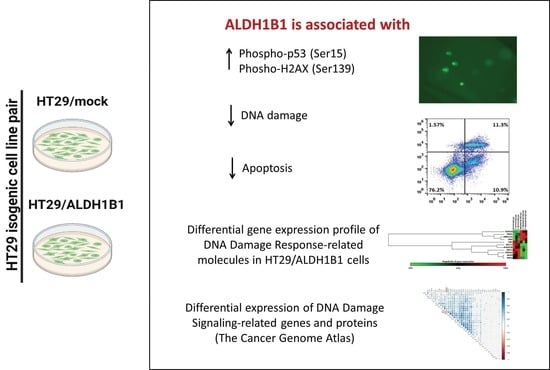

Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1B1 Is Implicated in DNA Damage Response in Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Protein Extraction, Cell Lysates Preparation and Western Immunoblotting

2.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.4.1. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Total p53 Expression

2.4.2. Annexin V—Propidium Iodide (PI) Double Staining

2.5. Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis Assay (Comet Assay)

2.6. RT2 ProfilerTM PCR Array for DNA Damage Signaling Pathway

2.7. Data Acquisition and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

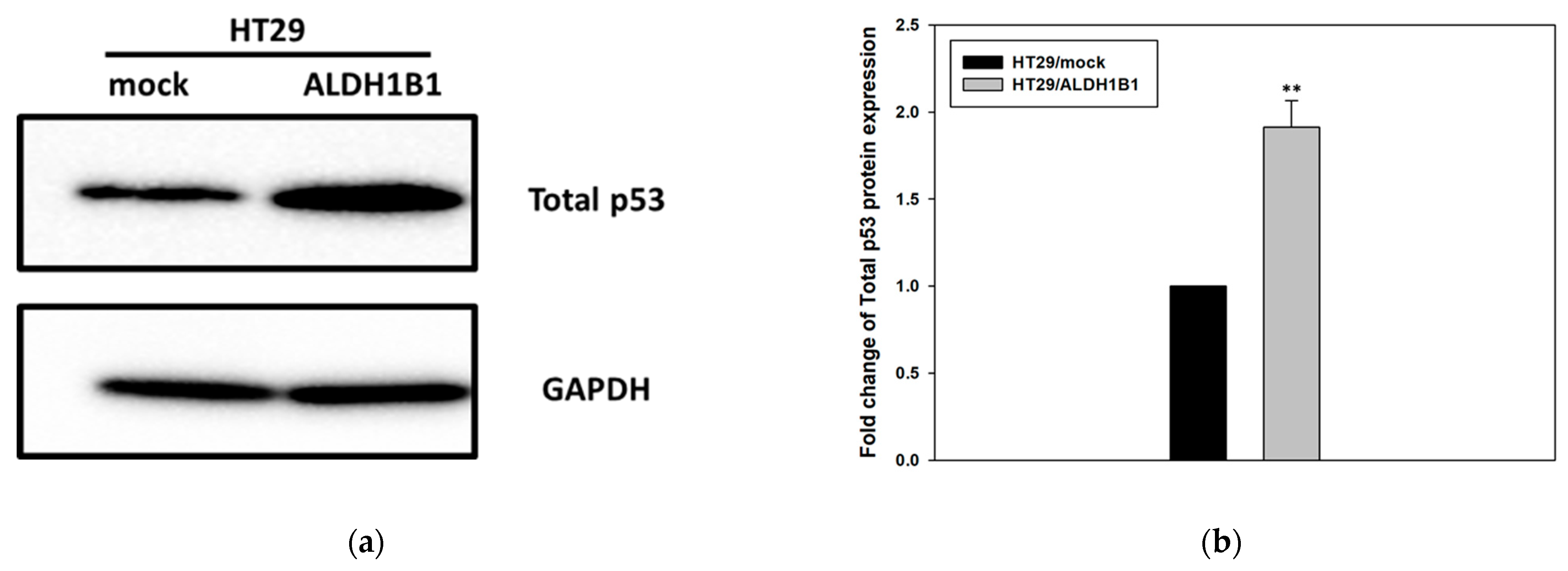

3.1. ALDH1B1 Expression Leads to Increased Constitutive Phosphorylation of p53 (at ser15) in HT29 Cells

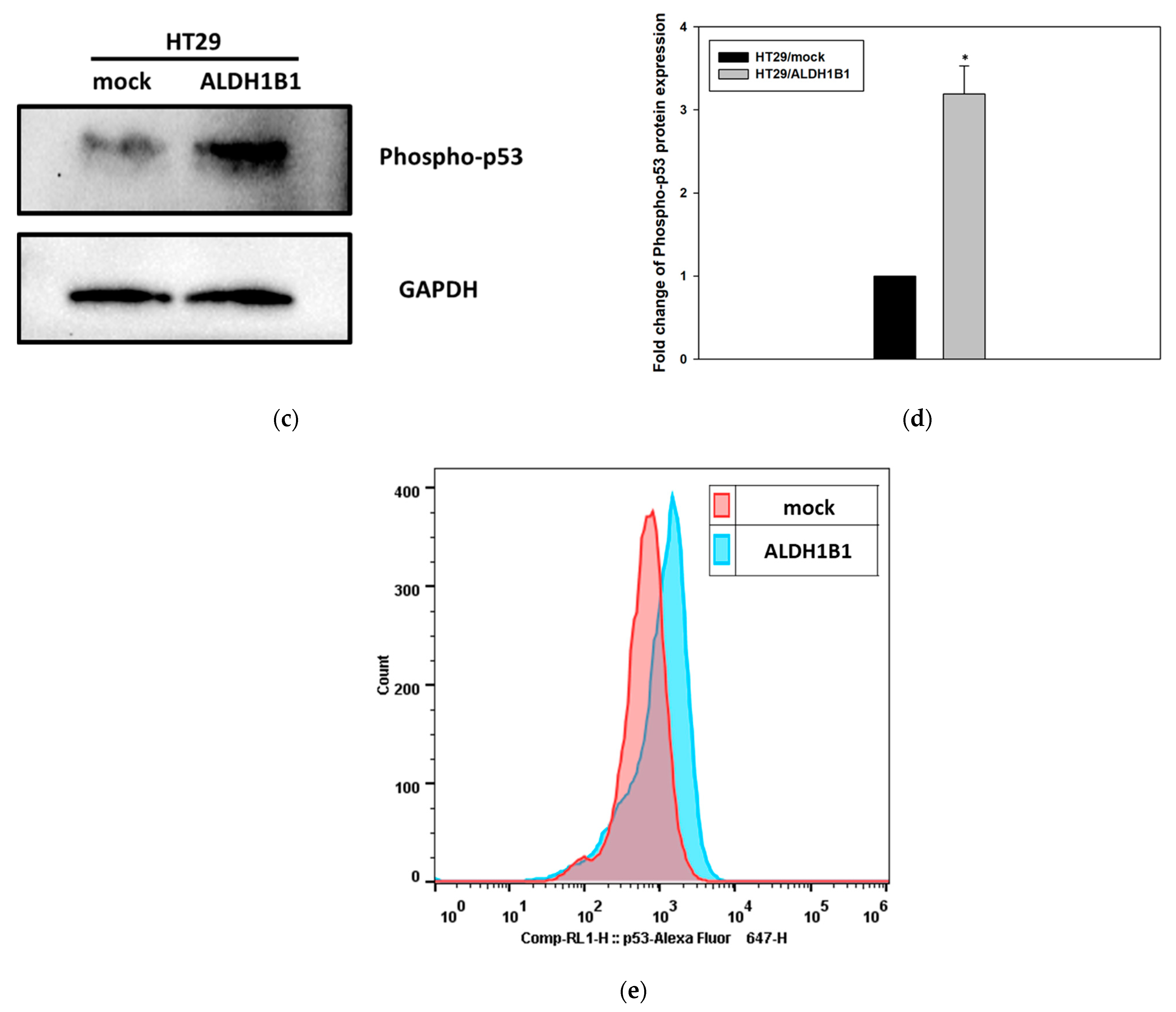

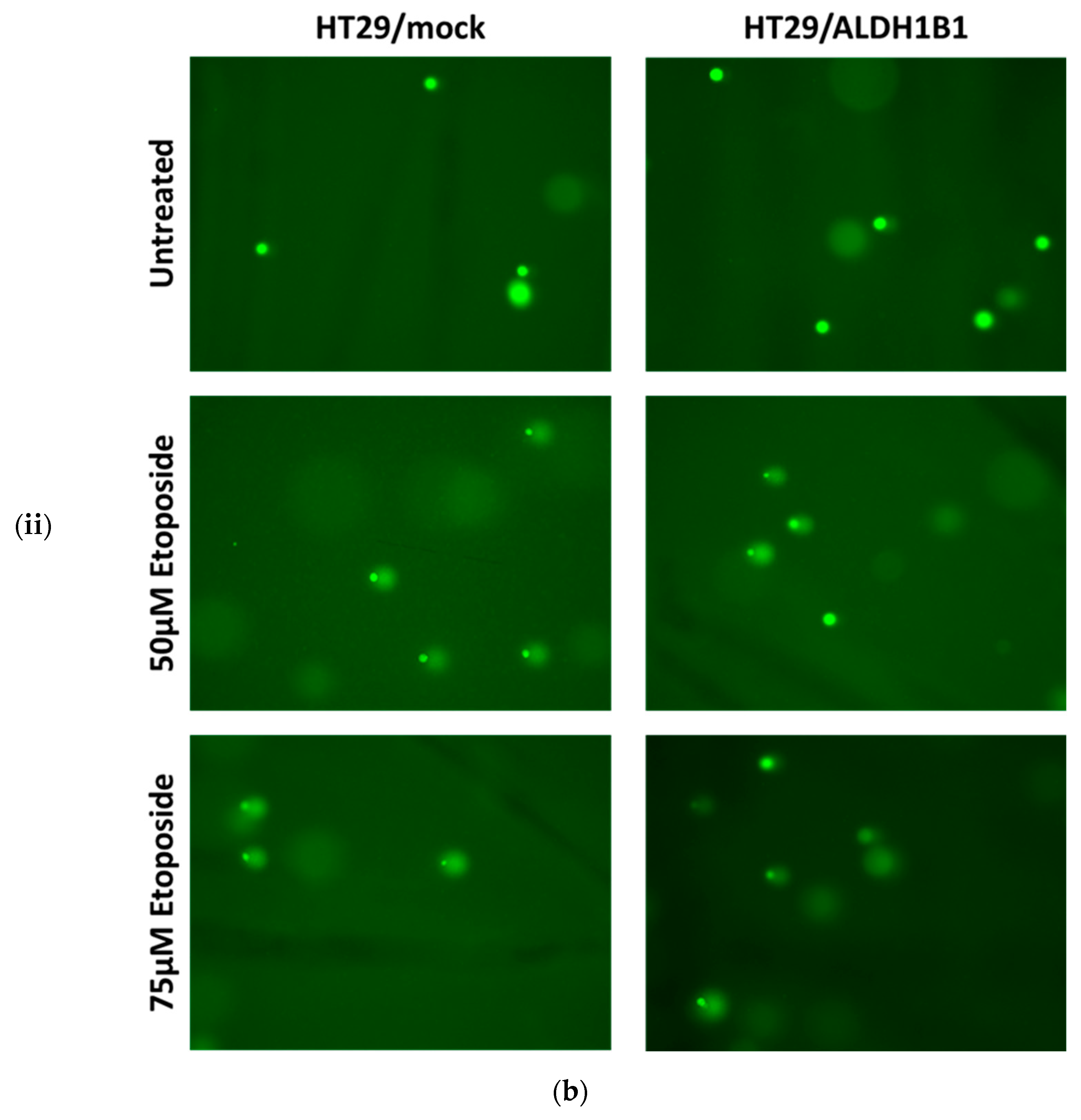

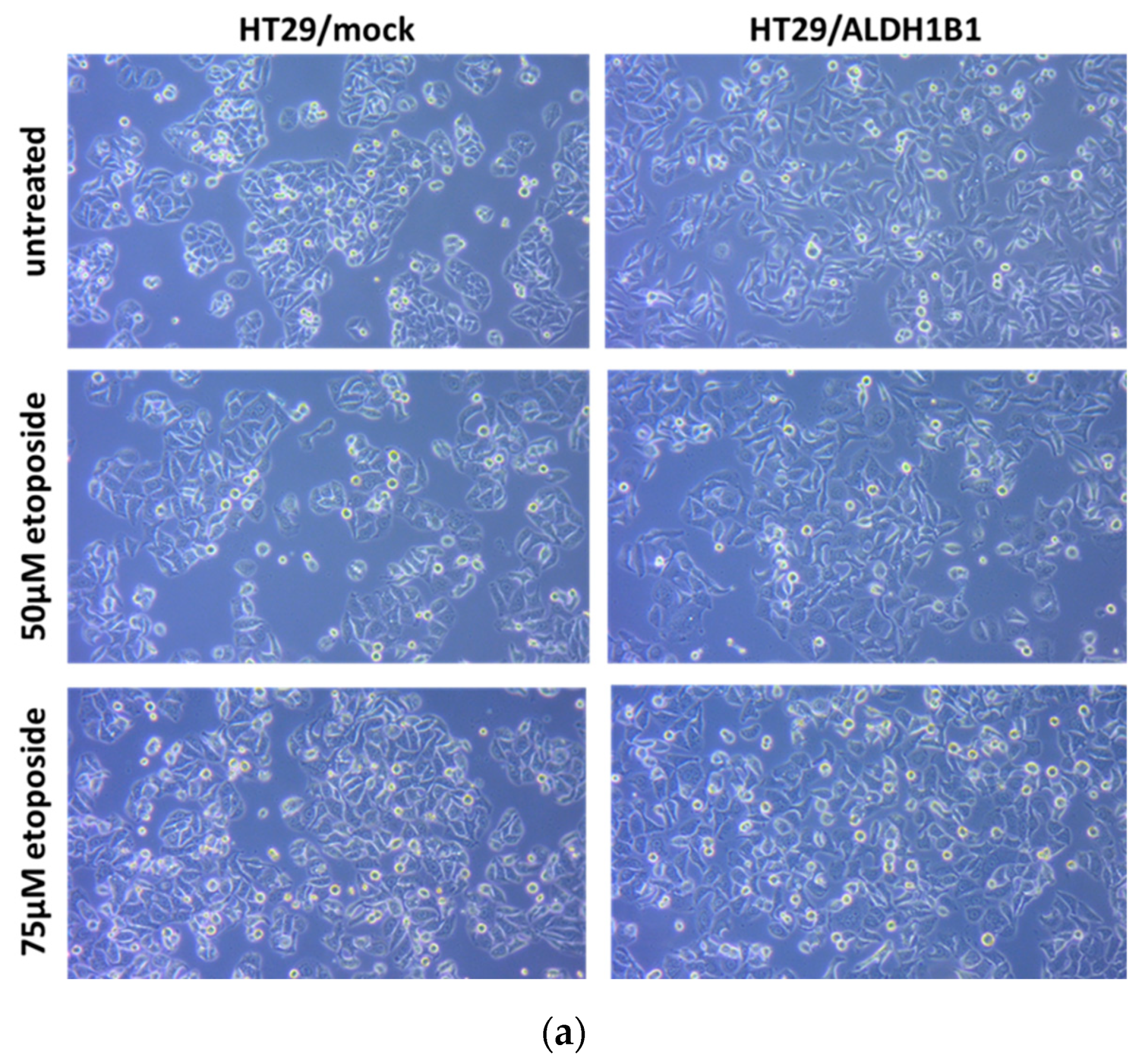

3.2. ALDH1B1 Protects HT29 Cells from Etoposide-Induced DNA Damage

