Tracing the Uncharted African Diaspora in Southern Brazil: The Genetic Legacies of Resistance in Two Quilombos from Paraná

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

2.2. Genotyping

2.3. Sanger Sequencing

2.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Maternal Component: Continental Insights into Genetic Ancestry

3.2. Distinct Patterns of Indigenous American Haplogroup Distribution in Feixo and Restinga

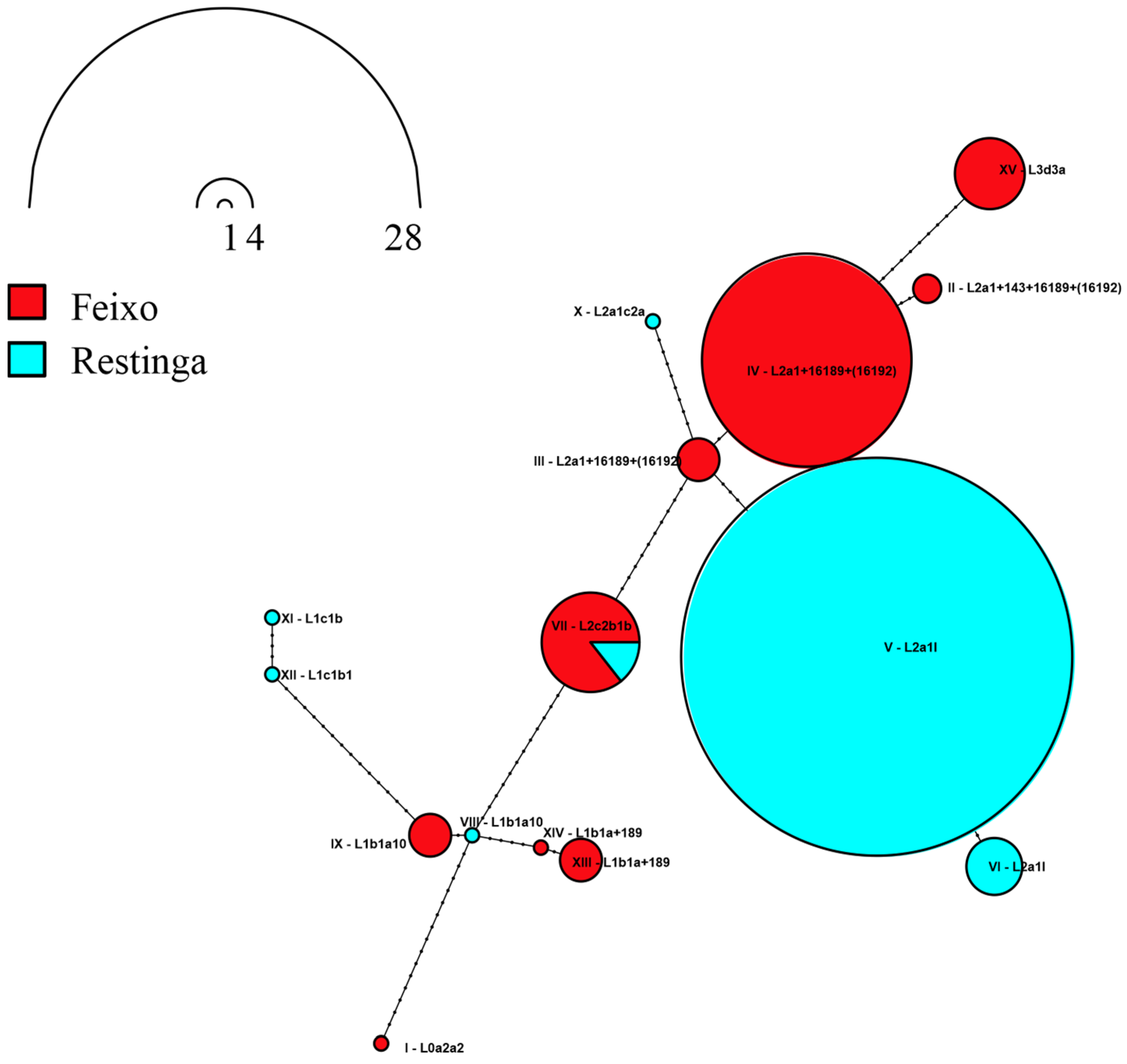

3.3. Feixo and Restinga May Have Received Distinct African Genetic Contributions

3.4. Different Patterns of Sub-Continental Ancestry Are Observed in Both Quilombos

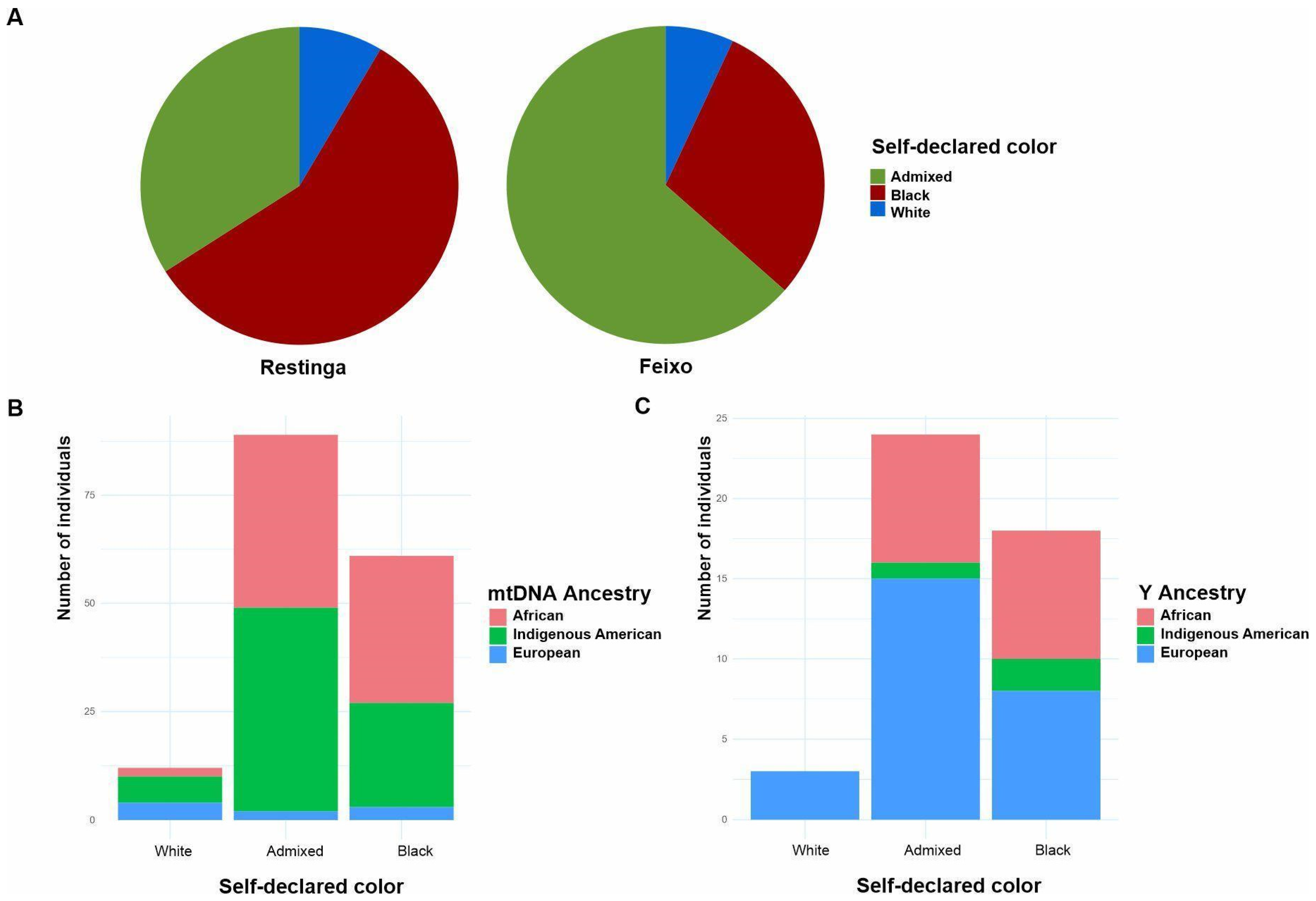

3.5. The Male Lineages in Both Quilombos Were Mainly European

3.6. Molecular Variance (AMOVA) and Diversity Indices of Maternal Lineages in Quilombo Populations

3.7. Maternal but Not Paternal Lineages Reflect Self-Declared “Color”

4. Discussion

4.1. Have Different Indigenous American Ethnic Groups Contributed to the Formation of Feixo and Restinga?

4.2. Differential African Genetic Inputs May Explain the Contrasting Ancestries of Feixo and Restinga

4.3. Paternal Lineages Reveal a Marked Sex Bias in the Formation of Feixo and Restinga

4.4. The African Male Fraction Is Enriched in Eastern/Southern African Haplogroups

4.5. What Self-Declared “Color” Reveals About Genetic Ancestry in Quilombo Communities

5. Conclusions

- Final considerations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CA | Correspondence Analysis |

| Hg | Haplogroup |

| HVR | Mitochondrial hypervariable region |

| InDel | Insertion Deletion |

| MtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| rCRS | Revised Cambridge Reference Sequence |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

