Prenatal Diagnosis of 6q Terminal Deletion Associated with Coffin–Siris Syndrome: Phenotypic Delineation and Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

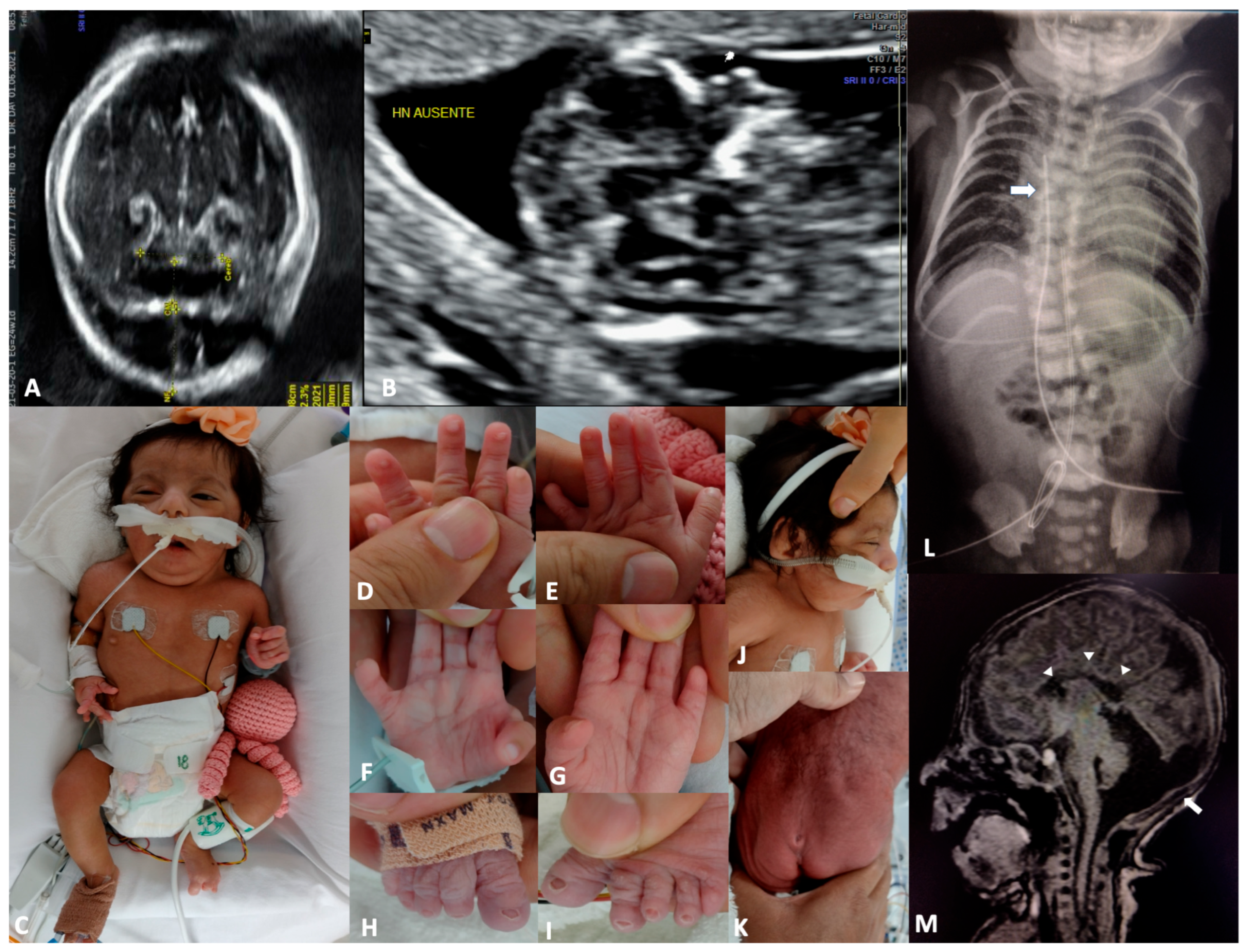

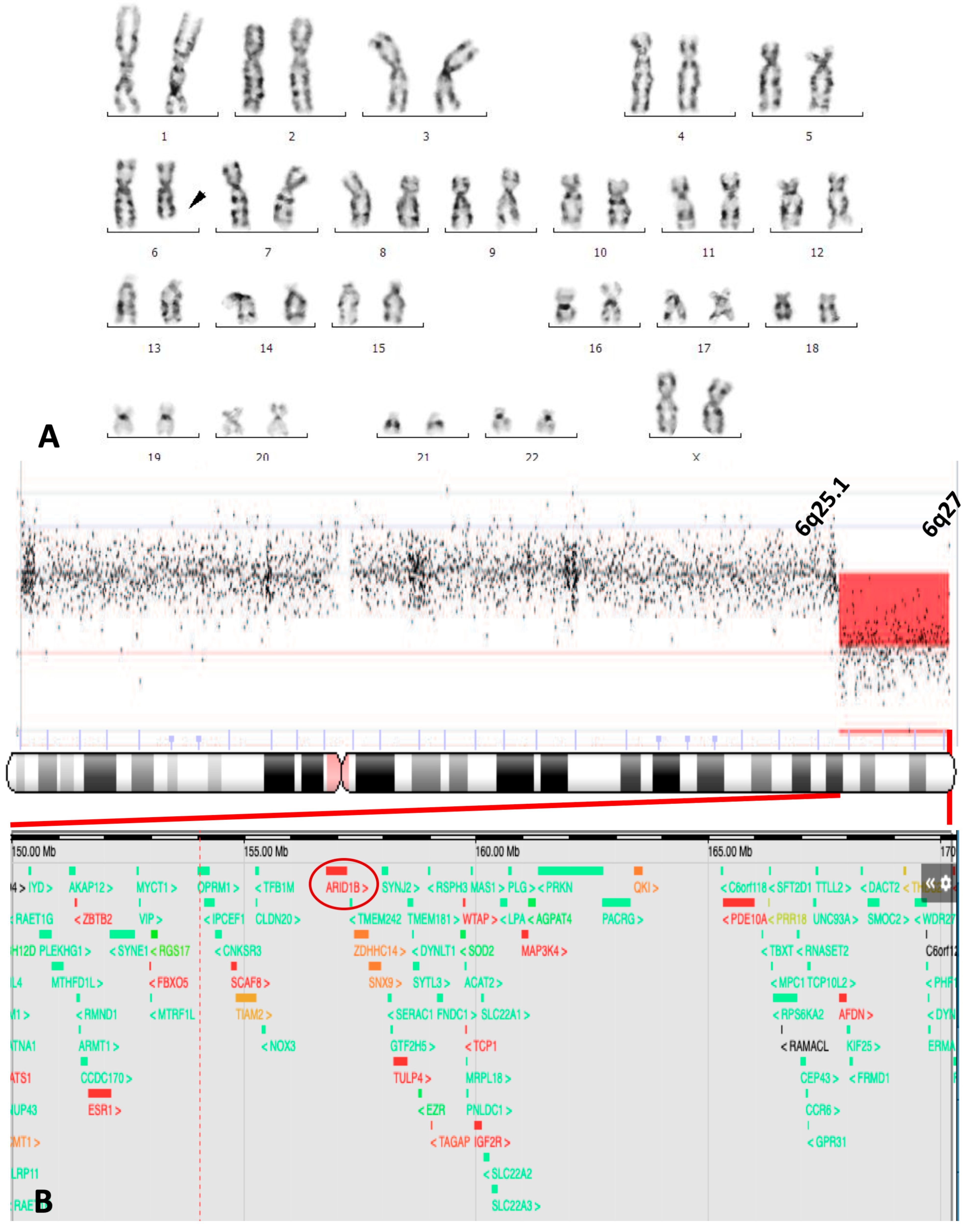

3. Case Report

4. Discussion

| Reference | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | [28] | [29] | [20] | [23] | [24] | [21] | [25] | [2] | [30] | [31] | [32] | [33] | Present Case | ||

| Patient | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| Sex | M | M | M | M | M | F | M | F | M | M | F | F | M | F | F |

| Age at last examination | 2 yr | 9 mo | 3 yr | 1 yr | 21 wk | Fetus | 4 mo | 2 yr | 10 yr | 2 yr | 37 yr | 9 yr | 10 mo | 18 mo | 3 mo |

| Prenatal findings | |||||||||||||||

| Intrauterine growth retardation | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | + | − |

| Cystic hygroma | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | + |

| Oligohydramnios | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | + | − |

| Ventriculomegaly | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | NS | − | + | − | − |

| Hydrops fetalis | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − |

| Hydrothorax | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − |

| Absent nasal bone | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | + |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − |

| Natal/postnatal findings | |||||||||||||||

| Birth length cm (percentile) | NS | NS | 51 (P50) | 48 (P60) | 23 (P25) | NS | 44 | NS | NS | 55.5 (P5) | NS | 49 (P50) | 47 (P1) | 48 | 41 (P10) |

