APOE Genotype and Endothelial Biomarkers: Towards Personalized Cardiovascular Screening

Abstract

1. Introduction

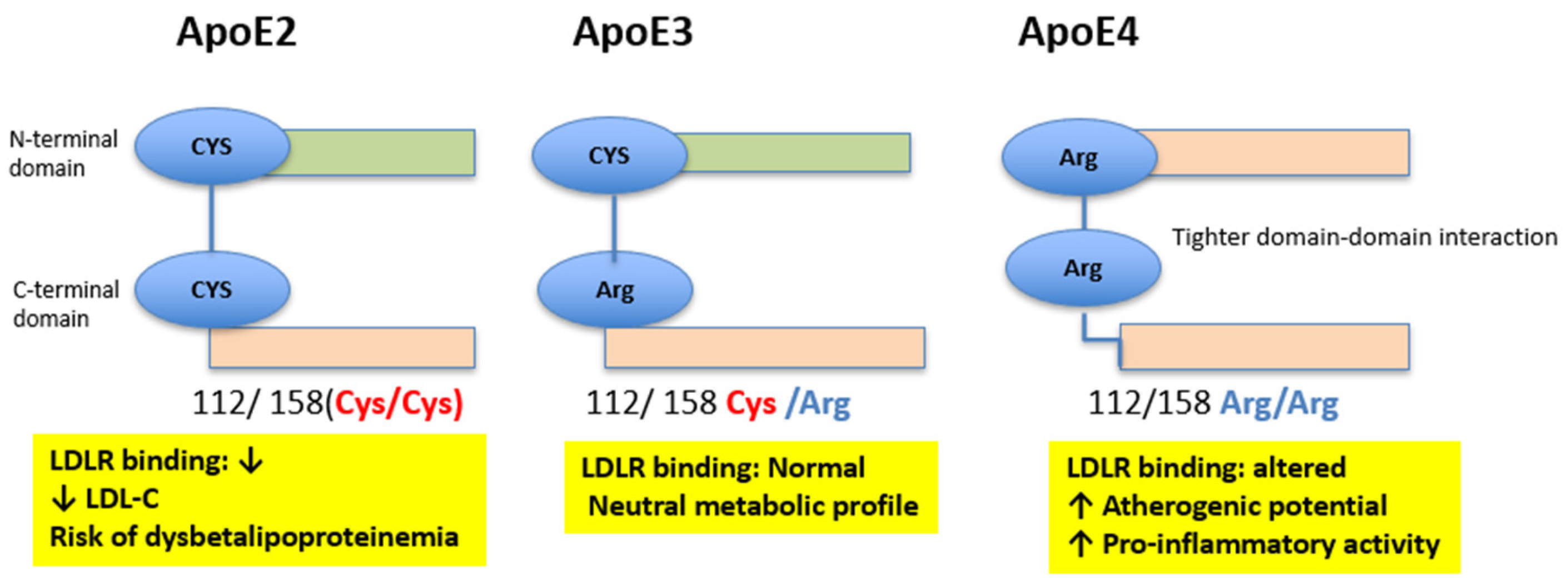

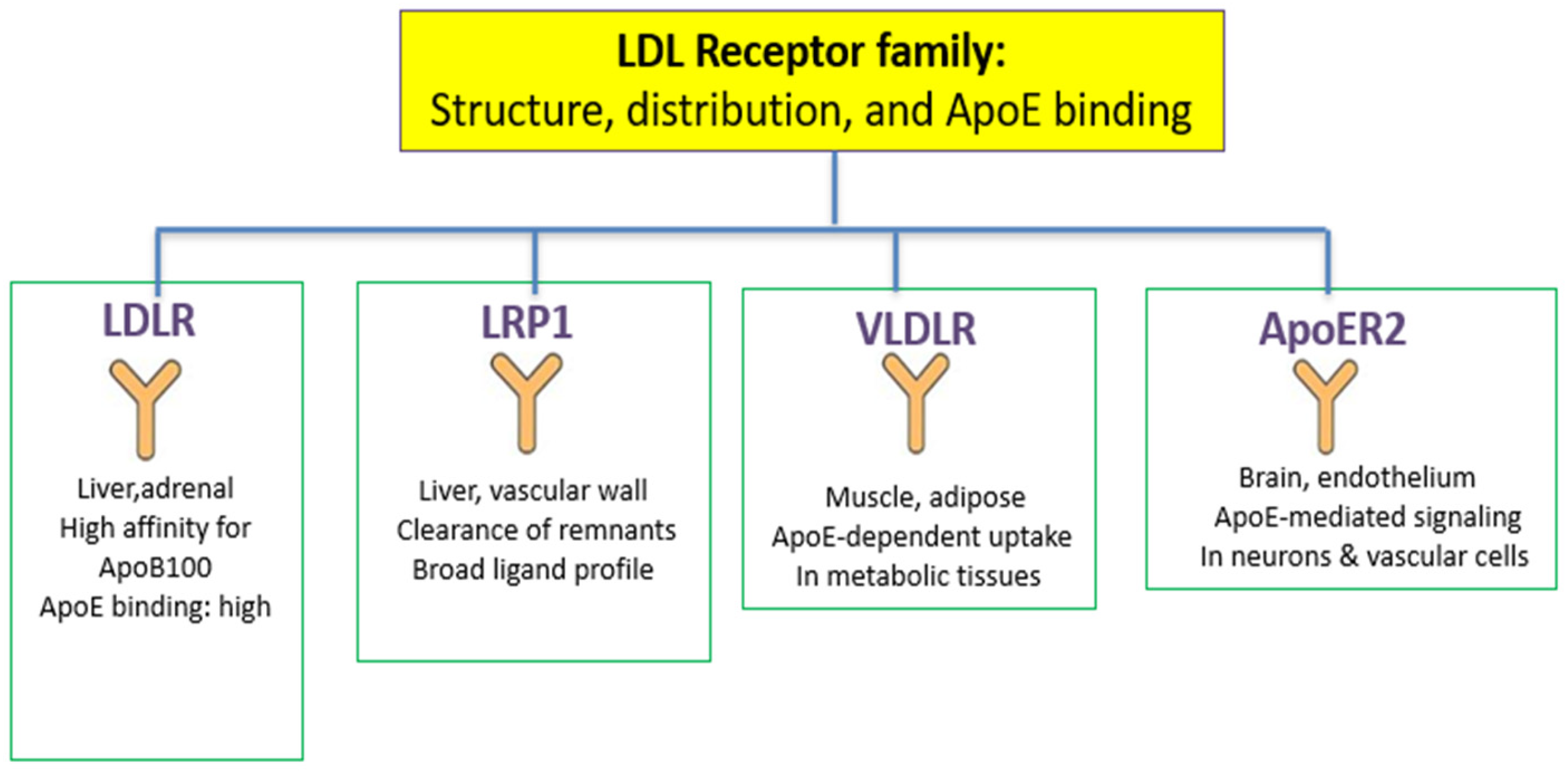

2. Apolipoprotein E: Structure, Polymorphisms, and Functions

3. ApoE in the Cardiovascular Scenario Stratification

4. ApoE and Endothelial Function

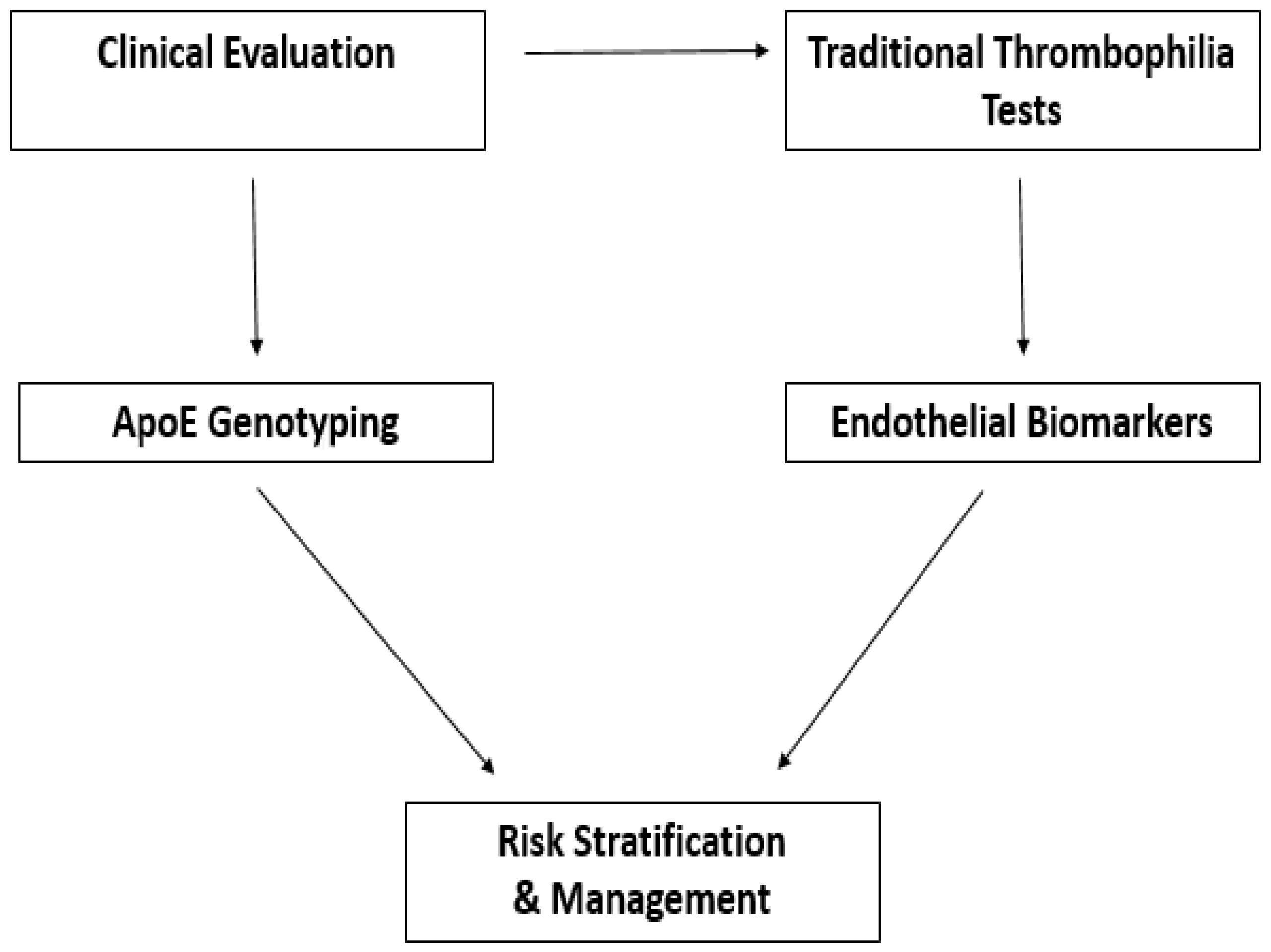

5. Endothelial Biomarkers: State of the Art

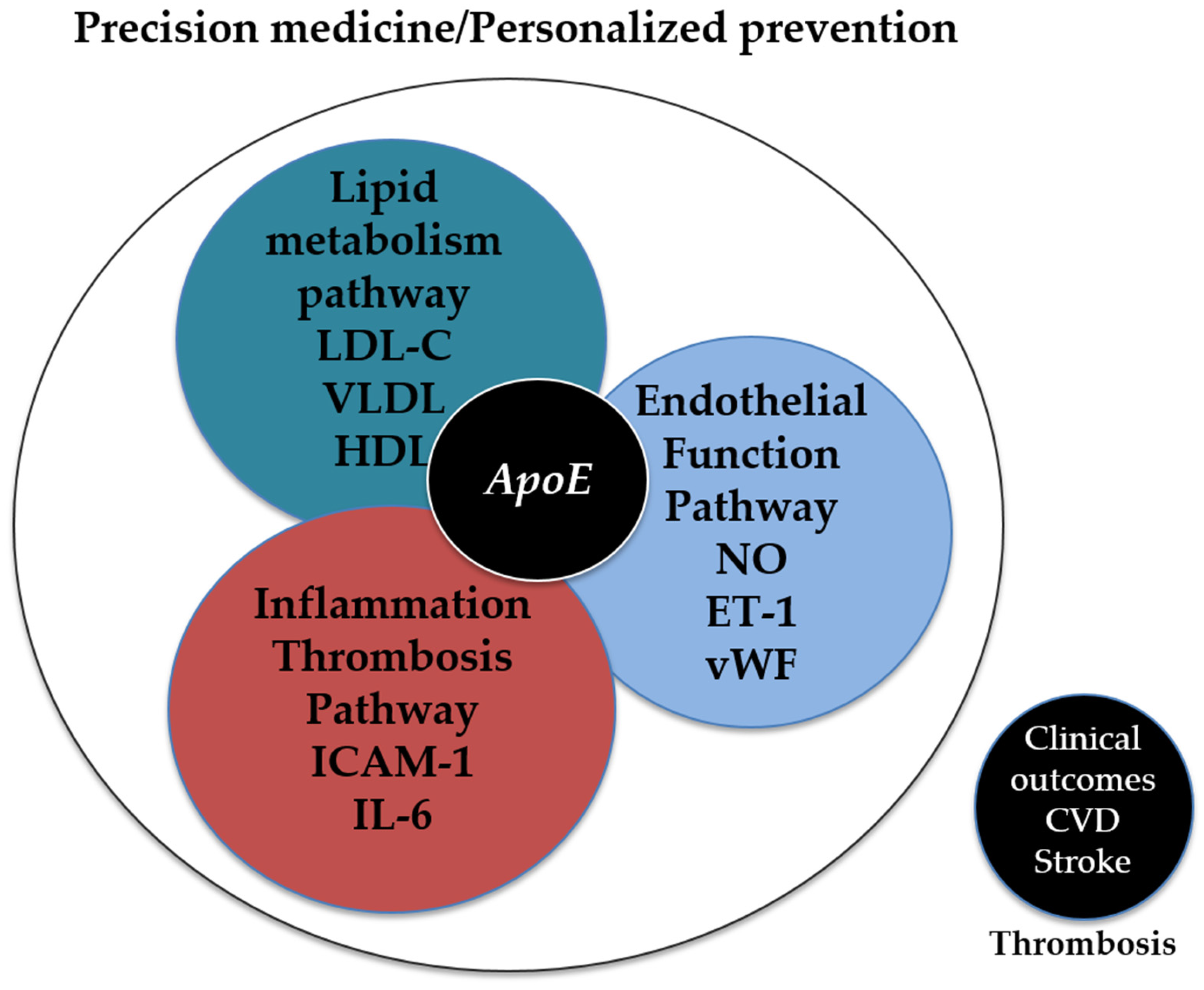

6. Integration of ApoE and Endothelial Biomarkers in Clinical Screening

6.1. Indications for ApoE Genotyping Testing

6.1.1. Targeting Endothelial Biomarkers: Which Patients Benefit Most?

6.1.2. How Can Biomarker Data Be Integrated with Traditional Thrombophilia Screening?

6.2. Expected Benefits

6.2.1. Improved Accuracy in Risk Stratification

6.2.2. Targeted Patient Selection for Treatment or Monitoring

6.2.3. Reduction in Low-Yield Tests

6.3. Current Limitations and Challenges: Costs and Standardization

7. Future Perspectives and Research Directions

7.1. The Need for Large-Scale Longitudinal Clinical Studies

7.2. Integration into Precision Medicine Protocols

7.3. Potential of Artificial Intelligence and Big Data to Analyze Combined Genetic and Functional Variables

7.4. Toward a Clinical Decision Algorithm Including ApoE

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chong, B.; Jayabaskaran, J.; Jauhari, S.M.; Chan, S.P.; Goh, R.; Kueh, M.T.W.; Li, H.; Chin, Y.H.; Kong, G.; Anand, V.V.; et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Projections from 2025 to 2050. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middeldorp, S.; Nieuwlaat, R.; Baumann Kreuziger, L.; Coppens, M.; Houghton, D.; James, A.H.; Lang, E.; Moll, S.; Myers, T.; Bhatt, M.; et al. American Society of Hematology 2023 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Thrombophilia testing. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 7101–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahley, R.W. Apolipoprotein E: From cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative disorders. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 94, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Shapiro, M.D. Apolipoproteins in vascular biology and atherosclerotic disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 19, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashi, Y. Noninvasive Assessment of Vascular Function. JACC Asia 2024, 4, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahley, R.W.; Rall, S.C. Apolipoprotein E: Far More Than a Lipid Transport Protein. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2000, 1, 507–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahley, R.W. Apolipoprotein E: Cholesterol Transport Protein with Expanding Role in Cell Biology. Science 1988, 240, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Mahley, R.W. Apolipoprotein E: Structure and function in lipid metabolism, neurobiology, and Alzheimer’s diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 72, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisgraber, K.H. Apolipoprotein E distribution among human plasma lipoproteins: Role of the cysteine-arginine interchange at residue 112. J. Lipid Res. 1990, 31, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.P.; Singh, M.; Mastana, S.S. APOE distribution in world populations with new data from India and the UK. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2009, 33, 279–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Li, B.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Chen, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Zeng, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Apolipoprotein E E3/E4 genotype is associated with an increased risk of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fullerton, S.M.; Clark, A.G.; Weiss, K.M.; Nickerson, D.A.; Taylor, S.L.; Stengård, J.H.; Salomaa, V.; Vartiainen, E.; Perola, M.; Boerwinkle, E.; et al. Apolipoprotein E Variation at the Sequence Haplotype Level: Implications for the Origin and Maintenance of a Major Human Polymorphism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 67, 881–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getz, G.S.; Reardon, C.A. ApoE knockout and knockin mice: The history of their contribution to the understanding of atherogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Hong, L.; Liu, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, W.; Pan, R.; Lu, W.; Luo, Q.; Gao, S.; et al. Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) orchestrates adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic disorders through NLRP3 inflammasome. Mol. Biomed. 