Genomic Characterization of Predominant Delta Variant (B.1.617.2 and AY.120 Sub-Lineages) SARS-CoV-2 Detected from AFI Patients in Ethiopia During 2021–2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

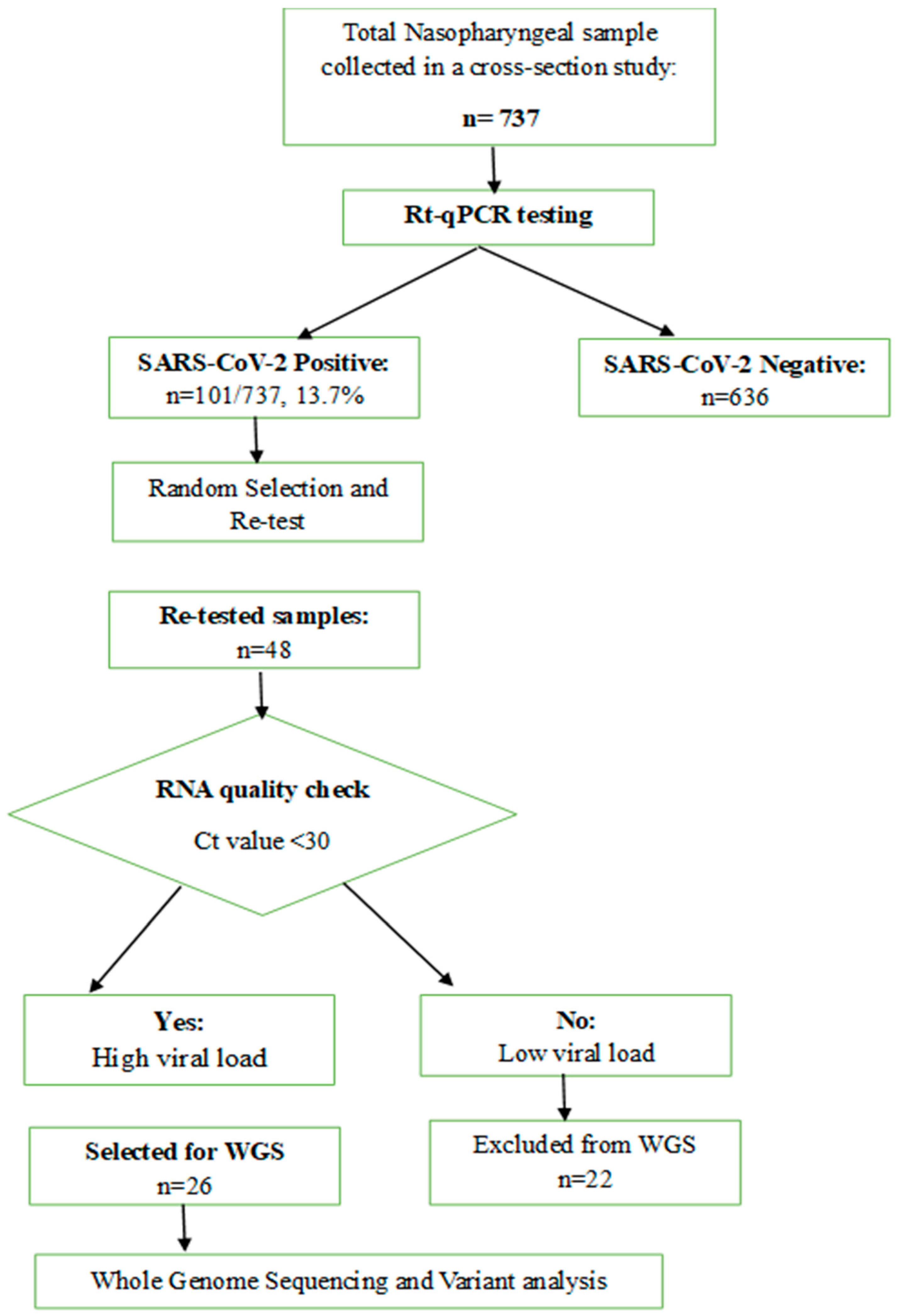

2. Methods and Material

2.1. Ethical Clearance

2.2. Study Population and Specimen Collection

2.3. Viral Load Determination and cDNA Synthesis

2.4. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.5. Variant Calling and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Assembly and Sequencing Metrics of SARS-CoV-2 Raw Read Sequences

