Nitrate Modulates Lateral Root Formation by Regulating the Auxin Response and Transport in Rice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

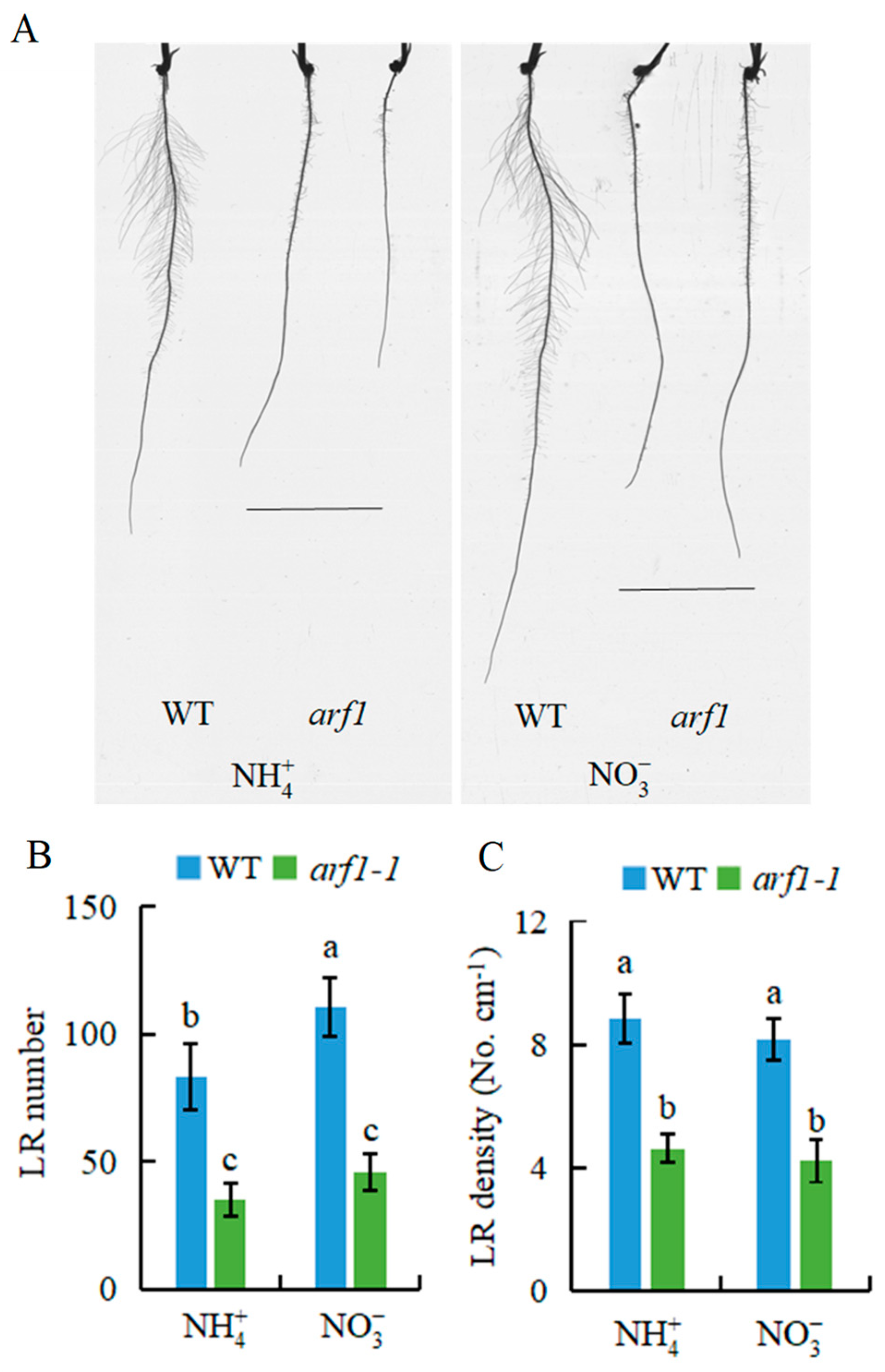

2.1. Nitrate Regulated LR Formation in Rice

2.2. Auxin Is Involved in -Modulated LR Formation

2.3. SLs Are Also Involved in -Modulated LR Formation

2.4. OsPIN2 Is Involved in -Modulated Auxin Levels and LR Formation in Rice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Plant Growth

