Identification of Putative SNP Markers Associated with Resistance to Egyptian Loose Smut Race(s) in Spring Barley

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

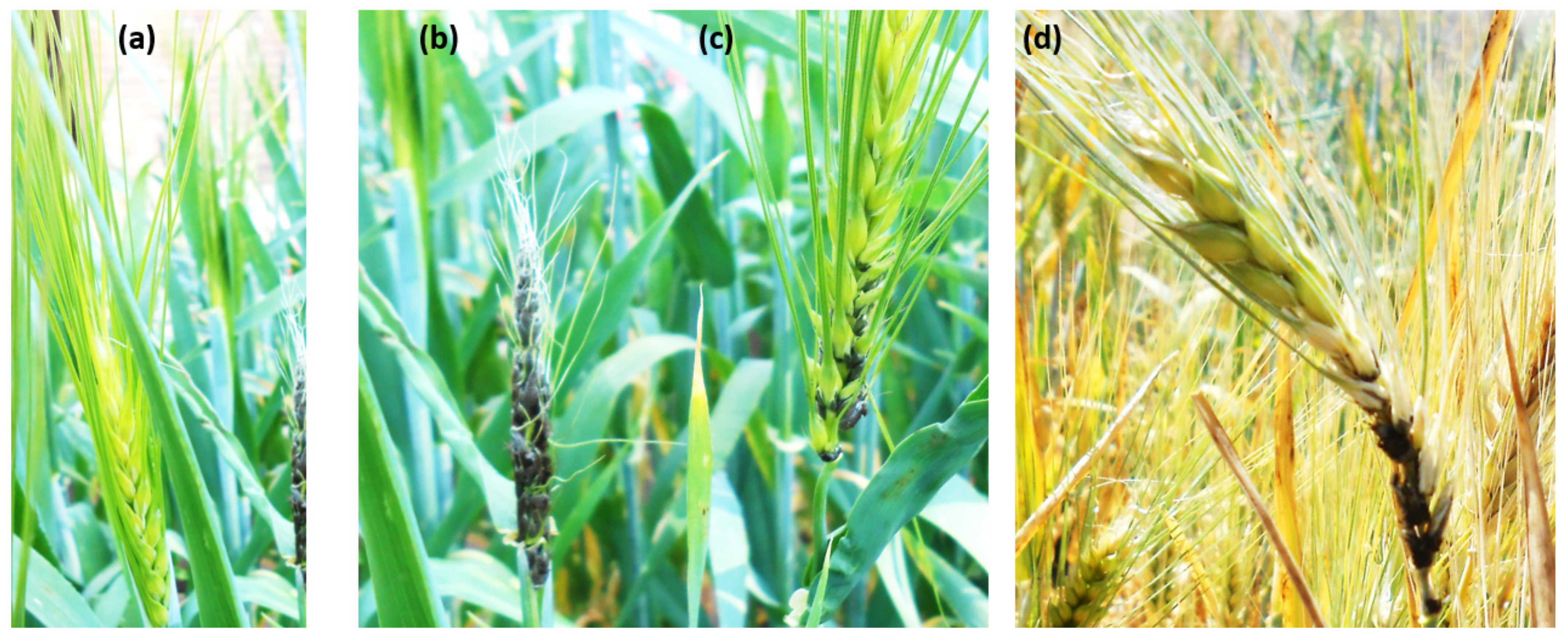

2.2. Evaluation of LS Resistance

2.3. Statistical Analysis of LS Resistance

2.4. DNA Extraction and Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS)

2.5. Single Marker Analysis of LS Resistance and Linkage Disequilibrium