3.3. ALDH1B1 Protects HT29 Cells from Etoposide-Induced Apoptosis

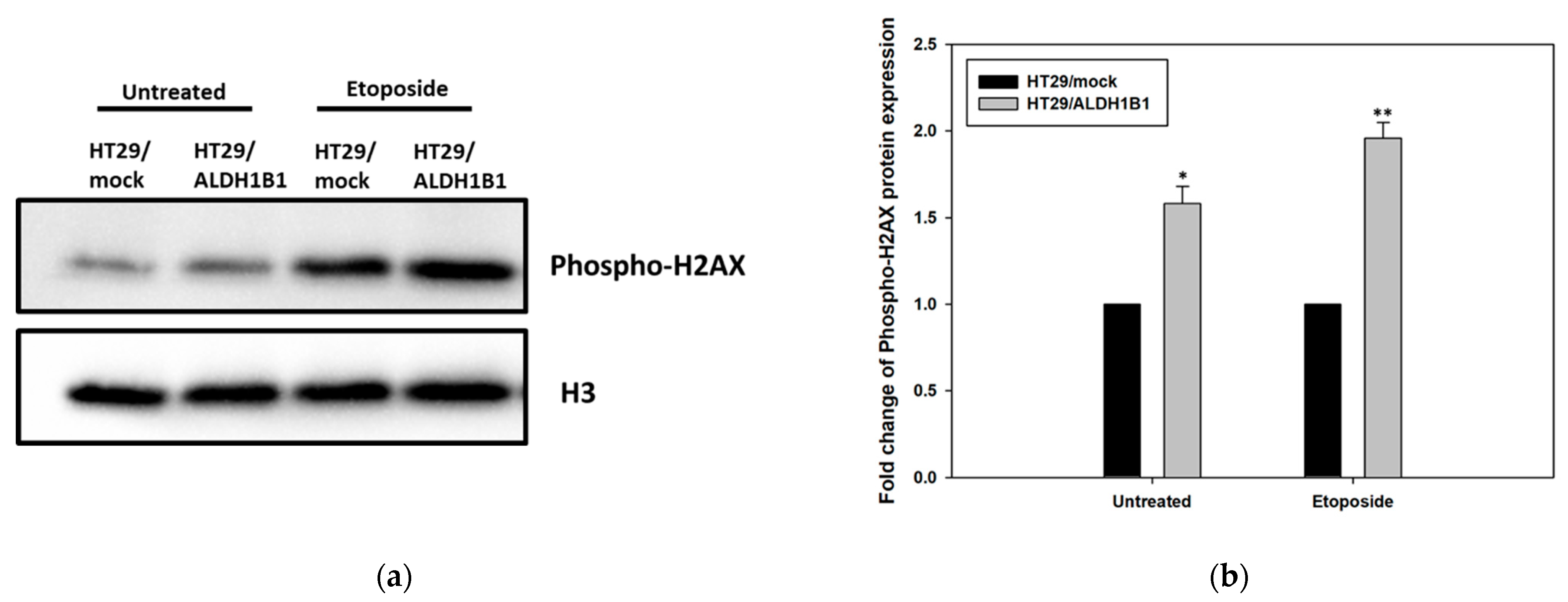

3.4. ALDH1B1 Overexpression Leads to Increased Phosphorylation of H2AX (ser139) in HT29 Cells

3.5. HT29/ALDH1B1 Cells Exhibit the Differential Gene Expression Profile of DDR-Related Proteins Compared to HT29/Mock Cells