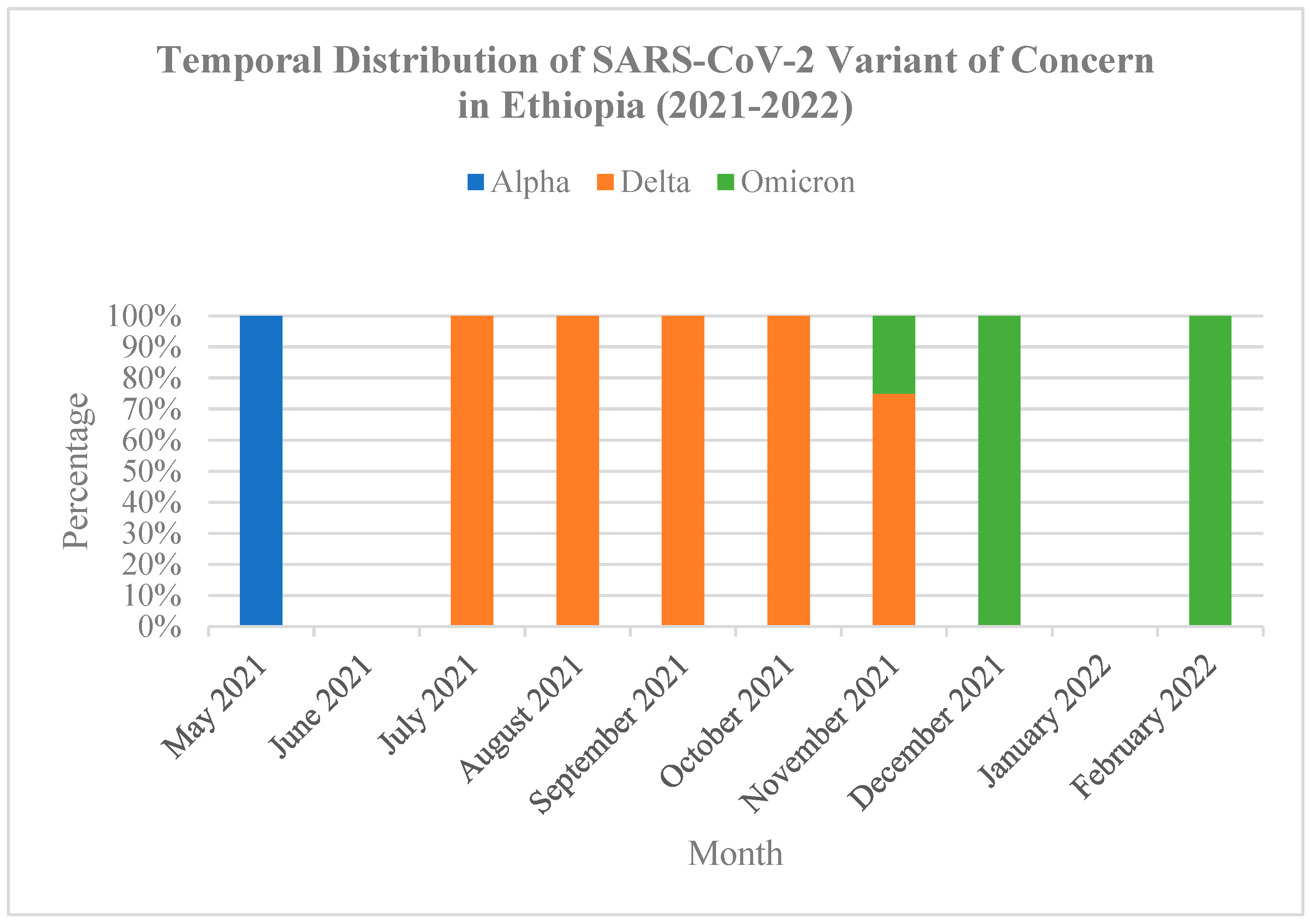

3.3. SARS-CoV-2 Genetic Diversity over the Study Period

3.4. Patterns of SARS-CoV-2 Genetic Variation During the Study

3.5. Nucleotide and Amino Acid Mutation Analysis in SARS-CoV-2 Genes

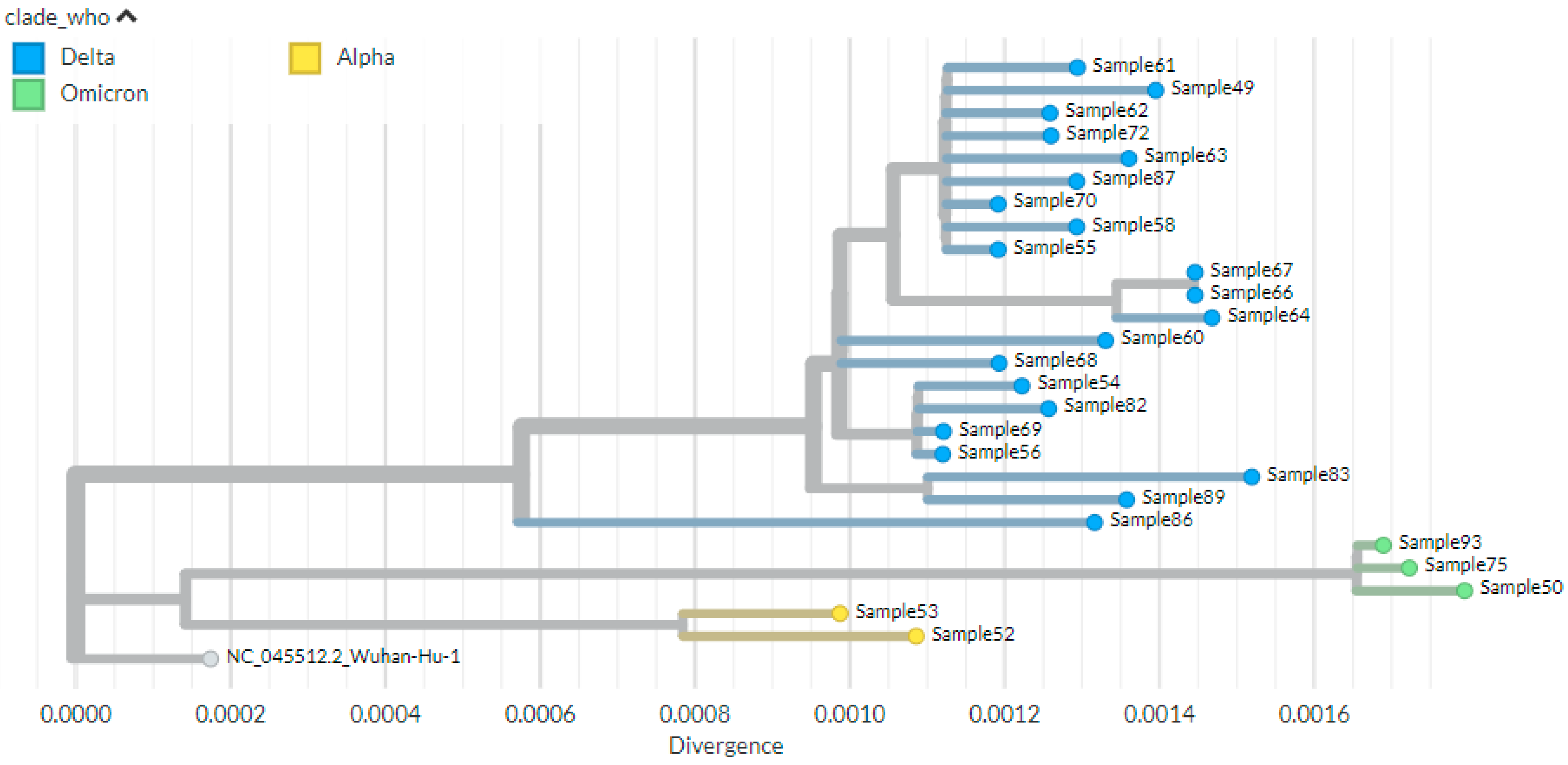

3.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Author Disclaimer

References

- World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Domingo, E.; García-Crespo, C.; Lobo-Vega, R.; Perales, C. Mutation rates, mutation frequencies, and proofreading-repair activities in rna virus genetics. Viruses 2021, 13, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Peng, Y.; Huang, B.; Ding, X.; Wang, X.; Niu, P.; Meng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Genome Composition and Divergence of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Originating in China. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions 2021. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/105817/cdc_105817_DS1.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- (GISAID) GIo, S.A.ID. Tracking of Variants 2021. Available online: https://gisaid.org/hcov19-variants/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- CDC. Delta Variant: What We Know About the Science; US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- Tao, K.; Tzou, P.L.; Nouhin, J.; Gupta, R.K.; de Oliveira, T.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Fera, D.; Shafer, R.W. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Rev. Genet. Nat. Res. 2021, 22, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Guidance on Tools for Detection and Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 Variants Interim Guidance; Version 1.0; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Changes to List of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern, Variants of Interest, and Variants Under Monitoring; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Solna Municipality, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Variants%20page%20changelog_11.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Bhattacharya, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Sharma, A.R.; Lee, S.S.; Chakraborty, C. Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2: Current understanding of infection, transmission, immune escape, and mutational landscape. Folia Microbiol. 2023, 68, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, D.; Veyer, D.; Baidaliuk, A.; Staropoli, I.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Rajah, M.M.; Planchais, C.; Porrot, F.; Robillard, N.; Puech, J.; et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature 2021, 596, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBroome, J.; Thornlow, B.; Hinrichs, A.S.; Kramer, A.; De Maio, N.; Goldman, N.; Haussler, D.; Corbett-Detig, R.; Turakhia, Y. A Daily-Updated Database and Tools for Comprehensive SARSCoV-2 Mutation-Annotated Trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5819–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases Concern. Updates on COVID-19 Variants of 2021. Available online: https://nccid.ca/covid-19-variants (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Mlcochova, P.; Kemp, S.A.; Dhar, M.S.; Papa, G.; Meng, B.; Ferreira, I.A.T.M.; Datir, R.; Collier, D.A.; Albecka, A.; Singh, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 Delta variant replication and immune evasion. Nature 2021, 599, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, W.T.; Carabelli, A.; Ben, J.; Gupta, R.; Thomson, E.C.; Harrison, E.M.; Ludden, C.; Reeve, R.; Rambaut, A.; Peacock, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aga, A.M.; Mulugeta, D.; Gebreegziabxier, A.; Zeleke, G.T.; Girmay, A.M.; Tura, G.B.; Ayele, A.; Mohammed, A.; Belete, T.; Taddele, T.; et al. Genome diversity of SARS-CoV-2 lineages associated with vaccination breakthrough infections in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemayehu, D.H.; Adnew, B.; Alemu, F.; Tefera, D.A.; Seyoum, T.; Beyene, G.T.; Gelanew, T.; Negash, A.A.; Abebe, M.; Mihret, A. Whole-Genome Sequences of SARS-CoV-2 Isolates from Ethiopian Patients. ASM J. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2021, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chekol, M.T.; Sugerman, D.; Tayachew, A.; Mekuria, Z.; Tesfaye, N.; Alemu, A.; Gashu, A.; Shura, W.; Gonta, M.; Agune, A. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 virus among patients with acute febrile illness in selected sites of Ethiopia 2021–2022. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1549159. [Google Scholar]

