Uncovering the Genetic Structure of the Sekler Population in Transylvania Through Genome-Wide Autosomal Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Groups and Genotype Analysis

2.2. Population Structure and Ancestry Analyses

2.3. DNA Segment Analyses

3. Results

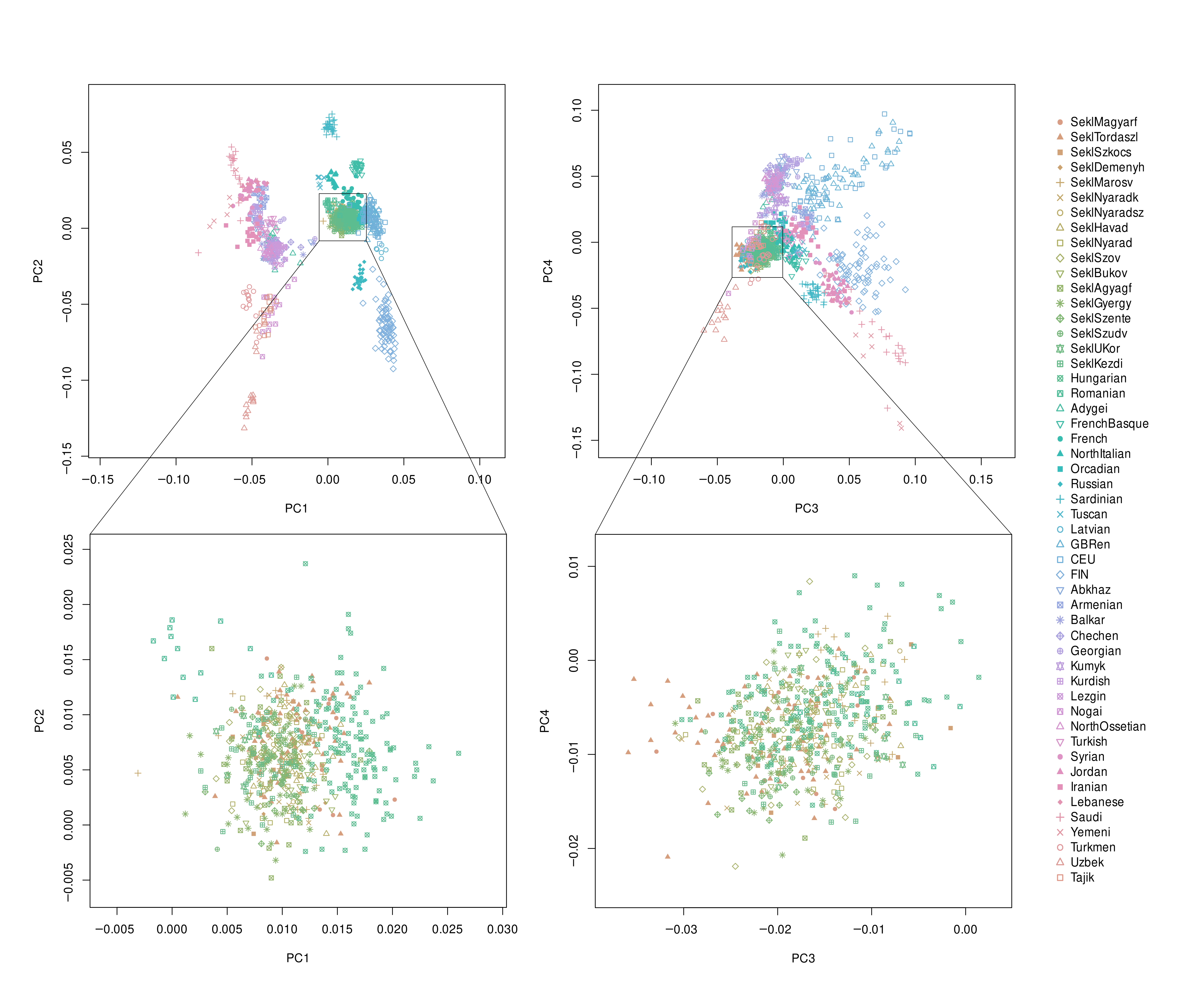

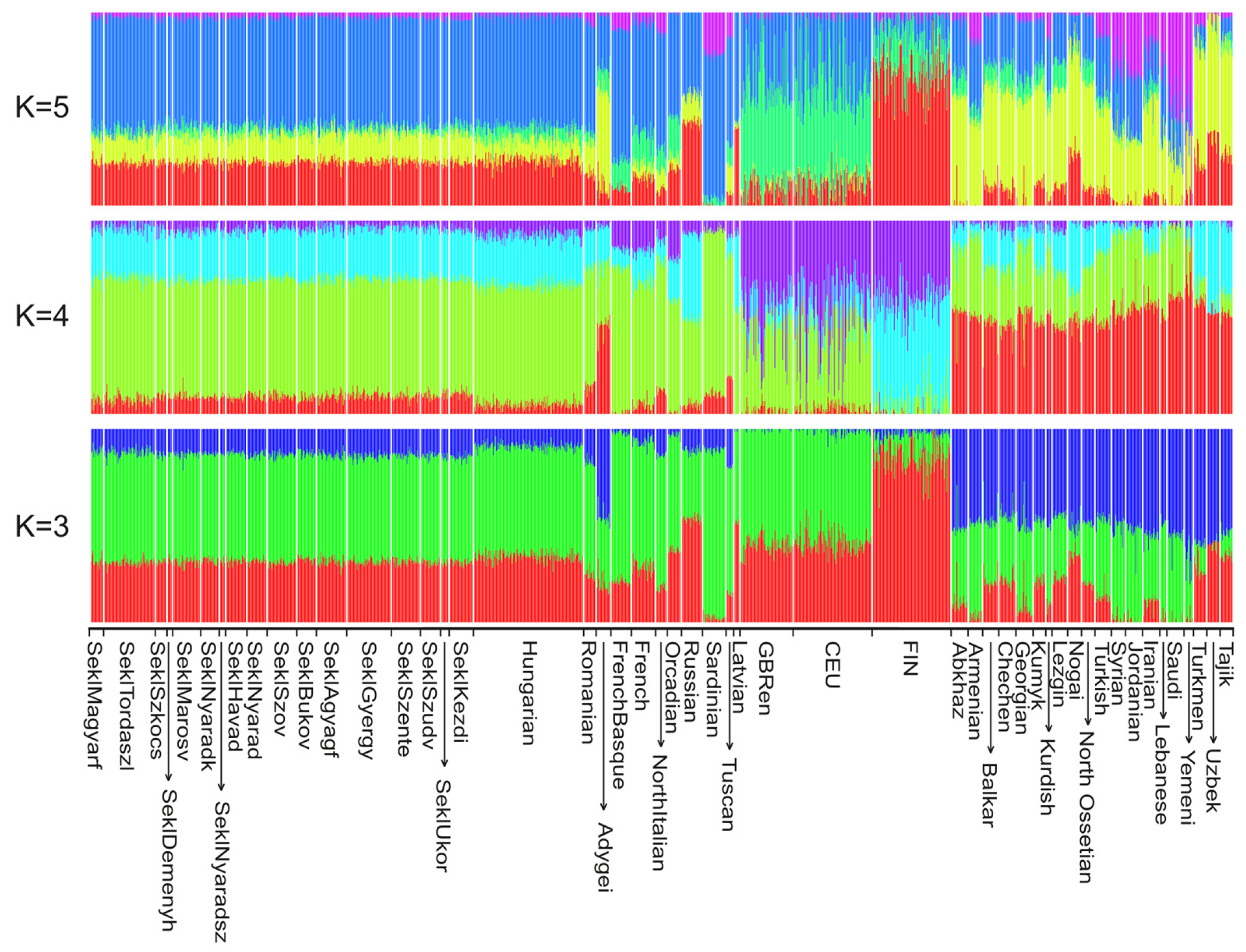

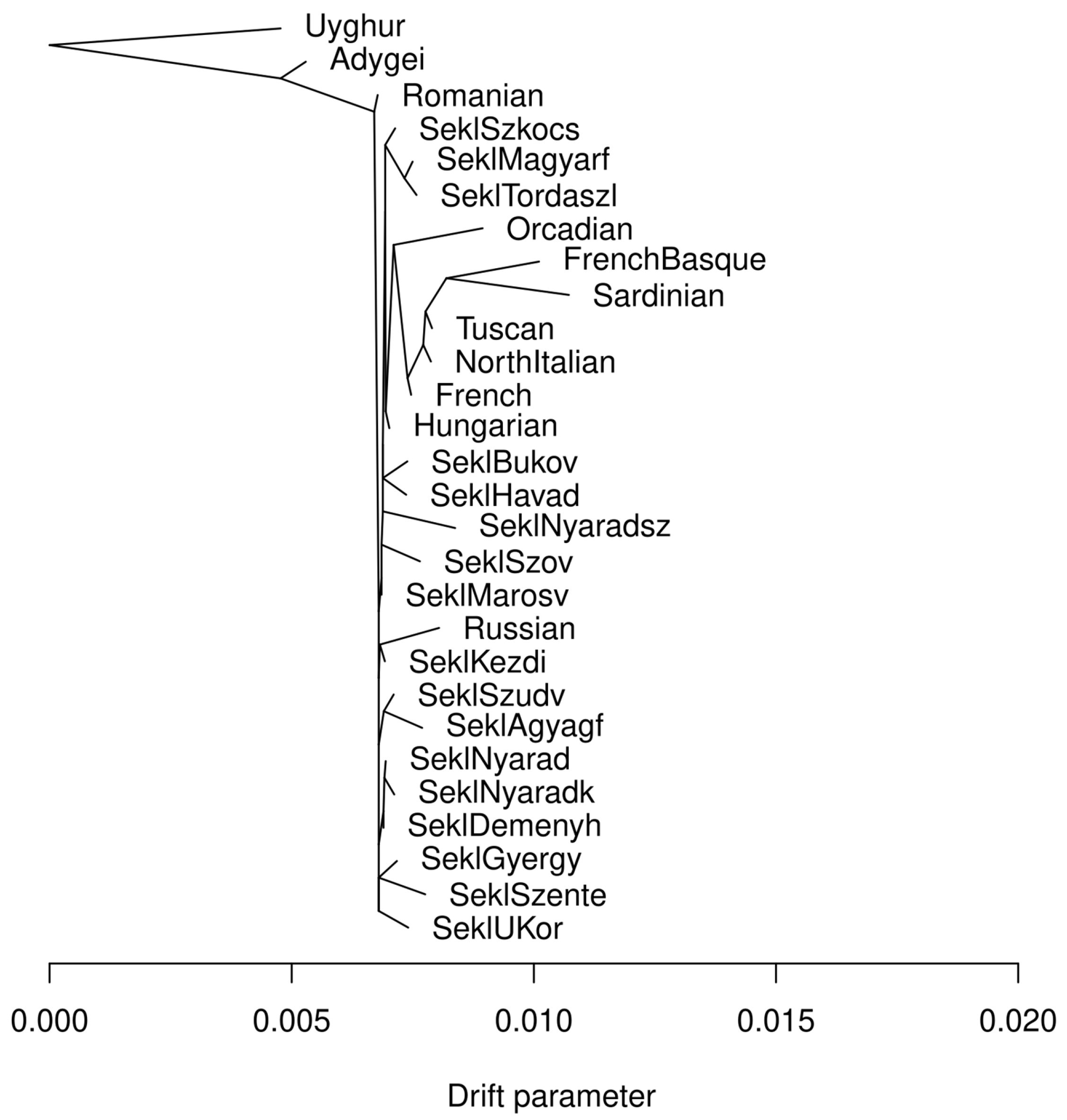