References

- Fortes-Lima, C.; Verdu, P. Anthropological Genetics Perspectives on the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, R79–R87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, F.D.S. Mocambos e Quilombos: Uma História Do Campesinato Negro No Brasil, 1st ed.; Claro Enigma: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015; ISBN 978-85-8166-123-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bucciferro, J.R. A Forced Hand: Natives, Africans, and the Population of Brazil, 1545-1850. Rev. Hist. Económica J. Iber. Lat. Am. Econ. Hist. 2013, 31, 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia Estatística (IBGE). Censo Demográfico 2022: Resultados Do Universo; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2022; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, C. Quilombos: Resistência Ao Escravismo, 3rd ed.; Ática: São Paulo, Brazil, 1993; ISBN 8508015584. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, C. História Do Negro Brasileiro, 2nd ed.; Ática: São Paulo, Brazil, 1992; ISBN 85-08-03452-0. [Google Scholar]

- Joerin-Luque, I.A.; Sukow, N.M.; Bucco, I.D.; Tessaro, J.G.; Lopes, C.V.G.; Barbosa, A.A.L.; Beltrame, M.H. Ancestry, Diversity, and Genetics of Health-Related Traits in African-Derived Communities (Quilombos) from Brazil. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggio, A.Z.; Bley, R.B.; Trauczynski, S.C. Abordagem Histórica Sobre a População Negra No Estado de Paraná; Consultoria, F., Ed.; SEJU: Curitiba, Brazil, 2018; Volume 2, ISBN 978-85-66413-14-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas, K.C.S. A Constituição de Identidade Quilombola: Um Olhar Acerca Da Comunidade Quilombola Do Município Da Lapa-PR. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul, Laranjeiras do Sul, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cigolini, A.A.; Da Silva, M. Comunidades Remanescentes Quilombolas: Iconografias e Circulações Na Comunidade Da Restinga—Lapa-Pr, Brasil. Rev. Geogr. 2018, 13, 98–118. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, A.M.; Resende, S.S.; de Sousa, T.N.; de Brito, C.F.A. A Systematic Scoping Review of the Genetic Ancestry of the Brazilian Population. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2019, 42, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, S.; Cunha, L.A.G. Paraná: Desenvolvimento e Diferenças Regionais, 1st ed.; Atena: Ponta Grossa, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, H. Donos de Terras e Escravos No Paraná: Padrões e Hierarquias Nas Primeiras Décadas Do Século XIX. História 2006, 25, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halos, S.C.; Fortuno III, E.S.; Ferreon, A.C.M.; Chu, J.Y.; Miranda, J.; Harada, S.; Benecke, M. Allele Frequency Distributions of the Polymorphic STR Loci HUMVWA, HUMFES, HUMF13A01 and the VNTR D1S80 in a Filipino Population from Metro Manila. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1998, 111, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, W.A.; Bortolini, M.C.; Meyer, D.; Salzano, F.M.; Elion, J.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Schneider, M.P.C.; De Guerra, D.C.; Layrisse, Z.; Castellano, H.M.; et al. Genetic Diversity of Two African and Sixteen South American Populations Determined on the Basis of Six Hypervariable Loci. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1999, 109, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, M.C.; Da Silva, W.A.; De Guerra, D.C.; Remonatto, G.; Mirandola, R.; Hutz, M.H.; Weimer, T.A.; Silva, M.C.B.O.; Zago, M.A.; Salzano, F.M. African-Derived South American Populations: A History of Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Matings According to Sex Revealed by Bi- and Uni-Parental Genetic Markers. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 1999, 11, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.A.; Bortolini, M.C.; Schneider, M.P.C.; Marrero, A.; Elion, J.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Zago, M.A. mtDNA Haplogroup Analysis of Black Brazilian and Sub-Saharan Populations: Implications for the Atlantic Slave Trade. Hum. Biol. 2006, 78, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, B.M.; Bortolini, M.C.; dos Santos, S.E.B.; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, Â.K.C. Mitochondrial DNA Mapping of Social-Biological Interactions in Brazilian Amazonian African-Descendant Populations. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2008, 31, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, L.; Ribeiro-Rodrigues, E.M.; De Mello Auricchio, M.T.B.; Vicente, J.P.; Batista Santos, S.E.; Mingroni-Netto, R.C. Genomic Ancestry of Rural African-Derived Populations from Southeastern Brazil. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2013, 25, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, L.; Nunes, K.; Macedo-Souza, L.I.; Rocha, J.; Meyer, D.; Mingroni-Netto, R.C. Inferring Paternal History of Rural African-Derived Brazilian Populations from Y Chromosomes. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2017, 29, e22930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, L.G.L.; Rodrigues, E.M.; dos Santos, N.P.C.; dos Santos, Â.R.; Guerreiro, J.F.; Santos, S. Afro-Derived Amazonian Populations: Inferring Continental Ancestry and Population Substructure. Hum. Biol. 2011, 83, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, C.C.; Guerra Amorim, C.E.; Godinho, N.M.O.; Toledo, R.C.P.; Nunes, A.; Silva, W.; Da Fonseca Moura, M.M.; De Oliveira, J.C.C.; Pagotto, R.C.; De Nazaré Klautau-Guimarães, M.; et al. Brazilian Quilombos: A Repository of Amerindian Alleles. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2014, 26, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, C.C.; Mendes, F.M.; Santos, C.A.; Klautau-Guimarães, M.d.N.; Lareu, M.V.; Carracedo, Á.; Phillips, C.; Oliveira, S.F. Ancestry Analysis in Rural Brazilian Populations of African Descent. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 36, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Dos-Santos, Â.K.C.; Pereira, J.M.; Lobato, M.R.F.; Carvalho, B.M.; Guerreiro, J.F.; Batista Dos Santos, S.E. Dissimilarities in the Process of Formation of Curiaú, a Semi-Isolated Afro-Brazilian Population of the Amazon Region. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2002, 14, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe-Sandes, K.; Silva, W.A.; Zago, M.A. Heterogeneity of the Y Chromosome in Afro-Brazilian Populations. Hum. Biol. 2004, 76, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daflon, V.T.; Carvalhaes, F.; Feres Júnior, J. Sentindo Na Pele: Percepções de Discriminação Cotidiana de Pretos e Pardos No Brasil. Dados 2017, 60, 293–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, M.E. Afinidades Filogeográficas y Estructuración Geográfica de los Linajes Maternos y Paternos Presentes en Poblaciones Humanas del Noroeste Argentino. PhD Thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, L.S.J.; Muzzio, M.; Schwab, M.; Costantino, M.L.B.; Barreto, G.; Bailliet, G. Human Y-Chromosome SNP Characterization by Multiplex Amplified Product-Length Polymorphism Analysis. Electrophoresis 2014, 35, 2524–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Moreira, M.L.; Montenegro, Y.H.A.; Salatino-Oliveira, A.; Montano, H.Q.; Bareiro, R.F.N.; dos Santos-Lopes, S.S.; da Silva, T.R.; Azevedo, L.K.S.; da Silva, K.B.L.; Moreira, A.W. de A.; et al. Comprehensive Characterization of a Cluster of Mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB in Ecuador. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Bankier, A.T.; Barrell, B.G.; de Bruijn, M.H.L.; Coulson, A.R.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I.C.; Nierlich, D.P.; Roe, B.A.; Sanger, F.; et al. Sequence and Organization of the Human Mitochondrial Genome. Nature 1981, 290, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.M.; Kubacka, I.; Chinnery, P.F.; Lightowlers, R.N.; Turnbull, D.M.; Howell, N. Reanalysis and Revision of the Cambridge Reference Sequence for Human Mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönherr, S.; Weissensteiner, H.; Kronenberg, F.; Forer, L. Haplogrep 3—An Interactive Haplogroup Classification and Analysis Platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, W263–W268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Macaulay, V.; Torroni, A.; Scozzari, R.; Prata, M.J.; Amorim, A. Prehistoric and Historic Traces in the mtDNA of Mozambique: Insights into the Bantu Expansions and the Slave Trade. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2001, 65, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.M. Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links; The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-8078-2973-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pierron, D.; Heiske, M.; Razafindrazaka, H.; Rakoto, I.; Rabetokotany, N.; Ravololomanga, B.; Rakotozafy, L.M.A.; Rakotomalala, M.M.; Razafiarivony, M.; Rasoarifetra, B.; et al. Genomic Landscape of Human Diversity across Madagascar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6498–E6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis, E. Pegas: An R Package for Population Genetics with an Integrated-Modular Approach. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamvar, Z.N.; Tabima, J.F.; Grünwald, N.J. Poppr: An R Package for Genetic Analysis of Populations with Clonal, Partially Clonal, and/or Sexual Reproduction. PeerJ 2014, 2, e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Iglesias, V.; Jaime, J.C.; Carracedo, Á.; Salas, A. Coding Region Mitochondrial DNA SNPs: Targeting East Asian and Native American Haplogroups. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2007, 1, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, J.M.B.; Schwab, M.E.; Beltramo, J.; Jurado-Medina, L.S.; Muzzio, M.; Ramallo, V.; Bailliet, G.; Bravi, C.M. Diferenciación Regional de Poblaciones Nativas de América a Partir Del Análisis de Los Linajes Maternos. Intersecc. En Antropol. 2017, 18, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Underhill, P.A.; Kivisild, T. Use of Y Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Population Structure in Tracing Human Migrations. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2007, 41, 539–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphalen, C.M. A Introdução de Escravos Novos No Litoral Paranaense. Rev. De História 1972, 44, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltis, D.; Richardson, D. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. 2010.