2023, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofre-Monseny, L.; Minihane, A.M.; Rimbach, G. Impact of apoE genotype on oxidative stress, inflammation and disease risk. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Shinohara, M.; Yamazaki, A.; Ren, Y.; Asmann, Y.W.; Kanekiyo, T.; Bu, G. ApoE (Apolipoprotein E) in Brain Pericytes Regulates Endothelial Function in an Isoform-Dependent Manner by Modulating Basement Membrane Components. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhao, J.; Meng, F.; He, F.; Ni, J.; Fu, Y. The vascular contribution of apolipoprotein E to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2024, 147, 2946–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukase, T.; Dohi, T.; Chikata, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Endo, H.; Doi, S.; Nishiyama, H.; Kato, Y.; Okai, I.; Iwata, H.; et al. Serum apolipoprotein E levels predict residual cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic coronary syndrome undergoing first percutaneous coronary intervention and on-statin treatment. Atherosclerosis 2021, 333, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiq, S.; Ashiq, K. The association of apolipoprotein-E (APOE) gene polymorphisms with coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 2021, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumsden, A.L.; Mulugeta, A.; Zhou, A.; Hyppönen, E. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype-associated disease risks: A phenome-wide, registry-based, case-control study utilising the UK Biobank. eBioMedicine 2020, 59, 102954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Ren, X.; Zhang, L.; Dong, H.; Lu, X.; Feng, W. Apolipoprotein E Gene Polymorphism and Coronary Artery Disease Risk Among Patients in Northwest China. Pharm. Pers. Med. 2021, 14, 1591–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, B.; Wang, H.; Wei, G.; Chen, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. Apolipoprotein E E3/E4 genotype is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated with coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.-Q.; Ren, H.; Banh, H.L.; Liu, M.-Z.; Xu, P.; Fang, P.-F.; Xiang, D.-X. The Associations between Apolipoprotein E Gene Epsilon2/Epsilon3/Epsilon4 Polymorphisms and the Risk of Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.R.; Lei, Y.Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, N.; Shi, J.P. Association between apolipoprotein E polymorphisms and premature coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM 2017, 55, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, G.; Parmar, K.; Amrutiya, V.; Patel, Y.; Patel, D. Abstract P3035: Assessing the Influence of ApoE Gene Polymorphisms on the Risk of Developing Cardiovascular Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus patients: A Systematic Review. Circulation 2025, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Deng, Q.; Guo, X.; Deng, X.; Zhong, W.; Zhong, Z. Association between apolipoprotein E gene polymorphism and the risk of coronary artery disease in Hakka postmenopausal women in southern China. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarron, M.O.; Delong, D.; Alberts, M.J. APOE genotype as a risk factor for ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Neurology 1999, 53, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, J.; Ke, J.; Zhang, H. Association of Apolipoprotein E Gene Polymorphism with Ischemic Stroke in Coronary Heart Disease Patients Treated with Medium-intensity Statins. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 2459–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemello, K.; Guedon, A.F.; Techer, R.; Jaafar, A.K.; Guilhen, S.; Swietek, M.J.; Lambert, G.; Gallo, A. Apolipoprotein E Plasma Concentrations Are Predictive of Recurrent Strokes: Insights from the SPARCL Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e036630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granér, M.; Kahri, J.; Varpula, M.; Salonen, R.M.; Nyyssönen, K.; Jauhiainen, M.; Nieminen, M.S.; Syvänne, M.; Taskinen, M.-R. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism is associated with both carotid and coronary atherosclerosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2008, 18, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culleton, S.; Niu, M.; Alexander, M.; McNally, J.S.; Yuan, C.; Parker, D.; Baradaran, H. Extracranial carotid artery atherosclerotic plaque and APOE polymorphisms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1155916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doliner, B.; Dong, C.; Blanton, S.H.; Gardener, H.