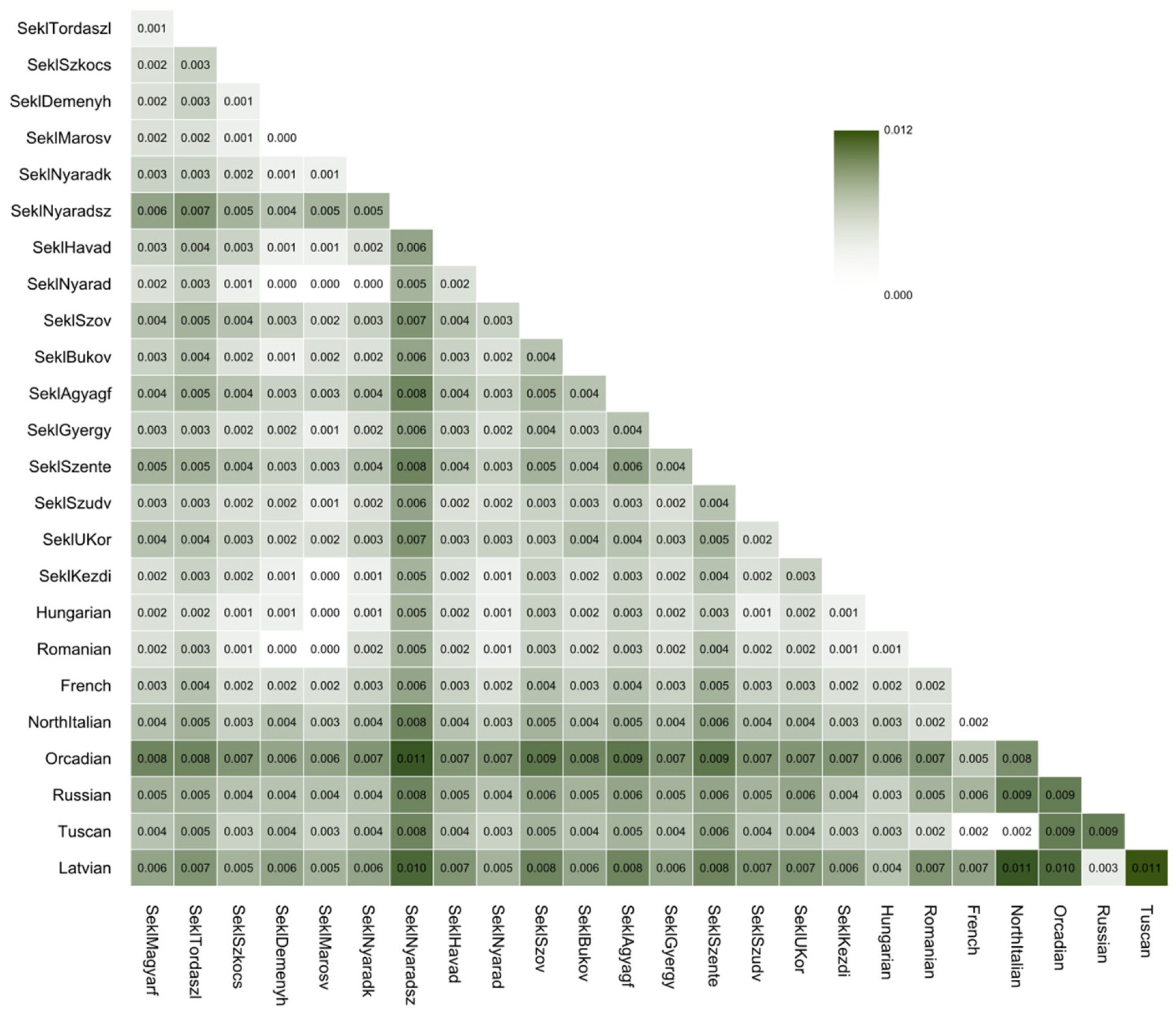

3.1. Allele Frequency-Based Population Structure Analysis

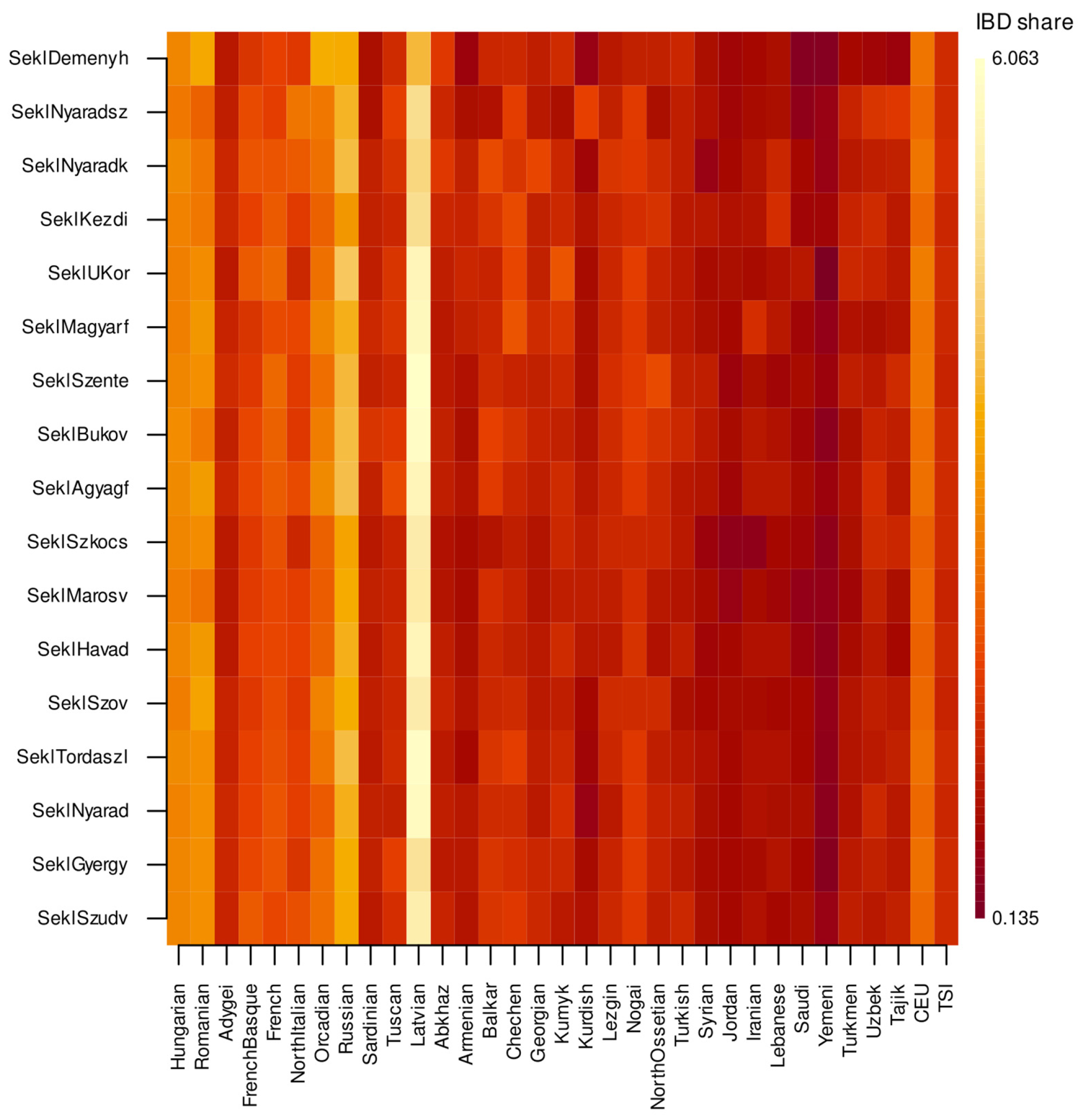