| Birth weight g (percentile) | NS | 2670 (P1) | 3600 (P54) | 2870 (P60) | 280 (P10) | NS | 2220 | 1800 | NS | 2600 (P10) | NS | 2800 (P25) | 2800 (P3) | 2000 | 1840 (P16) |

| OFC at birth cm (percentile) | NS | NS | 35.5 (P50) | 32 (<P3) | 16 (P25) | NS | 30.8 | NS | NS | 44 (>P95) | NS | 34 (P50) | 31 (<P1) | 30 | 32 (P76) |

| Developmental delay/intellectual disability | + | + | + | + | NA | NA | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Microcephaly | Yes | + | + | + | − | NS | + | − | − | − | NS | − | + | + | − |

| Sparse scalp hair | − | + | − | − | NS | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Thick eyebrows | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| Long eyelashes | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | + | − | + |

| Dacryostenosis | − | − | − | NS | NS | − | − | − | NS | + | NS | − | − | − | − |

| Flat nasal bridge | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| Thick alae nasi | − | + | + | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Anteverted nose | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Long philtrum | + | + | + | + | + | NS | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | + |

| Large mouth | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Dysplastic ears | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hypertrichosis | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | NS | − | NS | − | + |

| Fifth fingernail aplasia/hypoplasia | − | − | − | + | − | NS | − | + * | − | NS | NS | − | − | − | + |

| Brachydactyly | + | − | − | − | − | NS | − | NS | No | NS | NS | − | − | + | + |

| Hemivertebrae | NS | NS | NS | NS | − | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | − | NS | NS | + |

| Congenital heart defects | |||||||||||||||

| Atrioventricular septal defect | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | NS | − | − | − | − |

| Ventricular septal defect | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | NS | − | − | + | + |

| Atrial septal defect | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | + | + | + |

| Partially anomalous pulmonary venous drainage | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − |

| Cor triatriatum | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − |

| Pulmonary vein stenosis | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | NS | − | − | − | − |

| Genitourinary anomalies | |||||||||||||||

| Hydronephrosis | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Duplicated collecting system | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Renal cyst | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Cryptorchidism | + | + | − | − | − | NA | + | NA | − | − | NA | NA | − | NA | NA |

| Penoscrotal webbing | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Clitoromegaly | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Prominent labia minora | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Cerebral dysgenesis | |||||||||||||||

| Corpus callosum agenesis (A)/hypoplasia | NS | NS | NS | −/− | +/− | −/− | +/− | −/− | NS | −/− | −/+ | −/+ | +/− | +/− | +/− |

| Ventriculomegaly/hydrocephaly | NS | NS | NS | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/− | NS | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| Colpocephaly | NS | NS | NS | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | + | + | + | − | − |

| Arhinencephaly | NS | NS | NS | − | + | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Cerebellar hypoplasia | NS | NS | NS | − | − | − | − | − | NS | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Other anomalies | HD, PrH | CP, HD | Cd | PrH | CP, DH | DH, SUA | AA, CP, PrT, STTh | TGC, RNS | − | EPi, RPi | S | − | S | − | RNS |

| Cytogenomic findings | |||||||||||||||

| Cytogenetic band deleted | 6q25 | 6q25 | 6q24 | 6q25 | 6q23 | 6q24.3 | 6q24.3 | 6q25.3 | 6q25 | 6q25.2 | 6q25.3 | 6q25.2 | 6q25.3 | 6q24 | 6q25.1 |

| ARID1B gene deletion | ? | ? | + | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CSS clinically recognizable | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASD | Atrial septal defect |