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Sacco, R.L.; Demmer, R.T.; Desvarieux, M.; Rundek, T. Apolipoprotein E Gene Polymorphism and Subclinical Carotid Atherosclerosis: The Northern Manhattan Study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018, 27, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio-Fernández, R.; Tristão-Pereira, C.; Carlos Silla-Castro, J.; Callejas, S.; Oliva, B.; Fernandez-Nueda, I.; Garcia-Lunar, I.; Perez-Herreras, C.; María Ordovás, J.; Martin, P.; et al. Apolipoprotein E-ε2 and Resistance to Atherosclerosis in Midlife: The PESA Observational Study. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, C.; Luo, M. Apolipoprotein E Gene ε4 Allele is Associated with Atherosclerosis in Multiple Vascular Beds. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 5039–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, J.; Mehlig, K.; Leander, K.; Strandhagen, E.; Björck, L.; Thelle, D.S.; Lissner, L.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Nyberg, F. Interaction of apolipoprotein E genotype with smoking and physical inactivity on coronary heart disease risk in men and women. Atherosclerosis 2012, 220, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grammer, T.B.; Hoffmann, M.M.; Scharnagl, H.; Kleber, M.E.; Silbernagel, G.; Pilz, S.; Tomaschitz, A.; Lerchbaum, E.; Siekmeier, R.; März, W. Smoking, apolipoprotein E genotypes, and mortality (the Ludwigshafen RIsk and Cardiovascular Health study). Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lo Sasso, G.; Schlage, W.K.; Boué, S.; Veljkovic, E.; Peitsch, M.C.; Hoeng, J. The Apoe−/− mouse model: A suitable model to study cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in the context of cigarette smoke exposure and harm reduction. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivipelto, M.; Rovio, S.; Ngandu, T.; Kåreholt, I.; Eskelinen, M.; Winblad, B.; Hachinski, V.; Cedazo-Minguez, A.; Soininen, H.; Tuomilehto, J.; et al. Apolipoprotein E ɛ4 magnifies lifestyle risks for dementia: A population-based study. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 12, 2762–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minihane, A.M.; Jofre-Monseny, L.; Olano-Martin, E.; Rimbach, G. ApoE genotype, cardiovascular risk and responsiveness to dietary fat manipulation. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2007, 66, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio Moreno, J.; López-Miranda, J.; Pérez-Jiménez, F. Influencia de los factores genéticos y ambientales en el metabolismo lipídico y riesgo cardiovascular asociado al gen apoE. Med. Clín. 2006, 127, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F.; Mendonca, M.I.; Sa, D.; Abreu, G.; Henriques, E.; Rodrigues, M.; Freitas, S.; Borges, S.; Guerra, G.; Drumond, A.; et al. Gene-gene and gene-environment interaction in coronary artery disease risk. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, ehae666.1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul Rasmussen, I.; Rasmussen, K.L.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Frikke-Schmidt, R. Impact of cardiovascular risk factors and genetics on 10-year absolute risk of dementia: Risk charts for targeted prevention. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 4024–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, S.; Maqbool, T.; Qureshi, J.A.; Altaf, A.; Naz, S.; Azhar, M.M.; Ullah, I.; Shah, T.A.; Qamar, M.U.; Salamatullah, A.M. Apolipoprotein E Gene Variation in Pakistani Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes with and without Cardiovascular Complications. Medicina 2024, 60, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjalainen, J.-P.; Mononen, N.; Hutri-Kähönen, N.; Lehtimäki, M.; Juonala, M.; Ala-Korpela, M.; Kähönen, M.; Raitakari, O.; Lehtimäki, T. The effect of apolipoprotein E polymorphism on serum metabolome—A population-based 10-year follow-up study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.C.; Patra, K.; Giannisis, A.; Niesnerova, A.; Nandakumar, R.; Ellis, E.; Oliveira, T.G.; Nielsen, H.M. APOE genotype dictates lipidomic signatures in primary human hepatocytes. J. Lipid Res. 2024, 65, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.G.; March, Z.M.; Stephenson, R.A.; Narayan, P.S. Apolipoprotein E in lipid metabolism and neurodegenerative disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 34, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Bian, J.-T.; Grizelj, I.; Cavka, A.; Phillips, S.A.; Makino, A.; Mazzone, T. Apolipoprotein E Enhances Endothelial-NO Production by Modulating Caveolin 1 Interaction With Endothelial NO Synthase. Hypertension 2012, 60, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Fang, L.; Mo, P.; Chen, C.; Ji, Y.; Pang, L.; Chen, H.; Deng, Y.; Ou, W.; Liu, S.