Analysis of SNHG14: A Long Non-Coding RNA Hosting SNORD116, Whose Loss Contributes to Prader–Willi Syndrome Etiology

Abstract

1. Introduction

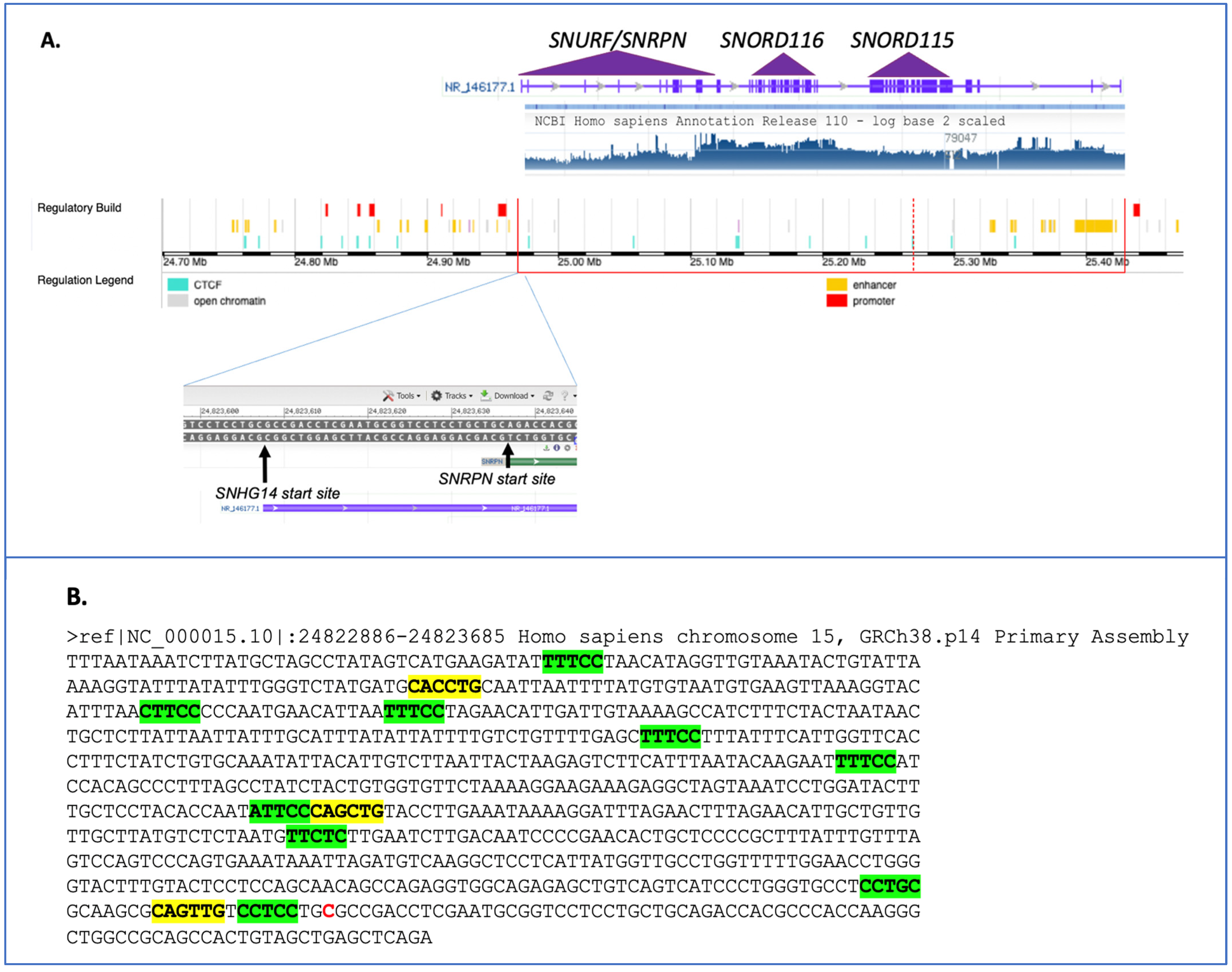

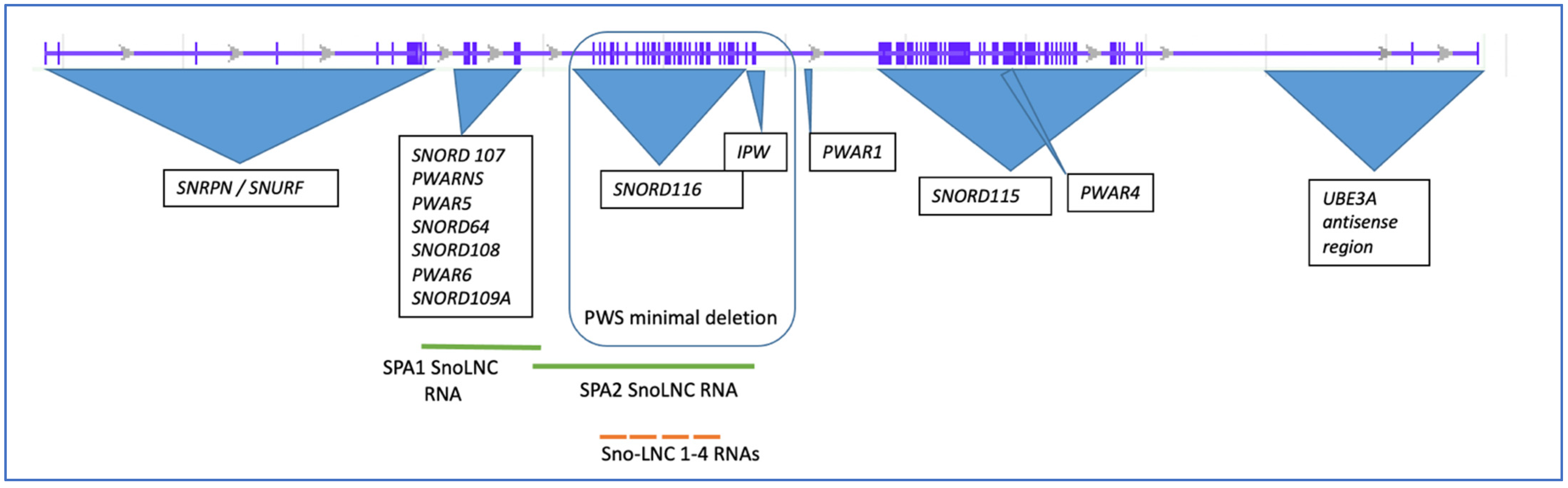

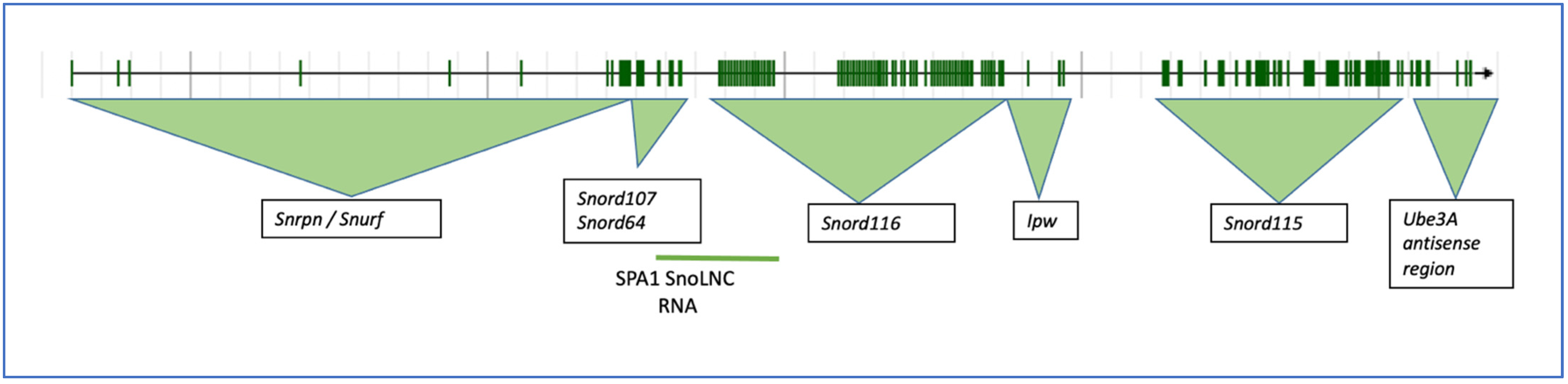

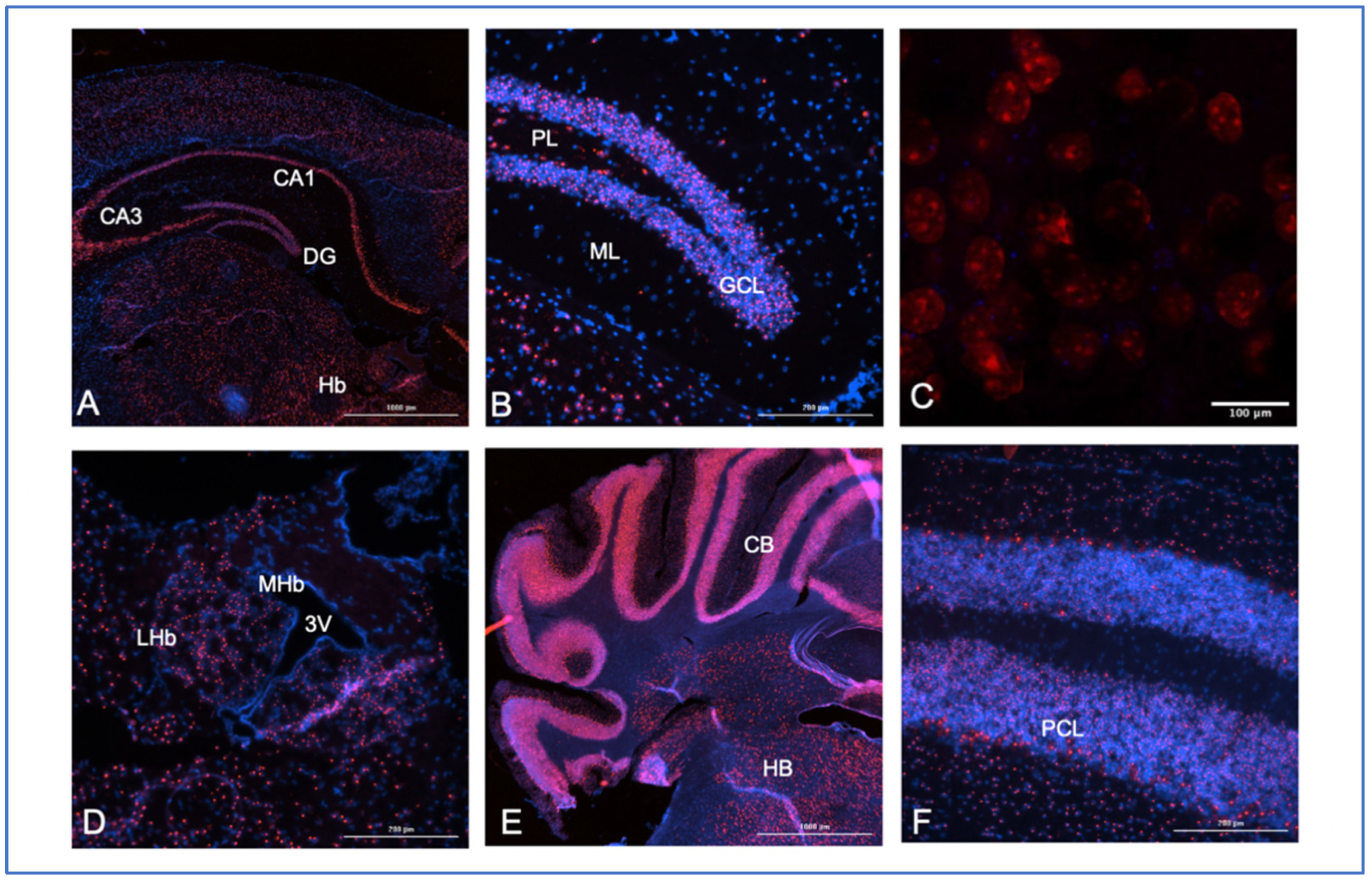

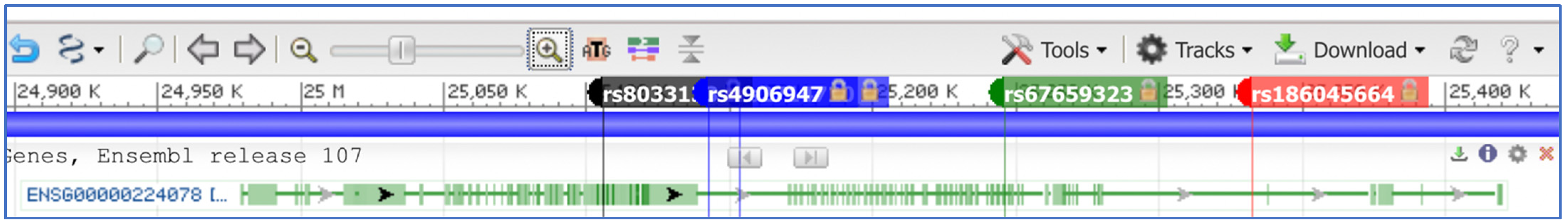

2. The SNHG14 Locus

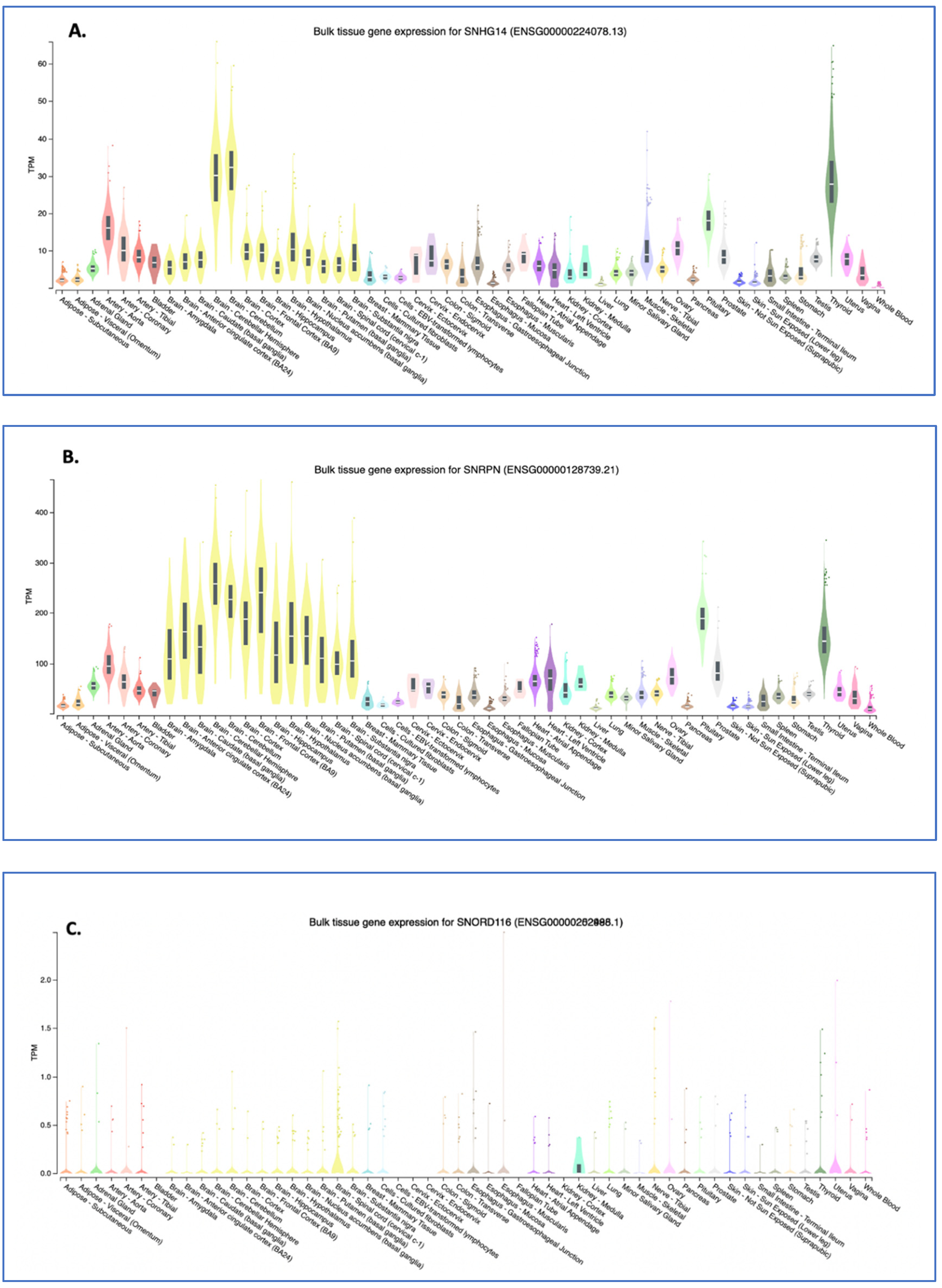

3. Expression of SNHG14 RNA

4. Single Nucleotide Variant Analysis in SNHG14 and Its Hosted Transcripts

5. Concluding Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cunningham, F.; Allen, J.E.; Allen, J.; Alvarez-Jarreta, J.; Amode, M.R.; Armean, I.M.; Austine-Orimoloye, O.; Azov, A.G.; Barnes, I.; Bennett, R.; et al. Ensembl 2022. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2022, 50, D988–D995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Yang, L.Z.; Chen, L.L. Long noncoding RNA and protein abundance in lncRNPs. RNA 2021, 27, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, F.; Mendell, J.T. Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2018, 172, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rougeulle, C.; Cardoso, C.; Fontes, M.; Colleaux, L.; Lalande, M. An imprinted antisense RNA overlaps UBE3A and a second maternally expressed transcript. Nat. Genet. 1998, 19, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, S.L.; Bhatt, N.K.; Martin, S.A.; Sutcliffe, J.S.; Kubota, T.; Huang, B.; Mutirangura, A.; Chinault, A.C.; Beaudet, A.L.; Ledbetter, D.H. Integrated YAC contig map of the Prader-Willi/Angelman region on chromosome 15q11-q13 with average STS spacing of 35 kb. Genome. Res. 1998, 8, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cavaille, J.; Buiting, K.; Kiefmann, M.; Lalande, M.; Brannan, C.I.; Horsthemke, B.; Bachellerie, J.P.; Brosius, J.; Huttenhofer, A. Identification of brain-specific and imprinted small nucleolar RNA genes exhibiting an unusual genomic organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 14311–14316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runte, M.; Huttenhofer, A.; Gross, S.; Kiefmann, M.; Horsthemke, B.; Buiting, K. The IC-SNURF-SNRPN transcript serves as a host for multiple small nucleolar RNA species and as an antisense RNA for UBE3A. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 2687–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaille, J. Box C/D small nucleolar RNA genes and the Prader-Willi syndrome: A complex interplay. Wiley Int. Rev. RNA 2017, 8, e1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.F.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, J.F.; Wu, Y.W.; Carmichael, G.G.; Chen, L.L. Long noncoding RNAs with snoRNA ends. Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yin, Q.F.; Luo, Z.; Yao, R.W.; Zheng, C.C.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, J.F.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.L. Unusual Processing Generates SPA LncRNAs that Sequester Multiple RNA Binding Proteins. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringwald, M.; Richardson, J.E.; Baldarelli, R.M.; Blake, J.A.; Kadin, J.A.; Smith, C.; Bult, C.J. Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI): Latest news from MGD and GXD. Mamm. Genome. 2022, 33, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D.J.; Kocher, M.A. Phylogenetic Analysis of the SNORD116 Locus. Genes 2017, 8, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiveti, C.R.; Raabe, C.A.; Konthur, Z.; Rozhdestvensky, T.S. Differential regulation of non-protein coding RNAs from Prader-Willi Syndrome locus. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Wu, M.; Ma, Q. The Role of Long Non-coding RNAs in Human Imprinting Disorders: Prospective Therapeutic Targets. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 730014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootjen, L.N.; Juriaans, A.F.; Kerkhof, G.F.; Hokken-Koelega, A.C.S. Atypical 15q11.2-q13 Deletions and the Prader-Willi Phenotype. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandstrat, A.E.; Leana-Cox, J.; Jenkins, L.; Schwartz, S. Molecular cytogenetic evidence for a common breakpoint in the largest inverted duplications of chromosome 15. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998, 62, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, L.R.; Barber, G.P.; Benet-Pages, A.; Casper, J.; Clawson, H.; Diekhans, M.; Fischer, C.; Gonzalez, J.N.; Hinrichs, A.S.; Lee, B.T.; et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2023 update. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2022, gkac1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Crolla, J.A.; Christian, S.L.; Wolf-Ledbetter, M.E.; Macha, M.E.; Papenhausen, P.N.; Ledbetter, D.H. Refined molecular characterization of the breakpoints in small inv dup(15) chromosomes. Hum. Genet. 1997, 99, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Mitsuhashi, S.; Miyake, N.; Ohta, T.; Liang, D.; Wu, L.; Matsumoto, N. Translocation breakpoint disrupting the host SNHG14 gene but not coding genes or snoRNAs in typical Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 64, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, T.; Gray, T.A.; Rogan, P.K.; Buiting, K.; Gabriel, J.M.; Saitoh, S.; Muralidhar, B.; Bilienska, B.; Krajewska-Walasek, M.; Driscoll, D.J.; et al. Imprinting-mutation mechanisms in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999, 64, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, S.J. RNAs of the human chromosome 15q11-q13 imprinted region. Wiley Int. Rev. RNA 2013, 4, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocher, M.A.; Huang, F.W.; Le, E.; Good, D.J. Snord116 Post-transcriptionally Increases Nhlh2 mRNA Stability: Implications for Human Prader-Willi Syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wankhade, U.D.; Good, D.J. Melanocortin 4 receptor is a transcriptional target of nescient helix-loop-helix-2. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2011, 341, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landers, M.; Bancescu, D.L.; Le Meur, E.; Rougeulle, C.; Glatt-Deeley, H.; Brannan, C.; Muscatelli, F.; Lalande, M. Regulation of the large (approximately 1000 kb) imprinted murine Ube3a antisense transcript by alternative exons upstream of Snurf/Snrpn. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2004, 32, 3480–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryabin, B.V.; Gubar, L.V.; Seeger, B.; Pfeiffer, J.; Handel, S.; Robeck, T.; Karpova, E.; Rozhdestvensky, T.S.; Brosius, J. Deletion of the MBII-85 snoRNA gene cluster in mice results in postnatal growth retardation. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D.J.; Porter, F.D.; Mahon, K.A.; Parlow, A.F.; Westphal, H.; Kirsch, I.R. Hypogonadism and obesity in mice with a targeted deletion of the Nhlh2 gene. Nat. Genet. 1997, 15, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messeguer, X.; Escudero, R.; Farre, D.; Nunez, O.; Martinez, J.; Alba, M.M. PROMO: Detection of known transcription regulatory elements using species-tailored searches. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, 333–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, G.T. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 2020, 369, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Ying, H.; Liao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. lncRNA SNHG14 promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion of thyroid tumour cells by regulating miR-93-5p. Zygote 2022, 30, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burniat, A.; Jin, L.; Detours, V.; Driessens, N.; Goffard, J.C.; Santoro, M.; Rothstein, J.; Dumont, J.E.; Miot, F.; Corvilain, B. Gene expression in RET/PTC3 and E7 transgenic mouse thyroids: RET/PTC3 but not E7 tumors are partial and transient models of human papillary thyroid cancers. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 5107–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoybye, C.; Tauber, M. Approach to the Patient With Prader-Willi Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, B.; Cui, W.; Zhao, Y. Genetic subtypes and phenotypic characteristics of 110 patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjostrom, A.; Hoybye, C. Twenty Years of GH Treatment in Adults with Prader-Willi Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Xing, J. Long