Matrix Metalloproteinase Polymorphisms as Genetic Risk Factors for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Football Players: A Case–Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Ethics Committee

2.3. Genetic Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Single-Locus Analysis—Case Group

3.2. Association of MMP1 rs1799750, MMP10 rs486055, and MMP12 rs2276109 with ACLF, ACLS, ACLRP, and ACLRC

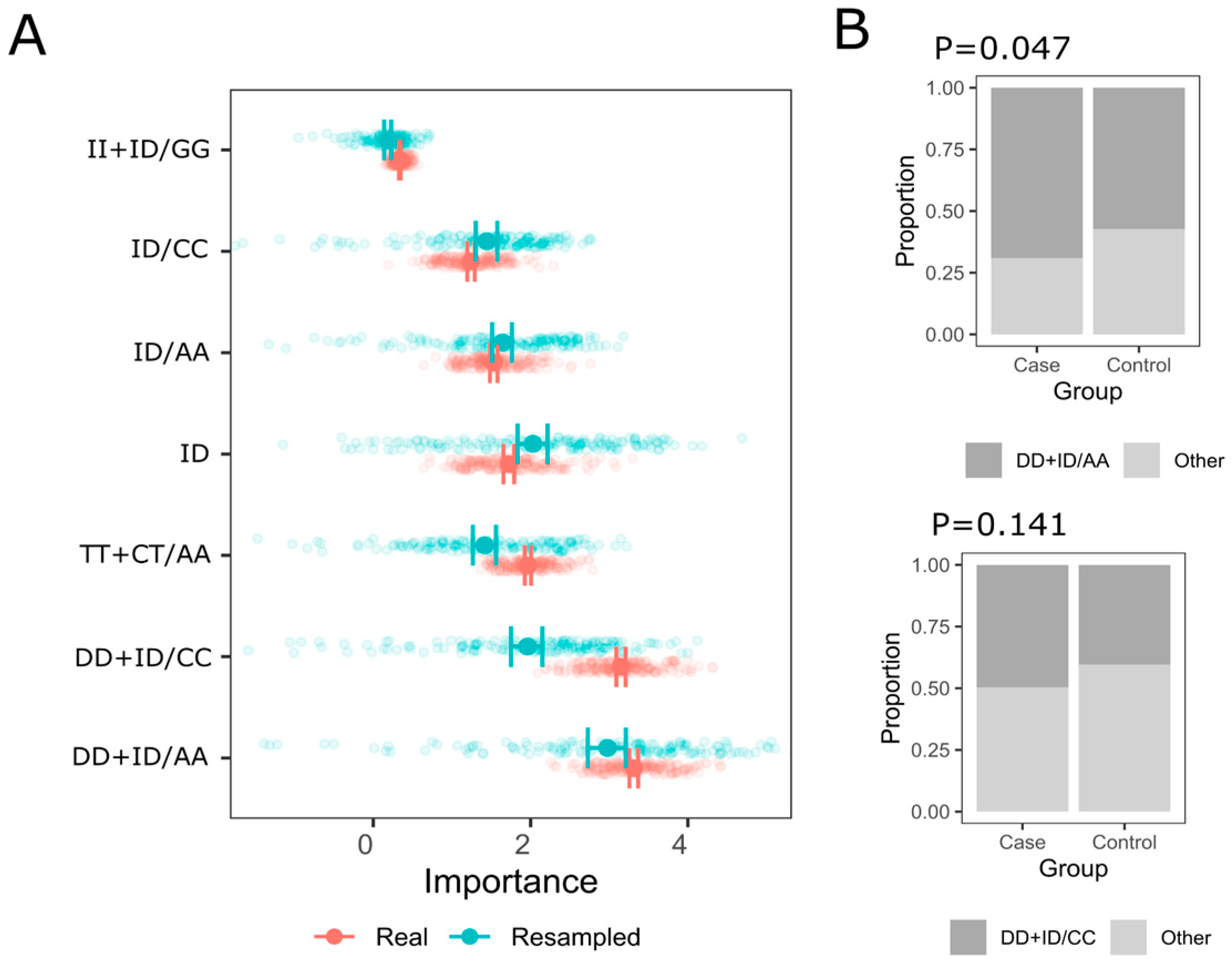

3.3. Multi-Locus Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. MMP1 rs1799750

4.2. MMP10 rs486055

4.3. MMP12 rs2276109

4.4. Biological Mechanisms and Functional Implications

4.5. Comparative Insights with Other Soft Tissue Injuries

4.6. Environmental and Biomechanical Interactions

4.7. Epigenetics and Gene Regulation

4.8. Clinical and Translational Implications

4.9. Methodological Considerations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gwiazdon, P.; Racut, A.; Strozik, M.; Bala, W.; Klimek, K.; Rajca, J.; Hajduk, G. Diagnosis, treatment and statistic of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2019, 11, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Bojarczuk, A.; Cieszczyk, P. The COL27A1 and COL11A1 gene variants are not associated with the susceptibility to anterior cruciate ligament rupture in Polish athletes. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2023, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbans, W.J.; September, A.V.; Collins, M. Tendon and Ligament Genetics: How Do They Contribute to Disease and Injury? A Narrative Review. Life 2022, 12, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davis, M.E.; Gumucio, J.P.; Sugg, K.B.; Bedi, A.; Mendias, C.L. MMP inhibition as a potential method to augment the healing of skeletal muscle and tendon extracellular matrix. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 115, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yadav, P.K.; Ghosh, M.; Kataria, M. Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) in Cancer Immunotherapy. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects; Chakraborti, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Buono, A.; Oliva, F.; Osti, L.; Maffulli, N. Metalloproteases and tendinopathy. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013, 21, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maes, H.H.M.; Beunen, G.P.; Vlietinck, R.F.; Neale, M.C.; Thomis, M.; VandenEynde, B.; Lysens, R.; Simons, J.; Derom, C.; Derom, R. Inheritance of physical fitness in 10-yr-old twins and their parents. Med. Sci. Sports Exer. 1996, 28, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battie, M.C.; Levalahti, E.; Videman, T.; Burton, K.; Kaprio, J. Heritability of lumbar flexibility and the role of disc degeneration and body weight. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, K.; Turkiewicz, A.; Hughes, V.; Frobell, R.; Englund, M. High genetic contribution to anterior cruciate ligament rupture: Heritability ~69. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 55, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, Y.; Anderton, R.S.; Cochrane Wilkie, J.L.; Rogalski, B.; Laws, S.M.; Jones, A.; Spiteri, T.; Hince, D.; Hart, N.H. Genetic Variants within NOGGIN, COL1A1, COL5A1, and IGF2 are Associated with Musculoskeletal Injuries in Elite Male Australian Football League Players: A Preliminary Study. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzemska, B.; Cięszczyk, P.; Żekanowski, C. The Genetic Basis of Non-Contact Soft Tissue Injuries-Are There Practical Applications of Genetic Knowledge? Cells 2024, 13, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malila, S.; Yuktanandana, P.; Saowaprut, S.; Jiamjarasrangsi, W.; Honsawek, S. Association between matrix metalloproteinase-3 polymorphism and anterior cruciate ligament ruptures. Genet. Mol. Res. 2011, 10, 4158–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, M.; Raleigh, S.M. Genetic risk factors for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries. Med. Sport. Sci. 2009, 54, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbon, A.; Hobbs, H.; van der Merwe, W.; Raleigh, S.M.; Cook, J.; Handley, C.J.; Posthumus, M.; Collins, M.; September, A.V. The MMP3 gene in musculoskeletal soft tissue injury risk profiling: A study in two independent sample groups. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 35, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.; Xu, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhao, H. The association between MMP-1 gene rs1799750 polymorphism and knee osteoarthritis risk. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20181257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, L.M.; Schistad, E.I.; Storesund, A.; Pedersen, L.M.; Espeland, A.; Rygh, L.J.; Røe, C.; Gjerstad, J. The MMP1 rs1799750 2G Allele is Associated With Increased Low Back Pain, Sciatica, and Disability After Lumbar Disk Herniation. Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, M.C.; De Wet, H.; Collins, M. Matrix metalloproteinase genes on chromosome 11q22 and risk of carpal tunnel syndrome. Rheumatol. Int. 2016, 36, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthumus, M.; Collins, M.; van der Merwe, L.; O’Cuinneagain, D.; van der Merwe, W.; Ribbans, W.J.; Schwellnus, M.P.; Raleigh, S.M. Matrix metalloproteinase genes on chromosome 11q22 and the risk of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2012, 22, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeuwisse, W.H.; Tyreman, H.; Hagel, B.; Emery, C. A dynamic model of etiology in sport injury: The recursive nature of risk and causation. Clin. J. Sport. Med. 2007, 17, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, H.; Haimour, A.; Toor, R.; Fernandez-Patron, C. The Emerging Role of Epigenetic Mechanisms in the Causation of Aberrant MMP Activity during Human Pathologies and the Use of Medicinal Drugs. Biomolecules. 2021, 11, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chernov, A.V.; Strongin, A.Y. Epigenetic regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and their collagen substrates in cancer. Biomol. Concepts 2011, 2, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Chi, Q.; Yang, L.; Paul Sung, K.L.; Wang, C. Effect of mechanical injury and IL-1β on the expression of LOXs and MMP-1, 2, 3 in PCL fibroblasts after co-culture with synoviocytes. Gene 2021, 766, 145149, ISSN 0378-1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Yang, L.; Xue, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P.C.; Sung, K.P. Differential expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament fibroblasts after a mechanical injury: Involvement of the p65 subunit of NF-κB. Wound Repair. Regen. 2009, 17, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, S.; Smith, L.; Fields, G.F. Matrix metalloproteinase collagenolysis in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 1940–1951, ISSN 0167-4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, L.G.N.; Thode, H.; Eslambolchi, Y.; Chopra, S.; Young, D.; Gill, S.; Devel, L.; Dufour, A. Matrix Metalloproteinases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2022, 74, 712–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Kim, W.J. The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase in Inflammation with a Focus on Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parks, W.; Wilson, C.; López-Boado, Y. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, M.; Nijman, F.; van Meurs, J.; Reijman, M.; Meuffels, D.E. Genetic Variants and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1637–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, D.; Bope, C.D.; Patricios, J.; Chimusa, E.R.; Collins, M.; September, A.V. A whole genome sequencing approach to anterior cruciate ligament rupture—A twin study in two unrelated families. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, V.; Longo, U.G.; Berton, A.; Salvatore, G.; Forriol, F.; de Sire, A.; Denaro, V. Genome-Wide Association Screens for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Buono, A.; Oliva, F.; Longo, U.G.; Rodeo, S.A.; Orchard, J.; Denaro, V.; Maffulli, N. Metalloproteases and rotator cuff disease. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2012, 21, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, R.; Cesari, E.; Vinci, E.; Castagna, A. Role of metalloproteinases in rotator cuff tear. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2011, 19, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karousou, E.; Ronga, M.; Vigetti, D.; Passi, A.; Maffulli, N. Collagens, proteoglycans, MMP-2, MMP-9 and TIMPs in human achilles tendon rupture. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 1577–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, S.; Carr, A.J. Lessons we can learn from gene expression patterns in rotator cuff tears and tendinopathies. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2012, 21, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, G. The pathogenesis of tendinopathy. A molecular perspective. Rheumatology 2004, 43, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briški, N.; Vrgoč, G.; Knjaz, D.; Janković, S.; Ivković, A.; Pećina, M.; Lauc, G. Association of the matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP3) single nucleotide polymorphisms with tendinopathies: Case-control study in high-level athletes. Int. Orthop. 2021, 45, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigetti, D.; Viola, M.; Karousou, E.; Deleonibus, S.; Karamanou, K.; De Luca, G.; Passi, A. Epigenetics in extracellular matrix remodeling and hyaluronan metabolism. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 4980–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, D.E.; Alonso, D.F.; Yoshiji, H.; Thorgeirsson, U.P. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: Structure, regulation and biological functions. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 74, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gumucio, J.P.; Sugg, K.B.; Mendias, C.L. TGF-β Superfamily Signaling in Muscle and Tendon Adaptation to Resistance Exercise. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2015, 43, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Khoury, M.J. Implications of small effect sizes of individual genetic variants on the design and interpretation of genetic association studies of complex diseases. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 164, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, S.; Saunders, C.; Cieszczyk, P.; Ficek, K.; Häger, C.K.; Stattin, E.L.; September, A.V. A novel combination of genomic loci in ITGB2, COL5A1 and VEGFA associated with anterior cruciate ligament rupture susceptibility: Insights from Australian, Polish, Swedish, and South African cohorts. Biol. Sport. 2026, 43, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, N.F.N.; Meeuwisse, W.H.; Mendonça, L.D.; Nettel-Aguirre, A.; Ocarino, J.M.; Fonseca, S.T. Complex systems approach for sports injuries: Moving from risk factor identification to injury pattern recognition—Narrative review and new concept. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Controls, N = 136 1 | Cases, N = 160 1 | p 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27 (4) | 36 (7) | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 178 (7) | 178 (6) | 0.284 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | |

| Body mass (kg) | 73 (16) | 78 (10) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Model | Cases N (%) | Controls N (%) | OR (95% CI) | P/FDR P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codominant | 0.018/0.072 | |||||||

| D/D | 34 (25.0) | 48 (30.4) | 1.00 | |||||

| I/D | 57 (41.9) | 80 (50.6) | 1.70 (0.80; 3.62) | |||||

| I/I | 45 (33.1) | 30 (19.0) | 0.59 (0.26; 1.35) | |||||

| Dominant | 0.728/0.728 | |||||||

| D/D | 34 (25.0) | 48 (30.4) | 1.00 | |||||

| I/D-I/I | 102 (75.0) | 110 (69.6) | 1.13 (0.57; 2.23) | |||||

| Recessive | 0.014/0.072 | |||||||

| D/D-I/D | 91 (66.9) | 128 (81.0) | 1.00 | |||||

| I/I | 45 (33.1) | 30 (19.0) | 0.42 (0.21; 0.85) | |||||

| Overdominant | 0.011/0.072 | |||||||

| D/D-I/I | 79 (58.1) | 78 (49.4) | 1.00 | |||||

| I/D | 57 (41.9) | 80 (50.6) | 2.23 (1.18; 4.19) | |||||

| Model | Cases N (%) | Controls N (%) | OR (95% CI) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codominant | 0.674/0.728 | |||||||

| C/C | 98 (72.1) | 103 (64.8) | 1.00 | |||||

| C/T | 35 (25.7) | 50 (31.4) | 1.21 (0.61; 2.41) | |||||

| T/T | 3 (2.2) | 6 (3.8) | 0.54 (0.08; 3.55) | |||||

| Dominant | 0.718/0.728 | |||||||

| C/C | 98 (72.1) | 103 (64.8) | 1.00 | |||||

| C/T-T/T | 38 (27.9) | 56 (35.2) | 1.13 (0.58; 2.19) | |||||

| Recessive | 0.486/0.716 | |||||||

| C/C-C/T | 133 (97.8) | 153 (96.2) | 1.00 | |||||

| T/T | 3 (2.2) | 6 (3.8) | 0.51 (0.08; 3.33) | |||||

| Overdominant | 0.537/0.716 | |||||||

| C/C-T/T | 101 (74.3) | 109 (68.6) | 1.00 | |||||

| C/T | 35 (25.7) | 50 (31.4) | 1.24 (0.63; 2.45) | |||||

| Model | Cases N (%) | Controls N (%) | OR (95% CI) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codominant | 0.209/0.418 | |||||||

| A/A | 106 (77.9) | 128 (80.5) | 1.00 | |||||

| A/G | 30 (22.1) | 27 (17.0) | 1.50 (0.70; 3.20) | |||||

| G/G | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.5) | 0.00 | |||||

| Dominant | 0.206/0.418 | |||||||

| A/A | 106 (77.9) | 128 (80.5) | 1.00 | |||||

| A/G-G/G | 30 (22.1) | 31 (19.5) | 1.62 (0.77; 3.41) | |||||

| Recessive | 0.152/0.418 | |||||||

| A/A-A/G | 136 (100.0) | 155 (97.5) | 1.00 | |||||

| G/G | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.5) | 0.00 | |||||

| Overdominant | 0.324/0.555 | |||||||

| A/A-G/G | 106 (77.9) | 132 (83.0) | 1.00 | |||||

| A/G | 30 (22.1) | 27 (17.0) | 1.46 (0.68; 3.13) | |||||

| Outcome | Model | Genotype | 0N (%) | 1 N (%) | OR (95% CI) | P/FDR P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACLF (0—single, 1—multiple) | Cod | D/D | 33 (32.7) | 15 (25.9) | 1.00 | 0.001/0.0096 |

