The Microbiome–Neurodegeneration Interface: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Gut Microbiome Overview

3. The Gut Microbiota: Composition and Key Functions

3.1. The Vagus Nerve (VN) and Autonomic Nervous System (ANS)

3.2. ENS and Microbiota-Neuron Crosstalk

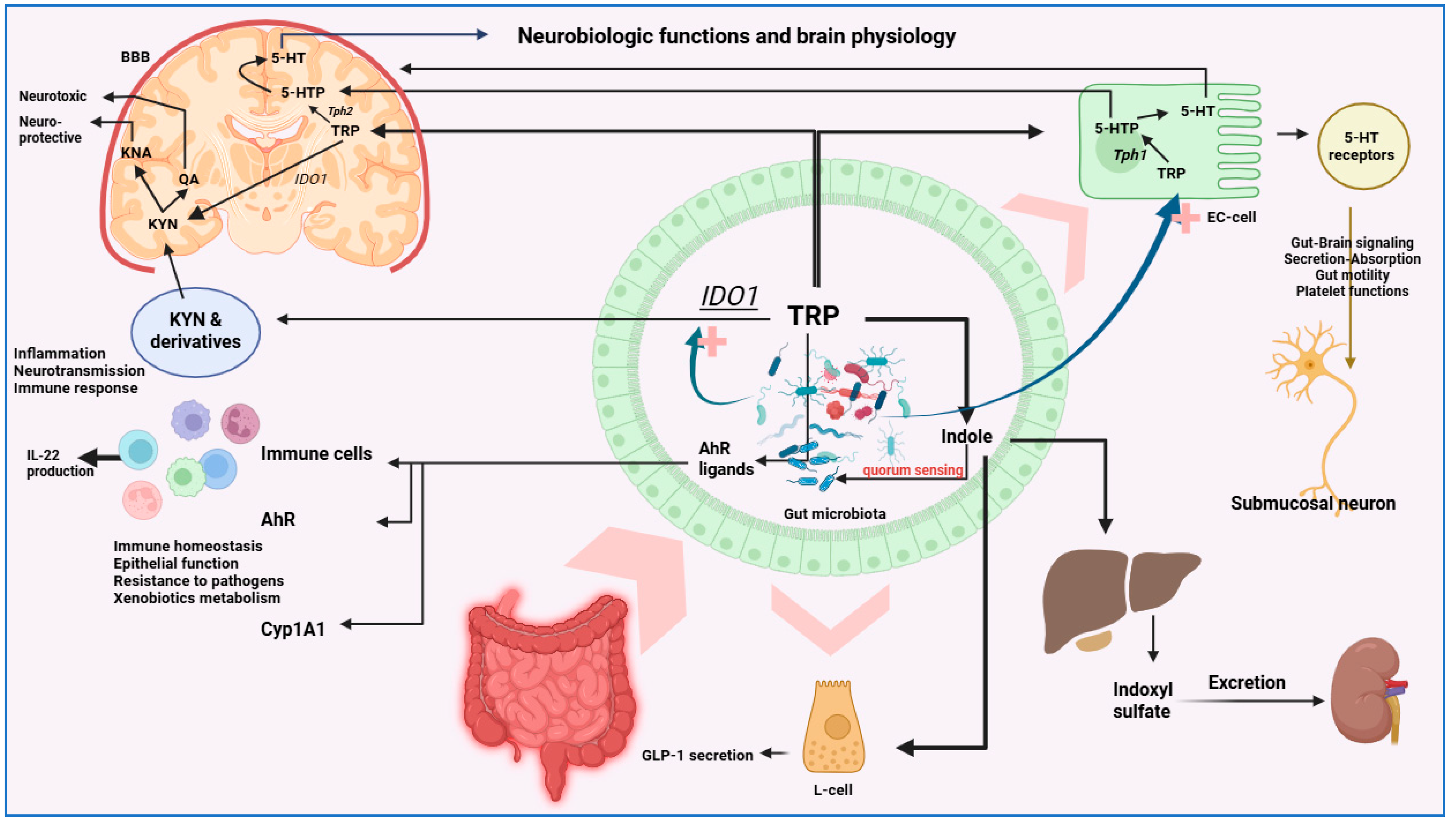

4. Pathways of Gut–Brain Communication

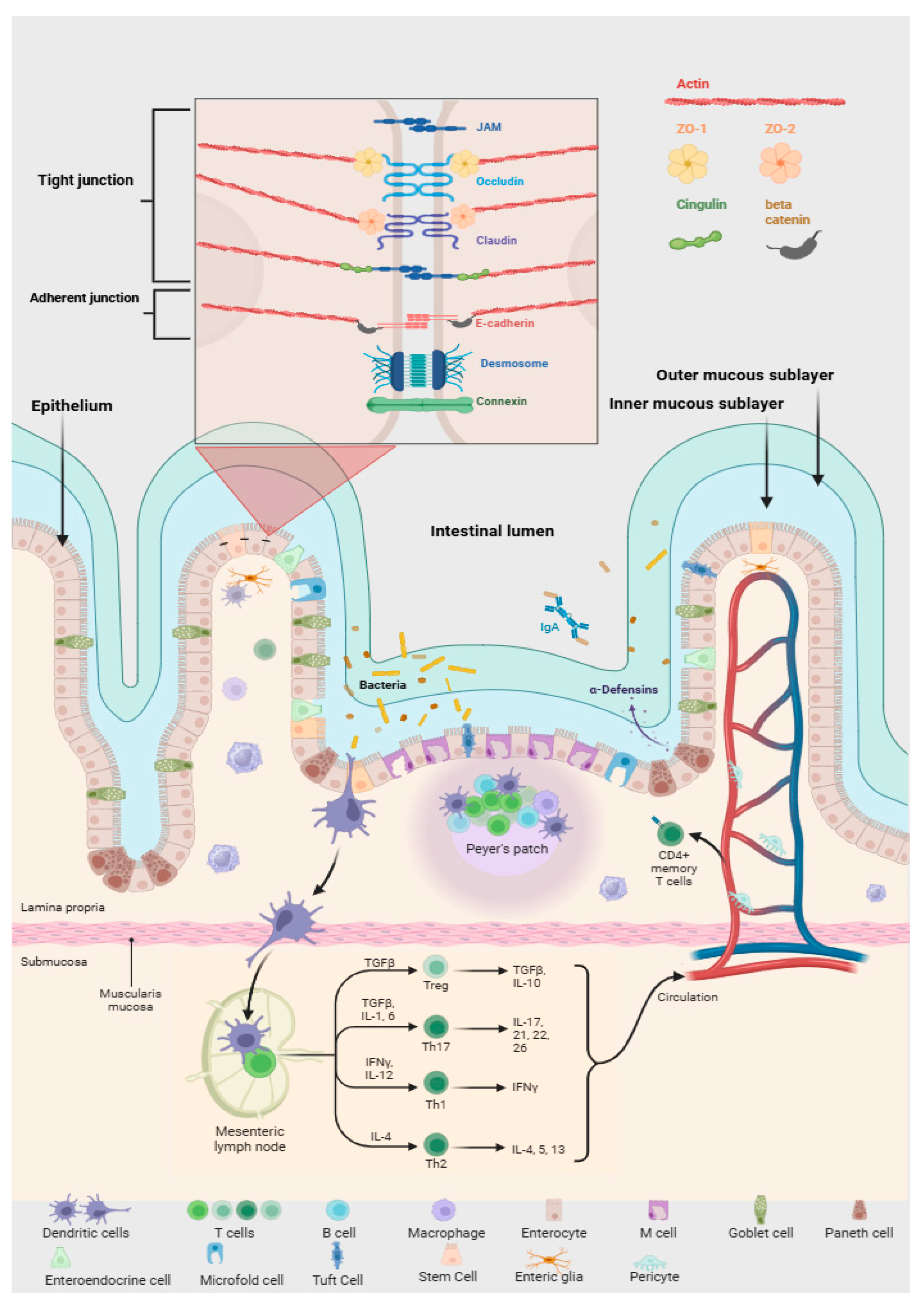

5. Gut Microbiota Brain Signaling and the Immune System

6. Neurotransmitters

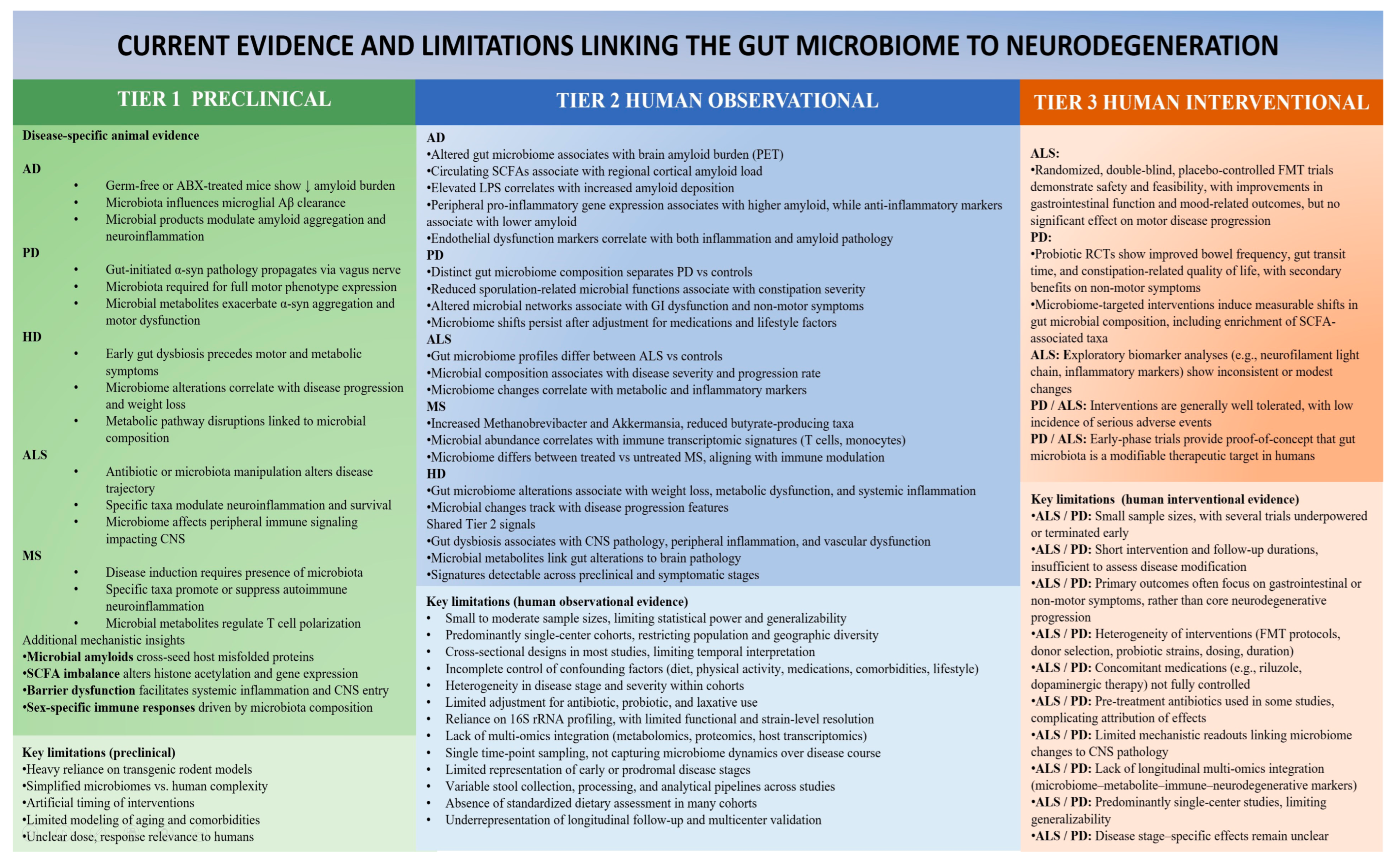

7. Evidence Linking the Microbiome to Neurodegeneration

8. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

9. Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

10. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

11. Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

12. Huntington Disease (HD)

13. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-HT | serotonin |

| 5-HTP | 5-hydroxytryptophan |

| 6-OHDA | 6-hydroxydopamine |

| α-SYN | α-synuclein |

| aMCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| AMPs | Antimicrobial peptides |

| ANS | Autonomic nervous system |

| AhR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| APP | amyloid precursor protein |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CH25H | Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| DMV | Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus |

| DRG | Dorsal root ganglia |

| ENS | Enteric nervous system |

| EAE | Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| FFAR2 | free fatty acid receptor 2 |

| FFAR3 | free fatty acid receptor 3 |

| FMT | Fecal microbiota transplantation |

| GALT | Gut-associated lymphoid tissue |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| GBA | Gut–brain-axis |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal reflux |

| GF | Germ free |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GIT | Gastrointestinal tract |

| Gi/o | inhibitory G protein alpha i/o family |

| Gq/11 | G protein alpha q/11 family |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| GPR43 | G protein-coupled receptor 43 |

| GPR41 | G protein-coupled receptor 41 |

| GPR109A | G protein-coupled receptor 109A |

| GVB | Gut vascular barrier |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| HCAR2 | hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 |

| HD | Huntington disease |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HMOs | Human milk oligosaccharides |

| HTT | Huntington gene |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| LBs | Lewy bodies |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| MAMPs | Microbe-associated molecular patterns |

| MGBA | Microbiota-gut–brain axis |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| MUC | Transmembrane mucin |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| NDs | Neurodegenerative diseases |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 |

| NTS | Nucleus tractus solitarius |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PFFs | Preformed fibrils |

| PGN | Peptidoglycan |

| PRRs | Pattern recognition receptors |

| PSEN1 | Presenilin 1 |

| PYY | peptide YY |

| QS | Quorum sensing |

| RgpA | Releases gingipain |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RRMS | Relapsing-remitting MS |

| RBD | REM sleep behavior disorder |

| SPMS | Secondary progressive MS |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| SIBO | Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

| SNpc | Substantia nigra pars compacta |

| SG | Sympathetic ganglia |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TFHs | T follicular helper cells |

| TJ | Tight junction |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| TPH1 | Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 |

