Cultivation Management Reshapes Soil Profile Configuration and Organic Carbon Sequestration: Evidence from a 45-Year Field Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Profile Description and Soil Sample Collection

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

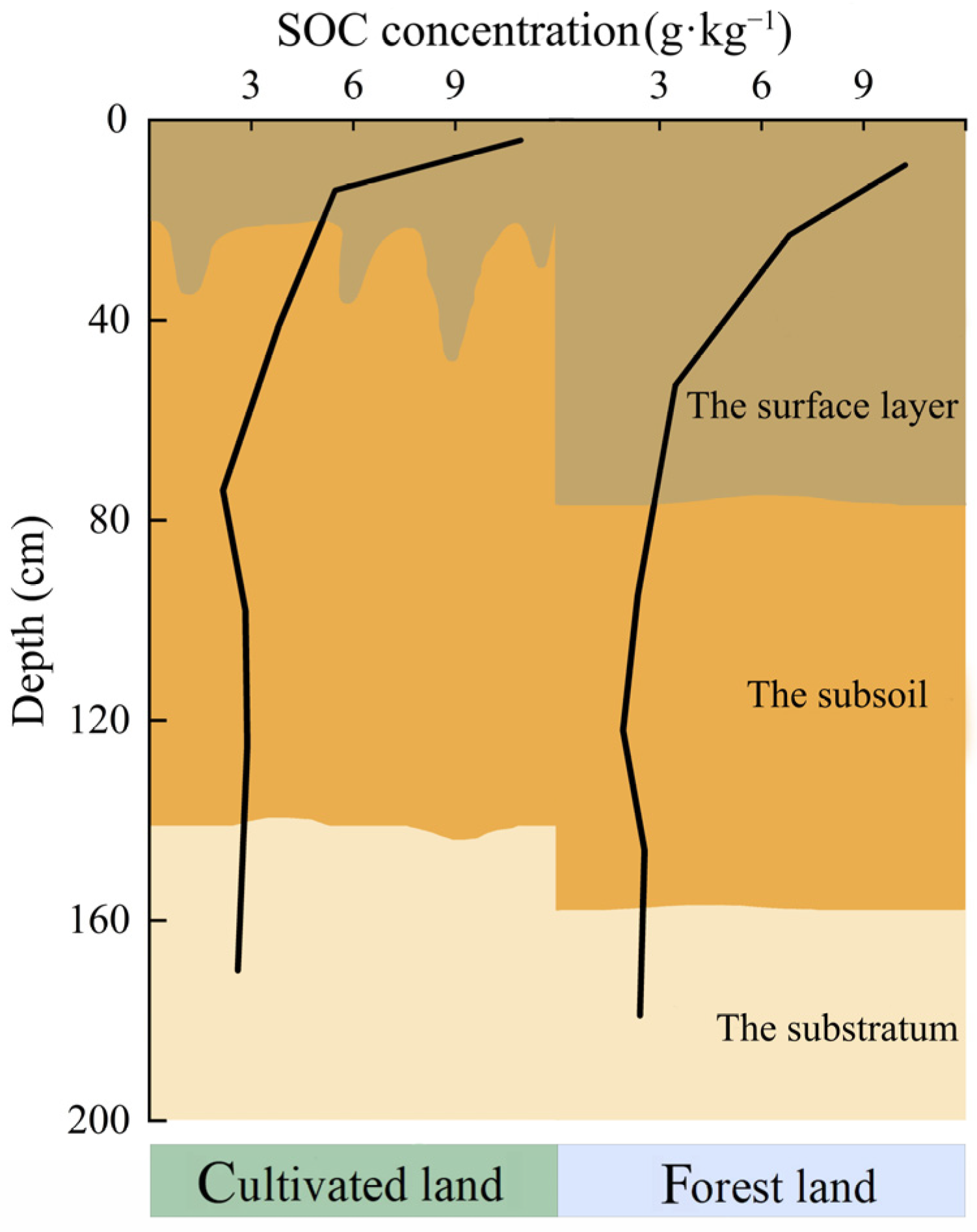

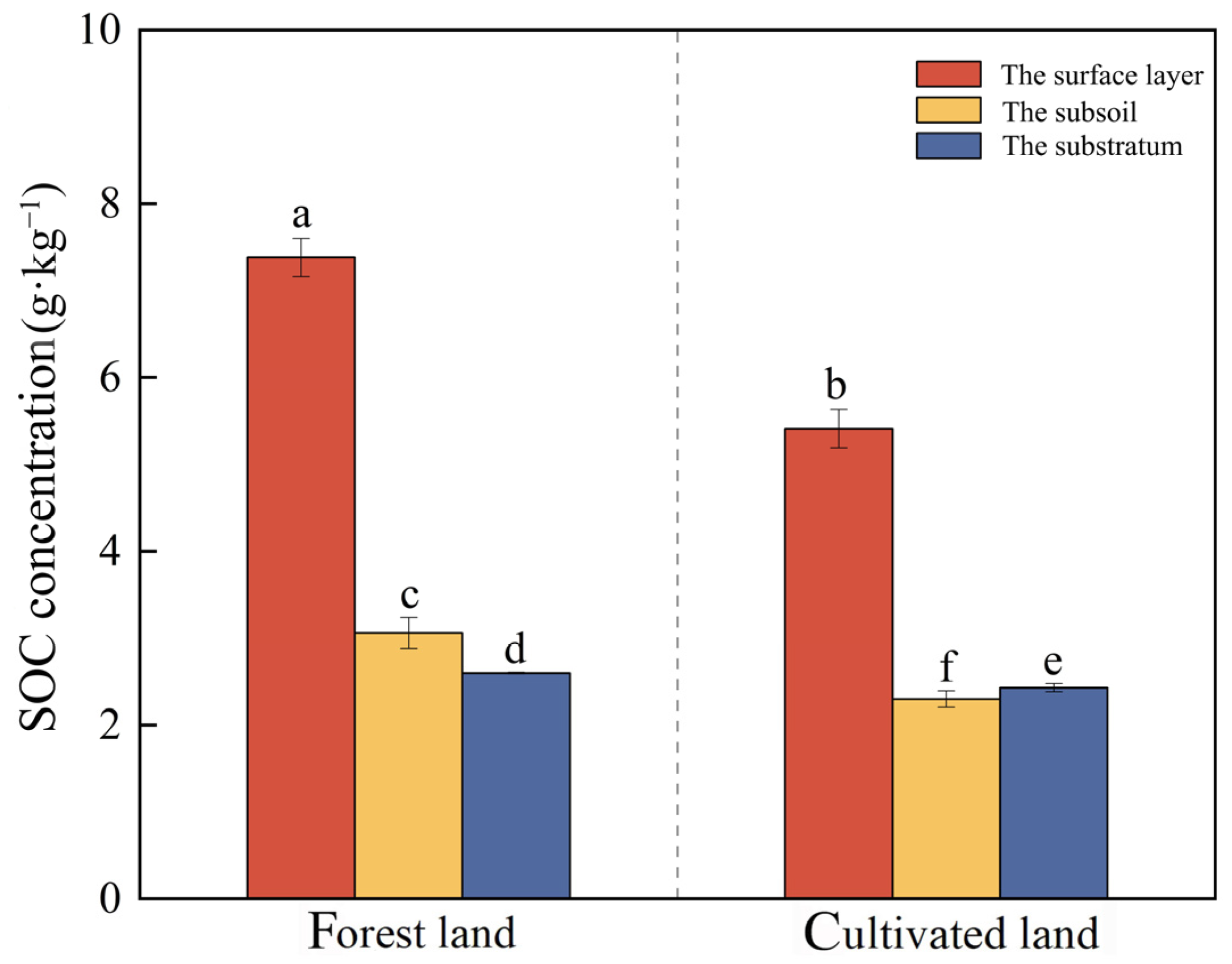

