Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis Reveals Key Regulatory Genes and Therapeutic Targets in Ulcerative Colitis Pathogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection for Gene Expression Profiles

2.2. Screening and Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

2.3. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Analysis

2.4. Identification of Hub Genes

2.5. Gene Enrichment Analysis

2.6. Gene–miRNA–TF Interaction Network

2.7. Gene–Disease Association Analysis

2.8. Protein–Drug Interaction Analysis

2.9. Molecular Docking

2.10. ADME/T Prediction

3. Results

3.1. Identification of DEGs

3.2. Common Gene Identification and PPI Construction

3.3. Identification of Hub Genes

3.4. Gene Ontology (GO) and Pathways Enrichment Analysis

3.5. Identification of Gene Regulators

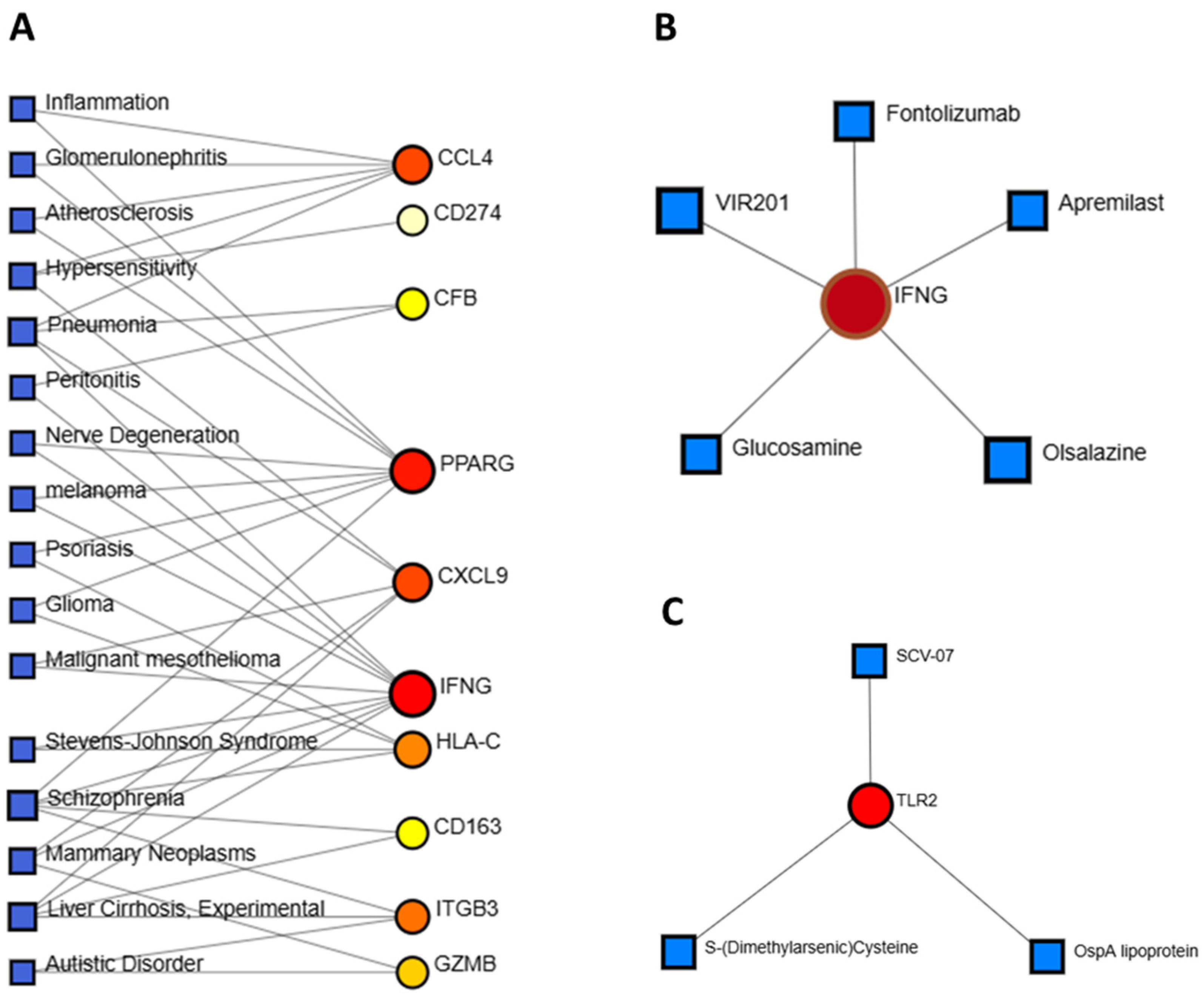

3.6. Identification of Disease Associations and Drug Candidates

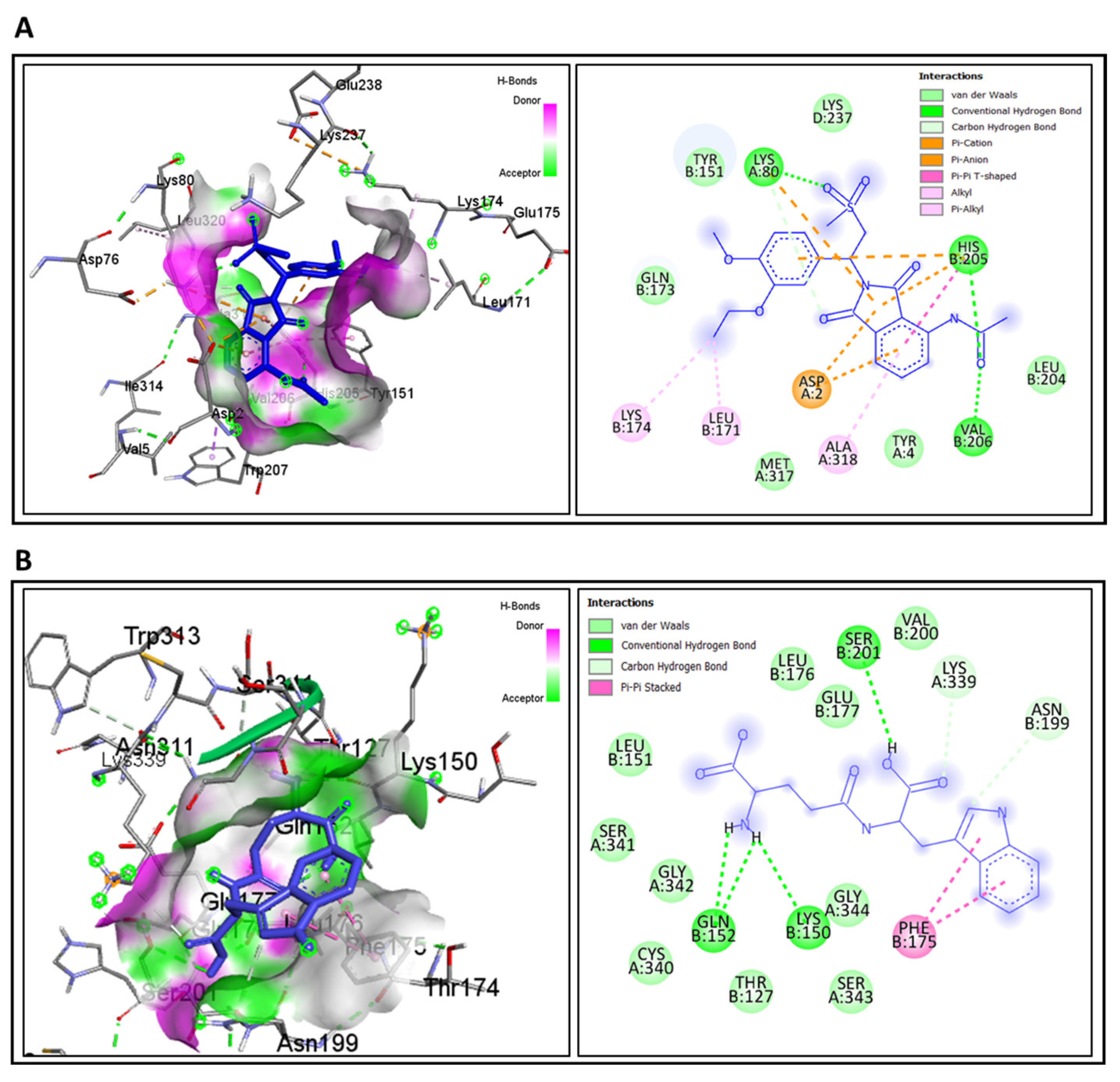

3.7. Molecular Docking for Drug Repurposing and ADME/T Profiling

4. Discussion

| Category | Validated UC/Treatment Markers (Previous Studies) | Functional Role in UC | Hub Genes Identified in This Study | Functional Role in UC (This Study) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic/Disease