Common Ancestry from Southern Italy: Two Families with Dilated Cardiomyopathy Share the Same Homozygous Loss-of-Function Variant in NRAP

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Evaluation

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Exome Sequencing

2.4. Segregation Analysis

2.5. Kinship Estimation

2.6. Genealogy Investigation

3. Results

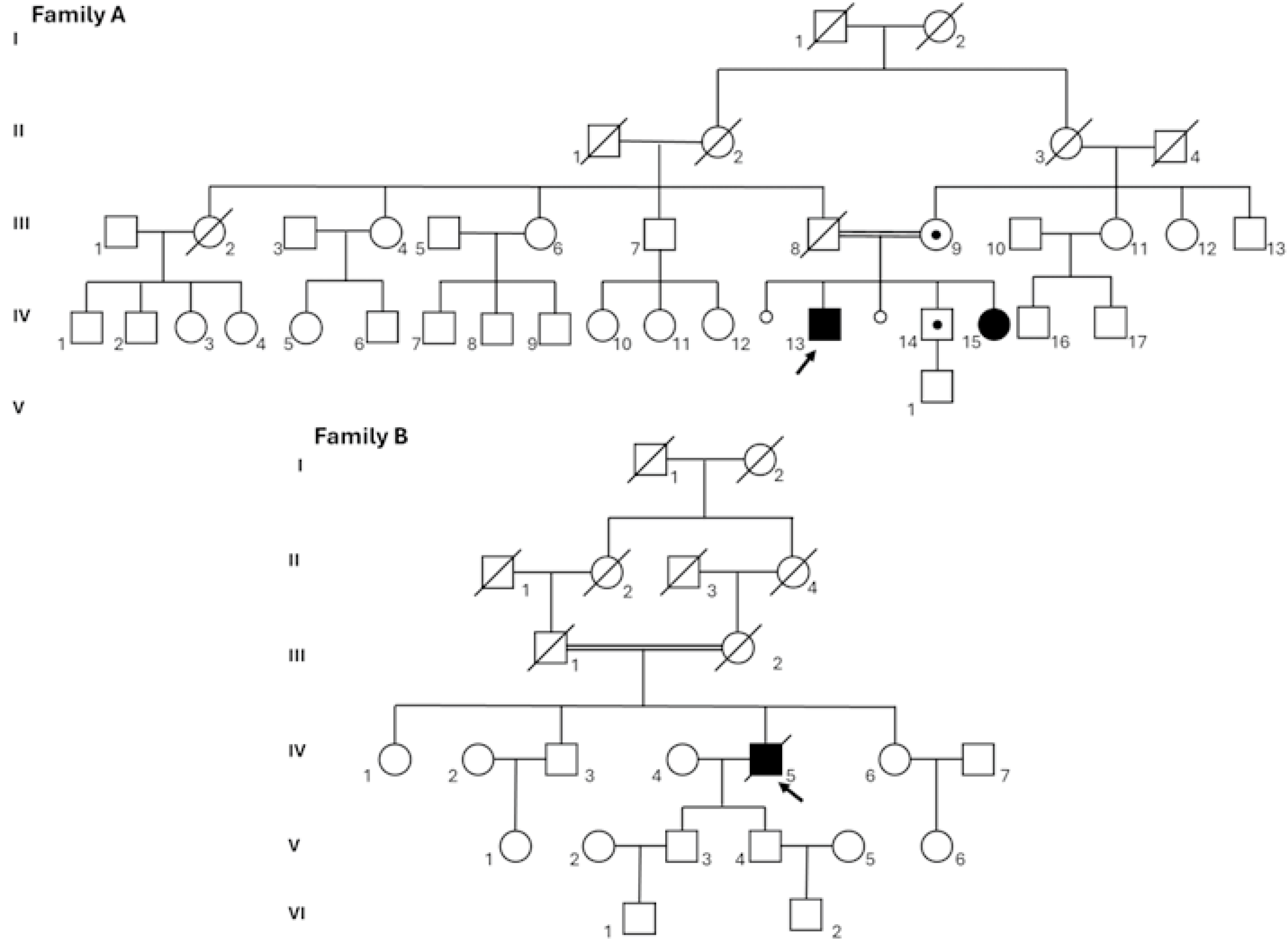

3.1. Case Presentation

3.1.1. Family A

3.1.2. Family B

