WES-Based Screening of a Swedish Patient Series with Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Genetic and Bioinformatic Analyses

2.3. PD Patients in the MDCS Cohort

3. Results

3.1. Known Pathogenic Variants in Established PD Genes

3.2. CHCHD2 p.(Phe84LeufsTer6)

3.3. Overall Diagnostic Yield for Monogenic PD

3.4. GBA1 Risk Variants

3.5. Heterozygous ATP7B Variants

3.6. Variants in ARSA

3.7. Additional Variants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, F.; Fellner, A.; Kumar, K.R. Monogenic Parkinson’s Disease: Genotype, Phenotype, Pathophysiology, and Genetic Testing. Genes 2022, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Schapira, A.H.V. GBA Variants and Parkinson Disease: Mechanisms and Treatments. Cells 2022, 11, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, E.; Landoulsi, Z.; Pachchek, S.; Consortium, N.-P.; Krawitz, P.; Maj, C.; Kruger, R.; May, P.; Bobbili, D.R. Penetrance of Parkinson’s disease in GBA1 carriers depends on variant severity and polygenic background. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorcenco, S.; Ilinca, A.; Almasoudi, W.; Kafantari, E.; Lindgren, A.G.; Puschmann, A. New generation genetic testing entering the clinic. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 73, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ygland Rodstrom, E.; Puschmann, A. Clinical classification systems and long-term outcome in mid- and late-stage Parkinson’s disease. npj Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brolin, K.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Blauwendraat, C.; Widner, H.; Odin, P.; Hansson, O.; Puschmann, A.; Swanberg, M. Insights on Genetic and Environmental Factors in Parkinson’s Disease from a Regional Swedish Case-Control Cohort. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astrom, D.O.; Simonsen, J.; Raket, L.L.; Sgarbi, S.; Hellsten, J.; Hagell, P.; Norlin, J.M.; Kellerborg, K.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Odin, P. High risk of developing dementia in Parkinson’s disease: A Swedish registry-based study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Auwera, G.A.; Carneiro, M.O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; Del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J.; et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2013, 43, 11.10.1–11.10.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2987–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, W.; Gil, L.; Hunt, S.E.; Riat, H.S.; Ritchie, G.R.; Thormann, A.; Flicek, P.; Cunningham, F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Francioli, L.C.; Goodrich, J.K.; Collins, R.L.; Kanai, M.; Wang, Q.; Alfoldi, J.; Watts, N.A.; Vittal, C.; Gauthier, L.D.; et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature 2024, 625, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genomes Project, C.; Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A.; et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Jian, X.; Boerwinkle, E. dbNSFP: A lightweight database of human nonsynonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Hum. Mutat. 2011, 32, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, C.; Mou, C.; Dong, Y.; Tu, Y. dbNSFP v4: A comprehensive database of transcript-specific functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, K.; Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou, S.; McRae, J.F.; Darbandi, S.F.; Knowles, D.; Li, Y.I.; Kosmicki, J.A.; Arbelaez, J.; Cui, W.; Schwartz, G.B.; et al. Predicting Splicing from Primary Sequence with Deep Learning. Cell 2019, 176, 535–548.e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubach, M.; Maass, T.; Nazaretyan, L.; Roner, S.; Kircher, M. CADD v1.7: Using protein language models, regulatory CNNs and other nucleotide-level scores to improve genome-wide variant predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1143–D1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Riley, G.R.; Jang, W.; Rubinstein, W.S.; Church, D.M.; Maglott, D.R. ClinVar: Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D980–D985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanos, C.; Tsiolkas, V.; Kouris, A.; Chapple, C.E.; Albarca Aguilera, M.; Meyer, R.; Massouras, A. VarSome: The human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1978–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plagnol, V.; Curtis, J.; Epstein, M.; Mok, K.Y.; Stebbings, E.; Grigoriadou, S.; Wood, N.W.; Hambleton, S.; Burns, S.O.; Thrasher, A.J.; et al. A robust model for read count data in exome sequencing experiments and implications for copy number variant calling. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2747–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.T.; Thorvaldsdottir, H.; Winckler, W.; Guttman, M.; Lander, E.S.; Getz, G.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, W.J. BLAT—The BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Forer, L.; Schonherr, S.; Sidore, C.; Locke, A.E.; Kwong, A.; Vrieze, S.I.; Chew, E.Y.; Levy, S.; McGue, M.; et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1284–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, S.; Das, S.; Kretzschmar, W.; Delaneau, O.; Wood, A.R.; Teumer, A.; Kang, H.M.; Fuchsberger, C.; Danecek, P.; Sharp, K.; et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1279–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Browning, S.R.; Browning, B.L. A Fast and Simple Method for Detecting Identity-by-Descent Segments in Large-Scale Data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 106, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manderstedt, E.; Lind-Hallden, C.; Hallden, C.; Elf, J.; Svensson, P.J.; Dahlback, B.; Engstrom, G.; Melander, O.; Baras, A.; Lotta, L.A.; et al. Classic Thrombophilias and Thrombotic Risk Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschmann, A.; Ross, O.A.; Vilarino-Guell, C.; Lincoln, S.J.; Kachergus, J.M.; Cobb, S.A.; Lindquist, S.G.; Nielsen, J.E.; Wszolek, Z.K.; Farrer, M.; et al. A Swedish family with de novo alpha-synuclein A53T mutation: Evidence for early cortical dysfunction. Park. Relat. Disord. 2009, 15, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, J.; Nilsson, C.; Kachergus, J.; Munz, M.; Larsson, E.M.; Schule, B.; Langston, J.W.; Middleton, F.A.; Ross, O.A.; Hulihan, M.; et al. Phenotypic variation in a large Swedish pedigree due to SNCA duplication and triplication. Neurology 2007, 68, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlar, S.C.; Grenn, F.P.; Kim, J.J.; Baluwendraat, C.; Gan-Or, Z. Classification of GBA1 Variants in Parkinson’s Disease: The GBA1-PD Browser. Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brolin, K.A.; Backstrom, D.; Wallenius, J.; Gan-Or, Z.; Puschmann, A.; Hansson, O.; Swanberg, M. GBA1 T369M and Parkinson’s disease—Further evidence of a lack of association in the Swedish population. Park. Relat. Disord. 2025, 130, 107191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, E.; Thornqvist, M.; Holmberg, B.; Machaczka, M.; Sidransky, E.; Svenningsson, P. First Clinicogenetic Description of Parkinson’s Disease Related to GBA Mutation S107L. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2019, 6, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbert, C.; Schaake, S.; Luth, T.; Much, C.; Klein, C.; Aasly, J.O.; Farrer, M.J.; Trinh, J. GBA1 in Parkinson’s disease: Variant detection and pathogenicity scoring matters. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotakaki, E.; Tzetis, M.; Manolaki, N.; Loudianos, G.; Papatheodorou, A.; Manesis, E.; Nousia-Arvanitakis, S.; Syriopoulou, V.; Kanavakis, E. Genotype-phenotype correlations for a wide spectrum of mutations in the Wilson disease gene (ATP7B). Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2004, 131, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D.W.; Prat, L.; Walshe, J.M.; Heathcote, J.; Gaffney, D. Twenty-four novel mutations in Wilson disease patients of predominantly European ancestry. Hum. Mutat. 2005, 26, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puschmann, A.; Jimenez-Ferrer, I.; Lundblad-Andersson, E.; Martensson, E.; Hansson, O.; Odin, P.; Widner, H.; Brolin, K.; Mzezewa, R.; Kristensen, J.; et al. Low prevalence of known pathogenic mutations in dominant PD genes: A Swedish multicenter study. Park. Relat. Disord. 