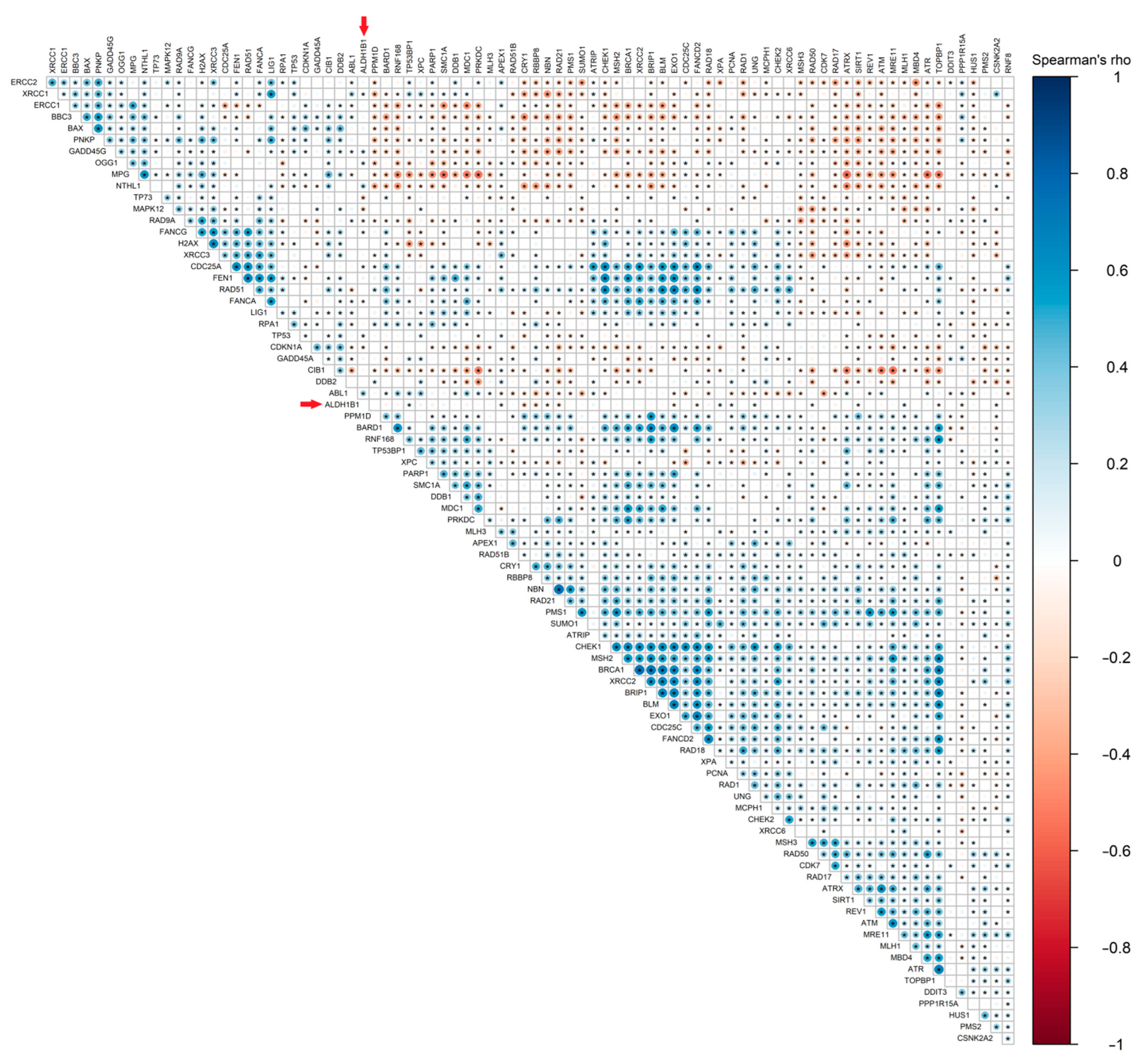

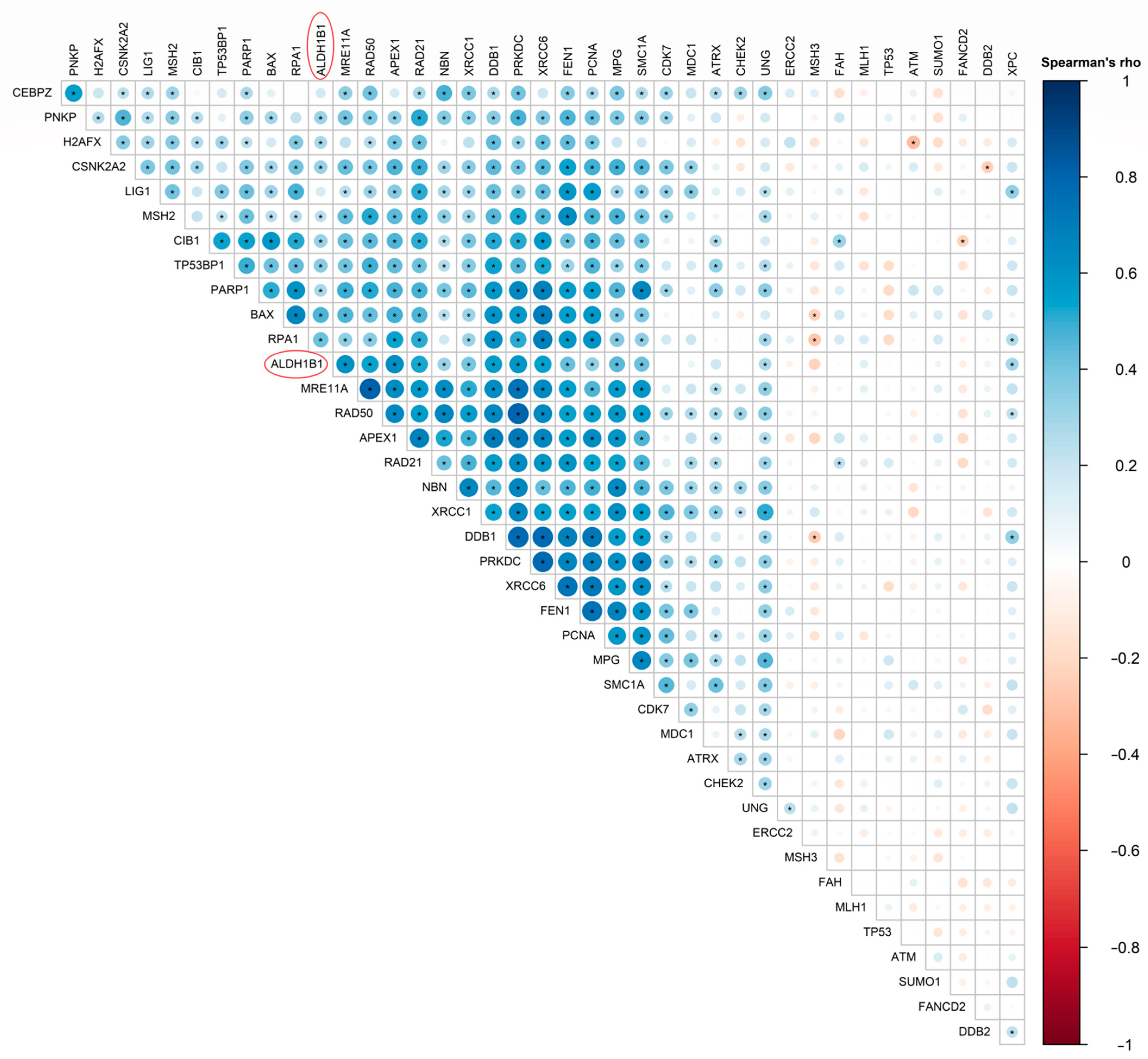

3.6. ALDH1B1 Is Associated with DDS-Related Genes and Proteins in 531 and 77 Colon and Rectal Adenocarcinoma Patient Samples, Respectively

