Genetic Biomarkers of Panic Disorder: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

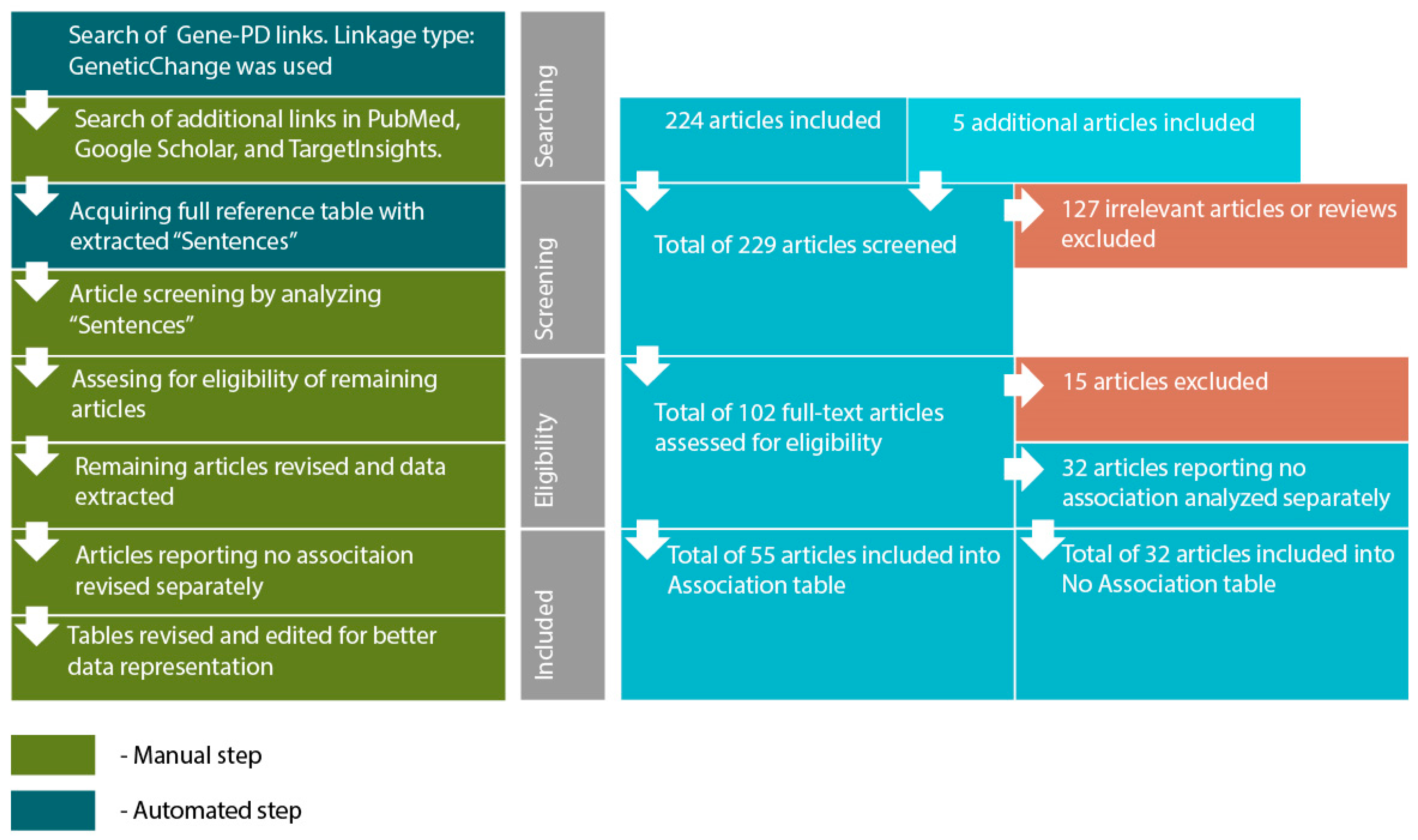

2. Materials and Methods

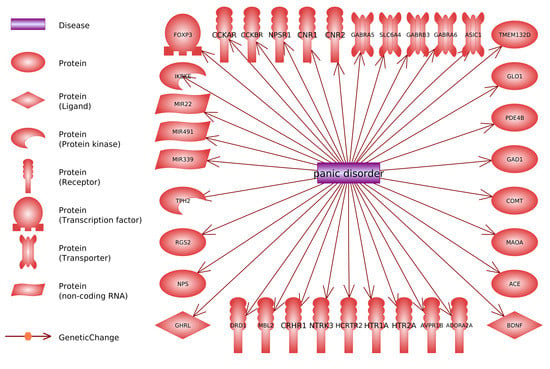

- Searching for genes (proteins) linked to PD through reported polymorphism associations. The initial list of genes was acquired using PathwayStudio 12.3 software. Search was performed by adding “Panic Disorder” object and extracting all proteins and complexes linked to “Panic Disorder”. Linkage type: GeneticChange was used. This type allows to search for reported polymorphism-condition associations. In accordance to ResNet and Pathway Studio features, the acquired list included not only protein-encoding genes but microRNA-encoding genes as well, if they are reportedly linked to PD.

- Acquiring a reference table via “View relation table”. This function provides access to reference IDs and data-mined “Sentences” containing association reports from original articles. On this step additional search was performed using PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), TargetInsights (https://demo.elseviertextmining.com/) and GoogleScholar (https://scholar.google.ru/). A total of 229 references supporting each gene-PD link were identified and taken into further screening.

- Screening was performed by manually analyzing “Sentences” extracted by Pathway Studio from full-text articles. All Sentences were carefully revised by at least three authors, full texts were manually studied for additional details, if necessary. All irrelevant studies identified in this step were excluded from further analysis. A total of 127 irrelevant studies were identified, including 50 literature reviews with no original experiments; 50 articles on irrelevant topics misinterpreted by text-mining algorithms; 27 studies involving model organisms, and lacking human patient studies.

- Full texts of 102 remaining articles were manually revised and assessed for eligibility by authors. Original research papers with statistically significant results were taken into the further analysis: positive association of certain gene modification (or one of its variants) with the disease; interaction with another gene; association of genotypes or alleles of different genes; the presence of the mutation in families with high occurrence of the disease; cosegregation of genetic alteration with manifestations of the disease.

- All articles reporting lack of association were transferred into a separate “No Association” table. This table was analyzed separately (see Step 6). This also included studies reporting an association with the particular symptoms but no association with the disorder in general. A total of 32 articles were excluded due to a lack of significant association.

- All remaining articles reporting results irrelevant to our study (i.e., treatment response studies) were excluded. A total of 15 articles were excluded due to these reasons.

- The remaining 55 articles formed the basis of our review. Each paper was manually studied for association availability (significance was assessed by revising p-values). Official gene names, polymorphism IDs, sample sizes, p-values for each association, and other relevant data were manually extracted and revised. All articles reporting significant associations were considered eligible. Small sample size was not considered an exclusion criterion. However, we are aware that the sample size may result in significant bias. To allow estimating this bias we provide sample sizes in the Sample column.

- After analyzing the articles reporting associations, we performed a manual analysis of the “No Association” table. The analysis was performed by additional full-text revision and extraction of relevant data.

3. Results

4. Discussion

- 13%—involved in the regulation of the work of genes (including miRNA); FOXP3, IKBKE, MIR22, MIR339, MIR491.

- 10%—involved in the reception of extracellular signals and system of secondary messengers functioning; NTRK3, PDE4B, RGS2, TMEM132D.

- 5%—involved in the general functioning of neurons; ASIC1, BDNF.

- 5%—not fitting to any of these categories others; GLO1, MBL2.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kessler, R.C.; Chiu, W.T.; Jin, R.; Ruscio, A.M.; Shear, K.; Walters, E.E. The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, S.E.; Yonkers, K.A.; Otto, M.W.; Eisen, J.L.; Weisberg, R.B.; Pagano, M.; Shea, M.T.; Keller, M.B. Influence of Psychiatric Comorbidity on Recovery and Recurrence in Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Phobia, and Panic Disorder: A 12-Year Prospective Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidoff, J.; Christensen, S.; Khalili, D.N.; Nguyen, J.; IsHak, W.W. Quality of life in panic disorder: Looking beyond symptom remission. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherbourne, C.D.; Wells, K.B.; Judd, L.L. Functioning and well-being of patients with panic disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1996, 153, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, W.W.; Kessler, R.C.; Wittchen, H.U.; Magee, W.J. Panic and panic disorder in the United States. Am. J. Psychiatry 1994, 151, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettema, J.M.; Neale, M.C.; Kendler, K.S. A Review and Meta-Analysis of the Genetic Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1568–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, R.R.; Noyes, R.; Pauls, D.L.; Slymen, D. A family study of panic disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1983, 40, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.B.; Wickramaratne, P.J.; Horwath, E.; Weissman, M.M. Familial aggregation and phenomenology of “early”-onset (at or before age 20 years) panic disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, N.B.; Trakowski, J.H.; Staab, J.P. Extinction of panicogenic effects of a 35% CO2 challenge in patients with panic disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1997, 106, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelow, B.; Saleh, K.; Pauls, J.; Domschke, K.; Wedekind, D.; Falkai, P. Insertion/deletion polymorphism in the gene for angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in panic disorder: A gender-specific effect? World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 11, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulec-Yılmaz, S.; Gulec, H.; Dalan, A.B.; Cetın, B.; Tımırcı-Kahraman, O.; Ogut, D.B.; Atasoy, H.; Dırımen, G.A.; Gultekın, G.I.; Isbır, T. The relationship between ACE polymorphism and panic disorder. In Vivo 2014, 28, 885–889. [Google Scholar]

