Manipulation of Alternative Splicing of IKZF1 Elicits Distinct Gene Regulatory Responses in T Cells

Highlights

- Alternative splicing of IKZF1 in human T cells strongly influences gene expression, chromatin accessibility, and protein production.

- Even modest perturbations of IKZF1 splicing elicit compensatory responses in other IKAROS family members and impact autoimmunity-associated genes.

- Alternative transcripts generated by splicing are not simply transcriptional “noise,” but have clear functional roles in mature T cells.

- Dysregulation of IKZF1 splicing may contribute to autoimmune disease risk, highlighting splicing isoforms as potential therapeutic targets.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Resource Availability

2.2. Experimental Model and Subject Details

Gene Editing and Clone Selection

2.3. Laboratory Method Details

2.3.1. RNA Extraction and Library Preparation

2.3.2. Nuclei and ATAC-Seq Library Preparation

2.4. Immunoblotting

2.5. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. RNA Sequencing and Read Processing

2.5.2. Quantification of Gene Expression

2.5.3. ATAC-Seq Read Processing and Peak Calling

2.5.4. Primary T Lymphocytes

2.6. Differential Expression and Accessibility Analysis

2.7. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

3. Results

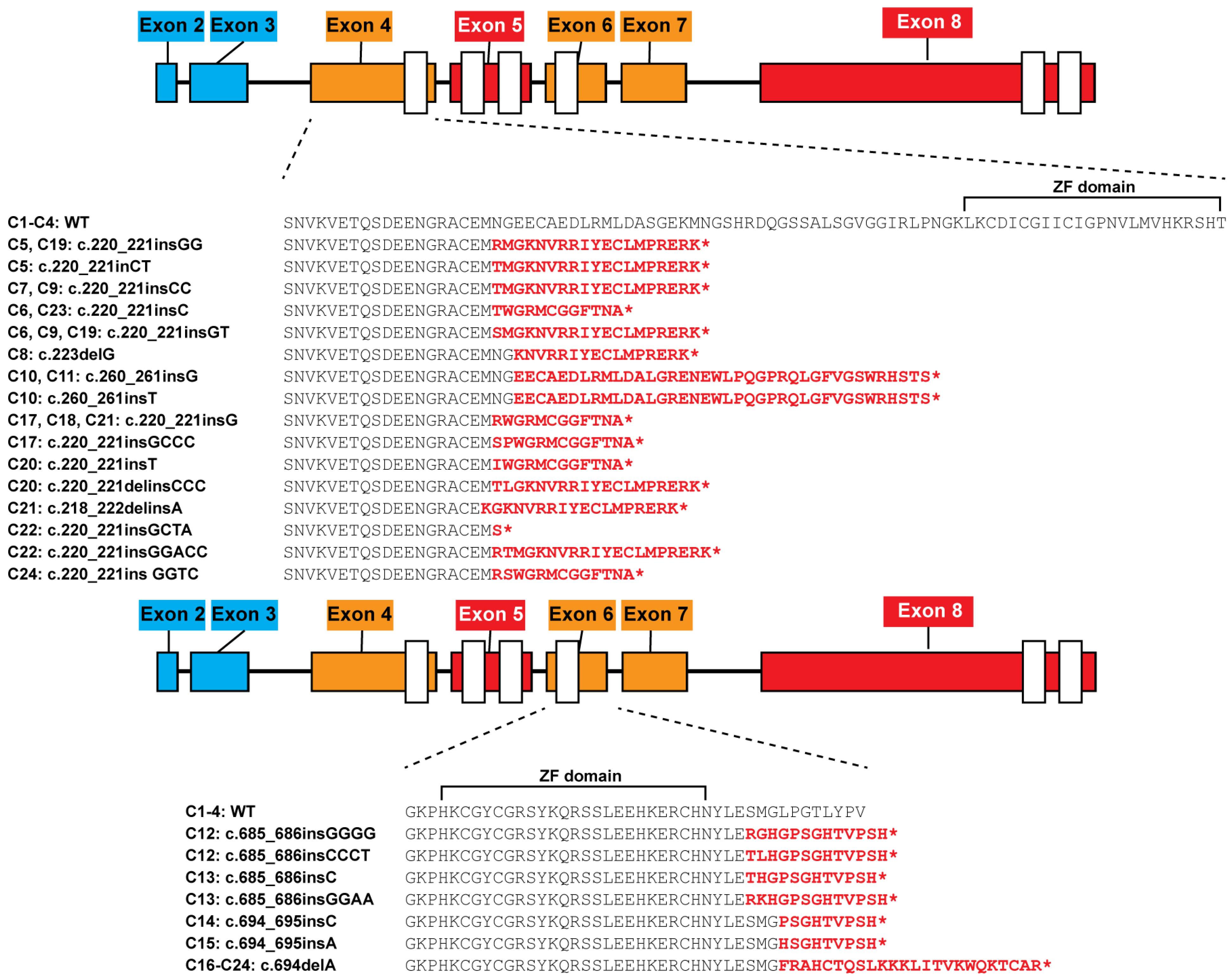

3.1. Targeting Frameshift Mutations to Alternatively Spliced IKZF1 Exons

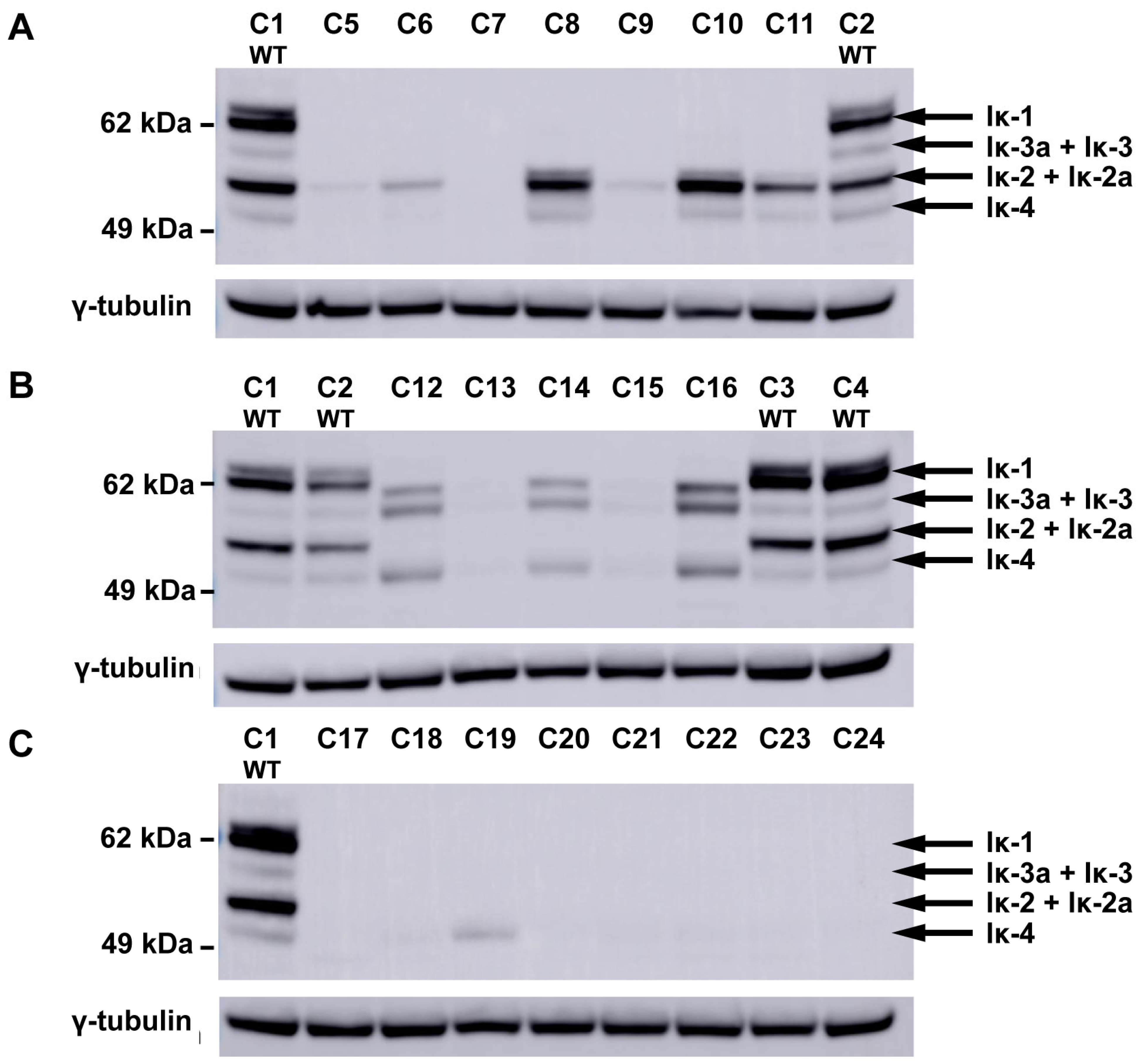

3.2. Mutations in Alternatively Spliced IKZF1 Exons Alter IKAROS Isoform Distribution

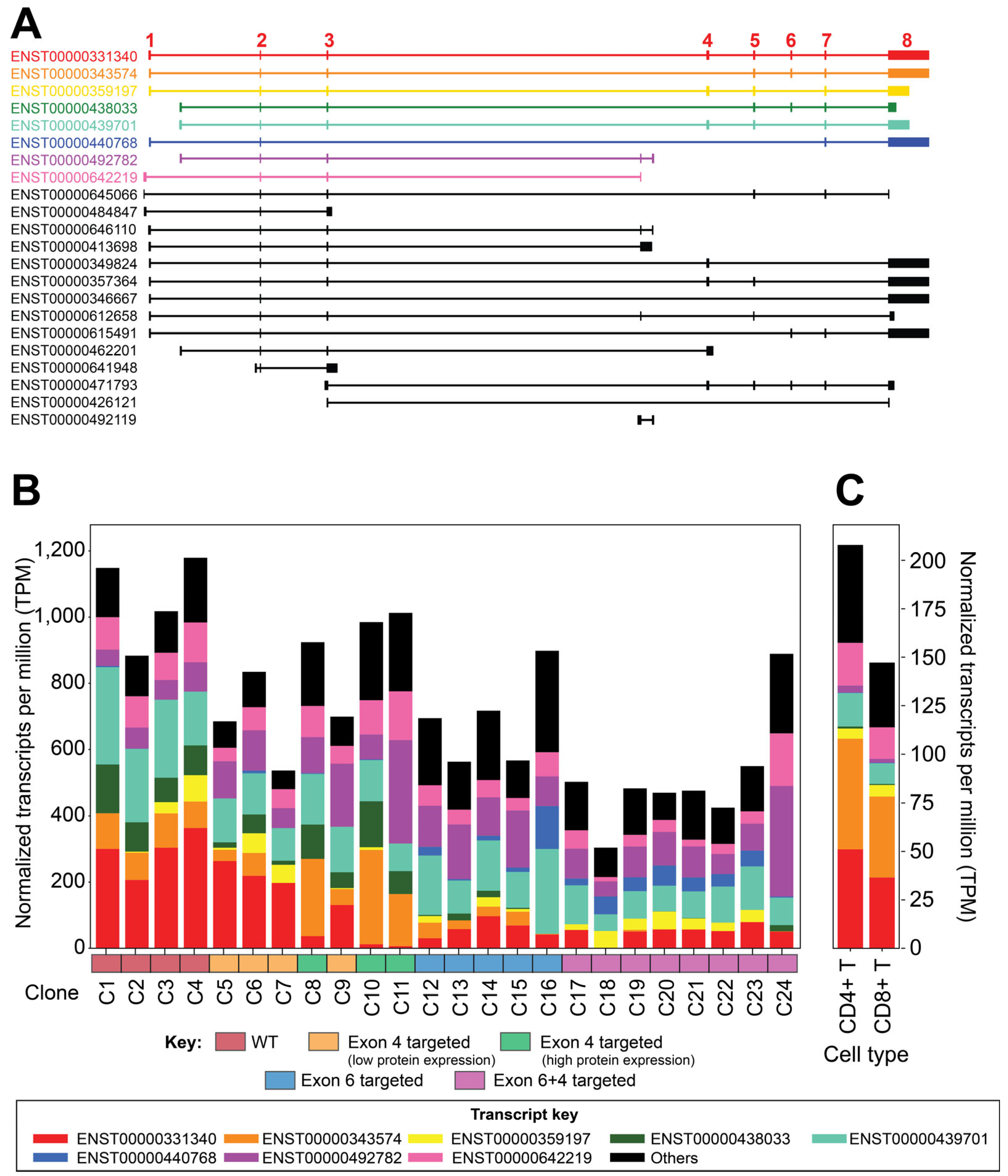

3.3. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Differences in IKZF1 Exon Usage After Gene-Targeting