| CDH | Congenital diaphragmatic hernia |

| CH | Cystic hygroma |

| CHD | Congenital heart defect |

| CSS | Coffin–Siris syndrome |

| C6qDS | Chromosome 6q deletion syndrome |

| US | Ultrasound |

| VSD | Ventricular septal defect |

References

- Milosević, J.; Kalicanin, P. Long arm deletion of chromosome no. 6 in a mentally retarded boy with multiple physical malformations. J. Ment. Defic. Res. 1975, 19, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkin, R.J.; Schorry, E.; Bofinger, M.; Milatovich, A.; Stern, H.J.; Jayne, C.; Saal, H.M. New insights into the phenotypes of 6q deletions. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997, 70, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, R.; Mencarelli, M.; Papa, F.; Uliana, V.; Schiavone, S.; Strambi, M.; Pescucci, C.; Ariani, F.; Rossi, V.; Longo, I.; et al. A 2.6 Mb deletion of 6q24.3-25.1 in a patient with growth failure, cardiac septal defect, thin upperlip and asymmetric dysmorphic ears. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2007, 50, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, A.; Callier, P.; Masurel-Paulet, A.; Thauvin-Robinet, C.; Marle, N.; Nouchy, M.; Huet, F.; Dipanda, D.; De Paepe, A.; Coucke, P.; et al. Cytogenetic and array-CGH characterization of a 6q27 deletion in a patient with developmental delay and features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2010, 152A, 1314–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, J.C.; Neuhann, T.M.; Tyshchenko, N.; Smitka, M.; Hackmann, K. Expanding the clinical and neuroradiological phenotype of 6q27 microdeletion: Olfactory bulb aplasia and anosmia. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2011, 155, 1981–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigon, C.; Salviati, L.; Mandarano, R.; Donà, M.; Clementi, M. 6q27 subtelomeric deletions: Is there a specific phenotype? Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2011, 155, 1213–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowaczyk, M.J.; Carter, M.T.; Xu, J.; Huggins, M.; Raca, G.; Das, S.; Martin, C.L.; Schwartz, S.; Rosenfield, R.; Waggoner, D.J. Paternal deletion 6q24.3: A new congenital anomaly syndrome associated with intrauterine growth failure, early developmental delay and characteristic facial appearance. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2008, 146A, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddibhotla, S.; Nagamani, S.C.S.; Erez, A.; Hunter, J.V.; Holder, J.L., Jr.; Carlin, M.E.; Bader, P.I.; Perras, H.M.F.; Allanson, J.E.; Newman, L.; et al. Delineation of candidate genes responsible for structural brain abnormalities in patients with terminal deletions of chromosome 6q27. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 23, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, M.; Bronshtein, E.; Hankerd, M.; Adekola, H.; Puder, K.; Gonik, B.; Ebrahim, S. Genomic detection of a familial 382 Kb 6q27 deletion in a fetus with isolated severe ventriculomegaly and her affected mother. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2018, 176, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffin, G.S.; Siris, E. Mental retardation with absent fifth fingernail and terminal phalanx. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1970, 119, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santen, G.W.; Aten, E.; Sun, Y.; Almomani, R.; Gilissen, C.; Nielsen, M.; Kant, S.G.; Snoeck, I.N.; Peeters, E.A.J.; Hilhorst-Hofstee, Y.; et al. Mutations in SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex gene ARID1B cause Coffin-Siris syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 379–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurusaki, Y.; Okamoto, N.; Ohashi, H.; Kosho, T.; Imai, Y.; Hibi-Ko, Y.; Kaname, T.; Naritomi, K.; Kawame, H.; Wakui, K.; et al. Mutations affecting components of the SWI/SNF complex cause Coffin-Siris syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 376–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backx, L.; Seuntjens, E.; Devriendt, K.; Vermeesch, J.; Van Esch, H. A balanced translocation t(6;14)(q25.3;q13.2) leading to reciprocal fusion transcripts in a patient with intellectual disability and agenesis of corpus callosum. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2011, 132, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, M.; Ben-Sasson, A.; Vinkler, C.; Leshinsky-Silver, E.; Netzer, I.; Frumkin, A.; Kivity, S.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Lev, D. Delineation of the interstitial 6q25 microdeletion syndrome: Refinement of the critical causative region. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2012, 158A, 1395–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Sluijs, P.J.; Joosten, M.; Alby, C.; Attié-Bitach, T.; Gilmore, K.; Dubourg, C.; Fradin, M.; Wang, T.; Kurtz-Nelson, E.C.; Ahlers, K.P.; et al. Discovering a new part of the phenotypic spectrum of Coffin-Siris syndrome in a fetal cohort. Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan-Jordan, J.; Hastings, R.J.; Moore, S. (Eds.) ISCN 2020: An International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (2020); Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wadt, K.; Jensen, L.N.; Bjerglund, L.; Lundstrøm, M.; Kirchhoff, M.; Kjaergaard, S. Fetal ventriculomegaly due to familial submicroscopic terminal 6q deletions. Prenat. Diagn. 