- Gugliandolo, A.; Gangemi, C.; Caccamo, D.; Currò, M.; Pandolfo, G.; Quattrone, D.; Crucitti, M.; Zoccali, R.A.; Bruno, A.; Muscatello, M.R.A. The RS685012 Polymorphism of ACCN2, the Human Ortholog of Murine Acid-Sensing Ion Channel (ASIC1) Gene, is Highly Represented in Patients with Panic Disorder. Neuromol. Med. 2016, 18, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohoff, C.; Mullings, E.L.; Heatherley, S.V.; Freitag, C.M.; Neumann, L.C.; Domschke, K.; Krakowitzky, P.; Rothermundt, M.; Keck, M.E.; Erhardt, A.; et al. Adenosine A(2A) receptor gene: Evidence for association of risk variants with panic disorder and anxious personality. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 44, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smoller, J.W.; Gallagher, P.J.; Duncan, L.E.; McGrath, L.M.; Haddad, S.A.; Holmes, A.J.; Wolf, A.B.; Hilker, S.; Block, S.R.; Weill, S.; et al. The human ortholog of acid-sensing ion channel gene ASIC1a is associated with panic disorder and amygdala structure and function. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 76, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keck, M.E.; Kern, N.; Erhardt, A.; Unschuld, P.G.; Ising, M.; Salyakina, D.; Müller, M.B.; Knorr, C.C.; Lieb, R.; Hohoff, C.; et al. Combined effects of exonic polymorphisms in CRHR1 and AVPR1B genes in a case/control study for panic disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008, 147B, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.-J.; Kim, Y.-K.; Hwang, J.-A.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, H.-J.; Yoon, H.-K.; Na, K.-S. Evidence for Association between the Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Gene and Panic Disorder: A Novel Haplotype Analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 2015, 12, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, E.; Ebihara, M.; Yamada, K.; Ohba, H.; Shibuya, H.; Yoshikawa, T. Identification of a compound short tandem repeat stretch in the 5’-upstream region of the cholecystokinin gene, and its association with panic disorder but not with schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 2001, 6, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, E.; Nikopensius, T.; Kõks, S.; Altmäe, S.; Heinaste, E.; Vabrit, K.; Tammekivi, V.; Hallast, P.; Koido, K.; Kurg, A.; et al. Association study of 90 candidate gene polymorphisms in panic disorder. Psychiatr. Genet. 2005, 15, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Matsushita, S.; Higuchi, S.; Shirakawa, O.; Shimokata, H.; Funakoshi, A. Association of cholecystokinin-A receptor gene polymorphisms and panic disorder in Japanese. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2004, 127B, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hösing, V.G.; Schirmacher, A.; Kuhlenbäumer, G.; Freitag, C.; Sand, P.; Schlesiger, C.; Jacob, C.; Fritze, J.; Franke, P.; Rietschel, M.; et al. Cholecystokinin- and cholecystokinin-B-receptor gene polymorphisms in panic disorder. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 2004, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.L.; Bradwejn, J.; Koszycki, D.; King, N.; Crowe, R.; Vincent, J.; Fourie, O. Investigation of cholecystokinin system genes in panic disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 1999, 4, 284–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, A.M.; García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Planelles, B.; Femenía, T.; Mingote, C.; Jiménez-Treviño, L.; Martínez-Barrondo, S.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Saiz, P.A.; Bobes, J.; et al. Association of cannabinoid receptor genes (CNR1 and CNR2) polymorphisms and panic disorder. Anxiety Stress Coping 2020, 33, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.P.; Slager, S.L.; Heiman, G.A.; Deng, Z.; Haghighi, F.; Klein, D.F.; Hodge, S.E.; Weissman, M.M.; Fyer, A.J.; Knowles, J.A. Evidence for a susceptibility locus for panic disorder near the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene on chromosome 22. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 51, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Akiyoshi, J.; Muronaga, M.; Masuda, K.; Aizawa, S.; Hirakawa, H.; Ishitobi, Y.; Higuma, H.; Maruyama, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; et al. Association of TMEM132D, COMT, and GABRA6 genotypes with cingulate, frontal cortex and hippocampal emotional processing in panic and major depressive disorder. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2015, 19, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.-M.; Yoon, K.-S.; Choi, Y.-H.; Oh, K.-S.; Lee, Y.-S.; Yu, B.-H. The association between panic disorder and the L/L genotype of catechol-O-methyltransferase. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2004, 38, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.-M.; Yoon, K.-S.; Yu, B.-H. Catechol O-methyltransferase genetic polymorphism in panic disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1785–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rothe, C.; Koszycki, D.; Bradwejn, J.; King, N.; Deluca, V.; Tharmalingam, S.; Macciardi, F.; Deckert, J.; Kennedy, J.L. Association of the Val158Met catechol O-methyltransferase genetic polymorphism with panic disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 2237–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asselmann, E.; Hertel, J.; Beesdo-Baum, K.; Schmidt, C.-O.; Homuth, G.; Nauck, M.; Grabe, H.-J.; Pané-Farré, C.A. Interplay between COMT Val158Met, childhood adversities and sex in predicting panic pathology: Findings from a general population sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 234, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettema, J.M.; An, S.-S.; Bukszar, J.; van den Oord, E.J.C.G.; Neale, M.C.; Kendler, K.S.; Chen, X. Catechol-O-methyltransferase contributes to genetic susceptibility shared among anxiety spectrum phenotypes. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 64, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Karacetin, G.; Bayoglu, B.; Cengiz, M.; Demir, T.; Kocabasoglu, N.; Uysal, O.; Bayar, R.; Balcioglu, I. Serotonin-2A receptor and catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphisms in panic disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 36, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domschke, K.; Freitag, C.M.; Kuhlenbäumer, G.; Schirmacher, A.; Sand, P.; Nyhuis, P.; Jacob, C.; Fritze, J.; Franke, P.; Rietschel, M.; et al. Association of the functional V158M catechol-O-methyl-transferase polymorphism with panic disorder in women. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004, 7, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, H.; Richter, J.; Straube, B.; Lueken, U.; Domschke, K.; Schartner, C.; Klauke, B.; Baumann, C.; Pané-Farré, C.; Jacob, C.P.; et al. Allelic variation in CRHR1 predisposes to panic disorder: Evidence for biased fear processing. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoeringer, C.K.; Binder, E.B.; Salyakina, D.; Erhardt, A.; Ising, M.; Unschuld, P.G.; Kern, N.; Lucae, S.; Brueckl, T.M.; Mueller, M.B.; et al. Association of a Met88Val diazepam binding inhibitor (DBI) gene polymorphism and anxiety disorders with panic attacks. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2007, 41, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelog, M.; Hilligardt, D.; Schmidt, C.A.; Przybylski, G.K.; Leierer, J.; Almanzar, G.; El Hajj, N.; Lesch, K.-P.; Arolt, V.; Zwanzger, P.; et al. Hypermethylation of FOXP3 Promoter and Premature Aging of the Immune System in Female Patients with Panic Disorder? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, L.M.; Fyer, A.J.; Weissman, M.M.; Logue, M.W.; Haghighi, F.; Evgrafov, O.; Rotondo, A.; Knowles, J.A.; Hamilton, S.P. Evidence for linkage and association of GABRB3 and GABRA5 to panic disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domschke, K.; Tidow, N.; Schrempf, M.; Schwarte, K.; Klauke, B.; Reif, A.; Kersting, A.; Arolt, V.; Zwanzger, P.; Deckert, J. Epigenetic signature of panic disorder: A role of glutamate decarboxylase 1 (GAD1) DNA hypomethylation? Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 46, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, H.; Scholz, C.J.; Domschke, K.; Baumann, C.; Klauke, B.; Jacob, C.P.; Maier, W.; Fritze, J.; Bandelow, B.; Zwanzger, P.M.; et al. Gender differences in associations of glutamate decarboxylase 1 gene (GAD1) variants with panic disorder. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, C.; Annerbrink, K.; Nilsson, S.; Bah, J.; Olsson, M.; Allgulander, C.; Andersch, S.; Sjödin, I.; Eriksson, E.; Dickson, S.L. A possible association between panic disorder and a polymorphism in the preproghrelingene. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 206, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, P.; Minoretti, P.; Falcone, C.; Martinelli, V.; Emanuele, E. Association analysis of the functional Ala111Glu polymorphism of the glyoxalase I gene in panic disorder. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 396, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annerbrink, K.; Westberg, L.; Olsson, M.; Andersch, S.; Sjödin, I.; Holm, G.; Allgulander, C.; Eriksson, E. Panic disorder is associated with the Val308Iso polymorphism in the hypocretin receptor gene. Psychiatr. Genet. 2011, 21, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaya, C.; Salum, G.A.; Moorjani, P.; Seganfredo, A.C.; Heldt, E.; Leistner-Segal, S.; Smoller, J.W.; Manfro, G.G. Panic disorder and serotonergic genes (SLC6A4, HTR1A and HTR2A): Association and interaction with childhood trauma and parenting. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 485, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Ishiguro, S.; Aoki, A.; Ueda, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Akiyama, K.; Kato, K.; Shimoda, K. Genetic Polymorphism of 1019C/G (rs6295) Promoter of Serotonin 1A Receptor and Catechol-O-Methyltransferase in Panic Disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2017, 14, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, Y.; Yoneda, H.; Koh, J.; Sakai, J.; Himei, A.; Kinoshita, Y.; Akabame, K.; Hiraoka, Y.; Sakai, T. Positive association between panic disorder and polymorphism of the serotonin 2A receptor gene. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 118, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koido, K.; Eller, T.; Kingo, K.; Kõks, S.; Traks, T.; Shlik, J.; Vasar, V.; Vasar, E.; Maron, E. Interleukin 10 family gene polymorphisms are not associated with major depressive disorder and panic disorder phenotypes. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 44, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traks, T.; Koido, K.; Balõtšev, R.; Eller, T.; Kõks, S.; Maron, E.; Tõru, I.; Shlik, J.; Vasar, E.; Vasar, V. Polymorphisms of IKBKE gene are associated with major depressive disorder and panic disorder. Brain Behav. 2015, 5, e00314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domschke, K.; Tidow, N.; Kuithan, H.; Schwarte, K.; Klauke, B.; Ambrée, O.; Reif, A.; Schmidt, H.; Arolt, V.; Kersting, A.; et al. Monoamine oxidase A gene DNA hypomethylation—a risk factor for panic disorder? Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 15, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, C.; Richter, J.; Mahr, M.; Gajewska, A.; Schiele, M.A.; Gehrmann, A.; Schmidt, B.; Lesch, K.-P.; Lang, T.; Helbig-Lang, S.; et al. MAOA gene hypomethylation in panic disorder-reversibility of an epigenetic risk pattern by psychotherapy. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldager, L.; Köhler, O.; Steffensen, R.; Thiel, S.; Kristensen, A.S.; Jensenius, J.C.; Mors, O. Bipolar and panic disorders may be associated with hereditary defects in the innate immune system. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 164, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muiños-Gimeno, M.; Espinosa-Parrilla, Y.; Guidi, M.; Kagerbauer, B.; Sipilä, T.; Maron, E.; Pettai, K.; Kananen, L.; Navinés, R.; Martín-Santos, R.; et al. Human microRNAs miR-22, miR-138-2, miR-148a, and miR-488 are associated with panic disorder and regulate several anxiety candidate genes and related pathways. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, K.-M.; Kim, H.S.; An, H.J.; Kim, J.O.; Choi, T.K.; Kim, N.K.; Lee, S.-H. Association of human microRNAs miR-22 and miR-491 polymorphisms with panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in a Korean population. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 188, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, J.; Haapakoski, R.; Ezer, S.; Melén, E.; Pirkola, S.; Gratacòs, M.; Zucchelli, M.; Anedda, F.; Johansson, L.E.; Söderhäll, C.; et al. Assessment of the neuropeptide S system in anxiety disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, N.; Hashimoto, K.; Iyo, M.; Shimizu, E.; Dempfle, A.; Friedel, S.; Reinscheid, R.K. Gender-specific association of a functional coding polymorphism in the Neuropeptide S receptor gene with panic disorder but not with schizophrenia or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 31, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengol, L.; Gratacòs, M.; Pujana, M.A.; Ribasés, M.; Martín-Santos, R.; Estivill, X. 5’ UTR-region SNP in the NTRK3 gene is associated with panic disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2002, 7, 928–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Yamada, K.; Iwayama, Y.; Toyota, T.; Furukawa, A.; Takimoto, T.; Terayama, H.; Iwahashi, K.; Takei, N.; Minabe, Y.; et al. Evidence that variation in the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) gene influences susceptibility to panic disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2006, 141B, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otowa, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Sugaya, N.; Yoshida, E.; Shimada, T.; Liu, X.; Tochigi, M.; Umekage, T.; Miyagawa, T.; Nishida, N.; et al. Association study of PDE4B with panic disorder in the Japanese population. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 35, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakhova, A.V.; Rudko, O.I.; Sobolev, V.V.; Tretiakov, A.V.; Naumova, E.A.; Kokaeva, Z.G.; Azimova, J.E.; Klimov, E.A. PDE4B gene polymorphism in Russian patients with panic disorder. AIMS Genet. 2019, 6, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.-P.; Westberg, L.; Annerbrink, K.; Olsson, M.; Melke, J.; Nilsson, S.; Baghaei, F.; Rosmond, R.; Holm, G.; Björntorp, P.; et al. Association between a functional polymorphism in the progesterone receptor gene and panic disorder in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004, 29, 1138–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohoff, C.; Weber, H.; Richter, J.; Domschke, K.; Zwanzger, P.M.; Ohrmann, P.; Bauer, J.; Suslow, T.; Kugel, H.; Baumann, C.; et al. RGS2 ggenetic variation: Association analysis with panic disorder and dimensional as well as intermediate phenotypes of anxiety. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2015, 168B, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckert, J.; Meyer, J.; Catalano, M.; Bosi, M.; Sand, P.; DiBella, D.; Ortega, G.; Stöber, G.; Franke, P.; Nöthen, M.M.; et al. Novel 5’-regulatory region polymorphisms of the 5-HT2C receptor gene: Association study with panic disorder. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000, 3, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttenschøn, H.N.; Kristensen, A.S.; Buch, H.N.; Andersen, J.H.; Bonde, J.P.; Grynderup, M.; Hansen, A.M.; Kolstad, H.; Kaergaard, A.; Kaerlev, L.; et al. The norepinephrine transporter gene is a candidate gene for panic disorder. J. Neural Transm. 2011, 118, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Lee, H.-J.; Yang, J.-C.; Hwang, J.-A.; Yoon, H.-K. A tryptophan hydroxylase 2 gene polymorphism is associated with panic disorder. Behav. Genet. 2009, 39, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada-Sugimoto, M.; Otowa, T.; Miyagawa, T.; Khor, S.-S.; Omae, Y.; Toyo-Oka, L.; Sugaya, N.; Kawamura, Y.; Umekage, T.; Miyashita, A.; et al. Polymorphisms in the TMEM132D region are associated with panic disorder in HLA-DRB1*13:02-negative individuals of a Japanese population. Hum. Genome Var. 2016, 3, 16001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erhardt, A.; Czibere, L.; Roeske, D.; Lucae, S.; Unschuld, P.G.; Ripke, S.; Specht, M.; Kohli, M.A.; Kloiber, S.; Ising, M.; et al. TMEM132D, a new candidate for anxiety phenotypes: Evidence from human and mouse studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, A.; Akula, N.; Schumacher, J.; Czamara, D.; Karbalai, N.; Müller-Myhsok, B.; Mors, O.; Borglum, A.; Kristensen, A.S.; Woldbye, D.P.D.; et al. Replication and meta-analysis of TMEM132D gene variants in panic disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2012, 2, e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, E.; Hashimoto, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Mitsumori, M.; Ohgake, S.; Koizumi, H.; Okamura, N.; Koike, K.; Kumakiri, C.; Nakazato, M.; et al. Lack of association between angiotensin I-converting enzyme insertion/deletion gene functional polymorphism and panic disorder in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 2004, 363, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoglu, B.; Cengiz, M.; Karacetin, G.; Uysal, O.; Kocabasoğlu, N.; Bayar, R.; Balcioglu, I. Genetic polymorphism of angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE), but not angiotensin II type I receptor (ATr1), has a gender-specific role in panic disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 66, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.; Hong, C.-J.; Tsai, S.-J. Association study of A2a adenosine receptor genetic polymorphism in panic disorder. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 378, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.P.; Slager, S.L.; De Leon, A.B.; Heiman, G.A.; Klein, D.F.; Hodge, S.E.; Weissman, M.M.; Fyer, A.J.; Knowles, J.A. Evidence for genetic linkage between a polymorphism in the adenosine 2A receptor and panic disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, N.; Dahl, H.A.; Buttenschøn, H.N.; Nyegaard, M.; Hedemand, A.; Als, T.D.; Wang, A.G.; Joensen, S.; Woldbye, D.P.; Koefoed, P.; et al. A genome-wide study of panic disorder suggests the amiloride-sensitive cation channel 1 as a candidate gene. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 20, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, E.; Hashimoto, K.; Koizumi, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Itoh, K.; Mitsumori, M.; Ohgake, S.; Okamura, N.; Koike, K.; Matsuzawa, D.; et al. No association of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene polymorphisms with panic disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 29, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, A.; Lucae, S.; Unschuld, P.G.; Ising, M.; Kern, N.; Salyakina, D.; Lieb, R.; Uhr, M.; Binder, E.B.; Keck, M.E.; et al. Association of polymorphisms in P2RX7 and CaMKKb with anxiety disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 101, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Ding, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, X.; Tang, J. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of miR-22 in regulating malignant progression in human cancer (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 50, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, E.; Yamada, K.; Toyota, T.; Yoshitsugu, K.; Toru, M.; Shibuya, H.; Yoshikawa, T. Association studies of the CT repeat polymorphism in the 5’ upstream region of the cholecystokinin B receptor gene with panic disorder and schizophrenia in Japanese subjects. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 105, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinlein, O.K.; Deckert, J.; Nöthen, M.M.; Franke, P.; Maier, W.; Beckmann, H.; Propping, P. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 subunit (CHRNA4) and panic disorder: An association study. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997, 74, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Yoo, E.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, K.S.; Choe, A.Y.; Lee, J.E.; Kwack, K.; Yook, K.-H.; Choi, T.K.; Lee, S.-H. The effects of the catechol-O-methyltransferase val158met polymorphism on white matter connectivity in patients with panic disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 147, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska-Mazur, J.; Grzywacz, A.; Samochowiec, J.; Samochowiec, A.; Hajduk, A.; Bieńkowski, P. Haplotype analysis at DRD2 locus in patients with panic disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 179, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philibert, R.A.; Nelson, J.J.; Bedell, B.; Goedken, R.; Sandhu, H.K.; Noyes, R.; Crowe, R.R. Role of elastin polymorphisms in panic disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2003, 117B, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, R.R.; Wang, Z.; Noyes, R.; Albrecht, B.E.; Darlison, M.G.; Bailey, M.E.; Johnson, K.J.; Zoëga, T. Candidate gene study of eight GABAA receptor subunits in panic disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-S.; Lee, B.-H.; Yang, J.-C.; Kim, Y.-K. Association Study between 5-HT1A Receptor Gene C(-1019)G Polymorphism and Panic Disorder in a Korean Population. Psychiatry Investig. 2010, 7, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, A.Y.; Kim, B.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, J.-Y.; Choi, T.K.; Lee, S.-H. Serotonergic genes (5-HTT and HTR1A) and separation life events: Gene-by-environment interaction for panic disorder. Neuropsychobiology 2013, 67, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.-K.; Yang, J.-C.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, Y.-K. The association between serotonin-related gene polymorphisms and panic disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2008, 22, 1529–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, C.; Schleicher, A.; Szegedi, A.; Anghelescu, I.; Klawe, C.; Hiemke, C.; Dahmen, N. Serotonergic polymorphisms in patients suffering from alcoholism, anxiety disorders and narcolepsy. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 25, 965–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unschuld, P.G.; Ising, M.; Erhardt, A.; Lucae, S.; Kloiber, S.; Kohli, M.; Salyakina, D.; Welt, T.; Kern, N.; Lieb, R.; et al. Polymorphisms in the serotonin receptor gene HTR2A are associated with quantitative traits in panic disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007, 144B, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Kim, Y.-K. The G allele in IL-10-1082 G/A may have a role in lowering the susceptibility to panic disorder in female patients. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2016, 28, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koido, K.; Traks, T.; Balõtšev, R.; Eller, T.; Must, A.; Koks, S.; Maron, E.; Tõru, I.; Shlik, J.; Vasar, V.; et al. Associations between LSAMP gene polymorphisms and major depressive disorder and panic disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2012, 2, e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadic, A.; Rujescu, D.; Szegedi, A.; Giegling, I.; Singer, P.; Möller, H.-J.; Dahmen, N. Association of a MAOA gene variant with generalized anxiety disorder, but not with panic disorder or major depression. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2003, 117B, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouri, K.; Hishimoto, A.; Fukutake, M.; Nishiguchi, N.; Shirakawa, O.; Maeda, K. Association study of RGS2 gene polymorphisms with panic disorder in Japanese. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 2010, 55, E116–E121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Choi, Y.H.; Yoon, K.-S.; Cho, D.-Y.; Pae, C.-U.; Woo, J.-M. Tryptophan hydroxylase and serotonin transporter gene polymorphism does not affect the diagnosis, clinical features and treatment outcome of panic disorder in the Korean population. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 30, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckert, J.; Catalano, M.; Heils, A.; Di Bella, D.; Friess, F.; Politi, E.; Franke, P.; Nöthen, M.M.; Maier, W.; Bellodi, L.; et al. Functional promoter polymorphism of the human serotonin transporter: Lack of association with panic disorder. Psychiatr. Genet. 1997, 7, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, G.; di Bella, D.; Favaron, E.; Cucchi, M.; Liperi, L.; Bellodi, L. Lack of relationship between CO2 reactivity and serotonin transporter gene regulatory region polymorphism in panic disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2004, 129B, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachleski, C.; Blaya, C.; Salum, G.A.; Vargas, V.; Leistner-Segal, S.; Manfro, G.G. Lack of association between the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and personality traits in asymptomatic patients with panic disorder. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 431, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mössner, R.; Freitag, C.M.; Gutknecht, L.; Reif, A.; Tauber, R.; Franke, P.; Fritze, J.; Wagner, G.; Peikert, G.; Wenda, B.; et al. The novel brain-specific tryptophan hydroxylase-2 gene in panic disorder. J. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 20, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Song, I.H.; Lee, S.-H. Gender Differences of Stressful Life Events, Coping Style, Symptom Severity, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Panic Disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017, 205, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldirola, D.; Alciati, A.; Riva, A.; Perna, G. Are there advances in pharmacotherapy for panic disorder? A systematic review of the past five years. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2018, 19, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, G.; Grassi, M.; Caldirola, D.; Nemeroff, C.B. The revolution of personalized psychiatry: Will technology make it happen sooner? Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene 1 | Possible PD Link 2 | Marker 3 | Sample 4 | Commentary 5 | Reference 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE (angiotensin I converting enzyme) | ACE peptidase degrades a number of neuropeptides possibly involved in the development of anxious behavior. | rs4646994 | nP = 102 (59 female, 43 male), nC = 102 (59 female, 43 male). Germany. | Less active Ins (p = 0.0474) allele and genotypes containing Ins (p = 0.0195) are associated with PD in male subsample. | [10] |

