Internal Validation of Mitochondrial DNA Control Region Using the Precision ID mtDNA Control Region Panel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Validation Parameters and Sample Description

2.2. DNA Extraction and Quantification

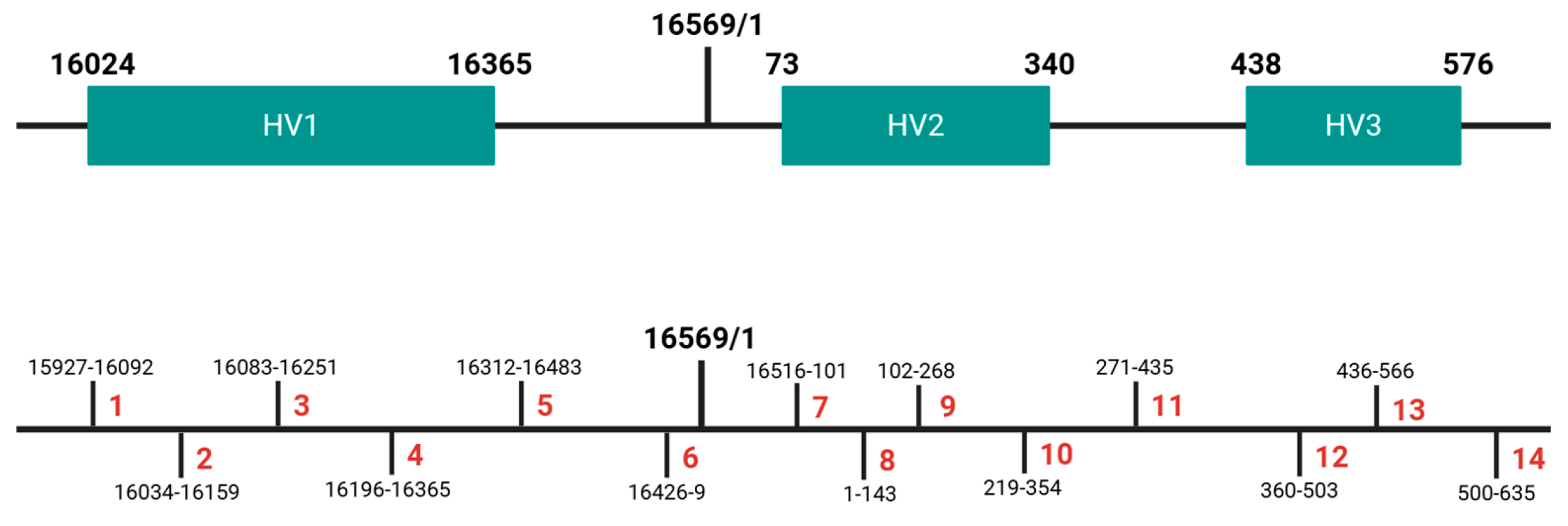

2.3. Library and Template Preparation

2.4. Sequencing and Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Minimum Read Depth

3.2. Sensitivity and Repeatability Assessment

3.3. Concordance Study

3.4. Reproducibility Analysis

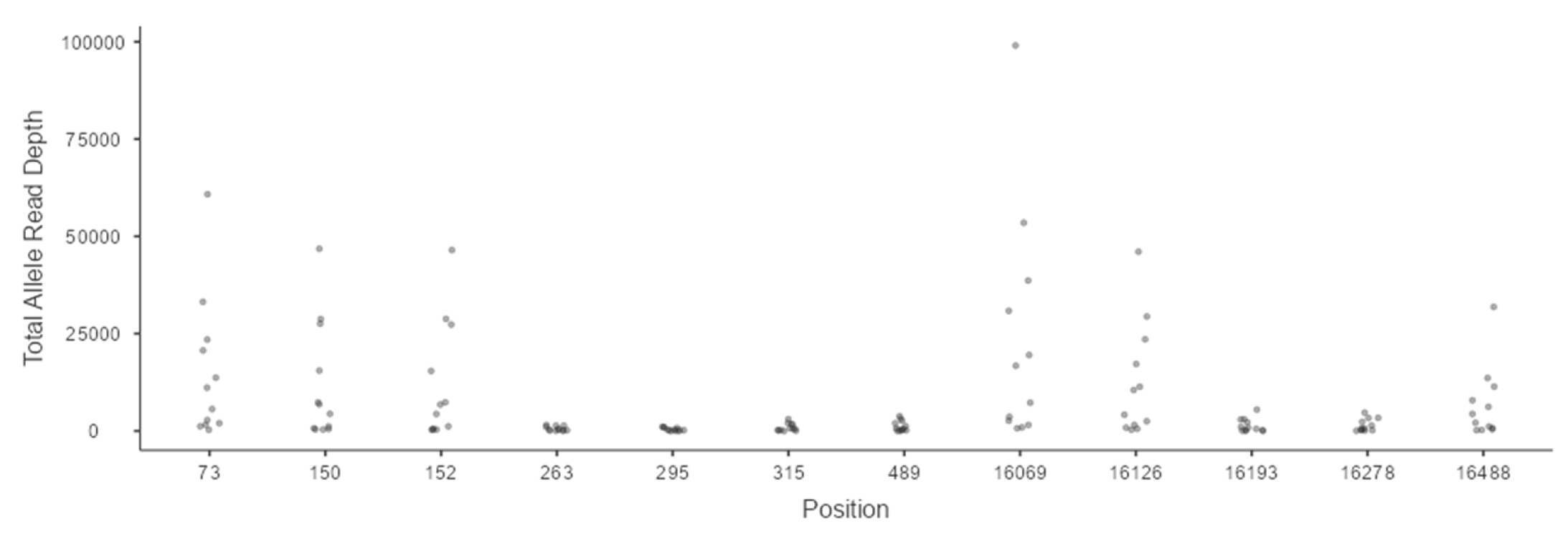

3.5. Heteroplasmy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crespillo Márquez, M.; Barrio Caballero, P.A.; Farfán Espuny, M.J. Aportaciones Y Avances de La Genética Forense En Los Sucesos Con Víctimas Múltiples. Rev. Española Med. Leg. 2023, 49, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeta, M.; Núñez, C.; Sosa, C.; Bolea, M.; Casalod, Y.; González-Andrade, F.; Roewer, L.; Martínez-Jarreta, B. Mitochondrial Diversity in Amerindian Kichwa and Mestizo Populations from Ecuador. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2011, 126, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, R.S.; Irwin, J.A.; Parson, W. Mitochondrial DNA Heteroplasmy in the Emerging Field of Massively Parallel Sequencing. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 18, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, M.; Iuvaro, A.; Strobl, C.; Nagl, S.; Huber, G.; Pelotti, S.; Pettener, D.; Luiselli, D.; Parson, W. Helena, the Hidden Beauty: Resolving the most Common West Eurasian mtDNA Control Region Haplotype by Massively Parallel Sequencing an Italian Population Sample. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 15, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandlik, J.S.; Patil, A.S.; Singh, S. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Platforms and Applications. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obal, M.; Zupanc, T.; Zupanič Pajnič, I. Comparison of the Optimal and Suboptimal Quantity of Mitotype Libraries using Next-Generation Sequencing. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2023, 138, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, B.; Yan, J. Application of Next-Generation Sequencing Technology in Forensic Science. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2014, 12, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krane, D.E.; Philpott, M.K. Using Laboratory Validation to Identify and Establish Limits to the Reliability of Probabilistic Genotyping Systems. In Handbook DNA Profiling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISFG—Isfg. Org. Available online: https://www.isfg.org/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- HOME|Swgdam. Available online: https://www.swgdam.org/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- ENFSI. Available online: https://enfsi.eu/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/66912.