Activity | Calprotectin (S100A8/A9) [41], C-reactive protein (CRP) [41] | Clinical biomarkers widely used for inflammation and disease monitoring | CD163 | Scavenger receptor on macrophages; associated with anti-inflammatory modulation, fibrosis, and impaired tissue repair [49,50] |

| Genetic Predisposition/Barrier Integrity | HNF4A, ICAM1, RNF186 [14,16] | Regulate epithelial barrier integrity, immune modulation, and genetic susceptibility to UC | TLR2 | Recognizes microbial ligands; initiates innate immune responses; dysregulation activates NF-κB and exacerbates mucosal inflammation [45,46,47] |

| Inflammation/Immune Signaling | Oncostatin M (OSM) [39], TNF-α, IL-6 [47] | Pro-inflammatory mediators; OSM predicts anti-TNF therapy resistance | IFNG | Key cytokine driving macrophage activation, T-cell infiltration, and chronic inflammation in UC [47,48] |

| Therapeutic Implications | Anti-TNF response markers (e.g., OSM, CRP) [39,41] | Guide biologic therapy decisions | Apremilast, Golotimod (predicted drug–gene interactions) | Target IFNG and TLR2; potential drug repurposing candidates with favorable ADME/T properties [67,68,69] |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| BP | Biological process |