| rs4646994 | nP = 43 (28 female and 15 male), nC = 41 (17 female and 24 male). Turkey. | Allele Ins is more frequent in patients (p = 0.002). Genotype ID is associated with PD (p = 0.003). Patients with allele D had higher risk of respiratory type PD (p = 0.034). | [11] | ||

| ADORA2A (adenosine A2a receptor) | Transmembrane adenosine receptor. Participates in the vasodilation and increasing of neurotransmitter release, which occurs during panic attacks. | rs2298383 and rs685012 (ASIC1) | nP = 71 (20 male, 51 female), nC = 100 (37 male, 63 female). Sicily, Italy. | Haplotype rs685012:TT (ASIC1) + rs2298383:CT (ADORA2A) is more frequent in controls (p = 0.026). See also ASIC1. | [12] |

| rs5751876, rs5751862, rs2298383, rs3761422, rs5760405, rs2267076 | nP = 457 (167 male, 290 female), nC = 457 (167 male, 290 female). Germany. | Genotype rs5751876:TT is associated with PD and PD with agoraphobia (p = 0.032, p = 0.012 respectively). Haplotype GCGCCTTT (rs2298383:C, rs3761422:T, rs5751876:T) is found to be risk (p = 0.005), carriers of this haplotype showed higher anxiety levels. Haplotype ATGCTCCC (rs5751862:A, rs2298383:T, rs3761422:C, rs5751876:C), is found to be protective (p = 0.006). Allele carriers of rs5751862:G, rs2298383:C, rs3761422:T showed higher levels of anxiety than rs5751862:AA, rs2298383:TT and rs3761422:CC carriers (p = 0.001, p = 0.002, p = 0.002, respectively). A total of 8 SNPs studied. | [13] | ||

| ASIC1 (acid-sensing ion channel subunit 1) | ASIC1 protonsensitive channel is expressed throughout the nervous system and is involved in the formation of fear, anxiety, pain, depression, memory, and learning processes. | rs685012, rs10875995 | nP = 414 (232 female, 182 male), nC = 846 (474 female, 372 male). European-American, European-Brazilian. | Alleles rs685012:C and rs10875995:C are more frequent in patients (p = 0.0093, p = 0.047 respectively). The association is enhanced by a separate analysis of respiratory subtype PD subsample and early development (less than 20 years of age) PD subsample (p = 0.027). Neither rs685012 nor rs10875995 was associated with PD in non-respiratory-subtype subsample (n = 87) (both p > 0.70). | [14] |

| rs685012 and rs2298383 (ADORA2A) | nP = 71 (20 male, 51 female), nC = 100 (37 male, 63 female). Sicily, Italy. | Allele rs685012:C is more frequent in patients (p = 0.030). Haplotype rs685012:TT (ASIC1) + rs2298383:CT (ADORA2A) is more frequent in controls (p = 0.026). See also ADORA2A. | [12] | ||

| AVPR1B (arginine vasopressin receptor 1B) | Arginine receptor which is found in the anterior pituitary and brain structures. Plays a decisive role in modulating the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and homeostasis during stress. | rs28632197 and rs878886 (CRHR1) | (1) nP = 186 (128 female, 58 male), nC = 299 (217 female, 82 male). Germany. (2) nP = 173 (68 male, 105 female), nC = 495 (195 male, 300 female). Germany. | Genotype-allele haplotype rs28632197:TT (AVPR1B) + rs878886:G (CRHR1) shows strongest association with PD (p = 0.00057). 15 more associations below the significance threshold found. | [15] |

| BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) | BDNF is one of the most abundant neurotrophins found in brain tissues. It regulates neuronal plasticity: the formation and maintenance of synaptic contacts. May be involved in the pathogenesis of mental diseases including major depression and PD. | rs6265, rs16917204 | nP = 136, nC = 263. South Korea. | Haplotype GC (rs6265:G, rs16917204:C) is more frequent in patients (p = 0.0009). No association with single SNPs. A total of 3 SNPs studied. | [16] |