| Treg | Impaired regulatory T cell |

| IFN-I | Type I interferon |

| VGLUT1 | Vesicular glutamate transporter 1 |

| VN | Vagus nerve |

| VNS | Vagus-nerve stimulation |

| ZO | zonula occluden |

References

- Nicholson, J.K.; Holmes, E.; Kinross, J.; Burcelin, R.; Gibson, G.; Jia, W.; Pettersson, S. Host-Gut Microbiota Metabolic Interactions. Science 2012, 336, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Wade, P.A. Crosstalk between the microbiome and epigenome: Messages from bugs. J. Biochem. 2018, 163, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, P.W.; Jeffery, I.B. Gut microbiota and aging. Science 2015, 350, 1214–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremlett, H.; Bauer, K.C.; Appel-Cresswell, S.; Finlay, B.B.; Waubant, E. The gut microbiome in human neurological disease: A review. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, A.; Aleya, L.; Kamel, M. Microbiota’s role in health and diseases. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 36967–36983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, C.C.; Cerovic, V. Interactions of the microbiota with the mucosal immune system. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 199, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Lehto, S.M.; Harty, S.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Burnet, P.W.J. Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria-Gut-Brain Signals. Trends Neurosci. 2016, 39, 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, B.T.; Yang, Z.; Luber, J.M.; Beaudin, M.; Wibowo, M.C.; Baek, C.; Mehlenbacher, E.; Patel, C.J.; Kostic, A.D. The Landscape of Genetic Content in the Gut and Oral Human Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 283–295.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, S.; Yeo, J.; Abubaker, S.; Hammami, R. Neuromicrobiology, an emerging neurometabolic facet of the gut microbiome? Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1098412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharon, G.; Cruz, N.J.; Kang, D.-W.; Gandal, M.J.; Wang, B.; Kim, Y.-M.; Zink, E.M.; Casey, C.P.; Taylor, B.C.; Lane, C.J.; et al. Human Gut Microbiota from Autism Spectrum Disorder Promote Behavioral Symptoms in Mice. Cell 2019, 177, 1600–1618.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falony, G.; Vandeputte, D.; Caenepeel, C.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Daryoush, T.; Vermeire, S.; Raes, J. The human microbiome in health and disease: Hype or hope. Acta Clin. Belg. 2019, 74, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wastyk, H.C.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Perelman, D.; Dahan, D.; Merrill, B.D.; Yu, F.B.; Topf, M.; Gonzalez, C.G.; Van Treuren, W.; Han, S.; et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell 2021, 184, 4137–4153.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosca, A.; Leclerc, M.; Hugot, J.P. Gut Microbiota Diversity and Human Diseases: Should We Reintroduce Key Predators in Our Ecosystem? Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, C.; Antonioli, L.; Colucci, R.; Blandizzi, C.; Fornai, M. Interplay among gut microbiota, intestinal mucosal barrier and enteric neuro-immune system: A common path to neurodegenerative diseases? Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Xing, C.; Long, W.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, R.F. Impact of microbiota on central nervous system and neurological diseases: The gut-brain axis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.-X.; Goh, W.-R.; Wu, R.-N.; Yue, X.-Q.; Luo, X.; Khine, W.W.T.; Wu, J.-R.; Lee, Y.-K. Revisit gut microbiota and its impact on human health and disease. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jia, H.; Cai, X.; Zhong, H.; Feng, Q.; Sunagawa, S.; Arumugam, M.; Kultima, J.R.; Prifti, E.; Nielsen, T.; et al. An integrated catalog of reference genes in the human gut microbiome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.M.; Ma, J.; Prince, A.L.; Antony, K.M.; Seferovic, M.D.; Aagaard, K.M. Maturation of the infant microbiome community structure and function across multiple body sites and in relation to mode of delivery. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R.C.; Manges, A.R.; Finlay, B.B.; Prendergast, A.J. The Human Microbiome and Child Growth—First 1000 Days and Beyond. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younge, N.E.; Araújo-Pérez, F.; Brandon, D.; Seed, P.C. Early-life skin microbiota in hospitalized preterm and full-term infants. Microbiome 2018, 6, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manos, J. The human microbiome in disease and pathology. APMIS 2022, 130, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Byrd, A.L.; Deming, C.; Conlan, S.; Kong, H.H.; Segre, J.A. Biogeography and individuality shape function in the human skin metagenome. Nature 2014, 514, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R.E.; Townsend, S.D. Temporal development of the infant gut microbiome. Open Biol. 2019, 9, 190128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, G.; Sampson, T.R.; Geschwind, D.H.; Mazmanian, S.K. The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome. Cell 2016, 167, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokela, R.; Ponsero, A.J.; Dikareva, E.; Wei, X.; Kolho, K.-L.; Korpela, K.; de Vos, W.M.; Salonen, A. Sources of gut microbiota variation in a large longitudinal Finnish infant cohort. eBioMedicine 2023, 94, 104695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez, H.; Nieto, P.A.; Mars, R.A.; Ghavami, M.; Sew Hoy, C.; Sukhum, K. Early life gut microbiome and its impact on childhood health and chronic conditions. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2463567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, C.S.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. Contribution of Gut Microbiota to Immune Tolerance in Infants. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 7823316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, E.M.M. Microbiota-Brain-Gut Axis and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2017, 17, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognini, P. Gut Microbiota: A Potential Regulator of Neurodevelopment. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambring, C.B.; Siraj, S.; Patel, K.; Sankpal, U.T.; Mathew, S.; Basha, R. Impact of the Microbiome on the Immune System. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 39, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Sandhu, K.; Peterson, V.; Dinan, T.G. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, E.R.; Sanders, J.G.; Song, S.J.; Amato, K.R.; Clark, A.G.; Knight, R. The human microbiome in evolution. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 46, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xie, G.; Liu, M.; Yuan, B.; Chai, H.; Wang, W.; Cheng, P. Implications of Gut Microbiota in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 785644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajeri, M.H.; Brummer, R.J.M.; Rastall, R.A.; Weersma, R.K.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faas, M.; Eggersdorfer, M. The role of the microbiome for human health: From basic science to clinical applications. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincic, A.M.; Antal, M.; Filip, L.; Miere, D. Modulation of gut microbiome in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1832–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, S.; Gisevius, B.; Duscha, A.; Haghikia, A. Implications of Diet and The Gut Microbiome in Neuroinflammatory and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, T.R.; Mazmanian, S.K. Control of Brain Development, Function, and Behavior by the Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, E.; Horváth-Puhó, E.; Thomsen, R.W.; Djurhuus, J.C.; Pedersen, L.; Borghammer, P.; Sørensen, H.T. Vagotomy and subsequent risk of Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2015, 78, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyte, M. Microbial Endocrinology and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. In Microbial Endocrinology: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease; Lyte, M., Cryan, J.F., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, E.E.; Jocken, J.W.; Blaak, E.E. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangiola, F.; Ianiro, G.; Franceschi, F.; Fagiuoli, S.; Gasbarrini, G.; Gasbarrini, A. Gut microbiota in autism and mood disorders. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbergen, L.; Sellaro, R.; van Hemert, S.; Bosch, J.A.; Colzato, L.S. A randomized controlled trial to test the effect of multispecies probiotics on cognitive reactivity to sad mood. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillisch, K.; Labus, J.; Kilpatrick, L.; Jiang, Z.; Stains, J.; Ebrat, B.; Guyonnet, D.; Legrain-Raspaud, S.; Trotin, B.; Naliboff, B.; et al. Consumption of Fermented Milk Product With Probiotic Modulates Brain Activity. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 1394–1401.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamm, M.A.; Dudding, T.C.; Melenhorst, J.; Jarrett, M.; Wang, Z.; Buntzen, S.; Johansson, C.; Laurberg, S.; Rosen, H.; Vaizey, C.J.; et al. Sacral nerve stimulation for intractable constipation. Gut 2010, 59, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Ganz, J.; Bayrer, J.; Becker, L.; Bogunovic, M.; Rao, M. Advances in Enteric Neurobiology: The “Brain” in the Gut in Health and Disease. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 9346–9354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Micci, M.-A.; Leser, J.; Shin, C.; Tang, S.-C.; Fu, Y.-Y.; Liu, L.; Li, Q.; Saha, M.; Li, C.; et al. Adult enteric nervous system in health is maintained by a dynamic balance between neuronal apoptosis and neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3709–E3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackeim, H.A.; Dibué, M.; Bunker, M.T.; Rush, A.J. The Long and Winding Road of Vagus Nerve Stimulation: Challenges in Developing an Intervention for Difficult-to-Treat Mood Disorders. NDT 2020, 16, 3081–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, K.N.; Verheijden, S.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. The Vagus Nerve in Appetite Regulation, Mood, and Intestinal Inflammation. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 730–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tysnes, O.; Kenborg, L.; Herlofson, K.; Steding-Jessen, M.; Horn, A.; Olsen, J.H.; Reichmann, H. Does vagotomy reduce the risk of Parkinson’s disease? Ann. Neurol. 2015, 78, 1011–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Fang, F.; Pedersen, N.L.; Tillander, A.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Ekbom, A.; Svenningsson, P.; Chen, H.; Wirdefeldt, K. Vagotomy and Parkinson disease. Neurology 2017, 88, 1996–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.Y.; Lin, C.L.; Wang, I.K.; Lin, C.C.; Lin, C.H.; Hsu, W.H.; Kao, C.H. Dementia and vagotomy in Taiwan: A population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyoz, A.H.; Christensen, R.H.B.; Orlovska-Waast, S.; Nordentoft, M.; Mortensen, P.B.; Petersen, L.V.; Benros, M.E. Vagotomy and the risk of mental disorders: A nationwide population-based study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2022, 145, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, F.A.; Chavan, S.S.; Miljko, S.; Grazio, S.; Sokolovic, S.; Schuurman, P.R.; Mehta, A.D.; Levine, Y.A.; Faltys, M.; Zitnik, R.; et al. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8284–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaz, B.; Sinniger, V.; Hoffmann, D.; Clarençon, D.; Mathieu, N.; Dantzer, C.; Vercueil, L.; Picq, C.; Trocmé, C.; Faure, P.; et al. Chronic vagus nerve stimulation in Crohn’s disease: A 6-month follow-up pilot study. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 28, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörkl, S.; Narrath, M.; Schlotmann, D.; Sallmutter, M.-T.; Putz, J.; Lang, J.; Brandstätter, A.; Pilz, R.; Lackner, H.K.; Goswami, N.; et al. Multi-species probiotic supplement enhances vagal nerve function—Results of a randomized controlled trial in patients with depression and healthy controls. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2492377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; You, X.Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Li, X.L.; Sheng, Y.Y.; Zhuang, P.W.; Zhang, Y.J. Bidirectional Brain-gut-microbiota Axis in increased intestinal permeability induced by central nervous system injury. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2020, 26, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.R.; Osadchiy, V.; Kalani, A.; Mayer, E.A. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblhuber, F.; Ehrlich, D.; Steiner, K.; Geisler, S.; Fuchs, D.; Lanser, L.; Kurz, K. The Immunopathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease Is Related to the Composition of Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hakim, Y.; Bake, S.; Mani, K.K.; Sohrabji, F. Impact of intestinal disorders on central and peripheral nervous system diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 165, 105627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavropoulou, E.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Probiotics in Medicine: A Long Debate. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraji, N.; Payami, B.; Ebadpour, N.; Gorji, A. Vagus nerve stimulation and gut microbiota interactions: A novel therapeutic avenue for neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 169, 105990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loper, H.; Leinen, M.; Bassoff, L.; Sample, J.; Romero-Ortega, M.; Gustafson, K.J.; Taylor, D.M.; Schiefer, M.A. Both high fat and high carbohydrate diets impair vagus nerve signaling of satiety. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, T.; Cawthon, C.R.; Ihde, B.T.; Hajnal, A.; DiLorenzo, P.M.; de La Serre, C.B.; Czaja, K. Diet-driven microbiota dysbiosis is associated with vagal remodeling and obesity. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 173, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waise, T.M.Z.; Toshinai, K.; Naznin, F.; NamKoong, C.; Moin, A.S.M.; Sakoda, H.; Nakazato, M. One-day high-fat diet induces inflammation in the nodose ganglion and hypothalamus of mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 464, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrignani, V.; Salvo, A.; Pacinella, G.; Tuttolomondo, A. The Mediterranean Diet, Its Microbiome Connections, and Cardiovascular Health: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malesza, I.J.; Malesza, M.; Walkowiak, J.; Mussin, N.; Walkowiak, D.; Aringazina, R.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Mądry, E. High-Fat, Western-Style Diet, Systemic Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Cells 2021, 10, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohórquez, D.V.; Shahid, R.A.; Erdmann, A.; Kreger, A.M.; Wang, Y.; Calakos, N.; Wang, F.; Liddle, R.A. Neuroepithelial circuit formed by innervation of sensory enteroendocrine cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obata, Y.; Castaño, Á.; Boeing, S.; Bon-Frauches, A.C.; Fung, C.; Fallesen, T.; de Agüero, M.G.; Yilmaz, B.; Lopes, R.; Huseynova, A.; et al. Neuronal programming by microbiota regulates intestinal physiology. Nature 2020, 578, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verheijden, S.; De Schepper, S.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. Neuron-macrophage crosstalk in the intestine: A ‘microglia’ perspective. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2015, 9, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Rios-Covian, D.; Huillet, E.; Auger, S.; Khazaal, S.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Sokol, H.; Chatel, J.-M.; Langella, P. Faecalibacterium: A bacterial genus with promising human health applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindstad, L.J.; Lo, G.; Leivers, S.; Lu, Z.; Michalak, L.; Pereira, G.V.; Røhr, Å.K.; Martens, E.C.; McKee, L.S.; Louis, P.; et al. Human Gut Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Deploys a Highly Efficient Conserved System To Cross-Feed on β-Mannan-Derived Oligosaccharides. mBio 2021, 12, e0362820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Lee, G.; Son, H.; Koh, H.; Kim, E.S.; Unno, T.; Shin, J.-H. Butyrate producers, “The Sentinel of Gut”: Their intestinal significance with and beyond butyrate, and prospective use as microbial therapeutics. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsom, L.; Faludi, M.; Fülöp, T.; Dossabhoy, N.R.; Rosivall, L.; Tapolyai, M.B. The association of overhydration with chronic inflammation in chronic maintenance hemodiafiltration patients. Hemodial. Int. Int. Symp. Home Hemodial. 2019, 23, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A.; Coppola, G.; Santopaolo, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Role of Akkermansia in Human Diseases: From Causation to Therapeutic Properties. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casertano, M.; Dekker, M.; Valentino, V.; De Filippis, F.; Fogliano, V.; Ercolini, D. Gaba-producing lactobacilli boost cognitive reactivity to negative mood without improving cognitive performance: A human Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Cross-Over study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 122, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Braun, C.; Murphy, E.F.; Enck, P. Bifidobacterium longum 1714TM Strain Modulates Brain Activity of Healthy Volunteers During Social Stress. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehme, M.; Rémond-Derbez, N.; Lerond, C.; Lavalle, L.; Keddani, S.; Steinmann, M.; Rytz, A.; Dalile, B.; Verbeke, K.; Van Oudenhove, L.; et al. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum Reduces Perceived Psychological Stress in Healthy Adults: An Exploratory Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandouzi, Z.A.; Lee, J.; Rosas, M.d.C.; Chen, J.; Henderson, W.A.; Starkweather, A.R.; Cong, X.S. Associations of neurotransmitters and the gut microbiome with emotional distress in mixed type of irritable bowel syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanidad, K.Z.; Rager, S.L.; Carrow, H.C.; Ananthanarayanan, A.; Callaghan, R.; Hart, L.R.; Li, T.; Ravisankar, P.; Brown, J.A.; Amir, M.; et al. Gut bacteria-derived serotonin promotes immune tolerance in early life. Sci. Immunol. 2024, 9, eadj4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-M.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.-L.; Hou, J.-J.; Su, S.; Zhong, W.-L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.-M.; et al. Effect of Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus faecium, and Enterococcus faecalis supernatants on serotonin transporter expression in cells and tissues. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, P.P.; Williams, P.H.; Haigh, R.D.; Maggs, A.F.; Neal, C.P.; Lyte, M. Growth stimulation of intestinal commensal Escherichia coli by catecholamines: A possible contributory factor in trauma-induced sepsis. Shock 2002, 18, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, G.; Kim, C.; Cho, U.M.; Hwang, E.T.; Hwang, H.S.; Min, J. Melanin-Decolorizing Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes, Glutathione Peroxidase, Thiol Peroxidase, and Catalase. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahesu Tabori, A.A.; Mech, E.N.; Atagi, N. Exploiting Language Variation to Better Understand the Cognitive Consequences of Bilingualism. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madariaga, A.; Garg, S.; Tchrakian, N.; Dhani, N.C.; Jimenez, W.; Welch, S.; MacKay, H.; Ethier, J.-L.; Gilbert, L.; Li, X.; et al. Clinical outcome and biomarker assessments of a multi-centre phase II trial assessing niraparib with or without dostarlimab in recurrent endometrial carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, O.; Ost, M.C. Editorial Comment. J. Urol. 2023, 209, 589–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karemaker, J.M. An introduction into autonomic nervous function. Physiol. Meas. 2017, 38, R89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.H.; Pothoulakis, C.; Mayer, E.A. Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 6, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, J.A.; Layden, B.T.; Dugas, L.R. Signalling cognition: The gut microbiota and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1130689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülling, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Gut Microbe to Brain Signaling: What Happens in Vagus. Neuron 2019, 101, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breit, S.; Kupferberg, A.; Rogler, G.; Hasler, G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, A.M.; Troisi, J.; Fasano, A.; Grave, R.D.; Marciello, F.; Serena, G.; Calugi, S.; Scala, G.; Corrivetti, G.; Cascino, G.; et al. Multi-omics data integration in anorexia nervosa patients before and after weight regain: A microbiome-metabolomics investigation. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Bonfili, L.; Wei, T.; Eleuteri, A.M. Understanding the Gut-Brain Axis and Its Therapeutic Implications for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Q.L.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, P.H. Enteric Nervous System: The Bridge Between the Gut Microbiota and Neurological Disorders. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 810483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouanes, S.; Popp, J. High Cortisol and the Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of the Literature. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.X.; Wang, Y.P. Gut Microbiota-brain Axis. Chin. Med. J. 2016, 129, 2373–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocetta, A.; Liloia, D.; Costa, T.; Duca, S.; Cauda, F.; Manuello, J. From gut to brain: Unveiling probiotic effects through a neuroimaging perspective-A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1446854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Husseini, A.E.D.; Schnell, E.; Chetkovich, D.M.; Nicoll, R.A.; Bredt, D.S. PSD-95 Involvement in Maturation of Excitatory Synapses. Science 2000, 290, 1364–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.E.; Chapman, E.R. Synaptophysin Regulates the Kinetics of Synaptic Vesicle Endocytosis in Central Neurons. Neuron 2011, 70, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczynski, P.; McVey Neufeld, K.A.; Oriach, C.S.; Clarke, G.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Growing up in a Bubble: Using Germ-Free Animals to Assess the Influence of the Gut Microbiota on Brain and Behavior. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 19, pyw020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoretti, M.; Amsler, C.; Bonomi, G.; Bouchta, A.; Bowe, P.; Carraro, C.; Cesar, C.L.; Charlton, M.; Collier, M.J.T.; Doser, M.; et al. Production and detection of cold antihydrogen atoms. Nature 2002, 419, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourassa, M.W.; Alim, I.; Bultman, S.J.; Ratan, R.R. Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: Can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 625, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Muinck, E.J.; Lundin, K.E.A.; Trosvik, P. Linking Spatial Structure and Community-Level Biotic Interactions through Cooccurrence and Time Series Modeling of the Human Intestinal Microbiota. mSystems 2017, 2, e00086-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Dawson, T.M.; Kulkarni, S. Neurodegenerative disorders and gut-brain interactions. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e143775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rea, K.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The microbiome: A key regulator of stress and neuroinflammation. Neurobiol. Stress 2016, 4, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Haq, R.; Schlachetzki, J.C.M.; Glass, C.K.; Mazmanian, S.K. Microbiome-microglia connections via the gut-brain axis. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 216, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Dittel, B.N. Interrelatedness between dysbiosis in the gut microbiota due to immunodeficiency and disease penetrance of colitis. Immunology 2015, 146, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omenetti, S.; Pizarro, T.T. The Treg/Th17 Axis: A Dynamic Balance Regulated by the Gut Microbiome. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, O.I.; Haller, D. Bacterial Signaling at the Intestinal Epithelial Interface in Inflammation and Cancer. Front Immunol 2018, 8, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolig, A.S.; Mittge, E.K.; Ganz, J.; Troll, J.V.; Melancon, E.; Wiles, T.J.; Alligood, K.; Stephens, W.Z.; Eisen, J.S.; Guillemin, K. The enteric nervous system promotes intestinal health by constraining microbiota composition. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2000689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, G.; Gitler, A.D.; Brahic, M. Internalization, axonal transport and release of fibrillar forms of alpha-synuclein. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 109, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg, A.; Tsou, V.T.; Müller, A.D. The “institutional colon”: A frequent colonic dysmotility in psychiatric and neurologic disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1994, 89, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, P.; Park, H.; Baumann, M.; Dunlop, J.; Frydman, J.; Kopito, R.; McCampbell, A.; Leblanc, G.; Venkateswaran, A.; Nurmi, A.; et al. Protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases: Implications and strategies. Transl. Neurodegener. 2017, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, A.; Fraldi, A. Protein Aggregation and Dysfunction of Autophagy-Lysosomal Pathway: A Vicious Cycle in Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Telpoukhovskaia, M.A.; Bahr, B.A.; Chen, X.; Gan, L. Endo-lysosomal dysfunction: A converging mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018, 48, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.Y.; Kim, H.N.; Hwang, J.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, S.E. Lysosomal dysfunction in proteinopathic neurodegenerative disorders: Possible therapeutic roles of cAMP and zinc. Mol. Brain 2019, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochocka, M.; Donskow-Łysoniewska, K.; Diniz, B.S.; Kurpas, D.; Brzozowska, E.; Leszek, J. The Gut Microbiome Alterations and Inflammation-Driven Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease-a Critical Review. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louveau, A.; Herz, J.; Alme, M.N.; Salvador, A.F.; Dong, M.Q.; Viar, K.E.; Herod, S.G.; Knopp, J.; Setliff, J.C.; Lupi, A.L.; et al. CNS lymphatic drainage and neuroinflammation are regulated by meningeal lymphatic vasculature. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1380–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, K.; Nakajima, K. Role of the Immune System in the Development of the Central Nervous System. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoharan, I.; Suryawanshi, A.; Hong, Y.; Ranganathan, P.; Shanmugam, A.; Ahmad, S.; Swafford, D.; Manicassamy, B.; Ramesh, G.; Koni, P.A.; et al. Homeostatic PPARα Signaling Limits Inflammatory Responses to Commensal Microbiota in the Intestine. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 4739–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, C.J.; Zheng, L.; Campbell, E.L.; Saeedi, B.; Scholz, C.C.; Bayless, A.J.; Wilson, K.E.; Glover, L.E.; Kominsky, D.J.; Magnuson, A.; et al. Crosstalk between Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Intestinal Epithelial HIF Augments Tissue Barrier Function. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefano, G.B.; Pilonis, N.; Ptacek, R.; Raboch, J.; Vnukova, M.; Kream, R.M. Gut, Microbiome, and Brain Regulatory Axis: Relevance to Neurodegenerative and Psychiatric Disorders. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 38, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.; Das, D.K.; Pahari, S.; Nadeem, S.; Agrewala, J.N. Potential Role of Gut Microbiota in Induction and Regulation of Innate Immune Memory. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erny, D.; Hrabě de Angelis, A.L.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer, P.; Staszewski, O.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T.; et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Emge, J.R.; Berzins, K.; Lung, L.; Khamishon, R.; Shah, P.; Rodrigues, D.M.; Sousa, A.J.; Reardon, C.; Sherman, P.M.; et al. Probiotics normalize the gut-brain-microbiota axis in immunodeficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2014, 307, G793–G802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, N.; Su, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, R. Gut-Microbiota-Derived Metabolites Maintain Gut and Systemic Immune Homeostasis. Cells 2023, 12, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hussain, B.; Chang, J. Peripheral inflammation and blood-brain barrier disruption: Effects and mechanisms. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2021, 27, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, B.; Lou, P.; Dai, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhuge, A.; Yuan, Y.; Li, L. The Relationship Between the Gut Microbiome and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurosci. Bull. 2021, 37, 1510–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huh, J.R.; Shah, K. Microbiota and the gut-brain-axis: Implications for new therapeutic design in the CNS. EBioMedicine 2022, 77, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Almanzar, N.; Chiu, I.M. The role of cellular and molecular neuroimmune crosstalk in gut immunity. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Miao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Su, J.; Chen, J. The Brain-Gut-Bone Axis in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Insights, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2307971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, M.L.; Meccia, J.; Phillips, A.G.; Floresco, S.B. Amelioration of cognitive impairments induced by GABA hypofunction in the male rat prefrontal cortex by direct and indirect dopamine D1 agonists SKF-81297 and d-Govadine. Neuropharmacology 2020, 162, 107844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, E.M.; Stagg, A.J. Type 1 Interferon in the Human Intestine-A Co-ordinator of the Immune Response to the Microbiota. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-E.; Lim, S.-M.; Jeong, J.-J.; Jang, H.-M.; Lee, H.-J.; Han, M.J.; Kim, D.-H. Gastrointestinal inflammation by gut microbiota disturbance induces memory impairment in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiecker, C. The origins of the circumventricular organs. J. Anat. 2018, 232, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, K.M.; Nelson, L.H. Microglia and Beyond: Innate Immune Cells As Regulators of Brain Development and Behavioral Function. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thion, M.S.; Low, D.; Silvin, A.; Chen, J.; Grisel, P.; Schulte-Schrepping, J.; Blecher, R.; Ulas, T.; Squarzoni, P.; Hoeffel, G.; et al. Microbiome Influences Prenatal and Adult Microglia in a Sex-Specific Manner. Cell 2018, 172, 500–516.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadowaki, A.; Miyake, S.; Saga, R.; Chiba, A.; Mochizuki, H.; Yamamura, T. Gut environment-induced intraepithelial autoreactive CD4+ T cells suppress central nervous system autoimmunity via LAG-3. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhle, L.; Mattei, D.; Heimesaat, M.M.; Bereswill, S.; Fischer, A.; Alutis, M.; French, T.; Hambardzumyan, D.; Matzinger, P.; Dunay, I.R.; et al. Ly6Chi Monocytes Provide a Link between Antibiotic-Induced Changes in Gut Microbiota and Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cong, L.; Jaber, V.; Lukiw, W.J. Microbiome-Derived Lipopolysaccharide Enriched in the Perinuclear Region of Alzheimer’s Disease Brain. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat, A.M.; Srinivasan, N.; Maloy, K.J. Modulation of immune development and function by intestinal microbiota. Trends Immunol. 2014, 35, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesemann, D.R.; Portuguese, A.J.; Meyers, R.M.; Gallagher, M.P.; Cluff-Jones, K.; Magee, J.M.; Panchakshari, R.A.; Rodig, S.J.; Kepler, T.B.; Alt, F.W. Microbial colonization influences early B-lineage development in the gut lamina propria. Nature 2013, 501, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonini, M.; Lo Conte, M.; Sorini, C.; Falcone, M. How the Interplay Between the Commensal Microbiota, Gut Barrier Integrity, and Mucosal Immunity Regulates Brain Autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaji, R.; Kiyoshima-Shibata, J.; Nagaoka, M.; Nanno, M.; Shida, K. Bacterial teichoic acids reverse predominant IL-12 production induced by certain lactobacillus strains into predominant IL-10 production via TLR2-dependent ERK activation in macrophages. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 3505–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smythies, L.E.; Sellers, M.; Clements, R.H.; Mosteller-Barnum, M.; Meng, G.; Benjamin, W.H.; Orenstein, J.M.; Smith, P.D. Human intestinal macrophages display profound inflammatory anergy despite avid phagocytic and bacteriocidal activity. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley-McBain, T.; Wu, M.C.; A Manuzak, J.; Cheu, R.K.; Gustin, A.; Driscoll, C.B.; Zevin, A.S.; Miller, C.J.; Coronado, E.; Smith, E.; et al. Increased mucosal neutrophil survival is associated with altered microbiota in HIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanson, D.L.; Bendzick, L.; Pribyl, L.; McCullar, V.; Vogel, R.I.; Miller, J.S.; Geller, M.A.; Kaufman, D.S. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Natural Killer Cells for Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Stem Cells 2016, 34, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romee, R.; Rosario, M.; Berrien-Elliott, M.M.; Wagner, J.A.; Jewell, B.A.; Schappe, T.; Leong, J.W.; Abdel-Latif, S.; Schneider, S.E.; Willey, S.; et al. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells exhibit enhanced responses against myeloid leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 357ra123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merle, N.S.; Noe, R.; Halbwachs-Mecarelli, L.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Roumenina, L.T. Complement System Part II: Role in Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.S.; Rutherfurd, K.J.; Cross, M.L.; Gopal, P.K. Enhancement of immunity in the elderly by dietary supplementation with the probiotic Bifidobacterium lactis HN019. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, A.M.; Gibbs, R.S.; Murphy, J.R.; Giclas, P.C.; Salmon, J.E.; Holers, V.M. Early elevations of the complement activation fragment C3a and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Obs. Gynecol. 2011, 117, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissilä, E.; Korpela, K.; Lokki, A.I.; Paakkanen, R.; Jokiranta, S.; de Vos, W.M.; Lokki, M.-L.; Kolho, K.-L.; Meri, S. C4B gene influences intestinal microbiota through complement activation in patients with paediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017, 190, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.J.; Pino-Lagos, K.; Rosemblatt, M.; Noelle, R.J. All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, M.; Weigand, K.; Wedi, F.; Breidenbend, C.; Leister, H.; Pautz, S.; Adhikary, T.; Visekruna, A. Regulation of the effector function of CD8+ T cells by gut microbiota-derived metabolite butyrate. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, K.; Ogawa, A.; Mizoguchi, E.; Shimomura, Y.; Andoh, A.; Bhan, A.K.; Blumberg, R.S.; Xavier, R.J.; Mizoguchi, A. IL-22 ameliorates intestinal inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Tian, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, F.; Ge, Q.; et al. B Cells Are the Dominant Antigen-Presenting Cells that Activate Naive CD4+ T Cells upon Immunization with a Virus-Derived Nanoparticle Antigen. Immunity 2018, 49, 695–708.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzaro, J.R.; Strauss, J.D.; Bielecka, A.; Porto, A.F.; Lobo, F.M.; Urban, A.; Schofield, W.B.; Palm, N.W. IgA-deficient humans exhibit gut microbiota dysbiosis despite secretion of compensatory IgM. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, A.N.; Goel, A.; Singh, A.; Sasi, A.; Aggarwal, R. Faecal bacterial microbiota in patients with cirrhosis and the effect of lactulose administration. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, G.B.; Keating, D.J.; Young, R.L.; Wong, M.L.; Licinio, J.; Wesselingh, S. From gut dysbiosis to altered brain function and mental illness: Mechanisms and pathways. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarville, J.L.; Chen, G.Y.; Cuevas, V.D.; Troha, K.; Ayres, J.S. Microbiota Metabolites in Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, A.A.B. Tryptophan availability for kynurenine pathway metabolism across the life span: Control mechanisms and focus on aging, exercise, diet and nutritional supplements. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roager, H.M.; Licht, T.R. Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.B.; Van Benschoten, A.H.; Cimermancic, P.; Donia, M.S.; Zimmermann, M.; Taketani, M.; Ishihara, A.; Kashyap, P.C.; Fraser, J.S.; Fischbach, M.A. Discovery and characterization of gut microbiota decarboxylases that can produce the neurotransmitter tryptamine. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 16, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A.; Nega, M.; Nguyen, M.T.; Ebner, P.; Götz, F. SadA-Expressing Staphylococci in the Human Gut Show Increased Cell Adherence and Internalization. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. Regulation of Neurotransmitters by the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Cognition in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelberer, M.M.; Rupprecht, L.E.; Liu, W.W.; Weng, P.; Bohórquez, D.V. Neuropod Cells: The Emerging Biology of Gut-Brain Sensory Transduction. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 43, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandwitz, P.; Kim, K.H.; Terekhova, D.; Liu, J.K.; Sharma, A.; Levering, J.; McDonald, D.; Dietrich, D.; Ramadhar, T.R.; Lekbua, A.; et al. GABA-modulating bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, K.G.; Olson, C.A.; Kazmi, S.A.; Hsiao, E.Y. Toward Understanding Microbiome-Neuronal Signaling. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, R.I.; Niculescu, A.G.; Roza, E.; Vladâcenco, O.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, D.M. Neurotransmitters-Key Factors in Neurological and Neurodegenerative Disorders of the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaelberer, M.M.; Buchanan, K.L.; Klein, M.E.; Barth, B.B.; Montoya, M.M.; Shen, X.; Bohórquez, D.V. A gut-brain neural circuit for nutrient sensory transduction. Science 2018, 361, eaat5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragozá, R. Transport of Amino Acids Across the Blood-Brain Barrier. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siragusa, S.; De Angelis, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Coda, R.; Gobbetti, M. Synthesis of gamma-aminobutyric acid by lactic acid bacteria isolated from a variety of Italian cheeses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 7283–7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.C.; Vuong, H.E.; Luna, C.D.G.; Pronovost, G.N.; Aleksandrova, A.A.; Riley, N.G.; Vavilina, A.; McGinn, J.; Rendon, T.; Forrest, L.R.; et al. Intestinal serotonin and fluoxetine exposure modulate bacterial colonization in the gut. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 2064–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.-M.; Cuello, A.C.; Farlow, M.R.; Giacobini, E.; Grossberg, G.T.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Cavedo, E.; Snyder, P.J.; et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2018, 141, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekke, E.; Morken, T.S.; Walls, A.B.; Waagepetersen, H.; Schousboe, A.; Sonnewald, U. Anaplerosis for Glutamate Synthesis in the Neonate and in Adulthood. Adv. Neurobiol. 2016, 13, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.H.; Lin, C.H.; Lane, H.Y. d-glutamate and Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, G.; Sleeth, M.L.; Sahuri-Arisoylu, M.; Lizarbe, B.; Cerdan, S.; Brody, L.; Anastasovska, J.; Ghourab, S.; Hankir, M.; Zhang, S.; et al. The short-chain fatty acid acetate reduces appetite via a central homeostatic mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, M.P.; Fox, B.W.; Chao, P.H.; Schroeder, F.C.; Sengupta, P. A neurotransmitter produced by gut bacteria modulates host sensory behaviour. Nature 2020, 583, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Vieira, T.H.; Guimaraes, I.M.; Silva, F.R.; Ribeiro, F.M. Alzheimer’s disease: Targeting the Cholinergic System. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koussoulas, K.; Swaminathan, M.; Fung, C.; Bornstein, J.C.; Foong, J.P.P. Neurally Released GABA Acts via GABAC Receptors to Modulate Ca2+ Transients Evoked by Trains of Synaptic Inputs, but Not Responses Evoked by Single Stimuli, in Myenteric Neurons of Mouse Ileum. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amenta, F.; Tayebati, S.K. Pathways of acetylcholine synthesis, transport and release as targets for treatment of adult-onset cognitive dysfunction. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masato, A.; Plotegher, N.; Boassa, D.; Bubacco, L. Impaired dopamine metabolism in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de JRDe-Paula, V.; Forlenza, A.S.; Forlenza, O.V. Relevance of gutmicrobiota in cognition, behaviour and Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 136, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helton, S.G.; Lohoff, F.W. Serotonin pathway polymorphisms and the treatment of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. Pharmacogenomics 2015, 16, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Ooga, T.; Kibe, R.; Aiba, Y.; Koga, Y.; Benno, Y. Colonic Absorption of Low-Molecular-Weight Metabolites Influenced by the Intestinal Microbiome: A Pilot Study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, T.B.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wen, J.; Deng, K.; Qin, X.W.; Wang, D.H. The microbiota-gut-brain interaction in regulating host metabolic adaptation to cold in male Brandt’s voles (Lasiopodomys brandtii). ISME J. 2019, 13, 3037–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Lee, Y.; Lee, G.H. The regulation of glutamic acid decarboxylases in GABA neurotransmission in the brain. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2019, 42, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Pan, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W.; Wang, X. Intestinal Crosstalk between Microbiota and Serotonin and its Impact on Gut Motility. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2018, 19, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proano, A.C.; Viteri, J.A.; Orozco, E.N.; Calle, M.A.; Costa, S.C.; Reyes, D.V.; German-Montenegro, M.; Moncayo, D.F.; Tobar, A.C.; Moncayo, J.A. Gut Microbiota and Its Repercussion in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review in Occidental Patients. Neurol. Int. 2023, 15, 750–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Liao, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.-T.; Wu, Y.-W.; Liou, J.-M.; Wu, M.-S.; Kuo, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H. Association of Fecal and Plasma Levels of Short-Chain Fatty Acids With Gut Microbiota and Clinical Severity in Patients With Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2022, 98, e848–e858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, S.; Wang, J.; Deng, Y.; Ye, Z.; Ge, Y. Inflammatory microbes and genes as potential biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K.; Qu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Mao, Z.; Xue, Z. Associations of diet-derived short chain fatty acids with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Neurosci. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnicar, F.; Leeming, E.R.; Dimidi, E.; Mazidi, M.; Franks, P.W.; Al Khatib, H.; Valdes, A.M.; Davies, R.; Bakker, E.; Francis, L.; et al. Blue poo: Impact of gut transit time on the gut microbiome using a novel marker. Gut 2021, 70, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, C.; Fornai, M.; D’Antongiovanni, V.; Antonioli, L.; Bernardini, N.; Derkinderen, P. The intestinal barrier in disorders of the central nervous system. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, M.; Nishiwaki, H.; Hamaguchi, T.; Ohno, K. Gastrointestinal disorders in Parkinson’s disease and other Lewy body diseases. npj Park. Dis. 2023, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, C.-M.; Sun, M.-F.; Jia, X.-B.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, B.-P.; Zhou, Z.-L.; Zhao, L.-P.; Cui, C.; Shen, Y.-Q. Sodium butyrate causes α-synuclein degradation by an Atg5-dependent and PI3K/Akt/mTOR-related autophagy pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 387, 111772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Seo, S.U.; Kweon, M.N. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites tune host homeostasis fate. Semin. Immunopathol. 2024, 46, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Q.; Su, R. Interplay of human gastrointestinal microbiota metabolites: Short-chain fatty acids and their correlation with Parkinson’s disease. Medicine 2024, 103, e37960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Tan, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Feng, W.; Peng, C. Functions of Gut Microbiota Metabolites, Current Status and Future Perspectives. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; An, K.; Wang, D.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Min, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Xue, Z.; Mao, Z. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Aggregates Alpha-Synuclein Accumulation and Neuroinflammation via GPR43-NLRP3 Signaling Pathway in a Model Parkinson’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, K.A.; Boobis, A.R.; Chiodini, A.; Edwards, C.A.; Franck, A.; Kleerebezem, M.; Nauta, A.; Raes, J.; Van Tol, E.A.F.; Tuohy, K.M. Towards microbial fermentation metabolites as markers for health benefits of prebiotics. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2015, 28, 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.J.A.; Santos, A.; Prada, P.O. Linking Gut Microbiota and Inflammation to Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Physiology 2016, 31, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchin, S.; Calgaro, M.; Savarino, E.V. Rethinking Short-Chain Fatty Acids: A Closer Look at Propionate in Inflammation, Metabolism, and Mucosal Homeostasis. Cells 2025, 14, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Lithgow, G.J.; Link, W. Long live FOXO: Unraveling the role of FOXO proteins in aging and longevity. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, E.; Amamoto, R.; Zheng, L.; Cacquevel, M.; Sarria, J.-C.; Knott, G.W.; Schneider, B.L. FOXO3 determines the accumulation of α-synuclein and controls the fate of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 1435–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, N.; Agis-Balboa, R.C.; Walter, J.; Sananbenesi, F.; Fischer, A. Sodium Butyrate Improves Memory Function in an Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model When Administered at an Advanced Stage of Disease Progression. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011, 26, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.; Canfield, J.; Copes, N.; Rehan, M.; Lipps, D.; Bradshaw, P.C. D-beta-hydroxybutyrate extends lifespan in C. elegans. Aging 2014, 6, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Li, H.; Jin, Y.; Yu, J.; Mao, S.; Su, K.-P.; Ling, Z.; Liu, J. Probiotic Clostridium butyricum ameliorated motor deficits in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease via gut microbiota-GLP-1 pathway. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 91, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, K.; Bjornevik, K.; Abu-Ali, G.; Chan, J.; Cortese, M.; Dedi, B.; Jeon, M.; Xavier, R.; Huttenhower, C.; Ascherio, A.; et al. The human gut microbiota in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2021, 22, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, S.; Lomis, N.; Kahouli, I.; Dia, S.Y.; Singh, S.P.; Prakash, S. Microbiome, probiotics and neurodegenerative diseases: Deciphering the gut brain axis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 3769–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.H.; Lim, S.-Y.; Chong, K.K.; A Manap, M.A.A.; Hor, J.W.; Lim, J.L.; Low, S.C.; Chong, C.W.; Mahadeva, S.; Lang, A.E. Probiotics for Constipation in Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2021, 96, e772–e782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Ali, R.A.R.; Manaf, M.R.A.; Ahmad, N.; Tajurruddin, F.W.; Qin, W.Z.; Desa, S.H.M.; Ibrahim, N.M. Multi-strain probiotics (Hexbio) containing MCP BCMC strains improved constipation and gut motility in Parkinson’s disease: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Cao, K.A.L.; Judd, L.M.; Li, S.; Renoir, T.; Hannan, A.J. Microbiome profiling reveals gut dysbiosis in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 135, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulescu, C.I.; Garcia-Miralles, M.; Sidik, H.; Bardile, C.F.; Yusof, N.A.B.M.; Lee, H.U.; Ho, E.X.P.; Chu, C.W.; Layton, E.; Low, D.; et al. Reprint of: Manipulation of microbiota reveals altered callosal myelination and white matter plasticity in a model of Huntington disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 135, 104744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosorich, I.; Dalla-Costa, G.; Sorini, C.; Ferrarese, R.; Messina, M.J.; Dolpady, J.; Radice, E.; Mariani, A.; Testoni, P.A.; Canducci, F.; et al. High frequency of intestinal TH17 cells correlates with microbiota alterations and disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chia, N.; Kalari, K.R.; Yao, J.Z.; Novotna, M.; Paz Soldan, M.M.; Luckey, D.H.; Marietta, E.V.; Jeraldo, P.R.; Chen, X.; et al. Multiple sclerosis patients have a distinct gut microbiota compared to healthy controls. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uematsu, M.; Nakamura, A.; Ebashi, M.; Hirokawa, K.; Takahashi, R.; Uchihara, T. Brainstem tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by increase of three repeat tau and independent of amyloid β. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Altomare, D.; Thal, D.R.; Ribaldi, F.; van der Kant, R.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Blennow, K.; Cummings, J.; van Duijn, C.; Nilsson, P.M.; et al. The probabilistic model of Alzheimer disease: The amyloid hypothesis revised. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 23, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gieryńska, M.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Struzik, J.; Mielcarska, M.B.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P. Integrity of the Intestinal Barrier: The Involvement of Epithelial Cells and Microbiota-A Mutual Relationship. Animals 2022, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytriv, T.R.; Storey, K.B.; Lushchak, V.I. Intestinal barrier permeability: The influence of gut microbiota, nutrition, and exercise. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1380713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.G.B.; Mead, S.H. Review: Fluid biomarkers in the human prion diseases. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 97, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelakkot, C.; Ghim, J.; Ryu, S.H. Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, R.L.; Juritsch, A.F.; Ahmad, R.; Salomon, J.D.; Dhawan, P.; Ramer-Tait, A.E.; Singh, A.B. The diet-microbiota axis: A key regulator of intestinal permeability in human health and disease. Tissue Barriers 2023, 11, 2077069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGruttola, A.K.; Low, D.; Mizoguchi, A.; Mizoguchi, E. Current Understanding of Dysbiosis in Disease in Human and Animal Models. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1137–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, N.; Lécuyer, E.; Chassaing, B. Host/microbiota interactions in health and diseases-Time for mucosal microbiology! Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Yoneda, T.; Kikuchi, M.; Sugimoto, R.; Shimizu, Y.; Ayabe, T. Paneth cell granule dynamics on secretory responses to bacterial stimuli in enteroids. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonis, V.; Rossell, C.; Gehart, H. The Intestinal Epithelium—Fluid Fate and Rigid Structure From Crypt Bottom to Villus Tip. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 661931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, A.M.; Loke, P. Intestinal Macrophages in Resolving Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadoni, I.; Zagato, E.; Bertocchi, A.; Paolinelli, R.; Hot, E.; Di Sabatino, A.; Caprioli, F.; Bottiglieri, L.; Oldani, A.; Viale, G.; et al. A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science 2015, 350, 830–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanuytsel, T.; Tack, J.; Farre, R. The Role of Intestinal Permeability in Gastrointestinal Disorders and Current Methods of Evaluation. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 717925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, M.J.; Cusack, S.; O’Sullivan, O.; Greene-Diniz, R.; De Weerd, H.; Flannery, E.; Marchesi, J.R.; Falush, D.; Dinan, T.G.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4586–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syeda, T.; Sanchez-Tapia, M.; Pinedo-Vargas, L.; Granados, O.; Cuervo-Zanatta, D.; Rojas-Santiago, E.; A Díaz-Cintra, S.; Torres, N.; Perez-Cruz, C. Bioactive Food Abates Metabolic and Synaptic Alterations by Modulation of Gut Microbiota in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 66, 1657–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sterling, K.; Song, W. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in Alzheimer’s disease and its pharmaceutical potential. Transl. Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsom, E.M.; Lee, K.; Cope, E.K. Do the Bugs in Your Gut Eat Your Memories? Relationship between Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, M.; Pecoraro, H.L.; Combs, C.K. Gut Inflammation Induced by Dextran Sulfate Sodium Exacerbates Amyloid-β Plaque Deposition in the AppNL-G-F Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 79, 1235–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiihonen, K.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Rautonen, N. Human intestinal microbiota and healthy ageing. Ageing Res. Rev. 2010, 9, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marizzoni, M.; Cattaneo, A.; Mirabelli, P.; Festari, C.; Lopizzo, N.; Nicolosi, V.; Mombelli, E.; Mazzelli, M.; Luongo, D.; Naviglio, D.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Lipopolysaccharide as Mediators Between Gut Dysbiosis and Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 78, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minter, M.R.; Hinterleitner, R.; Meisel, M.; Zhang, C.; Leone, V.; Zhang, X.; Oyler-Castrillo, P.; Zhang, X.; Musch, M.W.; Shen, X.; et al. Antibiotic-induced perturbations in microbial diversity during post-natal development alters amyloid pathology in an aged APPSWE/PS1ΔE9 murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, S. Rapid improvement in Alzheimer’s disease symptoms following fecal microbiota transplantation: A case report. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 0300060520925930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-S.; Kim, Y.; Choi, H.; Kim, W.; Park, S.; Lee, D.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, H.; Hyun, D.-W.; et al. Transfer of a healthy microbiota reduces amyloid and tau pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Gut 2020, 69, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzhaki, R.F.; Lathe, R.; Balin, B.J.; Ball, M.J.; Bearer, E.L.; Braak, H.; Bullido, M.J.; Carter, C.; Clerici, M.; Cosby, S.L.; et al. Microbes and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 51, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerven, N.; Van der Verren, S.E.; Reiter, D.M.; Remaut, H. The Role of Functional Amyloids in Bacterial Virulence. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 3657–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodiya, H.B.; Kuntz, T.; Shaik, S.M.; Baufeld, C.; Leibowitz, J.; Zhang, X.; Gottel, N.; Zhang, X.; Butovsky, O.; Gilbert, J.A.; et al. Sex-specific effects of microbiome perturbations on cerebral Aβ amyloidosis and microglia phenotypes. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 1542–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadou, E.G.; Katsipis, G.; Tsolaki, M.; Pantazaki, A.A. Involvement and relationship of bacterial lipopolysaccharides and cyclooxygenases levels in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 357, 577561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Bi, W.; Xiao, S.; Lan, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Lu, D.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment in mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, A.J.; Underhill, D.M. Peptidoglycan recognition by the innate immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetz, G.; Pinho, M.; Pritzkow, S.; Mendez, N.; Soto, C.; Tetz, V. Bacterial DNA promotes Tau aggregation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.; Ono, K.; Tsuji, M.; Mazzola, P.; Singh, R.; Pasinetti, G.M. Protective roles of intestinal microbiota derived short chain fatty acids in Alzheimer’s disease-type beta-amyloid neuropathological mechanisms. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2018, 18, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zheng, S.J.; Cai, W.J.; Yu, L.; Yuan, B.F.; Feng, Y.Q. Stable isotope labeling combined with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for comprehensive analysis of short-chain fatty acids. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1070, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, S.M.; DeMorrow, S. Bile Acid Signaling in Neurodegenerative and Neurological Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Ke, Y.; Zhan, R.; Liu, C.; Zhao, M.; Zeng, A.; Shi, X.; Ji, L.; Cheng, S.; Pan, B.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide promotes brain aging and cognitive impairment in mice. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.-T. Decreased levels of circulating trimethylamine N-oxide alleviate cognitive and pathological deterioration in transgenic mice: A potential therapeutic approach for Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 2019, 11, 8642–8663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciminelli, B.M.; Menduti, G.; Benussi, L.; Ghidoni, R.; Binetti, G.; Squitti, R.; Rongioletti, M.; Nica, S.; Novelletto, A.; Rossi, L.; et al. Polymorphic Genetic Markers of the GABA Catabolism Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 77, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, K.; Nalla, L.V.; Naresh, D.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Viswanadh, M.K.; Nalluri, B.N.; Chakravarthy, G.; Duguluri, S.; Singh, P.; Rai, S.N.; et al. WNT-β Catenin Signaling as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Status and Future Perspective. Diseases 2023, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xian, X.; Xu, G.; Tan, Z.; Dong, F.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, F. Toll-Like Receptor 4: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2022, 2022, 7924199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Sisodia, S.S.; Vassar, R.J. The gut microbiome in Alzheimer’s disease: What we know and what remains to be explored. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, M.; Raj, K.; Singh, S. Relevance of gut microbiota to Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): Potential effects of probiotic in management of AD. Aging Health Res. 2023, 3, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.G.; Cha, M.-Y.; Kim, J.-I.; Hwang, T.W.; Kim, K.A.; Kim, T.H.; Song, K.C.; Kim, J.-J.; Moon, M. Vitamin D-binding protein-loaded PLGA nanoparticles suppress Alzheimer’s disease-related pathology in 5XFAD mice. Nanomedicine 2019, 17, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depypere, H.; Vierin, A.; Weyers, S.; Sieben, A. Alzheimer’s disease, apolipoprotein E and hormone replacement therapy. Maturitas 2016, 94, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, R.M.; Palesi, F.; Castellazzi, G.; Vitali, P.; Anzalone, N.; Bernini, S.; Ramusino, M.C.; Sinforiani, E.; Micieli, G.; Costa, A.; et al. Unsuspected Involvement of Spinal Cord in Alzheimer Disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.-Q.; Shen, L.-L.; Li, W.-W.; Fu, X.; Zeng, F.; Gui, L.; Lü, Y.; Cai, M.; Zhu, C.; Tan, Y.-L.; et al. Gut Microbiota is Altered in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 63, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominy, S.S.; Lynch, C.; Ermini, F.; Benedyk, M.; Marczyk, A.; Konradi, A.; Nguyen, M.; Haditsch, U.; Raha, D.; Griffin, C.