3.1. Distribution of Soil Organic Carbon Content Under Different Land Use Patterns

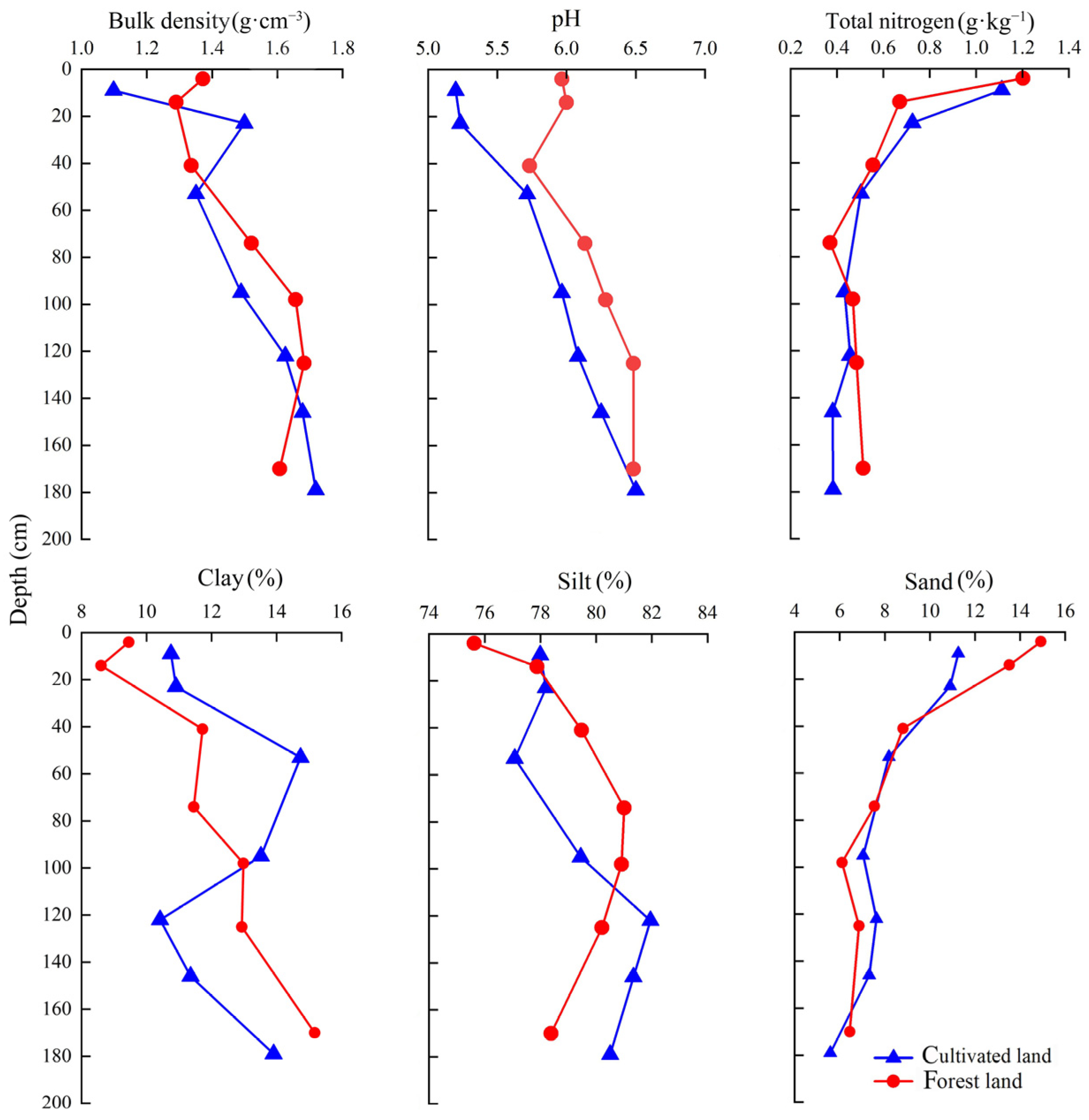

3.2. Relationship Between