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marchitti, S.A.; Brocker, C.; Stagos, D.; Vasiliou, V. Non-P450 aldehyde oxidizing enzymes: The aldehyde dehydrogenase superfamily. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2008, 4, 697–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsochantaridis, I.; Roupas, A.; Voulgaridou, G.-P.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Koukourakis, M.I.; Panayiotidis, M.I.; Pappa, A. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1B1 Is Associated with Altered Cell Morphology, Proliferation, Migration and Chemosensitivity in Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliou, V.; Thompson, D.C.; Smith, C.; Fujita, M.; Chen, Y. Aldehyde dehydrogenases: From eye crystallins to metabolic disease and cancer stem cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2013, 202, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, B.C.; Holmes, R.S.; Backos, D.S.; Reigan, P.; Thompson, D.C.; Vasiliou, V. Comparative genomics, molecular evolution and computational modeling of ALDH1B1 and ALDH2. Chem. -Biol. Interact. 2013, 202, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, C.K.; Wang, X.K.; Liao, X.W.; Han, C.; Yu, T.; Qin, W.; Zhu, G.; Su, H.; Yu, L.; Liu, X.; et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) isoform expression and potential clinical implications in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, M.; Serafimidis, I.; Arnes, L.; Sussel, L.; Singh, S.; Vasiliou, V.; Gavalas, A. ALDH1B1 is a potential stem/progenitor marker for multiple pancreas progenitor pools. Dev. Biol. 2013, 374, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiou, V.; Ninou, E.; Alexopoulou, D.; Stertmann, J.; Müller, A.; Dahl, A.; Solimena, M.; Speier, S.; Serafimidis, I.; Gavalas, A. Aldehyde dehydrogenase activity is necessary for beta cell development and functionality in mice. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Arcaroli, J.; Chen, Y.; Thompson, D.C.; Messersmith, W.; Jimeno, A.; Vasiliou, V. ALDH1B1 Is Crucial for Colon Tumorigenesis by Modulating Wnt/β-Catenin, Notch and PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathways. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, A.; Arcaroli, J.; Chen, Y.; Gasparetto, M.; Neumeister, V.; Thompson, D.C.; Singh, S.; Smith, C.; Messersmith, W.; Vasiliou, V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1B1: A novel immunohistological marker for colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 1537–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Arcaroli, J.J.; Orlicky, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Messersmith, W.A.; Bagby, S.; Purkey, A.; Quackenbush, K.S.; Thompson, D.C.; Vasiliou, V. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1B1 as a Modulator of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 2016, 45, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameishvili, E.; Serafimidis, I.; Iwaszkiewicz, S.; Lesche, M.; Reinhardtd, S.; Bölicke, N.; Büttner, M.; Stellas, D.; Papadimitropoulou, A.; Szabolcs, M.; et al. Aldh1b1 expression defines progenitor cells in the adult pancreas and is required for Kras-induced pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 20679–20688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Orlicky, D.J.; Matsumoto, A.; Singh, S.; Thompson, D.C.; Vasiliou, V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1B1 (ALDH1B1) is a potential biomarker for human colon cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 405, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, R.C.; Mullinax, J.E.; Ray, S.; Raiji, M.T.; Schaub, N.; Xin, H.W.; Koizumi, T.; Steinberg, S.M.; Anderson, A.; Wiegand, G.; et al. A pilot study assessing the potential role of non-CD133 colorectal cancer stem cells as biomarkers. J. Cancer 2012, 3, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, D.; Li, X.; Jia, S.; Qi, S.; Huang, J. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1B1 is a potential marker of colorectal tumors. Histol. Histopathol. 2021, 36, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E.; et al. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, pl1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, P.L.; Banáth, J.P. The comet assay: A method to measure DNA damage in individual cells. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotidis, M.; Tsolas, O.; Galaris, D. Glucose oxidase-produced H2O2 induces Ca2+-dependent DNA damage in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaridou, G.P.; Tsochantaridis, I.; Tolkas, C.; Franco, R.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I.; Pappa, A. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 3A1 confers oxidative stress resistance accompanied by altered DNA damage response in human corneal epithelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 150, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Traganos, F.; Darzynkiewicz, Z. Phosphorylation of p53 on Ser15 during cell cycle caused by Topo I and Topo II inhibitors in relation to ATM and Chk2 activation. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 3048–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamil, S.; Lam, I.; Majd, M.; Tsai, S.-H.; Duronio, V. Etoposide induces cell death via mitochondrial-dependent actions of p53. Cancer Cell Int. 2015, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mah, L.J.; El-Osta, A.; Karagiannis, T.C. gammaH2AX: A sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia 2010, 24, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, Z.; Lambourne, S.R.; Curry, B.J.; Hall, S.E.; Aitken, R.J. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Plays a Pivotal Role in the Maintenance of Stallion Sperm Motility1. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 94, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagos, D.; Chen, Y.; Brocker, C.; Donald, E.; Jackson, B.C.; Orlicky, D.J.; Thompson, D.C.; Vasiliou, V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1B1: Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel mitochondrial acetaldehyde-metabolizing enzyme. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010, 38, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chen, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Orlicky, D.J.; Dong, H.; Thompson, D.C.; Vasiliou, V. ALDH1B1 links alcohol consumption and diabetes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 463, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; He, Y.; Cai, Q.; Gao, S.; Yao, W.; Liu, Z.; Tian, Z.; Han, Q.; Wang, W.; et al. Upregulation of ALDH1B1 promotes tumor progression in osteosarcoma. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 2502–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burma, S.; Chen, B.P.; Murphy, M.; Kurimasa, A.; Chen, D.J. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 42462–42467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogakou, E.P.; Pilch, D.R.; Orr, A.H.; Ivanova, V.S.; Bonner, W.M. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 5858–5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, I.S.; Kang, M.H. DNA-PK as an Emerging Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, J.S.; Redon, C.E.; Nakamura, A.J.; Baird, B.J.; Sedelnikova, O.A.; Bonner, W.M. H2AX: Functional roles and potential applications. Chromosoma 2009, 118, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Halicka, H.D.; Huang, X.; Traganos, F.; Darzynkiewicz, Z. Constitutive histone H2AX phosphorylation and ATM activation, the reporters of DNA damage by endogenous oxidants. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 1940–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivashkevich, A.; Redon, C.E.; Nakamura, A.J.; Martin, R.F.; Martin, O.A. Use of the γ-H2AX assay to monitor DNA damage and repair in translational cancer research. Cancer Lett. 2012, 327, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darzynkiewicz, Z.; Traganos, F.; Zhao, H.; Halicka, H.D.; Skommer, J.; Wlodkowic, D. Analysis of individual molecular events of DNA damage response by flow- and image-assisted cytometry. Methods Cell Biol. 2011, 103, 115–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tanaka, T.; Kurose, A.; Traganos, F.; Darzynkiewicz, Z. Constitutive histone H2AX phosphorylation on Ser-139 in cells untreated by genotoxic agents is cell-cycle phase specific and attenuated by scavenging reactive oxygen species. Int. J. Oncol. 2006, 29, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abad, E.; Graifer, D.; Lyakhovich, A. DNA damage response and resistance of cancer stem cells. Cancer Lett. 2020, 474, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.; Webb, B.; Gerson, S.L. CD133+ cells contribute to radioresistance via altered regulation of DNA repair genes in human lung cancer cells. Radiother. Oncol. 2014, 110, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Behbod, F.; Atkinson, R.L.; Landis, M.D.; Kittrell, F.; Edwards, D.; Medina, D.; Tsimelzon, A.; Hilsenbeck, S.; Green, J.E.; et al. Identification of tumor-initiating cells in a p53-null mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 4674–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, P.M.; Fjell, B.; Kravik, K.L.; Haug, T.; Tunheim, S.H.; Reichelt, W.; Beigi, M.; Clausen, O.P.; Galteland, E.; Stokkeet, T. Molecular characterizations of derivatives of HCT116 colorectal cancer cells that are resistant to the chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil. Int. J. Oncol. 2004, 24, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, E.; Mitra, A.; Tripathi, K.; Finan, M.A.; Scalici, J.; McClellan, S.; da Silva, L.M.; Reed, E.; Shevde, L.; Palle, K.; et al. ALDH1A1 Maintains Ovarian Cancer Stem Cell-Like Properties by Altered Regulation of Cell Cycle Checkpoint and DNA Repair Network Signaling. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Weng, X.; Yao, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Lin, R.; Lin, Z. ALDH-1-positive cells exhibited a radioresistant phenotype that was enhanced with hypoxia in cervical cancer. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HT29/Mock | HT29/ALDH1B1 | Statistical Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Fluorescence intensity | 579.5 ± 131.46 | 860.75 ± 118.71 | * |

