of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 2A. Science 2018, 360, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, A.; Walton, C.E.; Dang, X. Mitochondria Clumping vs. Mitochondria Fusion in CMT2A Diseases. Life 2022, 12, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemignani, F.; Marbini, A. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease (CMT): Distinctive Phenotypic and Genotypic Features in CMT Type 2. J. Neurol. Sci. 2001, 184, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, J.M. Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathies. J. Med. Genet. 1991, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feely, S.M.E.; Laura, M.; Siskind, C.E.; Sottile, S.; Davis, M.; Gibbons, V.S.; Reilly, M.M.; Shy, M.E. MFN2 Mutations Cause Severe Phenotypes in Most Patients with CMT2A. Neurology 2011, 76, 1690–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionasescu, V.; Searby, C.; Sheffield, V.C.; Roklina, T.; Nishimura, D.; Ionasescu, R. Autosomal Dominant Charcot-Marie-Tooth Axonal Neuropathy Mapped on Chromosome 7p (CMT2D). Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996, 5, 1373–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züchner, S.; De Jonghe, P.; Jordanova, A.; Claeys, K.G.; Guergueltcheva, V.; Cherninkova, S.; Hamilton, S.R.; Van Stavern, G.; Krajewski, K.M.; Stajich, J.; et al. Axonal Neuropathy with Optic Atrophy Is Caused by Mutations in Mitofusin 2. Ann. Neurol. 2006, 59, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Episkopou, V.; Maeda, S.; Nishiguchi, S.; Shimada, K.; Gaitanaris, G.A.; Gottesman, M.E.; Robertson, E.J. Disruption of the Transthyretin Gene Results in Mice with Depressed Levels of Plasma Retinol and Thyroid Hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 2375–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liz, M.A.; Coelho, T.; Bellotti, V.; Fernandez-Arias, M.I.; Mallaina, P.; Obici, L. A Narrative Review of the Role of Transthyretin in Health and Disease. Neurol. Ther. 2020, 9, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, C.E.; Mar, F.M.; Franquinho, F.; Saraiva, M.J.; Sousa, M.M. Transthyretin Internalization by Sensory Neurons Is Megalin Mediated and Necessary for Its Neuritogenic Activity. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 3220–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, J.C.; Grandela, C.; Fernández-Ruiz, J.; de Miguel, R.; de Sousa, L.; Magalhães, A.I.; Saraiva, M.J.; Sousa, N.; Palha, J.A. Transthyretin Is Involved in Depression-like Behaviour and Exploratory Activity. J. Neurochem. 2004, 88, 1052–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.D.; Lambertsen, K.L.; Clausen, B.H.; Akinc, A.; Alvarez, R.; Finsen, B.; Saraiva, M.J. CSF Transthyretin Neuroprotection in a Mouse Model of Brain Ischemia. J. Neurochem. 2010, 115, 1434–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.C.; Marques, F.; Dias-Ferreira, E.; Cerqueira, J.J.; Sousa, N.; Palha, J.A. Transthyretin Influences Spatial Reference Memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2007, 88, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouillette, J.; Quirion, R. Transthyretin: A Key Gene Involved in the Maintenance of Memory Capacities during Aging. Neurobiol. Aging 2008, 29, 1721–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Pu, S.; Yin, J.; Gao, Q. Serum Prealbumin (Transthyretin) Predict Good Outcome in Young Patients with Cerebral Infarction. Clin. Exp. Med. 2011, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzman, A.L.; Gregori, L.; Vitek, M.P.; Lyubski, S.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Enghilde, J.J.; Bhasin, R.; Silverman, J.; Weisgraber, K.H.; Coyle, P.K. Transthyretin Sequesters Amyloid Beta Protein and Prevents Amyloid Formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 8368–8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloeckner, S.F.; Meyne, F.; Wagner, F.; Heinemann, U.; Krasnianski, A.; Meissner, B.; Zerr, I. Quantitative Analysis of Transthyretin, Tau and Amyloid-Beta in Patients with Dementia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2008, 14, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riisøen, H. Reduced Prealbumin (Transthyretin) in CSF of Severely Demented Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1988, 78, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S.M.; Cardoso, I.; Saraiva, M.J. Transthyretin: Roles in the Nervous System beyond Thyroxine and Retinol Transport. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 7, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luigetti, M.; Conte, A.; Del Grande, A.; Bisogni, G.; Madia, F.; Lo Monaco, M.; Laurenti, L.; Obici, L.; Merlini, G.; Sabatelli, M. TTR-Related Amyloid Neuropathy: Clinical, Electrophysiological and Pathological Findings in 15 Unrelated Patients. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 34, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemer, J.M.; Grote-Levi, L.; Hänselmann, A.; Sassmann, M.L.; Nay, S.; Ratuszny, D.; Körner, S.; Seeliger, T.; Hümmert, M.W.; Dohrn, M.F.; et al. Polyneuropathy in Hereditary and Wildtype Transthyretin Amyloidosis, Comparison of Key Clinical Features and Red Flags. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattianayagam, P.T.; Hahn, A.F.; Whelan, C.J.; Gibbs, S.D.J.; Pinney, J.H.; Stangou, A.J.; Rowczenio, D.; Pflugfelder, P.W.; Fox, Z.; Lachmann, H.J.; et al. Cardiac Phenotype and Clinical Outcome of Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy Associated with Transthyretin Alanine 60 Variant. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planté-Bordeneuve, V.; Ferreira, A.; Lalu, T.; Zaros, C.; Lacroix, C.; Adams, D.; Said, G. Diagnostic Pitfalls in Sporadic Transthyretin Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy (TTR-FAP). Neurology 2007, 69, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekijima, Y.; Dendle, M.A.; Kelly, J.W. Orally Administered Diflunisal Stabilizes Transthyretin against Dissociation Required for Amyloidogenesis. Amyloid 2006, 13, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razin, S.V.; Borunova, V.V.; Maksimenko, O.G.; Kantidze, O.L. Cys2His2 Zinc Finger Protein Family: Classification, Functions, and Major Members. Biochem. Biokhimiia 2012, 77, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, M.; Greenberg, M.E. The Regulation and Function of C-Fos and Other Immediate Early Genes in the Nervous System. Neuron 1990, 4, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangnekar, V.M.; Aplin, A.C.; Sukhatme, V.P. The Serum and TPA Responsive Promoter and Intron-Exon Structure of EGR2, a Human Early Growth Response Gene Encoding a Zinc Finger Protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990, 18, 2749–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, K.J.; Tourtellotte, W.G.; Millbrandt, J.; Baraban, J.M. The EGR Family of Transcription-Regulatory Factors: Progress at the Interface of Molecular and Systems Neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 1999, 22, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topilko, P.; Schneider-Maunoury, S.; Levi, G.; Baron-Van Evercooren, A.; Chennoufi, A.B.; Seitanidou, T.; Babinet, C.; Charnay, P. Krox-20 Controls Myelination in the Peripheral Nervous System. Nature 1994, 371, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, L.E.; Mancias, P.; Butler, I.J.; McDonald, C.M.; Keppen, L.; Koob, K.G.; Lupski, J.R. Mutations in the Early Growth Response 2 (EGR2) Gene Are Associated with Hereditary Myelinopathies. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, R.; Svaren, J.; Le, N.; Araki, T.; Watson, M.; Milbrandt, J. EGR2 Mutations in Inherited Neuropathies Dominant-Negatively Inhibit Myelin Gene Expression. Neuron 2001, 30, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, S.E.; Ward, R.M.; Svaren, J. Neuropathy-Associated Egr2 Mutants Disrupt Cooperative Activation of Myelin Protein Zero by Egr2 and Sox10. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 3521–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüst, H.M.; Wegener, A.; Fröb, F.; Hartwig, A.C.; Wegwitz, F.; Kari, V.; Schimmel, M.; Tamm, E.R.; Johnsen, S.A.; Wegner, M.; et al. Egr2-Guided Histone H2B Monoubiquitination Is Required for Peripheral Nervous System Myelination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 8959–8976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellone, E.; Di Maria, E.; Soriani, S.; Varese, A.; Doria, L.L.; Ajmar, F.; Mandich, P. A Novel Mutation (D305V) in the Early Growth Response 2 Gene Is Associated with Severe Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 1 Disease. Hum. Mutat. 1999, 14, 353–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numakura, C.; Shirahata, E.; Yamashita, S.; Kanai, M.; Kijima, K.; Matsuki, T.; Hayasaka, K. Screening of the Early Growth Response 2 Gene in Japanese Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1. J. Neurol. Sci. 2003, 210, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Dawson, D.B.; Thorland, E.C.; Lundquist, P.A.; Eckloff, B.W.; Wu, Y.; Baheti, S.; Evans, J.M.; Scherer, S.S.; et al. Target-Enrichment Sequencing and Copy Number Evaluation in Inherited Polyneuropathy. Neurology 2016, 86, 1762–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, C.; Spagnoli, C.; Salerno, G.G.; Pavlidis, E.; Frattini, D.; Pisani, F.; Bassi, M.T. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease with Pyramidal Features Due to a New Mutation of EGR2 Gene. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2019, 90, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikesová, E.; Hühne, K.; Rautenstrauss, B.; Mazanec, R.; Baránková, L.; Vyhnálek, M.; Horácek, O.; Seeman, P. Novel EGR2 Mutation R359Q Is Associated with CMT Type 1 and Progressive Scoliosis. Neuromuscul. Disord. NMD 2005, 15, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiga, K.; Noto, Y.; Mizuta, I.; Hashiguchi, A.; Takashima, H.; Nakagawa, M. A Novel EGR2 Mutation within a Family with a Mild Demyelinating Form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. JPNS 2012, 17, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozza, S.; Magri, S.; Pennisi, E.M.; Schirinzi, E.; Pisciotta, C.; Balistreri, F.; Severi, D.; Ricci, G.; Siciliano, G.; Taroni, F.; et al. A Novel Family with Axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Caused by a Mutation in the EGR2 Gene. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. JPNS 2019, 24, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareyson, D.; Taroni, F.; Botti, S.; Morbin, M.; Baratta, S.; Lauria, G.; Ciano, C.; Sghirlanzoni, A. Cranial Nerve Involvement in CMT Disease Type 1 Due to Early Growth Response 2 Gene Mutation. Neurology 2000, 54, 1696–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briani, C.; Taioli, F.; Lucchetta, M.; Bombardi, R.; Fabrizi, G. Adult Onset Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1D with an Arg381Cys Mutation of EGR2. Muscle Nerve 2010, 41, 888–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Hashiguchi, A.; Suzuki, S.; Uozumi, K.; Tokunaga, S.; Takashima, H. Vincristine Exacerbates Asymptomatic Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease with a Novel EGR2 Mutation. Neurogenetics 2012, 13, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosz, B.R.; Golovchenko, N.B.; Ellis, M.; Kumar, K.; Nicholson, G.A.; Antonellis, A.; Kennerson, M.L. A de novo EGR2 variant, c.1232A > G p.Asp411Gly, causes severe early-onset Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy Type 3 (Dejerine-Sottas Neuropathy). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, V.; De Jonghe, P.; Ceuterick, C.; De Vriendt, E.; Löfgren, A.; Nelis, E.; Warner, L.E.; Lupski, J.R.; Martin, J.-J.; Van Broeckhoven, C. Novel Missense Mutation in the Early Growth Response 2 Gene Associated with Dejerine–Sottas Syndrome Phenotype. Neurology 1999, 52, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, C.S.; Sherman, D.L.; Fleetwood-Walker, S.M.; Cottrell, D.F.; Tait, S.; Garry, E.M.; Wallace, V.C.; Ure, J.; Griffiths, I.R.; Smith, A.; et al. Peripheral Demyelination and Neuropathic Pain Behavior in Periaxin-Deficient Mice. Neuron 2000, 26, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; O’Brien, R.J.; Fung, E.T.; Lanahan, A.A.; Worley, P.F.; Huganir, R.L. GRIP: A Synaptic PDZ Domain-Containing Protein That Interacts with AMPA Receptors. Nature 1997, 386, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, G.; Chao, M. Axons Regulate Schwann Cell Expression of the Major Myelin and NGF Receptor Genes. Dev. Camb. Engl. 1988, 102, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raasakka, A.; Linxweiler, H.; Brophy, P.J.; Sherman, D.L.; Kursula, P. Direct Binding of the Flexible C-terminal Segment of Periaxin to Β4 Integrin Suggests a Molecular Basis for CMT4F. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Hyun, Y.S.; Nam, S.H.; Koo, H.; Hong, Y.B.; Chung, K.W.; Choi, B.-O. Novel Compound Heterozygous Nonsense PRX Mutations in a Korean Dejerine-Sottas Neuropathy Family. J. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 11, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, C.; Milani, M.; Morbin, M.; Cesani, M.; Lauria, G.; Scaioli, V.; Piccolo, G.; Fabrizi, G.M.; Cavallaro, T.; Taroni, F.; et al. Four Novel Cases of Periaxin-Related Neuropathy and Review of the Literature. Neurology 2010, 75, 1830–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.S.; Chan, A.; Costelha, S.; Fishman, S.; Willoughby, J.L.S.; Borland, T.D.; Milstein, S.; Foster, D.J.; Gonçalves, P.; Chen, Q.; et al. Preclinical Evaluation of RNAi as a Treatment for Transthyretin-Mediated Amyloidosis. Amyloid Int. J. Exp. Clin. Investig. Off. J. Int. Soc. Amyloidosis 2016, 23, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otagiri, T.; Sugai, K.; Kijima, K.; Arai, H.; Sawaishi, Y.; Shimohata, M.; Hayasaka, K. Periaxin Mutation in Japanese Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 51, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerkoel, C.F.; Takashima, H.; Stankiewicz, P.; Garcia, C.A.; Leber, S.M.; Rhee-Morris, L.; Lupski, J.R. Periaxin Mutations Cause Recessive Dejerine-Sottas Neuropathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 68, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijima, K.; Numakura, C.; Shirahata, E.; Sawaishi, Y.; Shimohata, M.; Igarashi, S.; Tanaka, T.; Hayasaka, K. Periaxin Mutation Causes Early-Onset but Slow-Progressive Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 49, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbot, A. A Mutation in Periaxin Is Responsible for CMT4F, an Autosomal Recessive Form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, H.; Boerkoel, C.F.; De Jonghe, P.; Ceuterick, C.; Martin, J.-J.; Voit, T.; Schröder, J.-M.; Williams, A.; Brophy, P.J.; Timmerman, V.; et al. Periaxin Mutations Cause a Broad Spectrum of Demyelinating Neuropathies. Ann. Neurol. 2002, 51, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nualart-Marti, A.; del Molino, E.M.; Grandes, X.; Bahima, L.; Martin-Satué, M.; Puchal, R.; Fasciani, I.; González-Nieto, D.; Ziganshin, B.; Llobet, A.; et al. Role of Connexin 32 Hemichannels in the Release of ATP from Peripheral Nerves. Glia 2013, 61, 1976–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procacci, P.; Magnaghi, V.; Pannese, E. Perineuronal Satellite Cells in Mouse Spinal Ganglia Express the Gap Junction Protein Connexin43 throughout Life with Decline in Old Age. Brain Res. Bull. 2008, 75, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, C.; Dermietzel, R.; Davidson, K.G.V.; Yasumura, T.; Rash, J.E. Connexin32-Containing Gap Junctions in Schwann Cells at the Internodal Zone of Partial Myelin Compaction and in Schmidt–Lanterman Incisures. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 3186–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, R.D.; Ni, Y. Nonsynaptic Communication through ATP Release from Volume-Activated Anion Channels in Axons. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3, ra73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, R. Connexins Control Glial Inflammation in Various Neurological Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondurand, N.; Girard, M.; Pingault, V.; Lemort, N.; Dubourg, O.; Goossens, M. Human Connexin 32, a Gap Junction Protein Altered in the X-Linked Form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease, Is Directly Regulated by the Transcription Factor SOX10. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 2783–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionasescu, V.; Searby, C.; Ionasescu, R. Point Mutations of the Connexin32 (GJB1) Gene in X-Linked Dominant Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994, 3, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, R.; White, T.W.; Scherer, S.S.; Fischbeck, K.H.; Paul, D.L. Null Mutations of Connexin32 in Patients with X-Linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Neuron 1994, 13, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, L.J.; Dahl, N.; Lensch, M.W.; Chance, P.F.; Kelly, T.; Le Guern, E.; Magi, S.; Parry, G.; Shapiro, H.; Wang, S. New Connexin32 Mutations Associated with X-Linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Neurology 1995, 45, 1863–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ressot, C.; Gomès, D.; Dautigny, A.; Pham-Dinh, D.; Bruzzone, R. Connexin32 Mutations Associated with X-Linked Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease Show Two Distinct Behaviors: Loss of Function and Altered Gating Properties. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 4063–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, D.; Patzkó, Á.; Schreiber, D.; van Hauwermeiren, A.; Baier, M.; Groh, J.; West, B.L.; Martini, R. Targeting the Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor Alleviates Two Forms of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease in Mice. Brain J. Neurol. 2015, 138, 3193–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, A.S.; Kulkarni, A.A.; Kanwar, R.; Klein, C.J.; Therneau, T.M.; Qin, R.; Banck, M.S.; Boora, G.K.; Ruddy, K.J.; Wu, Y.; et al. Sequencing of Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease Genes in a Toxic Polyneuropathy. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 76, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Takita, J.; Tanaka, Y.; Setou, M.; Nakagawa, T.; Takeda, S.; Yang, H.W.; Terada, S.; Nakata, T.; Takei, Y.; et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 2A Caused by Mutation in a Microtubule Motor KIF1Bbeta. Cell 2001, 105, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, K.; De Jonghe, P.; Coen, K.; Verpoorten, N.; Auer-Grumbach, M.; Kwon, J.M.; FitzPatrick, D.; Schmedding, E.; De Vriendt, E.; Jacobs, A.; et al. Mutations in the Small GTP-Ase Late Endosomal Protein RAB7 Cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 2B Neuropathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 72, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonellis, A.; Ellsworth, R.E.; Sambuughin, N.; Puls, I.; Abel, A.; Lee-Lin, S.-Q.; Jordanova, A.; Kremensky, I.; Christodoulou, K.; Middleton, L.T.; et al. Glycyl tRNA Synthetase Mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 2D and Distal Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type V. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 72, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, R.V.; Ben Othmane, K.; Rochelle, J.M.; Stajich, J.E.; Hulette, C.; Dew-Knight, S.; Hentati, F.; Ben Hamida, M.; Bel, S.; Stenger, J.E.; et al. Ganglioside-Induced Differentiation-Associated Protein-1 Is Mutant in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 4A/8q21. Nat. Genet. 2002, 30, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojkovic, T.; Latour, P.; Viet, G.; de Seze, J.; Hurtevent, J.-F.; Vandenberghe, A.; Vermersch, P. Vocal Cord and Diaphragm Paralysis, as Clinical Features of a French Family with Autosomal Recessive Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease, Associated with a New Mutation in the GDAP1 Gene. Neuromuscul. Disord. NMD 2004, 14, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmar, B.; Innes, A.; Wanisch, K.; Kolaszynska, A.K.; Pandraud, A.; Kelly, G.; Abramov, A.Y.; Reilly, M.M.; Schiavo, G.; Greensmith, L. Mitochondrial Deficits and Abnormal Mitochondrial Retrograde Axonal Transport Play a Role in the Pathogenesis of Mutant Hsp27-Induced Charcot Marie Tooth Disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 3313–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irobi, J.; Van Impe, K.; Seeman, P.; Jordanova, A.; Dierick, I.; Verpoorten, N.; Michalik, A.; De Vriendt, E.; Jacobs, A.; Van Gerwen, V.; et al. Hot-Spot Residue in Small Heat-Shock Protein 22 Causes Distal Motor Neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganea, E. Chaperone-like Activity of Alpha-Crystallin and Other Small Heat Shock Proteins. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2001, 2, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padua, L.; LoMonaco, M.; Gregori, B.; Valente, E.M.; Padua, R.; Tonali, P. Neurophysiological Classification and Sensitivity in 500 Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Hands. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1997, 96, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniou, P.; Fontes, M. Therapeutic Development in Charcot Marie Tooth Type 1 Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Qin, B.; Zhang, H.; Lei, L.; Wu, S. Current Treatment Methods for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutary, S.; Echaniz-Laguna, A.; Adams, D.; Loisel-Duwattez, J.; Schumacher, M.; Massaad, C.; Massaad-Massade, L. Treating PMP22 Gene Duplication-Related Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: The Past, the Present and the Future. Transl. Res. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2021, 227, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonelli, E.; Ballabio, M.; Consoli, A.; Roglio, I.; Magnaghi, V.; Melcangi, R.C. Neuroactive Steroids: A Therapeutic Approach to Maintain Peripheral Nerve Integrity during Neurodegenerative Events. J. Mol. Neurosci. MN 2006, 28, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskelä, T.T.; Markkanen, P.M.H.; Pietilä, E.M.; Tuusa, J.T.; Petäjä-Repo, U.E. Opioid Receptor Pharmacological Chaperones Act by Binding and Stabilizing Newly Synthesized Receptors in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 23171–23183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R. Role of Naturally Occurring Osmolytes in Protein Folding and Stability. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2009, 491, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prukop, T.; Stenzel, J.; Wernick, S.; Kungl, T.; Mroczek, M.; Adam, J.; Ewers, D.; Nabirotchkin, S.; Nave, K.-A.; Hajj, R.; et al. Early Short-Term PXT3003 Combinational Therapy Delays Disease Onset in a Transgenic Rat Model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease 1A (CMT1A). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attarian, S.; Young, P.; Brannagan, T.H.; Adams, D.; Van Damme, P.; Thomas, F.P.; Casanovas, C.; Kafaie, J.; Tard, C.; Walter, M.C.; et al. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trial of PXT3003 for the Treatment of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 1A. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Grado, A.; Serio, M.; Saveri, P.; Pisciotta, C.; Pareyson, D. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Review of Clinical Developments and Its Management—What’s New in 2025? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2025, 25, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morena, J.; Gupta, A.; Hoyle, J.C. Charcot-Marie-Tooth: From Molecules to Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, M.; Kleopa, K.A. CMT1A Current Gene Therapy Approaches and Promising Biomarkers. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, B.; Hajjar, H.; Soares, S.; Berthelot, J.; Deck, M.; Abbou, S.; Campbell, G.; Ceprian, M.; Gonzalez, S.; Fovet, C.-M.; et al. AAV2/9-Mediated Silencing of PMP22 Prevents the Development of Pathological Features in a Rat Model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease 1 A. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, M.; Kagiava, A.; Choudury, S.G.; Jennings, M.J.; Wallace, L.M.; Fowler, A.M.; Heslegrave, A.; Richter, J.; Tryfonos, C.; Christodoulou, C.; et al. A Translatable RNAi-Driven Gene Therapy Silences PMP22/Pmp22 Genes and Improves Neuropathy in CMT1A Mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e159814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, M.; Kagiava, A.; Sargiannidou, I.; Georgiou, E.; Kleopa, K.A. Charcot–Marie–Tooth Neuropathies: Current Gene Therapy Advances and the Route toward Translation. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2023, 28, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, M.S.; Ranum, P.T.; Yrigollen, C.M.; Carrell, E.M.; Smith, G.R.; Muehlmatt, A.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Stein, J.M.; Wolf, R.L.; Radaelli, E.; et al. Toxicity after AAV Delivery of RNAi Expression Constructs into Nonhuman Primate Brain. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Lee, J.Y.; Song, D.W.; Bae, H.S.; Doo, H.M.; Yu, H.S.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, H.K.; Hwang, H.; Kwak, G.; et al. Targeted PMP22 TATA-Box Editing by CRISPR/Cas9 Reduces Demyelinating Neuropathy of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1A in Mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yen, C.-W.; Lin, H.-C.; Hou, W.; Estevez, A.; Sarode, A.; Goyon, A.; Bian, J.; Lin, J.; Koenig, S.G.; et al. Automated High-Throughput Preparation and Characterization of Oligonucleotide-Loaded Lipid Nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 599, 120392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.T.; Damle, S.; Ikeda-Lee, K.; Kuntz, S.; Li, J.; Mohan, A.; Kim, A.; Hung, G.; Scheideler, M.A.; Scherer, S.S.; et al. PMP22 Antisense Oligonucleotides Reverse Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1A Features in Rodent Models. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shy, M.E. Antisense Oligonucleotides Offer Hope to Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1A. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rüger, J.; Ioannou, S.; Castanotto, D.; Stein, C.A. Oligonucleotides to the (Gene) Rescue: FDA Approvals 2017–2019. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, M.C.P.; Kont, A.; Aburto, M.R.; Cryan, J.F.; O’Driscoll, C.M. Advances in the Design of (Nano)Formulations for Delivery of Antisense Oligonucleotides and Small Interfering RNA: Focus on the Central Nervous System. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 1491–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato-Yamada, Y.; Strickland, A.; Sasaki, Y.; Bloom, J.; DiAntonio, A.; Milbrandt, J. A SARM1-Mitochondrial Feedback Loop Drives Neuropathogenesis in a Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 2A Rat Model. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, C.; Rizzo, F.; Anastasia, A.; Comi, G.; Corti, S.; Abati, E. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 2A: An Update on Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Perspectives. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 193, 106467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Sakai, K.; Nakamura, T.; Matsumoto, K. Hepatocyte Growth Factor Twenty Years on: Much More than a Growth Factor. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 26, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, J.A.; Shaibani, A.; Sang, C.N.; Christiansen, M.; Kudrow, D.; Vinik, A.; Shin, N.; VM202 study group. Gene Therapy for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Study of VM202, a Plasmid DNA Encoding Human Hepatocyte Growth Factor. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Ko, K.R.; Kim, S. Hepatocyte Growth Factor Regulates the miR-206-HDAC4 Cascade to Control Neurogenic Muscle Atrophy Following Surgical Denervation in Mice. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 12, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Kim, H.S.; Chi, S.A.; Nam, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.B.; Choi, B.-O. A Phase 1/2a, Open Label Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of a Plasmid DNA Encoding Human Hepatocyte Growth Factor in Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease 1A; Research Square: Durham, NC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahenk, Z.; Ozes, B. Gene Therapy to Promote Regeneration in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Brain Res. 2020, 1727, 146533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozes, B.; Myers, M.; Moss, K.; Mckinney, J.; Ridgley, A.; Chen, L.; Bai, S.; Abrams, C.K.; Freidin, M.M.; Mendell, J.R.; et al. AAV1.NT-3 Gene Therapy for X-Linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy Type 1. Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozes, B.; Tong, L.; Moss, K.; Myers, M.; Morrison, L.; Attia, Z.; Sahenk, Z. AAV1.tMCK.NT-3 Gene Therapy Improves Phenotype in Sh3tc2−/− Mouse Model of Charcot–Marie–Tooth Type 4C. Brain Commun. 2024, 6, fcae394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel-Campos, D.; Sleigh, J.N. Targeting Muscle to Treat Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozes, B.; Moss, K.; Myers, M.; Ridgley, A.; Chen, L.; Murrey, D.; Sahenk, Z. AAV1.NT-3 Gene Therapy in a CMT2D Model: Phenotypic Improvements in GarsP278KY/+ Mice. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-D.; Wu, C.-L.; Hwang, W.-C.; Yang, D.-I. More Insight into BDNF against Neurodegeneration: Anti-Apoptosis, Anti-Oxidation, and Suppression of Autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luigetti, M.; Romano, A.; Di Paolantonio, A.; Bisogni, G.; Sabatelli, M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR) Polyneuropathy: Current Perspectives on Improving Patient Care. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2020, 16, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, M.S.; Kale, P.; Fontana, M.; Berk, J.L.; Grogan, M.; Gustafsson, F.; Hung, R.R.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Damy, T.; González-Duarte, A.; et al. Patisiran Treatment in Patients with Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urits, I.; Swanson, D.; Swett, M.C.; Patel, A.; Berardino, K.; Amgalan, A.; Berger, A.A.; Kassem, H.; Kaye, A.D.; Viswanath, O. A Review of Patisiran (ONPATTRO®) for the Treatment of Polyneuropathy in People with Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Neurol. Ther. 2020, 9, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.; Algalarrondo, V.; Echaniz-Laguna, A. Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis in the Era of RNA Interference, Antisense Oligonucleotide, and CRISPR-Cas9 Treatments. Blood 2023, 142, 1600–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillmore, J.D.; Gane, E.; Taubel, J.; Kao, J.; Fontana, M.; Maitland, M.L.; Seitzer, J.; O’Connell, D.; Walsh, K.R.; Wood, K.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 In Vivo Gene Editing for Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, T. Eplontersen: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteles, R.M.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Morbach, C.; Gillmore, J.D.; Taylor, M.S.; Conceição, I.; White, W.B.; Kwok, C.; Sweetser, M.T.; Boyle, K.L.; et al. Vutrisiran in Transthyretin Amyloidosis. JACC Adv. 2025, 4, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, M.; Qureshi, T.; Torella, A.; Laine, P.; Giugliano, T.; Jonson, P.H.; Johari, M.; Paulin, L.; Piluso, G.; Auvinen, P.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Splicing Defects by Single-Molecule Real-Time Sequencing Technology (PacBio). J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2020, 7, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.; Gessler, D.J.; Zhan, W.; Gallagher, T.L.; Gao, G. Adeno-Associated Virus as a Delivery Vector for Gene Therapy of Human Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lent, J.; Prior, R.; Pérez Siles, G.; Cutrupi, A.N.; Kennerson, M.L.; Vangansewinkel, T.; Wolfs, E.; Mukherjee-Clavin, B.; Nevin, Z.; Judge, L.; et al. Advances and Challenges in Modeling Inherited Peripheral Neuropathies Using iPSCs. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1348–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genetic Alterations | Pathophysiology Mechanism | Disease | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duplication of 17p11.2–p12 | Boost for P2RX7 expression → increase in calcium levels in mature Schwann cells → segmental demyelination | CMT1, RLS | [6,12,13,14] |

