Enhanced Salt Stress Tolerance in Maize Using Biostimulant and Biosurfactant Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

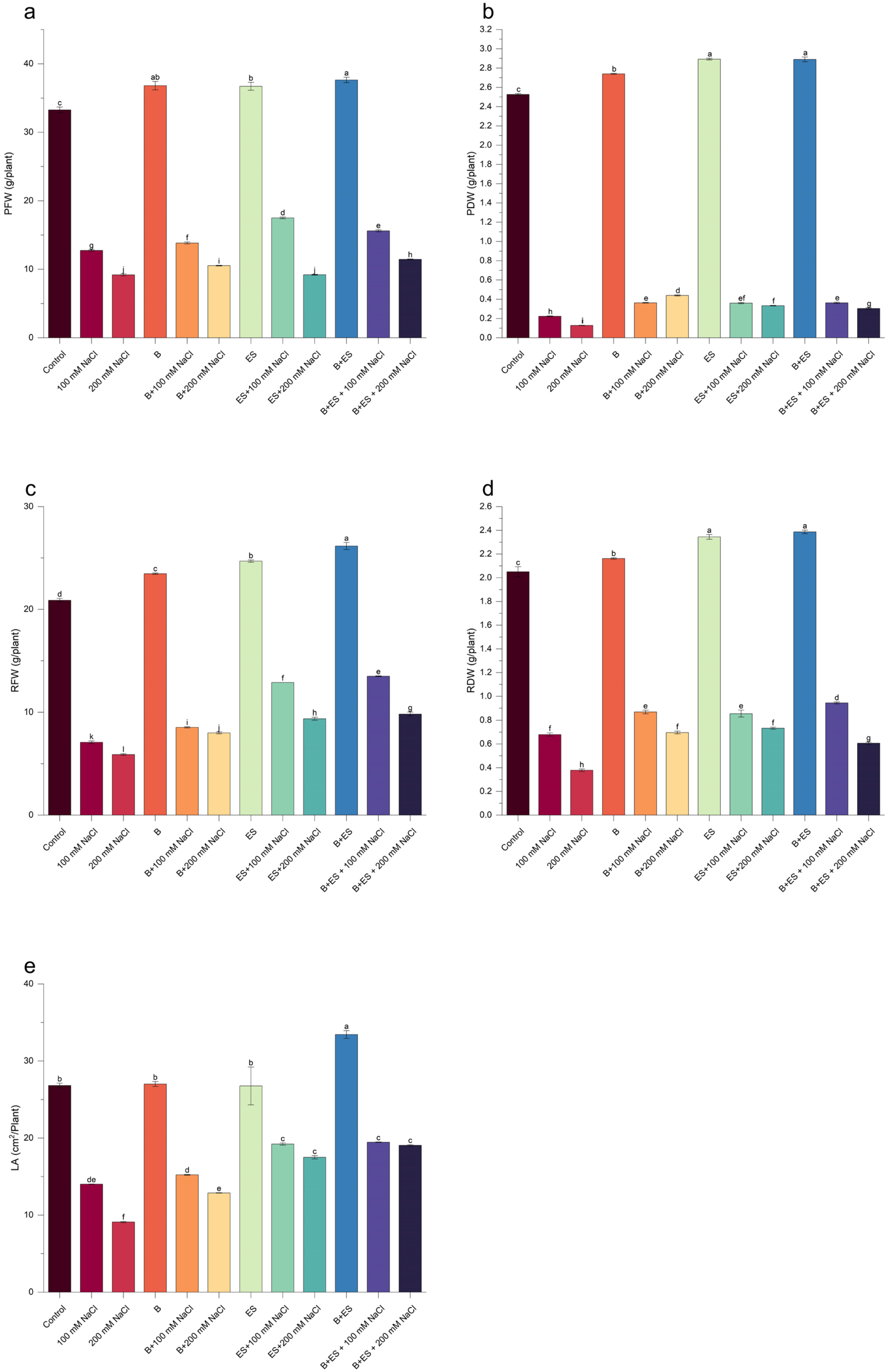

2.1. Plant Height, Fresh Weight, and Dry Weight Measurements

2.2. Leaf Area

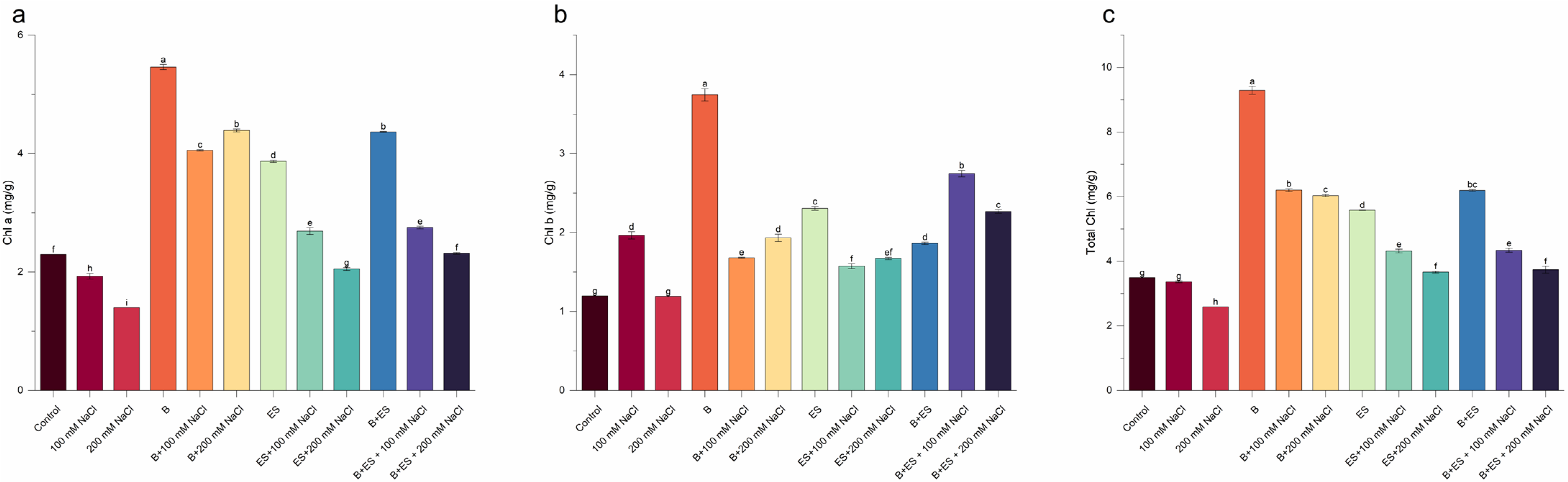

2.3. Chlorophyll Content

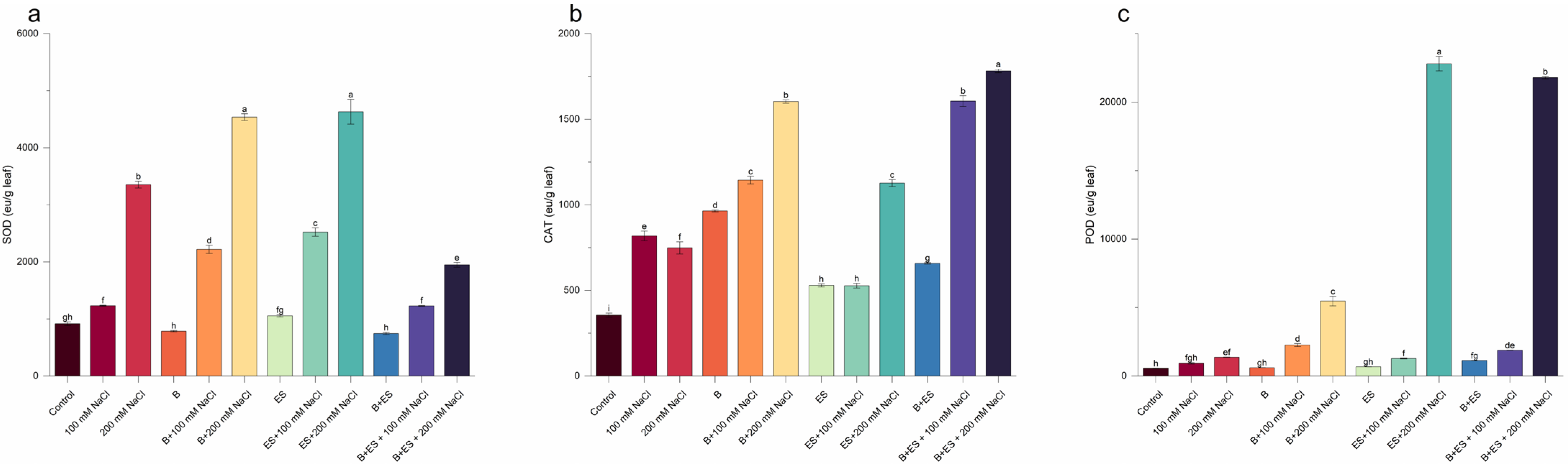

2.4. Antioxidant Enzymes

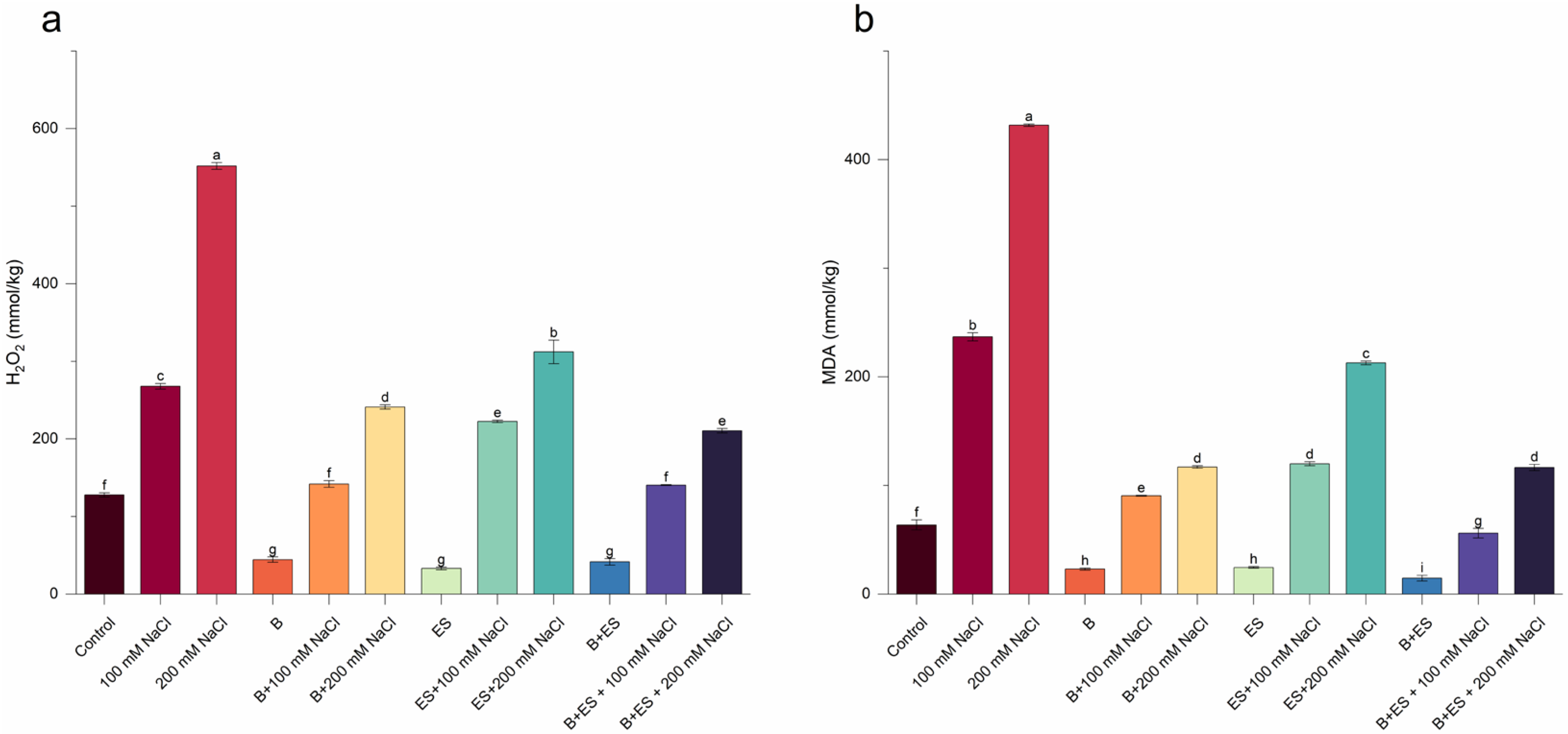

2.5. Hydrogen Peroxide

2.6. Malondialdehyde

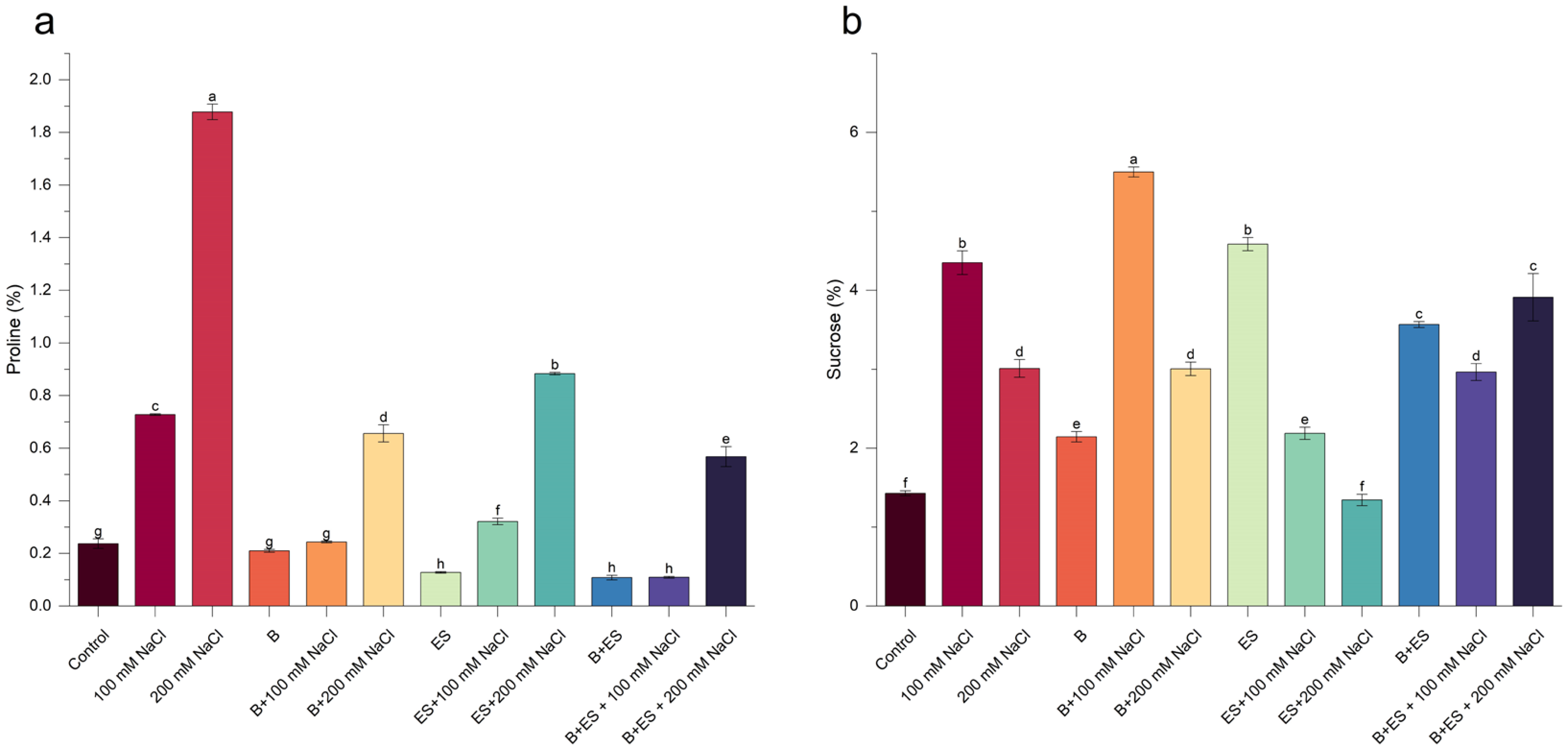

2.7. Proline

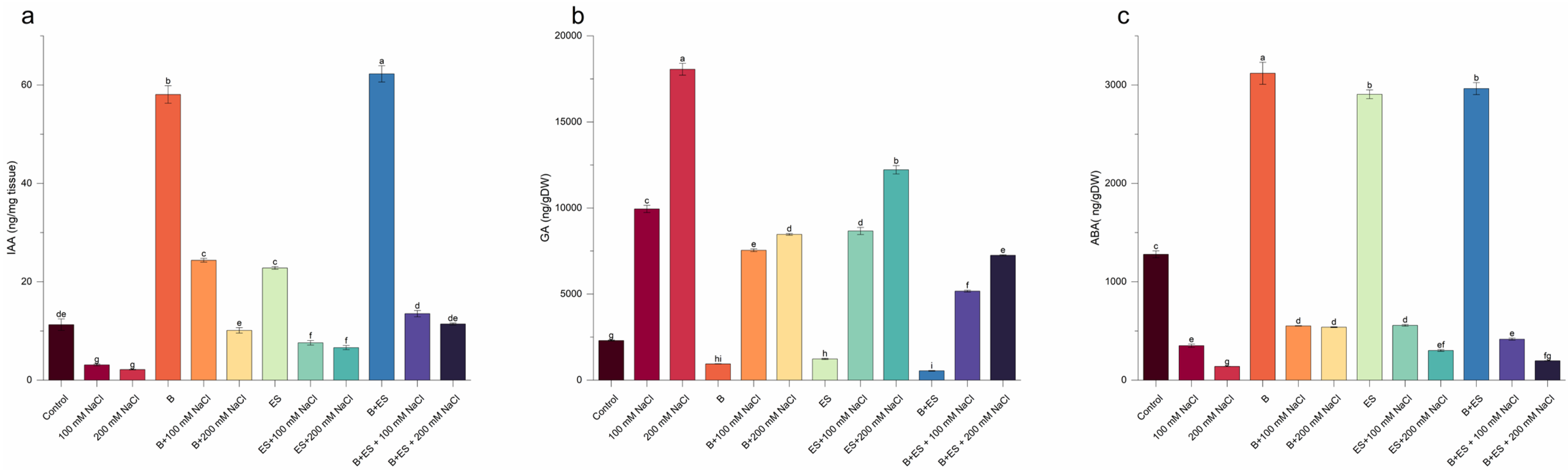

2.8. Hormones

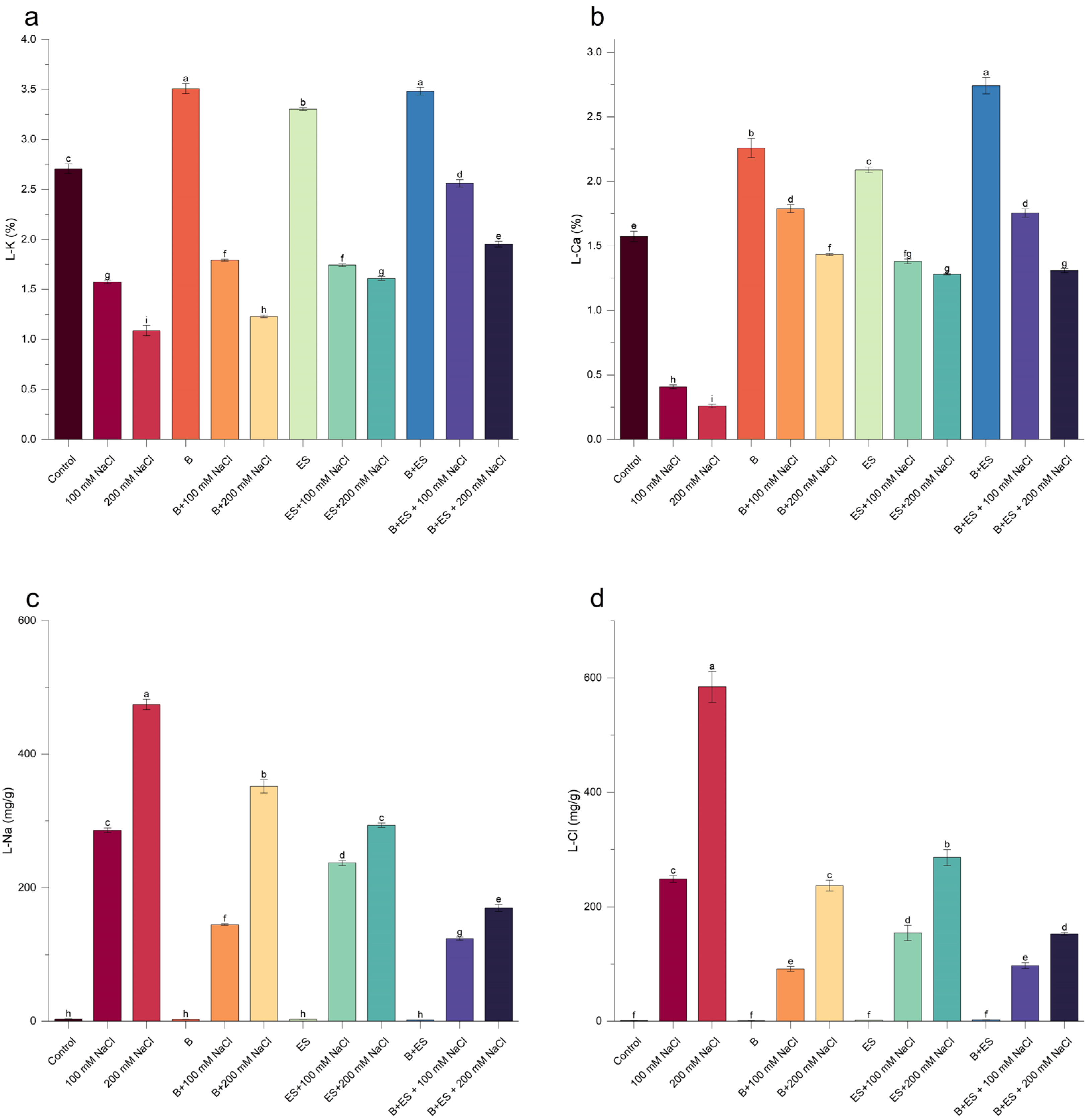

2.9. Plant Nutrient Elements

2.10. Statistical Analysis

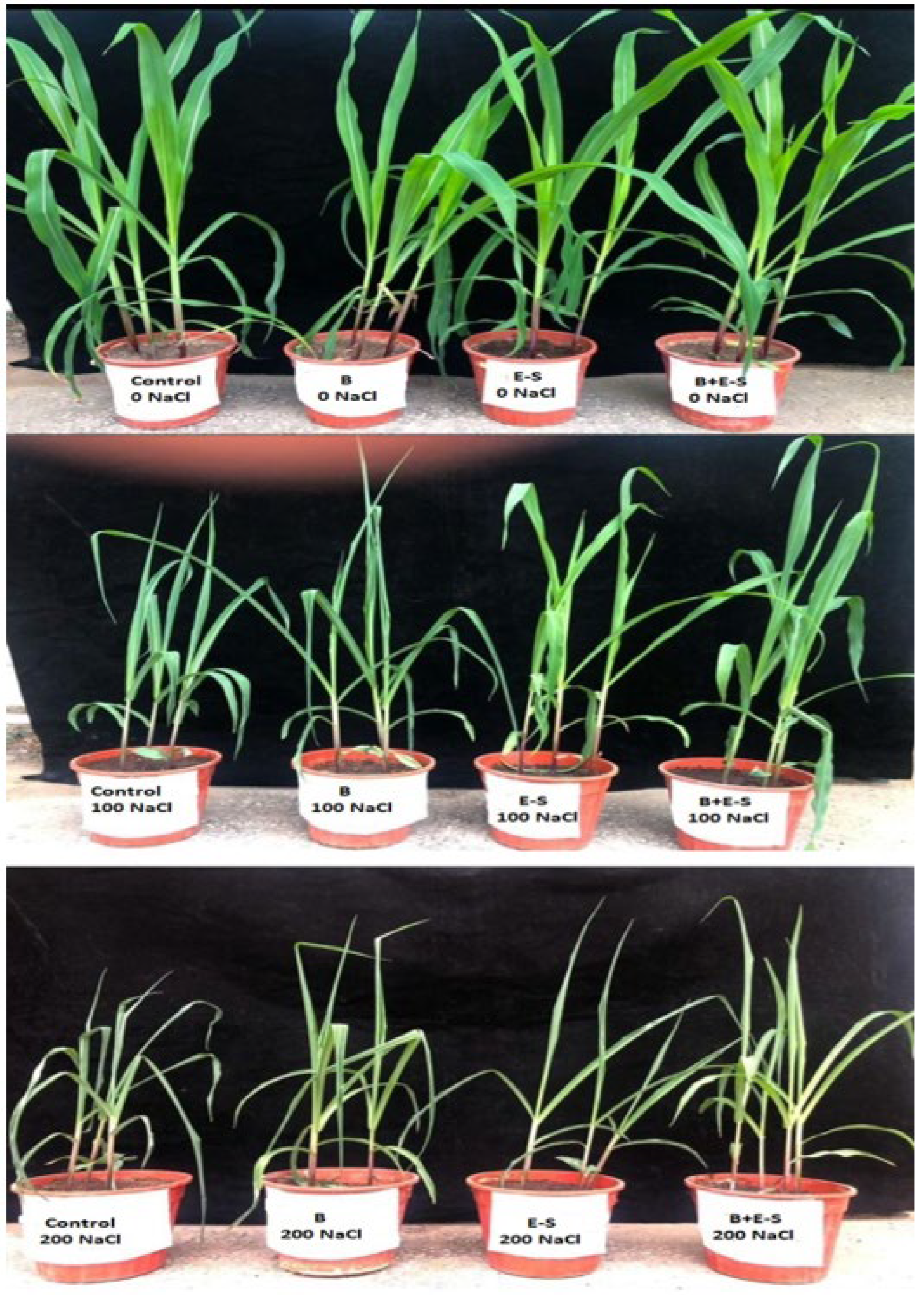

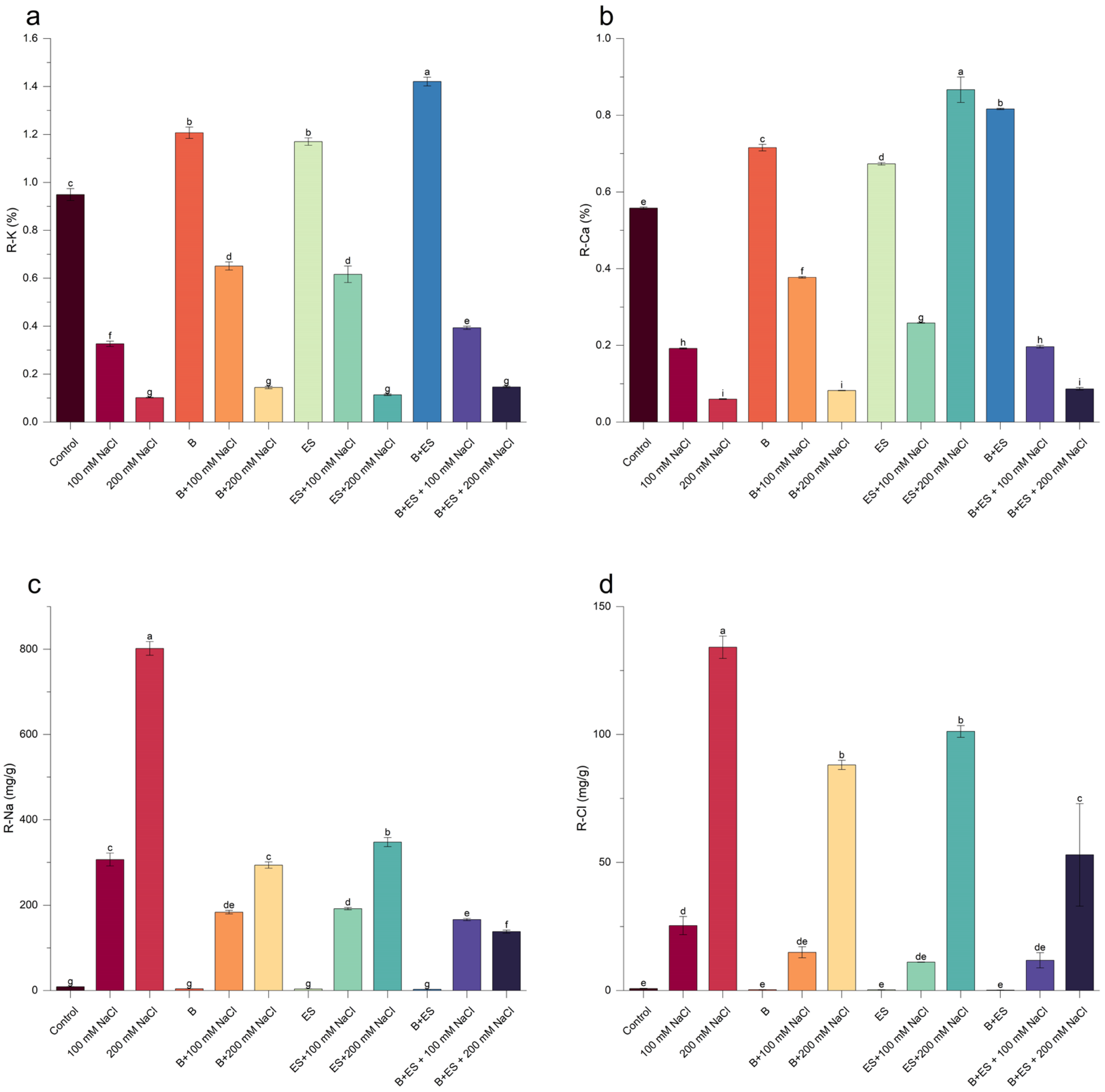

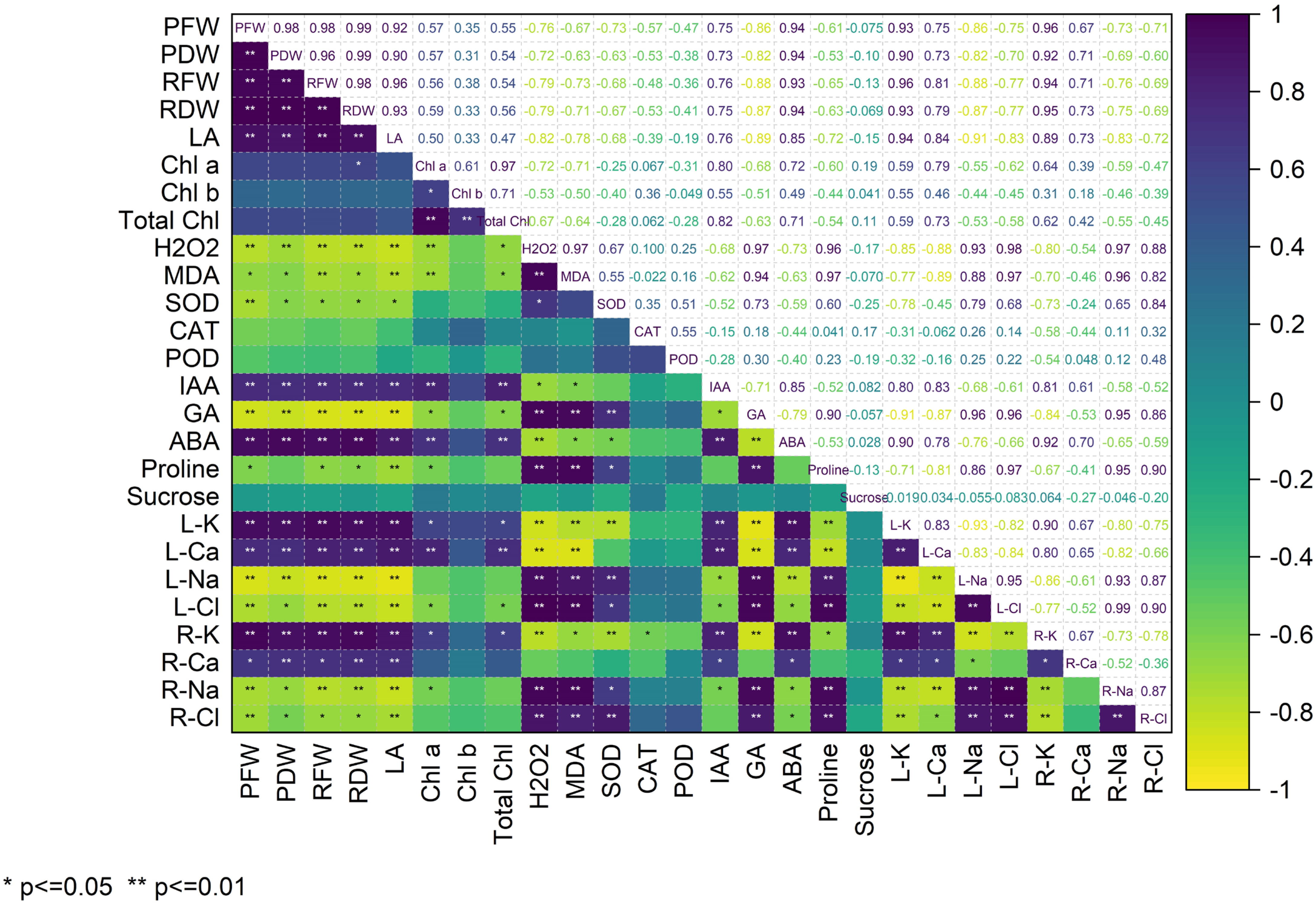

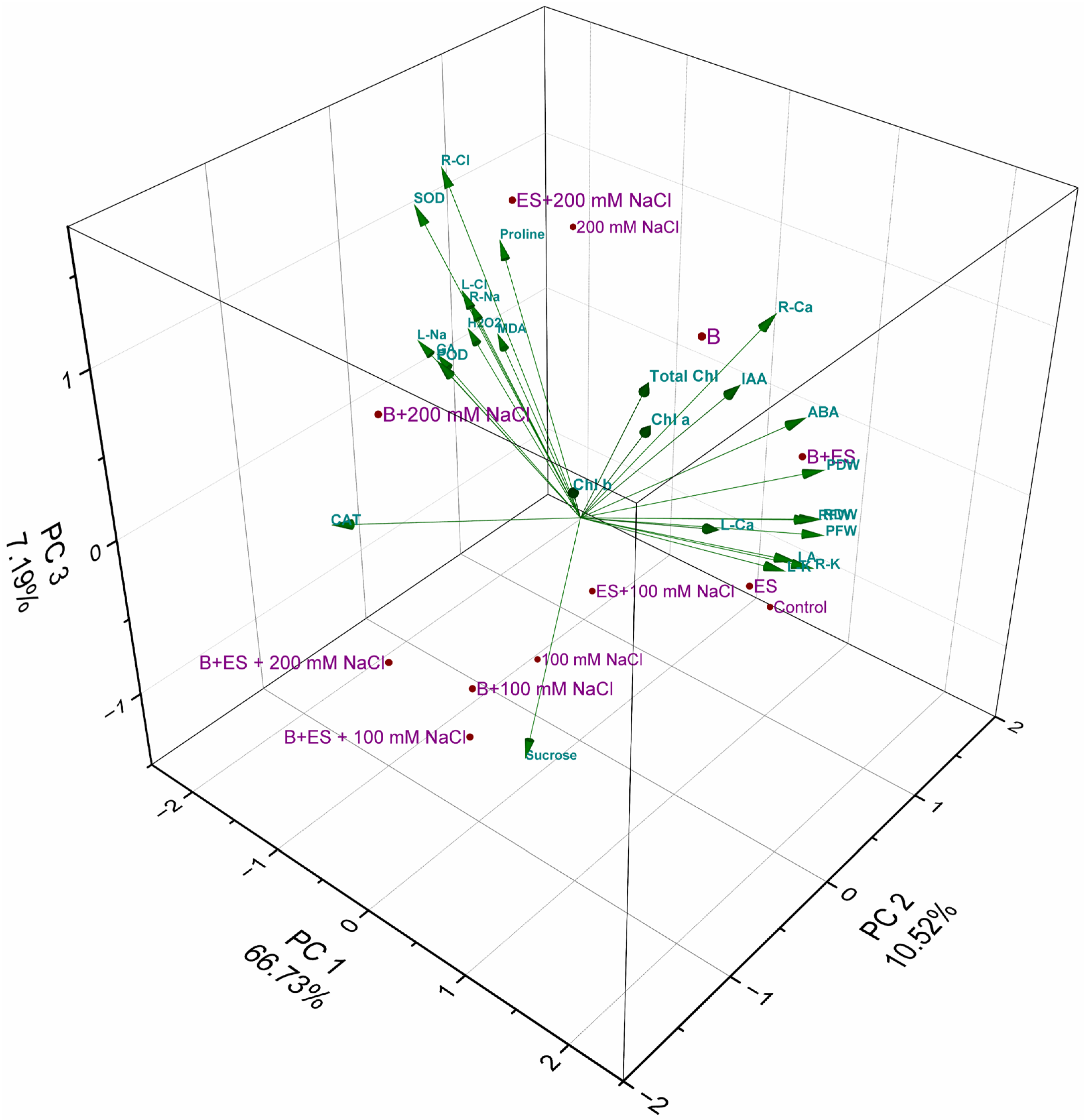

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Amato, R.; Del Buono, D. Use of a biostimulant to mitigate salt stress in maize plants. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Najafi Alamdarlo, H.; Mosavi, S.H. The Effects of Climate Change and Groundwater Salinity on Farmers’ Income Risk. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 110, 105893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Sarkar, B.; Jat, H.S.; Sharma, P.C.; Bolan, N.S. Soil salinity under climate change: Challenges for sustainable agriculture and food security. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Global Soil Partnership 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/global-soil-partnership/resources/highlights/detail/en/c/1412475/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Hussain, S.; Shaukat, M.; Ashraf, M.; Zhu, C.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, J. Salinity Stress in Arid and Semi-arid Climates. In Effects and Management in Field Crops 2019. Climate Change and Agriculture; Hussain, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Amoanimaa-Dede, H.; Zeng, F.; Deng, F.; Xu, S.; Chen, Z.H. Stomatal regulation and adaptation to salinity in glycophytes and halophytes. In Advances in Botanical Research; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 103, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil Salinity: A Serious Environmental Issue and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria as One of the Tools for Its Alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M.; Waheed, A.; Wahab, A.; Majeed, M.; Nazim, M.; Liu, Y.H.; Li, L.; Li, W. Soil salinity and drought tole-rance: An evaluation of plant growth, productivity, microbial diversity, and amelioration strategies. Plant Stress 2023, 11, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Agricultural Drainage Water Management in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas; FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 61; Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, E.