3.2. Molecular Diagnosis

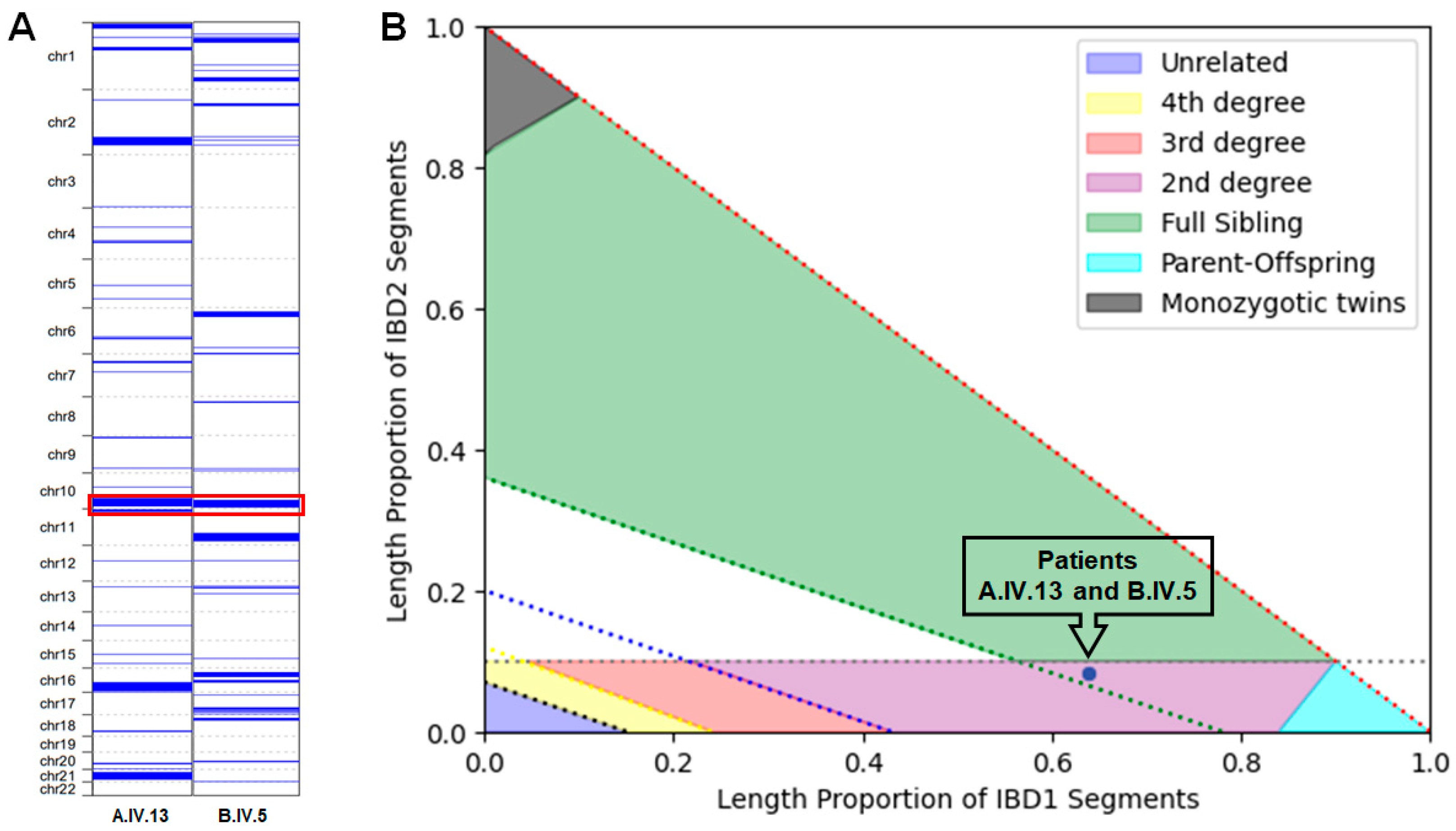

3.3. ROHs and Kinship Estimation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LoF | Loss-of-function |

| NRAP | Nebulin-related anchoring protein |

| DCM | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| NDLVC | Non-dilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| ARVC | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| RCM | Restrictive cardiomyopathy |