| I/D | 58 (57.4) | 23 (39.7) | 0.87 (0.40; 1.90) | |||

| I/I | 10 (9.9) | 20 (34.5) | 4.40 (1.66; 11.65) | |||

| Dom | D/D | 33 (32.7) | 15 (25.9) | 1.00 | 0.365/0.631 | |

| I/D-I/I | 68 (67.3) | 43 (74.1) | 1.39 (0.68; 2.86) | |||

| Rec | D/D-I/D | 91 (90.1) | 38 (65.5) | 1.00 | 0.0002/0.0096 | |

| I/I | 10 (9.9) | 20 (34.5) | 4.79 (2.05; 11.19) | |||

| Over | D/D-I/I | 43 (42.6) | 35 (60.3) | 1.00 | 0.031/0.099 | |

| I/D | 58 (57.4) | 23 (39.7) | 0.49 (0.25; 0.94) | |||

| ACLS (0—no, 1—yes) | Cod | D/D | 12 (38.7) | 36 (28.1) | 1.00 | 0.468/0.702 |

| I/D | 13 (41.9) | 68 (53.1) | 1.74 (0.72; 4.21) | |||

| I/I | 6 (19.4) | 24 (18.8) | 1.33 (0.44; 4.04) | |||

| Dom | D/D | 12 (38.7) | 36 (28.1) | 1.00 | 0.257/0.549 | |

| I/D-I/I | 19 (61.3) | 92 (71.9) | 1.61 (0.71; 3.66) | |||

| Rec | D/D-I/D | 25 (80.6) | 104 (81.2) | 1.00 | 0.939/1.0 | |

| I/I | 6 (19.4) | 24 (18.8) | 0.96 (0.36; 2.60) | |||

| Over | D/D-I/I | 18 (58.1) | 60 (46.9) | 1.00 | 0.263/0.549 | |

| I/D | 13 (41.9) | 68 (53.1) | 1.57 (0.71; 3.47) | |||

| ACLRP (0—no, 1—yes) | Cod | D/D | 28 (23.3) | 20 (51.3) | 1.00 | 0.003/0.018 |

| I/D | 69 (57.5) | 12 (30.8) | 0.24 (0.11; 0.56) | |||

| I/I | 23 (19.2) | 7 (17.9) | 0.43 (0.15; 1.18) | |||

| Dom | D/D | 28 (23.3) | 20 (51.3) | 1.00 | 0.001/0.0096 | |

| I/D-I/I | 92 (76.7) | 19 (48.7) | 0.29 (0.14; 0.62) | |||

| Rec | D/D-I/D | 97 (80.8) | 32 (82.1) | 1.00 | 0.865/0.944 | |

| I/I | 23 (19.2) | 7 (17.9) | 0.92 (0.36; 2.35) | |||

| Over | D/D-I/I | 51 (42.5) | 27 (69.2) | 1.00 | 0.003/0.018 | |

| I/D | 69 (57.5) | 12 (30.8) | 0.33 (0.15; 0.71) | |||

| ACLRC (0—no, 1—yes) | Cod | D/D | 37 (26.4) | 11 (57.9) | 1.00 | 0.006/0.024 |

| I/D | 73 (52.1) | 8 (42.1) | 0.37 (0.14; 0.99) | |||

| I/I | 30 (21.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 (0.00) | |||

| Dom | D/D | 37 (26.4) | 11 (57.9) | 1.00 | 0.007/0.026 | |

| I/D-I/I | 103 (73.6) | 8 (42.1) | 0.26 (0.10; 0.70) | |||

| Rec | D/D-I/D | 110 (78.6) | 19 (100.0) | 1.00 | 0.025/0.086 | |

| I/I | 30 (21.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 (0.00) | |||

| Over | D/D-I/I | 67 (47.9) | 11 (57.9) | 1.00 | 0.411/0.680 | |

| I/D | 73 (52.1) | 8 (42.1) | 0.67 (0.25; 1.76) |

| Outcome | Model | Genotype | 0N (%) | 1 N (%) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACLF (0—single, 1—multiple) | Cod | C/C | 62 (61.4) | 42 (71.2) | 1.00 | 0.444/0.687 |

