Comparative Chromosomal Mapping of the 18S rDNA Loci in True Bugs: The First Data for 13 Genera of the Infraorders Cimicomorpha and Pentatomomorpha (Hemiptera, Heteroptera)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

- Chromosomal mapping of 18S rDNA clusters

- Infraorder Cimicomorpha

- Superfamily Miroidea

- Family Miridae

- Subfamily Mirinae

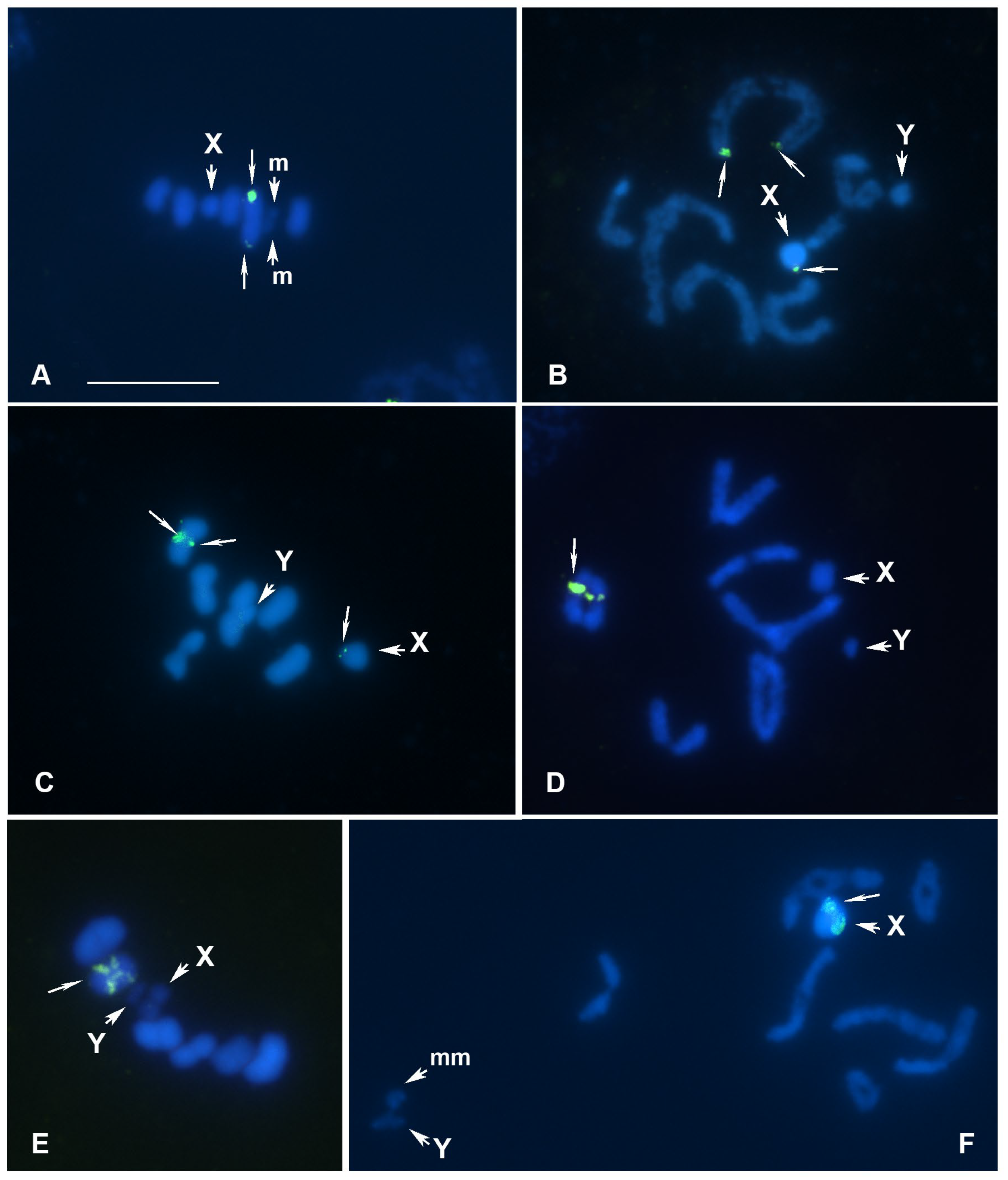

- Horistus orientalis, meioformula: n = 16AA + X + Y (Figure 1A,B)

