Multi-Omics Analysis Identifies the Key Defence Pathways in Chinese Cabbage Responding to Black Spot Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Experimental Treatment

2.2. Pathogen Inoculation and Disease Scoring

2.3. RNA Sequencing

2.4. Transcriptomic Data Analysis

2.5. Metabolite Extraction and Data Analysis

2.6. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

2.7. VIGS-Mediated Silencing of BraPBL

2.8. Generation of BraPBL Overexpressing Plants

2.9. Subcellular Co-Localization

2.10. NBT Staining

2.11. Trypan Blue Staining

3. Results

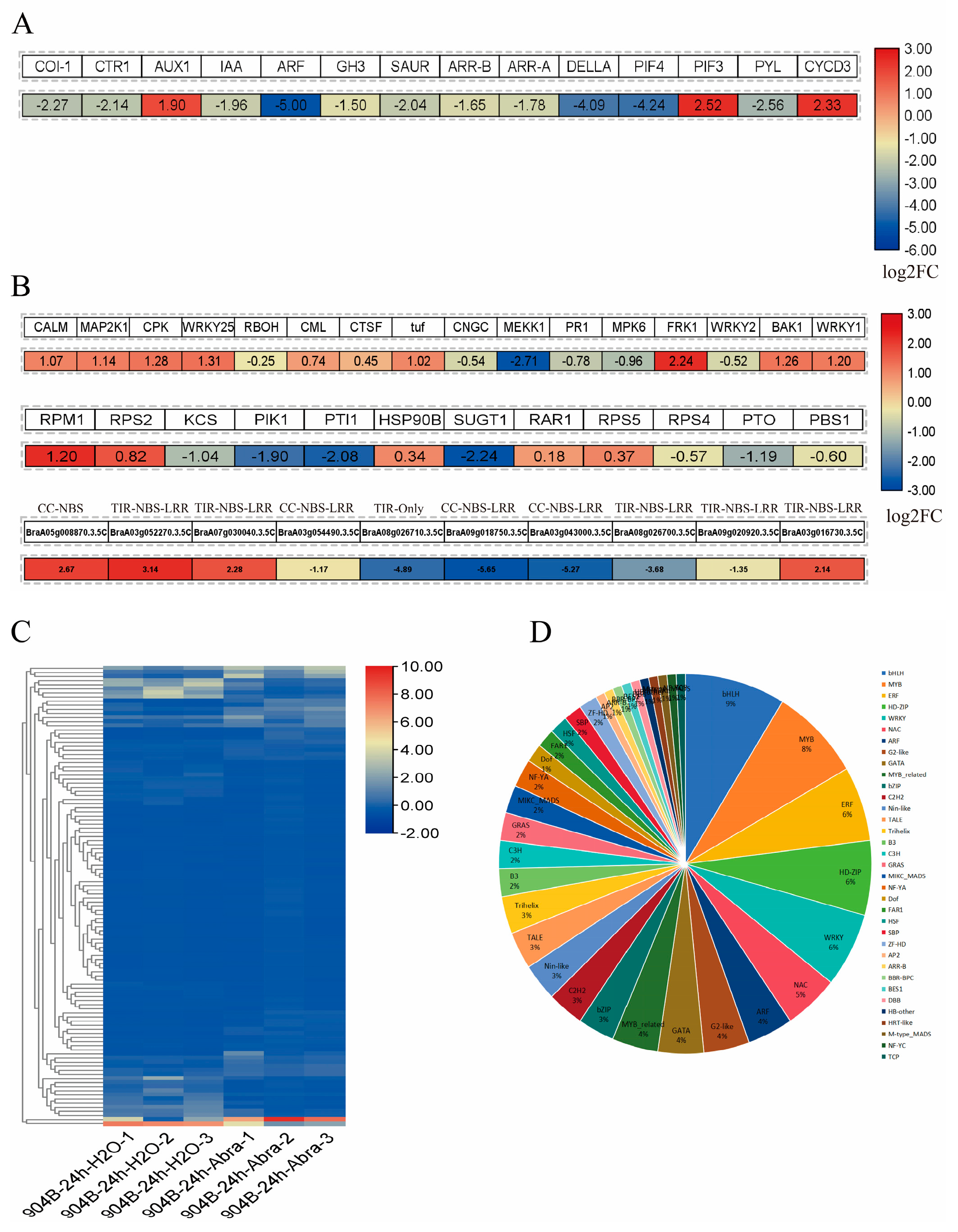

3.1. Differentially Expressed Genes in Chinese Cabbage Responding to Black Spot Disease

3.2. Responses of Hormone-Signalling and Defence-Related Genes in Chinese Cabbage to Black Spot Disease

3.3. Differentially Expressed Metabolites in Chinese Cabbage Responding to Black Spot Disease

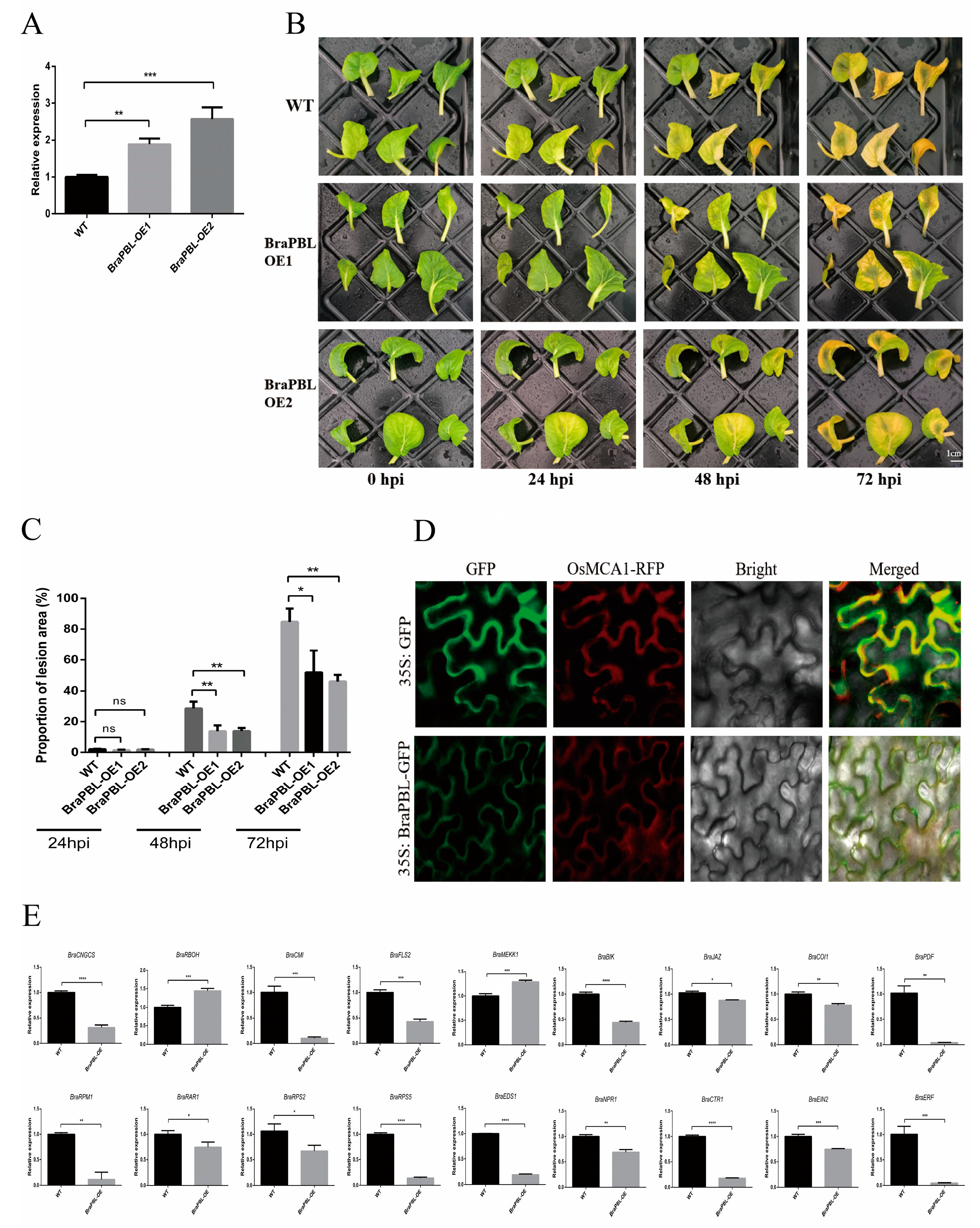

3.4. Silencing BraPBL Compromises Resistance in Chinese Cabbage

3.5. Overexpression of BraPBL Enhances Resistance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, J.; Hong, Y. Chinese cabbage: An emerging model for functional genomics in leafy vegetable crops. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazauskienė, I.; Petraitienė, E.; Brazauskas, G.; Semaškienė, R. Medium-term trends in dark leaf and pod spot epidemics in Brassica napus and Brassica rapa in Lithuania. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2011, 118, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.D.; Meena, R.L.; Chattopadhyay, C.; Kumar, A. Identification of critical stage for disease development and biocontrol of Alternaria blight of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea). J. Phytopathol. 2004, 152, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, J.; Van Tongeren, C.A.M.; Groenenboom-de Haas, B.H.; Van Hoof, R.A.; Driessen, R.; Van Der Heijden, L. Epidemiology of dark leaf spot caused by Alternaria brassicicola and A. brassicae in organic seed production of cauliflower. Plant Pathol. 2010, 59, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.N.; Nan, N.; Lu, B.H.; Xia, W.Y.; Wu, X.Y. Alternaria brassicicola causes a leaf spot on isatis indigotica in China. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, M.; Nowakowska, M.; Niezgoda, A.; Kozik, E. Alternaria black spot of crucifers: Symptoms, importance of disease, and perspectives of resistance breeding. J. Fruit. Ornam. Plant Res. 2012, 76, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macioszek, V.K.; Gapińska, M.; Zmienko, A.; Sobczak, M.; Skoczowski, A.; Oliwa, J.; Kononowicz, A.K. Complexity of Brassica oleracea–Alternaria brassicicola susceptible interaction reveals downregulation of photosynthesis at ultrastructural, transcriptional, and physiological levels. Cells 2020, 9, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runno-Paurson, E.; Lääniste, P.; Nassar, H.; Hansen, M.; Eremeev, V.; Metspalu, L.; Edesi, L.; Kännaste, A.; Niinemets, Ü. Alternaria black spot (Alternaria brassicae) infection severity on Cruciferous oilseed crops. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpherson-Jones, F.M.; Phelps, K. Climatic factors influencing spore production in Alternaria brassicae and Alternaria brassicicola. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1989, 114, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 16, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatsugai, N.; Igarashi, D.; Mase, K.; Lu, Y.; Tsuda, Y.; Chakravarthy, S.; Wei, H.L.; Foley, J.W.; Collmer, A.; Glazebrook, J.; et al. A plant effector-triggered immunity signaling sector is inhibited by pattern-triggered immunity. EMBO 2017, 36, 2758–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, M.C. Hypersensitive response-related death. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000, 44, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasu, K.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Regulators of cell death in disease resistance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000, 44, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorang, J.M.; Sweat, T.A.; Wolpert, T.J. Plant disease susceptibility conferred by a “resistance” gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 11, 14861–14866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm, S.T.; Coaker, G.; Day, B.; Staskawicz, B.J. Host-microbe interactions: Shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 2006, 24, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Sun, J.; Shabbir, S.; Khattak, W.A.; Ren, G.; Nie, X.; Bo, Y.; Javed, Q.; Du, D.; Sonne, C. A review of plants strategies to resist biotic and abiotic environmental stressors. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duhan, L.; Pasrija, R. Unveiling exogenous potential of phytohormones as sustainable arsenals against plant pathogens: Molecular signaling and crosstalk insights. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Kashtoh, H.; Panda, J.; Rustagi, S.; Mohanta, Y.K.; Singh, N.; Baek, K.H. From hormones to harvests: A pathway to strengthening plant resilience for achieving sustainable development goals. Plants 2025, 14, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, H. The role of sterols in plant growth and development. Prog. Lipid Res. 2003, 42, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.; Szakiel, A. The role of sterols in plant response to abiotic stress. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, C.; Oldroyd, G.E. Plant signalling in symbiosis and immunity. Nature 2017, 543, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Ma, X.; Shan, L.; He, P. Big roles of small kinases: The complex functions of receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases in plant immunity and development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2013, 55, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehti-Shiu, M.D.; Zou, C.; Hanada, K.; Shiu, S.H. Evolutionary history and stress regulation of plant receptor-like kinase/pelle genes. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, S.; Giri, J.; Dansana, P.K.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A.K. The receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase (OsRLCK) gene family in rice: Organization, phylogenetic relationship, and expression during development and stress. Mol. Plant 2008, 1, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, J. Regulation of plant responses to biotic and abiotic stress by receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases. Stress. Biol. 2022, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hailemariam, S.; Liao, C.J.; Mengiste, T. Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases: Orchestrating plant cellular communication. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 1113–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhou, J.M. Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases: Central players in plant receptor kinase-mediated signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Yamada, K.; Kawasaki, T. Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases are pivotal components in pattern recognition receptor-mediated signaling in plant immunity. Plant Signal Behav. 2013, 8, e25662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zhang, H.; Fan, W.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, B. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Chinese cabbage J405 reveals underlying high resistance to Alternaria brassicicola-induced black spot disease. Plant Stress. 2025, 19, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccard, J.; Rutledge Douglas, N.A. Consensus orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) strategy for multiblock Omics data fusion. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 769, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalystR: An R package for flexible and reproducible analysis of metabolomics data. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 4313–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−∆∆Ct method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Liu, W.; Jiang, J.; Xu, L.; Huang, L.; Cao, J. Efficient genome editing of Brassica campestris based on the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2019, 294, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurusu, T.; Nishikawa, D.; Yamazaki, Y.; Gotoh, M.; Nakano, M.; Hamada, H.; Yamanaka, T.; Iida, K.; Nakagawa, Y.; Saji, H.; et al. Plasma membrane protein OsMCA1 is involved in regulation of hypo-osmotic shock-induced Ca2+ influx and modulates generation of reactive oxygen species in cultured rice cells. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhou, S.; Yang, D.; Fan, Z. Revealing shared and distinct genes responding to JA and SA signaling in Arabidopsis by meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 908. [Google Scholar]

