Embryonic Thermal Manipulation Affects Neurodevelopment and Induces Heat Tolerance in Layers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eggs and Incubation Management

2.2. Hatchling Performance Evaluation

2.3. Heat Tolerance Test of Chicks

2.4. Morphological and Pathological Analysis of the Brains

2.5. Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis

2.6. RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

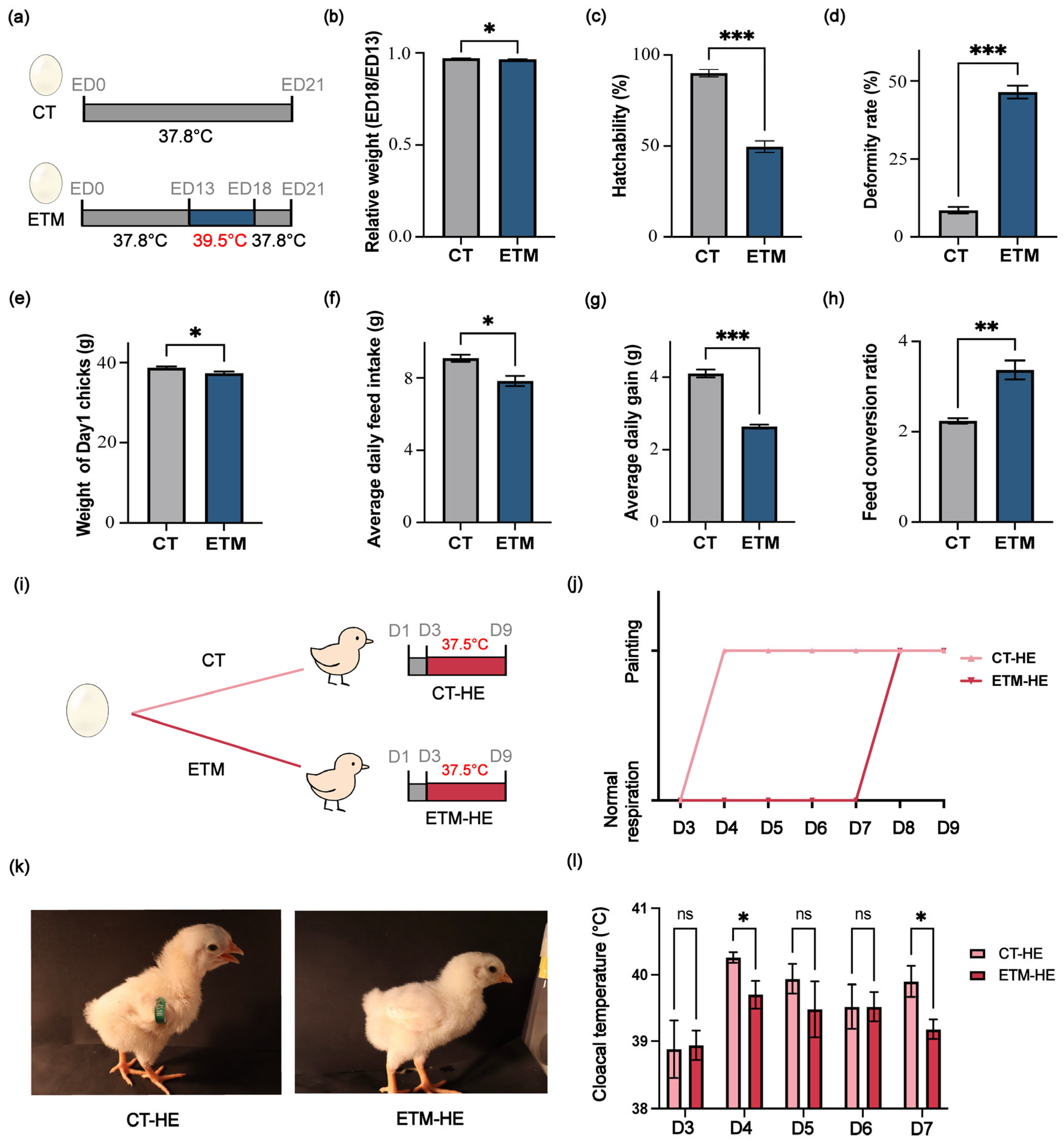

3.1. Embryonic Thermal Manipulation Affects Hatchling Performance and Heat Tolerance

3.2. Embryonic Thermal Manipulation Impedes Brain Development

3.3. Transcriptomic Profiling Uncovers Regulatory Networks in Brains Mediated by Embryonic Thermal Manipulation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yue, K.; Cao, Q.Q.; Shaukat, A.; Zhang, C.; Huang, S.C. Insights into the evaluation, influential factors and improvement strategies for poultry meat quality: A review. NPJ Sci. Food 2024, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Mollier, R.T.; Paton, R.N.; Pongener, N.; Yadav, R.; Singh, V.; Katiyar, R.; Kumar, R.; Sonia, C.; Bhatt, M.; et al. Backyard poultry farming with improved germplasm: Sustainable food production and nutritional security in fragile ecosystem. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 962268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffel, E.D.; Horton, R.M.; de Sherbinin, A. Temperature and humidity based projections of a rapid rise in global heat stress exposure during the 21st century. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 014001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.; Nelson, G.; Mayberry, D.; Herrero, M. Increases in extreme heat stress in domesticated livestock species during the twenty-first century. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 5762–5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugaletta, G.; Teyssier, J.R.; Rochell, S.J.; Dridi, S.; Sirri, F. A review of heat stress in chickens. Part I: Insights into physiology and gut health. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 934381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Ratwan, P.; Dahiya, S.P.; Nehra, A.K. Climate change and heat stress: Impact on production, reproduction and growth performance of poultry and its mitigation using genetic strategies. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 97, 102867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Yu, Y.H.; Hsiao, F.S.; Su, C.H.; Liu, H.C.; Tobin, I.; Zhang, G.; Cheng, Y.H. Influence of heat stress on poultry growth performance, intestinal inflammation, and immune function and potential mitigation by probiotics. Animals 2022, 12, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Ryu, C.; Lee, S.D.; Cho, J.H.; Kang, H. Effects of heat stress on the laying performance, egg quality, and physiological response of laying hens. Animals 2024, 14, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, A.; Mahmoud, M.; Murugesan, R.; Cheng, H.W. Effect of a synbiotic supplement on fear response and memory assessment of broiler chickens subjected to heat stress. Animals 2021, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, V.S. Heat stress biomarker amino acids and neuropeptide afford thermotolerance in chicks. J. Poult. Sci. 2019, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A. Heat stress management in poultry. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 2021, 105, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Sultan, M.; Bilal, M.; Ashraf, H.; Farooq, M.; Miyazaki, T.; Sajjad, U.; Ali, I.; Hussain, M.I. Experiments on energy-efficient evaporative cooling systems for poultry farm application in Multan (Pakistan). Sustainability 2021, 13, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onagbesan, O.M.; Uyanga, V.A.; Oso, O.; Tona, K.; Oke, O.E. Alleviating heat stress effects in poultry: Updates on methods and mechanisms of actions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1255520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, F.; Adewole, D. Environmental stress in chickens and the potential effectiveness of dietary vitamin supplementation. Front. Anim. Sci. 2021, 2, 775311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangan, M.; Siwek, M. Strategies to combat heat stress in poultry production: A review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 108, 576–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncho, C.M.; Goel, A.; Gupta, V.; Jeong, C.M.; Choi, Y.H. Impact of embryonic manipulations on core body temperature dynamics and survival in broilers exposed to cyclic heat stress. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zghoul, M.B. Thermal manipulation during broiler chicken embryogenesis increases basal mRNA levels and alters production dynamics of heat shock proteins 70 and 60 and heat shock factors 3 and 4 during thermal stress. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3661–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piestun, Y.; Shinder, D.; Ruzal, M.; Halevy, O.; Brake, J.; Yahav, S. Thermal manipulations during broiler embryogenesis: Effect on the acquisition of thermotolerance. Poult. Sci. 2008, 87, 1516–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Amaz, S.; Shahid, M.A.H.; Chaudhary, A.; Jha, R.; Mishra, B. Embryonic thermal manipulation reduces hatch time, increases hatchability, thermotolerance, and liver metabolism in broiler embryos. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohler, M.W.; Chowdhury, V.S.; Cline, M.A.; Gilbert, E.R. Heat stress responses in birds: A review of the neural components. Biology 2021, 10, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.F. Central neural control of thermoregulation and brown adipose tissue. Auton. Neurosci. 2016, 196, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Cai, H.; Han, Y.; Yang, P. Mechanisms of heat stress on neuroendocrine and organ damage and nutritional measures of prevention and treatment in poultry. Biology 2024, 13, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, K.X.; Deng, Z.C.; Li, S.J.; Yi, D.; He, X.; Yang, X.J.; Guo, Y.M.; Sun, L.H. Poultry nutrition: Achievement, challenge, and strategy. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 3554–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyssier, J.R.; Brugaletta, G.; Sirri, F.; Dridi, S.; Rochell, S.J. A review of heat stress in chickens. Part II: Insights into protein and energy utilization and feeding. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 943612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanga, V.A.; Musa, T.H.; Oke, O.E.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Jiao, H.; Onagbesan, O.M.; Lin, H. Global trends and research frontiers on heat stress in poultry from 2000 to 2021: A bibliometric analysis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1123582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, A.; Tolba, S.; Mahrose, K.; Felemban, S.G.; Khafaga, A.F.; Khalifa, N.E.; Jaremko, M.; Moustafa, M.; Alshaharni, M.O.; Algopish, U.; et al. Heat shock proteins as a key defense mechanism in poultry production under heat stress conditions. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Bao, E.; Tang, S. The protective role of heat shock proteins against stresses in animal breeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, S.L.; Hain, B.; Senf, S.M.; Judge, A.R. Hsp27 inhibits IKKβ-induced NF-κB activity and skeletal muscle atrophy. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 3415–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Ncho, C.M.; Choi, Y.H. Regulation of gene expression in chickens by heat stress. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liao, H.; Lin, Z.; Tang, Q. Insights into the role of glutathione peroxidase 3 in non-neoplastic diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glory, A.; Averill-Bates, D.A. The antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 contributes to the protective effect of mild thermotolerance (40 °C) against heat shock-induced apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 99, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varatharaj, A.; Galea, I. The blood–brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Sun, Z.; Hu, W. Roles of astrocytes in cerebral infarction and related therapeutic strategies. J. Zhejiang Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 47, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalakshmi, A.M.; Ray, B.; Tuladhar, S.; Hediyal, T.A.; Raj, P.; Rathipriya, A.G.; Qoronfleh, M.W.; Essa, M.M.; Chidambaram, S.B. Impact of Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Modulators on Dendritic Spines Structure and Functions in Brain. Cells 2021, 10, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; You, Y.; Xu, C.; Chen, Z. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced pneumonia via modification of inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and autophagy. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, S.; Özkan, S.; Shah, T. Incubation temperature and lighting: Effect on embryonic development, post-hatch growth, and adaptive response. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 899977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Hu, Z.; Li, Q.; Gu, S.; Lan, F.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Shao, L.; Yang, N.; et al. Temperature-induced embryonic diapause in chickens is mediated by PKC-NF-κB-IRF1 signaling. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noiva, R.M.; Menezes, A.C.; Peleteiro, M.C. Influence of temperature and humidity manipulation on chicken embryonic development. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zghoul, M.B.; Jaradat, Z.W.; Ababneh, M.M.; Okour, M.Z.; Saleh, K.M.M.; Alkofahi, A.; Alboom, M.H. Effects of embryonic thermal manipulation on the immune response to post-hatch Escherichia coli challenge in broiler chicken. Vet. World 2023, 16, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelnokova, M.I.; Suleimanov, F.I.; Chelnokov, A.A. Synergistic effect of variable temperature and red LED lighting during incubation on the growth and metabolism of chicken embryos and the quality of day-old egg-cross chickens. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2023, 49, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, K.; Sabban, J.; Cerutti, C.; Devailly, G.; Foissac, S.; Gourichon, D.; Hubert, A.; Hubert, J.N.; Leroux, S.; Zerjal, T.; et al. Molecular responses of chicken embryos to maternal heat stress through DNA methylation and gene expression: A pilot study. Environ. Epigenet. 2025, 11, dvaf009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redza-Dutordoir, M.