- Mimocoris rugicollis, meioformula: n = 13AA + X + Y (Figure 1C)

- Infraorder Pentatomomorpha

- Superfamily Coreoidea

- Family Rhopalidae

- Subfamily Rhopalinae

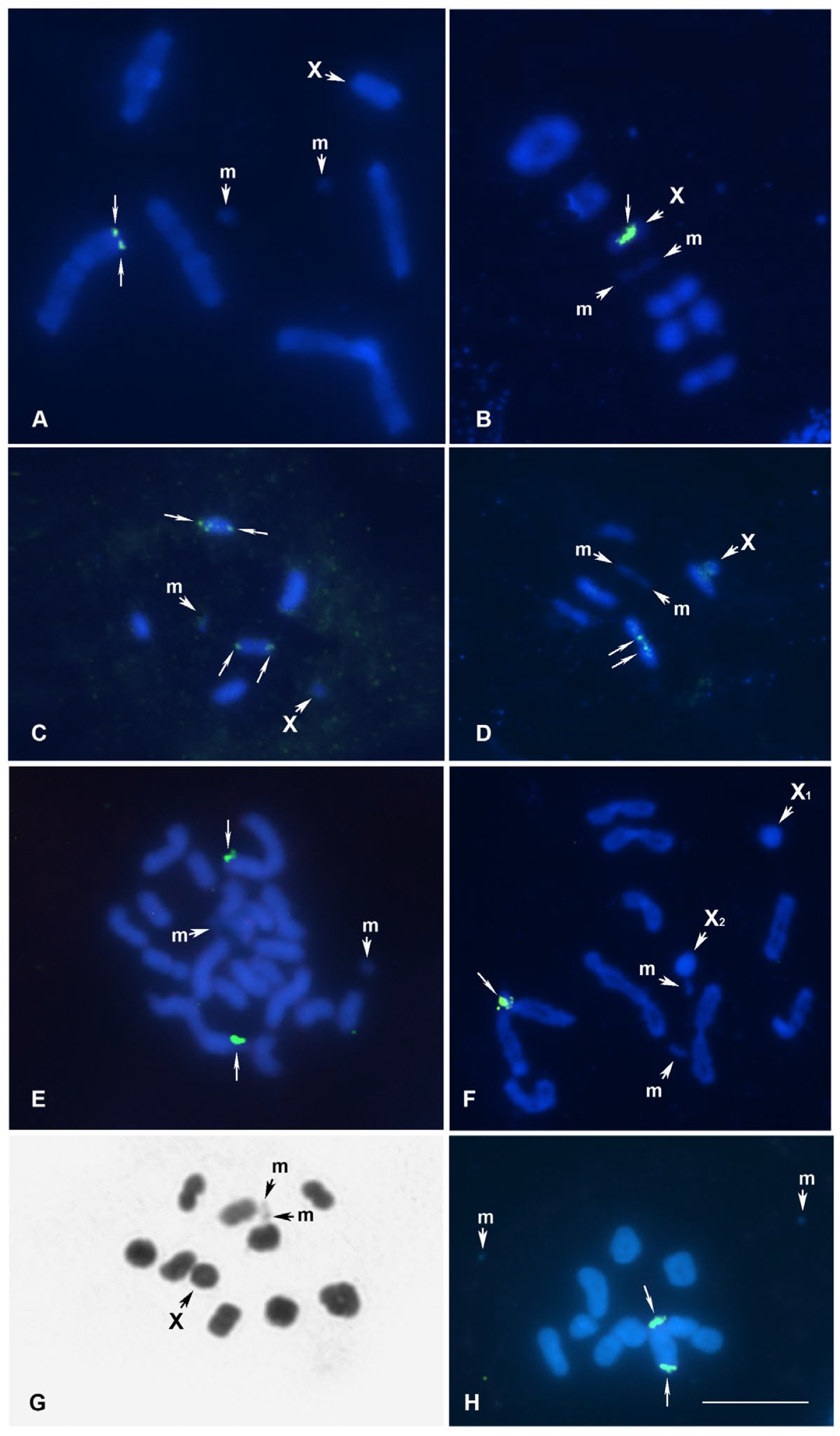

- Brachycarenus tigrinus, meioformula: n = 5AA + 2m + X (Figure 2A)