2.6. Gene Models Underlying Significant SNPs and Their Validation

2.7. Screening of the Genotypes for the Presence of the Un8 LS Resistance Gene

3. Results

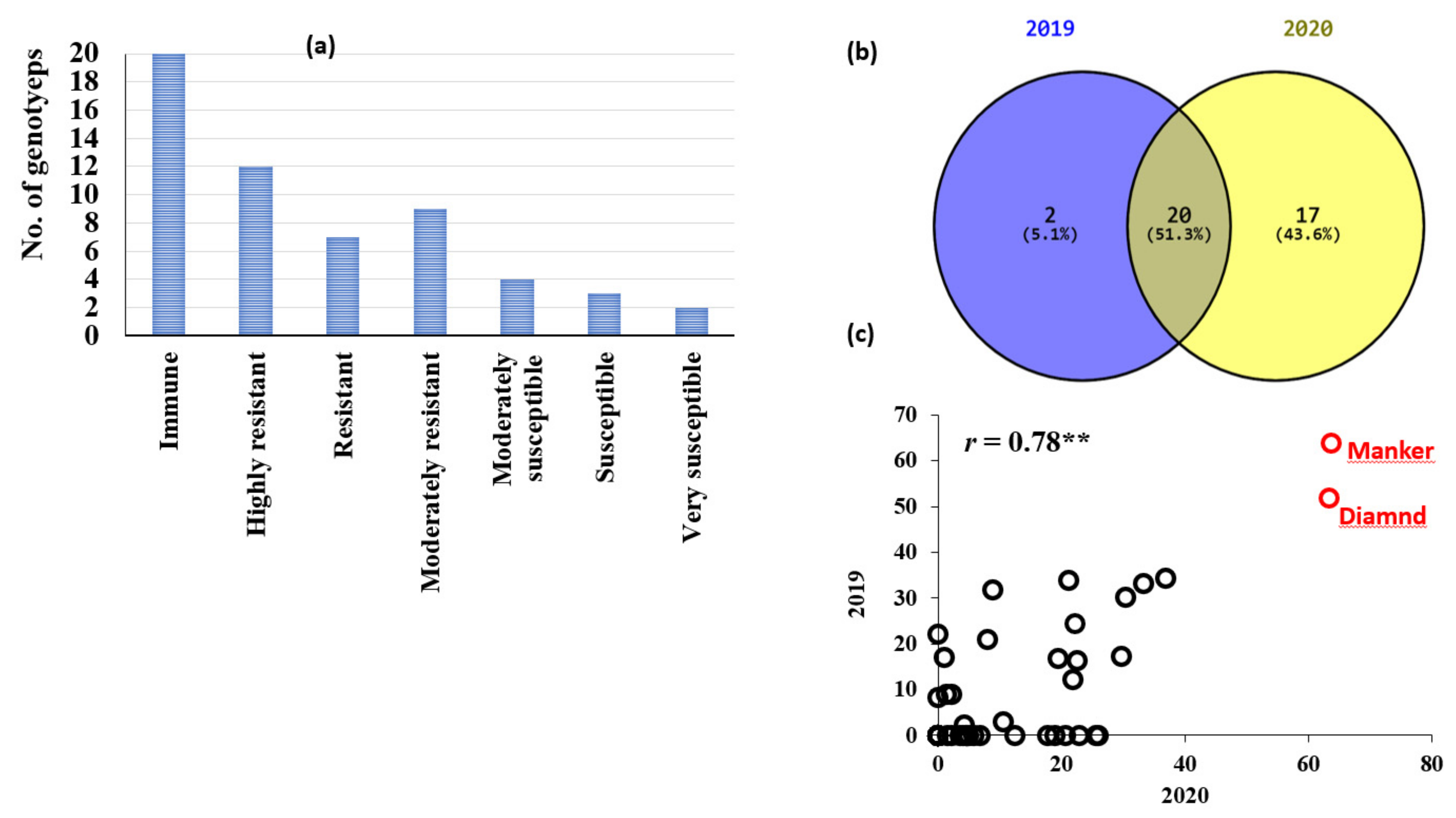

3.1. Phenotypic Variation in Loose Smut Resistance in the Tested Genotypes

3.2. Single-Marker Analysis of Loose Smut Resistance against the Egyptian Race and Linkage Disequilibrium between the Significant SNPs

