Expression and Regulation of FGF9 Gene in Chicken Ovarian Follicles and Its Genetic Effect on Laying Traits in Hens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sample Collections

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.3. RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.4. Construction and Dual-Luciferase Analysis of Chicken FGF9 Promoter Vectors

2.5. Genotyping

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

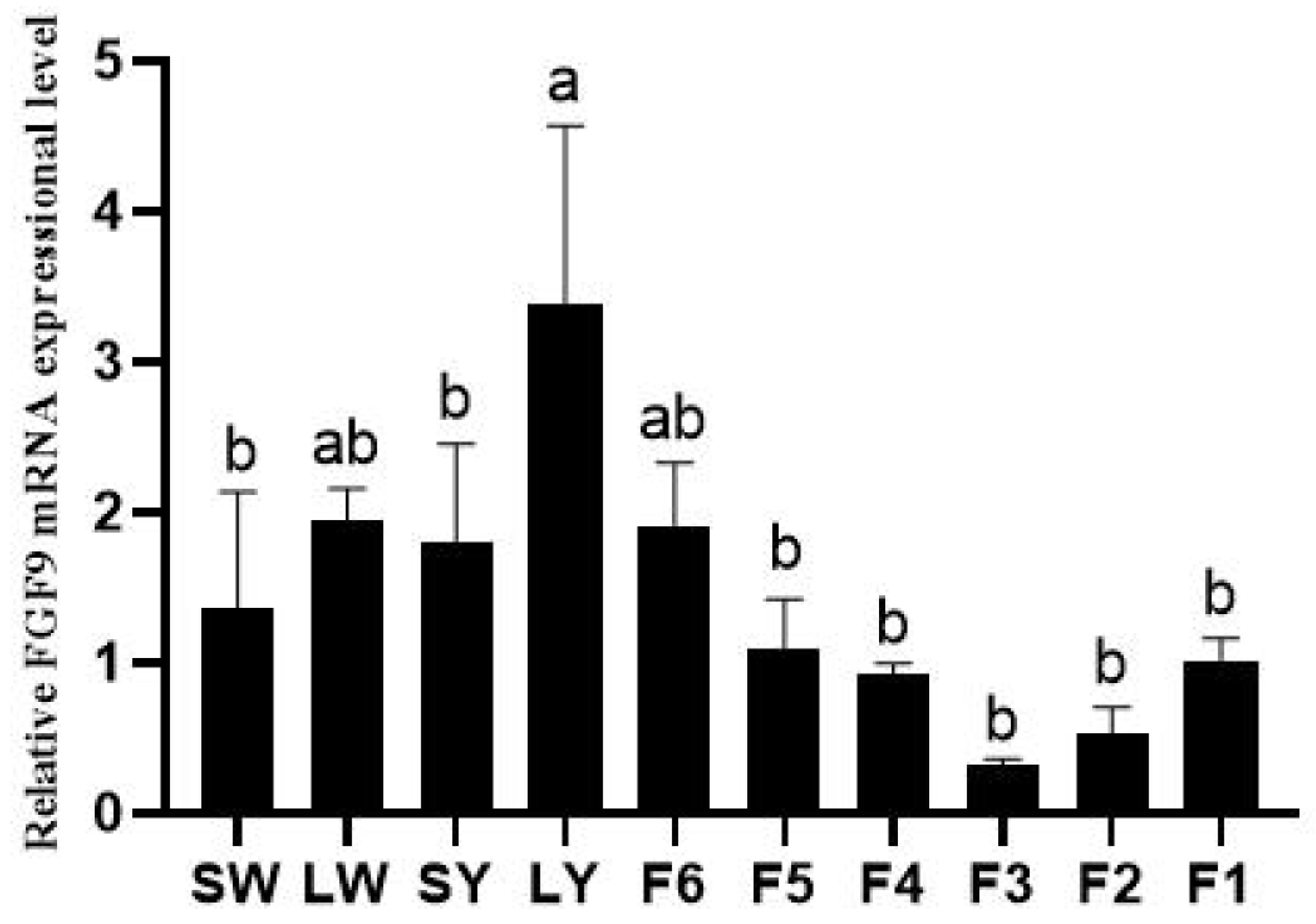

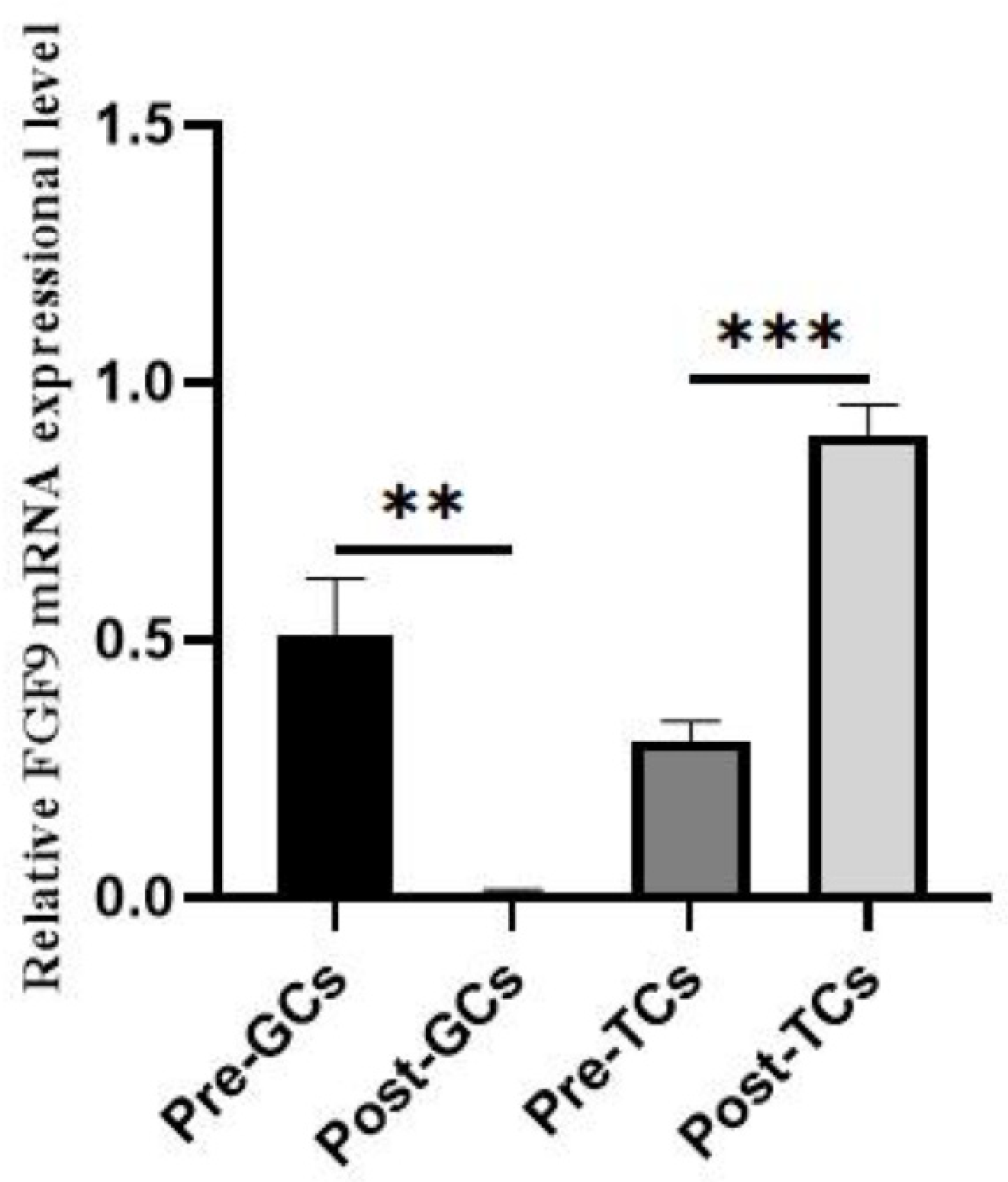

3.1. Expression of Chicken FGF9 mRNA in Different Ovarian Follicles, Follicular Granulosa Cells, and Theca Cells

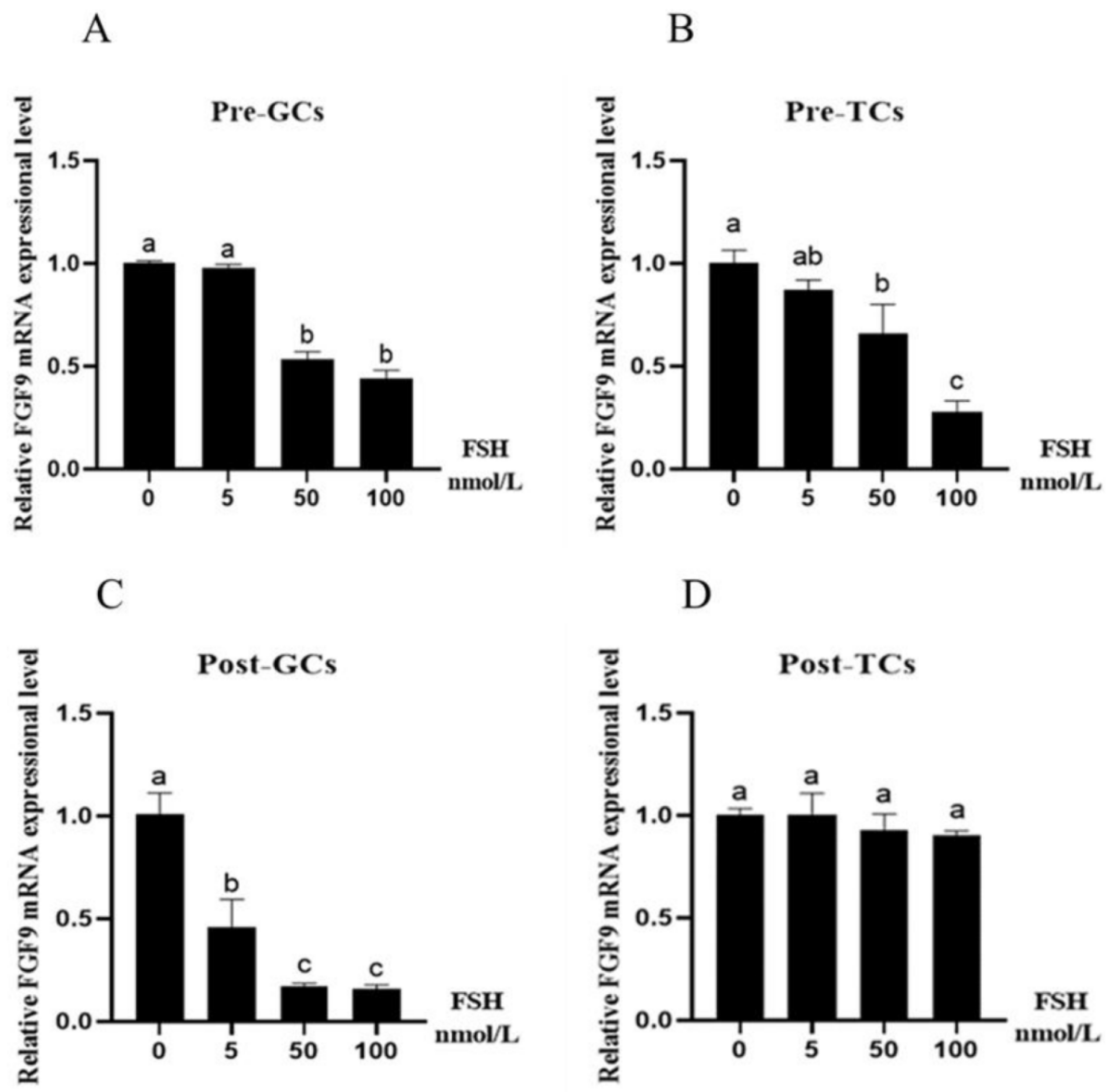