| C/T | 35 (34.7) | 15 (25.4) | 0.63 (0.31; 1.30) | |||

| T/T | 4 (4.0) | 2 (3.4) | 0.74 (0.13; 4.21) | |||

| Dom | C/C | 62 (61.4) | 42 (71.2) | 1.00 | 0.207/0.549 | |

| C/T-T/T | 39 (38.6) | 17 (28.8) | 0.64 (0.32; 1.28) | |||

| Rec | C/C-C/T | 97 (96.0) | 57 (96.6) | 1.00 | 0.854/0.944 | |

| T/T | 4 (4.0) | 2 (3.4) | 0.85 (0.15; 4.79) | |||

| Over | C/C-T/T | 66 (65.3) | 44 (74.6) | 1.00 | 0.220/0.549 | |

| C/T | 35 (34.7) | 15 (25.4) | 0.64 (0.31; 1.31) | |||

| ACLS (0—no, 1—yes) | Cod | C/C | 19 (61.3) | 85 (65.9) | 1.00 | 0.850/0.944 |

| C/T | 11 (35.5) | 39 (30.2) | 0.79 (0.34; 1.82) | |||

| T/T | 1 (3.2) | 5 (3.9) | 1.12 (0.12; 10.13) | |||

| Dom | C/C | 19 (61.3) | 85 (65.9) | 1.00 | 0.632/0.798 | |

| C/T-T/T | 12 (38.7) | 44 (34.1) | 0.82 (0.36; 1.84) | |||

| Rec | C/C-C/T | 30 (96.8) | 124 (96.1) | 1.00 | 0.862/0.944 | |

| T/T | 1 (3.2) | 5 (3.9) | 1.21 (0.14; 10.74) | |||

| Over | C/C-T/T | 20 (64.5) | 90 (69.8) | 1.00 | 0.574/0.798 | |

| C/T | 11 (35.5) | 39 (30.2) | 0.79 (0.34; 1.80) | |||

| ACLRP (0—no, 1—yes) | Cod | C/C | 86 (71.7) | 18 (45.0) | 1.00 | 0.005/0.022 |

| C/T | 29 (24.2) | 21 (52.5) | 3.46 (1.62; 7.38) | |||

| T/T | 5 (4.2) | 1 (2.5) | 0.96 (0.11; 8.68) | |||

| Dom | C/C | 86 (71.7) | 18 (45.0) | 1.00 | 0.003/0.018 | |

| C/T-T/T | 34 (28.3) | 22 (55.0) | 3.09 (1.48; 6.47) | |||

| Rec | C/C-C/T | 115 (95.8) | 39 (97.5) | 1.00 | 0.616/0.798 | |

| T/T | 5 (4.2) | 1 (2.5) | 0.59 (0.07; 5.20) | |||

| Over | C/C-T/T | 91 (75.8) | 19 (47.5) | 1.00 | 0.001/0.0096 | |

| C/T | 29 (24.2) | 21 (52.5) | 3.47 (1.64; 7.33) | |||

| ACLRC (0—no, 1—yes) | Cod | C/C | 94 (66.7) | 10 (52.6) | 1.00 | 0.496/0.721 |

| C/T | 42 (29.8) | 8 (42.1) | 1.79 (0.66; 4.86) | |||

| T/T | 5 (3.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1.88 (0.20; 17.73) | |||

| Dom | C/C | 94 (66.7) | 10 (52.6) | 1.00 | 0.237/0.549 | |

| C/T-T/T | 47 (33.3) | 9 (47.4) | 1.80 (0.68; 4.73) | |||

| Rec | C/C-C/T | 136 (96.5) | 18 (94.7) | 1.00 | 0.725/0.870 | |

| T/T | 5 (3.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1.51 (0.17; 13.67) | |||

| Over | C/C-T/T | 99 (70.2) | 11 (57.9) | 1.00 | 0.287/0.574 | |

| C/T | 42 (29.8) | 8 (42.1) | 1.71 (0.64; 4.57) |

| Outcome | Model | Genotype | 0N (%) | 1 N (%) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACLF (0—single, 1—multiple) | Cod | A/A | 89 (88.1) | 39 (66.1) | 1.00 | 0.004/0.021 |

