Network Protein Interaction in the Link between Stroke and Periodontitis Interplay: A Pilot Bioinformatic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Protein–Protein Interaction Networks Functional Enrichment Analysis

2.3. Data Management, Test Methods and Analysis

2.4. Gene Enrichment Analysis

3. Results

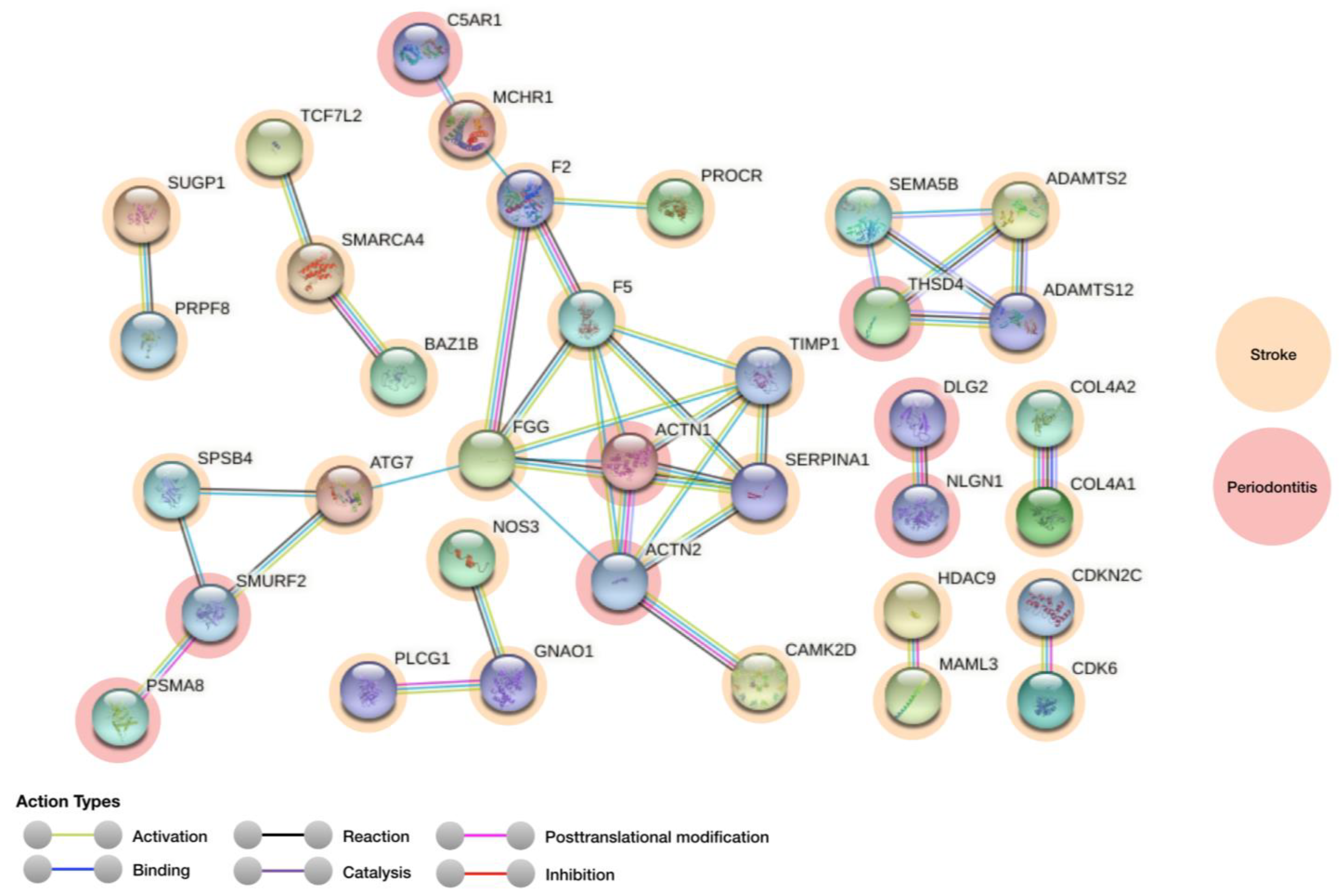

3.1. Protein–Protein Interaction Analysis

3.2. Gene Enrichment Assessment and Gene Ontology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Nichols, E.; Alam, T.; Bannick, M.S.; Beghi, E.; Blake, N.; Culpepper, W.J.; Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Neurological Disorders, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 Lifetime Risk of Stroke Collaborators. Global, Regional, and Country-Specific Lifetime Risks of Stroke, 1990 and 2016. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2429–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.C.V.; Khatri, P. Stroke. Lancet 2020, 396, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo-Fernandez, R.; Violato, M.; Candio, P.; Leal, J. Economic Burden of Stroke across Europe: A Population-Based Cost Analysis. Eur. Stroke J. 2020, 5, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinane, D.F.; Stathopoulou, P.G.; Papapanou, P.N. Periodontal Diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2017, 3, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Bernabé, E.; Dahiya, M.; Bhandari, B.; Murray, C.J.L.; Marcenes, W. Global Burden of Severe Periodontitis in 1990–2010. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkein, H.A.; Loos, B.G. Inflammatory Mechanisms Linking Periodontal Diseases to Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leira, Y.; Seoane, J.; Blanco, M.; Rodríguez-Yáñez, M.; Takkouche, B.; Blanco, J.; Castillo, J. Association between Periodontitis and Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 32, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leira, Y.; Rodríguez-Yáñez, M.; Arias, S.; López-Dequidt, I.; Campos, F.; Sobrino, T.; D’Aiuto, F.; Castillo, J.; Blanco, J. Periodontitis as a Risk Indicator and Predictor of Poor Outcome for Lacunar Infarct. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Sumner, R.; Hardin, J.; Barros, S.; Moss, K.; Beck, J.; Offenbacher, S. Periodontal Disease and Recurrent Vascular Events in Stroke/Transient Ischemic Attack Patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013, 22, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leira Feijóo, Y.; Blanco González, M.; Blanco Carrión, J.; Castillo Sánchez, J. Asociación Entre La Enfermedad Periodontal y La Enfermedad Cerebrovascular. Revisión de La Bibliografía. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 61, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Gibson, J.T.; Harshfield, E.L.; Markus, H.S. Is Periodontitis a Risk Factor for Ischaemic Stroke, Coronary Artery Disease and Subclinical Atherosclerosis? A Mendelian Randomization Study. Atherosclerosis 2020, 313, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.-K.; Bang, O.; Cha, M.-H.; Kim, J.; Cole, J.W.; Lee, D.; Kim, Y. SigCS Base: An Integrated Genetic Information Resource for Human Cerebral Stroke. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011, 5, S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- NHGRI-GWAS The National Human Genome Research Institute-European Bioinformatics Institute Catalog of Human Genome-Wide Association Studies. Available online: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Schaefer, A.S.; Richter, G.M.; Nothnagel, M.; Manke, T.; Dommisch, H.; Jacobs, G.; Arlt, A.; Rosenstiel, P.; Noack, B.; Groessner-Schreiber, B.; et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies GLT6D1 as a Susceptibility Locus for Periodontitis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 19, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divaris, K.; Monda, K.L.; North, K.E.; Olshan, A.F.; Lange, E.M.; Moss, K.; Barros, S.P.; Beck, J.D.; Offenbacher, S. Genome-Wide Association Study of Periodontal Pathogen Colonization. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, S21–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divaris, K.; Monda, K.L.; North, K.E.; Olshan, A.F.; Reynolds, L.M.; Hsueh, W.C.; Lange, E.M.; Moss, K.; Barros, S.P.; Weyant, R.J.; et al. Exploring the Genetic Basis of Chronic Periodontitis: A Genome-Wide Association Study. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 2312–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teumer, A.; Holtfreter, B.; Völker, U.; Petersmann, A.; Nauck, M.; Biffar, R.; Völzke, H.; Kroemer, H.K.; Meisel, P.; Homuth, G.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Chronic Periodontitis in a General German Population. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Wang, X.; Casado, P.L.; Küchler, E.C.; Deeley, K.; Noel, J.; Kimm, H.; Kim, J.H.; Haas, A.N.; Quinelato, V.; et al. Genome Wide Association Scan for Chronic Periodontitis Implicates Novel Locus. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Freitag-Wolf, S.; Dommisch, H.; Graetz, C.; Jockel-Schneider, Y.; Harks, I.; Staufenbiel, I.; Meyle, J.; Eickholz, P.; Noack, B.; Bruckmann, C.; et al. Genome-Wide Exploration Identifies Sex-Specific Genetic Effects of Alleles Upstream NPY to Increase the Risk of Severe Periodontitis in Men. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag-Wolf, S.; Munz, M.; Wiehe, R.; Junge, O.; Graetz, C.; Jockel-Schneider, Y.; Staufenbiel, I.; Bruckmann, C.; Lieb, W.; Franke, A.; et al. Smoking Modifies the Genetic Risk for Early-Onset Periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, J.R.; Polk, D.E.; Wang, X.; Feingold, E.; Weeks, D.E.; Lee, M.K.; Cuenco, K.T.; Weyant, R.J.; Crout, R.J.; McNeil, D.W.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Periodontal Health Measured by Probing Depth in Adults Ages 18–49 Years. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2014, 4, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shungin, D.; Haworth, S.; Divaris, K.; Agler, C.S.; Kamatani, Y.; Keun Lee, M.; Grinde, K.; Hindy, G.; Alaraudanjoki, V.; Pesonen, P.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Dental Caries and Periodontitis Combining Clinical and Self-Reported Data. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, S.; Momozawa, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Nagasawa, T.; Ashikawa, K.; Terada, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Tsuji, M.; Kubo, M.; et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study of Periodontitis in a Japanese Population. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munz, M.; Willenborg, C.; Richter, G.M.; Jockel-Schneider, Y.; Graetz, C.; Staufenbiel, I.; Wellmann, J.; Berger, K.; Krone, B.; Hoffmann, P.; et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Nucleotide Variants at SIGLEC5 and DEFA1A3 as Risk Loci for Periodontitis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 2577–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, L.; Navarra, C.O.; Pirastu, N.; Lenarda, R.D.; Gasparini, P.; Robino, A. A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies an Association between Variants in EFCAB4B Gene and Periodontal Disease in an Italian Isolated Population. J. Periodontal Res. 2018, 53, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munz, M.; Richter, G.M.; Loos, B.G.; Jepsen, S.; Divaris, K.; Offenbacher, S.; Teumer, A.; Holtfreter, B.; Kocher, T.; Bruckmann, C.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies of Aggressive and Chronic Periodontitis Identifies Two Novel Risk Loci. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 27, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, J.; Mascarenhas, P.; Mendes, J.J.; Machado, V. Network Protein Interaction in Parkinson’s Disease and Periodontitis Interplay: A Preliminary Bioinformatic Analysis. Genes 2020, 11, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHGRI-GWAS GWAS Periodontitis Results. Available online: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/efotraits/EFO_0000649 (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Von Berg, J.; van der Laan, S.W.; McArdle, P.F.; Malik, R.; Kittner, S.J.; Mitchell, B.D.; Worrall, B.B.; de Ridder, J.; Pulit, S.L. Alternate Approach to Stroke Phenotyping Identifies a Genetic Risk Locus for Small Vessel Stroke. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochet, H.; Pirinen, M.; Band, G.; Jostins, L.; McVean, G.; Spencer, C.C.A. Bayesian Meta-Analysis across Genome-Wide Association Studies of Diverse Phenotypes. Genet. Epidemiol. 2019, 43, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-H.; Ko, T.-M.; Chen, C.-H.; Chang, Y.-J.; Lu, L.-S.; Chang, C.-H.; Huang, K.-L.; Chang, T.-Y.; Lee, J.-D.; Chang, K.-C.; et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study Links Small-Vessel Ischemic Stroke to Autophagy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderholm, M.; Pedersen, A.; Lorentzen, E.; Stanne, T.M.; Bevan, S.; Olsson, M.; Cole, J.W.; Fernandez-Cadenas, I.; Hankey, G.J.; Jimenez-Conde, J.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis of Functional Outcome after Ischemic Stroke. Neurology 2019, 92, e1271–e1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, R.; Dau, T.; Gonik, M.; Sivakumar, A.; Deredge, D.J.; Edeleva, E.V.; Götzfried, J.; van der Laan, S.W.; Pasterkamp, G.; Beaufort, N.; et al. Common Coding Variant in SERPINA1 Increases the Risk for Large Artery Stroke. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 3613–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traylor, M.; Malik, R.; Nalls, M.A.; Cotlarciuc, I.; Radmanesh, F.; Thorleifsson, G.; Hanscombe, K.B.; Langefeld, C.; Saleheen, D.; Rost, N.S.; et al. Genetic Variation at 16q24.2 Is Associated with Small Vessel Stroke. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschia, J.F.; Singleton, A.; Nalls, M.A.; Rich, S.S.; Sharma, P.; Ferrucci, L.; Matarin, M.; Hernandez, D.G.; Pearce, K.; Brott, T.G.; et al. Genomic Risk Profiling of Ischemic Stroke: Results of an International Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meschia, J.F.; Nalls, M.; Matarin, M.; Brott, T.G.; Brown, R.D.; Hardy, J.; Kissela, B.; Rich, S.S.; Singleton, A.; Hernandez, D.; et al. Siblings With Ischemic Stroke Study. Stroke 2011, 42, 2726–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, M.-Y.; Bang, O.-S.; Cha, M.-H.; Park, Y.-K.