- Batini, C.; Coia, V.; Battaggia, C.; Rocha, J.; Pilkington, M.M.; Spedini, G.; Comas, D.; Destro-Bisol, G.; Calafell, F. Phylogeography of the Human Mitochondrial L1c Haplogroup: Genetic Signatures of the Prehistory of Central Africa. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 43, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Fehn, A.M.; Aço, T.; Lages, F.; Gayà-Vidal, M.; Pakendorf, B.; Stoneking, M.; Rocha, J. Matriclans Shape Populations: Insights from the Angolan Namib Desert into the Maternal Genetic History of Southern Africa. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2018, 165, 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelt, H.J.; Macaulay, V.; Richards, M. Human Mitochondrial DNA and the Evolution of Homo Sapiens, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, 2006; ISBN 978-0-333-22779-4. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, P.; Ermini, L.; Thomson, N.; Mormina, M.; Rito, T.; Röhl, A.; Salas, A.; Oppenheimer, S.; Macaulay, V.; Richards, M.B. Correcting for Purifying Selection: An Improved Human Mitochondrial Molecular Clock. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 84, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Alshamali, F.; Silva, P.; Carrilho, C.; Mandlate, F.; Jesus Trovoada, M.; Černý, V.; Pereira, L.; Soares, P. 60,000 Years of Interactions between Central and Eastern Africa Documented by Major African Mitochondrial Haplogroup L2. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, D. O Povo Brasileiro: A Formação e o Sentido Do Brasil; Companhia das Letras: São Paulo, Brazil, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-López, B.; Granizo-Rodríguez, E.; Palencia-Madrid, L.; Raffone, C.; Baeta, M.; de Pancorbo, M.M. Phylogeographic Review of Y Chromosome Haplogroups in Europe. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grugni, V.; Raveane, A.; Ongaro, L.; Battaglia, V.; Trombetta, B.; Colombo, G.; Capodiferro, M.R.; Olivieri, A.; Achilli, A.; Perego, U.A.; et al. Analysis of the Human Y-Chromosome Haplogroup Q Characterizes Ancient Population Movements in Eurasia and the Americas. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailliet, G.; Ramallo, V.; Muzzio, M.; García, A.; Santos, M.R.; Alfaro, E.L.; Dipierri, J.E.; Salceda, S.; Carnese, F.R.; Bravi, C.M.; et al. Brief Communication: Restricted Geographic Distribution for Y-Q* Paragroup in South America. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2009, 140, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletto, M.M.; Malaghini, M.; Silva, J.S.; Bicalho, M.G.; Braun-Prado, K. Mitochondrial DNA Control Region Diversity in a Population from Parana State—Increasing the Brazilian Forensic Database. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2019, 133, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joerin-Luque, I.A.; Augusto, D.G.; Calonga-Solís, V.; de Almeida, R.C.; Lopes, C.V.G.; Petzl-Erler, M.L.; Beltrame, M.H. Uniparental Markers Reveal New Insights on Subcontinental Ancestry and Sex-Biased Admixture in Brazil. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2022, 297, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, A.R.; Silva-Junior, W.A.; Bravi, C.M.; Hutz, M.H.; Petzl-Erler, M.L.; Ruiz-Linares, A.; Salzano, F.M.; Bortolini, M.C. Demographic and Evolutionary Trajectories of the Guarani and Kaingang Natives of Brazil. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2007, 132, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisso-Machado, R.; Cátira Bortolini, M.; Salzano, F.M. Uniparental Genetic Markers in South Amerindians. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2012, 35, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, G.M.; Reales, G.; Bortolini, M.C.; Fagundes, N.J.R. Measuring the Impact of European Colonization on Native American Populations in Southern Brazil and Uruguay: Evidence from mtDNA. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2019, 31, e23243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.; Brehm, A. African Human mtDNA Phylogeography At-a-Glance. J. Anthropol. Sci. 2011, 89, 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana-Murci, L.; Quach, H.; Harmant, C.; Luca, F.; Massonnet, B.; Patin, E.; Sica, L.; Mouguiama-Daouda, P.; Comas, D.; Tzur, S.; et al. Maternal Traces of Deep Common Ancestry and Asymmetric Gene Flow between Pygmy Hunter-Gatherers and Bantu-Speaking Farmers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1596–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oven, M. PhyloTree Build 17: Growing the Human Mitochondrial DNA Tree. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2015, 5, e392–e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Vicente, M.; Oliveira, S.; Bostoen, K.; Rocha, J.; Stoneking, M.; Pakendorf, B. Migration and Interaction in a Contact Zone: mtDNA Variation among Bantu-Speakers in Southern Africa. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, A.; Richards, M.; Lareu, M.-V.; Scozzari, R.; Coppa, A.; Torroni, A.; Macaulay, V.; Carracedo, Á. The African Diaspora: Mitochondrial DNA and the Atlantic Slave Trade. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemes, R.B.; Nunes, K.; Meyer, D.; Mingroni-Netto, R.C.; Otto, P.A. Estimation of Inbreeding and Substructure Levels in African-Derived Brazilian Quilombo Populations. Hum. Biol. 2014, 86, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, R. Notices of Brazil in 1828 and 1829 Volume I; Frederick Westley and A.H Davis: London, UK, 1830. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, A. O Genocidio Do Negro Brasileiro: Processo de Um Racismo Mascarado, 2nd ed.; Perspectiva: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aidoo, L. Slavery Unseen: Sex, Power, and Violence in Brazilian History; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2018; Volume 47, ISBN 978-0-8223-7168-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, K.; Castro e Silva, M.A.; Rodrigues, M.R.; Lemes, R.B.; Pezo-Valderrama, P.; Kimura, L.; de Sena, L.S.; Krieger, J.E.; Varela, M.C.; de Azevedo, L.O.; et al. Admixture’s Impact on Brazilian Population Evolution and Health. Science 2025, 388, eadl3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Atanasio, E.; Trionfetti, F.; Bonito, M.; Sellitto, D.; Coppa, A.; Berti, A.; Trombetta, B.; Cruciani, F.; D’Atanasio, E.; Trionfetti, F.; et al. Y Haplogroup Diversity of the Dominican Republic: Reconstructing the Effect of the European Colonization and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trades. Genome Biol. Evol. 2020, 12, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, B.; Simão, F.; Gomes, V.; Nguidi, M.; Amorim, A.; Carvalho, E.F.; Marrugo, J.; Gusmão, L. Searching for the Roots of the First Free African American Community. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.Y. Women, Race, and Class; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1944; ISBN 978-0-307-79849-7. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, M.; Sequeira, F.; Luiselli, D.; Beleza, S.; Rocha, J. On the Edge of Bantu Expansions: mtDNA, Y Chromosome and Lactase Persistence Genetic Variation in Southwestern Angola. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobling, M.A.; Tyler-Smith, C. Human Y-Chromosome Variation in the Genome-Sequencing Era. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombetta, B.; D’Atanasio, E.; Massaia, A.; Ippoliti, M.; Coppa, A.; Candilio, F.; Coia, V.; Russo, G.; Dugoujon, J.-M.; Moral, P.; et al. Phylogeographic Refinement and Large Scale Genotyping of Human Y Chromosome Haplogroup E Provide New Insights into the Dispersal of Early Pastoralists in the African Continent. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruciani, F.; La Fratta, R.; Santolamazza, P.; Sellitto, D.; Pascone, R.; Moral, P.; Watson, E.; Guida, V.; Colomb, E.B.; Zaharova, B.; et al. Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowold, D.; Garcia-Bertrand, R.; Calderon, S.; Rivera, L.; Benedico, D.P.; Alfonso Sanchez, M.A.; Chennakrishnaiah, S.; Varela, M.; Herrera, R.J. At the Southeast Fringe of the Bantu Expansion: Genetic Diversity and Phylogenetic Relationships to Other Sub-Saharan Tribes. Meta Gene 2014, 2, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Filippo, C.; Barbieri, C.; Whitten, M.; Mpoloka, S.W.; Gunnarsdóttir, E.D.; Bostoen, K.; Nyambe, T.; Beyer, K.; Schreiber, H.; De Knijff, P.; et al. Y-Chromosomal Variation in Sub-Saharan Africa: Insights into the History of Niger-Congo Groups. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, M.H.; Borda, V.; Leal, T.P.; Moreira, R.G.; Bergen, A.W.; Kehdy, F.S.G.; Alvim, I.; Aquino, M.M.; Araujo, G.S.; Araujo, N.M.; et al. Origins, Admixture Dynamics, and Homogenization of the African Gene Pool in the Americas. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, B.M.; Gignoux, C.; Lin, A.A.; Oefner, P.J.; Shen, P.; Scozzari, R.; Cruciani, F.; Tishkoff, S.A.; Mountain, J.L.; Underhill, P.A. Y-Chromosomal Evidence of a Pastoralist Migration through Tanzania to Southern Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10693–10698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, M.; Wade, P. Genetics against Race: Science, Politics and Affirmative Action in Brazil. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2015, 45, 816–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Linares, A.; Adhikari, K.; Acuña-Alonzo, V.; Quinto-Sanchez, M.; Jaramillo, C.; Arias, W.; Fuentes, M.; Pizarro, M.; Everardo, P.; de Avila, F.; et al. Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima-Costa, M.F.