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Yuce, M.; Ors, S.; Araz, O.; Torun, U.; Argin, S. Exogenous dopamine mitigates the effects of salinity stress in tomato seedlings by alleviating the oxidative stress and regulating phytohormones. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2024, 46, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Aydin, M.; Yuce, M.; Agar, G.; Ors, S.; İlhan, E.; Ciltas, A.; Ercıslı, S.; Yildirim, E. Chrysin alleviates salt stress in tomato by physiological, biochemical, and genetic mechanisms. Rhizosphere 2024, 32, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, D.A.; El-Ghamry, A.M.; El-Sherpiny, M.A.; Soliman, M.A.E.; Nemeata Alla, A.A.; Helmy, A.A. Titanium: An Element of Non-Biological Atmospheric Nitrogen Fixation and A Regulator of Sugar Beet Plant Tolerance to Salinity. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 62, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Luo, J.; Hao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, B.; Guo, W. Bio-organic fertilizer promoted phytoremedia-tion using native plant leymus chinensis in heavy Metal(loid)s contaminated saline soil. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 327, 121599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, T.; Lu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, P.; Jia, B.; Hao, B.; Wang, Y.; Guo, W. Bioorganic fertilizers improve the adaptability and remediation efficiency of Puccinellia distans in multiple heavy metals-contaminated saline soil by regulating the soil microbial community. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elzaher, M.A.; El-Desoky, M.A.; Khalil, F.A.; Eissa, M.A.; Amin, A.E.-E.A. Interactive Effects of K-Humate, Proline and Si and Zn Nanoparticles in Improving Salt Tolerance of Wheat in Arid Degraded Soils. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 62, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Zhou, X.; Fu, Y.; Song, B.; Yan, H.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Q.; Ye, H.; Qin, L.; Lai, C. Biochar-compost as a new option for soil improvement: Application in various problem soils. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 870, 162024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, E.A.; Mohamed, I.R.; Abd El-Hameed, A.M.; Zaghloul, E.A.M. The Co-Addition of Soil Organic Amendments and Natural BioStimulants Improves the Production and Defenses of the Wheat Plant Grown under the Dual Stress of Salinity and Alkalinity. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 62, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, H.M.; Zaghloul, R.A.; Hassan, E.A.; El-Zehery, H.R.A.; Salem, A.A. New strains of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in combinations with humic acid to enhance squash growth under saline stress. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 61, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Amjad, S.F.; Saleem, M.H.; Yasmin, H.; Imran, M.; Riaz, M.; Ali, Q.; Joyia, F.A.; Mobeen; Ahmed, S.; et al. Fo-liar application of ascorbic acid enhances salinity stress tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) through modulation of morphophysio- biochemical attributes, ions uptake, osmo-protectants and stress response genes expression. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 4276–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, M.; Ekinci, M.; Argin, S.; Brinza, M.; Yildirim, E. Drought stress amelioration in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) seedlings by biostimulant as regenerative agent. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1211210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuce, M.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Agar, G.; Aydin, M.; Ilhan, E.; Yildirim, E. Chrysin mitigates copper stress by regu-lating antioxidant enzymes activity, plant nutrient and phytohormones content in pepper. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 328, 112887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Khan, A.; Asif, M.; Khan, F.; Ansari, T.; Shariq, M.; Siddiqui, M.A. Biological control: A sustainable and practical approach for plant disease management. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2020, 70, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, S.; Manoli, A.; Quaggiotti, S. A Novel Biostimulant, Belonging to Protein Hydrolysates, Mitigates Abiotic Stress Effects on Maize Seedlings Grown in Hydroponics. Agronomy 2019, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuce, M.; Yildirim, E.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Ilhan, E.; Aydin, M.; Agar, G.; Ucar, S. N-acetyl-cysteine mitigates arsenic stress in lettuce: Molecular, biochemical, and physiological perspective. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 207, 108390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lorente, S.E.; Martí-Guillén, J.M.; Pedreño, M.Á.; Almagro, L.; Sabater-Jara, A.B. Higher plant-derived bios-timulants: Mechanisms of action and their role in mitigating plant abiotic stress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, S.; Hajfarajollah, H.; Mokhtarani, B.; Noghabi, K.A. Physiochemical and thermodynamic characterization of lipopeptide biosurfactant secreted by Bacillus tequilensis HK01. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 91836–91845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajfarajollah, H.; Mehvari, S.; Habibian, M.; Mokhtarani, B.; Noghabi, K.A. Rhamnolipid biosurfactant adsorption on a plasma-treated polypropylene surface to induce antimicrobial and antiadhesive properties. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 33089–33097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofi, N.; Ivshina, I.B. Microbial surfactants and their use in field studies of soil remediation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 93, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajfarajollah, H.; Eslami, P.; Mokhtarani, B.; Akbari Noghabi, K. Biosurfactants from probiotic bacteria: A review. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2018, 65, 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Afzal, S.; Parveen, A.; Kamran, M.; Javed, M.R.; Abbasi, G.H.; Ali, S. Silicon mediated improvement in the growth and ion homeostasis by decreasing Na+ uptake in maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars exposed to salinity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 158, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Crop Statistics. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/ (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Ray, D.K.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.C.; Foley, J.A.; Hart, J.P. Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66428. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.R.; Wang, S.; Li, M.; Lv, H.Y.; Wang, D.W.; Ge, Y.Q.; Wei, X.; Yang, W.C. Current status and perspective of maize breeding. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2018, 19, 435–446. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.X.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhang, M.; Cao, Y.B.; Jiang, C.F. Recent advancement of molecular understanding of salt tolerance in maize. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2021, 23, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Song, H.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, C. Advances in deciphering salt tolerance mechanism in maize. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liang, X.; Yin, P.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, C. A domestication-associated reduction in K+-preferring HKT transporter activity underlies maize shoot K+ accumulation and salt tolerance. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpici, E.B.; Çelik, B.; Bayram, N.G. Effects of salt stress on germination of some maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 4918–4922. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, X.; Yue, L.; Wang, C.; Tao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xing, B. Foli-ar-applied cerium oxide nanomaterials improve maize yield under salinity stress: Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and rhizobacteria regulation. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 299, 118900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, N.; Raza, Z.A.; Mahmood, S. Effect of salinity stress on various growth and physiological attributes of two contrasting maize genotypes. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2020, 63, e20200072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Ding, R.; Du, T.; Kang, S.; Tong, L.; Gu, S.; Gao, S.; Gao, J. Stomatal conductance modulates maize yield through water use and yield components under sa-linity stress. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 294, 108717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Hasan, M.; Hafeez, A.S.M.G.; Chowdhury, M.; Pramanik, M.; Konuşkan, Ö.; Dubey, A.; Kumar, A.; El Sabagh, A.; et al. Salinity stress in maize: Consequences, tolerance mechanisms, and management strategies. OBM Genet. 2024, 8, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadresan, M.; Luthe, D.S.; Reddivari, L.; Chaichi, M.R.; Yazdani, D. Effect of salinity stress and surfactant treatment on physiological traits and nutrient absorption of fenugreek plant. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2015, 46, 2807–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichi, M.R.; Keshavarz-Afshar, R.; Saberi, M.; Rostamza, M.; Falahtabar, N. Alleviation of salinity and drought stress in corn production using a non-ionic surfactant. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2016, 26, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, B.; Wang, X.; Saleem, M.H.; Sumaira, H.A.; Afridi, M.S.; Khan, S.; Zaib-Un-Nisa, U.I.; Amaral Júnior, A.T.D.; Alatawi, A.; Ali, S. PGPR-Mediated Salt Tolerance in Maize by Modulating Plant Physiology, Antioxidant Defense, Compatible Solutes Accumulation and Bio-Surfactant Producing Genes. Plants 2022, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnon, D.I. The water culture method for growing plants without soil. Calif. Agric. Expt. Stn. Circ. 1950, 347, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, R.; Ramanarao, M.V.; Lee, S.; Kato, N.; Baisakh, N. Ectopic expression of ADP ribosylation factor 1 (SaARF1) from smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora Loisel) confers drought and salt tolerance in transgenic rice and Arabidop-sis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2014, 117, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Angelini, R.; Federico, R. Histochemical evidence of polyamine oxidation and generation of hydrogen- peroxide in the cell wall. J. Plant Physiol. 1989, 135, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, R.; Manes, F.; Federico, R. Spatial and functional correlation between diamine-oxidase and peroxidase ac-tivities and their dependence upon deetiolation and wounding in chick-pea stems. Planta 1990, 182, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yordanova, R.Y.; Christov, K.N.; Popova, L.P. Antioxidative enzymes in barley plants subjected to soil flooding. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004, 51, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozden, M.; Demirel, U.; Kahraman, A. Effects of proline on antioxidant system in leaves of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) exposed to oxidative stress by H2O2. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 119, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Ors, S.; Dursun, A.; Yildirim, E. Improving salt tolerance of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) with hydrogen sulfide. Photosynthetica 2023, 61, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuraishi, S.; Tasaki, K.; Sakurai, N.; Sadatoku, K. Changes in levels of cytokinins in etiolated squash seedlings after il-lumination. Plant Cell Physiol. 