3.3. Genes Underlying Significant SNPs and Their Validation

3.4. Genotyping with Un-8 Taqman Marker

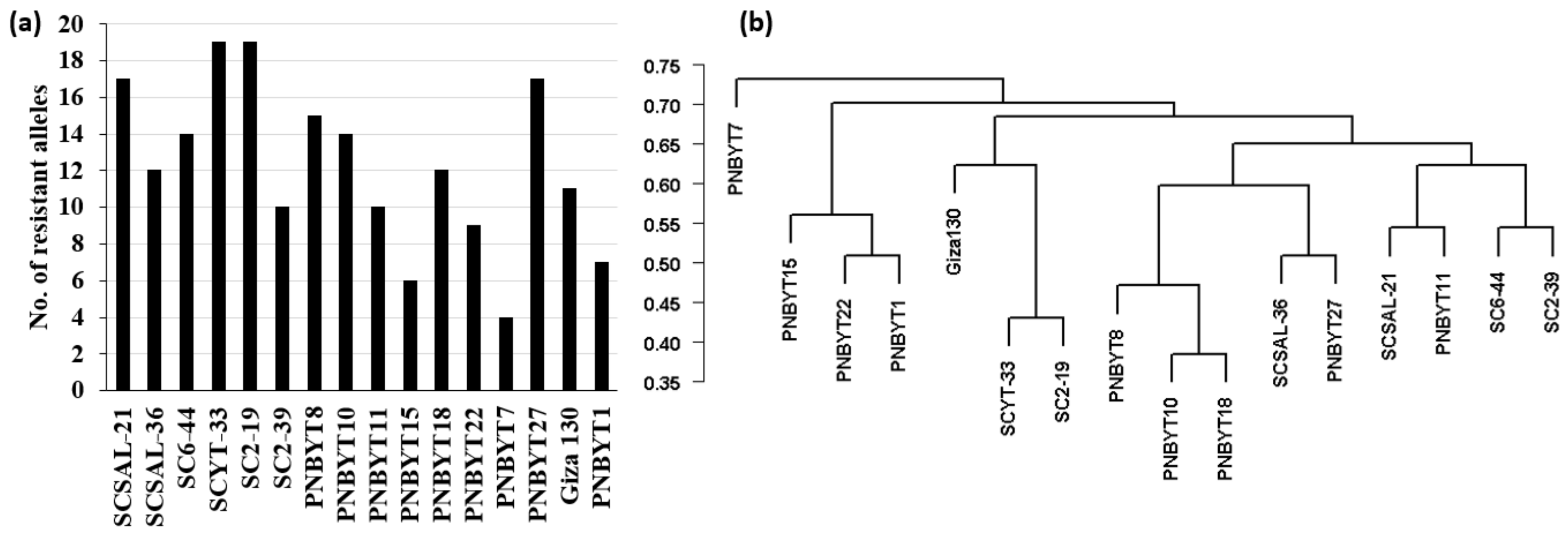

3.5. Selection of Superior Loose Smut Resistance Genotypes

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Variation in Loose Smut Resistance

4.2. Genetic Analysis of LS Resistance

4.3. Genotyping of Un8 LS Resistant Gene

4.4. Selection of Superior Genotypes to LS Resistance

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cappers, R.; Fantone, F.; Neef, R.; van Doorn, C. Archaeobotanical Evidence of the Fungus Covered Smut (Ustilago hordei) in Jordan and Egypt. Analecta Prashist. Leiden. 2012, 44, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Tekauz, A. Diseases of Barley. In Diseases of Field Crops in Canada; University of Saskatchewan: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2003; pp. 30–53. [Google Scholar]

- Menzies, J.G.; Steffenson, B.J.; Kleinhofs, A. A Resistance Gene to Ustilago Nuda in Barley Is Located on Chromosome 3H. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 32, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxson, R.D.; Saari, E.E. Bunt and Smut Diseases of Wheat: Concepts and Methods of Disease Management; Hettel, G., McNab, A., Eds.; CIMMYT: Veracruz, Mexico, 1996; ISBN 9686923373. [Google Scholar]