| LVNC | Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy |

| LASP-1 | LIM and SH3 Protein 1 |

| LASP-2 | LIM and SH3 Protein 2 |

| KLHL41 | Kelch-like family member 41 |

| CSRP3 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 3 |

| MLP | Muscle LIM protein |

| GATK | Genome Analysis Toolkit |

| VEP | Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor |

| ACMG | American College of Medical genetics |

| HGVS | Human genome variation society |

| ROH | Runs of homozygosity |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| LBBB | Left bundle branch block |

| NSVT | Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia |

| NT-proBNP | Type-B natriuretic peptide |

| IBS | Identity-by-state |

| LVAD | Left Ventricular Assist Device |

References

- Arbelo, E.; Protonotarios, A.; Gimeno, J.R.; Arbustini, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Basso, C.; Bezzina, C.R.; Biagini, E.; Blom, N.A.; de Boer, R.A.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3503–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Pereira, N.L. Genetics of Cardiomyopathy: Clinical and Mechanistic Implications for Heart Failure. Korean Circ. J. 2021, 51, 797–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrahman Ahmed, H.; Al-ghamdi, S.; Al Mutairi, F. Dilated cardiomyopathy in a child with truncating mutation in NRAP gene. JBC Genet. 2018, 30, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monies, D.; Abouelhoda, M.; AlSayed, M.; Alhassnan, Z.; Alotaibi, M.; Kayyali, H.; Al-Owain, M.; Shah, A.; Rahbeeni, Z.; Al-Muhaizea, M.A.; et al. The landscape of genetic diseases in Saudi Arabia based on the first 1000 diagnostic panels and exomes. Hum. Genet. 2017, 136, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truszkowska, G.T.; Bilinska, Z.T.; Muchowicz, A.; Pollak, A.; Biernacka, A.; Kozar-Kaminska, K.; Stawinski, P.; Gasperowicz, P.; Kosinska, J.; Zielinski, T.; et al. Homozygous truncating mutation in NRAP gene identified by whole exome sequencing in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilescu, C.; Ojala, T.H.; Brilhante, V.; Ojanen, S.; Hinterding, H.M.; Palin, E.; Alastalo, T.P.; Koskenvuo, J.; Hiippala, A.; Jokinen, E.; et al. Genetic Basis of Severe Childhood-Onset Cardiomyopathies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2324–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskenvuo, J.W.; Saarinen, I.; Ahonen, S.; Tommiska, J.; Weckstrom, S.; Seppala, E.H.; Tuupanen, S.; Kangas-Kontio, T.; Schleit, J.; Helio, K.; et al. Biallelic loss-of-function in NRAP is a cause of recessive dilated cardiomyopathy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, C.; Boleti, O.; Najarzadeh Torbati, P.; Norouzi, F.; Fowler, A.N.R.; Minaee, S.; Salih, K.H.; Taherpour, M.; Birjandi, H.; Alizadeh, B.; et al. Genetic Insights from Consanguineous Cardiomyopathy Families. Genes 2023, 14, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, K.; Ji, L.; Zhang, H.; Yin, J.; Zhou, M.; Wang, C.; Yang, S. A novel loss-of-function mutation in NRAP is associated with left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1097957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mio, C.; Zucco, J.; Fabbro, D.; Bregant, E.; Baldan, F.; Allegri, L.; D’Elia, A.V.; Collini, V.; Imazio, M.; Damante, G.; et al. The impact of the European Society of Cardiology guidelines and whole exome sequencing on genetic testing in hereditary cardiac diseases. Clin. Genet. 2024, 106, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, A.; Tulbah, S.; Alruwaili, N.; Takroni, S.; Alkorashy, M.; Manea, W.; Albert Brotons, D.C.; Alwadai, A.; Alburaiki, J.; Alkuraya, F.; et al. Reduced Penetrance and Variable Expression of Dilated Cardiomyopathy Associated With Homozygous Truncating Variants in NRAP Gene. Clin. Genet. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hassnan, Z.N.; Almesned, A.; Tulbah, S.; Alakhfash, A.; Alhadeq, F.; Alruwaili, N.; Alkorashy, M.; Alhashem, A.; Alrashdan, A.; Faqeih, E.; et al. Categorized Genetic Analysis in Childhood-Onset Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, C.T.; Bliss, K.T.; Zieseniss, A.; Gregorio, C.C. The Nebulin family: An actin support group. Trends Cell Biol. 2011, 21, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, M.L.; Chen, J. Roles of Nebulin Family Members in the Heart. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 2081–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labeit, S.; Gibson, T.; Lakey, A.; Leonard, K.; Zeviani, M.; Knight, P.; Wardale, J.; Trinick, J. Evidence that nebulin is a protein-ruler in muscle thin filaments. FEBS Lett. 1991, 282, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Knipfer, M.; Huang, Q.Q.; van Heerden, A.; Hsu, L.C.; Gutierrez, G.; Quian, X.L.; Stedman, H. Human skeletal muscle nebulin sequence encodes a blueprint for thin filament architecture. Sequence motifs and affinity profiles of tandem repeats and terminal SH3. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 4304–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiddin, S.A.; Lu, S.; Cardoso, J.P.; Carroll, S.; Jha, S.; Horowits, R.; Fananapazir, L. Genomic organization, alternative splicing, and expression of human and mouse N-RAP, a nebulin-related LIM protein of striated muscle. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2003, 55, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Herrera, A.H.; Horowits, R. Molecular interactions of N-RAP, a nebulin-related protein of striated muscle myotendon junctions and intercalated disks. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 6135–6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Carroll, S.L.; Herrera, A.H.; Ozanne, B.; Horowits, R. New N-RAP-binding partners alpha-actinin, filamin and Krp1 detected by yeast two-hybrid screening: Implications for myofibril assembly. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 2169–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Borst, D.E.; Horowits, R. Expression and alternative splicing of N-RAP during mouse skeletal muscle development. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2008, 65, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelin, K.; Hilpela, P.; Donner, K.; Sewry, C.; Akkari, P.A.; Wilton, S.D.; Wattanasirichaigoon, D.; Bang, M.L.; Centner, T.; Hanefeld, F.; et al. Mutations in the nebulin gene associated with autosomal recessive nemaline myopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 2305–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold-Zadok, M.; Chitayat, D.; Chong, K.; Injeyan, M.; Shannon, P.; Chapmann, D.; Maymon, R.; Pillar, N.; Reish, O. Mutations in the NEB gene cause fetal akinesia/arthrogryposis multiplex congenita. Prenat. Diagn. 2017, 37, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsenko, S.A.; Yatsenko, A.N.; Szigeti, K.; Craigen, W.J.; Stankiewicz, P.; Cheung, S.W.; Lupski, J.R. Interstitial deletion of 10p and atrial septal defect in DiGeorge 2 syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2004, 66, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ausubel, F.M.; Brent, R.; Kingston, R.E.; Moore, D.D.; Seidman, J.G.; Smith, J.A.; Struhl, K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, W.; Gil, L.; Hunt, S.E.; Riat, H.S.; Ritchie, G.R.; Thormann, A.; Flicek, P.; Cunningham, F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Dunnen, J.T.; Dalgleish, R.; Maglott, D.R.; Hart, R.K.; Greenblatt, M.S.; McGowan-Jordan, J.; Roux, A.F.; Smith, T.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Taschner, P.E. HGVS Recommendations for the Description of Sequence Variants: 2016 Update. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 37, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinodoz, M.; Peter, V.G.; Bedoni, N.; Royer Bertrand, B.; Cisarova, K.; Salmaninejad, A.; Sepahi, N.; Rodrigues, R.; Piran, M.; Mojarrad, M.; et al. AutoMap is a high performance homozygosity mapping tool using next-generation sequencing data. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manichaikul, A.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Rich, S.S.; Daly, K.; Sale, M.; Chen, W.M. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2867–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Benyamin, B.; McEvoy, B.P.; Gordon, S.; Henders, A.K.; Nyholt, D.R.; Madden, P.A.; Heath, A.C.; Martin, N.G.; Montgomery, G.W.; et al. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.; Andersson, B.; Arbustini, E.; Bilinska, Z.; Cecchi, F.; Charron, P.; Dubourg, O.; Kuhl, U.; Maisch, B.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: A position statement from the European Society Of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershberger, R.E.; Jordan, E. Dilated Cardiomyopathy Overview. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dhume, A.; Lu, S.; Horowits, R. Targeted disruption of N-RAP gene function by RNA interference: A role for N-RAP in myofibril organization. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2006, 63, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Borst, D.E.; Horowits, R. N-RAP expression during mouse heart development. Dev. Dyn. 2005, 233, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehler, E.; Horowits, R.; Zuppinger, C.; Price, R.L.; Perriard, E.; Leu, M.; Caroni, P.; Sussman, M.; Eppenberger, H.M.; Perriard, J.C. Alterations at the intercalated disk associated with the absence of muscle LIM protein. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 153, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Crawford, G.L.; Dore, J.; Anderson, S.A.; Despres, D.; Horowits, R. Cardiac-specific NRAP overexpression causes right ventricular dysfunction in mice. Exp. Cell Res. 2011, 317, 1226–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Family A | Family B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proband (A.IV.13) | Sister with DCM (A.IV.15) | Brother Without DCM (A.IV.14) | Proband (B.IV.5) | |