| CCK (cholecystokinin) | Cholecystokinins are neuropeptides that play role in satiety and anxiety. CCK-4 tetrapeptide′s ability to induce symptoms of panic attacks is known. | −345g > C | nP = 73 (40 males, 33 females), nC = 252 (133 males, 120 females), Tokyo, Japan. | Rare −345G > C SNP is associated with PD (p = 0.025). Other studied SNPs (−36c > t and −188a > g) showed no association. | [17] |

| −45C > T, 1270C > G and rs6313, 1438A-G (5HTR2A), −94G-A, −800T-C, −48G-A (DRD1) | nP = 127 (23 males, 104 females), nC = 146 (37 males, 109 females). Estonia. | Haplotype TG (−45C-T, 1270C-G) is more frequent in patients (p = 0.04). No associations with single SNPs. A total of 90 SNPs studied. See also 5HTR2A and DRD1. | [18] | ||

| CCKAR (cholecystokinin A receptor) | Cholecystokinin A receptor may be involved in the development of PD. Its agonists are known to produce most of the classic symptoms of a panic attack in PD patients. | rs1799723, rs1800908 | nP = 109 (64 males, 45 females), nC = 400 (234 males, 166 females). Japan. | Haplotype GT (rs1799723:G, rs1800908:T (−81G/−128T)) is more frequent in patients (p < 0.0001). No associations with single SNPs. | [19] |

| CCKBR (cholecystokinin B receptor) | One of the cholecystokinin receptors. Its agonists are known to produce most of the classic symptoms of a panic attack in PD patients. | CT repeat | nP = 111 (71 females, 40 males), nC = 111 (71 females, 40 males). Germany | Diallelic (short (146–162 bp), long (164–180 bp)) analysis: long allele is associated with PD in complete sample (p = 0.001); PD with agoraphobia (p = 0.002). | [20] |

| G > A in the 5′area of the 3′ untranslated region | nP = 99 (63 females, 36 males), nC = 99 (63 females, 36 males). Toronto. | SNP is associated with PD (p = 0.004). An analysis using all alleles was also significant (p = 0.038). A total of 16 alleles of CCKBR and several CCK and CCKAR polymorphisms were studied. | [21] | ||

| CNR1 (cannabinoid receptor 1) | Endocannabinoid system may play role in the regulation of stress, anxiety, depression, and addictive disorders. | rs12720071, rs806368 and rs2501431, rs2501432 (CNR2) | nP = 164 (71% female), nC = 320 (71% female). Spain. | Allele rs12720071:G is associated with PD (p = 0.012) and more frequent in females. Total of 12 SNPs studied. See also CNR2. | [22] |

| CNR2 (cannabinoid receptor 2) | rs2501431, rs2501432 and rs12720071, rs806368 (CNR1) | nP = 164 (71% female), nC = 320 (71% female). Spain. | Allele rs2501431:G showed protective effect in male carriers of haplotype A592G (rs2501431) + C315T (rs2501432)) (p = 0.043). A total of 12 SNPs were studied. See also CNR1. | [22] | |

| COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) | COMT enzyme is involved in the inactivation of the catecholamine neurotransmitters. The link between COMT activity and depressive and anxiety disorders is known, as well as its involvement in the associated biochemical processes. | D22S944 | nP = 693 (613 PD patients from 70 multiplex families, 83 child-parent triads). Caucasian. | Microsatellite D22S944 shows strongest association with PD (p = 0.0001–0.0003). Association is present in female subsample (p = 0.003), male subsample lacks association. Haplotype rs4680:G, rs4633:C, D22S944 (various variants) is associated with PD (p = 0.0001). | [23] |

| rs4680 and rs3219151 (GABRA6), rs10847832 (TMEM132D) | nP = 189 (105 males, 84 females)), nC = 398 (208 males, 190 females). Japan. | Allele rs4680:G and genotype rs4680:GG are associated with PD (p = 5.16 × 10−4 and p = 8.23 × 10−6 respectively). The male subsample lacks this association. A total of 5 SNPs were studied. See also GABRA6 and TMEM132D. | [24] | ||

| rs4680 | nP = 178 (91 male, 87 female), nC = 182 (90 male, 92 female). South Korea. | Genotype rs4680:AA increases risk of PD if compared to sum of other genotypes (p = 0.042). | [25] | ||

| rs4680 | nP = 51 (26 men, 25 women), nC = 45 (23 men, 22 women). South Korea. | Genotype rs4680:AA is associated with PD and increases anxiety (p = 0.01). | [26] | ||

| rs4680 | (1) 121 nuclear family. Canada. (2) nP = 89 (59 females, 30 males), nC = 89. Canada. | Allele rs4680:G is associated with PD in both samples (p = 0.005). In sample 2 association is stronger in female subsample (p = 0.008) while males show no association. In subsample of patients with PD with agoraphobia (nP = 68) allele rs4680:G is associated with disease (p = 0.01). TDT-test (transmission disequilibrium test) of the 1 sample showed an association of rs4680:G with PD as well (p = 0.005). No associations with rs165599 or rs737865. | [27] | ||

| rs4680 | nP = 2242. Germany. | Emotional abuse during childhood contributes to the development of PR in men with rs4680:GG genotypes and in women with rs4680: GG and rs4680: GA genotypes (p < 0.001 for all cases). | [28] | ||

| rs4680, rs165599 | nP = 589 (239 female, 350 male), nC = 539 (196 female, 343 male). USA. | Haplotype rs4680:G + rs165599:A is less frequent in patients of female subsample (p = 1.97 × 10−5). A total of 10 SNPs studied. | [29] | ||

| rs4680 | nP = 105 (66 female, 39 male), nC = 130 (89 female, 41 male). Turkey. | Allele rs4680:A is more frequent in patients (p = 0.017). SNP rs6313 (5HTR2A) was also studied, no association found. | [30] | ||

| rs4680 | nP = 115 (41 males, 74 females), nC = 115 (41 males, 74 females), Germany. | Active allele (472G = V158) is associated with PD (p = 0.04), especially in female subsample (p = 0.01). Male subsample lacks association (p = 1). Interaction with MAOA VNTR polymorphism was also studied, no association found. | [31] | ||

| CRHR1 (corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1) | Corticotropin releasing hormone receptors may be found in the limbic system and in the anterior pituitary gland, which are responsible for human behavior. It is may activate stress- and anxiety-related hormone release. | rs878886 and rs28632197 (AVPR1B) | (1) nP = 186 (128 female, 58 male), nC = 299 (217 female, 82 male). Germany. (2) nP = 173 (68 male, 105 female), nC = 495 (195 male, 300 female). Germany. | Genotype-allele pair rs28632197:TT (AVPR1B) + rs878886:G (CRHR1) shows strongest association with PD (p = 0.00057). 15 more associations below the significance threshold found. See also AVPR1B. | [15] |

| rs17689918 | nC = 239 (143 female), nP = 239 (143 female). Germany. nC = 292 (216 female), nP = 292 (216 female). Germany. | SNP rs17689918 is the only significant association with PD which survived all tests in the female subsample (p = 0.022). A total of 9 SNPs studied. | [32] | ||

| DBI (diazepam binding inhibitor) | DBI protein may be found in neuronal and glial cells of the central nervous system. It may be involved in PD via neuroactive steroid synthesis and modulation of GABA channel gating. | rs8192506 | nP = 126 (38 male, 88 female), nC = 229 (63 male, 166 female). Germany. | Rare allele rs8192506:G is found to be protective and almost three times more frequent in controls (p = 0.032). | [33] |

| DRD1 (dopamine D1 receptor) | DRD1 is known to be linked with depression and anxiety. | −800T-C, −94G-A, −48G-A and 45C > T, 1270C > G (CCK), rs6313, 1438A-G (5HTR2A) | nP = 127 (23 males, 104 females), nC = 146 (37 males, 109 females). Estonia. | SNP r −94G-A is associated with PD (p = 0.02). Haplotype CAA (−800T-C, −94G-A, −48G-A) is found to be protective (p = 0.03). A total of 90 SNPs were studied. See also CCK and 5HTR2A. | [18] |

| FOXP3 (forkhead- box protein P3 gene) | FOXP3 hypermethylation may potentially reflect impaired thymus and immunosuppressive Treg function. | Hypermethylation of the FOXP3 promoter region | nP = 131 (female = 85, male = 44), nC = 131 (female = 85, male = 44). Germany. | Epigenetic study. Lower hypermethylation of the FOXP3 promoter region is found in female PD patient subsample compared to control (p = 0.005). The male subsample lacks this association. | [34] |

| GABRA6 (γ-aminobutyric acid receptor, α 6 subunit) | GABRA6 subunit is well known for its link to anxiety in mammals. It is the main inhibitor of neurotransmitters in the CNS which regulates several physiological and psychological processes such as anxiety and depression. | rs3219151 and rs4680 (COMT), rs10847832 (TMEM132D) | nP = 189 (105 males, 84 females)), nC = 398 (208 males, 190 females). Japan. | Allele rs3219151:T and genotype rs3219151:TT are associated with PD (p = 2.00 × 10−7, p = 2.18 × 10−6, respectively). Patients carrying genotype rs11060369:AA (TMEM132D), and allele rs3219151:T (GABRA6) had significantly stronger response to frightening image demonstration (both p < 0.01). A total of 5 SNPs were studied. See also COMT and TMEM132D. | [24] |