Non-coding RNA Small Nucleolar RNA Host Gene 14, a Promising Biomarker and Therapeutic Target in Malignancy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 746714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, R.L.; Powell, W.T.; Yasui, D.H.; Dileep, G.; Resnick, J.; LaSalle, J.M. Prader-Willi locus Snord116 RNA processing requires an active endogenous allele and neuron-specific splicing by Rbfox3/NeuN. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 4051–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.Y.; Jiang, M.; Zhai, X.; Beaudet, A.L.; Wu, R.C. An unexpected function of the Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting center in maternal imprinting in mice. PLoS One 2012, 7, e34348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honea, R.A.; Holsen, L.M.; Lepping, R.J.; Perea, R.; Butler, M.G.; Brooks, W.M.; Savage, C.R. The neuroanatomy of genetic subtype differences in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012, 159B, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalere, J.; Jauregi, J.; Copet, P.; Laurier, V.; Thuilleaux, D.; Postal, V. Investigation of the relationship between electrodermal and behavioural responses to executive tasks in Prader-Willi syndrome: An event-related experiment. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 85, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, P.; Royo, H.; Marty, V.; Bortolin-Cavaille, M.L.; Cavaille, J. Long nuclear-retained non-coding RNAs and allele-specific higher-order chromatin organization at imprinted snoRNA gene arrays. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.S.; Lyon, C.E.; Fox, A.H.; Leung, A.K.; Lam, Y.W.; Steen, H.; Mann, M.; Lamond, A.I. Directed proteomic analysis of the human nucleolus. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audas, T.E.; Jacob, M.D.; Lee, S. Immobilization of proteins in the nucleolus by ribosomal intergenic spacer noncoding RNA. Mol. Cell 2012, 45, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhail, K.; Gunaratnam, L.; Bonicalzi, M.E.; Lee, S. HIF activation by pH-dependent nucleolar sequestration of VHL. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Hinojo, L.; Casamitjana, L.; Pujol, J.; Martinez-Vilavella, G.; Esteba-Castillo, S.; Gimenez-Palop, O.; Freijo, V.; Deus, J.; Caixas, A. Cerebellar Dysfunction in Adults with Prader Willi Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Watanabe, M.; Suzuki, K.; Suzuki, Y. Cerebellar Volumes Associate with Behavioral Phenotypes in Prader-Willi Syndrome. Cerebellum 2020, 19, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherry, S.T.; Ward, M.H.; Kholodov, M.; Baker, J.; Phan, L.; Smigielski, E.M.; Sirotkin, K. dbSNP: The NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2001, 29, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buniello, A.; MacArthur, J.A.L.; Cerezo, M.; Harris, L.W.; Hayhurst, J.; Malangone, C.; McMahon, A.; Morales, J.; Mountjoy, E.; Sollis, E.; et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2019, 47, D1005–D1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Shorter, T.; Brookes, A.J. GWAS Central: A comprehensive resource for the discovery and comparison of genotype and phenotype data from genome-wide association studies. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2020, 48, D933–D940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boger, C.A.; Gorski, M.; McMahon, G.M.; Xu, H.; Chang, Y.C.; van der Most, P.J.; Navis, G.; Nolte, I.M.; de Borst, M.H.; Zhang, W.; et al. NFAT5 and SLC4A10 Loci Associate with Plasma Osmolality. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 2311–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnema, M.; Boer, H.; Collin, P.; Maaskant, M.A.; van Roozendaal, K.E.; Schrander-Stumpel, C.T.; Curfs, L.M. Psychiatric illness in a cohort of adults with Prader-Willi syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, F.R.; Pathak, G.A.; Lencz, T.; Krystal, J.H.; Gelernter, J.; Polimanti, R. Multivariate genome-wide analysis of education, socioeconomic status and brain phenome. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okbay, A.; Baselmans, B.M.; De Neve, J.E.; Turley, P.; Nivard, M.G.; Fontana, M.A.; Meddens, S.F.; Linner, R.K.; Rietveld, C.A.; Derringer, J.; et al. Genetic variants associated with subjective well-being, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism identified through genome-wide analyses. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tideman, J.W.L.; Parssinen, O.; Haarman, A.E.G.; Khawaja, A.P.; Wedenoja, J.; Williams, K.M.; Biino, G.; Ding, X.; Kahonen, M.; Lehtimaki, T.; et al. Evaluation of Shared Genetic Susceptibility to High and Low Myopia and Hyperopia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021, 139, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohonowych, J.E.; Vrana-Diaz, C.J.; Miller, J.L.; McCandless, S.E.; Strong, T.V. Incidence of strabismus, strabismus surgeries, and other vision conditions in Prader-Willi syndrome: Data from the Global Prader-Willi Syndrome Registry. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021, 21, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, J.; Lacassagne, E.; Eddiry, S.; Franchitto, N.; Salles, J.P.; Tauber, M. What can we learn from PWS and SNORD116 genes about the pathophysiology of addictive disorders? Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ariyanfar, S.; Good, D.J. Analysis of SNHG14: A Long Non-Coding RNA Hosting SNORD116, Whose Loss Contributes to Prader–Willi Syndrome Etiology. Genes 2023, 14, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14010097

Ariyanfar S, Good DJ. Analysis of SNHG14: A Long Non-Coding RNA Hosting SNORD116, Whose Loss Contributes to Prader–Willi Syndrome Etiology. Genes. 2023; 14(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleAriyanfar, Shadi, and Deborah J. Good. 2023. "Analysis of SNHG14: A Long Non-Coding RNA Hosting SNORD116, Whose Loss Contributes to Prader–Willi Syndrome Etiology" Genes 14, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14010097

APA StyleAriyanfar, S., & Good, D. J. (2023). Analysis of SNHG14: A Long Non-Coding RNA Hosting SNORD116, Whose Loss Contributes to Prader–Willi Syndrome Etiology. Genes, 14(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14010097