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, Y.J. Association of the Adiponectin Gene Variations with Risk of Ischemic Stroke in a Korean Population. Yonsei Med. J. 2011, 52, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Fuku, N.; Tanaka, M.; Aoyagi, Y.; Sawabe, M.; Metoki, N.; Yoshida, H.; Satoh, K.; Kato, K.; Watanabe, S.; et al. Identification of CELSR1 as a Susceptibility Gene for Ischemic Stroke in Japanese Individuals by a Genome-Wide Association Study. Atherosclerosis 2009, 207, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arning, A.; Hiersche, M.; Witten, A.; Kurlemann, G.; Kurnik, K.; Manner, D.; Stoll, M.; Nowak-Göttl, U. A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Gene Network of ADAMTS Genes in the Predisposition to Pediatric Stroke. Blood 2012, 120, 5231–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulminski, A.M.; Huang, J.; Loika, Y.; Arbeev, K.G.; Bagley, O.; Yashkin, A.; Duan, M.; Culminskaya, I. Strong Impact of Natural-Selection–Free Heterogeneity in Genetics of Age-Related Phenotypes. Aging 2018, 10, 492–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-C.; O’Connell, J.R.; Cole, J.W.; Stine, O.C.; Dueker, N.; McArdle, P.F.; Sparks, M.J.; Shen, J.; Laurie, C.C.; Nelson, S.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Ischemic Stroke in Young Adults. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2011, 1, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gretarsdottir, S.; Thorleifsson, G.; Manolescu, A.; Styrkarsdottir, U.; Helgadottir, A.; Gschwendtner, A.; Kostulas, K.; Kuhlenbäumer, G.; Bevan, S.; Jonsdottir, T.; et al. Risk Variants for Atrial Fibrillation on Chromosome 4q25 Associate with Ischemic Stroke. Ann. Neurol. 2008, 64, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarín, M.; Brown, W.M.; Scholz, S.; Simón-Sánchez, J.; Fung, H.-C.; Hernandez, D.; Gibbs, J.R.; De Vrieze, F.W.; Crews, C.; Britton, A.; et al. A Genome-Wide Genotyping Study in Patients with Ischaemic Stroke: Initial Analysis and Data Release. Lancet Neurol. 2007, 6, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, F.; Brickell, A.; Sun, N.; Mao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, B.; Li, F.; et al. Additional Common Loci Associated with Stroke and Obesity Identified Using Pleiotropic Analytical Approach. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2020, 295, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keene, K.L.; Chen, W.-M.; Chen, F.; Williams, S.R.; Elkhatib, S.D.; Hsu, F.-C.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Doheny, K.F.; Pugh, E.W.; Ling, H.; et al. Genetic Associations with Plasma B12, B6, and Folate Levels in an Ischemic Stroke Population from the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) Trial. Front. Public Health 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, R.; Rannikmäe, K.; Traylor, M.; Georgakis, M.K.; Sargurupremraj, M.; Markus, H.S.; Hopewell, J.C.; Debette, S.; Sudlow, C.L.M.; Dichgans, M. Genome-wide Meta-analysis Identifies 3 Novel Loci Associated with Stroke. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 84, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.S.; Bergmeijer, T.O.; Gong, L.; Reny, J.; Lewis, J.P.; Mitchell, B.D.; Alexopoulos, D.; Aradi, D.; Altman, R.B.; Bliden, K.; et al. Genomewide Association Study of Platelet Reactivity and Cardiovascular Response in Patients Treated With Clopidogrel: A Study by the International Clopidogrel Pharmacogenomics Consortium. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 108, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, E.G.; Maguire, J.M.; Evans, T.