| Asp37Val substitution in the first extracellular domain | Overexpression of PMP22 → dysregulation of myelin proteins expression → suppression of the enzymes that catalyse cholesterol production → myelin thickness and shorter internodes | CMT1A | [15,16,17] |

| C > T substitution at c.402 (exon 4) | - | CMT1 | [18] |

| G > A substitution at c.178 | - | CMT1 | [19] |

| Deletion of exon 4 | - | CMT1 | [19] |

| p. His12Pro variation | - | CMT1 | [19] |

| p. Thr118Me | - | CMT1A in homozygosity; HNPP in heterozygosity | [18] |

| G > A substitution at c.202 (exon 3) | Decreased amount of PMP22 → insufficient for myelin formation → axons vulnerable to mechanical damage | HNPP | [11,20,21] |

| Deletion of 17p11.2–p12 | - | HNPP | [11,19] |

| Ser to Leu substitution | Supernumerary of Schwann cells, causing onion bulb formation and thickening of the myelin sheath | DSS | [22,23] |

| C > A substitution at c.85 | - | DSS | [24] |

| Met69Lys | - | DSS | [25,26] |

| Leu16Pro | - | DSS | [25,27] |

| Leu70Arg | - | DSS | [25,27] |

| Ser72Leu | - | DSS | [27] |

| T > C substitution at c.374 (exon 3) | - | CHN | [28,29] |

| Genetic Alterations | Pathophysiology Mechanism | Disease | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| C > T substitution at c.277 (exon 2) | ER retention, activation of the UPR, mis-glycosylation and disruption of myelin compaction, mistrafficking of mutant MPZ to the myelin sheath | CMT1B | [62,63] |

| G > A substitution at c.444 (exon 3) | - | CMT1B | [30] |

| replacement of Tyr181by a termination codon | - | CMT1B | [30] |

| replacement of Tyr154 by a termination codon | - | CMT1B | [30] |

| Arg98Cys | - | CMT1B | [64] |

| Ser63 deletion | - | CMT1B | [64] |

| Lys130Arg | - | DSS | [25,65] |

| Thr34Ile | - | DSS | [25,65] |

| Ser54Cys | - | DSS | [25,65] |

| Ile135Leu | - | DSS | [25,65] |

| Arg138Cys | - | DSS | [25,65] |

| Ile32Phe | - | DSS | [25,65] |

| Cys63Ser | - | DSS | [66] |

| Arg168Glyc | - | DSS | [66] |

| Arg69Cys | - | DSS | [46] |

| Ile1Met | - | DSS | [58] |

| Ile33Phe | - | DSS | [58] |

| Ser34Cys | - | DSS | [58] |

| Tyr53Cys | - | DSS | [58] |

| Lys101Arg | - | DSS | [58] |

| Ile106Thr | - | DSS | [58] |

| Deletion of Phe64 | - | DSS in homozygosity; CMT in heterozygosity | [67] |

| Frameshift mutations resulting in amino acid change after Leu-145 in the transmembrane domain | Defective myelin compaction | DSS | [46,68] |

| Frameshift mutation that causes amino acid change after Gly-74 in the extracellular domain | - | DSS | [46,68] |

| Replacement of Gln-186 by termination codon | Escape of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay → truncated proteins that act in a dominant-negative way, interfering with normal MPZ function | CHN | [63,69] |

| C > A substitution at c.727 (exon 3) | Affected myelin structure | RLS | [49,51] |

| C > T substitution at c.428 | - | RLS | [68,70] |

| Asn102Lys | - | RLS | [58] |

| Disease | Phenotype | Lesions | Genes | Mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMT1A | Symmetrical progressive muscle weakness and atrophy, limb deformities, loss of sensation, diminished/ absent tendon reflexes | Slow NCVs, axonal loss | PMP22 (overexpression) | Dysregulation of myelin proteins → lack of cholesterol → lower myelin thickness and shorter internodes Increase in calcium levels by P2RX7 → segmental demyelination | [13,14,16,17,18,19,20,24] |