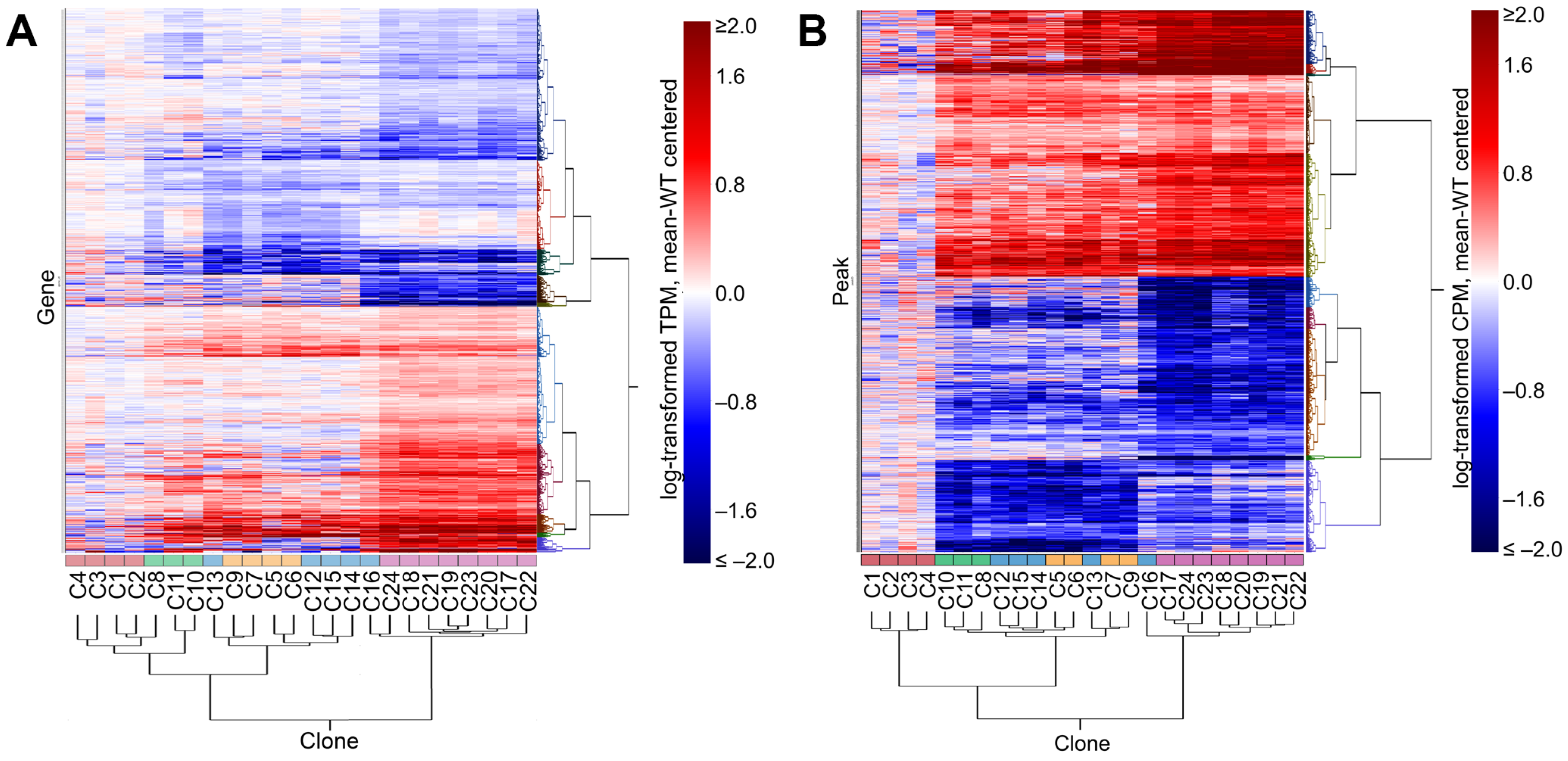

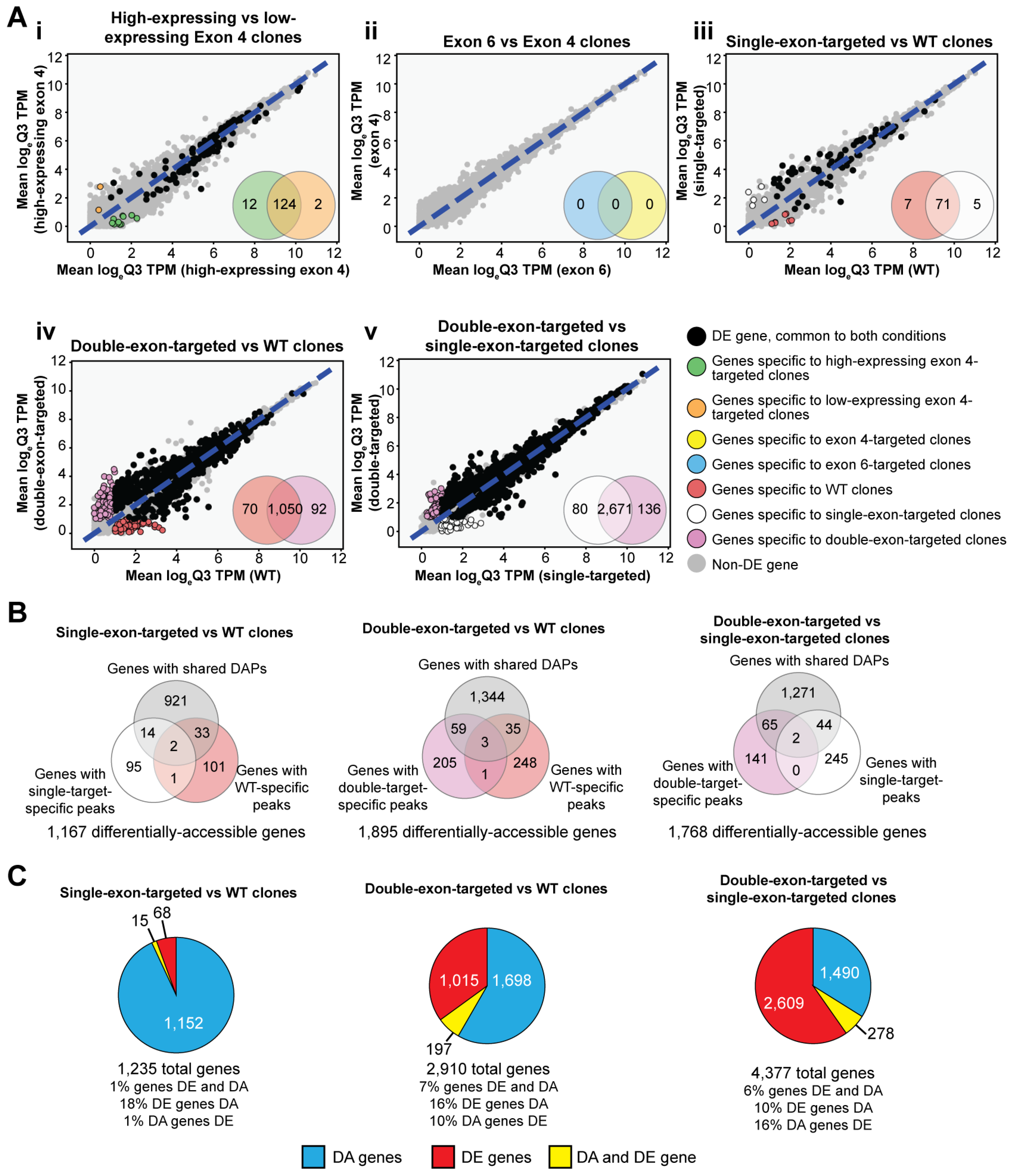

3.4. Perturbation of IKZF1 Splicing Affects Global Gene Expression and Chromatin Accessibility

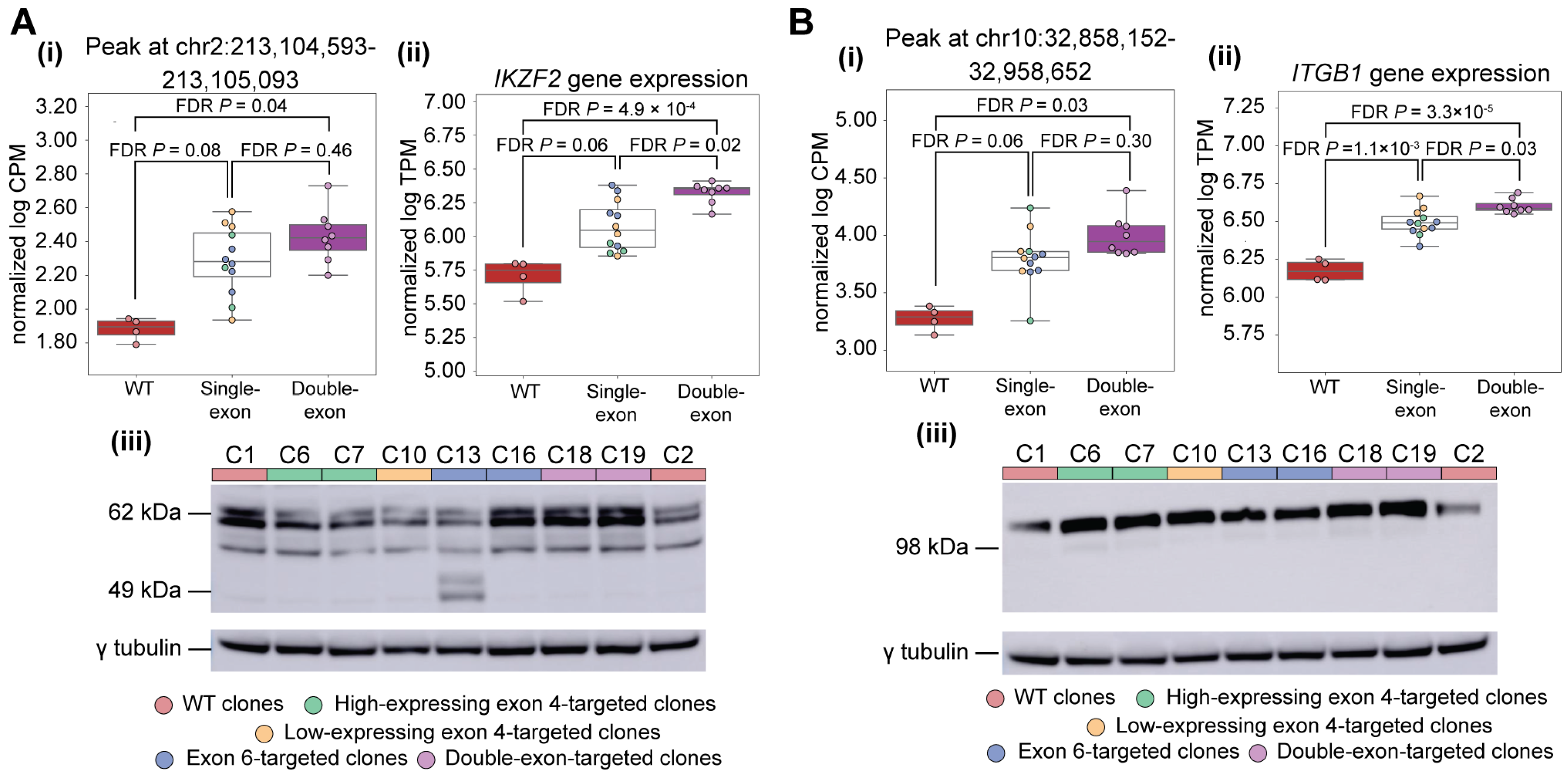

3.5. Perturbation of IKAROS Isoform Distribution Results in a Broad Response Affecting Multiple Immune-Associated Genes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deveson, I.W.; Brunck, M.E.; Blackburn, J.; Tseng, E.; Hon, T.; Clark, T.A.; Clark, M.B.; Crawford, J.; Dinger, M.E.; Nielsen, L.K.; et al. Universal Alternative Splicing of Noncoding Exons. Cell Syst. 2018, 6, 245–255.E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tress, M.L.; Abascal, F.; Valencia, A. Most Alternative Isoforms Are Not Functionally Important. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 408–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tress, M.L.; Abascal, F.; Valencia, A. Alternative Splicing May Not Be the Key to Proteome Complexity. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schjerven, H.; McLaughlin, J.; Arenzana, T.L.; Frietze, S.; Cheng, D.; Wadsworth, S.E.; Lawson, G.W.; Bensinger, S.J.; Farnham, P.J.; Witte, O.N.; et al. Selective regulation of lymphopoiesis and leukemogenesis by individual zinc fingers of Ikaros. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Nichogiannopoulou, A.; Wu, L.; Sun, L.; Sharpe, A.H.; Bigby, M.; Georgopoulos, K. Selective defects in the development of the fetal and adult lymphoid system in mice with an Ikaros null mutation. Immunity 1996, 5, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, K.; Winandy, S.; Avitahl, N. The role of the Ikaros gene in lymphocyte development and homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997, 15, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swafford, A.D.; Howson, J.M.; Davison, L.J.; Wallace, C.; Smyth, D.J.; Schuilenburg, H.; Maisuria-Armer, M.; Mistry, T.; Lenardo, M.J.; Todd, J.A. An allele of IKZF1 (Ikaros) conferring susceptibility to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia protects against type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2011, 60, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.C.; Clayton, D.G.; Concannon, P.; Akolkar, B.; Cooper, J.D.; Erlich, H.A.; Julier, C.; Morahan, G.; Nerup, J.; Nierras, C.; et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Chen, W.M.; Burren, O.; Cooper, N.J.; Quinlan, A.R.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Farber, E.; Bonnie, J.K.; Szpak, M.; Schofield, E.; et al. Fine mapping of type 1 diabetes susceptibility loci and evidence for colocalization of causal variants with lymphoid gene enhancers. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, S.G.; Vyse, T.J.; Cunninghame Graham, D.S. The genetics of lupus: A functional perspective. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ji, T.; Li, Y.; Yu, L. Multiple functions of Ikaros in hematological malignancies, solid tumor and autoimmune diseases. Gene 2019, 684, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westra, H.J.; Peters, M.J.; Esko, T.; Yaghootkar, H.; Schurmann, C.; Kettunen, J.; Christiansen, M.W.; Fairfax, B.P.; Schramm, K.; Powell, J.E.; et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Niu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Yang, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. IKZF1 polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility, cytokine levels, and clinical features in systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicine 2020, 99, e22607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Georgopoulos, K. Ikaros fingers on lymphocyte differentiation. Int. J. Hematol. 2014, 100, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnar, A.; Georgopoulos, K. The Ikaros gene encodes a family of functionally diverse zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 8292–8303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, K. The making of a lymphocyte: The choice among disparate cell fates and the IKAROS enigma. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, A.; Wu, P.; Largespada, D.A.; Vortkamp, A.; Scherer, S.; Copeland, N.G.; Jenkins, N.A.; Bruns, G.; Georgopoulos, K. The Ikaros gene encodes a family of lymphocyte-restricted zinc finger DNA binding proteins, highly conserved in human and mouse. J. Immunol. 1996, 156, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marke, R.; van Leeuwen, F.N.; Scheijen, B. The many faces of IKZF1 in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 2018, 103, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, B.; Payne, J.L.; Song, C.; Ge, Z.; Gowda, C.; Iyer, S.; Dhanyamraju, P.K.; Dorsam, G.; Reeves, M.E.; et al. Ikaros tumor suppressor function includes induction of active enhancers and super-enhancers along with pioneering activity. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2720–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrow, J.; Frankish, A.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Tapanari, E.; Diekhans, M.; Kokocinski, F.; Aken, B.L.; Barrell, D.; Zadissa, A.; Searle, S.; et al. GENCODE: The reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1760–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro, J.D.; Wu, B.; Litzenburger, U.M.; Ruff, D.; Gonzales, M.L.; Snyder, M.P.; Chang, H.Y.; Greenleaf, W.J. Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals principles of regulatory variation. Nature 2015, 523, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, J.R.B.; Concannon, P.; Tardaguila, M.; Conesa, A.; McIntyre, L.M. Event Analysis: Using Transcript Events To Improve Estimates of Abundance in RNA-seq Data. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2018, 8, 2923–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Trapnell, C.; Pop, M.; Salzberg, S.L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ruotti, V.; Stewart, R.M.; Thomson, J.A.; Dewey, C.N. RNA-Seq gene expression estimation with read mapping uncertainty. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.R.B.; Conesa, A.; Mika, M.; New, F.N.; Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Atkinson, M.A.; Rich, S.S.; McIntyre, L.M.; Concannon, P. Disease-specific biases in alternative splicing and tissue-specific dysregulation revealed by multitissue profiling of lymphocyte gene expression in type 1 diabetes. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, J.H.; Purdom, E.; Hansen, K.D.; Dudoit, S. Evaluation of statistical methods for normalization and differential expression in mRNA-Seq experiments. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillies, M.A.; Rau, A.; Aubert, J.; Hennequet-Antier, C.; Jeanmougin, M.; Servant, N.; Keime, C.; Marot, G.; Castel, D.; Estelle, J.; et al. A comprehensive evaluation of normalization methods for Illumina high-throughput RNA sequencing data analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 2013, 14, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P.; Corces, M.R.; Xu, J.; Reuter, V.P.; Chang, H.Y.; Sheffield, N.C. PEPATAC: An optimized pipeline for ATAC-seq data analysis with serial alignments. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2021, 3, lqab101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Lei, R.; Ding, S.W.; Zhu, S. Skewer: A fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, G.G.; Hall, I.M. SAMBLASTER: Fast duplicate marking and structural variant read extraction. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2503–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; Oshlack, A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.W.; Chen, Y.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinz, S.; Benner, C.; Spann, N.; Bertolino, E.; Lin, Y.C.; Laslo, P.; Cheng, J.X.; Murre, C.; Singh, H.; Glass, C.K. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, C.C.; Inshaw, J.R.J.; Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Chen, W.M.; Santa Cruz, D.F.; Yang, H.; Cutler, A.J.; Crouch, D.J.M.; Farber, E.; Bridges, S.L., Jr.; et al. Fine-mapping, trans-ancestral and genomic analyses identify causal variants, cells, genes and drug targets for type 1 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, J.; Geusz, R.J.; Okino, M.L.; Han, J.Y.; Miller, M.; Melton, R.; Beebe, E.; Benaglio, P.; Huang, S.; Korgaonkar, K.; et