- Kissoudis, C.; van de Wiel, C.; Visser, R.G.F.; van der Linden, G. Enhancing Crop Resilience to Combined Abiotic and Biotic Stress through the Dissection of Physiological and Molecular Crosstalk. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Livingston, J.E. Inheritance of Resistance to Ustilago Nuda. Phytopathology 1942, 32, 451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, D.W.; Wiebe, G.A.; Shands, R.G. A Summary of Linkage Studies in Barley: Supplement II, 1947–1953. Agron. J. 1947, 47, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, C.W. Inheritance of Resistance to Loose Smut, Ustilago Nuda, in Barley. Phytopathology 1949, 39, 959–979. [Google Scholar]

- Skoropad, W.; Johnson, L. Inheritance of Resistance to Ustilago Nuda in Barley. Can. J. Bot. 1952, 30, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J. Inheritance of Reaction to Loose Smut, Ustilago Nuda, and to Stem Rust, Puccinia Graminis Tritici, in Barley. Can. J. Agicultural Sci. 1956, 36, 356–370. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, D.R. Inheritance of Loose Smut Resistance: III. Relationships between the “Russian” and “Jet” Genes for Resistance and Genes in 10 Barley Varieties of Diverse Origin. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2011, 46, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Chen, B.; Wang, W.; Su, J.; Feng, A.; Zeng, L.; Zhu, X. Identification of the Novel Bacterial Blight Resistance Gene Xa46(t) by Mapping and Expression Analysis of the Rice Mutant H120. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.L.; Menzies, J.G. Cereal Smuts in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, 1989–1995. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 1997, 19, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.-L. Plant Marker-Assisted Breeding and Conventional Breeding: Challenges and Perspectives. Adv. Crop Sci. Technol. 2013, 1, e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, K.F.X.; Martis, M.; Hedley, P.E.; Simková, H.; Liu, H.; Morris, J.A.; Steuernagel, B.; Taudien, S.; Roessner, S.; Gundlach, H.; et al. Unlocking the Barley Genome by Chromosomal and Comparative Genomics. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eckstein, P.E.; Krasichynska, N.; Voth, D.; Duncan, S.; Rossnagel, B.G.; Scoles, G.J. Development of PCR-Based Markers for a Gene (Un8) Conferring True Loose Smut Resistance in Barley. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2002, 24, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, W.; Eckstein, P.E.; Colin, M.; Voth, D.; Himmelbach, A.; Beier, S.; Stein, N.; Scoles, G.J.; Beattie, A.D. Fine Mapping and Identification of a Candidate Gene for the Barley Un8 True Loose Smut Resistance Gene. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, A.; Amro, A.; El-Akhdar, A.; Dawood, M.F.A.; Kumamaru, T.; Baenziger, P.S. Genetic Diversity and Genetic Variation in Morpho-Physiological Traits to Improve Heat Tolerance in Spring Barley. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018, 45, 2441–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Tiwari, S.; Khare, M. Studies on Loose Smut of Wheat. X. Testing of Resistance and Susceptibility of Wheat Varieties to Ustilago tritici (Pers.) Rostr. under Artificial Inoculation. Indian J. Mycol. Plant Pathol. 1990, 20, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyass, M.B.; Ahmad, M.I.; Bajwa, M.A. Evaluation of Inoculation Methods and Screening of Wheat Germplasm against Loose Smut of Wheat. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 1999, 27, 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 4.1.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017.