Soil Organic Carbon Content and Physicochemical Properties

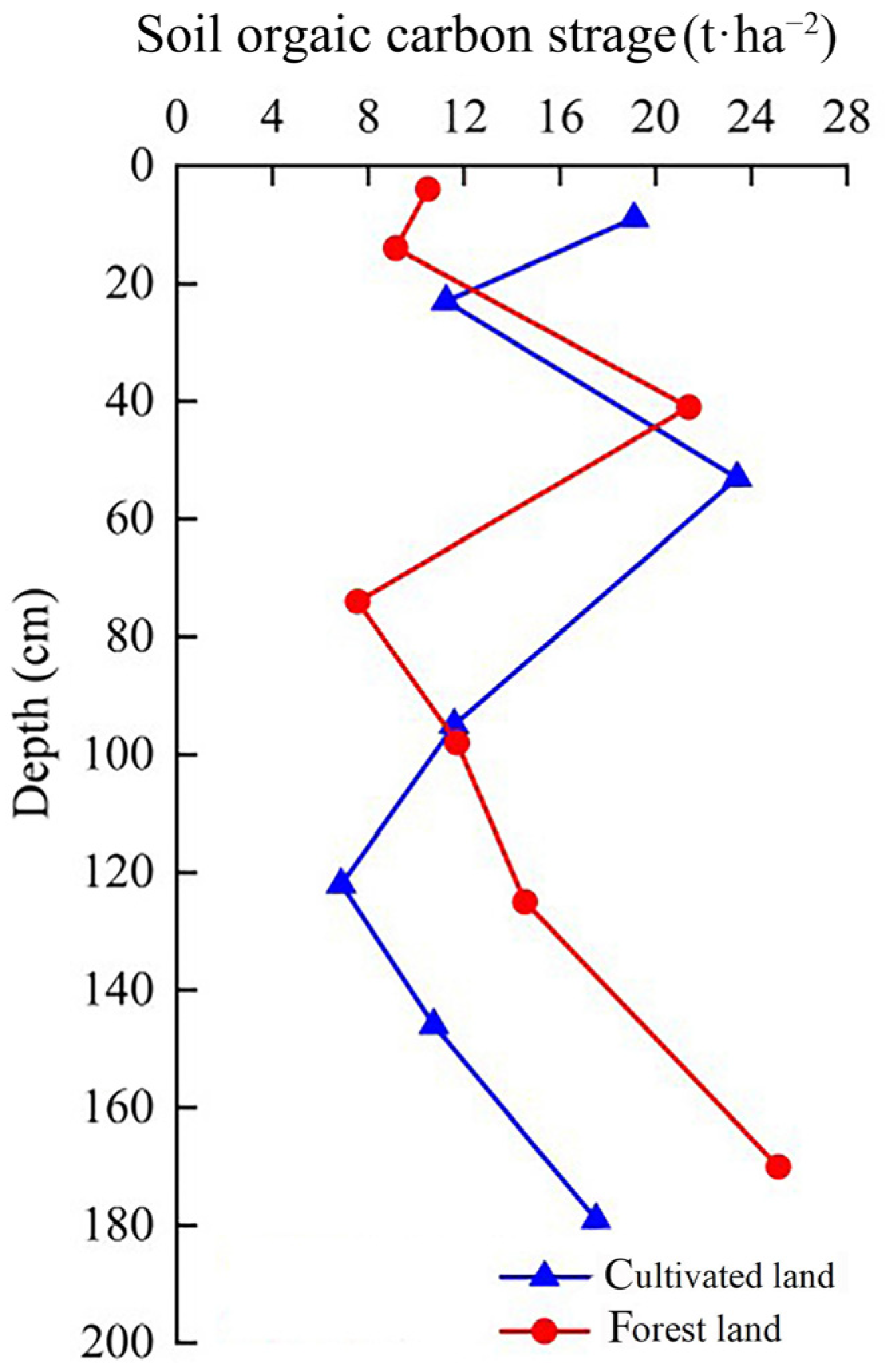

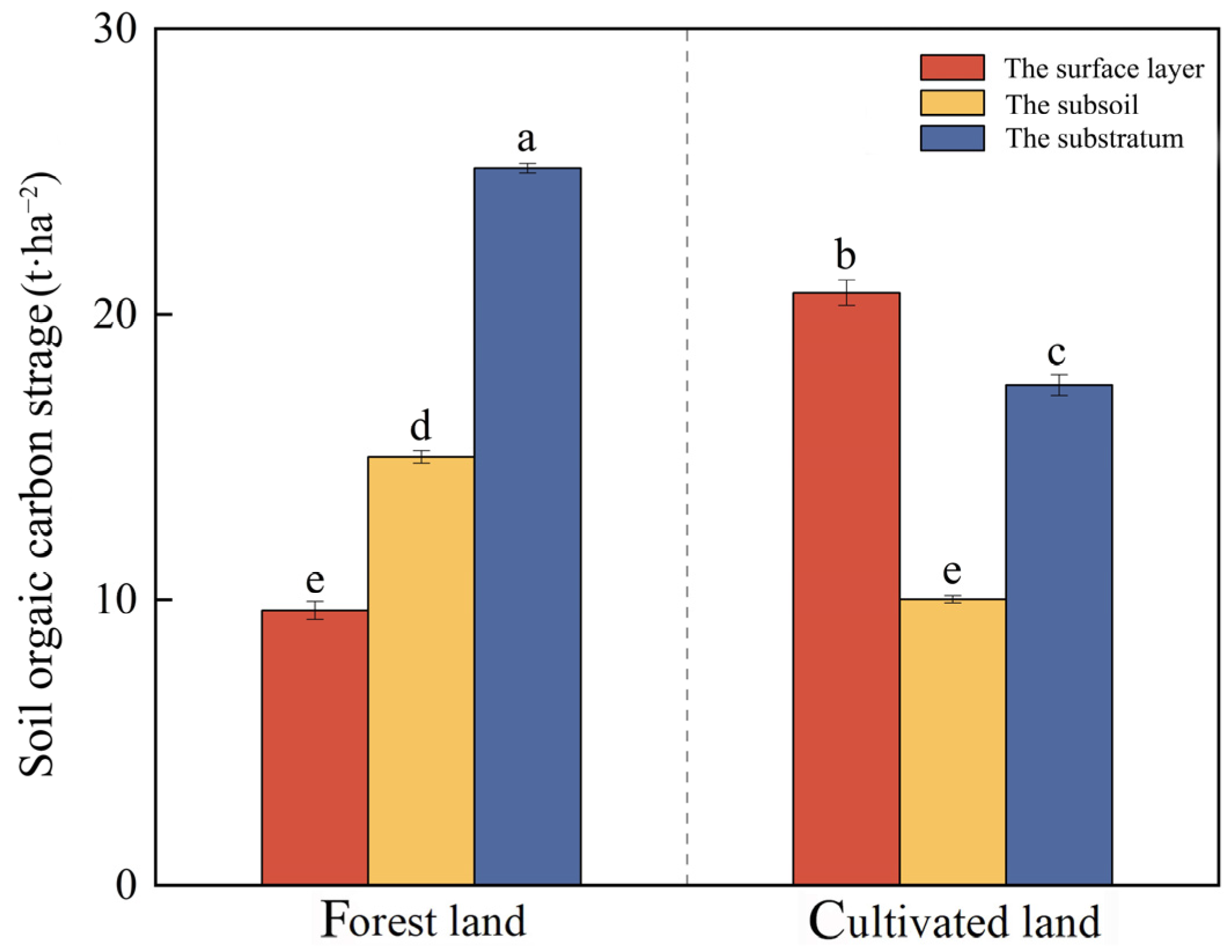

3.3. Distribution of Soil Organic Carbon Storage Under Different Land Use Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Variation in Soil Organic Carbon Content Under Different Land Use Patterns