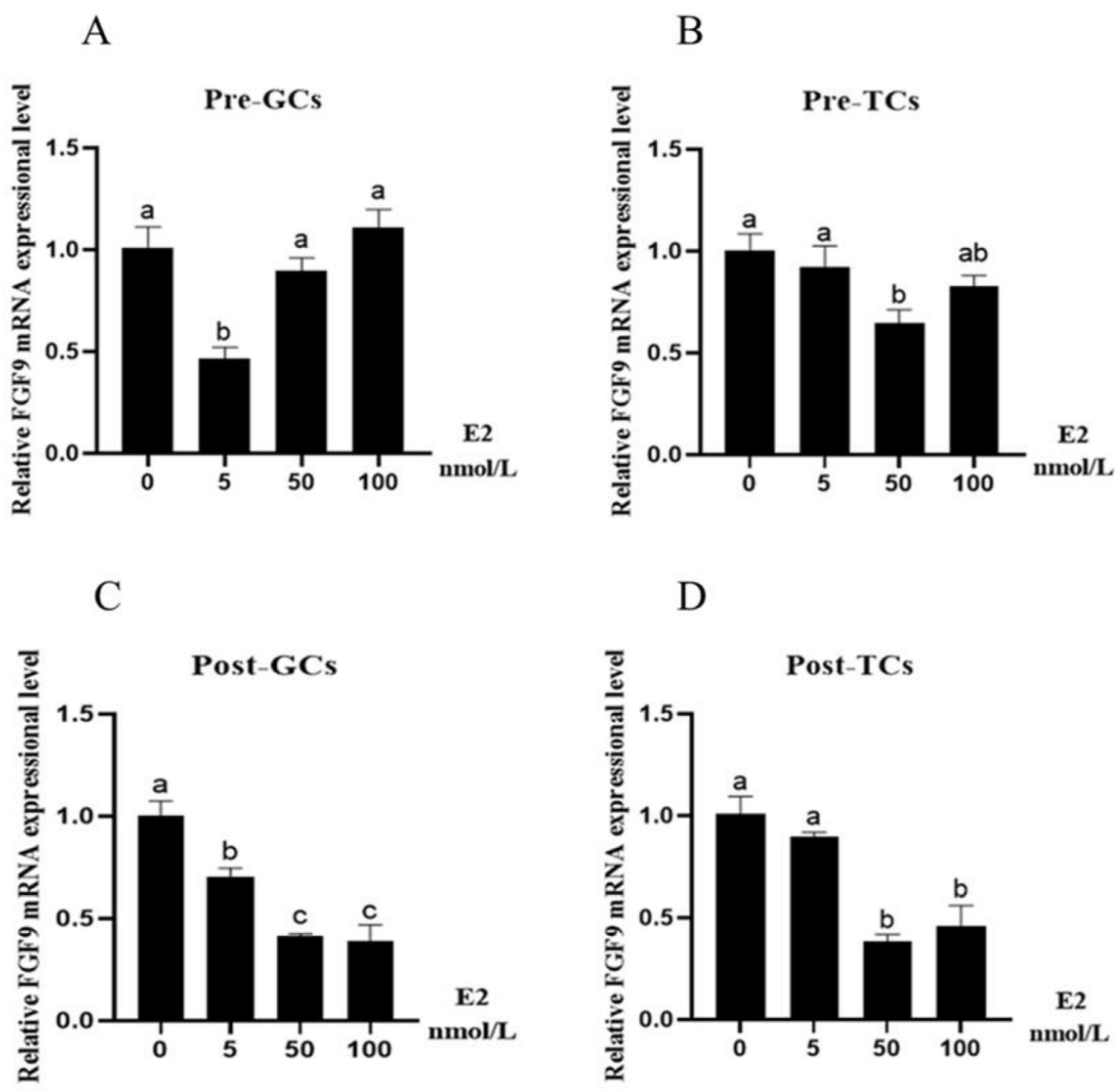

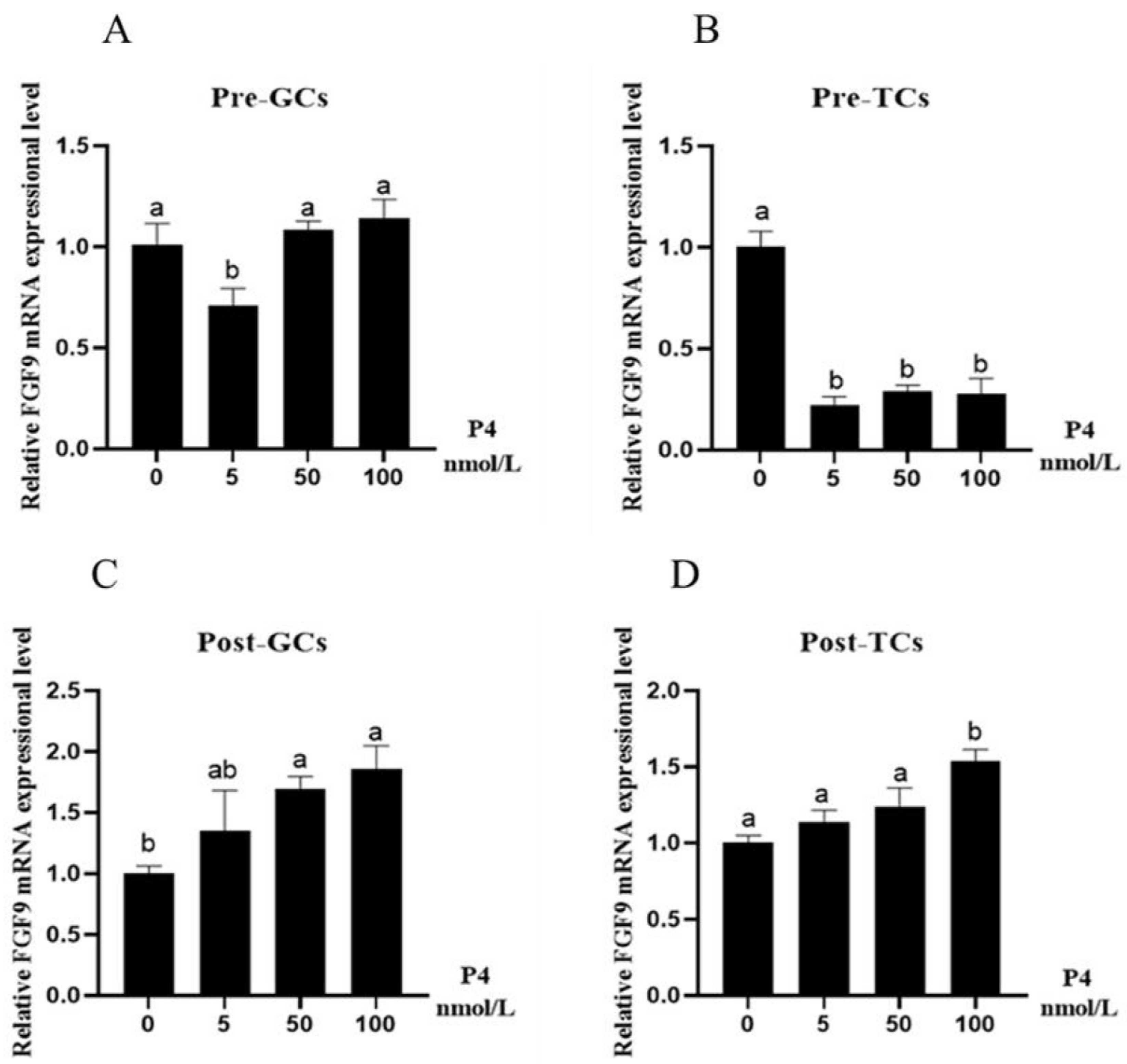

3.2. Effect of Reproductive Hormones on Chicken FGF9 mRNA Expression

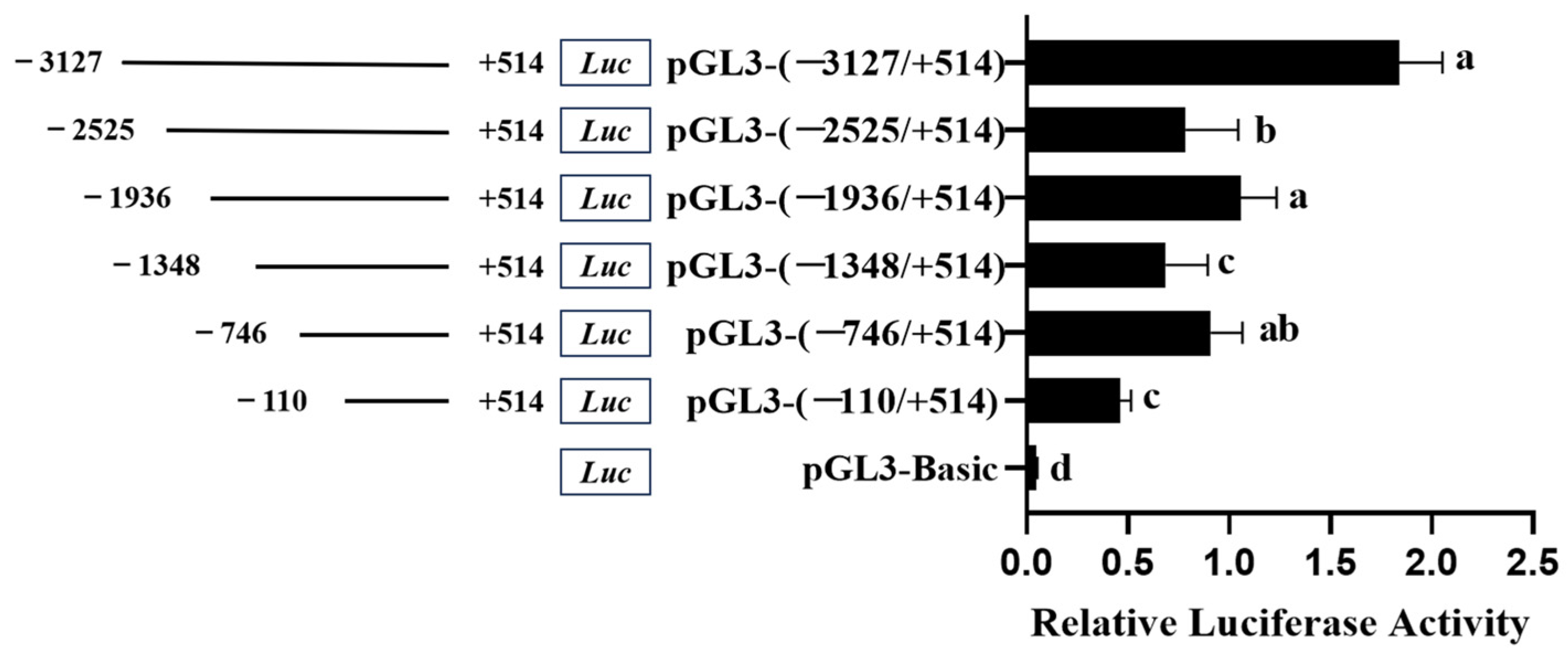

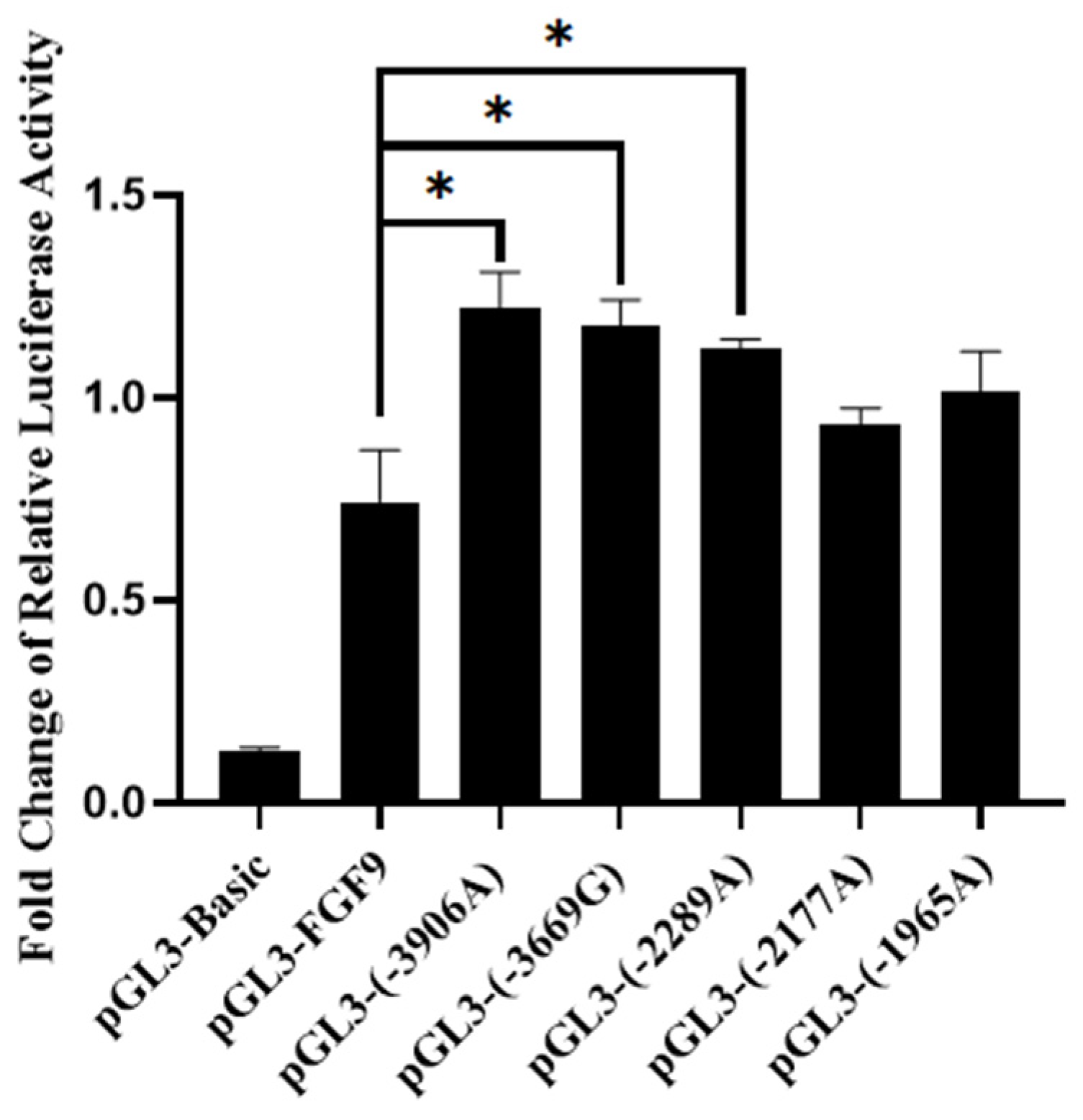

3.3. Promoter Activity of Chicken FGF9 Gene

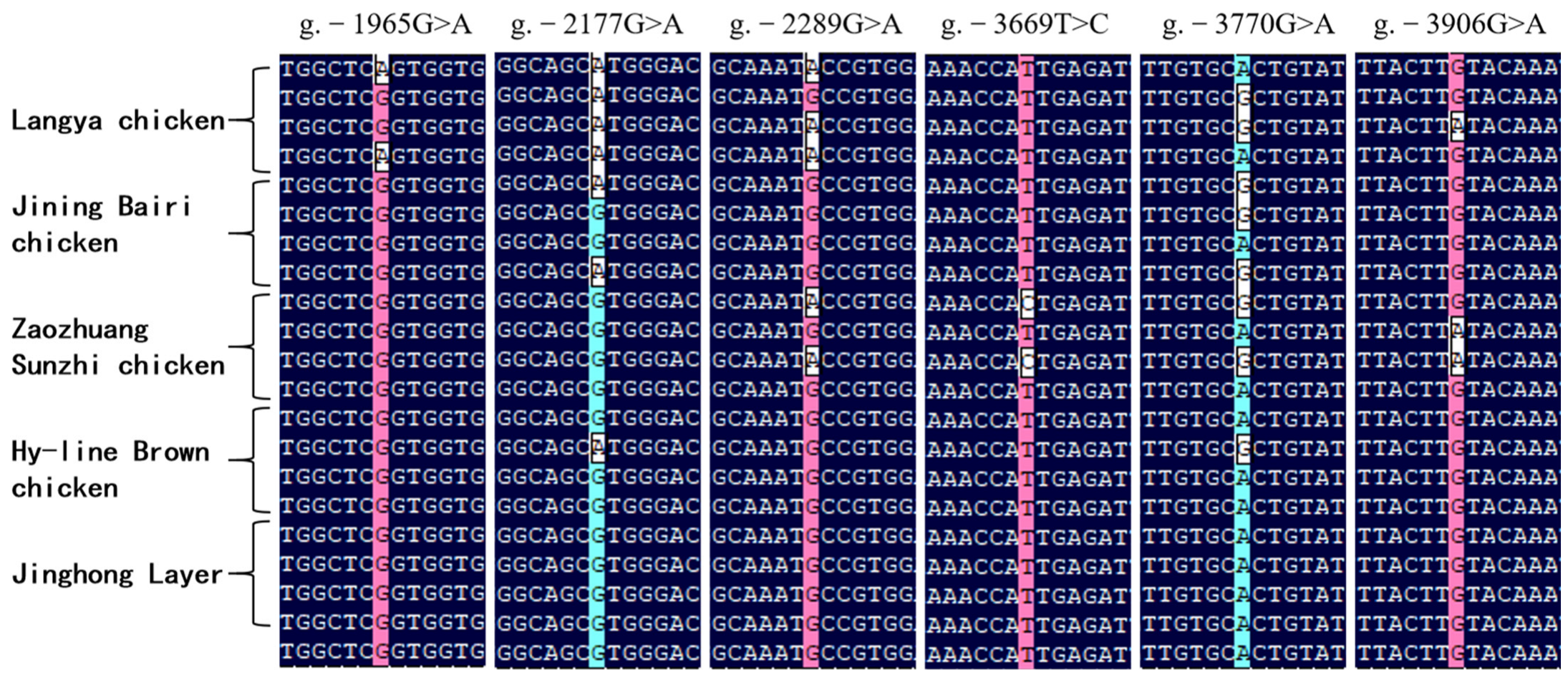

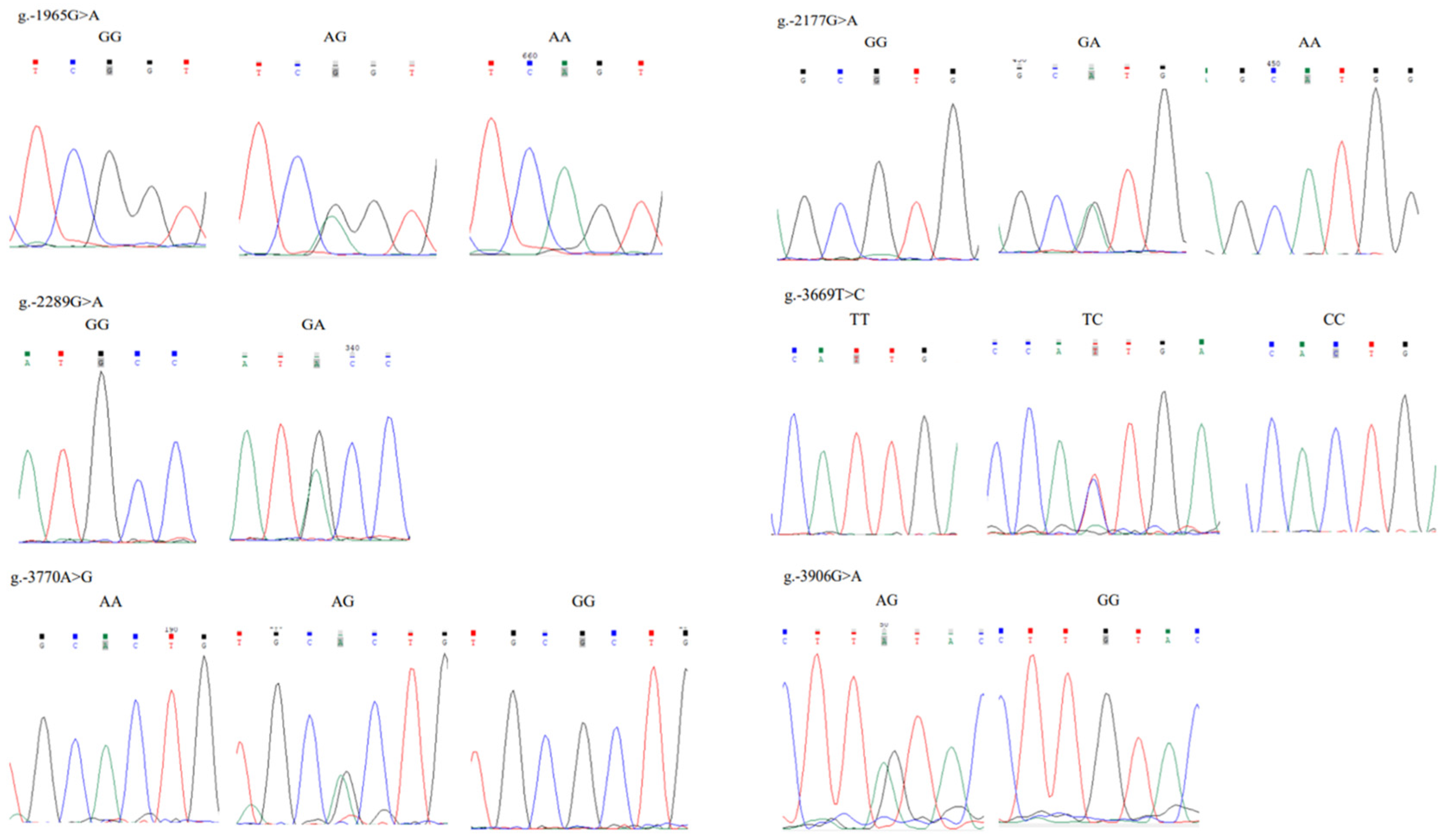

3.4. Polymorphisms in the Critical Promoter Region of Chicken FGF9 Gene

3.5. Association Analysis of SNPs in Chicken FGF9 Promoter Region with Egg-Laying Traits in Jining Bairi Hens

3.6. Effect of SNPs on Transcription Activity of Chicken FGF9

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFE | Age at first egg |

| BW | Body weight at first laying |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| E52 | Number of eggs at 52 weeks |

| EW | Egg weight at first laying |

| FGF9 | Fibroblast growth factor 9 |

| FSH | Follicle Stimulating Hormone |

| IGF | Insulin-like growth factor |

| LCS | Largest clutch size |

| LW | Large white follicles |

| LY | Large yellow follicles |

| P4 | Progesterone |

| Post-GCs | Granulosa cells of hierarchical follicles |

| Post-TCs | Theca cells of hierarchical follicles |

| Pre-GCs | Granulosa cells of pre-hierarchical follicles |

| Pre-TCs | Theca cells of pre-hierarchical follicles |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| SW | Small white follicle |