2019, 66, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, L.; Verbrugge, J.; Schwantes-An, T.H.; Schulze, J.; Foroud, T.; Hall, A.; Marder, K.S.; Mata, I.F.; Mencacci, N.E.; Nance, M.A.; et al. Parkinson’s disease variant detection and disclosure: PD GENEration, a North American study. Brain 2024, 147, 2668–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towns, C.; Fang, Z.H.; Tan, M.M.X.; Jasaityte, S.; Schmaderer, T.M.; Stafford, E.J.; Pollard, M.; Tilney, R.; Hodgson, M.; Wu, L.; et al. Parkinson’s families project: A UK-wide study of early onset and familial Parkinson’s disease. npj Park. Dis. 2024, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymeropoulos, M.H.; Lavedan, C.; Leroy, E.; Ide, S.E.; Dehejia, A.; Dutra, A.; Pike, B.; Root, H.; Rubenstein, J.; Boyer, R.; et al. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science 1997, 276, 2045–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Sun, Y.; Song, Z.; Zheng, W.; Xiong, W.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, L.; Deng, H. Genetic Analysis and Literature Review of SNCA Variants in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 648151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, T.; Ross, O.A.; Puschmann, A.; Dickson, D.W.; Wszolek, Z.K. Autosomal dominant Parkinson’s disease caused by SNCA duplications. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 22 (Suppl. S1), S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, A.B.; Farrer, M.; Johnson, J.; Singleton, A.; Hague, S.; Kachergus, J.; Hulihan, M.; Peuralinna, T.; Dutra, A.; Nussbaum, R.; et al. Alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science 2003, 302, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Book, A.; Guella, I.; Candido, T.; Brice, A.; Hattori, N.; Jeon, B.; Farrer, M.J. the SNCA Multiplication Investigators of the GEoPD Consortium. A Meta-Analysis of alpha-Synuclein Multiplication in Familial Parkinsonism. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C.; Vinikoor-Imler, L.; Nassan, F.L.; Shirvan, J.; Lally, C.; Dam, T.; Maserejian, N. Prevalence of ten LRRK2 variants in Parkinson’s disease: A comprehensive review. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 98, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmine Belin, A.; Westerlund, M.; Sydow, O.; Lundstromer, K.; Hakansson, A.; Nissbrandt, H.; Olson, L.; Galter, D. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) mutations in a Swedish Parkinson cohort and a healthy nonagenarian. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 1731–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowlands, J.; Moore, D.J. VPS35 and retromer dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2024, 379, 20220384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilarino-Guell, C.; Wider, C.; Ross, O.A.; Dachsel, J.C.; Kachergus, J.M.; Lincoln, S.J.; Soto-Ortolaza, A.I.; Cobb, S.A.; Wilhoite, G.J.; Bacon, J.A.; et al. VPS35 mutations in Parkinson disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimprich, A.; Benet-Pages, A.; Struhal, W.; Graf, E.; Eck, S.H.; Offman, M.N.; Haubenberger, D.; Spielberger, S.; Schulte, E.C.; Lichtner, P.; et al. A mutation in VPS35, encoding a subunit of the retromer complex, causes late-onset Parkinson disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.T.; Chen, X.; Moore, D.J. VPS35, the Retromer Complex and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2017, 7, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, C.D.; Witherspoon, D.J.; Simonson, T.S.; Xing, J.; Watkins, W.S.; Zhang, Y.; Tuohy, T.M.; Neklason, D.W.; Burt, R.W.; Guthery, S.L.; et al. Maximum-likelihood estimation of recent shared ancestry (ERSA). Genome Res. 2011, 21, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, T.R.; Espinoza Gonzalez, P.; Wehinger, J.L.; Bukhari, M.Z.; Ermekbaeva, A.; Sista, A.; Kotsiviras, P.; Liu, T.; Kang, D.E.; Woo, J.A. Mitochondrial CHCHD2: Disease-Associated Mutations, Physiological Functions, and Current Animal Models. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 660843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funayama, M.; Ohe, K.; Amo, T.; Furuya, N.; Yamaguchi, J.; Saiki, S.; Li, Y.; Ogaki, K.; Ando, M.; Yoshino, H.; et al. CHCHD2 mutations in autosomal dominant late-onset Parkinson’s disease: A genome-wide linkage and sequencing study. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.G.; Sedghi, M.; Salari, M.; Shearwood, A.J.; Stentenbach, M.; Kariminejad, A.; Goullee, H.; Rackham, O.; Laing, N.G.; Tajsharghi, H.; et al. Early-onset Parkinson disease caused by a mutation in CHCHD2 and mitochondrial dysfunction. Neurol. Genet. 2018, 4, e276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koschmidder, E.; Weissbach, A.; Bruggemann, N.; Kasten, M.; Klein, C.; Lohmann, K. A nonsense mutation in CHCHD2 in a patient with Parkinson disease. Neurology 2016, 86, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Li, L.; Ren, J.; Guo, J.; Tang, B.; Liu, W. Genetic Analysis of Patients with Early-Onset Parkinson’s Disease in Eastern China. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 849462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P.; Yu, S.H.; Zhang, G.H.; Hou, Y.B.; Gu, X.J.; Ou, R.W.; Shen, Y.; Song, W.; Chen, X.P.; Zhao, B.; et al. The mutation spectrum of Parkinson-disease-related genes in early-onset Parkinson’s disease in ethnic Chinese. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 3218–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, A.; Nishioka, K.; Meng, H.; Takanashi, M.; Hasegawa, I.; Inoshita, T.; Shiba-Fukushima, K.; Li, Y.; Yoshino, H.; Mori, A.; et al. Mutations in CHCHD2 cause alpha-synuclein aggregation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 3895–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westenberger, A.; Skrahina, V.; Usnich, T.; Beetz, C.; Vollstedt, E.J.; Laabs, B.H.; Paul, J.J.; Curado, F.; Skobalj, S.; Gaber, H.; et al. Relevance of genetic testing in the gene-targeted trial era: The Rostock Parkinson’s disease study. Brain 2024, 147, 2652–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, C.; Brodin, L.; Gellhaar, S.; Westerlund, M.; Fardell, C.; Nissbrandt, H.; Soderkvist, P.; Sydow, O.; Markaki, I.; Hertz, E.; et al. Glucocerebrosidase variant T369M is not a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease in Sweden. Neurosci. Lett. 2022, 784, 136767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, C.; Brodin, L.; Forsgren, L.; Westerlund, M.; Ramezani, M.; Gellhaar, S.; Xiang, F.; Fardell, C.; Nissbrandt, H.; Soderkvist, P.; et al. Strong association between glucocerebrosidase mutations and Parkinson’s disease in Sweden. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 45, 212.e5–212.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, N.; Hillborg, P.O.; Olofsson, A. Gaucher disease (Norrbottnian type III): Probable founders identified by genealogical and molecular studies. Hum. Genet. 1993, 92, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinderi, K.; Bostantjopoulou, S.; Paisan-Ruiz, C.; Katsarou, Z.; Hardy, J.; Fidani, L. Complete screening for glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson disease patients from Greece. Neurosci. Lett. 2009, 452, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Kanai, K.; Suzuki, M.; Kim, W.S.; Yoo, H.S.; Fu, Y.; Kim, D.K.; Jung, B.C.; Choi, M.; Oh, K.W.; et al. Arylsulfatase A, a genetic modifier of Parkinson’s disease, is an alpha-synuclein chaperone. Brain 2019, 142, 2845–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarious, M.B.; Lake, J.; Pitz, V.; Ye Fu, A.; Guidubaldi, J.L.; Solsberg, C.W.