- Mourad, A.M.I.; Sallam, A.; Belamkar, V.; Wegulo, S.; Bowden, R.; Jin, Y.; Mahdy, E.; Bakheit, B.; El-Wafaa, A.A.; Poland, J.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study for Identification and Validation of Novel SNP Markers for Sr6 Stem Rust Resistance Gene in Bread Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poland, J.A.; Rife, T.W. Genotyping-by-Sequencing for Plant Breeding and Genetics. Plant Genome 2012, 5, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradbury, P.J.; Zhang, Z.; Kroon, D.E.; Casstevens, T.M.; Ramdoss, Y.; Buckler, E.S. TASSEL: Software for Association Mapping of Complex Traits in Diverse Samples. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2633–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Muse, S.V. PowerMarker: An Integrated Analysis Environment for Genetic Marker Analysis. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 2128–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, J.-H.; Blay, S.; McNeney, B.; Graham, J. LDheatmap: An R Function for Graphical Display of Pairwise Linkage Disequilibria between Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. J. Stat. Softw. 2006, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A.B. The Ade4 Package: Implementing the Duality Diagram for Ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhitaphichit, P.; Jones, P.; Keane, E.M. Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Gene Control of Resistance to Loose Smut (Ustilago tritici (Pers.) Rostr.) in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 1989, 78, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, R.; Xiong, H.; Wang, A.; Chen, G. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Hull-Caryopsis Adhesion/Separation Revealed by Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of Covered/Naked Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 14181–14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, J.; Pratap, A.; Solanki, R.K.; Gupta, D.S.; Goyal, A.; Chaturvedi, S.K.; Nadarajan, N.; Kumar, S. Genomic Resources for Improving Food Legume Crops. J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 150, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, A.M.; Sallam, A.; Baenziger, P.S.; Börner, A. GWAS: Fast-Forwarding Gene Identification and Characterization in Temperate Cereals: Lessons from Barley—A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 22, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.H. Statistical Genomics: Linkage, Mapping, and QTL Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998; ISBN 9780367400743. [Google Scholar]

- Moursi, Y.S.; Thabet, S.G.; Amro, A.; Dawood, M.F.A.; Stephen Baenziger, P.; Sallam, A. Detailed Genetic Analysis for Identifying QTLs Associated with Drought Tolerance at Seed Germination and Seedling Stages in Barley. Plants 2020, 9, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.F.A.; Moursi, Y.S.; Amro, A.; Baenziger, P.S.; Sallam, A. Investigation of Heat-Induced Changes in the Grain Yield and Grains Metabolites, with Molecular Insights on the Candidate Genes in Barley. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, A.M.I.; Sallam, A.; Belamkar, V.; Wegulo, S.; Bai, G.; Mahdy, E.; Bakheit, B.; El-Wafa, A.A.; Jin, Y.; Baenziger, P.S. Molecular Marker Dissection of Stem Rust Resistance in Nebraska Bread Wheat Germplasm. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Zeid, M.A.; Mourad, A.M.I. Genomic Regions Associated with Stripe Rust Resistance against the Egyptian Race Revealed by Genome-Wide Association Study. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourad, A.M.I.; Sallam, A.; Belamkar, V.; Mahdy, E.; Bakheit, B.; El-wafaa, A.A.; Baenziger, P.S. Genetic Architecture of Common Bunt Resistance in Winter Wheat Using Genome- Wide Association Study. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffaele, S.; Leger, A.; Roby, D. Very Long Chain Fatty Acid and Lipid Signaling in the Response of Plants to Pathogens. Plant Signal. Behav. 2009, 4, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, L.; Li, G. FAR1-Related Sequence (FRS) and FRS-Related Factor (FRF) Family Proteins in Arabidopsis Growth and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Kong, L.; Zhi, P.; Chang, C. Update on Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis and Its Roles in Plant Disease Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.; Xing, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Qian, C.; Ni, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, D.; et al. Serine/Threonine Kinase Gene Stpk-V, a Key Member of Powdery Mildew Resistance Gene Pm21, Confers Powdery Mildew Resistance in Wheat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7727–7732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brueggeman, R.; Drader, T.; Kleinhofs, A. The Barley Serine/Threonine Kinase Gene Rpg1 Providing Resistance to Stem Rust Belongs to a Gene Family with Five Other Members Encoding Kinase Domains. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 113, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Uauy, C.; Distelfeld, A.; Blechl, A.; Epstein, L.; Chen, X.; Sela, H.; Fahima, T.; Dubcovsky, J. A Kinase-START Gene Confers Temperature-Dependent Resistance to Wheat Stripe Rust. Science 2009, 323, 1357–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kobe, B.; Kemp, B.E. Principles of Kinase Regulation. In Handbook of Cell Signaling; Bradshaw, R., Dennis, E., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 1–3, ISBN 9780080533575. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P.L.; Metcalfe, D.R. Loose Smt Resistance in Two Introduction of Barely from Ethiopia. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1984, 64, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertan, I.; De Carvalho, F.I.F.; Oliveira, A.C. De Parental Selection Strategies in Plant Breeding Programs. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2007, 10, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