| SY | Small yellow follicle |

References

- Naruo, K.; Seko, C.; Kuroshima, K.; Matsutani, E.; Sasada, R.; Kondo, T.; Kurokawa, T. Novel secretory heparin-binding factors from human glioma cells (glia-activating factors) involved in glial cell growth. Purification and biological properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 2857–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, M.; Naruo, K.; Seko, C.; Matsumoto, S.; Kondo, T.; Kurokawa, T. Molecular cloning of a novel cytokine cDNA encoding the ninth member of the fibroblast growth factor family, which has a unique secretion property. Mol. Cell Biol. 1993, 13, 4251–4259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chaves, R.N.; de Matos, M.H.; Buratini, J., Jr.; de Figueiredo, J.R. The fibroblast growth factor family: Involvement in the regulation of folliculogenesis. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2012, 24, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laestander, C.; Engström, W. Role of fibroblast growth factors in elicitation of cell responses. Cell Prolif. 2014, 47, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Sekido, R.; DiNapoli, L.; Brennan, J.; Chaboissier, M.C.; Poulat, F.; Behringer, R.R.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Capel, B. Fgf9 and Wnt4 act as antagonistic signals to regulate mammalian sex determination. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.E.; Tellbach, M.; Dyson, M.; Findlay, J.K. Fibroblast growth factor-9, a local regulator of ovarian function. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 3711–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego, M.C.; Morrell, B.C.; Zhang, L.; Schütz, L.F.; Spicer, L.J. Developmental and hormonal regulation of ubiquitin-like with plant homeodomain and really interesting new gene finger domains 1 gene expression in ovarian granulosa and theca cells of cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, skaa205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grado-Ahuir, J.A.; Aad, P.Y.; Spicer, L.J. New insights into the pathogenesis of cystic follicles in cattle: Microarray analysis of gene expression in granulosa cells. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 1769–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totty, M.L.; Morrell, B.C.; Spicer, L.J. Fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9) regulation of cyclin D1 and cyclin-dependent kinase-4 in ovarian granulosa and theca cells of cattle. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2017, 440, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, N.B.; Spicer, L.J. Effects of fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9) on steroidogenesis and gene expression and control of FGF9 mRNA in bovine granulosa cells. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 4491–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R.; Schreiber, N.B.; Williams, J.A.; Spicer, L.J. Effects of fibroblast growth factor 9 on steroidogenesis and control of FGFR2IIIc mRNA in porcine granulosa cells. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grado-Ahuir, J.A.; Aad, P.Y.; Ranzenigo, G.; Caloni, F.; Cremonesi, F.; Spicer, L.J. Microarray analysis of insulin-like growth factor-I-induced changes in messenger ribonucleic acid expression in cultured porcine granulosa cells: Possible role of insulin-like growth factor-I in angiogenesis. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 1921–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Ishimaru, Y.; Sugiyama, N.; Tsunekawa, N.; Noce, T.; Kasahara, M.; Morohashi, K. Mesonephric FGF signaling is associated with the development of sexually indifferent gonadal primordium in chick embryos. Dev. Biol. 2005, 280, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, X.; Guo, C.; Liu, M.; Mi, Y.; Zhang, C. Promotion of the pre-hierarchal follicle growth by postovulatory follicles involving PGE2 -EP2 signaling in chickens. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 8984–8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.A. Follicle selection in the avian ovary. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, E.A.; Hsueh, A.J. Initial and cyclic recruitment of ovarian follicles. Endocr. Rev. 2000, 21, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, Y.; Kang, L.; Jiang, Y. Phosphorylation of LSD1 at serine 54 regulates genes involved in follicle selection by enhancing demethylation activity in chicken ovarian granulosa cells. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.; Gut, I.; Jeffreys, A.J.; Kwok, P.Y.; Brookes, A.J.; Chanock, S.J. Seventh international meeting on single nucleotide polymorphism and complex genome analysis: ‘ever bigger scans and an increasingly variable genome’. Hum. Genet. 2006, 119, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, N.B.; Totty, M.L.; Spicer, L.J. Expression and effect of fibroblast growth factor 9 in bovine theca cells. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 215, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, L.F.; Schreiber, N.B.; Gilliam, J.N.; Cortinovis, C.; Totty, M.L.; Caloni, F.; Evans, J.R.; Spicer, L.J. Changes in fibroblast growth factor 9 mRNA in granulosa and theca cells during ovarian follicular growth in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 9143–9151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.L. Ovarian follicle selection and granulosa cell differentiation. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Johnson, A.L. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietins during hen ovarian follicle development. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2016, 232, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, B.; Leucht, P.; Longaker, M.T.; Quarto, N. Fgf-9 is required for angiogenesis and osteogenesis in long bone repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11853–11858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.J.; Wu, M.H.; Chen, H.M.; Chuang, P.C.; Wing, L.Y. Fibroblast growth factor-9 is an endometrial stromal growth factor. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 2715–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, F.; Huang, J.; Zheng, L.; Luo, T. Progestin and adipoQ receptor 7 (PAQR7) mediate the anti-apoptotic effect of P4 on human granulosa cells and its deficiency reduces ovarian function in female mice. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrabia, A.; Wolak, D.; Kwaśniewska, M.; Kieronska, A.; Socha, J.K.; Sechman, A. Expression of gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP-2 and TIMP-3) in the chicken ovary in relation to follicle development and atresia. Theriogenology 2019, 125, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onagbesan, O.; Bruggeman, V.; Decuypere, E. Intra-ovarian growth factors regulating ovarian function in avian species: A review. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2009, 111, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5′-3′) | Annealing Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| FGF9-F | ACCTGTACCAGTCAAAGCAGAATA | 62.0 |

| FGF9-R | GTGCCAAACCCAGGAGATATAAGA | |

| GAPDH-F | GAGGGTAGTGAAGGCTGCTG | 62.0 |

| GAPDH-R | CACAACACGGTTGCTGTATC | |

| F1-KpnI | CGGGGTACCCAGTTTGCTGACTCAAGGC | 61.0 |

| R-MluI | CGACGCGTTCCGTAGTTTCTCCATTTGG | |

| F2-KpnI | CGGGGTACCTTCCTGCCTCTGTGTCTTG | 58.4 |

| R-MluI | CGACGCGTTCCGTAGTTTCTCCATTTGG | |

| F3-KpnI | CGGGGTACCCACAAGCCTTCACTCCTCA | 58.4 |

| R-MluI | CGACGCGTTCCGTAGTTTCTCCATTTGG | |

| F4-KpnI | CGGGGTACCTGCTTCTGGTGGGATTGT | 58.4 |

| R-MluI | CGACGCGTTCCGTAGTTTCTCCATTTGG | |

| F5-KpnI | CGGGGTACCCCCTTCTGTCCCTTTGCTAA | 58.4 |

| R-MluI | CGACGCGTTCCGTAGTTTCTCCATTTGG | |

| F6-KpnI | CGGGGTACCGCTGGAAGCGGTTCTGTAT | 58.4 |

| R-MluI | CGACGCGTTCCGTAGTTTCTCCATTTGG | |

| Mut-F-1965 | TGAGGCTGCTGGCTCAGTGGTGGGGAAGCCC | 65.0 |

| Mut-R-1965 | GGGCTTCCCCACCACTGAGCCAGCAGCCTCA | |

| Mut-F-2177 | TGCAGGATGGGCAGCATGGGACCCTGCCCTG | 65.0 |

| Mut-R-2177 | CAGGGCAGGGTCCCATGCTGCCCATCCTGCA | |

| Mut-F-2289 | ATATATATGGCAAATACCGTGGAACATGACC | 55.9 |

| Mut-R-2289 | GGTCATGTTCCACGGTATTTGCCATATATAT | |

| Mut-F-3669 | TTCTTATTAATCTCAGTGGTTTTGCAGAGTA | 55.9 |

| Mut-R-3669 | TACTCTGCAAAACCACTGAGATTAATAAGAA | |

| Mut-F-3906 | AGCTCTCATTTACTTATACAAATCTTCCAGT | 55.9 |

| Mut-R-3906 | ACTGGAAGATTTGTATAAGTAAATGAGAGCT | |

| P-FGF9-F1 | CAGTTTGCTGACTCAAGGC | 58.4 |

| P-FGF9-R1 | AGATTCACACCCACTTCCC | |

| P-FGF9-F2 | AACTTCCTTCTGCCGCACA | 58.4 |

| P-FGF9-R2 | CGGTGCCAATGATGATGT |

| Site | Traits | Genotype (Number of Hens) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g.-1965 G>A | GG (290) | GA (20) | AA (13) | ||