- Kia, P.; Katagirya, E.; Kakembo, F.E.; Adera, D.A.; Nsubuga, M.L.; Yiga, F.; Aloyo, S.M.; Aujat, B.R.; Anguyo, D.F.; Katabazi, F.A.; et al. Genomic characterization of SARS-CoV-2 from Uganda using MinION nanopore sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.S.; Lam, Y.M.; Law, J.H.Y.; Chan, T.L.; Ma, E.S.K.; Tang, B.S.F. Geographical prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 variants, August 2020 to July 2021. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicot, F.; Trémeaux, P.; Latour, J.; Jeanne, N.; Ranger, N.; Raymond, S.; Dimeglio, C.; Salin, G.; Donnadieu, C.; Izopet, J. Whole-genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: Comparison of target capture and amplicon single molecule real-time sequencing protocols. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.; Kleynhans, J.; von Gottberg, A.; McMorrow, M.L.; Wolter, N.; Bhiman, J.N.; Moyes, J.; du Plessis, M.; Carrim, M.; Buys, A.; et al. Characteristics of infections with ancestral, Beta and Delta variants of SARS-CoV-2 in the PHIRST-C community cohort study, South Africa, 2020–2021. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegally, H.; San, J.E.; Cotten, M.; Moir, M.; Tegomoh, B.; Mboowa, G.; Martin, D.P.; Baxter, C.; Lambisia, A.W.; Diallo, A.; et al. The evolving SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Africa: Insights from rapidly expanding genomic surveillance. Science 2022, 378, 6615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Science Brief: COVID-19 Vaccines and Vaccination; US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- Smallman-Raynor, M.R.; Cliff, A.D.; COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium. Spatial growth rate of emerging SARS-CoV-2 lineages in England, September 2020–December 2021. Epidemiol. Infect. 2022, 150, e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangavarapu, K.; Latif, A.A.; Mullen, J.L.; Alkuzweny, M.; Hufbauer, E.; Tsueng, G.; Haag, E.; Zeller, M.; Aceves, C.M.; Zaiets, K.; et al. Outbreak.info genomic reports: Scalable and dynamic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 variants and mutations. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taboada, B.; Zárate, S.; García-López, R.; Muñoz-Medina, J.E.; Sanchez-Flores, A.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Boukadida, C.; Gómez-Gil, B.; Mojica, N.S.; Rosales-Rivera, M.; et al. Dominance of Three Sublineages of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant in Mexico. Viruses 2022, 14, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranasinghe, D.; Jayathilaka, D.; Jeewandara, C.; Gunasinghe, D.; Ariyaratne, D.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Kuruppu, H.; Wijesinghe, A.; Bary, F.F.; Madhusanka, D.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of AY.28 and AY.104 Delta Sub-lineages in Sri Lanka. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 873633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulimilli, S.V.; Dallavalasa, S.; Basavaraju, C.G.; Kumar Rao, V.; Chikkahonnaiah, P.; Madhunapantula, S.V.; Veeranna, R.P. Variants of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Vaccine Effectiveness. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamlan, F.S.; Al-Qahtani, A.A. SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Genetic Insights, Epidemiological Tracking, and Implications for Vaccine Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Yin, H.; Yin, J.Y. B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant of SARS-CoV-2: Features, transmission and potential strategies. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 1844–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shayan, S.; Jamaran, S.; Askandar, R.H.; Rahimi, A.; Elahi, A.; Farshadfar, C.; Ardalan, N. The SARS-CoV-2 Proliferation Blocked by a Novel and Potent Main Protease Inhibitor via Computer-aided Drug Design. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 20, 399–418. [Google Scholar]

- Hoteit, R.; Yassine, H.M. Biological Properties of SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Epidemiological Impact and Clinical Consequences. Vaccines 2022, 10, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabelli, A.M.; Peacock, T.P.; Thorne, L.G.; Harvey, W.T.; Hughes, J.; COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium; Peacock, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; de Silva, T.I.; Towers, G.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: Immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 162–177. [Google Scholar]

- Katowa, B.; Kalonda, A.; Mubemba, B.; Matoba, J.; Shempela, D.M.; Sikalima, J.; Kabungo, B.; Changula, K.; Chitanga, S.; Kasonde, M.; et al. Genomic Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in the Southern Province of Zambia: Detection and Characterization of Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Omicron Variants of Concern. Viruses 2022, 14, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G/Meskel, W.; Desta, K.; Diriba, R.; Belachew, M.; Evans, M.; Cantarelli, V.; Urrego, M.; Sisay, A.; Gebreegziabxier, A.; Abera, A. SARS-CoV-2 variant typing using real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction–based assays in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. IJID Reg. 2024, 11, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sow, M.S.; Togo, J.; Simons, L.M.; Diallo, S.T.; Magassouba, M.L.; Keita, M.B.; Somboro, A.M.; Coulibaly, Y.; Ozer, E.A.; Hultquist, J.F.; et al. Genomic characterization of SARS-CoV-2 in Guinea, West Africa. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibu, J.O.; Onwuamah, C.K.; James, A.B.; Okwuraiwe, A.P.; Amoo, O.S.; Salu, O.B.; Ige, F.A.; Liboro, G.; Odewale, E.; Okoli, L.C.; et al. Full-length genomic sanger sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0243271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, S.; Gou, J.; Guo, Y.; Kong, X. Genetic Surveillance of Five SARS-CoV-2 Clinical Samples in Henan Province Using Nanopore Sequencing. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 814806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Frequency (n = 48) | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 22 | 46% |