al. Interpreting type 1 diabetes risk with genetics and single-cell epigenomics. Nature 2021, 594, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliskan, M.; Brown, C.D.; Maranville, J.C. A catalog of GWAS fine-mapping efforts in autoimmune disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, R.; Fouodo, C.J.K.; Konig, I.R.; Busch, H.; Wohlers, I. A survey of genome-wide association studies, polygenic scores and UK Biobank highlights resources for autoimmune disease genetics. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 972107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, J.; Holmes, M.; Chong, B.; Crossley, M. Eos and pegasus, two members of the Ikaros family of proteins with distinct DNA binding activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 38347–38354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczyk, M.; Carracedo, S.; Gullberg, D. Integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 2010, 339, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, I.; Yoshida, T.; Jena, N.; Qi, X.; Zhang, J.; Van Etten, R.A.; Georgopoulos, K. Loss of Ikaros DNA-binding function confers integrin-dependent survival on pre-B cells and progression to acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.J.; Pastor, L.; Newman, J.R.B.; Concannon, P. Genetic Control of Splicing at SIRPG Modulates Risk of Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2022, 71, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, R.T.; Weiss, A. Jurkat T cells and development of the T-cell receptor signalling paradigm. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshino, A.; Okada, S.; Yoshida, K.; Nishida, N.; Okuno, Y.; Ueno, H.; Yamashita, M.; Okano, T.; Tsumura, M.; Nishimura, S.; et al. Abnormal hematopoiesis and autoimmunity in human subjects with germline IKZF1 mutations. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nieuwenhove, E.; Garcia-Perez, J.E.; Helsen, C.; Rodriguez, P.D.; van Schouwenburg, P.A.; Dooley, J.; Schlenner, S.; van der Burg, M.; Verhoeyen, E.; Gijsbers, R.; et al. A kindred with mutant IKAROS and autoimmunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 699–702.E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Quinlan, A.R.; Mackey, A.J.; Wright, J.A.; Buckner, J.H.; Habib, T.; Rich, S.S.; Concannon, P. Targeted Deep Sequencing in Multiple-Affected Sibships of European Ancestry Identifies Rare Deleterious Variants in PTPN22 That Confer Risk for Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2016, 65, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Buckner, J.H.; Concannon, P. A haplotype-based analysis of the PTPN22 locus in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2006, 55, 