| Untreated | 50 μΜ Etoposide | 75 μΜ Etoposide | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT29/mock (%) | Live | 83.03 ± 1.88 | 68.43 ± 3.12 | 59.39 ± 3.31 |

| Early apoptotic | 8.32 ± 1.56 | 11.27 ± 2.53 | 12.19 ± 1.38 | |

| Late apoptotic | 7.78 ± 0.93 | 18.3 ± 1.93 | 22.82 ± 0.28 | |

| Dead | 0.87 ± 0.52 | 2.00 ± 1.15 | 5.60 ± 2.24 | |

| HT29/ALDH1B1 (%) | Live | 85.47 ± 0.65 | 75.97 ± 0.40 | 77.1 ± 1.47 |

| Early apoptotic | 8.00 ± 0.54 | 12.03 ± 1.96 | 8.79 ± 0.97 | |

| Late apoptotic | 5.86 ± 0.30 | 11.00 ± 1.28 | 12.31 ± 0.56 | |

| Dead | 0.67 ± 0.62 | 1.00 ± 0.47 | 1.8 ± 0.12 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsochantaridis, I.; Kontopoulos, A.; Voulgaridou, G.-P.; Tsifintaris, M.; Triantafyllou, C.; Pappa, A. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1B1 Is Implicated in DNA Damage Response in Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Cells 2022, 11, 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132017

Tsochantaridis I, Kontopoulos A, Voulgaridou G-P, Tsifintaris M, Triantafyllou C, Pappa A. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1B1 Is Implicated in DNA Damage Response in Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Cells. 2022; 11(13):2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132017

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsochantaridis, Ilias, Alexandros Kontopoulos, Georgia-Persephoni Voulgaridou, Margaritis Tsifintaris, Charisios Triantafyllou, and Aglaia Pappa. 2022. "Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1B1 Is Implicated in DNA Damage Response in Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma" Cells 11, no. 13: 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132017

APA StyleTsochantaridis, I., Kontopoulos, A., Voulgaridou, G.-P., Tsifintaris, M., Triantafyllou, C., & Pappa, A. (2022). Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1B1 Is Implicated in DNA Damage Response in Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Cells, 11(13), 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132017