- Corizus hyoscyami, meioformula: n = 5AA + 2m + X (Figure 2B)

- Liorhyssus hyalinus, meioformula: n = 5AA + 2m + X (Figure 2C)

- Stictopleurus abutilon, meioformula: n = 5AA + 2m + X (Figure 2D)

- Family Coreidae

- Subfamily Coreinae

- Centrocoris spiniger, meioformula: 2n = 18A + 2m + X (Figure 2E)

- Coreus marginatus, meioformula: n = 9AA + 2m + X1 + X2 (Figure 2F)

- Homoeocerus graminis, meioformula: n = 9AA + 2m + X (Figure 2G,H)

- Family Stenocephalidae

- Dicranocephalus agilis, meioformula: n = 5AA + 2m + X (Figure 3A)

- Superfamily Pentatomoidea

- Family Pentatomidae

- Subfamily Pentatominae

- Piezodorus hybneri, meioformula: n = 6AA + X+Y (Figure 3B,C)

- Superfamily Lygaeoidea

- Family Lygaeidae

- Subfamily Lygaeinae

- Lygaeus equestris, meioformula: n = 6AA + X+Y (Figure 3D,E)

- Family Rhyparochromidae

- Subfamily Rhyparochrominae

- Pterotmetus staphyliniformis, meioformula: n = 7AA + 2m + X+Y (Figure 3F)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Garcia, S.; Leitch, A.R.; Kovařík, A. Intragenomic rDNA variation—The product of concerted evolution, mutation, or something in between? Heredity 2023, 131, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, F.; Guerra, M. Distribution of 45S rDNA sites in chromosomes of plants: Structural and evolutionary implications. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gornung, E. Twenty years of physical mapping of major ribosomal RNA genes across the teleosts: A review of research. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2013, 141, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sochorová, J.; Gálvez, F.; Matyášek, R.; Garcia, S.; Kovařík, A. Analyses of the updated “Animal rDNA loci database” with an emphasis on its new features. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokhman, V.E.; Kuznetsova, V.G. Structure and evolution of ribosomal genes of insect chromosomes. Insects 2024, 15, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štys, P.; Kerzhner, I. The rank and nomenclature of higher taxa in recent Heteroptera. Acta Entomol. Bohemoslov. 1975, 72, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Weirauch, C.; Schuh, R.T.; Cassis, G.; Wheeler, W.C. Revisiting habitat and lifestyle transitions in Heteroptera (Insecta: Hemiptera): Insights from a combined morphological and molecular phylogeny. Cladistics 2019, 35, 67–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, R.T.; Weirauch, C. True Bugs of the World (Hemiptera: Heteroptera). Classification and Natural History, 2nd ed.; Monograph Series 8; Siri Scientific Press: Rochdale, UK, 2020; 767p. [Google Scholar]

- Papeschi, A.G.; Mola, M.L.; Bressa, M.J.; Greizerstein, E.J.; Lía, V.; Poggio, L. Behaviour of ring bivalents in holocentric systems: Alternative sites of spindle attachment in Pachylis argentines and Nezara viruda (Heteroptera). Chromosome Res. 2003, 11, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morielle-Souza, A.; Azeredo-Oliveira, M.T. Differential characterization of holocentric chromosomes in triatomines (Heteroptera, Triatominae) using different staining techniques and fluorescent in situ hybridization. Genet. Mol. Res. 2007, 6, 713–720. [Google Scholar]