2012, 32, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eash, D.; Waggoner, D.; Chung, J.; Stevenson, D.; Martin, C.L. Calibration of 6q subtelomere deletions to define genotype/phenotype correlations. Clin. Genet. 2005, 67, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santen, G.W.; Aten, E.; Silfhout, A.T.V.-V.; Pottinger, C.; van Bon, B.W.; van Minderhout, I.J.; Snowdowne, R.; van der Lans, C.A.; Boogaard, M.; Linssen, M.M.; et al. Coffin-Siris syndrome and the BAF complex: Genotype-phenotype study in 63 patients. Hum. Mutat. 2013, 34, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, C.A.; Fineman, R.M.; Breg, W.R.; Silken, A.B. Report of two cases of distal deletion of the long arm of chromosome 6. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1988, 29, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Fujita, H.; Nagahara, N.; Kashiwai, A.; Yoshioka, Y.; Funato, M. Two patients with chromosome 6q terminal deletions with breakpoints at q24.3 and q25.3. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1992, 43, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulraj, P.; Palumbos, J.C.; Openshaw, A.; Carey, J.C.; Toydemir, R.M. Multiple Congenital Anomalies and Global Developmental Delay in a Patient with Interstitial 6q25.2q26 Deletion: A Diagnostic Odyssey. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2018, 156, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen-Schwarz, S.; Hill, L.M.; Surti, U.; Marchese, S. Deletion of terminal portion of 6q: Report of a case with unusual malformations. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1989, 32, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krassikoff, N.; Sekhon, G.S. Terminal deletion of 6q and Fryns syndrome: A microdeletion/syndrome pair? Am. J. Med. Genet. 1990, 36, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valtat, C.; Galliano, D.; Mettey, R.; Toutain, A.; Moraine, C. Monosomy 6q: Report on four new cases. Clin. Genet. 1992, 41, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, F.; Hecht, B.K. Nonrandom chromosome breakpoints in 6q deletions. Clin. Genet. 1992, 41, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denison, S.R.; Callahan, G.; Becker, N.A.; Phillips, L.A.; Smith, D.I. Characterization of FRA6E and its potential role in autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism and ovarian cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2003, 38, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoshesky, L.; Lewis, M.B.; Pashayan, H.M. Developmental abnormalities associated with long arm deletion of chromosome No. 6. Clin. Genet. 1978, 13, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, R.; Fish, B.; Ship, A.; Shprintzen, R.J. Deletion of a portion of the long arm of chromosome 6. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1980, 5, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striano, P.; Malacarne, M.; Cavani, S.; Pierluigi, M.; Rinaldi, R.; Cavaliere, M.L.; Rinaldi, M.M.; De Bernardo, C.; Coppola, A.; Pintaudi, M.; et al. Clinical phenotype and molecular characterization of 6q terminal deletion syndrome: Five new cases. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2006, 140, 1944–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, M.; Striano, P.; Fichera, M.; Gaggero, R.; Castiglia, L.; Galesi, O.; Malacarne, M.; Pierluigi, M.; Amato, C.; Musumeci, S.A.; et al. 6q terminal deletion syndrome associated with a distinctive EEG and clinical pattern: A report of five cases. Epilepsia 2006, 47, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamani, S.C.S.; Erez, A.; Eng, C.; Ou, Z.; Chinault, C.; Workman, L.; Coldwell, J.; Stankiewicz, P.; Patel, A.; Lupski, J.R.; et al. Interstitial deletion of 6q25.2–q25.3: A novel microdeletion syndrome associated with microcephaly, developmental delay, dysmorphic features and hearing loss. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 17, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, S.; Varghese, R.; Hashim, S.; Scariah, P. Dysmorphic features and congenital heart disease in chromosome 6q deletion: A short report. Indian J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 18, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peña-Padilla, C.; Martínez-Ceccopieri, D.A.; García-Hernández, E.M.; Bobadilla-Morales, L.; Corona-Rivera, J.R. Prenatal Diagnosis of 6q Terminal Deletion Associated with Coffin–Siris Syndrome: Phenotypic Delineation and Review. Genes 2025, 16, 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111365

Peña-Padilla C, Martínez-Ceccopieri DA, García-Hernández EM, Bobadilla-Morales L, Corona-Rivera JR. Prenatal Diagnosis of 6q Terminal Deletion Associated with Coffin–Siris Syndrome: Phenotypic Delineation and Review. Genes. 2025; 16(11):1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111365

Chicago/Turabian StylePeña-Padilla, Christian, David Alejandro Martínez-Ceccopieri, Evelin Montserrat García-Hernández, Lucina Bobadilla-Morales, and Jorge Román Corona-Rivera. 2025. "Prenatal Diagnosis of 6q Terminal Deletion Associated with Coffin–Siris Syndrome: Phenotypic Delineation and Review" Genes 16, no. 11: 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111365

APA StylePeña-Padilla, C., Martínez-Ceccopieri, D. A., García-Hernández, E. M., Bobadilla-Morales, L., & Corona-Rivera, J. R. (2025). Prenatal Diagnosis of 6q Terminal Deletion Associated with Coffin–Siris Syndrome: Phenotypic Delineation and Review. Genes, 16(11), 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111365