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Leonard, H.L.; Kim, J.J.; Billingsley, K.J.; et al. Large-scale rare variant burden testing in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2023, 146, 4622–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkevich, K.; Beletskaia, M.; Dworkind, A.; Yu, E.; Ahmad, J.; Ruskey, J.A.; Asayesh, F.; Spiegelman, D.; Fahn, S.; Waters, C.; et al. Association of Rare Variants in ARSA with Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 1806–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyechova, E.Y.; Miliukhina, I.V.; Karpenko, M.N.; Orlov, I.A.; Puchkova, L.V.; Samsonov, S.A. Case of Early-Onset Parkinson’s Disease in a Heterozygous Mutation Carrier of the ATP7B Gene. J. Pers. Med. 2019, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo Rueda, M.P.; Raftopoulou, A.; Gogele, M.; Borsche, M.; Emmert, D.; Fuchsberger, C.; Hantikainen, E.M.; Vukovic, V.; Klein, C.; Pramstaller, P.P.; et al. Frequency of Heterozygous Parkin (PRKN) Variants and Penetrance of Parkinson’s Disease Risk Markers in the Population-Based CHRIS Cohort. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 706145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbe, S.J.; Bustos, B.I.; Hu, J.; Krainc, D.; Joseph, T.; Hehir, J.; Tan, M.; Zhang, W.; Escott-Price, V.; Williams, N.M.; et al. Assessing the relationship between monoallelic PRKN mutations and Parkinson’s risk. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanou, M.I.; Katsaros, V.K.; Pepe, G.; Theodorou, A.; Stefanou, D.; Koropouli, E.; Paraskevas, G.P.; Tsivgoulis, G. Early-Onset Parkinson’s Disease in a Patient with a De Novo Frameshift Variant of the ANKRD11 Gene and KBG Syndrome. J. Clin. Neurol. 2025, 21, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencacci, N.E.; Minakaki, G.; Maroofian, R.; De Pace, R.; Paimboeuf, A.; Shannon, P.; Chitayat, D.; Magrinelli, F.; Peng, W.J.; Chatterjee, D.; et al. Pathogenic variants in BORCS5 Cause a Spectrum of Neurodevelopmental and Neurodegenerative Disorders with Lysosomal Dysfunction. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, N.; Dong, J.; Tian, W.; Chang, L.; Ma, J.; Guo, J.; Tan, J.; Dong, A.; He, K.; et al. Deficiency in endocannabinoid synthase DAGLB contributes to early onset Parkinsonism and murine nigral dopaminergic neuron dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.Y.; Tang, F.L.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, H.X.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Y.W.; He, R.C.; Zeng, S.; Wang, J.P.; Lin, W.; et al. Biallelic Variants in EPG5 Gene Are Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2025, 98, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuladottir, A.T.; Tragante, V.; Sveinbjornsson, G.; Helgason, H.; Sturluson, A.; Bjornsdottir, A.; Jonsson, P.; Palmadottir, V.; Sveinsson, O.A.; Jensson, B.O.; et al. Loss-of-function variants in ITSN1 confer high risk of Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2024, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magrinelli, F.; Tesson, C.; Angelova, P.R.; Salazar-Villacorta, A.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Scardamaglia, A.; Chung, B.H.; Jaconelli, M.; Vona, B.; Esteras, N.; et al. PSMF1 variants cause a phenotypic spectrum from early-onset Parkinson’s disease to perinatal lethality by disrupting mitochondrial pathways. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, D.J.S.; Carr, J.; Bardien, S.; Thomas, P.; Sebate, B.; Breedveld, G.J.; van Minkelen, R.; Brouwer, R.W.W.; van Ijcken, W.F.J.; van Slegtenhorst, M.A.; et al. PTRHD1 Loss-of-function mutation in an african family with juvenile-onset Parkinsonism and intellectual disability. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 1814–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, E.K.; Follett, J.; Trinh, J.; Barodia, S.K.; Real, R.; Liu, Z.; Grant-Peters, M.; Fox, J.D.; Appel-Cresswell, S.; Stoessl, A.J.; et al. RAB32 Ser71Arg in autosomal dominant Parkinson’s disease: Linkage, association, and functional analyses. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percetti, M.; Franco, G.; Monfrini, E.; Caporali, L.; Minardi, R.; La Morgia, C.; Valentino, M.L.; Liguori, R.; Palmieri, I.; Ottaviani, D.; et al. TWNK in Parkinson’s Disease: A Movement Disorder and Mitochondrial Disease Center Perspective Study. Mov. Disord. 2022, 37, 1938–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Study Population (PARLU and MPBC Studies Combined): | |