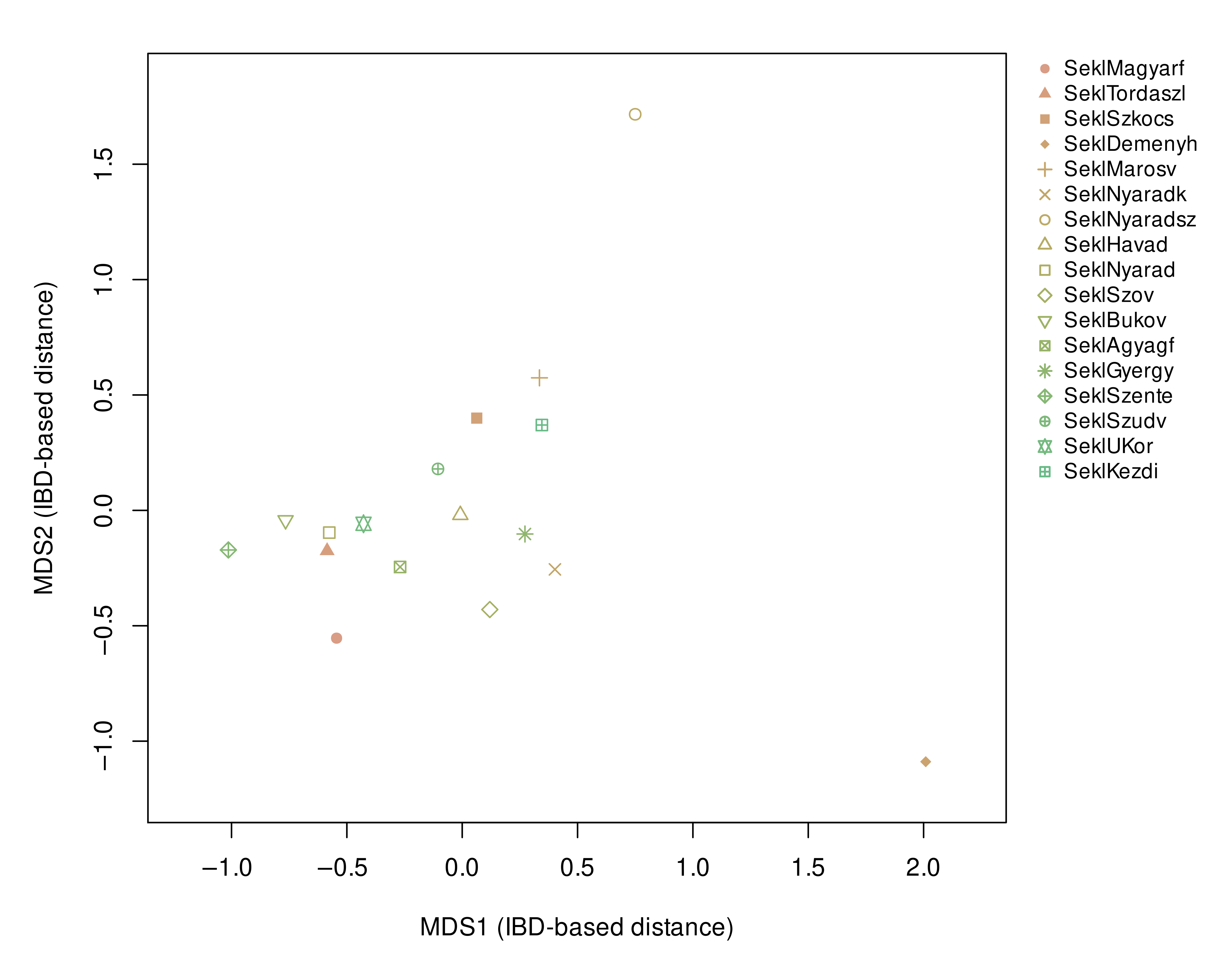

3.2. Identity-by-Descent Segment Analyses

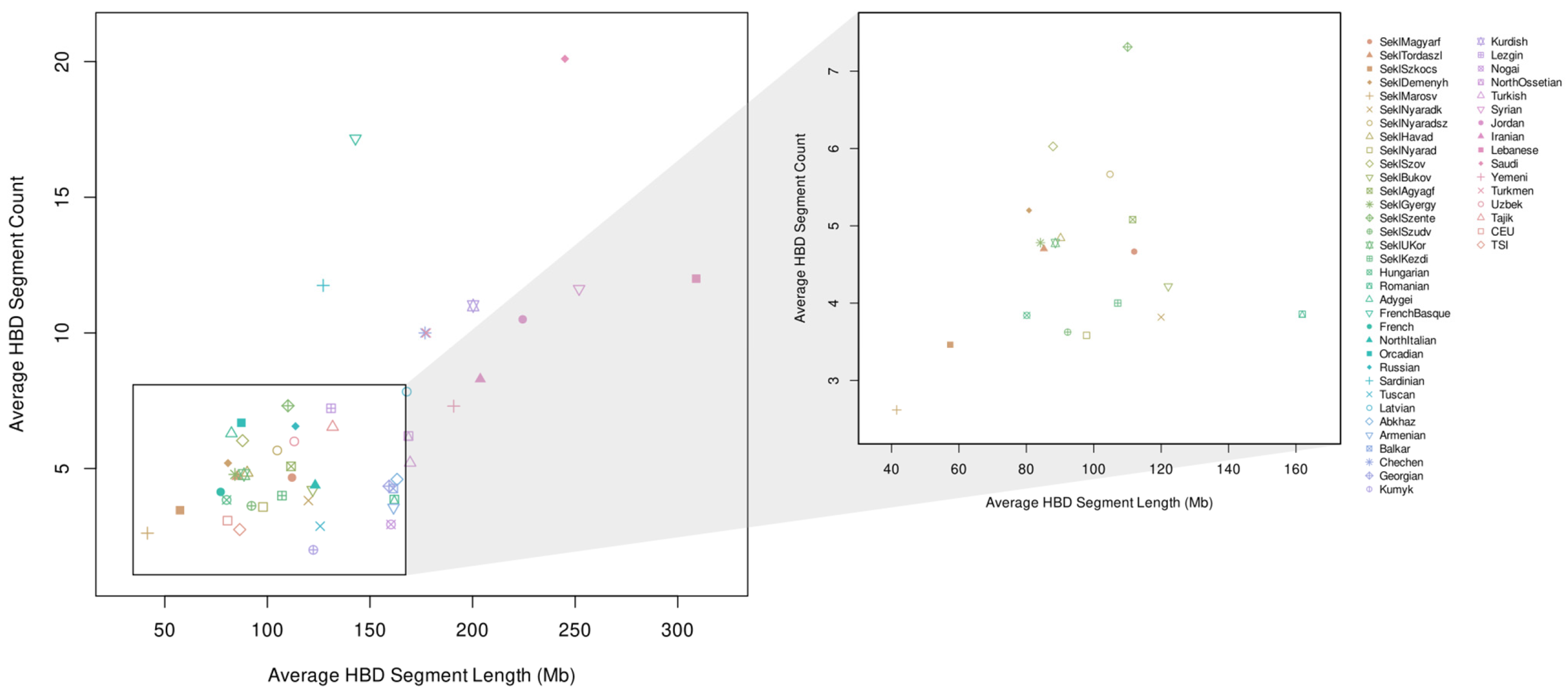

3.3. Autozygosity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| CEU | Utah Residents with Northern and Western European ancestry |