| Age at onset | 42 years | Early childhood; transplantation at age 6. | 42 years (AF diagnosis 2 months before cardiology assessment). | 66 years (first admission with dyspnea and chest pain). |

| Primary cardiac diagnosis | Dilated cardiomyopathy with reduced EF. | Severe DCM requiring early heart transplantation. | Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy in the setting of atrial fibrillation. | Progressive LV dysfunction with nonischemic injury pattern and HF. |

| Comorbidities | None; no traditional CV risk factors. | Not reported. | Arterial hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance, GERD. | Hypertension, combined hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes. |

| Rhythm/conduction findings | Sinus rhythm; nonspecific inferolateral repolarization changes. | Not reported. | Atrial fibrillation with ventricular response 150 bpm on ECG. | Sinus rhythm with bigeminal ventricular ectopy, NSVT; later sinus bradycardia, LBBB, frequent ventricular ectopy. |

| Baseline LV size and systolic function | Dilated LV with globally reduced systolic function; EF 45%. | Severe dysfunction necessitating transplant (exact EF not available). | Non-dilated LV with globally reduced systolic function; EF 30%. | Initially preserved LV size and thickness with septal hypokinesia, EF 50%; later LV dilation with moderate dysfunction, EF 48%. |

| Diastolic function | Not specifically reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Diastolic dysfunction on initial echo. |

| Valvular abnormalities | Mild mitral and aortic regurgitation. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Mild annuloaortic ectasia; mild mitral regurgitation; later mild–moderate aortic insufficiency and low-grade aortic regurgitation. |

| Ventricle size and function | Not specifically abnormal. | Not reported. | Not reported as abnormal; focus on LV dysfunction. | Preserved RV size initially; later slight reduction in RV systolic function. |

| Advanced imaging (CMR) | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | CMR: moderate–severe LV systolic impairment with focal nonischemic LGE in septum and junctions. |

| Biomarkers | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Persistent elevation of cTnI and NT-proBNP. |

| Clinical course/severity | Mid-life DCM with moderate LV dysfunction, clinically stable on optimal therapy and ICD. | Malignant early childhood course with transplant at 6 years. | AF-related tachycardia cardiomyopathy with significant LV dysfunction but structurally non-dilated LV. | Adult-onset, progressively worsening HF with recurrent symptoms and arrhythmias, leading to death over 6 years. |

| Outcome | Alive with DCM, ICD in place, good functional status on therapy. | Survived via orthotopic heart transplantation in early childhood. | Alive; managed for AF and tachycardia-induced LV dysfunction (no DCM diagnosis). | Death 6 years after initial clinical presentation. |

| Reference | Age at Onset, Sex | Parents | Phenotype | HGVS Nomenclature | Exon | Domain | Variant Type | Zigosity | Died (Age) | ACMG Classification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [4] | 1 proband | not reported | consanguineous | DCM | c.400_407del, p.(Cys134SerfsTer12) | 5 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | P (PVS1, PP5, PM2) | |