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Barreto, M.L.; Gouveia, M.; Horta, B.L.; Mambrini, J.; Kehdy, F.S.G.; Pereira, A.; Rodrigues-Soares, F.; Victora, C.G.; et al. Genomic Ancestry and Ethnoracial Self-Classification Based on 5,871 Community-Dwelling Brazilians (The Epigen Initiative). Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardena, M.M.S.G.S.G.; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, Â.; Santos, S.; Mansur, A.J.; Pereira, A.C.; Fridman, C. Assessment of the Relationship between Self-Declared Ethnicity, Mitochondrial Haplogroups and Genomic Ancestry in Brazilian Individuals. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resque, R.; Gusmão, L.; Geppert, M.; Roewer, L.; Palha, T.; Alvarez, L.; Ribeiro-Dos-santos, Â.; Santos, S. Male Lineages in Brazil: Intercontinental Admixture and Stratification of the European Background. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaan, A.P.; Gusmaõ, L.; Jannuzzi, J.; Modesto, A.; Amador, M.; Marques, D.; Rabenhorst, S.H.; Montenegro, R.; Lopes, T.; Yoshioka, F.K.; et al. New Insights on Intercontinental Origins of Paternal Lineages in Northeast Brazil. BMC Evol. Biol. 2020, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, A.; Richards, M.; De la Fe, T.; Lareu, M.-V.; Sobrino, B.; Sánchez-Diz, P.; Macaulay, V.; Carracedo, Á. The Making of the African mtDNA Landscape. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 71, 1082–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Whitten, M.; Beyer, K.; Schreiber, H.; Li, M.; Pakendorf, B. Contrasting Maternal and Paternal Histories in the Linguistic Context of Burkina Faso. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.L.; Soares, P.; Dugoujon, J.M.; Novelletto, A.; Rodríguez, J.N.; Rito, T.; Oliveira, M.; Melhaoui, M.; Baali, A.; Pereira, L.; et al. Early Holocenic and Historic mtDNA African Signatures in the Iberian Peninsula: The Andalusian Region as a Paradigm. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Butthof, A.; Bostoen, K.; Pakendorf, B. Genetic Perspectives on the Origin of Clicks in Bantu Languages from Southwestern Zambia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippold, S.; Xu, H.; Ko, A.; Li, M.; Renaud, G.; Butthof, A.; Schröder, R.; Stoneking, M. Human Paternal and Maternal Demographic Histories: Insights from High-Resolution Y Chromosome and mtDNA Sequences. Investig. Genet. 2014, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Güldemann, T.; Naumann, C.; Gerlach, L.; Berthold, F.; Nakagawa, H.; Mpoloka, S.W.; Stoneking, M.; Pakendorf, B. Unraveling the Complex Maternal History of Southern African Khoisan Populations. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 2014, 153, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batini, C.; Lopes, J.; Behar, D.M.; Calafell, F.; Jorde, L.B.; van der Veen, L.; Quintana-Murci, L.; Spedini, G.; Destro-Bisol, G.; Comas, D. Insights into the Demographic History of African Pygmies from Complete Mitochondrial Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behar, D.M.; Villems, R.; Soodyall, H.; Blue-Smith, J.; Pereira, L.; Metspalu, E.; Scozzari, R.; Makkan, H.; Tzur, S.; Comas, D.; et al. The Dawn of Human Matrilineal Diversity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, V.M.; Marrero, P.; Abu-Amero, K.K.; Larruga, J.M. Carriers of Mitochondrial DNA Macrohaplogroup L3 Basal Lineages Migrated Back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 Years Ago. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2018, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.D.; Cherni, L.; Fernandes, V.; Freitas, F.; Ammar el Gaaied, A.B.; Pereira, L. Data from Complete mtDNA Sequencing of Tunisian Centenarians: Testing Haplogroup Association and the “Golden Mean” to Longevity. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2009, 130, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Walt, E.M.; Smuts, I.; Taylor, R.W.; Elson, J.L.; Turnbull, D.M.; Louw, R.; van der Westhuizen, F.H. Characterization of mtDNA Variation in a Cohort of South African Paediatric Patients with Mitochondrial Disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 20, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, L.; Almeida, M.; Azonbakin, S.; Matos, E.; Franco-duarte, R.; Alberto, G.; Salas, A.; Rosa, A.; Richards, M.B.; Soares, P.; et al. Phylogeography of Sub-Saharan Mitochondrial Lineages Outside Africa Highlights the Roles of the Holocene Climate Changes and the Atlantic Slave Trade. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Haplogroup | Quilombos | Feixo | Restinga | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mtDNA | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| A | 16 | 9.9 | 12 | 10.4 | 4 | 8.5 |