2883–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ge, Y.; Concannon, P. Molecular-genetic characterization of common, noncoding UBASH3A variants associated with type 1 diabetes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 26, 1060–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejentsev, S.; Walker, N.; Riches, D.; Egholm, M.; Todd, J.A. Rare variants of IFIH1, a gene implicated in antiviral responses, protect against type 1 diabetes. Science 2009, 324, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, H.; Howson, J.M.; Esposito, L.; Heward, J.; Snook, H.; Chamberlain, G.; Rainbow, D.B.; Hunter, K.M.; Smith, A.N.; Di Genova, G.; et al. Association of the T-cell regulatory gene CTLA4 with susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Nature 2003, 423, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.R.B.; Long, S.A.; Speake, C.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Cerosaletti, K.; Rich, S.S.; Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; McIntyre, L.M.; Buckner, J.H.; Concannon, P. Shifts in isoform usage underlie transcriptional differences in regulatory T cells in type 1 diabetes. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Syed, F.; Simpson, E.; Lee, C.C.; Liu, J.; Chang, G.; Dong, C.; Seitz, C.; Eizirik, D.L.; Mirmira, R.G.; et al. The Impact of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines on Alternative Splicing Patterns in Human Islets. Diabetes 2021, 71, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pastor, L.; Newman, J.R.B.; Callahan, C.M.; Pickin, R.R.; Atkinson, M.A.; Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Concannon, P. Manipulation of Alternative Splicing of IKZF1 Elicits Distinct Gene Regulatory Responses in T Cells. Cells 2026, 15, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030221

Pastor L, Newman JRB, Callahan CM, Pickin RR, Atkinson MA, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Concannon P. Manipulation of Alternative Splicing of IKZF1 Elicits Distinct Gene Regulatory Responses in T Cells. Cells. 2026; 15(3):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030221

Chicago/Turabian StylePastor, Lucia, Jeremy R. B. Newman, Colin M. Callahan, Rebecca R. Pickin, Mark A. Atkinson, Suna Onengut-Gumuscu, and Patrick Concannon. 2026. "Manipulation of Alternative Splicing of IKZF1 Elicits Distinct Gene Regulatory Responses in T Cells" Cells 15, no. 3: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030221

APA StylePastor, L., Newman, J. R. B., Callahan, C. M., Pickin, R. R., Atkinson, M. A., Onengut-Gumuscu, S., & Concannon, P. (2026). Manipulation of Alternative Splicing of IKZF1 Elicits Distinct Gene Regulatory Responses in T Cells. Cells, 15(3), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030221