| AFE | 150.18 ± 0.48 | 148.70 ± 1.83 | 148.46 ± 2.27 | 0.579 | |

| E52 | 143.80 ± 1.34 | 151.75 ± 5.08 | 144.39 ± 6.31 | 0.320 | |

| LCS | 20.60 ± 0.96 | 26.10 ± 3.66 | 16.15 ± 4.54 | 0.205 | |

| BW | 1473.32 ± 9.89 | 1444.00 ± 37.67 | 1339.15 ± 46.73 | 0.017 * | |

| EW | 33.16 ± 0.24 | 32.10 ± 0.91 | 31.49 ± 1.13 | 0.204 | |

| g.-2177 G>A | GG (296) | GA (31) | AA (12) | ||

| AFE | 149.78 ± 0.48 | 148.74 ± 1.47 | 147.17 ± 2.37 | 0.465 | |

| E52 | 143.85 ± 1.33 | 150.39 ± 4.12 | 136.83 ± 6.62 | 0.170 | |

| LCS | 20.51 ± 0.95 | 28.90 ± 2.94 | 13.33 ± 4.72 | 0.007 * | |

| BW | 1470.97 ± 9.47 | 1428.55 ± 29.26 | 1415.00 ± 47.03 | 0.216 | |

| EW | 33.03 ± 0.23 | 33.37 ± 0.72 | 34.72 ± 1.16 | 0.342 | |

| g.-2289 G>A | GG (327) | GA (9) | AA (12) | ||

| AFE | 149.89 ± 0.44 | 143.11 ± 2.67 | 150.42 ± 2.32 | 0.043 * | |

| E52 | 144.52 ± 1.26 | 149.44 ± 7.60 | 141.00 ± 6.59 | 0.703 | |

| LCS | 20.91 ± 0.90 | 22.33 ± 5.43 | 18.75 ± 4.70 | 0.870 | |

| BW | 1466.54 ± 9.37 | 1477.78 ± 56.49 | 1482.08 ± 48.92 | 0.936 | |

| EW | 32.96 ± 0.22 | 34.31 ± 1.30 | 33.51 ± 1.13 | 0.534 | |

| g.-3669 A>G | AA (299) | AG (31) | GG (11) | ||

| AFE | 149.96 ± 0.48 | 147.84 ± 1.48 | 152.46 ± 2.49 | 0.226 | |

| E52 | 144.36 ± 1.32 | 153.97 ± 4.11 | 137.27 ± 6.89 | 0.045 * | |

| LCS | 21.00 ± 0.94 | 21.71 ± 2.93 | 20.91 ± 4.91 | 0.973 | |

| BW | 1466.83 ± 9.70 | 1470.00 ± 30.12 | 1456.36 ± 50.56 | 0.973 | |

| EW | 33.11 ± 0.24 | 33.02 ± 0.73 | 32.75 ± 1.23 | 0.954 | |

| g.-3770 A>G | AA (242) | AG (42) | GG (42) | ||

| AFE | 149.87 ± 0.54 | 149.07 ± 1.29 | 150.67 ± 1.29 | 0.683 | |

| E52 | 145.24 ± 1.49 | 141.91 ± 3.58 | 140.98 ± 3.58 | 0.427 | |

| LCS | 22.07 ± 1.06 | 17.02 ± 2.54 | 20.55 ± 2.54 | 0.180 | |

| BW | 1475.68 ± 10.78 | 1436.98 ± 25.88 | 1459.55 ± 25.88 | 0.361 | |

| EW | 32.88 ± 0.25 | 33.35 ± 0.60 | 33.03 ± 0.60 | 0.756 | |

| g.-3906 G>A | GG (323) | GA (22) | AA (12) | ||

| AFE | 150.03 ± 0.45 | 147.46 ± 1.73 | 149.92 ± 2.34 | 0.354 | |

| E52 | 144.10 ± 1.26 | 157.96 ± 4.82 | 140.92 ± 6.53 | 0.018 * | |

| LCS | 20.77 ± 0.91 | 27.00 ± 3.50 | 18.67 ± 4.74 | 0.200 | |

| BW | 1465.44 ± 9.26 | 1515.23 ± 35.50 | 1451.67 ± 48.07 | 0.376 | |

| EW | 32.96 ± 0.22 | 33.78 ± 0.84 | 32.15 ± 1.14 | 0.486 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Shu, X.; Guo, Y.; Wei, Q.; Jiang, Y. Expression and Regulation of FGF9 Gene in Chicken Ovarian Follicles and Its Genetic Effect on Laying Traits in Hens. Genes 2025, 16, 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121452

Wang Y, Shu X, Guo Y, Wei Q, Jiang Y. Expression and Regulation of FGF9 Gene in Chicken Ovarian Follicles and Its Genetic Effect on Laying Traits in Hens. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121452

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yue, Xinmei Shu, Yuanyuan Guo, Qingqing Wei, and Yunliang Jiang. 2025. "Expression and Regulation of FGF9 Gene in Chicken Ovarian Follicles and Its Genetic Effect on Laying Traits in Hens" Genes 16, no. 12: 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121452

APA StyleWang, Y., Shu, X., Guo, Y., Wei, Q., & Jiang, Y. (2025). Expression and Regulation of FGF9 Gene in Chicken Ovarian Follicles and Its Genetic Effect on Laying Traits in Hens. Genes, 16(12), 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121452