- Caarls, L.; Pieterse, C.M.; Van-Wees, S.C. How salicylic acid takes transcriptional control over jasmonic acid signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 25, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoel, S.H.; Johnson, J.S.; Dong, X. Regulation of tradeoffs between plant defenses against pathogens with different lifestyles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 18842–18847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flors, V.; Ton, J.; Van-Doorn, R.; Jakab, G.; García-Agustín, P.; Mauch-Mani, B. Interplay between JA, SA and ABA signalling during basal and induced resistance against Pseudomonas syringae and Alternaria brassicicola. Plant J. 2008, 54, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, M.; Das, S.; Saha, U.; Chatterjee, M.; Bannerjee, K.; Basu, D. Salicylic acid-mediated establishment of the compatibility between Alternaria brassicicola and Brassica juncea is mitigated by abscisic acid in Sinapis alba. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 70, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, A.; Maity, A.; Mazumder, M.; Mondal, B.; Mukherjee, A.; Ghosh, S.; Ray, P.; Polley, S.; Dastidar, S.G.; Basu, D. Overexpression of LYK4, a lysin motif receptor with non-functional kinase domain, enhances tolerance to Alternaria brassicicola and increases trichome density in Brassica juncea. Plant Sci. 2021, 309, 110953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Cao, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhao, J.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Activation of the indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase GH3-8 suppresses expansin expression and promotes salicylate- and jasmonate-independent basal immunity in rice. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, Z.; Hossain, M.R.; Yang, S.; Shi, G.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tian, B.; et al. Root transcriptome and metabolome profiling reveal key phytohormone-related genes and pathways involved clubroot resistance in Brassica rapa L. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 759623. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig-Müller, J. Auxin homeostasis, signaling, and interaction with other growth hormones during the clubroot disease of Brassicaceae. Plant Signal Behav. 2014, 9, e28593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erb, M.; Kliebenstein, D.J. Plant secondary metabolites as defenses, regulators, and primary metabolites: The blurred functional trichotomy. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaynab, M.; Fatima, M.; Abbas, S.; Sharif, Y.; Umair, M.; Zafar, M.H.; Bahadar, K. Role of secondary metabolites in plant defense against pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 124, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, Q.; Xie, H.; Li, W. The function of secondary metabolites in resisting stresses in horticultural plants. Fruit Res. 2024, 4, e021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.; Arshad, M.; Khan, M.Z.; Amjad, M.S.; Sadaf, H.M.; Riaz, I.; Sabir, S.; Ahmad, N.; Sabaoon. Secondary metabolites and their multidimensional prospective in plant life. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017, 6, 205−214. [Google Scholar]