4.2. Influence of Soil Physical and Chemical Properties on Soil Organic Carbon

4.3. Changes in Soil Organic Carbon Storage Under Different Land Use Patterns

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pan, G. China’s Soil Organic Carbon Pool and Its Evolution and Response to Climate Change. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2008, 4, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.L.; Yan, X.; Wu, X.Z.; Wang, B.; Liu, R.T.; An, H. The influence of desert steppe desertification on soil inorganic carbon and organic carbon. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2019, 33, 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Banger, K.; Toor, G.S.; Biswas, A.; Sidhu, S.S.; Sudhir, K. Soil organic carbon fractions after 16-years of applications of fertilizers and organic manure in a Typic Rhodalfs in semi-arid tropics. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2010, 86, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.X.; Lyu, M.K.; Xie, J.S.; Yang, Z.J.; Jiang, J.; Yang, Y.S. Sources, characteristics and stability of organic carbon in deep soil. J. Subtrop. Resour. Environ. 2013, 8, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, S.L.; Devkota, S.; Rossiter, D.G.; Jetten, V.G. Prediction of soil depth using environmental variables in an anthropogenic landscape, a case study in the Western Ghats of Kerala, India. Catena 2009, 79, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, R.M.; Malepfane, N.M.; van den Dijssel, C.; Arnold, N.; Liu, J.; Müller, K. Comparing deep soil organic carbon stocks under kiwifruit and pasture land uses in New Zealand. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 306, 107190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Liu, C.; Jia, X.; Zhu, J. Changing soil organic carbon with land use and management practices in a thousand-year cultivation region. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 322, 107639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.K.; Wu, M.J. Genetic characteristics and classification of soils developed from parent materials of red bed in the subtropical region: Take Zhejiang Province as an example. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2022, 48, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi, M.; Khormali, F.; Amini, A.; Ayoubi, S. Weathering and soils formation on different parent materials in Golestan Province, Northern Iran. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.L. Accumulation Characteristics and Stabilization Mechanisms of Organic Carbon in Soils Developed from Different Parent Materials in Subtropical Regions; Zhejiang University: Hangzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.H.; Xuan, Q.X.; Wang, L.L.; Yang, D.L.; Zhao, J.N.; Li, G.; Xiu, W.M.; Hong, Y. Study on the Effects of Different Tillage Methods on Soil Organic Carbon Mineralization and Enzyme Activity. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 51, 876–884. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, S.Y.; Sun, Z.X.; Liu, H.B.; Qian, F.K.; Wang, Q.B.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Song, X.D. Human activities drive accelerated soil aggregation in Quaternary red soil. Catena 2025, 258, 109232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.L.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.L.; Chen, F. The impact of conservation tillage on net carbon release from farmland ecosystems. Chin. J. Ecol. 2007, 12, 2035–2039. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M.W.I.; Torn, M.S.; Abiven, S.; Dittmar, T.; Guggenberger, G.; Janssens, I.A.; Kleber, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Lehmann, J.; Manning, D.A.C.; et al. Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature 2011, 478, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, S.; Barot, S.; Barré, P.; Bdioui, N.; Mary, B.; Rumpel, C. Stability of organic carbon in deep soil layers controlled by fresh carbon supply. Nature 2007, 450, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunlanit, B.; Butnan, S.; Vityakon, P. Land–use changes influencing C sequestration and quality in topsoil and subsoil. Agronomy 2019, 9, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Xin, Z.B. Effects of different ecological restoration patterns on soil organic carbon in gullies of Loess Plateau. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Du, J.; Sun, J.H.; Wu, H.Y.; Sun, N.K.; Suo, D.R.; Zhao, X.N.; Xu, Y.; Xia, L.L.; Ma, Y.Q.; et al. Long-term fertilization effects on organic carbon content and carbon storage in irrigated desert soil. Soils 2025, 57, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.L.; Li, D.C. Field Soil Description and Sampling Manual; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, R.B.; Reinsch, T.G. Bulk density and linear extensibility. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 4 Physical Methods; SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 2002; pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.Y.; Sun, Z.X.; Wang, Q.B.; Sun, Z.G.; Jiang, Z.D.; Gu, H.Y.; Libohova, Z.; Owens, P.R. Characteristics of the typical loess profile with a macroscopic tephra layer in the northeast China and the paleoclimatic significance. Catena 2021, 198, 105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.W. Soil pH and soil acidity. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods; SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 475–490. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.R.; Wang, Z.Q. Soil Analytical Chemistry; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1985; pp. 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Soil Physical and Chemical Analysis; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 1978; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.X.; Zhang, N.W.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.B.; Zhang, G.L. The Long-Term Deep Loessal Sediments of Northeast China: Loess or Loessal Paleosols? Quaternary 2023, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.X.; Han, X.Z.; Li, L.J.; Zou, W.X.; Lu, X.C.; Qiao, Y.F. The influence of land use patterns on the distribution and carbon storage of organic matter in the black soil profile. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 26, 965. [Google Scholar]

