Multi-Omics Analysis of the Potential Mechanisms of Skin Albinism in Edangered Percocypris pingi: Abnormal Ubiquitination and Calcium Signal Inhibition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Fish

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Histological Analysis

2.3.1. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

2.3.2. Fontana–Masson Staining

2.3.3. Immunohistochemistry

2.4. RNA Isolation and Qualification

2.5. Transcriptomic Profiling

2.5.1. Library Construction and Sequencing

2.5.2. Raw Data QC, De Novo Assembly and Functional Annotation

2.5.3. Gene Expression Quantification and Normalization

2.5.4. Differential Expression and Enrichment Analysis

2.6. Proteomic Profiling

2.6.1. Sample Processing and Mass Spectrometry Acquisition

2.6.2. Protein Identification, Quantification, and Functional Classification

2.6.3. Sample Relationship Analysis and Differentially Expressed Proteins (DEPs)

2.6.4. Functional Enrichment Assessment

2.7. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

2.8. Validation via Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Phenotype and H&E Staining

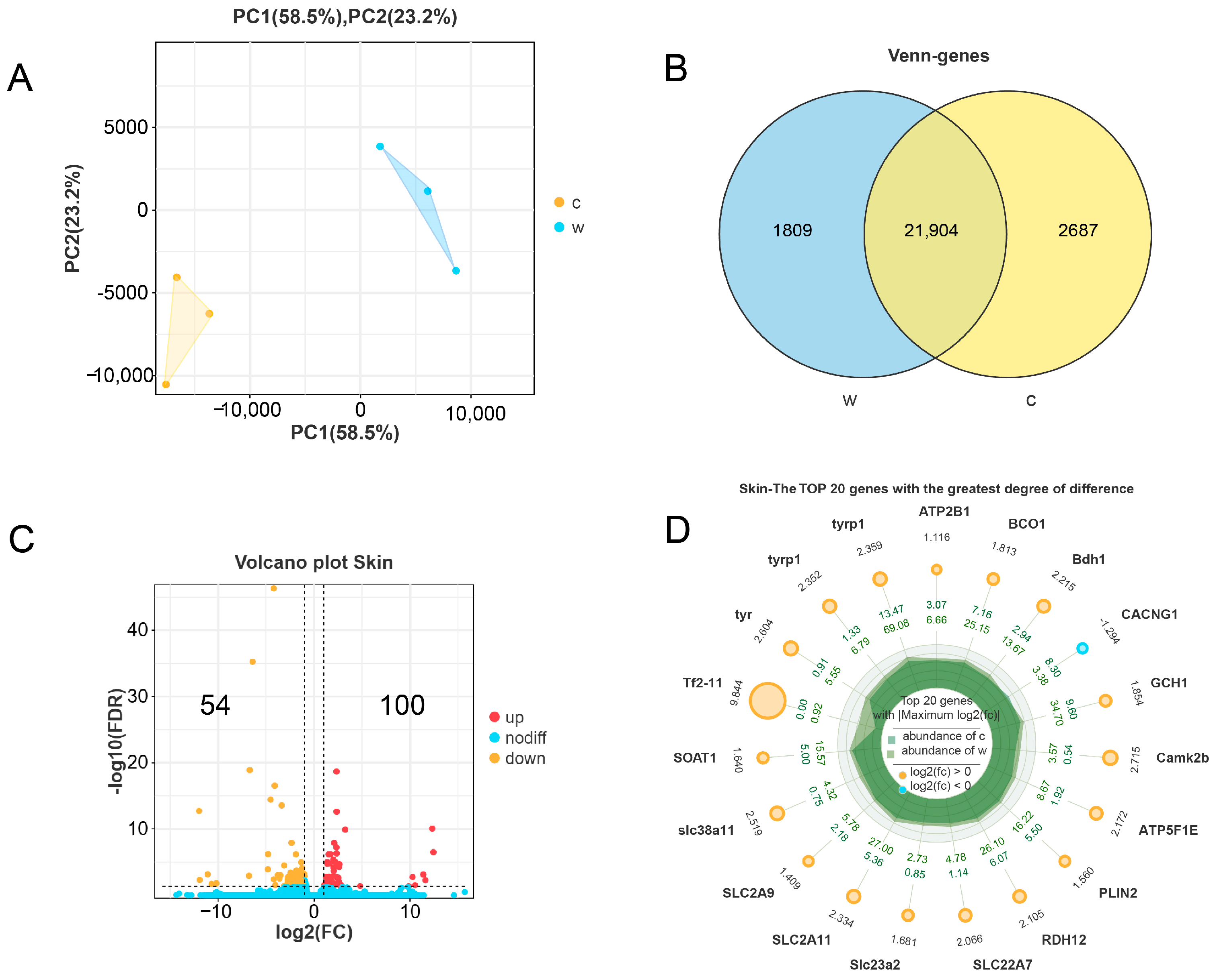

3.2. Transcriptome Differential Analysis and Proteome Differential Analysis

3.3. Analysis of Pathways Related to Melanogenesis

3.4. Analysis of Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteolysis

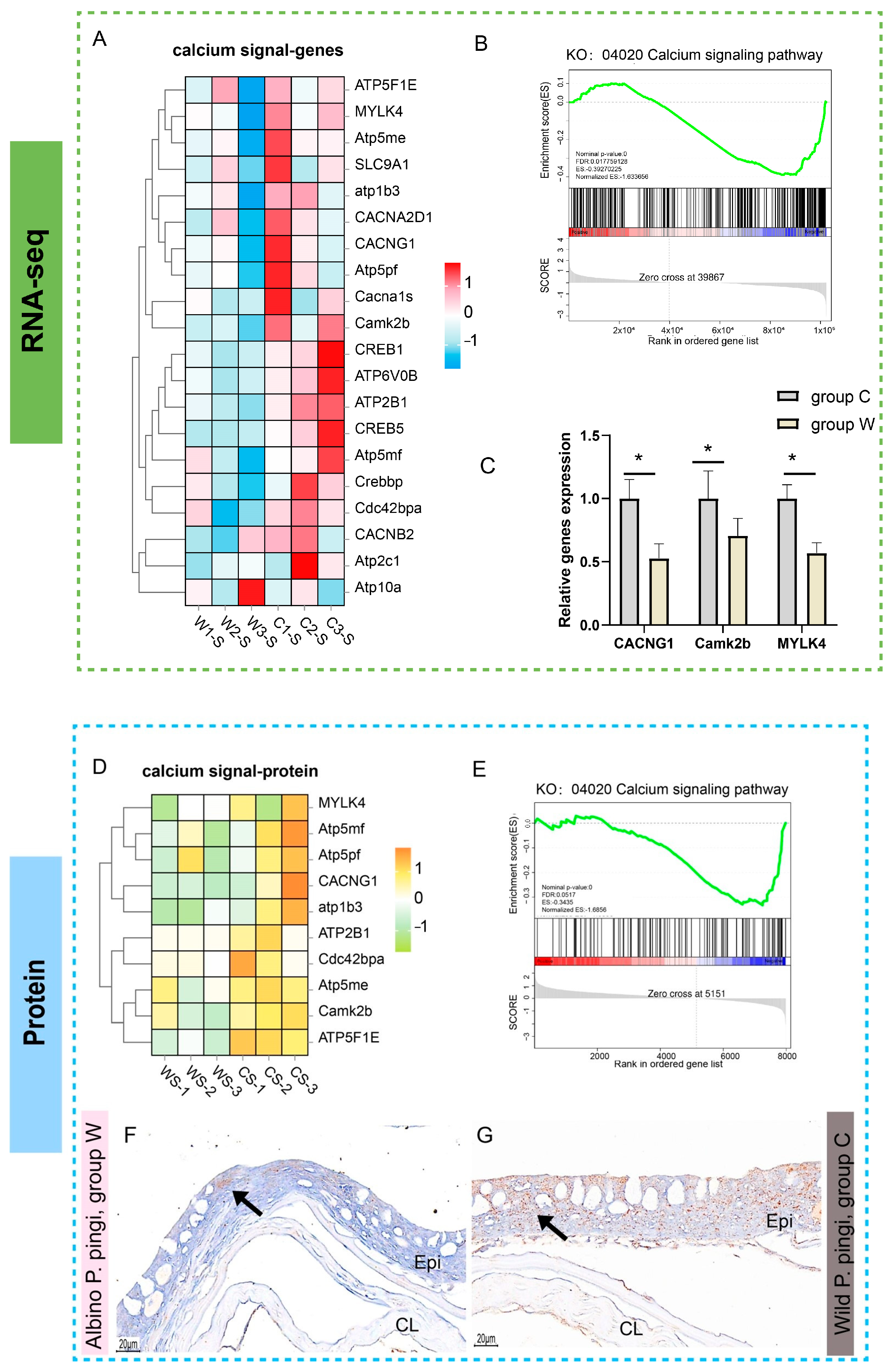

3.5. Analysis of Calcium Signaling Pathways

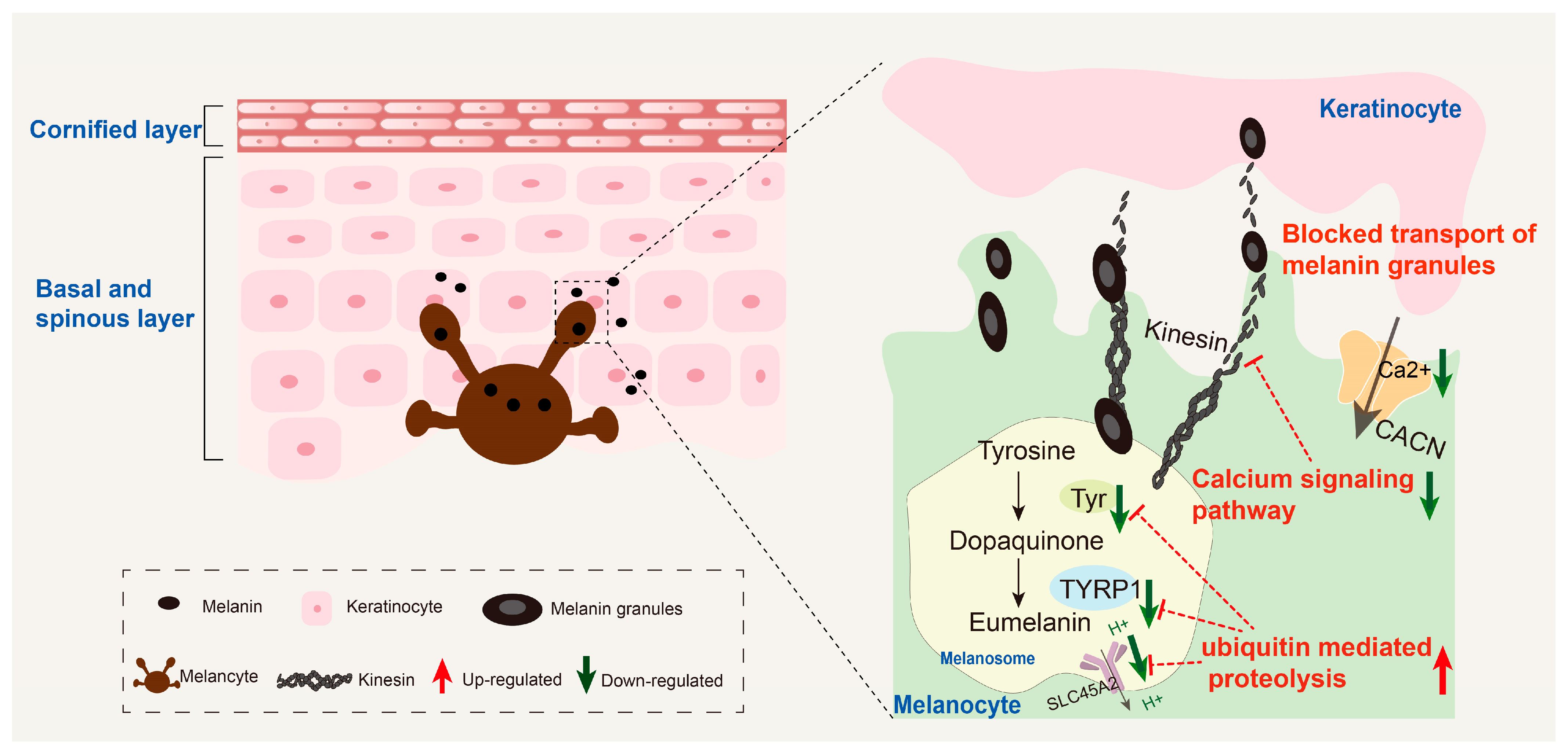

3.6. Potential Regulatory Molecular Networks

4. Discussion

4.1. The Uncoupling Phenomenon of TYR/TYRP1 at the Transcription-Translation Level

4.2. Excessive Activation of the UPS

4.3. Inhibition of the Calcium Signaling Pathway

4.4. Limitations of This Study and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riley, P.A. Melanin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 1997, 29, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delevoye, C. Melanin transfer: The keratinocytes are more than gluttons. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 877–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Zippin, J.H.; Ito, S. Chemical and biochemical control of skin pigmentation with special emphasis on mixed melanogenesis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021, 34, 730–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S. An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 2440–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, W.; Gu, Z.; Wang, L.; Guo, L.; Ma, S.; Li, C.; Sun, J.; Han, B.; Chang, J. Recent advances and progress on melanin: From source to application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okulicz, J.F.; Shah, R.S.; Schwartz, R.A.; Janniger, C.K. Oculocutaneous albinism. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2003, 17, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Zhu, W.; Jiang, J. Albinism in the largest extant amphibian: A metabolic, endocrine, or immune problem? Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1053732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Ichihashi, M.; Hearing, V.J. Role of the ubiquitin proteasome system in regulating skin pigmentation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 4428–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, F.; Simoes, S.; Raposo, G. The ocular albinism type 1 (OA1) GPCR is ubiquitinated and its traffic requires endosomal sorting complex responsible for transport (ESCRT) function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11906–11911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, T.; Xu, N.; Li, J.; Zhao, M.; Li, X.; Huang, L. Conditional loss of Ube3d in the retinal pigment epithelium accelerates age-associated alterations in the retina of mice. J. Pathol. 2023, 261, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bento-Lopes, L.; Cabaço, L.C.; Charneca, J.; Neto, M.V.; Seabra, M.C.; Barral, D.C. Melanin’s journey from melanocytes to keratinocytes: Uncovering the molecular mechanisms of melanin transfer and processing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M. Rab GTPases: Key players in melanosome biogenesis, transport, and transfer. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021, 34, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Cui, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhou, J.; Cui, R. Melanosome transport and regulation in development and disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 219, 107707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Z. Red list of China’s vertebrates. Biol. Div. 2016, 24, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Li, C.; Gao, K.; Zheng, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Yang, D.; et al. The whole chromosome-level genome provides resources and insights into the endangered fish Percocypris pingi evolution and conservation. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, A.T.; Wolfe, D. Tissue processing and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1180, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Xia, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Huang, J.; et al. Increased melanin induces aberrant keratinocyte-melanocyte-basal-fibroblast cell communication and fibrogenesis by inducing iron overload and ferroptosis resistance in keloids. Cell Commun. Signal. 2025, 23, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.A. The Benjamini-Hochberg method in the case of discrete test statistics. Int. J. Biostat. 2007, 3, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Jiang, N.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zeng, L.; Zhong, Q.; Li, Z.; Fan, Y. Characterization of reference genes for qRT-PCR normalization in rice-field eel (Monopterus albus) to assess differences in embryonic developmental stages, the early development of immune organs, and cells infected with rhabdovirus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 120, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Liu, Z.; Huang, J.; Kang, Y.; Wang, J. Evaluation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis of messenger RNAs and microRNAs in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss under heat stress. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 95, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 (-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Namasivayam, V. Skin whitening agents: Medicinal chemistry perspective of tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, S.; Kang, D.; Lee, S.; Ikram, M.; Park, C.; Park, Y.; Yoon, S.; Chun, P.; Moon, H.R. Synthesis of cinnamic amide derivatives and their anti-melanogenic effect in α-MSH-stimulated B16F10 melanoma cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 161, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Harashima, A.; Kato, K.; Gu, L.; Motomura, Y.; Otsuka, R.; Maeda, K. Degradation of Tyrosinase by Melanosomal pH Change and a New Mechanism of Whitening with Propylparaben. Cosmetics 2017, 4, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancans, J.; Tobin, D.J.; Hoogduijn, M.J.; Smit, N.P.; Wakamatsu, K.; Thody, A.J. Melanosomal pH controls rate of melanogenesis, eumelanin/phaeomelanin ratio and melanosome maturation in melanocytes and melanoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2001, 268, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, B.B.; Spaulding, D.T.; Smith, D.R. Regulation of the catalytic activity of preexisting