-M. Apoe-knockout induces strong vascular oxidative stress and significant changes in the gene expression profile related to the pathways implicated in redox, inflammation, and endothelial function. Cell Signal. 2023, 108, 110696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, M.; Kawashima, S.; Yamashita, T.; Hirase, T.; Namiki, M.; Inoue, N.; Hirata, K.-I.; Yasui, H.; Sakurai, H.; Yoshida, Y.; et al. Overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase accelerates atherosclerotic lesion formation in apoE-deficient mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nakashima, Y.; Raines, E.W.; Plump, A.S.; Breslow, J.L.; Ross, R. Upregulation of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 at Atherosclerosis-Prone Sites on the Endothelium in the ApoE-Deficient Mouse. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998, 18, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stannard, A.K.; Riddell, D.R.; Sacre, S.M.; Tagalakis, A.D.; Langer, C.; von Eckardstein, A.; Cullen, P.; Athanasopoulos, T.; Dickson, G.; Owen, J.S. Cell-derived Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) Particles Inhibit Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) Expression in Human Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 46011–46016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchareychas, L.; Raffai, R.L. Apolipoprotein E and Atherosclerosis: From Lipoprotein Metabolism to MicroRNA Control of Inflammation. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2018, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, A.B.; Balcıoğlu, Ö.; Özcem, B.; Ergoren, M.Ç. APOE Gene Variation’s Impact on Cardiovascular Health: A Case-Control Study. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.; Yanagisawa, M. Endothelin: 30 Years From Discovery to Therapy. Hypertension 2019, 74, 1232–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenting, P.J.; Christophe, O.D.; Denis, C.V. Von Willebrand factor biosynthesis, secretion, and clearance: Connecting the far ends. Blood 2015, 125, 2019–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladikou, E.E.; Sivaloganathan, H.; Milne, K.M.; Arter, W.E.; Ramasamy, R.; Saad, R.; Stoneham, S.M.; Philips, B.; Eziefula, A.C.; Chevassut, T. Von Willebrand factor (vWF): Marker of endothelial damage and thrombotic risk in COVID-19? Clin. Med. 2020, 20, e178–e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, A.; Lillicrap, D.; Yacob, M. Role of von Willebrand factor in venous thromboembolic disease. JVS-Vasc. Sci. 2022, 3, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Cui, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; You, C. Causal role of endothelial dysfunction in ischemic stroke and its subtypes: A two-stage analysis. SLAS Technol. 2025, 33, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kaur, R.; Kumari, P.; Pasricha, C.; Singh, R. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1: Gatekeepers in various inflammatory and cardiovascular disorders. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 548, 117487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Zhang, H.; Hill, M.A.; Zhang, C.; Park, Y. Interaction of IL-6 and TNF-α contributes to endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetic mouse hearts. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.N.; deGoma, E.; Shapiro, M.D. IL-6 and Cardiovascular Risk: A Narrative Review. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2024, 27, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagarsamy, J.; Jaeschke, A.; Hui, D.Y. Apolipoprotein E in Cardiometabolic and Neurological Health and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utermann, G.; Hees, M.; Steinmetz, A. Polymorphism of apolipoprotein E and occurrence of dysbetalipoproteinaemia in man. Nature 1977, 269, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Sun, L.-M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, H.-T.; Dong, Z.; Wang, L.-Q.; Wang, M.-L. Association between Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and myocardial infarction risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. FEBS Open Bio 2015, 5, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aalto-Setala, K.; Zhang, M.-D.; Gu, W.; Qiao, S.-B.; Zhu, E.-J.; Zhao, Q.-M.; Lv, S.-Z. Apolipoprotein E Gene Polymorphism and Risk for Coronary Heart Disease in the Chinese Population: A Meta-Analysis of 61 Studies Including 6634 Cases and 6393 Controls. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.W.F.; Schaefer, E.J.; Larson, M.G.; Ordovas, J.M. Apolipoprotein E Alleles and Risk of Coronary Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996, 16, 1250–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, A.M.