| GABRA5 (γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor alpha5 subunit) | The GABA-ergic system is inhibitory. GABA receptors are targets for benzodiazepines that are used for PD treatment. | rs35399885 and rs8024564, rs8025575 (GABRB3) | n = 1591 (992 samples from 120 multiplex families). Europe. | SNP rs35399885 is associated with PD (p = 0.05). A total of 10 SNPs in GABRA3 and GABRA5 were studied. See also GABRA3. | [35] |

| GABRB3 (γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor alpha3 subunit) | rs8024564, rs8025575 and rs35399885 (GABRA5) | n = 1591 (992 samples from 120 multiplex families). Europe. | SNPs rs8024564 and rs8025575 are associated with PD (p = 0.005, p = 0.02 respectively). A total of 10 SNPs in GABRB3 and GABRA5 studied. See also GABRA5. | [35] | |

| GAD1 (glutamate decarboxylase 1) | Glutamate decarboxylase 1 is a key enzyme for the synthesis of the inhibitory and anxiolytic neurotransmitter GABA. Suspected of affecting mood and various mental disorders, including anxiety disorders and PD. | CpG hypermethylation | nP = 65 (female = 44, male = 21), nC = 65 (female = 44, male = 21). Germany. | Epigenetic study. GAD1 methylation levels are lower in patients (p = 0.001). Negative life events correlated with a decreased mean methylation in patients—the correlation was observed mainly in the female subsample (p = 0.01). A total of 38 methylation sites in promotor/2 intron of GAD1 and 10 promoter sites in GAD2 were studied. | [36] |

| rs3749034 | nP = 478 (female 286, male 192), nC = 584 (female 432, male 152). Germany. | Only rs3749034:A × gender remained significant in a combined sample (p = 0.045), but not in the replication sample. A total of 13 SNPs studied. | [37] | ||

| GHRL (ghrelin and obestatin prepropeptide) | Ghrelin is well-known for its anxiogenic and anxiolytic effects in rodents. Obestatin in contrast, decreases anxiety-like behavior in rodents. | rs4684677 | nP = 215 (63 male, 152 female), nC = 451 (199 male, 252 female). Sweden. | Allele rs4684677:A is associated with PD (p = 0.025). Two other studied SNPs showed no association. | [38] |

| GLO1 (glyoxalase I) | GLO1 gene expression is known to correlate with anxiety-like behavior in rodents. | rs2736654 | nP = 162 (64 male, 98 female), nC = 288 (119 male, 169 female). Italy. | Allele rs2736654:A (Glu) is associated with PD in a subsample of patients without agoraphobia (p < 0.025). No associations in the combined sample. | [39] |

| HCRTR2 (hypocretin receptor 2) | Hypocretin receptor 2 is expressed exclusively in the brain. Its agonist orexin-A may have an anxiogenic effect in rodents. It is also may be linked to PD via its role in respiration which seems to be altered in PD. | rs2653349 | nP = 215 (74 male, 141 female), nC = 454. Sweden. | Allele rs2653349:A is associated with PD in total sample and female subsample (p = 0.015, p = 0.0015 respectively). Other studied SNP rs2271933 (HCRTR1) showed no association. | [40] |

| HTR1A (5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A) | HTR1A is known to be associated with anxiety disorder and anxiogenic stimuli response. | rs4521432, rs6449693, rs6295, rs13361335 | nP = 107 (82 female, 25 male), nC = 125 (88 female, 37 male). Brazil. | Haplotype rs4521432:T, rs6449693:G, rs6295:G, rs13361335:T is associated with PD (p = 0.032). Only HTR1A showed association with PD (p = 0.027). 2 other genes (SLC6A4 and HTR2A) were also studied, no association found. | [41] |

| rs6295 | nP = 119 (43 male, 73 female), nC = 119 (43 male, 73 female). Japan. | Allele rs6295:G is associated with PD with agoraphobia (p = 0.047). | [42] | ||

| rs6295 | nP = 133 (49 males, 84 females), nC = 134 (49 males, 85 females). Germany. | Allele rs6295:G is associated with PD with agoraphobia (p = 0.03). | [27] | ||

| HTR2A (5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2A) | HTR2A over- and under-expression is known in PD patients and thus may lead to PD. | 102T > C | nP = 63 (29 males, 34 females), nC = 100 (47 males, 53 females). Japan. | SNP 102T > C is associated with PD (p = 0.048). Among subsamples, only patients with agoraphobia showed association (nP = 33, p = 0.016). Polymorphisms in 3 receptor genes (HTR1A (294G > A), HTR2A (102T > C), HTR2C (23Cys > Ser)) were studied. | [43] |

| rs6313 (102T-C), −1438A-G and −45C > T, 1270C > G (CCK),−800T-C, −94G-A, −48G-A (DRD1) | nP = 127 (23 males, 104 females), nC = 146 (37 males, 109 females). Estonia. | 5HTR2A polymorphism rs6313:C (102T-C) is associated with pure PD (p = 0.01). Haplotype AT (–1438A-G, rs6313:C (102T-C)) is protective (p = 0.04). Total of 90 SNPs studied. See also CCK and DRD1. | [18] | ||

| IKBKE (inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B kinase subunit epsilon) | NF-kB protein complex regulates immune system-related genes. The immune system may be involved in the development of anxiety disorders. | rs1539243 | nP = 210, nC = 356. Estonia. | Allele rs1539243:T is associated with PD (p < 0.001). SNP rs1554286 (IL10) was also studied. | [44] |

| rs1953090, rs2297543 | nP = 190 (44 male, 146 female), nC = 371 (111 male, 260 female). Estonia. | SNPs rs1953090 and rs2297543 are associated with PD in male subsample (p = 0.0013, p = 0.0456 respectively). A total of 14 SNPs were studied. | [45] | ||

| MAOA (monoamine oxidase A) | MAOA is known for its role in behavior and mental disorders. It plays important role in the metabolism of neuroactive and vasoactive amines in the central nervous system and peripheral tissues. | CpG hypomethylation | nP = 65 (44 females; 21 males), nC = 65 (44 females, 21 males). Germany. | Epigenetic study. Hypomethylation in patients in the female subsample compared to controls (p ≤ 0.001). No differences in the male subsample, methylation at 39 out of 42 sites are generally weak or absent. A total of 42 methylation sites were studied. | [46] |

| CpG Hypomethylation | nP = 28, females, PD with agoraphobia, nC = 28, females. Europe. nP = 20, females, PD with agoraphobia, nC = 20, females. Europe. | Epigenetic study. Hypomethylation in patients compared to controls (p < 0.001). The severity of PR and the degree of methylation are inversely related in patients (p = 0.01). A total of 13 methylation sites were studied. | [47] | ||

| MBL2 (mannose-binding lectin 2) | MBL deficiency is the most common hereditary defect in the human innate immune system. It may increase the susceptibility for autoimmune states. PD may be associated with an inflammatory and autoimmune processes. | rs7096206 rs5030737 | nP = 1100 (Bipolar disorder = 1000, PD = 100), nC = 349. | Two-marker MBL2 YA-haplotype (rs7096206, rs5030737) is associated with PD (p = 0.0074). No single SNPs were associated with PD. A total of 7 SNPs in genes MBL2, MASP1, MASP2 were studied. | [48] |

| MIR22 (microRNA 22) | MicroRNAs are known to play role in functional differentiation of neurons and their interactions with possible gene-candidates for PD (including GABRA6, CCKBR, OMC, BDNF, HTR2C, MAOA, and RGS2). | rs6502892 and rs11763020 (MIR339) | (1) nP = 203 (151 women, 52 men), nC = 341 (140 women, 201 men). Spain. (2) nP = 321 (202 women, 119 men), nC = 642 (415 women, 227 men). Finland. (3) nP = 102 (87 women, 25 men), nC = 829 (391 women, 438 men). Estonia. | In Spanish sample: SNP (rs6502892 (p < 0.0002) is associated with PD. Associations in other samples lack significance. A total of 712 SNPs in MIR genes were studied. See also MIR339. | [49] |

| rs8076112, rs6502892 and rs4977831, rs2039391 (MIR491) | nP = 341 (183 female, 158 male), nC = 229 (128 female, 101 male). South Korea. | SNP rs8076112 is associated with PD (p = 0.013). Haplotype rs8076112:C, rs6502892:C is more frequent in patients (p = 0.019). ASI-R score is associated with rs6502892 in patients with agoraphobia (p = 0.05). See also MIR491. | [50] | ||

| MIR339 (microRNA 339) | rs11763020 and rs6502892 (MIR22) | (1) nP = 203 (151 women, 52 men), nC = 341 (140 women, 201 men). Spain. (2) nP = 321 (202 women, 119 men), nC = 642 (415 women, 227 men). Finland. (3) nP = 102 (87 women, 25 men), nC = 829 (391 women, 438 men). Estonia. | In Spanish sample: SNPs rs11763020 (p < 0.00008) is associated with PD. Associations in other samples lack significance. A total of 712 SNPs in MIR genes were studied. See also MIR22. | [49] | |