| CC | Cellular component |

| MF | Molecular function |

| DEG | Differentially expressed gene |

| ENCODE | Encyclopedia of DNA Elements |

| TF | Transcription factors |

| miRNA | micro RNA |

| IFNG | Interferon-gamma |

| TLR2 | Toll-like receptor 2 |

| FOXC1 | Forkhead Box C1 |

| GABPA | GA-binding protein alpha chain |

| GATA2 | GATA Binding Protein 2 |

| SUPT5H | Transcription elongation factor SPT5 |

| GRN | Gene regulatory network |

References

- Conrad, K.; Roggenbuck, D.; Laass, M.W. Diagnosis and Classification of Ulcerative Colitis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014, 13, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.L.; van Langenberg, D.R.; Taylor, K.M.; Gibson, P.R. Characterization of Ulcerative Colitis—Associated Constipation Syndrome (Proximal Constipation). JGH Open 2018, 2, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindryckx, P.; Jairath, V.; D’Haens, G. Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, H. Crohn’s Disease and Environmental Factors in the New Zealand Context: A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctoral of Philosophy. Ph.D. Thesis, Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Dulai, P.S. Ulcerative Colitis: Clinical Manifestations and Management. In Yamada’s Textbook of Gastroenterology; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 3, pp. 1248–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Rogler, G. Chronic Ulcerative Colitis and Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014, 345, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashiro, M. Ulcerative Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 16389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jess, T.; Gamborg, M.; Munkholm, P.; Sørensen, T.I.A. Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality in Ulcerative Colitis: Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Inception Cohort Studies. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumery, M.; Singh, S.; Dulai, P.S.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Sandborn, W.J. Natural History of Adult Ulcerative Colitis in Population-Based Cohorts: A Systematic Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 343–356.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiong, J.; Ding, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, P. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Burden in Asia from 1990 to 2019 and Predictions to 2040. Medrxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Kotze, P.G.; Spinelli, A. Surgery in Ulcerative Colitis: When? How? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 32, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakase, H. Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis: Optimal Strategies for Drug Therapy. Gut Liver 2023, 17, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedano, R.; Quera, R.; Simian, D.; Yarur, A.J. An Approach to Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 13, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Zeng, F.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y. Identification of Differential Intestinal Mucosa Transcriptomic Biomarkers for Ulcerative Colitis by Bioinformatics Analysis. Dis. Markers 2020, 2020, 8876565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zeng, Y.; Wen, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y. Natural Products Modulate Cell Apoptosis: A Promising Way for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 806148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zou, M.; Fu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Autophagy: A Potential Target for Natural Products in the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahi, N.A.; Najafabadi, M.F.; Pilarczyk, M.; Kouril, M.; Medvedovic, M. GREIN: An Interactive Web Platform for Re-Analyzing GEO RNA-Seq Data. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüleci, H.B.; Uzuner, D.; Cesur, M.F.; İlgün, A.; Düz, E.; Abdik, E.; Odongo, R.; Çakır, T. A benchmark of RNA-seq data normalization methods for transcriptome mapping on human genome-scale metabolic networks. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 2024, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y. Venn Diagrams in Bioinformatics. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbab108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Pamplona, R.; Berenguer, A.; Sole, X.; Cordero, D.; Crous-Bou, M.; Serra-Musach, J.; Guinó, E.; Pujana, M.Á.; Moreno, V. Tools for Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis in Cancer Research. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2012, 14, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, R.; Dai, T.; Guo, Y.; Tian, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, J.; Yu, Y. Identification of Hub Genes and Key Pathways in Arsenic-Treated Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Based on 9 Topological Analysis Methods of CytoHubba. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2024, 29, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, C.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Wu, H.-H.; Ho, C.-W.; Ko, M.-T.; Lin, C.-Y. CytoHubba: Identifying Hub Objects and Sub-Networks from Complex Interactome. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, B.T.; Hao, M.; Qiu, J.; Jiao, X.; Baseler, M.W.; Lane, H.C.; Imamichi, T.; Chang, W. DAVID: A Web Server for Functional Enrichment Analysis and Functional Annotation of Gene Lists (2021 Update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W216–W221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; Rana, R.; Chhabra, A.; Jaiswal, A.; Rani, V. MiRNA–Transcription Factor Interactions: A Combinatorial Regulation of Gene Expression. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2013, 288, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercatelli, D.; Scalambra, L.; Triboli, L.; Ray, F.; Giorgi, F.M. Gene Regulatory Network Inference Resources: A Practical Overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 2020, 1863, 194430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykes, I.M.; Emanueli, C. Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation by Long Non-Coding RNA. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2017, 15, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Soufan, O.; Ewald, J.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Basu, N.; Xia, J. NetworkAnalyst 3.0: A Visual Analytics Platform for Comprehensive Gene Expression Profiling and Meta-Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W234–W241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñero, J.; Ramírez-Anguita, J.M.; Saüch-Pitarch, J.; Ronzano, F.; Centeno, E.; Sanz, F.; Furlong, L.I. The DisGeNET Knowledge Platform for Disease Genomics: 2019 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, D845–D855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Feunang, Y.D.; Guo, A.C.; Lo, E.J.; Marcu, A.; Grant, J.R.; Sajed, T.; Johnson, D.; Li, C.; Sayeeda, Z.; et al. DrugBank 5.0: A Major Update to the DrugBank Database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1074–D1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth Huey, G.M.M.S.F. Using AutoDock 4 and AutoDock Vina with AutoDockTools: A Tutorial. Scripps Res. Inst. Mol. Graph. Lab. 2012, 10550, 1000. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Adedoyin, A. ADME–Tox in Drug Discovery: Integration of Experimental and Computational Technologies. Drug Discov. Today 2003, 8, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. PkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, T.G.O. Creating the Gene Ontology Resource: Design and Implementation. Genome Res. 2001, 11, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gren, S.T.; Grip, O. Role of Monocytes and Intestinal Macrophages in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, H.; Kayama, H.; Nishimura, J.; Sekido, Y.; Osawa, H.; Barman, S.; Ogino, T.; Takahashi, H.; Haraguchi, N.; Hata, T.; et al. CD103+ Dendritic Cell Function Is Altered in the Colons of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1524–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Lin, K.; Fang, J.; Chen, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, F. Pyroptosis-Related Signature Predicts the Progression of Ulcerative Colitis and Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer as Well as the Anti-TNF Therapeutic Response. J. Immunol. Res. 2023, 2023, 7040113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minar, P.; Lehn, C.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Jackson, K.; Rosen, M.J.; Denson, L.A. Elevated Pretreatment Plasma Oncostatin M Is Associated With Poor Biochemical Response to Infliximab. Crohn’s Colitis 360 2019, 1, otz026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim Sacramento, L.; Farias Amorim, C.; G. Lombana, C.; Beiting, D.; Novais, F.; P. Carvalho, L.; M. Carvalho, E.; Scott, P. CCR5 Promotes the Migration of Pathological CD8+ T Cells to the Leishmanial Lesions. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Lu, J.; Francis, J.D.; Moore, R.E.; Haley, K.P.; Doster, R.S.; Townsend, S.D.; Johnson, J.G.; Damo, S.M.; Gaddy, J.A. S100A12 in Digestive Diseases and Health: A Scoping Review. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2020, 2868373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhen, D.; Gao, Z. Combined Bulk and Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis to Reveal the Potential Influences of Intestinal Inflammatory Disease on Multiple Sclerosis. Inflammation 2024, 48, 2367–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valoti, E. Genetic Factors Associated with Anti-Factor H Autoantibodies in Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (AHUS). Ph.D. Thesis, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chamier-Gliszczyńska, A.; Brązert, M.; Sujka-Kordowska, P.; Popis, M.; Ożegowska, K.; Stefańska, K.; Kocherova, I.; Celichowski, P.; Kulus, M.; Bukowska, D.; et al. Genes Involved in Angiogenesis and Circulatory System Development Are Differentially Expressed in Porcine Epithelial Oviductal Cells during Long-Term Primary in Vitro Culture—A Transcriptomic Study. Med. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 6, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R. Toll-like Receptors and Innate Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 1, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasselon, T.; Detmers, P.A. Toll Receptors: A Central Element in Innate Immune Responses. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatiya-Aphiradee, N.; Chatuphonprasert, W.; Jarukamjorn, K. Immune Response and Inflammatory Pathway of Ulcerative Colitis. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kak, G.; Raza, M.; Tiwari, B.K. Interferon-Gamma (IFN-γ): Exploring Its Implications in Infectious Diseases. Biomol. Concepts 2018, 9, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzerodt, A.; Moestrup, S.K. CD163 and Inflammation: Biological, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Aspects. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2013, 18, 2352–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, H.; Chen, K.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Ran, T.; Zou, D. Intestinal Fibrosis Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Known and Unknown. Chin. Med. J. 2025, 138, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocansey, D.K.W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Qian, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Mao, F. Exosome-mediated Effects and Applications in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1287–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yang, M.; Xu, J.; Xu, H.; Zhu, M.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, C.; Nie, Y.; Shi, R.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles: The Next Generation Theranostic Nanomedicine for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 3893–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lee, C.; Yu, Z.; Chen, C.; Liang, C. Ulcerative Colitis: Molecular Insights and Intervention Therapy. Mol. Biomed. 2024, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałużna, A.; Olczyk, P.; Komosińska-Vassev, K. The Role of Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells in the Pathogenesis and Development of the Inflammatory Response in Ulcerative Colitis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Ye, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Ding, L.; Liu, Y.; Luo, L.; Wei, L.; Chen, J.; Bian, Z. Glaucocalyxin A Alleviates Ulcerative Colitis by Inhibiting PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Xue, T.; Wang, B.; Guo, H.; Liu, Q. Chinese Medicine in the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis: The Mechanisms of Signaling Pathway Regulations. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2022, 50, 1781–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, R.; Nandani, R.; Pandey, R.K.; Mishra, A.; Prajapati, V.K. Emerging Role of Circulating MicroRNA in the Diagnosis of Human Infectious Diseases. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 1030–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauensteiner, J.; Bertinat, R.; León, L.E.; Riederer, M.; Sepúlveda, N.; Westermeier, F. Altered Endothelial Dysfunction-Related MiRs in Plasma from ME/CFS Patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xie, M.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J.; Huang, C. Identification and Interaction Analysis of Key Genes and MicroRNAs in Systemic Sclerosis by Bioinformatics Approaches. Curr. Med. Sci. 2019, 39, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ni, Z.; Li, Z. Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 and Selectin l Play Crucial Roles in Ulcerative Colitis. Medicine 2023, 102, e36552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, S.; Polo, A.; Ariano, A.; Velotto, S.; Costantini, S.; Severino, L. Aflatoxin B1 and M1: Biological Properties and Their Involvement in Cancer Development. Toxins 2018, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Pang, D.; Zhou, L.; Ouyang, H.; Tian, Y.; Yu, H. MiR-26a-5p Inhibits the Proliferation of Psoriasis-like Keratinocytes in Vitro and in Vivo by Dual Interference with the CDC6/CCNE1 Axis. Aging 2024, 16, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Do, D.N.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Nguyen, T.L.; Nguyen-Thanh, T.; Nguyen, H.T. Immune–Related Biomarkers Shared by Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Liver Cancer. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A. The Role of Estrogen-Related Receptor Alpha (ERRα) in Intestinal Homeostasis and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Master’s Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, D.F.; Barrett, N.A.; Austen, K.F. Expression Profiling of Constitutive Mast Cells Reveals a Unique Identity within the Immune System. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, N.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Feng, Y.; Hsieh, W.-C.; Song, J.-S.; Lin, Y.-S.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Liao, W.-J.; Chu, Y.-F.; Liu, Y.-C.; et al. Chemical Interference with DSIF Complex Formation Lowers Synthesis of Mutant Huntingtin Gene Products and Curtails Mutant Phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2204779119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Kaur, S.; Rana, R.; Kumar, B.; Melkani, I.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N.K.; Joshi, K.; Patel, D.; Porwal, O. Pathogenesis, Molecular Mechanism and Treatment Approaches of Psoriasis: An Update. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2024; p. 030051. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, A.; Besser, M.; Broichhausen, S.; Winter, M.; Bungert, A.D.; Strücker, B.; Juratli, M.A.; Pascher, A.; Becker, F. The Influence of Apremilast-Induced Macrophage Polarization on Intestinal Wound Healing. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Tang, J. Intestinal Infection of Candida Albicans: Preventing the Formation of Biofilm by C. Albicans and Protecting the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 783010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GEO Accession No | Source of Sample | Total Sample Size | Control Sample | Case Sample | Experiment Type | Total DEGs | Up-Regulated DEGs | Down- Regulated DEGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE135223 | Colon, Macrophages | 10 | 5 | 5 | Stranded RNA sequencing | 2340 | 1279 | 1061 |