| [5] | 2 related probands | 26 y, M | unrelated | DCM | c.4504C > T, p.(Arg1502Ter) | 38 | NSR | Nonsense | Hom | LP(PP3, PM2, PP5) | |

| 36 y, M | unrelated | asymptomatic | c.4504C > T, p.(Arg1502Ter) | 38 | NSR | Nonsense | Hom | LP(PP3, PM2, PP5) | |||

| [6] | 1 proband | 3 y 5mo, F | unrelated | DCM | c.1344T > A, p.(Tyr448Ter) | 14 | NR | Nonsense | Hom | 3 y 8mo | P (PVS1, PM2, PP5) |

| [3] | 1 proband and Father | 13 mo, F | consanguineous | DCM | c.400_407del, p.(Cys134SerfsTer12) | 5 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | P (PVS1, PP5, PM2) | |

| 33 y, M | not reported | asymptomatic | c.400_407del, p.(Cys134SerfsTer12) | 5 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | P (PVS1, PP5, PM2) | |||

| [12] | 1 Proband | 10 y, M | consanguineous | DCM | c.400_407del, p.(Cys134SerfsTer12) | 5 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | 13 y | P (PVS1, PP5, PM2) |

| 1 Proband | 9 mo, F | consanguineous | DCM | c.400_407del, p.(Cys134SerfsTer12) | 5 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | 9 mo | P (PVS1, PP5, PM2) | |

| 1 Proband | 2 y, M | consanguineous | DCM | c.760del, p.(Arg254GlufsTer9) | 8 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | 7 y | P (PVS1, PM2,PP5) | |

| 1 Proband | 22 mo, F | consanguineous | DCM | c.760del, p.(Arg254GlufsTer9) | 8 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | 4 y | P (PVS1, PM2,PP5) | |

| 1 Proband | 12 y, F | consanguineous | DCM | c.1019del, p.(Lys340ArgfsTer2) | 11 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | 13 y | P (PVS1, PM2,PP5) | |

| 1 Proband | 2 y, M | consanguineous | DCM | c.1579del, p.(Gln527ArgfsTer7) | 16 | NSR | Frameshift | Hom | P (PVS1, PM2,PP5) | ||

| 1 Proband | 4 y, F | consanguineous | DCM | c.3568G > T, p.(Glu1190Ter) | 31 | NSR | Nonsense | Hom | P (PVS1, PM2,PP5) | ||

| [7] | 11 unrelated probands | 19 y, F | not reported | DCM | c.3099G > A, p.(Trp1033Ter) | 28 | NSR | Nonsense | Hom | P (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | |

| 22 y, M | not reported | DCM | c.4371del, p.(Thr1458GlnfsTer36) | 37 | NSR | Frameshift | Hom | LP (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | |||

| 53 y, F | not reported | DCM | c.3109C > T, p.(Arg1037Ter) | 28 | NSR | Nonsense | Hom | P (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | |||

| 2 y, M | not reported | DCM | c.1344T > A, p.(Tyr448Ter) | 14 | NR | Nonsense | Hom | 2 y | P (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | ||

| 36 y, F | not reported | DCM | c.4371del, p.(Thr1458GlnfsTer36) | 37 | NSR | Frameshift | Het Comp | 38 y | LP (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | ||

| c.72G > C, p.(Gln24His) | 1 | LIM | Missense | VUS (PP3, PM2, PP5, BP1) | |||||||

| 28 y, M | not reported | DCM | c.4371del, p.(Thr1458GlnfsTer36) | 37 | NSR | Frameshift | Het Comp | LP (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | |||

| c.72G > C, p.(Gln24His) | 1 | LIM | Missense | VUS (PP3, PM2, PP5, BP1) | |||||||

| 56 y, M | not reported | DCM | c.1344T > A, p.(Tyr448Ter) | 14 | NR | Nonsense | Het Comp | P (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | |||

| c.49G > A, p.(Glu17Lys) | 1 | LIM | Missense | VUS (PP3, PM2, BP1) | |||||||

| 4 y, F | not reported | DCM | c.4371del, p.(Thr1458GlnfsTer36) | 37 | NSR | Frameshift | Het Comp | LP (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | |||