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Fisher Scientific, T. Precision ID mtDNA Panels with the HID Ion S5™/HID Ion GeneStudio™ S5 System Application Guide; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Waltham, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, C.; Parson, W.; Strobl, C.; Lagacé, R.; Short, M. MVC: An Integrated Mitochondrial Variant Caller for Forensics. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 51, S52–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihlar, J.C.; Amory, C.; Lagacé, R.; Roth, C.; Parson, W.; Budowle, B. Developmental Validation of a MPS Workflow with a PCR-Based Short Amplicon Whole Mitochondrial Genome Panel. Genes 2020, 11, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Li, L.; Zhang, G. Coverage Recommendation for Genotyping Analysis of Highly Heterologous Species using Next-Generation Sequencing Technology. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccinetto, C.; Sabbatini, D.; Serventi, P.; Rigato, M.; Salvoro, C.; Casamassima, G.; Margiotta, G.; De Fanti, S.; Sarno, S.; Staiti, N.; et al. Internal Validation and Improvement of Mitochondrial Genome Sequencing using the Precision ID mtDNA Whole Genome Panel. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandhagen, M.D.; Just, R.S.; Irwin, J.A. Validation of NGS for Mitochondrial DNA Casework at the FBI Laboratory. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 44, 102151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cihlar, J.C.; Peters, D.; Strobl, C.; Parson, W.; Budowle, B. The Lot-to-Lot Variability in the Mitochondrial Genome of Controls. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 47, 102298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMPOP. Available online: https://empop.online/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Parson, W.; Dür, A. EMPOP—A Forensic mtDNA Database. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2006, 1, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MITOMAP. Available online: https://www.mitomap.org/MITOMAP (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Senst, A.; Caliebe, A.; Scheurer, E.; Schulz, I. Validation and Beyond: Next Generation Sequencing of Forensic Casework Samples Including Challenging Tissue Samples from Altered Human Corpses using the MiSeq FGx System. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 67, 1382–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Børsting, C.; Morling, N. Next Generation Sequencing and its Applications in Forensic Genetics. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 18, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Ma, K.; Nie, Y.; Liu, W.; Jiao, H.; Zhou, H. Validation of Expressmarker mtDNA-SNP60: A Mitochondrial SNP Kit for Forensic Application. Electrophoresis 2016, 37, 2848–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parson, W.; Bandelt, H. Extended Guidelines for mtDNA Typing of Population Data in Forensic Science. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2007, 1, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J.; Yao, Y.; Guo, K.; Meng, Y.; Ji, A.; Kang, K.; Wang, L. Developmental Validation of the STRSeqTyper122 Kit for Massively Parallel Sequencing of Forensic STRs. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2024, 138, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.; Roman, M.G.; Harrel, M.; Hughes, S.; Larue, B.; Houston, R. Assessment of the ForenSeq mtDNA Control Region Kit and Comparison of Orthogonal Technologies. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2022, 59, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.L.; Stephens, K.M.; Walichiewicz, P.; Fleming, K.D.; Forouzmand, E.; Wu, S. Human Mitochondrial Control Region and mtGenome: Design and Forensic Validation of NGS Multiplexes, Sequencing and Analytical Software. Genes 2021, 12, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Huang, T. Characterization of Mitochondrial DNA Heteroplasmy using a Parallel Sequencing System. BioTechniques 2018, 48, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, C.; Sierra, B.; Álvarez, L.; Ramos, A.; Fernández, E.; Nogués, R.; Aluja, M.P. Frequency and Pattern of Heteroplasmy in the Control Region of Human Mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 2008, 67, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, J.D.; Stoljarova, M.; King, J.L.; Budowle, B. Massively Parallel Sequencing-Enabled Mixture Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Samples. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 132, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Tu, J.; Lu, Z. Recent Advances in Detecting Mitochondrial DNA Heteroplasmic Variations. Molecules 2018, 23, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Maximum Read Depth |

|---|---|

| H2O 1 | 96 |

| H2O 2 | 14 |

| H2O 3 | 39 |

| H2O 4 | 119 |

| Ctrl- 1 RS | 170 |

| Ctrl- 2 RS | 234 |

| Ctrl- 3 RS | 158 |

| Ctrl- 1 HR | 66 |

| Ctrl- 2 HR | 55 |

| Ctrl- 3 HR | 56 |

| Average | 100.7 |

| Sample | Concordance | Method | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| RS4 | 83% | Sanger | 263G, 309.2C *, 315.1C, 456T, 16304C, 16519C |

| NGS | 263G, 309.1C *, 315.1C, 456T, 16304C, 16519C | ||

| RS5 | 92.8% | Sanger | 73G, 152C, 199C, 250C, 263G, 309.1C, 315.1C, 494A, 16129A, 16148T, 16223T, 16391A, 16519C |