tyrosinase in black and Caucasian human melanocyte cell cultures. Exp. Cell Res. 2001, 262, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R.; Spaulding, D.T.; Glenn, H.M.; Fuller, B.B. The relationship between Na(+)/H(+) exchanger expression and tyrosinase activity in human melanocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 2004, 298, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, C.M.; Schwarz, H.; Mueller, K.P.; Mongera, A.; Konantz, M.; Neuhauss, S.C.; Nüsslein-Volhard, C.; Geisler, R. Slc45a2 and V-ATPase are regulators of melanosomal pH homeostasis in zebrafish, providing a mechanism for human pigment evolution and disease. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2013, 26, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, B.H.; Bhin, J.; Yang, S.H.; Shin, M.; Nam, Y.J.; Choi, D.H.; Shin, D.W.; Lee, A.Y.; Hwang, D.; Cho, E.G.; et al. Membrane-associated transporter protein (matp) regulates melanosomal ph and influences tyrosinase activity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damgaard, R.B. The ubiquitin system: From cell signalling to disease biology and new therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, K. Growth and progression of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers regulated by ubiquitination. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010, 23, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, D.; Chen, K.S. UBE3A regulates MC1R expression: A link to hypopigmentation in Angelman syndrome. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011, 24, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudrier, E. Myosins in melanocytes: To move or not to move? Pigment Cell Res. 2007, 20, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano-Pellicena, I.; Morrison, C.G.; Bell, M.; O’Connor, C.; Tobin, D.J. Melanin distribution in human skin: Influence of cytoskeletal, polarity, and centrosome-related machinery of stratum basale keratinocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Schafer, N.P.; Bueno, C.; Song, S.S.; Hudmon, A.; Wolynes, P.G.; Waxham, M.N.; Cheung, M.S. Assemblies of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II with actin and their dynamic regulation by calmodulin in dendritic spines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 18937–18942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehne, F.; Pokrant, T.; Parbin, S.; Salinas, G.; Großhans, J.; Rust, K.; Faix, J.; Bogdan, S. Calcium bursts allow rapid reorganization of EFhD2/Swip-1 cross-linked actin networks in epithelial wound closure. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2492–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Façanha, A.L.; Appelgren, H.; Tabish, M.; Okorokov, L.; Ekwall, K. The endoplasmic reticulum cation P-type ATPase Cta4p is required for control of cell shape and microtubule dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 157, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecna, A.; Frischknecht, R.; Kinter, J.; Ludwig, A.; Steuble, M.; Meskenaite, V.; Indermühle, M.; Engel, M.; Cen, C.; Mateos, J.M.; et al. Sonderegger. Calsyntenin-1 docks vesicular cargo to kinesin-1. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 3651–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffey, J.A.; Edgecombe, M.; Mac Neil, S. Calcium plays a complex role in the regulation of melanogenesis in murine B16 melanoma cells. Pigment Cell Res. 1993, 6, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, M.; Hearing, V.J. The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Wu, X.; Zou, Q.; Lai, J.; Ni, L.; Deng, Y.; Feng, Y.; Song, M.; Li, P.; Du, J.; et al. Multi-Omics Analysis of the Potential Mechanisms of Skin Albinism in Edangered Percocypris pingi: Abnormal Ubiquitination and Calcium Signal Inhibition. Cells 2025, 14, 1684. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211684

Liu S, Wu X, Zou Q, Lai J, Ni L, Deng Y, Feng Y, Song M, Li P, Du J, et al. Multi-Omics Analysis of the Potential Mechanisms of Skin Albinism in Edangered Percocypris pingi: Abnormal Ubiquitination and Calcium Signal Inhibition. Cells. 2025; 14(21):1684. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211684

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Senyue, Xiaoyun Wu, Qiaolin Zou, Jiansheng Lai, Luyun Ni, Yongqiang Deng, Yang Feng, Mingjiang Song, Pengcheng Li, Jun Du, and et al. 2025. "Multi-Omics Analysis of the Potential Mechanisms of Skin Albinism in Edangered Percocypris pingi: Abnormal Ubiquitination and Calcium Signal Inhibition" Cells 14, no. 21: 1684. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211684

APA StyleLiu, S., Wu, X., Zou, Q., Lai, J., Ni, L., Deng, Y., Feng, Y., Song, M., Li, P., Du, J., Li, Q., & Liu, Y. (2025). Multi-Omics Analysis of the Potential Mechanisms of Skin Albinism in Edangered Percocypris pingi: Abnormal Ubiquitination and Calcium Signal Inhibition. Cells, 14(21), 1684. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211684