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 2977–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Lu, Z.; Ma, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Gao, F. Chronic heat stress alters hypothalamus integrity, the serum indexes and attenuates expressions of hypothalamic appetite genes in broilers. J. Therm. Biol. 2019, 81, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukumaran, A.; Choi, K.; Dasgupta, B. Insight on transcriptional regulation of the energy sensing AMPK and biosynthetic mTOR pathway genes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piestun, Y.; Harel, M.; Barak, M.; Yahav, S.; Halevy, O. Thermal manipulations in late-term chick embryos have immediate and longer term effects on myoblast proliferation and skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amaz, S.; Mishra, B. Embryonic thermal manipulation: A potential strategy to mitigate heat stress in broiler chickens for sustainable poultry production. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, K.M.M.; Tarkhan, A.H.; Al-Zghoul, M.B. Embryonic thermal manipulation affects the antioxidant response to post-hatch thermal exposure in broiler chickens. Animals 2020, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narinç, D.; Erdoğan, S.; Tahtabiçen, E.; Aksoy, T. Effects of thermal manipulations during embryogenesis of broiler chickens on developmental stability, hatchability and chick quality. Animals 2016, 10, 1328–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemsen, H.; Kamers, B.; Dahlke, F.; Han, H.; Song, Z.; Ansari Pirsaraei, Z.; Tona, K.; Decuypere, E.; Everaert, N. High- and low-temperature manipulation during late incubation: Effects on embryonic development, the hatching process, and metabolism in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 2678–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyau, T.; Métayer-Coustard, S.; Berri, C.; Crochet, S.; Cailleau-Audouin, E.; Sannier, M.; Chartrin, P.; Praud, C.; Hennequet-Antier, C.; Rideau, N.; et al. Thermal manipulation during embryogenesis has long-term effects on muscle and liver metabolism in fast-growing chickens. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyau, T.; Berri, C.; Bedrani, L.; Métayer-Coustard, S.; Praud, C.; Duclos, M.J.; Tesseraud, S.; Rideau, N.; Everaert, N.; Yahav, S.; et al. Thermal manipulation of the embryo modifies the physiology and body composition of broiler chickens reared in floor pens without affecting breast meat processing quality. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 3674–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fan, Z.; Jie, Y.; Niu, B.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Shao, L.-W. Embryonic Thermal Manipulation Affects Neurodevelopment and Induces Heat Tolerance in Layers. Genes 2026, 17, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010035

Fan Z, Jie Y, Niu B, Wu X, Chen X, Li J, Shao L-W. Embryonic Thermal Manipulation Affects Neurodevelopment and Induces Heat Tolerance in Layers. Genes. 2026; 17(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Zixuan, Yuchen Jie, Bowen Niu, Xinyu Wu, Xingying Chen, Junying Li, and Li-Wa Shao. 2026. "Embryonic Thermal Manipulation Affects Neurodevelopment and Induces Heat Tolerance in Layers" Genes 17, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010035

APA StyleFan, Z., Jie, Y., Niu, B., Wu, X., Chen, X., Li, J., & Shao, L.-W. (2026). Embryonic Thermal Manipulation Affects Neurodevelopment and Induces Heat Tolerance in Layers. Genes, 17(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010035