| NGS | 73G, 152C, 199C, 250C, 263G, 309.1C, 315.1C, 494A, 573.5C *, 16129A, 16148T, 16223T, 16391A, 16519C | ||

| RS6 | 100% | Sanger | 73G, 151T, 152C, 182T, 186A, 189C, 195C, 198T, 204C, 207A, 247del, 263G, 297G, 315.1C, 316A, 523del, 524del, 16037G, 16129A, 16187T, 16189C, 16223T, 16243C, 16278T, 16293G, 16294T, 16311C, 16360T, 16519C |

| NGS | 73G, 151T, 152C, 182T, 186A, 189C, 195C, 198T, 204C, 207A, 247del, 263G, 297G, 315.1C, 316A, 523del, 524del, 16037G, 16129A, 16187T, 16189C, 16223T, 16243C, 16278T, 16293G, 16294T, 16311C, 16360T, 16519C | ||

| RS7 | 100% | Sanger | 73G, 151T, 152C, 182T, 186A, 189C, 195C, 198T, 204C, 207A, 247del, 263G, 297G, 315.1C, 316A, 523del, 524del, 16037G, 16129A, 16187T, 16189C, 16223T, 16243C, 16278T, 16293G, 16294T, 16311C, 16360T, 16519C |

| NGS | 73G, 151T, 152C, 182T, 186A, 189C, 195C, 198T, 204C, 207A, 247del, 263G, 297G, 315.1C, 316A, 523del, 524del, 16037G, 16129A, 16187T, 16189C, 16223T, 16243C, 16278T, 16293G, 16294T, 16311C, 16360T, 16519C |

| Sample | Polymorphisms (minor:major) | M1 (%:%) | M2 (%:%) | M3 (%:%) | M4 (%:%) | M5 (%:%) | M6 (%:%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Het1 | 152 (C:T) | 61:33 | 52:42 | 43:52 | 31:66 | 17:81 | 14:84 |

| 295 (T:C) | 57:40 | 46:51 | 38:56 | 34:62 | 21:75 | 17:78 | |

| 462 (T:C) | 79:20 | 67:33 | 59:41 | 44:56 | 27:73 | 23:77 | |

| 489 (C:T) | 78:21 | 63:36 | 54:45 | 43:57 | 23:78 | 21:79 | |

| 16069 (T:C) | 70:30 | 60:40 | 48:52 | 34:66 | 19:81 | 15:85 | |

| 16093 (T:C) | 75:25 | 65:35 | 55:45 | 41:59 | 27:73 | 24:76 | |

| 16126 (C:T) | 72:27 | 63:37 | 52:48 | 37:63 | 21:79 | 18:82 | |

| 16193 (T:C) | 72:25 | 64:32 | 50:45 | 36:62 | 22:76 | 18:79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lechuga-Morillas, E.; Saiz, M.; Vinueza-Espinosa, D.C.; Gálvez, X.; Medina-Lozano, M.I.; Medina-Lozano, R.; Santisteban, F.; Álvarez, J.C.; Lorente, J.A. Internal Validation of Mitochondrial DNA Control Region Using the Precision ID mtDNA Control Region Panel. Genes 2025, 16, 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121504

Lechuga-Morillas E, Saiz M, Vinueza-Espinosa DC, Gálvez X, Medina-Lozano MI, Medina-Lozano R, Santisteban F, Álvarez JC, Lorente JA. Internal Validation of Mitochondrial DNA Control Region Using the Precision ID mtDNA Control Region Panel. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121504

Chicago/Turabian StyleLechuga-Morillas, Esther, María Saiz, Diana C. Vinueza-Espinosa, Xiomara Gálvez, María Isabel Medina-Lozano, Rosario Medina-Lozano, Francisco Santisteban, Juan Carlos Álvarez, and José Antonio Lorente. 2025. "Internal Validation of Mitochondrial DNA Control Region Using the Precision ID mtDNA Control Region Panel" Genes 16, no. 12: 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121504

APA StyleLechuga-Morillas, E., Saiz, M., Vinueza-Espinosa, D. C., Gálvez, X., Medina-Lozano, M. I., Medina-Lozano, R., Santisteban, F., Álvarez, J. C., & Lorente, J. A. (2025). Internal Validation of Mitochondrial DNA Control Region Using the Precision ID mtDNA Control Region Panel. Genes, 16(12), 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121504