| Male | 26 | 54% | |

| Age | 15–24 Years old | 3 | 6% |

| 25–44 Years old | 22 | 46% | |

| 45–64 years old | 8 | 17% | |

| 65+ | 15 | 31% | |

| Symptoms | Fever | 48 | 100% |

| Cough | 40 | 83% | |

| Sore Throat | 31 | 65% | |

| Difficulty of breathing | 27 | 56% | |

| Headache | 34 | 71% | |

| Muscle ache | 30 | 63% | |

| Arthralgia | 16 | 33% | |

| Admission Status | Inpatient | 43 | 90% |

| Outpatient | 5 | 10% | |

| Barcode | # Reads | Depth of Coverage | Nucleotide Identity (%) | Amino Acid Identity (%) | Genome Coverage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49 | 27,604 | 485 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 50 | 27,620 | 502 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 96.0 |

| 52 | 55,585 | 1014 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.4 |

| 53 | 15,574 | 279 | 99.9 | 99.8 | 99.4 |

| 54 | 28,642 | 486 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 55 | 42,675 | 769 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 56 | 51,054 | 915 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 58 | 27,377 | 485 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 60 | 51,101 | 931 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 97.7 |

| 61 | 43,354 | 771 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 62 | 27,608 | 495 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 63 | 55,379 | 979 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 64 | 53,559 | 959 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 66 | 26,429 | 466 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.2 |

| 67 | 53,016 | 937 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 68 | 37,235 | 666 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 98.2 |

| 69 | 26,743 | 467 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 97.5 |

| 70 | 33,827 | 595 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 72 | 35,043 | 610 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.2 |

| 75 | 37,569 | 646 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 99.4 |

| 82 | 46,077 | 841 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 83 | 17,440 | 293 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 95.7 |

| 86 | 23,716 | 430 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 87 | 37,558 | 662 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 89 | 21,772 | 360 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 93 | 54,886 | 949 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| WHO Variant N (%) | Pangolin Lineage N (%) | Next Strain Clade N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | 2 (7.7) | B.1.1.7 | 2 (7.7) | 20I | 2 (7.7) |

| Delta | 21 (80.8) | AY.120 | 12 (46.2) | 21J | 21 (80.8) |

| B.1.617.2 | 7 (26.9) | ||||

| AY.32 | 2 (7.7) | ||||

| Omicron | 3 (11.5) | BA.1.1 | 1 (3.8) | 21K | 3 (11.5) |

| BA.1.17 | 1 (3.8) | ||||

| BA.1 | 1 (3.8) | ||||

| Variant (Sub-Lineage) | Protein | High-Frequency Substitutions (>75%) | High-Frequency Deletions (>75%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha (B.1.1.7) | ORF1a | T1001I, A1708D, P2287S | S3675-, G3676-, F3677- |

| ORF1b | P314L, G662S | ||

| ORF8 | Q27, R52I, K68, Y73C | ||

| N | D3L, R203K, G204R, S235F | ||

| S | N501Y, D614G, P681H | H69-, V70-, Y144- | |

| Delta (B.1.617.2) | ORF1a | A1306S, P2046L, P2287S, V2930L, T3255I, T3646A | |

| ORF1b | P314L, G662S, P1000L, A1918V | ||

| ORF3a | S26L | ||

| ORF7a | V82A, T120I | ||

| ORF7b | T40I | ||

| ORF9b | T60A | ||

| M | I82T | ||

| N | D63G, R203M, G215C, D377Y | ||

| S | T19R, G142D, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N | E156-, F157- | |

| Delta (AY.32) | ORF1a | A1306S, P2046L, P2287S, V2930L, T3255I, T3646A | |

| ORF1b | P314L, G662S, P1000L, A1918V, T2376I, R2613C | ||

| ORF3a | S26L | ||

| ORF7a | V82A, T120I | ||

| ORF7b | T40I | ||

| ORF9b | T60A | ||

| M | I82T | ||

| N | D63G, R203M, G215C, D377Y | ||

| S | T19R, G142D, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N | E156-, F157- | |