| c.4504C > T, p.(Arg1502Ter) | 38 | NSR | Nonsense | LP(PP3, PM2, PP5) | |||||||

| 46 y, F | not reported | DCM | c.72G > C, p.(Gln24His) | 1 | LIM | Missense | Het Comp | VUS (PP3, PM2, PP5, BP1) | |||

| c.4504C > T, p.(Arg1502Ter) | 38 | NSR | Nonsense | LP(PP3, PM2, PP5) | |||||||

| 59 y, M | not reported | DCM | c.72G > C, p.(Gln24His) | 1 | LIM | Missense | Het Comp | VUS (PP3, PM2, PP5, BP1) | |||

| c.4504C > T, p.(Arg1502Ter) | 38 | NRS | Nonsense | LP(PP3, PM2, PP5) | |||||||

| 48 y, M | not reported | DCM | c.4025G > A, p.(Ser1342Asn) | 35 | NRS | Missense | Het Comp | VUS (PM2, BP1) | |||

| c.2T > C, p.(Met1Thr) | 1 | LIM | Start loss | P (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | |||||||

| [8] | 3 unrelated probands | 3 y, M | not reported | HCM | c.5011G > A, p.(Gly1671Ser) | 41 | NRS | Missense | Hom | VUS (PM2, PP3, BP1) | |

| 4 y, F | consanguineous | DCM | c.400_407del, p.(Cys134SerfsTer12) | 5 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | 5.5 y | P (PVS1, PP5, PM2) | ||

| 19 mo, M | consanguineous | DCM | c.400_407del, p.(Cys134SerfsTer12) | 5 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | P (PVS1, PP5, PM2) | |||

| [9] | 1 proband | 5 y, M | unrelated | LVNC | c.259delC, p.(His87MetfsTer17) | 4 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | P (PVS1, PM2, PP5) | |

| [10] | 1 proband | 66 y, M | unrelated | DCM | c.619del, p.(Val207TrpfsTer20) | 7 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | 72 y | LP (PVS1, PM2) |

| Family A This report | 2 affected sibling | 42 y, M | consanguineous | DCM | c.619del, p.(Val207TrpfsTer20) | 7 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | LP (PVS1, PM2) | |

| 3 y, F | DCM | c.619del, p.(Val207TrpfsTer20) | 7 | NR | Frameshift | Hom | LP (PVS1, PM2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onore, M.E.; Caiazza, M.; Mio, C.; Scarano, G.; Di Letto, P.; Rahman, S.I.; Monda, E.; Amarelli, C.; Borrelli, R.N.; Faletra, F.; et al. Common Ancestry from Southern Italy: Two Families with Dilated Cardiomyopathy Share the Same Homozygous Loss-of-Function Variant in NRAP. Genes 2025, 16, 1470. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121470

Onore ME, Caiazza M, Mio C, Scarano G, Di Letto P, Rahman SI, Monda E, Amarelli C, Borrelli RN, Faletra F, et al. Common Ancestry from Southern Italy: Two Families with Dilated Cardiomyopathy Share the Same Homozygous Loss-of-Function Variant in NRAP. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1470. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121470

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnore, Maria Elena, Martina Caiazza, Catia Mio, Gioacchino Scarano, Pasquale Di Letto, Sarah Iffat Rahman, Emanuele Monda, Cristiano Amarelli, Rossella Nicoletta Borrelli, Flavio Faletra, and et al. 2025. "Common Ancestry from Southern Italy: Two Families with Dilated Cardiomyopathy Share the Same Homozygous Loss-of-Function Variant in NRAP" Genes 16, no. 12: 1470. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121470

APA StyleOnore, M. E., Caiazza, M., Mio, C., Scarano, G., Di Letto, P., Rahman, S. I., Monda, E., Amarelli, C., Borrelli, R. N., Faletra, F., Nigro, V., Limongelli, G., & Piluso, G. (2025). Common Ancestry from Southern Italy: Two Families with Dilated Cardiomyopathy Share the Same Homozygous Loss-of-Function Variant in NRAP. Genes, 16(12), 1470. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121470