- Stolt, M.H.; Baker, J.C. Quantitative comparison of soil and saprolite genesis: Examples from the Virginia Blue Ridge and Piedmont. Southeast. Geol. 2000, 39, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zhou, W.J.; Cheng, P. Soil organic carbon fractions and 14C ages through 70 years of cropland cultivation. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 195, 104415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; Sun, Y.; Gao, L.; Cui, X.Y. Research Progress on Influencing Factors of Soil Organic Carbon Stability. Chin. J. Ecol. Cloth. Ind. 2018, 26, 222–230. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.Y.; Sun, Z.X.; Zheng, Y.B.; Wang, H.L.; Wang, J.Q. Establishing a soil health assessment system for quaternary red soils (Luvisols) under different land use patterns. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wang, Q.Q.; Li, D.Q.; Xiao, H.B.; Nie, X.D.; Yuan, Z.J.; Zheng, M.G.; Liao, Y.S.; Liang, C. Characteristics of altitude gradient changes of soil organic carbon and components in the Nanling Mountains. Chin. Soil Sci. Bull. 2022, 53, 374–383. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, P.X. The Influence of Land Use Types in North China on Soil Respiration, Organic Carbon components and water-stable aggregates. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 27, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesmeier, M.; Hübner, R.; Barthold, F.; Spörlein, P.; Geuß, U.; Hangen, E.; Reischl, A.; Schilling, B.; Lützow, M.V.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Amount, distribution and driving factors of soil organic carbon and nitrogen in cropland and grassland soils of southeast Germany (Bavaria). Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 176, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Duan, L.X.; Huang, Y.X.; Wang, H. Characteristics of organic carbon and its components in major agricultural soils in the mid-subtropical region. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 11, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, R.Y.; Fu, B.J.; Liu, G.H.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.L. The effects of afforestation on soil organic and inorganic carbon: A case study of the Loess Plateau of China. Catena 2012, 95, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.G.; Guo, J.P.; Yang, X.Y.; Tian, X.P. Distribution characteristics and carbon storage of soil organic carbon profile in typical vegetation of Luya Mountain. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2011, 31, 3009–3019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, T.; Chen, N.L. Distribution characteristics and influencing factors of soil carbon and nitrogen in the vertical zone of the northern foot of the Qilian Mountains. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 20, 518–524. [Google Scholar]

- Priess, J.A.; Koning, G.H.J.; Veldkamp, A. Assessment of interactions between land use change and carbon and nutrient fluxes in Ecuador. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2001, 85, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollins, P.; Swanston, C.; Kramer, M. Stabilization and destabilization of soil organic matter—A new focus. Biogeochemistry 2007, 85, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Sun, Z.X. Estimation of cation exchange capacity for low-activity clay soil fractions using experimental data from south China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.X.; Li, X.S.; Li, D.C.; Han, Z.Y.; Zhang, G.L.; Li, X.S.; Yang, P.; He, X.W.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Li, R.Q.; et al. Spatial Variation of Surface Soil Organic Carbon in Farmland in the Mountainous Area of Southern Anhui Province and Its Influencing Factors: A Case Study of Xuancheng District. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2014, 45, 1424–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Konen, M.E.; Burras, C.L.; Sandor, J.A. Organic carbon, texture, and quantitative color measurement relationships for cultivated soils in north central Iowa. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2003, 67, 1823–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottingham, A.T.; Meir, P.; Velasquez, E.; Turner, B.L. Soil carbon loss by experimental warming in a tropical forest. Nature 2020, 584, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.Y.; Sun, Z.X.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.Q. Construction and application of the Phaeozem health evaluation system in Liaoning Province, China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, B.R.; Dou, Y.X.; Xue, Z.J.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.Q.; Liang, C.; An, S.S. Research progress on the transformation and stability of Soil Organic Carbon from Plant and Microbial sources. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 35, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, L.C.; Meir, P.; Nottingham, A.T.; Reay, D.S.; Stott, A.W.; Salinas, N.; Whitaker, J. Carbon and nitrogen inputs differentially affect priming of soil organic matter in tropical lowland and montane soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 129, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.X.; Wang, S.N.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.B.; Zhang, G.L. Iron pools of the typical loess--paleosol sequence and their environmental significance in northeastern China. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotching, W.E. Carbon stocks in Tasmanian soils. Soil Res. 2012, 50, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile | Occurrence Layer | Depth (cm) | Color (Dry State) | Structure and Its Degree of Development | Soil Texture | Fixation (Dry) | Other Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated land 21-N001 | Ap1 | 0–17 | 10YR 4/3 | Moderately developed mesenchymal | Silty loam | Soft | A very small amount of iron-manganese nodules |