| GSE112057 | Colon, Macrophages, small bowel | 27 | 12 | 15 | Stranded RNA sequencing | 1526 | 905 | 621 |

| GSE83687 | Colon, rectum, small bowel | 92 | 60 | 32 | Stranded RNA sequencing | 2759 | 1512 | 1247 |

| Biological Process | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Name | ID | p-Value | Enrichment | Number of Genes Involved | Benjamini | FDR < 0.05 |

| Innate Immune response | GO:0045087 | 4.73 × 10−09 | 14.38849 | 20 | 2.43 × 10−06 | 2.37 × 10−06 |

| Signal transduction | GO:0007165 | 9.97 × 10−04 | 14.38849 | 20 | 0.040968 | 0.040051 |

| Inflammatory response | GO:0006954 | 3.28 × 10−10 | 13.66906 | 19 | 3.37 × 10−07 | 3.29 × 10−07 |

| Immune response | GO:0006955 | 4.41 × 10−05 | 10.07194 | 14 | 0.005413 | 0.005292 |

| CSR signaling pathway | GO:0007166 | 3.37 × 10−06 | 9.352518 | 13 | 8.94 × 10−04 | 8.74 × 10−04 |

| Cellular component | ||||||

| Plasma membrane | GO:0005886 | 4.14 × 10−10 | 50.35971 | 70 | 4.12 × 10−08 | 3.85 × 10−08 |

| Membrane | GO:0016020 | 1.06 × 10−04 | 40.28777 | 56 | 0.002001 | 0.00187 |

| Extracellular region | GO:0005576 | 2.49 × 10−10 | 30.21583 | 42 | 4.12 × 10−08 | 3.85 × 10−08 |