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Ye, Z.; Wensley, F.; Dahlin, A.; Ahlbom, A.; Keavney, B.; Collins, R.; Wiman, B.; de Faire, U.; et al. Association of Apolipoprotein E Genotypes with Lipid Levels and Coronary Risk. JAMA 2007, 298, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A.; Shah, T.; Prieto, D.; Zhang, W.; Price, J.; Fowkes, G.R.; Cooper, J.; Talmud, P.J.; Humphries, S.E.; Sundstrom, J.; et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype, cardiovascular biomarkers and risk of stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 015 stroke cases and pooled analysis of primary biomarker data from up to 60 883 individuals. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopal, C.; van der Graaf, Y.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Westerink, J.; Visseren, F.L.J. Influence of APOE-2 genotype on the relation between adiposity and plasma lipid levels in patients with vascular disease. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 39, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, A.D.; Solomon, G.A.E.; Blom, D.J. Dysbetalipoproteinaemia: A mixed hyperlipidaemia of remnant lipoproteins due to mutations in apolipoprotein E. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2014, 51, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, K.; Méthot, J.; Brisson, D.; Gaudet, D. Etiology and risk of lactescent plasma and severe hypertriglyceridemia. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2011, 5, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopal, C.; Retterstøl, K.; Sjouke, B.; Hovingh, G.K.; Ros, E.; de Graaf, J.; Dullaart, R.P.F.; Bertolini, S.; Visseren, F.L.J. Vascular risk factors, vascular disease, lipids and lipid targets in patients with familial dysbetalipoproteinemia: A European cross-sectional study. Atherosclerosis 2015, 240, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, H.E.; Rodriguez, B.; Havlik, R.; Ferrucci, L.; Foley, D.; Curb, J.D.; Harris, T.B. Apo E genotype, diabetes, and peripheral arterial disease in older men: The Honolulu Asia-Aging Study. Genet. Epidemiol. 2000, 19, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradela, R.S.; Farias-Itao, D.S.; Leite, R.E.P.; Pasqualucci, C.A.; Grinberg, L.T.; Naslavsky, M.S.; Zatz, M.; Nitrini, R.; Jacob-Filho, W.; Suemoto, C.K. Apolipoprotein E ε2 allele is associated with lower risk of carotid artery obstruction in a population-based autopsy study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 32, 107229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, W.; Gan, Q.; Lei, M.; Gong, B.; Zhang, C.; Henrique, J.S.; Han, J.; Tian, H.; Tao, Q.; et al. The influences of ApoE isoforms on endothelial adherens junctions and actin cytoskeleton responding to mCRP. Angiogenesis 2024, 27, 861–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Rong, G.; Huang, P.; Wang, F.; Xu, T. Dissecting the Association of Apolipoprotein E Gene Polymorphisms with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Coronary Artery Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 838547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanas-Barca, M.; de Castro-Orós, I.; Mateo-Gallego, R.; Cofán, M.; Plana, N.; Puzo, J.; Burillo, E.; Martín-Fuentes, P.; Ros, E.; Masana, L.; et al. Apolipoprotein E gene mutations in subjects with mixed hyperlipidemia and a clinical diagnosis of familial combined hyperlipidemia. Atherosclerosis 2012, 222, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba-Falek, O.; Larifla, L.; Armand, C.; Bangou, J.; Blanchet-Deverly, A.; Numeric, P.; Fonteau, C.; Michel, C.-T.; Ferdinand, S.; Bourrhis, V.; et al. Association of APOE gene polymorphism with lipid profile and coronary artery disease in Afro-Caribbeans. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmitko, P.E.; Wang, C.-H.; Weisel, R.D.; de Almeida, J.R.; Anderson, T.J.; Verma, S. New Markers of Inflammation and Endothelial Cell Activation. Circulation 2003, 108, 1917–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-J.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Sharrett, A.R.; Smith, L.C.; Davis, C.E.; Gotto, A.M.; Boerwinkle, E. Circulating Adhesion Molecules VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin in Carotid Atherosclerosis and Incident Coronary Heart Disease Cases. Circulation 1997, 96, 4219–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzoulaki, I.; Murray, G.D.; Lee, A.J.; Rumley, A.; Lowe, G.D.O.; Fowkes, F.G.R. C-Reactive Protein, Interleukin-6, and Soluble Adhesion Molecules as Predictors of Progressive Peripheral Atherosclerosis in the General Population. Circulation 2005, 112, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Zheng, L.; Jiang, M.; Jia, R.; Zhang, X.; Quan, Q.; Du, G.; Shen, D.; Zhao, X.; Sun, W.; et al. Circulating microparticles in patients with coronary heart disease and its correlation with interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 6437–6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drenjancevic, I.; Jukic, I.; Stupin, A.; Cosic, A.; Stupin, M.; Selthofer-Relatic, K. The Markers of Endothelial Activation. In Endothelial Dysfunction—Old Concepts and New Challenges; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hanig, J.P.; De Felice, A.F. Biomarkers of endothelial cell activation: Candidate markers for drug-induced vasculitis in patients or drug-induced vascular injury in animals. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2012, 56, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallinga-Thie, G.M.; Hovingh, G.K. Towards network analysis to understand the genetic architecture of blood lipids: Do the inclusion of age-dependency helps to identify seven novel loci? Atherosclerosis 2014, 235, 642–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Shu, Y.; Lu, D. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism is associated with lower extremity deep venous thrombosis: Color-flow Doppler ultrasound evaluation. Lipids Health Dis. 2014, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagato, L.C.; de Souza Pinhel, M.A.; de Godoy, J.M.P.; Souza, D.R.S. Association of ApoE genetic polymorphisms with proximal deep venous thrombosis. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2011, 33, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, V.; Konaniah, E.S.; Herz, J.; Gerard, R.D.; Jung, E.; Yuhanna, I.S.; Ahmed, M.; Hui, D.Y.; Mineo, C.; Shaul, P.W. Genetic variants of ApoE and ApoER2 differentially modulate endothelial function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13493–13498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieker, C.; Migliavacca, E.; Vaucher, A.; Mayer, F.C.; Baud, G.; Marquis, J.; Charpagne, A.; Hegde, N.; Guignard, L.; McLachlan, M.; et al. Apolipoprotein E4 Expression Causes Gain of Toxic Function in Isogenic Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Endothelial Cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, E195–E207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, P.; Kumar, N.; Ahluwalia, J.; Das, R.; Varma, N.; Suri, V.; Senee, H. Thrombophilic risk factors are laterally associated with Apolipoprotein E gene polymorphisms in deep vein thrombosis patients: An Indian study. Phlebol. J. Venous Dis. 2018, 34, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frikke-Schmidt, R.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Steffensen, R.; Jensen, G.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Apolipoprotein E genotype: Epsilon32 women are protected while epsilon43 and epsilon44 men are susceptible to ischemic heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 35, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elosua, R.; Ordovas, J.M.; Cupples, L.A.; Fox, C.S.; Polak, J.F.; Wolf, P.A.; D’Agostino, R.A.; O’Donnell, C.J. Association of APOE genotype with carotid atherosclerosis in men and women. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 1868–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marz, W.; Scharnagl, H.; Hoffmann, M.; Boehm, B.; Winkelmann, B. The apolipoprotein E polymorphism is associated with circulating C-reactive protein (the Ludwigshafen risk and cardiovascular health study). Eur. Heart J. 2004, 25, 2109–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofler, B.M.; Miles, E.A.; Curtis, P.; Armah, C.K.; Tricon, S.; Grew, J.; Napper, F.L.; Farrell, L.; Lietz, G.; Packard, C.J.; et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and the cardiovascular disease risk phenotype: Impact of sex and adiposity (the FINGEN study). Atherosclerosis 2012, 221, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corella, D.; Tucker, K.; Lahoz, C.; Coltell, O.; Cupples, L.A.; Wilson, P.W.F.; Schaefer, E.J.; Ordovas, J.M. Alcohol drinking determines the effect of the APOE locus on LDL-cholesterol concentrations in men: The Framingham Offspring Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djoussé, L.; Myers, R.H.; Province, M.A.; Hunt, S.C.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Evans, G.; Peacock, J.M.; Ellison, R.C. Influence of Apolipoprotein E, Smoking, and Alcohol Intake on Carotid Atherosclerosis. Stroke 2002, 33, 1357–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueguen, R.; Visvikis, S.; Steinmetz, J.; Siest, G.; Boerwinkle, E. An analysis of genotype effects and their interactions by using the apolipoprotein E polymorphism and longitudinal data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1989, 45, 793–802. [Google Scholar]