| MIR491 (microRNA 491) | rs4977831, rs2039391 and rs8076112, rs6502892 (MIR22) | nP = 341 (183 female, 158 male), nC = 229 (128 female, 101 male). South Korea. | SNPs rs4977831 (p = 0.008) and rs2039391 (p = 0.015) are associated with PD. Haplotypes: rs4977831:G, rs2039391:G (p = 0.014); rs4977831:A, rs2039391:A (p = 0.0002) are more frequent in patients. See also MIR22. | [50] | |

| NPS (neuropeptide S) | Neuropeptide S can produce behavioral arousal and anxiolytic-like effects in rodents. | rs990310 rs11018195 | (1) nP = 183, nC = 315. Spain. (2) nP = 316, nC = 1317. Finland. | SNPs rs990310 and rs11018195, are in linkage disequilibrium and are associated with PD with agoraphobia in Spanish and Finland samples (p = 0.021, p = 0.022 respectively for Spain; p = 0.082, p = 0.083 respectively for Finland. A total of 35 SNP in NPS and NPSR1 were studied. | [51] |

| NPSR1 (neuropeptide S receptor 1) | NPSR1 may be linked to signs associated with anxiety and is potentially associated with anxiety disorders via the formation of limbic activity associated with fear. | rs324981 | nP = 140 (89 females, 51 males), nC= 245. Japan. | Allele rs324981:T is associated with PD in male subsample (p = 0.09). | [52] |

| NTRK3 (Tropomyosin receptor kinase C) | NTRK3 expression change may alter synaptic plasticity leading to abnormal release rates of certain neurotransmitters and thus to altered arousal threshold. | PromII | nP = 59, nC = 86, Spain. | Allele of PromII in 5′UTR-region of NTRK3 is associated with PD (p = 0.02). Patients show a tendency to heterozygosity. 3 other SNPs (IN3, EX5, EX12) were studied, no association found. | [53] |

| PBR (peripheral benzodiazepine receptor) | PBR is closely associated with personality traits for anxiety tolerance. | 485G > A | nP = 91 (48 Males, 43 females), nC = 178 (90 Males, 88 females). Japan. | Allele G of SNP 485G > A frequencies differ in patients and controls (p = 0.014). | [54] |

| PDE4B (phosphodiesterase 4B) | PDE4B’s altered expression leads to the change in intracellular cAMP concentrations, which is known in several mental disorders. PDE4B is involved in dopamine-associated and stress-related behaviors. | rs10454453, rs6588190, rs502958, rs1040716 | nP = 231 (85 males, 146 females), nC = 407 (162 males, 245 females). Japan. | Allele rs10454453:C is associated with PD in female subsample (p = 0.042). Haplotype rs10454453:C, rs6588190:T, rs502958:T, rs1040716:A is associated with PD in complete sample and female subsample (p = 0.031). A total of 15 SNPs were studied. | [55] |

| rs1040716, rs502958, rs10454453 | nP = 94 (75 female and 19 male), nC = (192, 108 female, 84 male). Russia. | Haplotypes: rs1040716:A, T + rs10454453:A + rs502958:A and rs1040716:A, T + rs502958:A are found to be protective (p < 0.05). | [56] | ||

| PGR (progesterone receptor) | Progesterone receptors are present in most brain regions involved in the pathophysiology of panic disorder: brain stem, hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and raphe nuclei. | rs10895068, ALU insertion polymorphism in intron 7 (PROGINS) | nP = 72 (24 male, 48 female, 50 with agoraphobia), nC = 452 (253 women 199 men). Sweden. | Allele rs10895068:A is more frequent in patients (p = 0.01). Association is found in female subsample (p = 0.0009), male subsample lacks association. PROGINS insertion was also studied, no association found. | [57] |

| RGS2 (regulator of G protein signaling 2) | RGS2 protein regulates G protein signaling activity and modulates receptor signaling neurotransmitters involved in the pathogenesis of anxiety diseases. | rs10801153 | (1) nP = 239 (143 female, 96 male), nC = 239 (143 female, 96 male), Germany. (2) nP = 292 (216 female, 76 male), nC = 292 (216 female, 76 male), Germany. | Allele rs10801153:G is associated with PD in a combined and 2nd sample (p = 0.017 for the combined sample). 5 SNPs (rs16834831, rs16829458, rs1342809, rs1890397, rs4606) in RGS2 were also studied, no association found. | [58] |

| Dinucleotide repeats [(GT)12–18/(CT)4–5] in the 5′-regulatory region | nP = 87 (59 female, 20 male), nC = 87 (59 female, 20 male) Germany. nP = 124 (30 female, 43 male), nC = 124 (30 female, 43 male) Italy. | Association was found in German female subsample (p = 0.01), but not in Italian sample (p = 0.54). | [59] | ||

| SLC6A4 (solute carrier family 6 member 1, SERT) | The norepinephrine transporter is responsible for the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine into the presynaptic nerve endings. | rs2242446, rs11076111, rs747107, rs1532701, rs933555, rs16955584, rs36021 | nP = 449 (321 female, 128 male), nC = 279 (223 female, 56 male). Denmark, Germany. | 7 SNPs are associated with PD with p-value from 0.0016 to 0.0499 in female subsample and patients with PD with agoraphobia (n = 226) subsample. Strongest associations are with rs2242446 (p = 0.0018) and rs747107 (p = 0.0016). Haplotype rs2242446, rs8052022 is associated with PD (p = 0.0022): rs2242446:T, rs8052022:T variant is protective, rs2242446:C, rs8052022:T is risk. The male subsample lacks association. A total of 29 SNPs were studied. | [60] |

| TPH2 (tryptophan hydroxylase) | TPH2 encodes key enzyme limiting the rate of transmission of nerve impulses. It is also involved in serotonin synthesis. | rs4570625 | nP = 108 (58 males, 50 females), nC = 247 (125 males, 122 females). South Korea. | Allele rs4570625:T is less frequent in patients and is very frequent in female controls (p = 0.016). | [61] |

| rs1386483 | nP = 213 (163 females, 50 males), nC = 303 (212 females, 91 male). Estonia. | SNP rs1386483 is associated with PD in female with pure PD phenotype (without comorbidity) subsample (p = 0.01). | [18] | ||

| TMEM132D (transmembrane protein 132D) | Transmembrane protein 132D is associated with the severity of anxiety symptoms in psychiatric patients. A gene may be involved in anxiety (anxiety-related behavior). | rs4759997 | (1) HLA-DRB1*13:02-positive subjects nP = 103; nC = 198. Japan. (2) HLA-DRB1*13:02-negative subjects nP = 438; nC = 1.341). Japan. | SNP rs4759997 is associated with PD in patients without the HLA-DRB1*13:02 allele (p = 5.02 × 10−6), but not in carriers of this allele. 9 SNPs with weaker associations were found. | [62] |

| rs900256, rs879560, rs10847832 | nP = 909, nC = 915 (three combined samples). Germany. | GWAS showed haplotype TA (rs7309727:T, rs11060369:A) association with PD. A replication study found several symptom severity associations, the strongest one with rs900256:C (p = 0.0003). Other risk alleles include rs879560:A (p = 0.0006) and rs10847832:A (p = 0.0007). | [63] | ||

| rs10847832 and rs4680 (COMT), rs3219151 (GABRA6) | nP = 189 (105 males, 84 females)), nC = 398 (208 males, 190 females). Japan. | Allele rs10847832:A is associated with PD (p = 0.03). Patients carrying genotype rs11060369:AA (TMEM132D), and allele rs3219151:T (GABRA6) had significantly stronger response to frightening image demonstration (both p < 0.01). A total of 5 SNPs were studied. See also COMT and GABRA6. | [24] | ||

| rs7309727, rs11060369 | nP = 1670, nC = 2266: (1) nP = 102, controls nC = 511. Aarhus. nP = 141, nC = 345. Copenhagen. nP = 217. Gothenburg. Denmark and Sweden. (2) nP = 217, nC = 285. Estonia. (3) nP = 38, nC = 40. Iowa. nP = 127, nC = 123. Toronto. USA/Canada. (4) nP = 77, nC = 192. USA. (5) nP = 760, nC = 760. Japan. | Five patient samples were studied. In the combined sample: Allele rs7309727:C is found to be risk (p = 1.1 × 10−8). Haplotype rs7309727:C, rs11060369:C is found to be risk (p = 1.4 × 10−8). No significance in the Japanese sample. A total of 4 SNPs were studied. | [64] |

| Gene Name 1 | Marker 2 | Sample 3 | Commentary 4 | Reference 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE (angiotensin I converting enzyme) | rs4646994 | nP = 101 (37 males, 64 female), nC = 184 (74 males, 110 females). Japan. | No significant associations were found. | [65] |

| rs4646994 | nP = 123 (81 female, 42 male), nC = 168 (104 female, 64 male). Turkey. | No significant associations were found. Ins allele is more frequent in male PD subsample but does not reach the significance threshold. | [66] | |

| ADORA2A (adenosine A2a receptor) | rs5751876 | nP = 104 (43 male, 61 female), nC = 192 (88 male, 104 female). China. | No significant associations were found. | [67] |

| rs1003774, rs743363, rs7678, rs1041749, SNP-4 C/T 78419 | nP = 153 (70 probands from families with PD, 83 child–parent ‘trios’. USA. | No association with single SNPs. Haplotype (rs1003774, SNP-4 C/T 78419, rs1041749) was closest to significance. | [68] | |