| Extracellular space | GO:0005615 | 1.41 × 10−09 | 27.33813 | 38 | 9.36 × 10−08 | 8.75 × 10−08 |

| Extracellular exosome | GO:0070062 | 8.55 × 10−04 | 20.14388 | 28 | 0.011349 | 0.010608 |

| Molecular Function | ||||||

| Calcium ion binding | GO:0005509 | 0.004742 | 9.352518 | 13 | 0.13474 | 0.131579 |

| Carbohydrate binding | GO:0030246 | 5.12 × 10−04 | 5.755396 | 8 | 0.058147 | 0.056782 |

| Transmembrane signaling RA | GO:0004888 | 0.001923 | 5.035971 | 7 | 0.098729 | 0.096412 |

| Serine-type EA | GO:0004252 | 0.002027 | 5.035971 | 7 | 0.098729 | 0.096412 |

| Signaling receptor activity | GO:0038023 | 0.004322 | 5.035971 | 7 | 0.13474 | 0.131579 |

| KEGG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Name | ID | p-Value | Enrichment | Number of Genes Involved | Benjamini | FDR < 0.05 |

| Osteoclast differentiation | hsa04380 | 3.80 × 10−07 | 7.913669 | 11 | 6.80 × 10−05 | 6.34 × 10−05 |

| Phagosome | hsa04145 | 6.62 × 10−05 | 6.47482 | 9 | 0.0059204 | 0.005524 |

| PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | hsa04151 | 0.012915 | 6.47482 | 9 | 0.151348233 | 0.141202 |

| Herpes simplex virus 1 infection | hsa05168 | 0.082924 | 6.47482 | 9 | 0.549757891 | 0.512903 |

| Transcriptional mis regulation in cancer | hsa05202 | 0.007328 | 5.035971 | 7 | 0.1293794 | 0.120706 |

| Reactome Pathways | ||||||

| Immune System | R-HSA-168256 | 3.94 × 10−14 | 38.84892 | 54 | 9.47 × 10−12 | 9.35 × 10−12 |

| Innate Immune System | R-HSA-168249 | 8.31 × 10−12 | 25.89928 | 36 | 1.33 × 10−09 | 1.32 × 10−09 |

| Neutrophil degranulation | R-HSA-6798695 | 1.80 × 10−14 | 20.14388 | 28 | 8.66 × 10−12 | 8.55 × 10−12 |

| Adaptive Immune System | R-HSA-1280218 | 0.004189 | 11.51079 | 16 | 0.201481011 | 0.198968 |

| Cytokine Signaling in Immune system | R-HSA-1280215 | 0.027725 | 10.07194 | 14 | 0.514440567 | 0.508023 |

| WikiPathways | ||||||

| Focal adhesion PI3K Akt mTOR signaling | WP3932 | 0.005393 | 6.47482 | 13 | 0.190108 | 0.186063 |

| PI3K Akt signaling | WP4172 | 0.01035 | 6.47482 | 13 | 0.291878 | 0.285668 |

| Complement system | WP2806 | 2.01 × 10−05 | 5.755396 | 12 | 0.005662 | 0.005541 |

| Network map of SARS CoV 2 signaling | WP5115 | 0.025447 | 5.035971 | 12 | 0.598015 | 0.585291 |

| Allograft rejection | WP2328 | 0.001205 | 4.316547 | 8 | 0.068002 | 0.066555 |

| Name of Potential Targets (PDB ID) | “Name” and Compound ID of Drugs (2 Control Drugs) | Docking Score of Controls (Kcal/mol) | Docking Score of Drugs (Kcal/mol) | Amino Acids Interaction of Drugs | Number of Total Bonds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond | Hydrophobic Bond | |||||

| IFNG (IFYH) | “Apremilast” CID: 11561674 Mesalamine CID: 4075 Azathioprine CID: 2265 | −5.2 −5.8 | −8.3 | LYS A: 80, LYS D: 237, TYR B: 151, HIS B: 205, VAL B: 206, LEU B: 204, TYR A: 4, MET A:317, GLN B:173 | LYS B: 174, LEU B: 171, ALA A: 318, ASP A: 2 | 13 |