4.3. Root System Architecture

4.4. Determination of IAA Content

4.5. qRT-PCR Analysis

4.6. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patterson, K.; Walters, L.A.; Cooper, A.M.; Olvera, J.G.; Rosas, M.A.; Rasmusson, A.G.; Escobar, M.A. Nitrate-regulated glutaredoxins control Arabidopsis primary root growth. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, Z.; Amtmann, A. Food for thought: How nutrients regulate root system architecture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Feng, F.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Q. Nitric oxide affect rice root growth by regulating auxin transport under nitrate supply. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liang, Z.; Chen, S.; Sun, H.; Fan, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Y. A transcription factor, OsMADS57, regulates long-distance nitrate transport and root elongation. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Fan, X.; Chen, J.; Qu, H.; Luo, L.; Xu, G. OsNAR2.1 interaction with OsNIT1 and OsNIT2 functions in root-growth responses to nitrate and ammonium. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Z.; Luo, L.; Zhang, C.; Pélissier, P.; Parizot, B.; Qi, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; et al. Rice plants respond to ammonium-stress by adopting a helical root growth pattern. Plant J. 2020, 104, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Guo, X.; Qi, X.; Feng, F.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q. SPL14/17 act downstream of strigolactone signalling to modulate root elongation in response to nitrate supply in rice. Plant J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, B.D.; Giehl, R.F.H.; Friedel, S.; Von Wirén, N. Plasticity of the Arabidopsis root system under nutrient deficiencies. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; De Smet, I.; Ding, Z. Shaping a root system: Regulating lateral versus primary root growth. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Smet, I.; Vanneste, S.; Inzé, D.; Beeckman, T. Lateral root initiation or the birth of a new meristem. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 60, 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Forde, B. An Arabidopsis MADS box gene that controls nutrient-induced changes in root architecture. Science 1998, 279, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Crawford, N. Arabidopsis nitric oxide synthase1 is targeted to mitochondria and protects against oxidative damage and dark-induced senescence. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 3436–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; Gong, X.; Huang, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, G. Auxin distribution is differentially affected by nitrate in roots of two rice cultivars differing in responsiveness to nitrogen. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, S.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yan, M.; Chen, J.; Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y. Knockdown of the partner protein OsNAR2.1 for high-affinity nitrate transport represses lateral root formation in a nitrate-dependent manner. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Mo, Q.; Zou, C.; Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Xie, C. Combined small RNA and degradome sequencing reveals novel miRNAs and their targets in response to low nitrate availability in maize. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.; Riveras, E.; Vidal, E.; Gras, D.; Contreras-López, O.; Tamayo, K.; Aceituno, F.; Gómez, I.; Ruffel, S.; Lejay, L.; et al. Systems approach identifies TGA1 and TGA4 transcription factors as important regulatory components of the nitrate response of Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Plant J. 2014, 80, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, H.; Hamera, S.; Chen, X.; Fang, R. miR444a has multiple functions in rice nitrate-signaling pathway. Plant J. 2014, 78, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Su, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, A.; Huang, L.; Ali, I.; Gan, Y. The effects of fluctuations in the nutrient supply on the expression of five members of the AGL17 clade of MADS-box genes in rice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Zheng, Y.; Feng, H.; Qu, H.; Fan, X.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J.F.; Xu, G. OsNRT2.4 encodes a dual-affinity nitrate transporter and functions in nitrate-regulated root growth and nitrate distribution in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Li, J.; Qu, B.; He, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, B.; Fu, X.; Tong, Y. Auxin biosynthetic gene TAR2 is involved in low nitrogen-mediated reprogramming of root architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2014, 78, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Jennings, A.; Barlow, P.W.; Forde, B.G. Dual pathways for regulation of root branching by nitrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 6529–6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krouk, G.; Lacombe, B.; Bielach, A.; Perrine-Walker, F.; Malinska, K.; Mounier, E.; Hoyerova, K.; Tillard, P.; Leon, S.; Ljung, K.; et al. Nitrate-regulated auxin transport by NRT1.1 defines a mechanism for nutrient sensing in plants. Dev. Cell. 2010, 18, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remans, T.; Nacry, P.; Pervent, M.; Filleur, S.; Diatloff, E.; Mounier, E.; Tillard, P.; Forde, B.G.; Gojon, A. The Arabidopsis NRT1.1 transporter participates in the signaling pathway triggering root colonization of nitrate-rich patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19206–19211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounier, E.; Pervent, M.; Ljung, K.; Gojon, A.; Nacry, P. Auxin-mediated nitrate signalling by NRT1.1 participates in the adaptive response of Arabidopsis root architecture to the spatial heterogeneity of nitrate availability. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; An, X.; Cheng, L.; Chen, F.; Bao, J.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, F.; Mi, G. Auxin transport in maize roots in response to localized nitrate supply. Ann. Bot. 2010, 106, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Q.; Chen, F.; Liu, J.; Zhang, F.; Mi, G. Inhibition of maize root growth by high nitrate supply is correlated with reduced IAA levels in roots. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruyter-Spira, C.; Kohlen, W.; Charnikhova, T.; van Zeijl, A.; van Bezouwen, L.; de Ruijter, N.; Cardoso, C.; Lopez-Raez, J.A.; Matusova, R.; Bours, R.; et al. Physiological effects of the synthetic strigolactone analog GR24 on root system architecture in Arabidopsis: Another belowground role for strigolactones? Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapulnik, Y.; Delaux, P.-M.; Resnick, N.; Mayzlish-Gati, E.; Wininger, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Séjalon-Delmas, N.; Combier, J.-P.; Bécard, G.; Belausov, E.; et al. Strigolactones affect lateral root formation and root-hair elongation in Arabidopsis. Planta 2011, 233, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayzlish-Gati, E.; De-Cuyper, C.; Goormachtig, S.; Beeckman, T.; Vuylsteke, M.; Brewer, P.B.; Beveridge, C.A.; Yermiyahu, U.; Kaplan, Y.; Enzer, Y.; et al. Strigolactones are involved in root response to low phosphate conditions in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1329–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Tao, J.; Liu, S.; Huang, S.; Chen, S.; Xie, X.; Yoneyama, K.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, G. Strigolactones are involved in phosphate and nitrate deficiency-induced root development and auxin transport in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 6735–6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Siddeqi, M.; Ruth, T.; Glass, A. Ammonium uptake by rice roots. I. Kinetics of 13NH4+ influx across the plasmalemma. Plant Physiol. 1993, 103, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronzucker, H.J.; Glass, A.D.M.; Siddiqi, M.Y.; Kirk, G.J.D. Comparative kinetic analysis of ammonium and nitrate acquisition by tropical lowland rice: Implications for rice cultivation and yield potential. New Phytol. 2000, 145, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, G.J.; Kronzucker, H.J. The potential for nitrification and nitrate uptake in the rhizosphere of wetland plants: A modelling study. Ann. Bot. 2005, 96, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.P.; Vitousek, P.M. Nitrogen in agriculture: Balancing the cost of an essential resource. Ann. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J. Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Beeckman, T.; Xu, G. Plant nitrogen nutrition: Sensing and signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojon, A.; Krouk, G.; Perrine-Walker, F.; Laugier, E. Nitrate transceptor(s) in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2299–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Pandya-Kumar, N.; Dam, A.; Haor, H.; Mayzlish-Gati, E.; Belausov, E.; Wininger, S.; Abu-Abied, M.; McErlean, C.S.P.; Bromhead, L.J.; et al. Arabidopsis response to low-phosphate conditions includes active changes in actin filaments and PIN2 polarization and is dependent on strigolactones signaling. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Bi, Y.; Tao, J.; Huang, S.; Hou, M.; Xue, R.; Liang, Z.; Gu, P.; Yoneyama, K.; Xie, X.; et al. Strigolactones are required for nitric oxide to induce root elongation in response to nitrogen and phosphate deficiencies in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Dong, C. Effects of different nitrogen forms on the growth and cytokinin content in xylem sap of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) seedlings. Plant Soil 2009, 315, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmasov, T.; Murfett, J.; Hagen, G.; Guilfoyle, T.J. Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1963–1971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Ren, H.; Gu, M.; Zhao, J.; Sun, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, P.; Xu, G. The phosphate transporter gene OsPht1;8 is involved in phosphate homeostasis in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1164–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Zhu, X.; Guo, X.; Qi, X.; Feng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Han, D.; Sun, H. Nitrate Modulates Lateral Root Formation by Regulating the Auxin Response and Transport in Rice. Genes 2021, 12, 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12060850

Wang B, Zhu X, Guo X, Qi X, Feng F, Zhang Y, Zhao Q, Han D, Sun H. Nitrate Modulates Lateral Root Formation by Regulating the Auxin Response and Transport in Rice. Genes. 2021; 12(6):850. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12060850

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bobo, Xiuli Zhu, Xiaoli Guo, Xuejiao Qi, Fan Feng, Yali Zhang, Quanzhi Zhao, Dan Han, and Huwei Sun. 2021. "Nitrate Modulates Lateral Root Formation by Regulating the Auxin Response and Transport in Rice" Genes 12, no. 6: 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12060850

APA StyleWang, B., Zhu, X., Guo, X., Qi, X., Feng, F., Zhang, Y., Zhao, Q., Han, D., & Sun, H. (2021). Nitrate Modulates Lateral Root Formation by Regulating the Auxin Response and Transport in Rice. Genes, 12(6), 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12060850