| Ap2 | 17–28 | 10YR 4/4 | Moderately developed thin sheet | Silty loam | Slightly hard | A very small amount of iron-manganese nodules | |

| ABr | 28–78 | 10YR 5/4 | Moderately developing mass | Silty loam | Slightly hard | A small amount of iron-manganese nodules | |

| Btrq1 | 78–111 | 10YR 5/4 | Moderately developed middle ridge block | Silty loam | Hard | A small amount of clay film, iron-manganese nodules and silica neoformation powder | |

| Btrq2 | 111–133 | 10YR 4/4 | Moderately developed middle ridge block | Silty loam | Hard | A moderate amount of clay film, a small amount of iron and manganese nodules and a large amount of silica neoformation powder | |

| Btrq3 | 133–158 | 10YR 4/3 | Moderately developed middle ridge block | Silty loam | Very hard | A moderate amount of clay film, a small amount of iron and manganese nodules and a large amount of silica neoformation powder | |

| Cr | 158–200 | 10YR 5/4 | Moderately developed middle ridge block | Silty loam | Very hard | A small amount of iron-manganese nodules | |

| Forest land 21-N006 | Ahr | 0–7 | 7.5YR 6/4 | Moderately developing mass | Silty loam | soft | A small amount of iron-manganese nodules |

| ABr | 7–20 | 7.5YR 4/4 | Moderately developing mass | Silty loam | soft | A small amount of iron-manganese nodules | |

| Br | 20–62 | 10YR 4/3 | Moderately developing mass | Silty loam | Slightly hard | A small amount of iron-manganese nodules | |

| Btrq1 | 62–85 | 10YR 5/4 | Moderately developed small ridges | Silty loam | Hard | A small amount of iron-manganese nodules and a moderate amount of silica neoformation powder | |

| Btrq2 | 85–110 | 10YR 4/3 | Moderately developed small masses | Silty loam | Hard | A small amount of iron and manganese nodules and a large amount of silica neoformation powder | |

| Btrq3 | 110–140 | 10YR 5/3 | Moderately developed middle ridge block | Silty loam | Very hard | A small amount of iron and manganese nodules and a large amount of silica neoformation powder | |

| Cr | 140–200 | 10YR 5/6 | Moderately developed middle ridge block | Silty loam | Very hard | Moderate iron-manganese nodules |

| Land Utilization Type | Bulk Density | pH | Total Nitrogen | Clay | Silt | Sand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest land | −0.55 ** | −0.45 * | 0.94 ** | 0.63 ** | −0.75 ** | 0.60 ** |

| Cultivated land | −0.78 ** | −0.86 ** | 0.96 ** | −0.42 | −0.62 ** | 0.81 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cui, S.-Y.; Sun, Z.-X.; Duan, S.-Y.; Qiu, W.-W.; Jiang, Y.-Y. Cultivation Management Reshapes Soil Profile Configuration and Organic Carbon Sequestration: Evidence from a 45-Year Field Study. Agronomy 2026, 16, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010110

Cui S-Y, Sun Z-X, Duan S-Y, Qiu W-W, Jiang Y-Y. Cultivation Management Reshapes Soil Profile Configuration and Organic Carbon Sequestration: Evidence from a 45-Year Field Study. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010110

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Si-Yu, Zhong-Xiu Sun, Si-Yi Duan, Wei-Wen Qiu, and Ying-Ying Jiang. 2026. "Cultivation Management Reshapes Soil Profile Configuration and Organic Carbon Sequestration: Evidence from a 45-Year Field Study" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010110

APA StyleCui, S.-Y., Sun, Z.-X., Duan, S.-Y., Qiu, W.-W., & Jiang, Y.-Y. (2026). Cultivation Management Reshapes Soil Profile Configuration and Organic Carbon Sequestration: Evidence from a 45-Year Field Study. Agronomy, 16(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010110