| Source | d.f | M.S. |

|---|---|---|

| Years (Y) | 1 | 13.79 |

| Replications (R) | 2 | 216.30 * |

| Genotypes (G) GR | 56 112 | 1231.26 ** 51.91 |

| GY | 56 | 58.33 |

| GYR | 110 | 46.53 |

| Heritability | 0.95 | |

| SNP ID | Chrom. | p-Value | F-Value | R2 | Target Allele | Allele Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1_523594 | 1H | 0.000652344 | 13.86 | 27.256 | G/A | −15.54% |

| S2_6903688 | 2H | 3.37 × 10−5 | 24.62 | 47.70 | C/G | −14.57% |

| S2_6903698 | 0.000697591 | 14.65 | 35.172 | G/C | −15.57% | |

| S2_71163470 | 0.000146541 | 18.71 | 37.643 | C/T | −21.92% | |

| S2_481116363 | 0.000366765 | 16.12 | 34.949 | A/G | −13.15% | |

| S3_4158424 | 3H | 0.000906049 | 8.282851873 | 0.545 | C/T | −1.71% |

| S3_4158440 | 0.00081791 | 8.424957364 | 1.085 | C/T | −3.23% | |

| S3_51209627 | 0.000847857 | 8.374949083 | 17.162 | T/C | −9.57% | |

| S3_346828235 | 0.00072923 | 8.585119232 | 24.637 | C/T | −17.09% | |

| S3_425653844 | 0.000956134 | 8.208412451 | 19.239 | T/C | −9.89% | |

| S3_543138543 | 0.000282644 | 9.941050754 | 14.42 | G/A | −8.31% | |

| S3_546418133 | 0.000758585 | 8.529945709 | 27.916 | T/C | −17.86% | |

| S3_546728405 | 1.85 × 10−5 | 14.18761801 | 26.1 | G/A | −19.87% | |

| S3_546728420 | 0.000332253 | 9.705460245 | 27.021 | A/G | −13.42% | |

| S3_546788379 | 0.000127966 | 11.12149677 | 33.878 | T/A | −23.57% | |

| S3_546788391 | 0.000127966 | 11.12149677 | 33.878 | A/G | −23.57% | |

| S3_546788395 | 0.000127966 | 11.12149677 | 33.878 | C/A | −23.57% | |

| S3_557269134 | 0.000761867 | 8.523916211 | 24.861 | T/A | −10.69% | |

| S4_510236504 | 4H | 0.000617005 | 8.819871045 | 16.644 | A/G | −8.94% |

| S4_510236509 | 0.000617005 | 8.819871045 | 16.644 | A/G | −8.94% | |

| S5_8264909 | 5H | 0.000755518 | 8.53560527 | 22.878 | A/G | −10.61% |

| S6_17854595 | 6H | 0.000986781 | 8.164849355 | 5.432 | A/G | −7.81% |

| S7_10286228 | 7H | 0.000558655 | 8.960296029 | 7.383 | G/A | −8.22% |

| S7_27627925 | 0.000429506 | 9.335043364 | 0.776 | T/C | −2.17% | |

| S7_50465300 | 0.000980333 | 8.173896443 | 3.264 | A/G | −3.92% | |

| S7_50465325 | 0.000980333 | 8.173896443 | 3.264 | A/G | −3.92% | |

| S7_54495415 | 0.000855639 | 8.36225696 | 7.226 | C/G | −7.61% |

| SNP ID | Chrom. | Gene Model | Gene Model Position (bp) | Pos. (Gene Model) | GD (Gene Model) | Gene Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1_523594 | 1H | HORVU1Hr1G000190 | 514755-520291 | after | 3033 | Fatty acyl-CoA reductase |