| Delta (AY.120) | ORF1a | V28I, A1306S, P2046L, S2048F, P2287S, V2930L, T3255I, T3646A | |

| ORF1b | P314L, G662S, P1000L, A1918V, A2306T | ||

| ORF3a | S26L | ||

| ORF7a | V82A, T120I | ||

| ORF7b | T40I | ||

| ORF9b | T60A | ||

| M | I82T | ||

| N | D63G, R203M, G215C, D377Y | ||

| S | T19R, T95I, G142D, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N | E156-, F157- | |

| Omicron (BA.1; BA.1.1, BA.1.17) | ORF1a | K856R, A2710T, T3255I, P3395H, I3758V | L3674-, S3675-, G3676- |

| ORF1b | P314L, I1566V | ||

| ORF9b | P10S | E27-, N28-, A29- | |

| M | D3G, Q19E, A63T | ||

| N | P13L, R203K, G204R | E31-, R32-, S33- | |

| S | A67V, T95I, G142D, Y145D, L212I, G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, K417N, N440K, G446S, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, T547K, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, L981F | H69-, V70-, G142-, V143-, Y144-, N211- |

| WHO Variant (Clade) | Pango Lineage (Sub-Lineage) | Frequency n (%) [N = 26] | Characteristic High-Frequency Spike Protein Mutations (>75%) | Characteristic Deletions (>75%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha (20I) | B.1.1.7 | 2 (7.7%) | N501Y, D614G, P681H | H69-, V70-, Y144- |

| Delta (21J) | AY.120 | 12 (46.2%) | T19R, G142D, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N | E156-, F157- |

| B.1.617.2 | 7 (26.9%) | T19R, G142D, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N | E156-, F157- | |

| AY.32 | 2 (7.7%) | T19R, G142D, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N | E156-, F157- | |

| Omicron (21K) | BA.1.1, BA.1.17, BA.1 | 3 (11.5%), One (3.8%) for each sub linage | A67V, T95I, G142D, Y145D, G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, K417N, N440K, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, L981F | E27-, N28-, A29-, H69-, V70-, G142-, V143-, Y144-, N211- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chekol, M.T.; Teklu, D.S.; Tayachew, A.; Shura, W.; Agune, A.; Hailemariam, A.; Alemu, A.; Wossen, M.; Hassen, A.; Gonta, M.; et al. Genomic Characterization of Predominant Delta Variant (B.1.617.2 and AY.120 Sub-Lineages) SARS-CoV-2 Detected from AFI Patients in Ethiopia During 2021–2022. Genes 2025, 16, 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111366

Chekol MT, Teklu DS, Tayachew A, Shura W, Agune A, Hailemariam A, Alemu A, Wossen M, Hassen A, Gonta M, et al. Genomic Characterization of Predominant Delta Variant (B.1.617.2 and AY.120 Sub-Lineages) SARS-CoV-2 Detected from AFI Patients in Ethiopia During 2021–2022. Genes. 2025; 16(11):1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111366

Chicago/Turabian StyleChekol, Musse Tadesse, Dejenie Shiferaw Teklu, Adamu Tayachew, Wolde Shura, Admikew Agune, Aster Hailemariam, Aynalem Alemu, Mesfin Wossen, Abdulhafiz Hassen, Melaku Gonta, and et al. 2025. "Genomic Characterization of Predominant Delta Variant (B.1.617.2 and AY.120 Sub-Lineages) SARS-CoV-2 Detected from AFI Patients in Ethiopia During 2021–2022" Genes 16, no. 11: 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111366

APA StyleChekol, M. T., Teklu, D. S., Tayachew, A., Shura, W., Agune, A., Hailemariam, A., Alemu, A., Wossen, M., Hassen, A., Gonta, M., Tesfay, N., Kasa, T., & Kebede, N. (2025). Genomic Characterization of Predominant Delta Variant (B.1.617.2 and AY.120 Sub-Lineages) SARS-CoV-2 Detected from AFI Patients in Ethiopia During 2021–2022. Genes, 16(11), 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111366