- Rahier, A. Dissecting the sterol C-4 demethylation process in higher plants. From structures and genes to catalytic mechanism. Steroids 2011, 76, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Fu, X.; Chu, Y.; Wu, P.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Tian, H.; Zhu, B. Biosynthesis and the roles of plant sterols in development and stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, P.; Persson, S.; Moreno-Pescador, G.; Noack, L.C. Sterols in plant biology-advances in studying membrane dynamics. Cell Surf. 2025, 13, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosjean, K.; Mongrand, S.; Beney, L.; Simon-Plas, F.; Gerbeau-Pissot, P. Differential effect of plant lipids on membrane organization: Specificities of phytosphingolipids and phytosterols. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 5810–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Muriefah, S.S. Effect of sitosterol on growth, metabolism and protein pattern of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants grown under salt stress conditions. Intl. J. Agric. Crop Sci. 2015, 8, 94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Elkeilsh, A.; Awad, Y.M.; Soliman, M.H.; Abu-Elsaoud, A.; Abdelhamid, M.T.; El-Metwally, I.M. Exogenous application of β-sitosterol mediated growth and yield improvement in water-stressed wheat (Triticum aestivum) involves up-regulated antioxidant system. J. Plant Res. 2019, 132, 881–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Liu, J.; Kou, C.; Lu, J.; Zhang, H.; Song, W.; Li, Y.; Xue, Z.; Hua, X. Deciphering the network of cholesterol biosynthesis in paris polyphylla laid a base for efficient diosgenin production in plant chassis. Metab. Eng. 2023, 76, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajguz, A.; Chmur, M.; Gruszka, D. Comprehensive overview of the brassinosteroid biosynthesis pathways: Substrates, products, inhibitors, and connections. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, M.; He, P.; Zhang, Y. Loss-of-function of Arabidopsis receptor-like kinase BIR1 activates cell death and defense responses mediated by BAK1 and SOBIR1. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Bai, L.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Shan, W.; Shi, X.; Ma, S.; Fan, J. Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases mediated signaling in plant immunity: Convergence and divergence. Stress. Biol. 2025, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, N.K.; Nagalakshmi, U.; Hurlburt, N.K.; Flores, R.; Bak, A.; Sone, P.; Ma, X.; Song, G.; Walley, J.; Shan, L.; et al. The receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase BIK1 localizes to the nucleus and regulates defense hormone expression during plant innate immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, P.; Nakagami, H.; Bluhm, B.; Abuqamar, S.; Chen, X.; Salmeron, J.; Dietrich, R.A.; Hirt, H.; Mengiste, T. The membrane-anchored BOTRYTIS-INDUCED KINASE1 plays distinct roles in Arabidopsis resistance to necrotrophic and biotrophic pathogens. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Xie, Q.; Tian, X.; Zhou, J.M. BIK1 interacts with PEPRs to mediate ethylene-induced immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 6205–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Zang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Song, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.; Yi, Y.; Zhu, B.; Fu, D.; et al. Atomato receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase SlZRK1, acts as a negative regulator in wound-induced jasmonic acid accumulation insect resistance. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 7285–7300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Xiang, T.; Liu, Z.; Laluk, K.; Ding, X.; Zou, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; et al. Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases integrate signaling from multiple plant immune receptors and are targeted by a Pseudomonas syringae effector. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, J.; Chen, K.; Han, Y.; Wang, R.; Zou, Y.; Du, M.; Lu, D. BIK1 protein homeostasis is maintained by the interplay of different ubiquitin ligases in immune signaling. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, W.; Zhang, H.; Fan, W.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, B. Multi-Omics Analysis Identifies the Key Defence Pathways in Chinese Cabbage Responding to Black Spot Disease. Genes 2026, 17, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010115

Yan W, Zhang H, Fan W, Liu X, Huang Z, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Wang C, Zhang B. Multi-Omics Analysis Identifies the Key Defence Pathways in Chinese Cabbage Responding to Black Spot Disease. Genes. 2026; 17(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Wenyuan, Hong Zhang, Weiqiang Fan, Xiaohui Liu, Zhiyin Huang, Yong Wang, Yerong Zhu, Chaonan Wang, and Bin Zhang. 2026. "Multi-Omics Analysis Identifies the Key Defence Pathways in Chinese Cabbage Responding to Black Spot Disease" Genes 17, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010115

APA StyleYan, W., Zhang, H., Fan, W., Liu, X., Huang, Z., Wang, Y., Zhu, Y., Wang, C., & Zhang, B. (2026). Multi-Omics Analysis Identifies the Key Defence Pathways in Chinese Cabbage Responding to Black Spot Disease. Genes, 17(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010115