- Bressa, M.J.; Papeschi, A.G.; Vítková, M.; Kubíčková, S.; Fuková, I.; Pigozzi, M.I.; Marec, F. Sex chromosome evolution in cotton stainers of the genus Dysdercus (Heteroptera: Pyrrhocoridae). Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2009, 125, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozeva, S.; Kuznetsova, V.G.; Anokhin, B.A. Karyotypes, male meiosis and comparative FISH mapping of 18S ribosomal DNA and telomeric (TTAGG)n repeat in eight species of true bugs (Hemiptera, Heteroptera). Comp. Cytogenet. 2011, 5, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozeva, S.; Anokhin, B.; Kuznetsova, V.G. Bed Bugs (Hemiptera). In Protocols for Cytogenetic Mapping of Arthropod Genomes; Sharakhov, I.V., Ed.; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 285–326. [Google Scholar]

- Panzera, Y.; Pita, S.; Ferreiro, M.J.; Ferrandis, I.; Lages, C.; Pérez, R.; Silva, A.E.; Guerra, M.; Panzera, F. High dynamics of rDNA cluster location in kissing bug holocentric chromosomes (Triatominae, Heteroptera). Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2012, 138, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pita, S.; Panzera, F.; Mora, P.; Vela, J.; Palomeque, T.; Lorite, P. The presence of the ancestral insect telomeric motif in kissing bugs (Triatominae) rules out the hypothesis of its loss in evolutionarily advanced Heteroptera (Cimicomorpha). Comp. Cytogenet. 2016, 10, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pita, S.; Lorite, P.; Cuadrado, A.; Panzera, Y.; De Oliveira, J.; Alevi, K.C.C.; Rosa, J.A.; Freitas, S.P.C.; Gómez-Palacio, A.; Solari, A.; et al. High chromosomal mobility of rDNA clusters in holocentric chromosomes of Triatominae, vectors of Chagas Disease (Hemiptera-Reduviidae). Med. Vet. Entomol. 2022, 36, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardella, V.B.; Fernandes, T.; Vanzela, A.L.L. The conservation of number and location of 18S sites indicates the relative stability of rDNA in species of Pentatomomorpha (Heteroptera). Genome 2013, 56, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardella, V.B.; Fernandes, J.A.M.; Cabral-de-Mello, D.C. Chromosomal evolutionary dynamics of four multigene families in Coreidae and Pentatomidae (Heteroptera) true bugs. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2016, 291, 1919–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, R.B.; Jeangirard, C.; Stoianova, D.; Grozeva, S.; Kuznetsova, V.G. A chromosomal analysis of Nepa cinerea Linnaeus, 1758 and Ranatra linearis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Heteroptera, Nepidae). Comp. Cytogenet. 2017, 11, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadílek, D.; Vilímová, J.; Urfus, T. Peaceful revolution in genome size: Polyploidy in the Nabidae (Heteroptera); autosomes and nuclear DNA content doubling. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 193, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Firmino, T.S.; Alevi, K.C.C.; Itoyama, M.M. Chromosomal divergence and evolutionary inferences in Pentatomomorpha infraorder (Hemiptera, Heteroptera) based on the chromosomal location of ribosomal genes. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapon, D.A.; Kuznetsova, V.G.; Maryańska-Nadachowska, A. A new species of the genus Rhaphidosoma Amyot et Serville, 1843 (Heteroptera, Reduviidae), with data on its chromosome complement. Comp. Cytogenet. 2021, 15, 467–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.F.; Costa, A.L.; Dionísio, J.F.; Cañedo, A.D.; da Rosa, R.; Del Valle Garnero, A.; Ribeiro, J.R.I.; Gunski, R.J. Chromosomal distribution of major rDNA and genome size variation in Belostoma angustum Lauck, B. nessimiani Ribeiro & Alecrim, and B. sanctulum Montandon (Insecta, Heteroptera, Belostomatidae). Genetica 2022, 150, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, N.V.; Golub, V.B.; Anokhin, B.A.; Kuznetsova, V.G. Comparative cytogenetics of lace bugs (Tingidae, Heteroptera): New data and a brief overview. Insects 2022, 13, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golub, N.V.; Maryańska-Nadachowska, A.; Anokhin, B.A.; Kuznetsova, V.G. Expanding the chromosomal evolution understanding of lygaeioid true bugs (Lygaeoidea, Pentatomomorpha, Heteroptera) by classical and molecular cytogenetic analysis. Genes 2023, 14, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardella, V.B.; Cabral-de-Mello, D.C. Uncovering the molecular organization of unusual highly scattered 5S rDNA: The case of Chariesterus armatus (Heteroptera). Gene 2018, 646, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, F.; Correa, A.S.; Bardella, V.B.; Milani, D.; Clarindo, W.R.; Soares, F.A.F.; Carvalho, R.F.; Mondin, M.; Cabral-de-Mello, D.C. Cytogenomic characterization of Euschistus (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) species and strains reveals low chromosomal and repetitive DNAs divergences. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2023, 140, 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.B. The chromosomes in relation to the determination of sex in insects. Science 1905, 22, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueshima, N. Animal Cytogenetics. Insecta 6. Hemiptera II: Heteroptera; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin/Stuttgart, Germany, 1979; Volume 117, 528p. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Cui, Y.; Rédei, D.; Baňař, P.; Xie, Q.; Štys, P.; Damgaard, J.; Chen, P.-P.; Yi, W.-B.; Wang, Y.; et al. Phylogenetic divergences of the true bugs (Insecta: Hemiptera: Heteroptera), with emphasis on the aquatic lineages: The last piece of the aquatic insect jigsaw originated in the Late Permian/Early Triassic. Cladistics 2016, 32, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirauch, C.; Schuh, R.T. Systematics and evolution of Heteroptera: 25 years of progress. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2011, 56, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, A.D.; Fairchild, L.M. A quick-freeze method for making smear slides permanent. Stain Technol. 1953, 28, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozeva, S.; Nokkala, S. Chromosomes and their meiotic behavior in two families of the primitive infraorder Dipsocoromorpha (Heteroptera). Hereditas 1996, 125, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozeva, S.; Anokhin, B.A.; Simov, N.; Kuznetsova, V.G. New evidence for the presence of the telomere motif (TTAGG)n in the family Reduviidae and its absence in the families Nabidae and Miridae (Hemiptera, Cimicomorpha). Comp. Cytogenet. 2019, 13, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsova, V.; Golub, N.; Anokhin, B.; Stoianova, D.; Lukhtanov, V. Diversity of telomeric sequences in true bugs (Heteroptera): New data on the infraorders Pentatomomorpha and Cimicomorpha. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2025, 165, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nokkala, S. The mechanisms behind the regular segregation of the m-chromosomes in Coreus marginatus L. (Coreidae, Hemiptera). Hereditas 1986, 105, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.R.; Scudder, G.G.E. The chromosomes of Dicranocephalus agilis (Hemiptera: Heteroptera). Cytologia 1958, 23, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, G.K. A study of the chromosomes during meiosis in forty-three species of Indian Heteroptera. Proc. Zool. Soc. Bengal 1951, 4, 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nuamah, K.A. Karyotypes of some Ghanaian shield-bugs and the higher systematics of the Pentatomoidea (Hemiptera Heteroptera). Insect Sci. Appl. 1982, 3, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaler-Collander, E. Vergleichend-Karyologische Untersuchungen an Lygaeiden. Acta Zool. Fenn. 1941, 30, 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, K.W. Meiotic conjunctive elements not involving chiasmata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1964, 52, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, S.; Nokkala, C. Achiasmatic male meiosis of collochore type in the heteropteran family Miridae. Hereditas 1986, 105, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Wyniger, D. The Central European Hallodapini (Insecta: Heteroptera: Miridae: Phylinae). Russ. Entomol. J. 2006, 15, 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Schuh, R.T.; Menard, K.L. A revised classification of the Phylinae (Insecta: Heteroptera: Miridae): Arguments for the placement of genera. Am. Mus. Novit. 2013, 3785, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, V.G.; Grozeva, S.; Nokkala, S.; Nokkala, C. Cytogenetics of the true bug infraorder Cimicomorpha (Hemiptera, Heteroptera): A review. ZooKeys 2011, 154, 31–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, H.V.; Castanhole, M.M.U.; Gomes, M.O.; Murakami, A.S.; Souza Firmino, T.S.; Saran, P.S.; Banho, C.A.; Monteiro, L.S.; Silva, J.C.P.; Itoyama, M.M. Meiotic behavior of 18 species from eight families of terrestrial Heteroptera. J. Insect Sci. 2014, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coreoidea SF Team. Coreoidea Species File Online. Available online: http://coreoidea.speciesfile.org/HomePage/Coreoidea/HomePage.aspx (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Xavier, A. Cariologia comparada de alguns Hemipteros Heteropteros (Pentatomoideos e Coreideos). Mem. Estud. Mus. Zool. Univ. Coimbra 1945, 163, 1–105. [Google Scholar]