1991, 32, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Yildirim, E.; Güneş, A.; Kotan, R.; Dursun, A. Effect of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on growth, nutrient, organic acid, amino acid and hormone content of cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L. var. botrytis) transplants. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2014, 13, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, J.; Luyssaert, S.; Verheyen, K. Use and abuse of trace metal concentrations in plant tissue for biomonitoring and phytoextraction. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 138, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Soil salinity: A global threat to sustainable development. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy, V.; Jagendorf, A.; Zhu, J.K. Understanding and İmproving Salt Tolerance in Plants. Crop Sci. 2005, 45, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdElgawad, H.; Zinta, G.; Hegab, M.M.; Pandey, R.; Asard, H.; Abuelsoud, W. High salinity induces different oxida-tive stress and antioxidant responses in maize seedlings organs. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 276. [Google Scholar]

- El Sayed, H.; El Sayed, A. Influence of salinity stress on growth parameters, photosynthetic activity and cytological studies of Zea mays, L. Plant using hydrogel polymer. Agric. Biol. J. N. Am. 2011, 2, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeel, A.; Sümer, A.; Hanstein, S.; Yan, F.; Schubert, S. In vitro effect of Na+/K+ ratios on the hydrolytic and pumping activity of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase from maize (Zea mays L.) and sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) shoot. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, E.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Ors, S.; Dursun, A. Physiological, morphological and biochemical responses of exogenous hydrogen sulfide in salt-stressed tomato seedlings. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, H.; Hayat, S.; Bajguz, A. Regulation of photosynthesis by brassinosteroids in plants. Acta Physiol. Plant 2018, 40, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, E.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Agar, G.; Ors, S.; Dursun, A.; Kul, R.; Akgül, G. Physiological and Biochemical Changes of Pepper Cultivars Under Combined Salt and Drought Stress. Gesunde Pflanz. 2022, 74, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Chanratana, M.; Kim, K.; Seshadri, S.; Sa, T. Impact of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on pho-tosynthesis, water status, and gas exchange of plants under salt stress–a meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 457. [Google Scholar]