| Number of probands | 285 |

| Females/males | 61%:39% |

| Age at symptom onset (mean ± SD; range) | 56.1 (±16.1; 20–82) years |

| Age at study inclusion/last clinical follow-up (mean ± SD) | 65.5 (±11.4) years |

| Positive family history (any family member had PD) | 173 (60.8%) |

| Early onset (at or before age 50) | 91 (31.9%) |

| Mean (median; range) age of onset among the 91 patients with early onset | 43.2 (45; 20–50) years |

| Composition of PARLU and MPBC studies: | |

| PARLU study | Number of probands (with positive family history) |

| Total | 154 (95) |

| ≤30 years of age at symptom onset | 1 (1) |

| >30 and ≤40 years of age at symptom onset | 5 (0) |

| >40 and ≤50 years of age at symptom onset | 20 (10) |

| >50 years of age at symptom onset | 116 (78) |

| unknown age at symptom onset | 12 (6) |

| MPBC study | Number of probands (with positive family history) |

| Total | 131 (78) |

| ≤30 years of age at symptom onset | 2 (1) |

| >30 and ≤40 years of age at symptom onset | 18 (1) |

| >40 and ≤50 years of age at symptom onset | 45 (10) |

| >50 years of age at symptom onset | 54 (54) |

| unknown age at symptom onset | 12 (12) |

| Proband ID (Sex) | Age at Onset (Years) | Positive Family History | Phenomenology | Variant(s) Identified | ClinVar Entries (ID #), CADD-Phred Score, ACMG Classification | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P038 (F) | 39–41 | Yes | Parkinsonism, cognitive decline, language deficits, dysautonomia PMID: 19632874 | SNCA c.157G>A p.(Ala53Thr) het | P (14007), 15.7, P (PS4, PP1, PS3, PM1, PP2, PM2, PM5) | Disease-causing, known pathogenic variant. |

| P221 (F) | 43 | Yes | Parkinsonism, rigidity, bradykinesia in left side | LRRK2 c.6055G>A p.(Gly2019Ser) het | P/LP; risk factor (1940), 31, P (PS4, PP3, PM2) | Disease-causing, known pathogenic variant. |