-J.; Koblar, S.A.; Jannes, J.; Sturm, J.W.; Hankey, G.J.; Baker, R.; Golledge, J.; Parsons, M.W.; et al. Common Variants at 6p21.1 Are Associated with Large Artery Atherosclerotic Stroke. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1147–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.A.; Seshadri, S.; Bis, J.C.; Fornage, M.; DeStefano, A.L.; Aulchenko, Y.S.; Debette, S.; Lumley, T.; Folsom, A.R.; van den Herik, E.G.; et al. Genomewide Association Studies of Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1718–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, C.L.; Keene, K.L.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Meschia, J.F.; Chen, W.-M.; Nalls, M.; Bis, J.C.; Kittner, S.J.; Rich, S.S.; Tajuddin, S.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies Identifies Genetic Risk Factors for Stroke in African Americans. Stroke 2015, 46, 2063–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Lin, Y.; Shen, S.; Liu, C.-L.; Hobbs, B.D.; Hasegawa, K.; Liang, L.; Boezen, H.M.; et al. Genetic Overlap of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Cardiovascular Disease-Related Traits: A Large-Scale Genome-Wide Cross-Trait Analysis. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellenguez, C.; Bevan, S.; Gschwendtner, A.; Spencer, C.C.A.; Burgess, A.I.; Pirinen, M.; Jackson, C.A.; Traylor, M.; Strange, A.; Su, Z.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Variant in HDAC9 Associated with Large Vessel Ischemic Stroke. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traylor, M.; Farrall, M.; Holliday, E.G.; Sudlow, C.; Hopewell, J.C.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Fornage, M.; Ikram, M.A.; Malik, R.; Bevan, S.; et al. Genetic Risk Factors for Ischaemic Stroke and Its Subtypes (the METASTROKE Collaboration): A Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Kernogitski, Y.; Kulminskaya, I.; Loika, Y.; Arbeev, K.G.; Loiko, E.; Bagley, O.; Duan, M.; Yashkin, A.; Ukraintseva, S.V.; et al. Pleiotropic Meta-Analyses of Longitudinal Studies Discover Novel Genetic Variants Associated with Age-Related Diseases. Front. Genet. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, G.; Arnold, C.R.; Chu, A.Y.; Fornage, M.; Reyahi, A.; Bis, J.C.; Havulinna, A.S.; Sargurupremraj, M.; Smith, A.V.; Adams, H.H.H.; et al. Identification of Additional Risk Loci for Stroke and Small Vessel Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulit, S.L.; McArdle, P.F.; Wong, Q.; Malik, R.; Gwinn, K.; Achterberg, S.; Algra, A.; Amouyel, P.; Anderson, C.D.; Arnett, D.K.; et al. Loci Associated with Ischaemic Stroke and Its Subtypes (SiGN): A Genome-Wide Association Study. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traylor, M.; Adib-Samii, P.; Harold, D.; Dichgans, M.; Williams, J.; Lewis, C.M.; Markus, H.S.; Fornage, M.; Holliday, E.G.; Sharma, P.; et al. Shared Genetic Contribution to Ischemic Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 79, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichgans, M.; Malik, R.; König, I.R.; Rosand, J.; Clarke, R.; Gretarsdottir, S.; Thorleifsson, G.; Mitchell, B.D.; Assimes, T.L.; Levi, C.; et al. Shared Genetic Susceptibility to Ischemic Stroke and Coronary Artery Disease. Stroke 2014, 45, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-C.; Stanne, T.M.; Giese, A.-K.; Ho, W.K.; Traylor, M.; Amouyel, P.; Holliday, E.G.; Malik, R.; Xu, H.; Kittner, S.J.