| ASIC1 (acid-sensing ion channel subunit 1, ACCN2) | D17S1294–D17S1293, rs8066566, rs16589, rs16585, rs12451625, rs4289044, rs8070997, rs9915774 | nP = 13, nC = 43. Faroe Islands, Denmark. nP = 243, nC = 645. Denmark. | A total of 38 SNPs were studied. All SNPs were first analyzed by GWAS in a Faroese sample. Several genotypes showed and a D17S1294–D17S1293 segment showed an association that did not survive further testing. Danish sample showed a nominally significant association with rs9915774 (p = 0.031) which didn’t survive Bonferroni correction. | [69] |

| BDNF (brain derived neurotrophic factor) | rs6265 | nP = 109 (39 males, 70 female), nC = 178 (75 males, 103 females). Japan. | No significant associations were found. | [70] |

| CAMKK2 (calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2) | rs3817190 | nP = 179, nC = 462. Germany. | A total of three genes were studied (P2RX7, P2RX4, and CAMKK2). No significant associations were found. However, patients with rs3817190:AA in CAMKK2 show more severe panic attacks and more distinguished agoraphobia. See also P2RX7. Patients with rs1718119:AA in P2RX7 show more severe symptoms of PD with agoraphobia as well. | [71] |

| CCK (cholecystokinin) | −36C- > T in CCK promoter | nP = 98, nC = 247. Japan. | No significant associations were found. | [72] |

| CCKBR (cholecystokinin B receptor) | microsatellite CT repeat in the CCKBR | nP = 71 (39 males, 32 females), nC = 199 (111 males 88 females), Japan. | No significant associations were found. | [73] |

| CHRNA4 (cholinergic receptor nicotinic α 4 subunit) | 3 SNPs | n = 88 (31 males, 57 females), Germany. | No significant associations were found. | [74] |

| COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) | rs165599, rs737865 | (1) 121 nuclear family. Canada. (2) nP = 89 (59 females, 30 males), nC = 89. Canada. | No significant associations were found. | [27] |

| rs4680 | nP = 26, nC = 26. South Korea. | No significant associations were found. | [75] | |

| DRD2 (dopamine receptor D2) | 141C ins/del polymorphism, rs1799732, rs12364283, rs1800497 | nP = 99 (76% females), nC = 104 (77% females). Poland. | No significant associations were found. | [76] |

| ELN (elastin) | Single-Stranded Conformational Polymorphism | 23 independent probands. USA. | No significant associations were found. | [77] |

| GABRA1 | Repeat polymorphisms in γ-aminobutyric acid receptor genes | 1) 21 multiplex panic disorder pedigrees. cP = 252 (107 male, 145 female). The Midwestern United States. 2) 5 multiplex panic disorder pedigrees. cP = 125. Iceland. | A total of 8 genes (GABRA1, GABRA2, GABRA3, GABRA4, GABRA5, GABRB1, GABRB3, GABRG2) were studied. No significant associations were found. | [78] |

| GABRA2 | ||||

| GABRA3 | ||||

| GABRA4 | ||||

| GABRA5 | ||||

| GABRB1 | ||||

| GABRB3 | ||||

| GABRG2 | ||||

| HTR1A (serotonin 1A receptor) | C(−1019)G | nP = 94 (52 male, 42 female), nC = 111 (52 male, 59 female). South Korea | No significant associations were found. | [79] |

| rs6295 | nP = 194, nC = 172. South Korea. | No significant associations were found. | [80] | |

| HTR2A (5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2A) | 1438A/G, rs6313 | nP = 107, nC = 161. South Korea. | No significant associations were found. The authors suggest further studies of 1438:G and rs6313:C (102:C) alleles which may be associated with symptom severity. | [81] |

| rs6313 | nP = 105 (66 female, 39 male), nC = 130 (89 female, 41 male). Turkey. | No significant associations were found. | [30] | |

| T102C | nP = 35, nC = 87. Germany. | No significant associations were found. | [82] | |

| T102C | (1) PD: nP = 94, nC = 94. Canada. (2) PD: nP = 86, nC = 86. Germany. (3) PD with agoraphobia: nP = 74, nC = 74. Canada. (4) PD with agoraphobia: nP = 59, nC = 59. Germany. | No significant associations were found. | [27] | |

| rs2296972 | nP = 154 (68.6% females), nC = 347 (70.8% females) | No association with PD diagnosis. A number of rs2296972:T alleles are associated with the severity of PD (p = 0.029). A total of 15 SNPs were studied. | [83] | |

| IKBKE (inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B kinase subunit epsilon) | rs1539243, rs1953090, rs3748022, rs15672 | nP = 190 (44 male, 146 female), nC = 371 (111 male, 260 female). Estonia. | No significant associations were found. Associations with rs1539243:T, rs1953090:C, and rs11117909:A alleles lose significance after correction for multiple testing. Associations with risk haplotype rs1539243:T, rs1953090:A, and haplotype rs1539243:C, rs1953090:C loses significance after multiple testing as well. | [45] |

| IL10 (interleukin 10) | rs1554286 | nP = 210, nC = 356. Estonia. | Allele rs1554286:C (IL10) is associated with a combined patient sample with MDD and PD. Association lost significance after the permutation test. | [44] |

| rs1800896 | nP = 135 (71 male, 64 female), nC = 135 (54 male, 81 female). South Korea. | No significant associations were found. However, rs180089:G is more frequent in the control group for females. | [84] | |

| LSAMP (limbic system associated membrane protein) | rs1461131, rs4831089, rs9874470, rs16824691 | nP = 196 (46 male, 150 female), nC = 364 (112 male, 252 female). Estonia. | Alleles rs1461131:A and rs4831089:A are associated with PD, but lose significance after correction for multiple testing. Haplotype rs9874470:T, rs4831089:A, rs16824691:T, rs1461131:A is protective, but loses significance after permutation tests. Authors suggest additional tests for these polymorphisms. | [85] |

| MAOA (monoamine oxidase A) | T941G | nP = 38 (PD = 38 (female = 21, male = 17), MD = 108 (female = 80, male = 28)), nC = 276 (female = 132, male = 144). Germany. | No significant associations were found. In the male subsample, 84.6% of patients carried the MAOA 941T allele. This result never reached the significance threshold due to the small sample size. | [86] |

| P2RX7 (purinergic receptor P2X 7) | rs1718119 | nP = 179, nC = 462. Germany. | A total of three genes studied (P2RX7, P2RX4, and CAMKK2). No significant associations found. However, patients with rs1718119:AA in P2RX7 show more severe symptoms of PD with agoraphobia. | [71] |

| RGS2 (regulator of G protein signaling 2) | rs2746071, rs2746072, rs12566194, rs4606, rs3767488 | nP = 186 (94 males and 92 females), nC = 380 (164 males, 216 females). Japan. | No significant associations found. Haplotype AC: rs2746071-rs2746072 was nominally associated and lost significance after tests. | [87] |

| SLC6A4 (solute carrier family 6 member 4) | 5-HTTLPR S/L (short/long) 44bp insertion/deletion | nP = 244 (143 male, 101 female), nC = 227 (102 male, 125 female). South Korea. | No significant associations found. | [88] |

| (1) nP = 88. Germany. (2) nP = 73. Italy. Matched control. | No significant associations found. | [89] | ||

| nP = 95 (53 female, 42 male). Italy. | The authors tested the hypothesis that the heterogeneity of CO2 reactivity in patients with PD and its possible relation to 5-HTT promoter polymorphism. No association found. | [90] | ||

| nP = 67 (53 female, 14 male). Brazil. | No significant associations found. Asymptomatic patients with panic disorder. No association on the MMPI scales between different genotype classifications and allele analyses. | [91] | ||

| nP = 194, nC = 172. South Korea. | No significant associations found. However, the number of separation life events and their interaction with 5-HTTLPR showed a statistically significant effect on PD. | [80] | ||

| TPH2 (tryptophan hydroxylase 2) | rs1800532 | nP = 244 (143 male, 101 female), nC = 227 (102 male, 125 female). South Korea. | No significant associations found. | [88] |

| 218 A/C | nP = 107, nC = 161. South Korea. | No significant associations found. | [81] | |

| rs4570625 rs4565946 | nP = 134, nC = 134. Germany. | No significant associations found. | [92] | |

| TPH (tryptophan hydroxylase) | A218C | nP = 35, nC = 87. Germany. | No significant associations found. | [82] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tretiakov, A.; Malakhova, A.; Naumova, E.; Rudko, O.; Klimov, E. Genetic Biomarkers of Panic Disorder: A Systematic Review. Genes 2020, 11, 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11111310

Tretiakov A, Malakhova A, Naumova E, Rudko O, Klimov E. Genetic Biomarkers of Panic Disorder: A Systematic Review. Genes. 2020; 11(11):1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11111310

Chicago/Turabian StyleTretiakov, Artemii, Alena Malakhova, Elena Naumova, Olga Rudko, and Eugene Klimov. 2020. "Genetic Biomarkers of Panic Disorder: A Systematic Review" Genes 11, no. 11: 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11111310

APA StyleTretiakov, A., Malakhova, A., Naumova, E., Rudko, O., & Klimov, E. (2020). Genetic Biomarkers of Panic Disorder: A Systematic Review. Genes, 11(11), 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11111310