| TLR2 (2Z80) | “Golotimod” CID:6992140 (Mesalamine CID: 4075) (Azathioprine CID: 2265) | −5.9 −6.7 | −7.6 | VAL B: 200, SER B: 201, GLN B: 152, LYS B:150, LEU B: 176, GLU B: 177, LEU B: 151, SER A: 341, GLY A:342, CYS A:340, THR B:127, GLY A:344. SER A: 343 | LYS A: 339, ASN B: 199, PHE B: 175 | 16 |

| Properties | Compound:01 CID:11561674 (Apremilast) | Compound:02 CID:6992140 (Golotimod) | Control: 01 CID: 4075 (Mesalamine) | Control:2 CID:2265 (Azathioprine) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Properties | MW (g/mol) | 460.50 | 333.34 | 153.14 | 277.26 |

| Heavy atoms | 32 | 24 | 11 | 19 | |

| Rotatable bonds | 9 | 9 | 6 | 14 | |

| H-bond acceptors | 7 | 6 | 3 | 6 | |

| H-bond donors | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.55 | |

| PAINS | no alert | no alert | No alert | No alert | |

| Drug likeness | Lipinski | Yes; no violation | Yes; no violation | Yes; no violation | Yes; no violation |

| Absorption | Water solubility ((log mol/L)) | −4.462 | −2.892 | −2.109 | −2.891 |

| Caco2 permeability (log Papp in 10−6 cm/s) | 0.205 | −0.662 | 0.601 | 0.616 | |

| Intestinal absorption (% Absorbed) | 83.793 | 56.004 | 79.024 | 78.64 | |

| Skin Permeability (log Kp) | −2.761 | −2.735 | −2.735 | −2.735 | |

| Distribution | VDss (log L/kg) | −0.386 | −0.05 | −1.629 | 0.138 |

| BBB permeability (log BB) | −0.573 | −1.028 | −0.6 | −1.227 | |

| CNS permeability (log PS) | −2.44 | −3.496 | −3.306 | −3.509 | |

| Metabolism | CYP2D6 substrate | No | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 substrate | Yes | No | No | No | |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Excretion | Total Clearance | 0.227 | 0.595 | 0.49 | 0.148 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate | No | No | No | No | |

| Toxicity | AMES toxicity | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Max. tolerated dose (log mg/kg/day) | 0.042 | 0.738 | 1.153 | 0.491 | |

| Skin Sensitization | No | No | No | No | |

| Oral Rat Acute Toxicity (LD50) (mol/kg) | 2 | 2.477 | 1.809 | 2.486 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahman, S.A.; Khatun, M.T.; Singh, M.; Biswas, V.K.; Hoque, F.; Zaman, N.N.; Parvin, A.; Uddin, M.K.M.; Sheikh, M.M.I.; Begum, M.M.; et al. Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis Reveals Key Regulatory Genes and Therapeutic Targets in Ulcerative Colitis Pathogenesis. Genes 2025, 16, 1296. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111296

Rahman SA, Khatun MT, Singh M, Biswas VK, Hoque F, Zaman NN, Parvin A, Uddin MKM, Sheikh MMI, Begum MM, et al. Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis Reveals Key Regulatory Genes and Therapeutic Targets in Ulcerative Colitis Pathogenesis. Genes. 2025; 16(11):1296. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111296

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahman, Sheikh Atikur, Mst. Tania Khatun, Mahendra Singh, Viplov Kumar Biswas, Forkanul Hoque, Nurun Nesa Zaman, Anzana Parvin, Mohammad Khaja Mafij Uddin, Md. Mominul Islam Sheikh, Most Morium Begum, and et al. 2025. "Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis Reveals Key Regulatory Genes and Therapeutic Targets in Ulcerative Colitis Pathogenesis" Genes 16, no. 11: 1296. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111296

APA StyleRahman, S. A., Khatun, M. T., Singh, M., Biswas, V. K., Hoque, F., Zaman, N. N., Parvin, A., Uddin, M. K. M., Sheikh, M. M. I., Begum, M. M., Arya, R., & Faruquee, H. M. (2025). Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis Reveals Key Regulatory Genes and Therapeutic Targets in Ulcerative Colitis Pathogenesis. Genes, 16(11), 1296. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111296