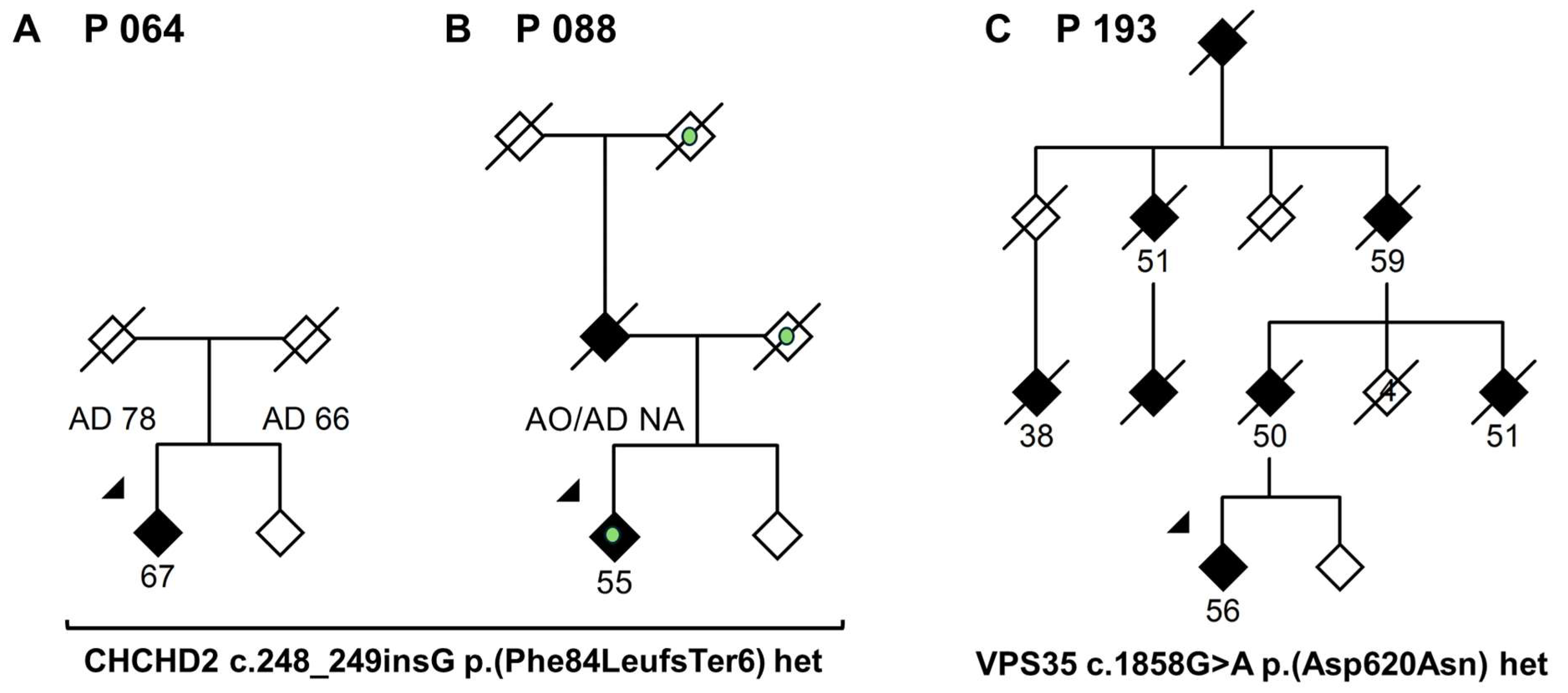

| P193 (F) | 56 | Yes | Parkinsonism. Marked family history for PD and cognitive decline, average AAO in family: 50.8 years | VPS35 c.1858G>A p.(Asp620Asn) het | Not reported, 31, LP (PS4, PP1, PM2, PP2) | Disease-causing, known pathogenic variant. |

| P064 (M) | 67 | No | Parkinsonism, tremor, dystonic signs (see main text) | CHCHD2 c.248_249insG p.(Phe84LeufsTer6) het | Not reported, 32, LP (PVS1, PM2) | Likely disease-causing, novel variant. |

| P088 (F) | 57 | Yes | Parkinsonism, tremor, dystonic signs, dementia (see main text) | CHCHD2 c.248_249insG p.(Phe84LeufsTer6) het | Not reported, 32, LP (PVS1, PM2) | Likely disease-causing, novel variant. |

| P182(F) | 51 | Yes | Cognitive dysfunction, Parkinsonism, dysautonomia. Unilateral upper limb spasticity in advanced disease | SNCA ExomeDepth [GRCh38] (chr4:89724100-89954614)x3 arr [GRCh37] 4q22.1(90320154_91139340)x3 | Not reported | Disease-causing, known pathogenic variant |

| Variant(s) Identified gnomAD Frequency NFE | Occurrence in This Study Number of Carriers from Among 285 Probands with PD * | Occurrence in MDCS Population DatabaseNumber of Carriers from Among 695 PD Patients and 25,684 Controls * | Chi-Squared p-Value, One-Sided Fisher’s Exact Test p-Value, OR (95% CI), of All Individuals Combined |

| CHCHD2 c.248_249insG p.(Phe84LeufsTer6) het 0.000001695 | 2 | 0 PD, 2 controls | p: 0.00000086 (0.00032 Yates-corrected), p: 0.0077, OR: 26.23 (3.69–186) |

| ARSA c.386G>C p.(Gly129Ala) het | 1 | 0 PD, 0 controls | p: 0.00000031 (0.013 Yates-corrected), p: 0.037, OR: 78.58 (3.19–1930) |

| ARSA c.465 + 1 G>A het 0.001030 | 2 | 3 PD, 81 controls § | p: 0.29 (0.44 Yates-corrected), p: 0.21, OR: 1.61 (0.65–4.00) |

| ARSA c.902G>A p.(Arg301Gln) het 0.00001441 | 1 | 0 PD, 13 controls | p: 0.49 (1.0 Yates-corrected), p: 0.41, OR: 2.01 (0.26–15.41) |

| ARSA c.1051C>G p.(Pro351Ala) het 0.000 | 1 | 0 PD, 6 controls | p: 0.13 (0.62 Yates-corrected), p: 0.23, OR: 4.36 (0.52–36.30) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kafantari, E.; Atterling Brolin, K.; Wallenius, J.; Swanberg, M.; Puschmann, A. WES-Based Screening of a Swedish Patient Series with Parkinson’s Disease. Genes 2025, 16, 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121482

Kafantari E, Atterling Brolin K, Wallenius J, Swanberg M, Puschmann A. WES-Based Screening of a Swedish Patient Series with Parkinson’s Disease. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121482

Chicago/Turabian StyleKafantari, Efthymia, Kajsa Atterling Brolin, Joel Wallenius, Maria Swanberg, and Andreas Puschmann. 2025. "WES-Based Screening of a Swedish Patient Series with Parkinson’s Disease" Genes 16, no. 12: 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121482

APA StyleKafantari, E., Atterling Brolin, K., Wallenius, J., Swanberg, M., & Puschmann, A. (2025). WES-Based Screening of a Swedish Patient Series with Parkinson’s Disease. Genes, 16(12), 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121482