- Alamer, K.H.; Perveen, S.; Khaliq, A.; Zia Ul Haq, M.; Ibrahim, M.U.; Ijaz, B. Mitigation of salinity stress in maize se-edlings by the application of vermicompost and sorghum water extracts. Plants 2022, 11, 2548. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.V. Regulation of chlorophyll biosynthesis and degradation by salt stress in sunflower leaves. Sci. Horti Cult. 2004, 103, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, N.P.; Tripathi, S.B.; Shaw, B.P. Effect of salinity on chlorophyll and proline contents in three aquatic macrophytes. Biol. Plant. 1997, 40, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Rehman, S.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, H.; Rha, E.S. Salinity reduced growth, PS2 photochemistry and chlorophyll content in radish. Sci. Agric. 2007, 64, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambede, J.G.; Netondo, G.W.; Mwai, G.N.; Musyimi, D.M. NaCl salinity affects germination, growth, physio-logy, and biochemistry of bambara groundnut. Br. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 24, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, K.C.; Sharma, B.; Nagpal, S.; Kumar, A.; Tiwari, S.; Nair, R.M. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: Salt stress alleviators to improve crop productivity for sustainable agriculture development. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Akhdar, I.; Elhawat, N.; Shabana, M.M.A.; Aboelsoud, H.M.; Alshaal, T. Physiological and Agronomic Responses of Maize (Zea mays L.) to Compost and PGPR Under Different Salinity Levels. Plants 2025, 14, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aazami, M.A.; Rasouli, F.; Ebrahimzadeh, A. Oxidative damage, antioxidant mechanism and gene expression in to-mato responding to salinity stress under in vitro conditions and application of iron and zinc oxide nanoparticles on callus induction and plant regeneration. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKersie, B.D.; Murnaghan, J.; Jones, K.S.; Bowley, S.R. Iron-superoxide dismutase expression in transgenic alfalfa increases winter survival without a detectable increase in photosynthetic oxidative stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2000, 122, 1427–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicerali, I.N. Effect of Salt Stress on Antioxidant Defense Systems of Sensitive and Resistance Cultivars of Lentil (Lens Culinaris M.). Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Yildirim, E. Biochar mitigates salt stress by regulating nutrient uptake and antioxidant activity, alleviating the oxidative stress and abscisic acid content in cabbage seedlings. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2022, 46, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Molazem, D.; Bashirzadeh, A. Impact of salinity stress on proline reaction, peroxide activity, and antioxidant enzymes in maize (Zea mays L.). Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2015, 24, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes-Benavente, L.; Kernodle, S.P.; Margis-Pinheiro, M.; Scandalios, J.G. Salt-induced antioxidant metabolism de-fenses in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Redox Rep. 2004, 9, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gıll, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, P.; Nelson, L.; Kloepper, J.W. Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant Soil 2014, 383, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, A.H.; Maung, T.T.; Kim, C.K. The ACC deaminase-producing plant growth-promoting bacteria: Influences of bacterial strains and ACC deaminase activities in plant tolerance to abiotic stress. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 1992–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.D.G.C.; Medeiros, A.O.; Converti, A.; Almeida, F.C.G.; Sarubbo, L.A. Biosurfactants: Promising biomolecules for agricultural applications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mıller, G.; SuzukI, N.; Cıftcı-yılmaz, S.; Mıttler, R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during dro-ught and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 453. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, P.; Prasad, M.N.V. (Eds.) Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants: Metabolism, Productivity and Sustainability; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Li, J.; Chong, K.; Harter, K.; Lee, Y.; Leung, J.; Martinoia, E.; Matsuoka, M.; Offringa, R.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Toward a molecular understanding of plant hormone actions. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, P.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wan, H.; Liu, C.; Ni, Z. The soybean F-box protein GmFBX176 regulates ABA-mediated responses to drought and salt stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 176, 104056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Chong, P.; Zhao, M. Effect of salt stress on the photosynthetic characteristics and endogenous hormones, and: A comprehensive evaluation of salt tolerance in Reaumuria soongorica seedlings. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, 2031782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, H.; Cho, Y.G. Plant hormones in salt stress tolerance. J. Plant Biol. 2015, 58, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Choudhary, K.K. Salt stress resilience in plants mediated through osmolyte accumulation and its crosstalk mechanism with phytohormones. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1006617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Ekinci, M.; Ors, S.; Turan, M.; Yildiz, S. Effects of individual and combined effects of salinity and drought on physiological, nutritional and biochemical properties of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata). Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, Z. Bazı Abiyotik Streslerin Prolinle Desteklenen Turuçgil Anacı Çöğürleri Üzerine Morfolojik, Fizyolojik ve Biyokimyasal Etkileri. Master’s Thesis, Akdeniz Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Bahçe Bitkileri Anabilim Dalı, Antalya, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, A.R.; Roy, C.; Sengupta, D.N. Transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing the heterolo-gous lea gene Rab16A from rice during high salt and water deficit display enhanced tolerance to salinity stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2007, 26, 1839–1859. [Google Scholar]

- Binzel, M.L.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Rhodes, D.; Handa, S.; Handa, A.V.; Bressan, R.A. Solute accumulation in tobacco cells adapted to NaCl. Plant Physiol. 1987, 84, 1408–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Sarkadi, L.; Kocsy, G.; Varhegyi, A.; Galiba, G.; de Ronde, J.A. Genetic manipulation of proline accumulation in-fluences the concentrations of other amino acids in soybean subjected to simultaneous drought and heat stress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 7512–7517. [Google Scholar]

- Slama, I.; Abdelly, C.; Bouchereau, A.; Flowers, T.; Savoure, A. Diversity, distribution and roles of osmoprotective compounds accumulated in halophytes under abiotic stress. Ann. Bot. 2015, 115, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelin, H.; Devi, T.S.; Gupta, S.; Kapoor, R. Mitigation of salinity stress in plants by arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: Current understanding and new challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 450967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Fromm, J.; Schmidhalter, U. Effect of salinity on tissue architecture in expanding wheat leaves. Planta 2005, 220, 838–848. [Google Scholar]

- Shabala, S.; Cuin, T.A. Potassium transport and plant salt tolerance. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 133, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demidchik, V.; Maathuis, F.J. Physiological roles of nonselective cation channels in plants: From salt stress to signalling and development. New Phytol. 2007, 175, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E.; Møller, I.M.; Murphy, A. Plant physiology and development. In Fundamentos de Fisiologia Vegetal-6; Artmed Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Parihar, P.; Singh, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Effect of salinity stress on plants and its tolerance strategies: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 4056–4075. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, A.; Prasad, P.; Das, S.N.; Kalam, S.; Sayyed, R.; Reddy, M.; El Enshasy, H. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) as-green bioinoculants: Recent developments, constraints, and prospects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofano, F.; El-Nakhel, C.; Colla, G.; Cardarelli, M.; Pii, Y.; Lucini, L.; Rouphael, Y. Modulation of mor-pho-physiological and metabolic profiles of lettuce subjected to salt stress and treated with two vegetal-derived bi-ostimulants. Plants 2023, 12, 709. [Google Scholar]

- Giannelli, G.; Potestio, S.; Visioli, G. The Contribution of PGPR in Salt Stress Tolerance in Crops: Unravelling the Molecular Mechanisms of Cross-Talk between Plant and Bacteria. Plants 2023, 12, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Habib, S.; Ahmed, A.; Haque, M.F.U.; Ejaz, R. Efficacious use of potential biosurfactant producing plant growth promoting rhizobacteria to combat petrol toxicity in Zea mays L. plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 53725–53740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lephatsi, M.M.; Meyer, V.; Piater, L.A.; Dubery, I.A.; Tugizimana, F. Plant Responses to Abiotic Stresses and Rhizobacterial Biostimulants: Metabolomics and Epigenetics Perspectives. Metabolites 2021, 11, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, M.; Yildirim, E.; Ekinci, M.; Argin, S. Effect of biostimulants on yield and quality of cherry tomatoes grown in fertile and stressed soils. HortScience 2021, 56, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakkammal, K.; Maharajan, T.; Ceasar, S.A.; Ramesh, M. Biostimulants and their role in improving plant growth under drought and salinity. Cereal Res. Commun. 2023, 51, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Franzoni, G.; Cocetta, G.; Prinsi, B.; Ferrante, A.; Espen, L. Biostimulants on crops: Their impact under abiotic stress conditions. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, D.P.; Cameotra, S.S. Biosurfactants in agriculture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.; Rasheed, Y.; Asif, K.; Ashraf, H.; Maqsood, M.F.; Shahbaz, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Sardar, R.; Haider, F.U. Plant Biostimulants: Mecha-nisms and Applications for Enhancing Plant Resilience to Abiotic Stresses. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 6641–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, P.; Ali, N.; Saini, S.; Pati, P.K.; Pati, A.M. Physiological and molecular insight of microbial biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1041413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, C.; Benito, P.; Porcel, R.; Bellón, J.; González-Guzmán, M.; Arbona, V.; Yenush, L.; Mulet, J.M. Field evalu-ation and characterization of a novel biostimulant for broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) cultivation under drought and salt stress which increases antioxidant, glucosinolate and phytohormone content. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113584. [Google Scholar]