| HNPP | Asymptomatic, gradual muscle weakness, located sensory loss, limping and refusal to walk, recurrent and self-limited nerve paralysis | Distinctive localized thickening of the myelin sheaths (tomacula), variable axonal loss, slow NCVs | PMP22 (loss of function) | Decreased PMP22 → increased permeability of myelin sheath → peripheral nerves susceptible to pressure induced injuries | [11,34,35,37,38,39] |

| DSS/CHN | Similar to CMT1A, but earlier appearance, hypesthesia, hypotonia, areflexia and thoracolumbar kyphoscoliosis, mild ptosis and limitations of eye movements, distal muscle weakness, joint contractures in the severe form, greater morbidity | Hypomyelination and basal laminae onion bulbs, slow NCVs | PMP22 | Supernumerary of Schwann cells → myelin formation deficiency → onion bulb formation and thickening of myelin sheath, demyelination, remyelination | [22,23,26,29,43,44,45] |

| MPZ | Defective myelin compaction, accumulation of misfolded MPZ in ER → Schwann cells stress | [63,68,69] | |||

| EGR2 | Reduced transcriptional activation of myelin-related genes, failure of Schwann cells full differentiation → defective myelination | [119,125] | |||

| PRX | Enzymatic defects, unstable cytoskeleton and myelin of Schwann cells → inability of rapid conduction of nerve signaling | [143,144] | |||

| RLS | Tremor, ataxia, muscular atrophy, bilateral pes cavus, loss of vibratory and position sense in upper and lower limbs, wide-based and ataxic gait and areflexia, mild scoliosis of the lower thoracic spine, high life expectancy | Hypertrophic and demyelinating lesions, slow NCVs, onion bulbs | PMP22 | Reduction of nerve conduction demyelination, presence of onion bulbs, shared mechanisms to CMT1A | [47,49,51,52] |

| MPZ | Dysfunctional myelin in the ER | [58,70] | |||

| CMT1B | Muscular weakness, foot abnormalities, sensory loss and discomfort, absent tendon reflexes, pes cavus and decreased sensation in distal extremities, bilateral facial weakness and absence of vibratory sensation in both legs | Slow NCVs | MPZ (gain of function and rarely loss of function) | Mutant MPZ remains in the ER rather than being transported to the cell membrane, activation of the UPR, mis-glycosylation and disruption of myelin compaction, mistrafficking of mutant MPZ to the myelin sheath, all leading to demyelination | [62,68,74,75,76] |

| CMT2A | Muscle weakness, greater severity of disability than CMT1, difficulty in walking, due to deformities of the lower limbs, tendon areflexia, leg muscle cramps, pes cavus, distal paralysis, finger tremor | Slow NCVs, decreased amplitudes of evoked motor and sensory nerve responses, variable loss of myelinated fibers, small onion bulbs | MFN2 | Axonopathy by impairing energy production along the axon, mitochondrial fragmentation without depolarization or perinuclear aggregation and block of final fusion step, unfolded protein | [82,87,89,90,91,93,94] |

| hTTR | Lower limb paresthesia, cardiomyopathy, gastrointestinal symptoms, postural hypotension, bladder dysfunction, paresthesia, burning and extending pain in the feet, dysesthesias, and dysautonomia | Slow NCVs, prolonged distal motor latencies | TTR | Axonal damage, decrease in repair after damage | [109,111,112,167] |

| CMT4F | Delay in development, distal muscle atrophy, mild kyphoscoliosis | Onion bulbs formation | PRX | Absence of a large repeat-rich domain, excessive myelin production de-remyelination cycles | [140,144,145] |

| CMT1X | Muscle weakness, sensory loss and atrophy with greater severity in males than females | Not well defined | CX32 | Dysregulation of immune-responding genes, obstruction of gap junction formation → failure in maintenance of myelin integrity → axonal | [152,156] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chrysostomaki, M.; Chatzi, D.; Kyriakoudi, S.A.; Meditskou, S.; Manthou, M.E.; Gargani, S.; Theotokis, P.; Dermitzakis, I. Hereditary Polyneuropathies in the Era of Precision Medicine: Genetic Complexity and Emerging Strategies. Genes 2026, 17, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010056

Chrysostomaki M, Chatzi D, Kyriakoudi SA, Meditskou S, Manthou ME, Gargani S, Theotokis P, Dermitzakis I. Hereditary Polyneuropathies in the Era of Precision Medicine: Genetic Complexity and Emerging Strategies. Genes. 2026; 17(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleChrysostomaki, Maria, Despoina Chatzi, Stella Aikaterini Kyriakoudi, Soultana Meditskou, Maria Eleni Manthou, Sofia Gargani, Paschalis Theotokis, and Iasonas Dermitzakis. 2026. "Hereditary Polyneuropathies in the Era of Precision Medicine: Genetic Complexity and Emerging Strategies" Genes 17, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010056

APA StyleChrysostomaki, M., Chatzi, D., Kyriakoudi, S. A., Meditskou, S., Manthou, M. E., Gargani, S., Theotokis, P., & Dermitzakis, I. (2026). Hereditary Polyneuropathies in the Era of Precision Medicine: Genetic Complexity and Emerging Strategies. Genes, 17(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010056