- Marques-Vidal, P.; Bongard, V.; Ruidavets, J.B.; Fauvel, J.; Hanaire-Broutin, H.; Perret, B.; Ferrières, J. Obesity and Alcohol Modulate the Effect of Apolipoprotein E Polymorphism on Lipids and Insulin. Obes. Res. 2012, 11, 1200–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahley, R.W.; Huang, Y.; Rall, S.C. Pathogenesis of type III hyperlipoproteinemia (dysbetalipoproteinemia): Questions, quandaries, and paradoxes. J. Lipid Res. 1999, 40, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Eto, M.; Nitta, H.; Kanda, Y.; Shigeto, M.; Nakayama, K.; Tawaramoto, K.; Kawasaki, F.; Kamei, S.; Kohara, K.; et al. Effect of Apolipoprotein E4 Allele on Plasma LDL Cholesterol Response to Diet Therapy in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bernstein, M.S.; Costanza, M.C.; James, R.W.; Morris, M.A.; Cambien, F.O.; Raoux, S.G.N.; Morabia, A. Physical Activity May Modulate Effects of ApoE Genotype on Lipid Profile. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, P.F.; Fernhall, B. Physical Activity and High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels. Sports Med. 1999, 28, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade, F.M.; Bulhões, A.C.; Maluf, S.W.; Schuch, J.B.; Voigt, F.; Lucatelli, J.F.; Barros, A.C.; Hutz, M.H. The Influence of Nutrigenetics on the Lipid Profile: Interaction Between Genes and Dietary Habits. Biochem. Genet. 2010, 48, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virparia, R.; Brunetti, L.; Vigdor, S.; Adams, C.D. Appropriateness of thrombophilia testing in patients in the acute care setting and an evaluation of the associated costs. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2019, 49, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arachchillage, D.J.; Mackillop, L.; Chandratheva, A.; Motawani, J.; MacCallum, P.; Laffan, M. Thrombophilia testing: A British Society for Haematology guideline. Br. J. Haematol. 2022, 198, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hixson, J.E.; Vernier, D.T. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J. Lipid Res. 1990, 31, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligsohn, U.; Kornbrot, N.; Amit, Y.; Peretz, H.; Rosenberg, N.; Zivelin, A. Improved Method for Genotyping Apolipoprotein E Polymorphisms by a PCR-Based Assay Simultaneously Utilizing Two Distinct Restriction Enzymes. Clin. Chem. 1997, 43, 1657–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, J.R.; Kachman, M.T.; Killeen, A.A.; Akel, N.; Siemieniak, D.; Lubman, D.M. Genotyping of Apolipoprotein E by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1998, 12, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.-H.; Zha, G.-C.; Jiao, J.-W.; Yang, L.-Y.; Zhan, X.-F.; Chen, J.-T.; Xie, D.-D.; Eyi, U.M.; Matesa, R.A.; Obono, M.M.O.; et al. Rapid identification of apolipoprotein E genotypes by high-resolution melting analysis in Chinese Han and African Fang populations. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 9, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean Poulson, M.; Wittwer, C.T. Closed-tube genotyping of apolipoprotein E by isolated-probe PCR with multiple unlabeled probes and high-resolution DNA melting analysis. BioTechniques 2018, 43, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, W.; Ehrenhaft, A.; Griesser, K.; Pfeufer, A.; Müller, J.; Schömig, A.; Kastrati, A. TaqMan Systems for Genotyping of Disease-Related Polymorphisms Present in the Gene Encoding Apolipoprotein E. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2002, 40, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, O.; Hortigüela, R.; Bullido, M.J.; Calero, M. Apolipoprotein E genotyping method by Real Time PCR, a fast and cost-effective alternative to the TaqMan® and FRET assays. J. Neurosci. Methods 2009, 183, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, I.; Mooijaart, S.P.; Berbée, J.F.P.; van Heemst, D.; Havekes, L.M.; de Craen, A.J.M.; Slagboom, P.E.; Rensen, P.C.N.; Westendorp, R.G.J. ApoE Plasma Levels and Risk of Cardiovascular Mortality in Old Age. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, P.; Mooijaart, S.P.; De Craen, A.J.M.; Rensen, P.C.N.; Van Heemst, D.; Westendorp, R.G.J. Plasma Levels of Apolipoprotein E and Risk of Stroke in Old Age. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1100, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsetti, J.P.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Navis, G.; Sparks, C.E.; Dullaart, R.P.F. Apolipoprotein E predicts incident cardiovascular disease risk in women but not in men with concurrently high levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and C-reactive protein. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2012, 61, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, G.J.; Silvestri, G.; Chakravarthy, U.; Dasari, S.; Fritsche, L.G.; Weber, B.H.; Keilhauer, C.N.; Klein, M.L.; Francis, P.J.; Klaver, C.C.; et al. Variations in Apolipoprotein E Frequency with Age in a Pooled Analysis of a Large Group of Older People. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Trikalinos, T.A. Early extreme contradictory estimates may appear in published research: The Proteus phenomenon in molecular genetics research and randomized trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaster, M.W.; Shah, A.; Kangarlu, J.; Cheikhali, R.; Frishman, W.H.; Aronow, W.S. The Impact of the Apolipoprotein E Genotype on Cardiovascular Disease and Cognitive Disorders. Cardiol. Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, T.F.; Wenzl, F.A.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Friedman, P.A.; Antoniades, C. Artificial intelligence in cardiovascular medicine: Clinical applications. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 4291–4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marottoli, F.M.; Trevino, T.N.; Geng, X.; Arbieva, Z.; Kanabar, P.; Maienschein-Cline, M.; Lee, J.C.; Lutz, S.E.; Tai, L.M. Autocrine Effects of Brain Endothelial Cell-Produced Human Apolipoprotein E on Metabolism and Inflammation in vitro. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 668296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomarker | Origin/Mechanism | Physiological Role | Clinical Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitric Oxide (NO) | Generated by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) | Vasodilation; platelet aggregation inhibition; leukocyte adhesion reduction | Impaired eNOS or oxidative NO inactivation contributes to endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis | [54] |