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Readhead, B.; Haure-Mirande, J.V.; Ehrlich, M.E.; Gandy, S.; Dudley, J.T. Clarifying the Potential Role of Microbes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 104, 1036–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cao, J.; Gong, C.; Amakye, W.K.; Yao, M.; Ren, J. Exploring the microbiota-Alzheimer’s disease linkage using short-term antibiotic treatment followed by fecal microbiota transplantation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 96, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honarpisheh, P.; Reynolds, C.R.; Conesa, M.P.B.; Manchon, J.F.M.; Putluri, N.; Bhattacharjee, M.B.; Urayama, A.; McCullough, L.D.; Ganesh, B.P. Dysregulated Gut Homeostasis Observed Prior to the Accumulation of the Brain Amyloid-β in Tg2576 Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, J.Z. Nature of Tau-Associated Neurodegeneration and the Molecular Mechanisms. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2018, 62, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chok, K.C.; Ng, K.Y.; Koh, R.Y.; Chye, S.M. Role of the gut microbiome in Alzheimer’s disease. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 32, 767–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-García, A.M.; Villarino, M.; Arias, N. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Basal Microbiota and Cognitive Function in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Potential Target for Treatment or a Contributor to Disease Progression? Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2024, 16, e70057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmeier, D.J.; Guzman, J.N.; Sanchez-Padilla, J.; Goldberg, J.A. Chapter 4—What causes the death of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease? In Progress in Brain Research; Björklund, A., Cenci, M.A., Eds.; Recent Advances in Parkinson’s Disease: Basic Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 183, pp. 59–77. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0079612310830043 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Przedborski, S. The two-century journey of Parkinson disease research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, J.Y.; Grudina, C.; Zurzolo, C. The prion-like spreading of α-synuclein: From in vitro to in vivo models of Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 50, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmoradian, S.H.; Lewis, A.J.; Genoud, C.; Hench, J.; Moors, T.E.; Navarro, P.P.; Castaño-Díez, D.; Schweighauser, G.; Graff-Meyer, A.; Goldie, K.N.; et al. Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease consists of crowded organelles and lipid membranes. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Tredici, K.D.; Rüb, U.; de Vos, R.A.I.; Jansen Steur, E.N.H.; Braak, E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2003, 24, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, J.; Du, J.; Wang, F.; Fang, R.; Yu, C.; Xiong, J.; Chen, W.; Lu, Z.; Liu, J. Clostridium butyricum exerts a neuroprotective effect in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury via the gut-brain axis. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 30, e13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredsson, F.P.; Luk, K.C.; Benskey, M.J.; Gezer, A.; Garcia, J.; Kuhn, N.C.; Sandoval, I.M.; Patterson, J.R.; O’MAra, A.; Yonkers, R.; et al. Induction of alpha-synuclein pathology in the enteric nervous system of the rat and non-human primate results in gastrointestinal dysmotility and transient CNS pathology. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 112, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, S.-H.; Kam, T.-I.; Panicker, N.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, W.R.; Kook, M.; Foss, C.A.; et al. Transneuronal Propagation of Pathologic α-Synuclein from the Gut to the Brain Models Parkinson’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 103, 627–641.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Fan, R.; Wang, P.; Zheng, L.; Hong, F.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Alteration of enteric monoamines with monoamine receptors and colonic dysmotility in 6-hydroxydopamine-induced Parkinson’s disease rats. Transl. Res. 2015, 166, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis, C.; Hori, A.; Sampson, T.R.; Yoo, B.B.; Challis, R.C.; Hamilton, A.M.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Volpicelli-Daley, L.A.; Gradinaru, V. Gut-seeded α-synuclein fibrils promote gut dysfunction and brain pathology specifically in aged mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandres-Ciga, S.; Diez-Fairen, M.; Kim, J.J.; Singleton, A.B. Genetics of Parkinson’s disease: An introspection of its journey towards precision medicine. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 137, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.-M.; Li, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Gaborit, N.; Pani, A.K.; Orrison, B.M.; Bruneau, B.G.; Giasson, B.I.; Smeyne, R.J.; Gershon, M.D.; et al. Extensive enteric nervous system abnormalities in mice transgenic for artificial chromosomes containing Parkinson disease-associated α-synuclein gene mutations precede central nervous system changes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 1633–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, C.M.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, J.W. Characterization of gastrointestinal disorders in patients with parkinsonian syndromes. Park. Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, V.D.; Quigley, E.M.; Sullivan, A.M.; O’Keeffe, G.W.; O’Mahony, S.M. Microbiota-gut-brain signalling in Parkinson’s disease: Implications for non-motor symptoms. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’dOnovan, S.M.; Crowley, E.K.; Brown, J.R.; O’sUllivan, O.; O’lEary, O.F.; Timmons, S.; Nolan, Y.M.; Clarke, D.J.; Hyland, N.P.; Joyce, S.A.; et al. Nigral overexpression of α-synuclein in a rat Parkinson’s disease model indicates alterations in the enteric nervous system and the gut microbiome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020, 32, e13726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, C.; Kassubek, J.; Jost, W.H. Management of Pain in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2020, 10, S37–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietdijk, C.D.; Perez-Pardo, P.; Garssen, J.; van Wezel, R.J.A.; Kraneveld, A.D. Exploring Braak’s Hypothesis of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiwaki, H.; Ito, M.; Ishida, T.; Hamaguchi, T.; Maeda, T.; Kashihara, K.; Tsuboi, Y.; Ueyama, J.; Shimamura, T.; Mori, H.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Gut Dysbiosis in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1626–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Yue, Y.; He, T.; Huang, C.; Qu, B.; Lv, W.; Lai, H.-Y. The Association Between the Gut Microbiota and Parkinson’s Disease, a Meta-Analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 636545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tong, Q.; Ma, S.-R.; Zhao, Z.-X.; Pan, L.-B.; Cong, L.; Han, P.; Peng, R.; Yu, H.; Lin, Y.; et al. Oral berberine improves brain dopa/dopamine levels to ameliorate Parkinson’s disease by regulating gut microbiota. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Xu, H.; Luo, Q.; He, J.; Li, M.; Chen, H.; Tang, W.; Nie, Y.; Zhou, Y. Fecal microbiota transplantation to treat Parkinson’s disease with constipation: A case report. Medicine 2019, 98, e16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, X.Y.; Yao, X.H.; Xu, L.J.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Zhang, L.P.; Liu, Y.; Pei, S.; Zhou, C. Evaluation of fecal microbiota transplantation in Parkinson’s disease patients with constipation. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-F.; Zhu, Y.-L.; Zhou, Z.-L.; Jia, X.-B.; Xu, Y.-D.; Yang, Q.; Cui, C.; Shen, Y.-Q. Neuroprotective effects of fecal microbiota transplantation on MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mice: Gut microbiota, glial reaction and TLR4/TNF-α signaling pathway. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 70, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.A.; Rosen, C.J. Parkinson’s disease and osteoporosis: Basic and clinical implications. Expert. Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 15, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, D. Modulation of bone remodeling by the gut microbiota: A new therapy for osteoporosis. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Berge, N.; Ferreira, N.; Gram, H.; Mikkelsen, T.W.; Alstrup, A.K.O.; Casadei, N.; Tsung-Pin, P.; Riess, O.; Nyengaard, J.R.; Tamgüney, G.; et al. Evidence for bidirectional and trans-synaptic parasympathetic and sympathetic propagation of alpha-synuclein in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 138, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, G. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2016, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, I.; Corrigan, F.; Zhai, G.; Zhou, X.F.; Bobrovskaya, L. Lipopolysaccharide animal models of Parkinson’s disease: Recent progress and relevance to clinical disease. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 4, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manole, E.; Dumitrescu, L.; Niculițe, C.; Popescu, B.; Ceafalan, L. Potential roles of functional bacterial amyloid proteins, bacterial biosurfactants and other putative gut microbiota products in the etiopathogeny of Parkinson’s Disease. BIOCELL 2021, 45, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, C.; Lim, Y.; Lim, H.; Ahn, T.B. Plasma Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J.; Rim, J.H.; Ji, D.; Lee, S.; Yoo, H.S.; Jung, J.H.; Baik, K.; Choi, Y.; Ye, B.S.; Sohn, Y.H.; et al. Gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide as a biomarker in early Parkinson’s disease. Nutrition 2021, 83, 111090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Ito, M.; Hamaguchi, T.; Mori, H.; Takeda, Y.; Baba, R.; Watanabe, T.; Kurokawa, K.; Asakawa, S.; Hirayama, M.; et al. Quantification of hydrogen production by intestinal bacteria that are specifically dysregulated in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, M.; Kim, C.S.; Shon, W.J.; Lee, Y.K.; Choi, E.Y.; Shin, D.M. Hydrogen-rich water reduces inflammatory responses and prevents apoptosis of peripheral blood cells in healthy adults: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoritaka, A.; Takanashi, M.; Hirayama, M.; Nakahara, T.; Ohta, S.; Hattori, N. Pilot study of H2 therapy in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]