| B | 6 | 3.7 | 5 | 4.3 | 1 | 2.1 |

| C | 55 | 34.0 | 53 | 46.1 | 2 | 4.3 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Indigenous American | 77 | 47.5 | 70 | 60.9 | 7 | 14.9 |

| M | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 |

| N | 8 | 4.9 | 5 | 4.3 | 3 | 6.4 |

| Total European | 9 | 5.6 | 6 | 5.2 | 3 | 6.4 |

| L | 76 | 46.9 | 39 | 33.9 | 37 | 78.7 |

| L0a2a2 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 |

| L1b1a+189 | 4 | 2.5 | 4 | 3.5 | 0 | 0 |

| L1b1a10 | 4 | 2.5 | 3 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.1 |

| L1c1b | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.1 |

| L1c1b1 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.1 |

| L2a1+143+16189+(16192) | 2 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 |

| L2a1+16189+(16192) | 18 | 11.1 | 18 | 15.7 | 0 | 0 |

| L2a1c2a | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.1 |

| L2a1l | 32 | 19.8 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 68.1 |

| L2c2b1b | 7 | 4.3 | 6 | 5.2 | 1 | 2.1 |

| L3d3a | 5 | 3.1 | 5 | 4.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Total African | 76 | 46.9 | 39 | 33.9 | 37 | 78.7 |

| Y chromosome | ||||||

| Q | 3 | 6.7 | 3 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Q-M3 | 3 | 6.7 | 3 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Indigenous American | 3 | 6.7 | 3 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 |

| R | 19 | 42.2 | 13 | 39.4 | 6 | 50.0 |

| F | 7 | 15.6 | 4 | 12.1 | 3 | 25.0 |

| Total European | 26 | 57.8 | 17 | 51.5 | 9 | 75.0 |

| E | 16 | 35.6 | 13 | 39.4 | 3 | 25.0 |

| E-M35 | 8 | 17.8 | 6 | 18.2 | 2 | 16.7 |

| E-M2 | 3 | 6.7 | 2 | 6.1 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Total African | 16 | 35.6 | 13 | 39.4 | 3 | 25.0 |

| Population | N | NHg | Nhap | Nhap/N | H | Variance | π | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quilombos | 76 | 16 | 16 | 0.211 | - | - | - | - |

| Feixo | 39 | 7 | 10 | 0.256 | 0.812 | 0.002 | 0.131 | 0.005 |

| Restinga | 37 | 6 | 6 | 0.162 | 0.390 | 0.010 | 0.049 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joerin-Luque, I.A.; Baldon Blaczyk, I.; Ianzen dos Santos, P.; Guimarães Alves, A.C.; Sukow, N.M.; Malanczyn de Oliveira, A.C.; Farias de Cristo, T.; Rodrigues do Amaral Bispo, A.; Gros, A.F.; Santos Saatkamp, M.L.; et al. Tracing the Uncharted African Diaspora in Southern Brazil: The Genetic Legacies of Resistance in Two Quilombos from Paraná. Genes 2025, 16, 1510. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121510

Joerin-Luque IA, Baldon Blaczyk I, Ianzen dos Santos P, Guimarães Alves AC, Sukow NM, Malanczyn de Oliveira AC, Farias de Cristo T, Rodrigues do Amaral Bispo A, Gros AF, Santos Saatkamp ML, et al. Tracing the Uncharted African Diaspora in Southern Brazil: The Genetic Legacies of Resistance in Two Quilombos from Paraná. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1510. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121510

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoerin-Luque, Iriel A., Isadora Baldon Blaczyk, Priscila Ianzen dos Santos, Ana Cecília Guimarães Alves, Natalie Mary Sukow, Ana Carolina Malanczyn de Oliveira, Thomas Farias de Cristo, Angela Rodrigues do Amaral Bispo, Aymee Fernanda Gros, Maria Letícia Santos Saatkamp, and et al. 2025. "Tracing the Uncharted African Diaspora in Southern Brazil: The Genetic Legacies of Resistance in Two Quilombos from Paraná" Genes 16, no. 12: 1510. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121510

APA StyleJoerin-Luque, I. A., Baldon Blaczyk, I., Ianzen dos Santos, P., Guimarães Alves, A. C., Sukow, N. M., Malanczyn de Oliveira, A. C., Farias de Cristo, T., Rodrigues do Amaral Bispo, A., Gros, A. F., Santos Saatkamp, M. L., Dobis Barros, V., Gehlen Tessaro, J., da Silveira Costa, M. E., Leonardo Garcia, L., Dall Oglio Bucco, I., de Moura Bones, D. R., Cupertino, S. E., Boslooper Gonçalves, L., Leandro Martins, A., ... Beltrame, M. H. (2025). Tracing the Uncharted African Diaspora in Southern Brazil: The Genetic Legacies of Resistance in Two Quilombos from Paraná. Genes, 16(12), 1510. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121510