| Endothelin-1 (ET-1) | Produced by endothelial cells | Potent vasoconstrictor; promotes vascular smooth muscle proliferation, oxidative stress, fibrosis | Chronic elevation leads to vascular remodeling and microvascular complications | [55] |

| von Willebrand Factor (vWF) | Stored in Weibel–Palade bodies of endothelial cells and platelet α-granules | Platelet adhesion | Elevated levels indicate endothelial damage | [56,57,58,59] |

| ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 | Upregulated by cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 | Leukocyte migration during inflammation | Key role in endothelial activation and inflammation | [60] |

| TNF-α | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | Increases oxidative stress; impairs eNOS; increases adhesion molecule expression | Drives endothelial oxidative stress, suppresses eNOS | [61,62] |

| IL-6 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | Induces acute-phase reactants; enhances platelet production and activation | Drives endothelial oxidative stress, suppresses eNOS | [61,62] |

| Component | Description/Mechanisms | Clinical Implications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ApoE Genotype | ε2: ↓LDL-C, ↑TG; partial protection but risk of dysbetalipoproteinemia. ε3: neutral, metabolic balance. ε4: ↑LDL-C, ↑oxidative stress, ↑VCAM-1 expression, endothelial dysfunction. | Genetic basis for lipid and endothelial alterations; ε4 carriers have increased CAD and stroke risk, ε2 carriers partial protection. | [6,47,53] |

| Endothelial Biomarkers | ↓NO bioavailability; ↑ET-1 vasoconstriction; fibrosis and vascular remodeling; ↑vWF, ICAM-1, VCAM-1; ↑IL-6, TNF-α; ↑oxidative stress and inflammation. | Reflect endothelial integrity; elevated levels indicate vascular dysfunction, inflammation, and thrombotic risk. | [54,55,60] |

| Interaction ApoE–Endothelium | ApoE deficiency → ↑ROS, ↑adhesion molecules, ↓NO signaling; ε4 allele amplifies oxidative and inflammatory endothelial responses | ε4 carriers show endothelial activation, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction. | [48,50] |

| Clinical Integration | Combined evaluation (ApoE genotype + endothelial biomarkers) for refined cardiovascular risk profiling | Avoids low-yield thrombophilia testing; identifies high-risk or borderline-risk patients | [63,86] |

| Precision Medicine Perspective | Integration of genetic and endothelial data enables individualized prevention and therapy | Personalized cardiovascular risk stratification; supports early detection and tailored management | [33,62] |

| Patient Group | ApoE Genotype of Interest | Risk Factors/Clinical Context | Clinical Utility | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals with unhealthy lifestyle (obesity, smoking, high alcohol intake) | ε4 carriers (ε2/ε4, ε3/ε4, ε4/ε4) | Increased vascular dysfunction, elevated triglycerides, LDL-C, β-lipoproteins, insulin | Identify high-risk individuals who may benefit from personalized monitoring and preventive strategies | [96,97,98,99] |

| Family history of type III dysbetalipoproteinemia | ε2/ε2 (homozygous) | Rare lipid disorder; early identification allows monitoring of secondary risk factors | Enable early intervention, risk factor control, and potentially delay/prevent disease onset | [100] |

| Patients with type 2 diabetes or dyslipidemia | ε4 carriers (ε2/ε4, ε3/ε4, ε4/ε4) | Altered response to diet and exercise; higher LDL-C and total cholesterol | Guide personalized dietary and lifestyle interventions to optimize lipid profile and cardiovascular risk | [101,102,103,104] |

| Patients undergoing thrombophilia testing with unclear benefit | Any genotype with endothelial biomarkers | Conventional thrombophilia tests often low-yield; unnecessary testing can increase cost and anxiety | Use genotyping combined with functional markers to reduce non-informative tests and focus preventive resources | [105,106] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Titolo, G.; Morello, M.; Caiazza, S.; Luisi, E.; Solimene, A.; Serpico, C.; D’Elia, S.; Golino, P.; Loffredo, F.S.; Natale, F.; et al. APOE Genotype and Endothelial Biomarkers: Towards Personalized Cardiovascular Screening. Genes 2025, 16, 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121494

Titolo G, Morello M, Caiazza S, Luisi E, Solimene A, Serpico C, D’Elia S, Golino P, Loffredo FS, Natale F, et al. APOE Genotype and Endothelial Biomarkers: Towards Personalized Cardiovascular Screening. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121494

Chicago/Turabian StyleTitolo, Gisella, Mariarosaria Morello, Silvia Caiazza, Ettore Luisi, Achille Solimene, Chiara Serpico, Saverio D’Elia, Paolo Golino, Francesco S. Loffredo, Francesco Natale, and et al. 2025. "APOE Genotype and Endothelial Biomarkers: Towards Personalized Cardiovascular Screening" Genes 16, no. 12: 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121494

APA StyleTitolo, G., Morello, M., Caiazza, S., Luisi, E., Solimene, A., Serpico, C., D’Elia, S., Golino, P., Loffredo, F. S., Natale, F., & Cimmino, G. (2025). APOE Genotype and Endothelial Biomarkers: Towards Personalized Cardiovascular Screening. Genes, 16(12), 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121494