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Young-Onset Stroke Identifies a Locus on Chromosome 10q25 Near HABP2. Stroke 2016, 47, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, D.A.; Buil, A.; Ziemek, D.; Martinez-Perez, A.; Malik, R.; Folkersen, L.; Germain, M.; Mälarstig, A.; Brown, A.; Soria, J.M.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Self-Reported Events in 6135 Individuals and 252 827 Controls Identifies 8 Loci Associated with Thrombosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 1867–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Chauhan, G.; Traylor, M.; Sargurupremraj, M.; Okada, Y.; Mishra, A.; Rutten-Jacobs, L.; Giese, A.-K.; van der Laan, S.W.; Gretarsdottir, S.; et al. Multiancestry Genome-Wide Association Study of 520,000 Subjects Identifies 32 Loci Associated with Stroke and Stroke Subtypes. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHGRI-GWAS GWAS Stroke Results. Available online: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/efotraits/EFO_0000712 (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Kuhn, M.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Minguez, P.; Doerks, T.; Stark, M.; Muller, J.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING Database in 2011: Functional Interaction Networks of Proteins, Globally Integrated and Scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- STRING Protein-Protein Interactions Network. Available online: https://string-db.org/ (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Universal Protein Resource UniProt. Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/ (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- STRING Score Computation. Available online: http://version10.string-db.org/help/faq/ (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Tam, V.; Patel, N.; Turcotte, M.; Bossé, Y.; Paré, G.; Meyre, D. Benefits and Limitations of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokyu, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Nanbara, H.; Sudo, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Suda, T.; Izumi, Y. Thrombospondin-1 production is enhanced by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide in THP-1 cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e0115107, Erratum in: PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simats, A.; García-Berrocoso, T.; Ramiro, L.; Giralt, D.; Gill, N.; Penalba, A.; Bustamante, A.; Rosell, A.; Montaner, J. Characterization of the rat cerebrospinal fluid proteome following acute cerebral ischemia using an aptamer-based proteomic technology. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez, N.; Aguilera, N.; Quiñónez, B.; Silva, E.; González, L.E.; Hernández, L. Arginine and glutamate levels in the gingival crevicular fluid from patients with chronic periodontitis. Braz. Dent. J. 2008, 19, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Hajishengallis, E.; Kajikawa, T.; Wang, B.; Yancopoulou, D.; Ricklin, D.; Lambris, J.D. Complement inhibition in pre-clinical models of periodontitis and prospects for clinical application. Semin. Immunol. 2016, 28, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.L.; Chou, R.H.; Shyu, W.C.; Hsieh, S.C.; Wu, C.S.; Chiang, S.Y.; Chang, W.J.; Chen, J.N.; Tseng, Y.J.; Lin, Y.H.; et al. Smurf2-mediated degradation of EZH2 enhances neuron differentiation and improves functional recovery after ischaemic stroke. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes for Stroke (Regulation) | Genes for Periodontitis (Regulation) | Score |