| FIN | Finnish |

| GBRen | British (English only) |

| TSI | Toscani in Italy |

| SeklMagyarf | Magyarfenes |

| SeklTordaszl | Tordaszentlászló |

| SeklSzkocs | Székelykocsárd |

| SeklDemenyh | Deményháza |

| SeklMarosv | Marosvásárhely |

| SeklNyaradk | Nyárádköszvényes |

| SeklNyaradsz | Nyárádszentimre |

| SeklHavad | Havad |

| SeklNyarad | Nyárádmente |

| SeklSzov | Szováta |

| SeklBukov | Bukovina region |

| SeklAgyagf | Agyagfalva |

| SeklGyergy | Gyergyószentmiklós |

| SeklSzente | Szentegyháza |

| SeklSzudv | Székelyudvarhely |

| SeklUKor | Unitarians from Korond |

| SeklKezdi | Kézdivásárhely |

| HuGe-F | Human Genomics Facility |

| HWE | Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium |

| MAF | Minor allele frequency |

| HapMap | International Haplotype Map |

| HGDP-CEPH | Human Genome Diversity Project-Centre d’Étude du Polymorphisme HHumain |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| FST | Pairwise fixation index |

| CV | Cross-validation |

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium |

| IBD | Identity-by-descent |

| HBD | Homozygosity-by-descent |

| VCF | Variant Call Format |

| MDS | Multidimensional scaling |

References

- Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; Mittnik, A.; Renaud, G.; Mallick, S.; Kirsanow, K.; Sudmant, P.H.; Schraiber, J.G.; Castellano, S.; Lipson, M.; et al. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature 2014, 513, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Llamas, B.; Brandt, G.; Nordenfelt, S.; Harney, E.; Stewardson, K.; et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 2015, 522, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, I.; Alpaslan-Roodenberg, S.; Posth, C.; Szecsenyi-Nagy, A.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Olalde, I.; Broomandkhoshbacht, N.; Candilio, F.; Cheronet, O.; et al. The genomic history of southeastern Europe. Nature 2018, 555, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allentoft, M.E.; Sikora, M.; Sjogren, K.G.; Rasmussen, S.; Rasmussen, M.; Stenderup, J.; Damgaard, P.B.; Schroeder, H.; Ahlstrom, T.; Vinner, L.; et al. Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature 2015, 522, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, C.; Jones, E.R.; Teasdale, M.D.; McLaughlin, R.L.; Gonzalez-Fortes, G.; Mattiangeli, V.; Domboroczki, L.; Kovari, I.; Pap, I.; Anders, A.; et al. Genome flux and stasis in a five millennium transect of European prehistory. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaky, V.; Gerber, D.; Koncz, I.; Csiky, G.; Mende, B.G.; Szeifert, B.; Egyed, B.; Pamjav, H.; Marcsik, A.; Molnar, E.; et al. Genetic insights into the social organisation of the Avar period elite in the 7th century AD Carpathian Basin. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, C.; Balanovsky, O.; Lukianova, E.; Kahbatkyzy, N.; Flegontov, P.; Zaporozhchenko, V.; Immel, A.; Wang, C.C.; Ixan, O.; Khussainova, E.; et al. The genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 966–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Róna-Tas, A. Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History; Central European University Press: Budapest, Hungary, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Makkai, L. Hystory Transylvania; 2001; Volume I, pp. 1–331. ISBN 0-88033-479-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dreisziger, N. The Székelys: Ancestors of Today’s Hungarians? A New Twist to Magyar Prehistory. Hung. Stud. Rev. 2009, XXXVI, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Fóthi, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Fehér, T.; Gugora, A.; Fóthi, Á.; Biró, O.; Keyser, C. Genetic analysis of male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian paternal lineages of the conquering Hungarian tribes. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenthal, G.; Busby, G.B.J.; Band, G.; Wilson, J.F.; Capelli, C.; Falush, D.; Myers, S. A genetic atlas of human admixture history. Science 2014, 343, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egyed, B.; Brandstatter, A.; Irwin, J.A.; Padar, Z.; Parsons, T.J.; Parson, W. Mitochondrial control region sequence variations in the Hungarian population: Analysis of population samples from Hungary and from Transylvania (Romania). Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2007, 1, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csanyi, B.; Bogacsi-Szabo, E.; Tomory, G.; Czibula, A.; Priskin, K.; Csosz, A.; Mende, B.; Lango, P.; Csete, K.; Zsolnai, A.; et al. Y-chromosome analysis of ancient Hungarian and two modern Hungarian-speaking populations from the Carpathian Basin. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2008, 72, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, V.; Banfai, Z.; Sumegi, K.; Buki, G.; Szabo, A.; Magyari, L.; Miseta, A.; Kasler, M.; Melegh, B. Genome-Wide Marker Data-Based Comparative Population Analysis of Szeklers From Korond, Transylvania, and From Transylvania Living Non-Szekler Hungarians. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 841769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, N.; Moorjani, P.; Luo, Y.; Mallick, S.; Rohland, N.; Zhan, Y.; Genschoreck, T.; Webster, T.; Reich, D. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics 2012, 192, 1065–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D.J.; Hellenthal, G.; Myers, S.; Falush, D. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.C.; Chow, C.C.; Tellier, L.C.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.M.; Lee, J.J. Second-generation PLINK: Rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International HapMap, C.; Frazer, K.A.; Ballinger, D.G.; Cox, D.R.; Hinds, D.A.; Stuve, L.L.; Gibbs, R.A.; Belmont, J.W.; Boudreau, A.; Hardenbol, P.; et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature 2007, 449, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manichaikul, A.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Rich, S.S.; Daly, K.; Sale, M.; Chen, W.M. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2867–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli-Sforza, L.L. The Human Genome Diversity Project: Past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, H.M.; de Toma, C.; Cazes, L.; Legrand, M.F.; Morel, V.; Piouffre, L.; Bodmer, J.; Bodmer, W.F.; Bonne-Tamir, B.; Cambon-Thomsen, A.; et al. A human genome diversity cell line panel. Science 2002, 296, 261–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.A.; Pritchard, J.K.; Weber, J.L.; Cann, H.M.; Kidd, K.K.; Zhivotovsky, L.A.; Feldman, M.W. Genetic structure of human populations. Science 2002, 298, 2381–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.A.; Mahajan, S.; Ramachandran, S.; Zhao, C.; Pritchard, J.K.; Feldman, M.W. Clines, clusters, and the effect of study design on the inference of human population structure. PLoS Genet. 2005, 1, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergstrom, A.; McCarthy, S.A.; Hui, R.; Almarri, M.A.; Ayub, Q.; Danecek, P.; Chen, Y.; Felkel, S.; Hallast, P.; Kamm, J.; et al. Insights into human genetic variation and population history from 929 diverse genomes. Science 2020, 367, eaay5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusbayev, B.; Metspalu, M.; Metspalu, E.; Valeev, A.; Litvinov, S.; Valiev, R.; Akhmetova, V.; Balanovska, E.; Balanovsky, O.; Turdikulova, S.; et al. The genetic legacy of the expansion of Turkic-speaking nomads across Eurasia. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behar, D.M.; Metspalu, M.; Baran, Y.; Kopelman, N.M.; Yunusbayev, B.; Gladstein, A.; Tzur, S.; Sahakyan, H.; Bahmanimehr, A.; Yepiskoposyan, L.; et al. No evidence from genome-wide data of a Khazar origin for the Ashkenazi Jews. Hum. Biol. 2013, 85, 859–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genomes Project, C.; Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A.; et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, N.; Price, A.L.; Reich, D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2, e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, D.H.; Novembre, J.; Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, B.L.; Browning, S.R. A fast, powerful method for detecting identity by descent. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 88, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S. PLINK/SEQ: A Library for the Analysis of Genetic Variation Data. Available online: https://zzz.bwh.harvard.edu/plinkseq/start-pseq.shtml (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Browning, B.L.; Browning, S.R. Improving the accuracy and efficiency of identity-by-descent detection in population data. Genetics 2013, 194, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmon, G.; Hao, L.; Pe’er, I.; Velez, C.; Pearlman, A.; Palamara, P.F.; Morrow, B.; Friedman, E.; Oddoux, C.; Burns, E.; et al. Abraham’s children in the genome era: Major Jewish diaspora populations comprise distinct genetic clusters with shared Middle Eastern Ancestry. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 86, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, S.R.; Browning, B.L. Accurate Non-parametric Estimation of Recent Effective Population Size from Segments of Identity by Descent. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 97, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Szabó, A.; Bánfai, Z.; Sümegi, K.; Ádám, V.; Gallyas, F.; Kásler, M.; Melegh, B. Uncovering the Genetic Structure of the Sekler Population in Transylvania Through Genome-Wide Autosomal Data. Genes 2026, 17, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010030

Szabó A, Bánfai Z, Sümegi K, Ádám V, Gallyas F, Kásler M, Melegh B. Uncovering the Genetic Structure of the Sekler Population in Transylvania Through Genome-Wide Autosomal Data. Genes. 2026; 17(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzabó, András, Zsolt Bánfai, Katalin Sümegi, Valerián Ádám, Ferenc Gallyas, Miklós Kásler, and Béla Melegh. 2026. "Uncovering the Genetic Structure of the Sekler Population in Transylvania Through Genome-Wide Autosomal Data" Genes 17, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010030

APA StyleSzabó, A., Bánfai, Z., Sümegi, K., Ádám, V., Gallyas, F., Kásler, M., & Melegh, B. (2026). Uncovering the Genetic Structure of the Sekler Population in Transylvania Through Genome-Wide Autosomal Data. Genes, 17(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010030