- Desoky, E.-S.M.; Merwad, A.-R.M.; Rady, M.M. Natural biostimulants improve saline soil characteristics and salt stressed-sorghum performance. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant Anal. 2018, 49, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirk, W.A.; Tarkowská, D.; Turečová, V.; Strnad, M.; Van Staden, J. Abscisic acid, gibberellins and brassinosteroids in Kelpak®, a commercial seaweed extract made from Ecklonia maxima. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113584, Erratum in J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-013-0062-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, A.O.; Stirk, W.A.; Kulkarni, M.G.; Tarkowská, D.; Turečková, V.; Gruz, J.; Šubrtová, M.; Pěnčík, A.; Novák, O.; Dolezal, K.; et al. Evidence of phytohormones and phenolic acids variability in gar-den-waste-derived vermicompost leachate, a well-known plant growth stimulant. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 75, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amist, N.; Singh, N.B. Responses of enzymes involved in proline biosynthesis and degradation in wheat seedlings under stress. Allelopath. J. 2017, 42, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Alam, M.M.; Rahman, A.; Suzuki, T.; Fujita, M. Polyamine and nitric oxide crosstalk: An-tagonistic effects on cadmium toxicity in mung bean plants through upregulating the metal detoxification, antioxidant defense, and methylglyoxal detoxification systems. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 126, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanasi, T.; Karavidas, I.; Spyrou, G.P.; Giannothanasis, E.; Aliferis, K.A.; Saitanis, C.; Fotopoulos, V.; Sabatino, L.; Savvas, D.; Ntatsi, G. Plant Biostimu-lants Enhance Tomato Resilience to Salinity Stress: Insights from Two Greek Landraces. Plants 2024, 13, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İkiz, B.; Dasgan, H.Y.; Balik, S.; Kusvuran, S.; Gruda, N.S. The use of biostimulants as a key to sustainable hydropo-nic lettuce farming under saline water stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 808. [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew, L. Humic substances in biological agriculture. RevAcres USA 2004, 34, 414–423. [Google Scholar]

- Canellas, L.P.; Olivares, F.L.; Aguiar, N.O.; Jones, D.L.; Nebbioso, A.; Mazzei, P.; Piccolo, A. 2015 Humic and fulvic acids as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hort. 2015, 196, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Eras-Muñoz, E.; Farré, A.; Sánchez, A.; Font, X.; Gea, T. Microbial biosurfactants: A review of recent environmental applications. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 12365–12391. [Google Scholar]

| Product | Component Category | Components | Quantitative Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biostimulant (B) | Microorganisms | Paenibacillus polymyxa, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus licheniformis, Azotobacter chroococcum, Azospirillum brasilense | 1 × 109 cfu/mL (total viable cell concentration) |

| Enzymes | Protease, | Protease 300 U/g, | |

| Xylanase, | Xylanase 1700 U/g, | ||

| α-amylase, | α-amylase 1750 U/g, | ||

| Cellulase + Hemicellulase, | Cellulase + Hemicellulase 200 U/g, | ||

| Phytase | Phytase 500 U/g | ||

| Organic Acids | Fulvic acid | 100 ppm | |

| Hormones (microbial origin) | Auxins (IAA), Cytokinins, Gibberellic acid | Produced in situ by microbial metabolism | |

| Enriched-Surfactant (E-S) | Surfactant base | Trisiloxane alkoxylate (trioksisilan) | 0.2% (v/v) |

| Enzymes | Protease, | Protease 300 U/g, | |

| Lipase, | Lipase 150 U/g, | ||

| Cellulase + Hemicellulase | Cellulase + Hemicellulase 200 U/g | ||

| Organic Acids | Fulvic acid | 100 ppm | |

| Microorganisms | Same bacterial consortium as B | 1 × 109 cfu/mL |

| Variable | Treatment (df = 11) | Error (df = 24) |

|---|---|---|

| PFW (g/plant) | 425.299 ** | 0.283 |

| PDW (g/plant) | 4.400 ** | 0.000 |

| RFW (g/plant) | 168.625 ** | 0.063 |

| RDW (g/plant) | 1.751 ** | 0.001 |

| LA (cm2/plant) | 152.102 ** | 1.648 |

| Chl a (mg/g) | 4.708 ** | 0.002 |

| Chl b (mg/g) | 1.492 ** | 0.004 |

| Total Chl (mg/g) | 10.261 ** | 0.010 |

| H2O2 (mmol/kg) | 63,344.490 ** | 84.548 |

| MDA (mmol/kg) | 42,765.357 ** | 19.940 |

| SOD (eu/g leaf) | 5,920,878.870 ** | 17,103.526 |

| CAT (eu/g leaf) | 669,171.923 ** | 1157.594 |

| POD (eu/g leaf) | 199,872,189.966 ** | 106,248.279 |

| IAA (ng/mg tissue) | 1223.810 ** | 2.175 |

| GA (ng/gDW) | 81,917,286.817 ** | 70,215.063 |

| ABA (ng/gDW) | 4,134,422.278 ** | 4949.818 |

| Proline (%) | 0.769 ** | 0.001 |

| Sucrose (%) | 4.910 ** | 0.043 |

| L-K (%) | 2.266 ** | 0.003 |

| L-Ca (%) | 1.485 ** | 0.004 |

| L-Na (%) | 74,688.227 ** | 57.944 ** |

| L-Cl (mg/g) | 87,044.816 ** | 315.093 |

| R-K (%) | 0.684 ** | 0.001 |

| R-Ca (%) | 0.275 ** | 0.000 |

| R-Na (mg/g) | 153,174.538 ** | 174.727 |

| R-Cl (mg/g) | 6464.997 ** | 113.090 |

| Variable | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFW (g/plant) | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| PDW (g/plant) | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.01 |

| RFW (g/plant) | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.07 | −0.05 |

| RDW (g/plant) | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.06 | −0.01 |

| LA (cm2/plant) | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.03 | −0.19 |

| Chl a (mg/g) | 0.17 | −0.22 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| Chl b (mg/g) | 0.12 | −0.31 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| Total Chl (mg/g) | 0.17 | −0.22 | 0.32 | 0.29 |

| H2O2 (mmol/kg) | −0.23 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| MDA (mmol/kg) | −0.21 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

| SOD (eu/g leaf) | −0.18 | −0.08 | 0.35 | −0.14 |

| CAT (eu/g leaf) | −0.08 | −0.53 | 0.12 | −0.07 |

| POD (eu/g leaf) | −0.09 | −0.21 | 0.23 | −0.53 |

| IAA (ng/mg tissue) | 0.20 | −0.03 | 0.28 | 0.19 |

| GA (ng/gDW) | −0.23 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| ABA (ng/gDW) | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| Proline (%) | −0.20 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

| Sucrose (%) | 0.01 | −0.20 | −0.28 | 0.44 |

| L-K (%) | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.02 |

| L-Ca (%) | 0.22 | −0.13 | 0.14 | −0.07 |

| L-Na (%) | −0.23 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| L-Cl (mg/g) | −0.22 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| R-K (%) | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| R-Ca (%) | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.29 | −0.26 |

| R-Na (mg/g) | −0.21 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| R-Cl (mg/g) | −0.20 | 0.05 | 0.35 | −0.03 |

| Eigenvalue | 17.35 | 2.74 | 1.87 | 1.64 |

| Percentage of Variance | 66.73% | 10.52% | 7.19% | 6.29% |

| Cumulative | 66.73% | 77.25% | 84.44% | 90.73% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gul, Z.; Ekinci, M.; Akca, M.; Turan, M.; Yigider, E.; Aydin, M.; Eken Türer, N.I.; Yildirim, E. Enhanced Salt Stress Tolerance in Maize Using Biostimulant and Biosurfactant Applications. Agronomy 2026, 16, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010100

Gul Z, Ekinci M, Akca M, Turan M, Yigider E, Aydin M, Eken Türer NI, Yildirim E. Enhanced Salt Stress Tolerance in Maize Using Biostimulant and Biosurfactant Applications. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleGul, Zeynep, Melek Ekinci, Melike Akca, Metin Turan, Esma Yigider, Murat Aydin, Nazlı Ilke Eken Türer, and Ertan Yildirim. 2026. "Enhanced Salt Stress Tolerance in Maize Using Biostimulant and Biosurfactant Applications" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010100

APA StyleGul, Z., Ekinci, M., Akca, M., Turan, M., Yigider, E., Aydin, M., Eken Türer, N. I., & Yildirim, E. (2026). Enhanced Salt Stress Tolerance in Maize Using Biostimulant and Biosurfactant Applications. Agronomy, 16(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010100