| S2_6903688 | 2H | NA | NA | NA | ||

| S2_6903698 | ||||||

| S2_71163470 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| S2_481116363 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| S3_4158424 | 3H | HORVU3Hr1G002060 | 4158879-4162702 | before | 455 | O-acyltransferase (WSD1-like) family |

| S3_4158440 | HORVU3Hr1G002060 | 4158879-4162702 | before | 439 | O-acyltransferase (WSD1-like) family protein | |

| S3_51209627 | HORVU3Hr1G019140 | 51126683-51134627 | after | 75000 | receptor kinase 1 | |

| S3_346828235 | HORVU3Hr1G049410 | 346862885-346863988 | before | 34650 | Disease resistance protein RPM1 | |

| S3_425653844 | HORVU3Hr1G056930 | 425800602-425801141 | before | 146758 | Protein H | |

| S3_543138543 | HORVU3Hr1G071870 | 543136922-543138097 | Uncharacterized protein | |||

| S3_546418133 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| S3_546728405 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| S3_546728420 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| S3_546788379 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| S3_546788391 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| S3_546788395 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| S3_557269134 | HORVU3Hr1G074130 | 557216044-557217268 | after | 51866 | Holliday junction DNA helicase | |

| S4_510236504 | 4H | HORVU4Hr1G060790 | 510209263-510210332 | after | 26172 | unknown function |

| S4_510236509 | HORVU4Hr1G013970 | 510209263-510210332 | after | 27246 | unknown function | |

| S5_8264909 | 5H | NA | NA | NA | ||

| S6_17854595 | 6H | HORVU6Hr1G010050 | 17851141-17927010 | within | - | Protein kinase domain-containing protein |

| S7_10286228 | 7H | HORVU7Hr1G007880 | 10273667-10273950 | after | 12278 | HAT family dimerisation domain containing protein, expressed |

| S7_27627925 | HORVU7Hr1G020360 | 27617705-27618557 | after | 9368 | undescribed protein | |

| S7_50465300 | HORVU7Hr1G028130 | 50500827-50501771 | before | 35527 | NA | |

| S7_50465325 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| S7_54495415 | HORVU7Hr1G029150 | 54451633-54453868 | after | 41547 | Ubiquitin-like domain-containing protein |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abo-Elyousr, K.A.M.; Mourad, A.M.I.; Baenziger, P.S.; Shehata, A.H.A.; Eckstein, P.E.; Beattie, A.D.; Sallam, A. Identification of Putative SNP Markers Associated with Resistance to Egyptian Loose Smut Race(s) in Spring Barley. Genes 2022, 13, 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13061075

Abo-Elyousr KAM, Mourad AMI, Baenziger PS, Shehata AHA, Eckstein PE, Beattie AD, Sallam A. Identification of Putative SNP Markers Associated with Resistance to Egyptian Loose Smut Race(s) in Spring Barley. Genes. 2022; 13(6):1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13061075

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbo-Elyousr, Kamal A. M., Amira M. I. Mourad, P. Stephen Baenziger, Abdelaal H. A. Shehata, Peter E. Eckstein, Aaron D. Beattie, and Ahmed Sallam. 2022. "Identification of Putative SNP Markers Associated with Resistance to Egyptian Loose Smut Race(s) in Spring Barley" Genes 13, no. 6: 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13061075

APA StyleAbo-Elyousr, K. A. M., Mourad, A. M. I., Baenziger, P. S., Shehata, A. H. A., Eckstein, P. E., Beattie, A. D., & Sallam, A. (2022). Identification of Putative SNP Markers Associated with Resistance to Egyptian Loose Smut Race(s) in Spring Barley. Genes, 13(6), 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13061075