|---|---|---|

| CAMK2D | ACTN2 | 0.939 |

| ADAMTS12 | THSD4 | 0.918 |

| ADAMTS2 | THSD4 | 0.916 |

| SERPINA1 | ACTN1 | 0.907 |

| F5 | ACTN1 | 0.906 |

| ATG7 | SMURF2 | 0.904 |

| SERPINA1 | ACTN2 | 0.904 |

| F5 | ACTN2 | 0.903 |

| SPSB4 | SMURF2 | 0.902 |

| MCHR1 | C5AR1 | 0.900 |

| SEMA5B | THSD4 | 0.900 |

| Gene Symbol | Name | Description | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | |||

| F2 | Coagulation factor II, thrombin | Cleaves bonds after Arg and Lys, converts fibrinogen to fibrin and activates factors V, VII, VIII, XIII, and, in complex with thrombomodulin, protein C. Functions in blood homeostasis, inflammation and wound healing | Plasma and Liver |

| F5 | Coagulation factor V | Regulator of hemostasis. Is a critical cofactor for the prothrombinase activity of factor Xa that results in the activation of prothrombin to thrombin | Golgi apparatus |

| SERPINA1 | Serpin family A member 1 | Inhibitor of serine proteases | Vesicles |

| CAMK2D | Calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II delta | Involved in the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis and excitation-contraction | Plasma membrane, cytosol, cell junctions |

| ADAMTS2 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 2 | Cleaves the propeptides of type I and II collagen prior to fibril assembly (By similarity) | Plasma membrane, vesicles |

| ADAMTS12 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 12 | Metalloprotease that may play a role in the degradation of COMP. Cleaves also α-2 macroglobulin and aggregan. Has anti-tumorigenic properties | Nucleoli and mitochondria |

| ATG7 | Autophagy related 7 | Involved in the 2 ubiquitin-like systems required for cytoplasm to vacuole transport (Cvt) and autophagy | Cytosol, Plasma membrane, Nucleoplasm |

| SPSB4 | SplA/ryanodine receptor domain and SOCS box containing 4 | Mediates the ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of target proteins | Nucleoplasm and Golgi apparatus |

| MCHR1 | Melanin concentrating hormone receptor 1 | Receptor for melanin-concentrating hormone | Not available |

| FGG | Fibrinogen γ chain | With fibrinogen α (FGA) and fibrinogen β (FGB), polymerizes to form an insoluble fibrin matrix. Has a major function in haemostasis as one of the primary components of blood clots | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| SEMA5B | Semaphorin 5B | Acts as positive axonal guidance cues | Cytosol |

| Periodontitis | |||

| TIMP1 | TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 | Growth factor, Metalloenzyme inhibitor, Metalloprotease inhibitor, Protease inhibitor | Golgi apparatus |

| ACTN1 | Actinin α 1 | F-actin cross-linking protein which is thought to anchor actin to a variety of intracellular structures | Actin filaments |

| ACTN2 | Actinin α 2 | F-actin cross-linking protein which is thought to anchor actin to a variety of intracellular structures | Actin filaments |

| THSD4 | Thrombospondin type 1 domain containing 4 | Promotes FBN1 matrix assembly | Extracellular matrix |

| SMURF2 | E3 ubiquitin–protein ligase SMURF2 | Involved in the transfer of the ubiquitin to targeted substrates. Interacts with SMAD1 and SMAD7 triggering ubiquitination and degradation. | Plasma Membrane, Nucleus Cytoplasm, Membrane Raft |

| C5AR1 | Complement C5a receptor 1 | Receptor for the chemotactic and inflammatory peptide anaphylatoxin C5a | Golgi apparatus and vesicles |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leira, Y.; Mascarenhas, P.; Blanco, J.; Sobrino, T.; Mendes, J.J.; Machado, V.; Botelho, J. Network Protein Interaction in the Link between Stroke and Periodontitis Interplay: A Pilot Bioinformatic Analysis. Genes 2021, 12, 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050787

Leira Y, Mascarenhas P, Blanco J, Sobrino T, Mendes JJ, Machado V, Botelho J. Network Protein Interaction in the Link between Stroke and Periodontitis Interplay: A Pilot Bioinformatic Analysis. Genes. 2021; 12(5):787. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050787

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeira, Yago, Paulo Mascarenhas, Juan Blanco, Tomás Sobrino, José João Mendes, Vanessa Machado, and João Botelho. 2021. "Network Protein Interaction in the Link between Stroke and Periodontitis Interplay: A Pilot Bioinformatic Analysis" Genes 12, no. 5: 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050787

APA StyleLeira, Y., Mascarenhas, P., Blanco, J., Sobrino, T., Mendes, J. J., Machado, V., & Botelho, J. (2021). Network Protein Interaction in the Link between Stroke and Periodontitis Interplay: A Pilot Bioinformatic Analysis. Genes, 12(5), 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050787