- Schachow, F. Abhandlungen über haploide Chromosomengarnituren in den Samendrüsen der Hemiptera. Anat. Anz. 1932, 75, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zahniser, J.N.; Henry, T.J.; Schumm, Z.R.; Spears, L.R.; Nischwitz, C.; Scow, B.; Volesky, N. Centrocoris volxemi (Puton) (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Coreidae), first records for North America and second species of the genus in the United States. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 2022, 123, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, H.; Jacobs, D.H.; Moulet, P.; Zarrinnia, V. Family Stenocephalidae Dallas, 1852. In True Bugs (Heteroptera) of the Middle-East; Ghahari, H., Moulet, P., McPherson, J.E., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; McPherson, J.E.; Rab, N.; Bundy, C.S. Systematic relationship between Piezodorus guildinii and P. hybneri (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) and diagnostic characters to separate species. Zootaxa 2019, 4613, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellapé, P.M.; Henry, T.J. Lygaeoidea Species File. Available online: https://lygaeoidea.speciesfile.org/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Cabral-de-Mello, D.C.; Mora, P.; Rico-Porras, J.M.; Ferretti, A.B.S.M.; Palomeque, T.; Lorite, P. The spread of satellite DNAs in euchromatin and insights into the multiple sex chromosome evolution in Hemiptera revealed by repeatome analysis of the bug Oxycarenus hyalinipennis. Insect Mol. Biol. 2023, 32, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, J.F.; da Cruz Baldissera, J.N.; Tiepo, A.N.; Fernandes, J.A.M.; Sosa-Gómez, D.R.; da Rosa, R. New cytogenetic data for three species of Pentatomidae (Heteroptera): Dichelops melacanthus (Dallas, 1851), Loxa viridis (Palisot de Beauvois, 1805), and Edessa collaris (Dallas, 1851). Comp. Cytogenet. 2020, 14, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Number of Specimens Studied, Data and Collection Sites |

|---|---|

| Miridae | |

| Horistus orientalis (Gmelin, 1790) | 1 male, 23 May 2018, Kresna Gorge, Bulgaria (41°45′45″ N, 23°10′9″ E) |

| Mimocoris rugicollis (A. Costa, 1853) | 1 male, 23 May 2018, Kresna Gorge, Bulgaria (41°45′45″ N, 23°10′9″ E) |

| Rhopalidae | |

| Brachicarenus tigrinus (Schilling, 1829) | 4 males, 2 August 2024, Teberda vic., Russia (43°27′22″ N, 41°43′36″ E) |

| Corizus hyoscyami (Linnaeus, 1758) | 2 males, 8 August 2024, Teberda vic., Russia (43°27′22″ N, 41°43′36″ E) |

| Liorhyssus hyalinus (Fabricius, 1794) | 2 males, 23 October 2020, Perga vic., Turkey (36°57′28″ N, 30°51′7″ E) |

| Stictopleurus abutilon Rossi, 1790 | 1 male, 20 August 2024, 20 km N Voronezh, Russia (51°48′60″ N, 39°21′43″ E) |

| Coreidae | |

| Centrocoris spiniger (Fabricius, 1781) | 1 male, 23 May 2018, Kresna Gorge, Bulgaria (41°45′45″ N, 23°10′9″ E) |

| Coreus marginatus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 3 males, 20 August 2024, 20 km N Voronezh, Russia (51°48′60″ N, 39°21′43″ E) |

| Homoeocerus (Anacanthocoris) graminis (Fabricius, 1803) | 1 male, 2 November 2019, mount Popa, Myanmar (20°55′16″ N, 95°15′12″ E) |

| Stenocephalidae | |

| Dicranocephalus agilis (Scopoli, 1763) | 1 male, 25 June 2021, Sevan vic., Armenia (40°33′42″ N, 44°58′4″ E) |