| A/G | 11 (10.9) | 17 (28.8) | 3.53 (1.51; 8.22) | |||

| G/G | 1 (1.0) | 3 (5.1) | 6.85 (0.69; 67.89) | |||

| Dom | A/A | 89 (88.1) | 39 (66.1) | 1.00 | 0.0009/0.0096 | |

| A/G-G/G | 12 (11.9) | 20 (33.9) | 3.80 (1.69; 8.54) | |||

| Rec | A/A-A/G | 100 (99.0) | 56 (94.9) | 1.00 | 0.116/0.348 | |

| G/G | 1 (1.0) | 3 (5.1) | 5.36 (0.54; 52.73) | |||

| Over | A/A-G/G | 90 (89.1) | 42 (71.2) | 1.00 | 0.005/0.022 | |

| A/G | 11 (10.9) | 17 (28.8) | 3.31 (1.43; 7.69) | |||

| ACLS (0—no, 1—yes) | Cod | A/A | 27 (87.1) | 101 (78.3) | 1.00 | 0.598/0.798 |

| A/G | 4 (12.9) | 24 (18.6) | 1.60 (0.51; 5.02) | |||

| G/G | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.1) | 0.00 | |||

| Dom | A/A | 27 (87.1) | 101 (78.3) | 1.00 | 0.252/0.549 | |

| A/G-G/G | 4 (12.9) | 28 (21.7) | 1.87 (0.60; 5.80) | |||

| Rec | A/A-A/G | 31 (100.0) | 125 (96.9) | 1.00 | 1.0/1.0 | |

| G/G | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.1) | 0.00 | |||

| Over | A/A-G/G | 27 (87.1) | 105 (81.4) | 1.00 | 0.440/0.687 | |

| A/G | 4 (12.9) | 24 (18.6) | 1.54 (0.49; 4.82) | |||

| ACLRP (0—no, 1—yes) | Cod | A/A | 94 (78.3) | 34 (85.0) | 1.00 | 0.611/0.798 |

| A/G | 23 (19.2) | 5 (12.5) | 0.60 (0.21; 1.71) | |||

| G/G | 3 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0.92 (0.09; 9.16) | |||

| Dom | A/A | 94 (78.3) | 34 (85.0) | 1.00 | 0.340/0.628 | |

| A/G-G/G | 26 (21.7) | 6 (15.0) | 0.64 (0.24; 1.68) | |||

| Rec | A/A-A/G | 117 (97.5) | 39 (97.5) | 1.00 | 1.0/1.0 | |

| G/G | 3 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 1.00 (0.10; 9.89) | |||

| Over | A/A-G/G | 97 (80.8) | 35 (87.5) | 1.00 | 0.322/0.618 | |

| A/G | 23 (19.2) | 5 (12.5) | 0.60 (0.21; 1.71) | |||

| ACLRC (0—no, 1—yes) | Cod | A/A | 111 (78.7) | 17 (89.5) | 1.00 | 0.718/0.870 |

| A/G | 26 (18.4) | 2 (10.5) | 0.50 (0.11; 2.31) | |||

| G/G | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 (0.00) | |||

| Dom | A/A | 111 (78.7) | 17 (89.5) | 1.00 | 0.240/0.549 | |

| A/G-G/G | 30 (21.3) | 2 (10.5) | 0.44 (0.10; 1.99) | |||

| Rec | A/A-A/G | 137 (97.2) | 19 (100.0) | 1.00 | 1.0/1.0 | |

| G/G | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 (0.00) | |||

| Over | A/A-G/G | 115 (81.6) | 17 (89.5) | 1.00 | 0.368/0.631 | |

| A/G | 26 (18.4) | 2 (10.5) | 0.52 (0.11; 2.39) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Łosińska, K.W.; Rzeszutko-Bełzowska, A.; Ficek, K.; Massidda, M.; Ghiani, G.M.; Cięszczyk, P.; September, A.V. Matrix Metalloproteinase Polymorphisms as Genetic Risk Factors for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Football Players: A Case–Control Study. Genes 2025, 16, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121505

Łosińska KW, Rzeszutko-Bełzowska A, Ficek K, Massidda M, Ghiani GM, Cięszczyk P, September AV. Matrix Metalloproteinase Polymorphisms as Genetic Risk Factors for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Football Players: A Case–Control Study. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121505

Chicago/Turabian StyleŁosińska, Kinga Wiktoria, Agata Rzeszutko-Bełzowska, Krzysztof Ficek, Myosotis Massidda, Giovanna Maria Ghiani, Paweł Cięszczyk, and Alison Victoria September. 2025. "Matrix Metalloproteinase Polymorphisms as Genetic Risk Factors for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Football Players: A Case–Control Study" Genes 16, no. 12: 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121505

APA StyleŁosińska, K. W., Rzeszutko-Bełzowska, A., Ficek, K., Massidda, M., Ghiani, G. M., Cięszczyk, P., & September, A. V. (2025). Matrix Metalloproteinase Polymorphisms as Genetic Risk Factors for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Football Players: A Case–Control Study. Genes, 16(12), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121505