| Pentatomidae | |

| Piezodorus hybneri (Gmelin, 1790) | 1 male, 31 October 2019, Pagan, Myanmar (21°10′16″ N, 94°51′36″ E) |

| Lygaeidae | |

| Lygaeus equestris (Linnaeus, 1758) | 2 males, 20 August 2024, 20 km N Voronezh, Russia (51°48′60″ N, 39°21′43″ E) |

| Rhyparochromidae | |

| Pterotmetus staphyliniformis (Schilling, 1829) | 1 male, 20 August 2024, 20 km N Voronezh, Russia (51°48′60″ N, 39°21′43″ E) |

| Taxa | 2n and Karyotype Formula * | Location of 18S rDNA | Published Data on Chromosome Numbers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIMICOMORPHA | ||||

| Miroideа | ||||

| Miridae | ||||

| Mirinae | ||||

| Horistus orientalis | 34 (32A + XY) | X | [34] ** | |

| Mimocoris rugicollis | 28 (26A + XY) | X | Absent | |

| PENTATOMOMORPHA | ||||

| Coreoidea | ||||

| Rhopalidae | ||||

| Rhopalinae | ||||

| Brachycarenus tigrinus | 13 (10A + 2m + X) | AA1 | [35] | |

| Corizus hyoscyami | 13 (10 + 2m + X) | X | [29], and references therein [35] | |

| Liorhyssus hyalinus | 13 (10A + 2m + X) | AA2 and AA3 | [29], and references therein | |

| Stictopleurus abutilon | 13 (10A + 2m + X) | AА1 | [29], and references therein | |

| Coreidae | ||||

| Coreinae | ||||

| Centrocoris spiniger | 21 (18A + 2m + X) | A1 pair *** | [29], and references therein | |

| Coreus marginatus | 22 (18A + 2m + X1X2) | AA1 | [29], and references therein; [36] | |

| Homoeocerusgraminis | 21 (18A + 2m + X) | AA1 | Absent | |

| Stenocephalidae | ||||

| Dicranocephalus agilis | 13 (10A + 2m + X) | AA1 | [37] | |

| Pentatomoidea | ||||

| Pentatomidae | ||||

| Pentatominae | ||||

| Piezodorus hybneri | 14 (12A + XY) | AA1 and X | [38,39] | |

| Lygaeoidea | ||||

| Lygaeidae | ||||

| Lygaeinae | ||||

| Lygaeus equestris | 14 (12A + XY) | AA (a medium-sized pair) | [29], and references therein | |

| Rhyparochromidae | ||||

| Rhyparochrominae | ||||

| Pterotmetus staphyliniformis | 18 (14A + 2m + XY) | X | [40] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golub, N.V.; Anokhin, B.A.; Grozeva, S.; Kuznetsova, V.G. Comparative Chromosomal Mapping of the 18S rDNA Loci in True Bugs: The First Data for 13 Genera of the Infraorders Cimicomorpha and Pentatomomorpha (Hemiptera, Heteroptera). Genes 2025, 16, 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121516

Golub NV, Anokhin BA, Grozeva S, Kuznetsova VG. Comparative Chromosomal Mapping of the 18S rDNA Loci in True Bugs: The First Data for 13 Genera of the Infraorders Cimicomorpha and Pentatomomorpha (Hemiptera, Heteroptera). Genes. 2025; 16(12):1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121516

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolub, Natalia V., Boris A. Anokhin, Snejana Grozeva, and Valentina G. Kuznetsova. 2025. "Comparative Chromosomal Mapping of the 18S rDNA Loci in True Bugs: The First Data for 13 Genera of the Infraorders Cimicomorpha and Pentatomomorpha (Hemiptera, Heteroptera)" Genes 16, no. 12: 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121516

APA StyleGolub, N. V., Anokhin, B. A., Grozeva, S., & Kuznetsova, V. G. (2025). Comparative Chromosomal Mapping of the 18S rDNA Loci in True Bugs: The First Data for 13 Genera of the Infraorders Cimicomorpha and Pentatomomorpha (Hemiptera, Heteroptera). Genes, 16(12), 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121516